Abstract

Oncologists should plan for a future beyond full-time oncology, but there is little practical guidance for a successful transition into retirement. This paper provides strategies for various aspects of retirement planning and transitioning. More prospective information is needed.

Paul McCartney was 16 when he first penned the song, “When I'm Sixty-Four.” Did he realize back then that he would still be working well into his 70s? Has he had thoughts on transitioning into retirement? Like the music industry, the practice of oncology demands a lot of time in close contact with anxiety, distress, and premature death. Despite these stresses, most oncologists manage to achieve a balanced life by maintaining an interest in research, teaching, and the well-being of patients. Nevertheless, we should all plan for a future beyond full-time oncology. Although we may have informal “corridor discussions” about retirement, usually with older colleagues, there is little practical guidance for a successful transition into retirement.

When Do Oncologists Tend to Retire?

One question to tackle when planning retirement is, “When do most of my colleagues tend to retire?” This question enables one to broadly estimate the likely duration of one's working life. It is difficult to obtain up-to-date information about when oncologists retire. Anyone who regularly attends cancer conferences cannot help but notice an aging of the workforce. Whether or not this phenomenon is real or simply self-consciousness about our own age is not clear. Indeed, as we watch “Dr. Vogel, New York” take the microphone on the floor at San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium or at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) meeting, he seems to blend increasingly into the sea of gray around him. This observation is likely confirmed by the results of an ASCO survey of oncologists in the U.S. that showed around 54% of practicing medical oncologists will be aged 65 or older by 2020 [1]. This survey also showed that the expected retirement age of respondents was 64.3 years, and most of those who were still working after age 64 planned to retire within the following 3–4 years [1]. In Canada, the average age of retirement for medical oncologists is 65 years, although many did not call themselves “completely retired” until their mid-70s [2]. A high proportion of physicians go through a semiretirement stage that extends anywhere from the early 60s to the early 70s.

Another way to pose the question about the timing of retirement is, “How long do doctors live?” There can be few who plan to spend their last day of life at the office or the clinic. To paraphrase, “No man ever said on his deathbed, I wish I had spent more time in the office.” Although we were unable to obtain data for average age of death for oncologists, we know that that the average age of doctors dying in the past 20 years is 77 years for all specialties; this average age is likely to increase in the future [2, 3].

What Do You Need in Place for Retirement?

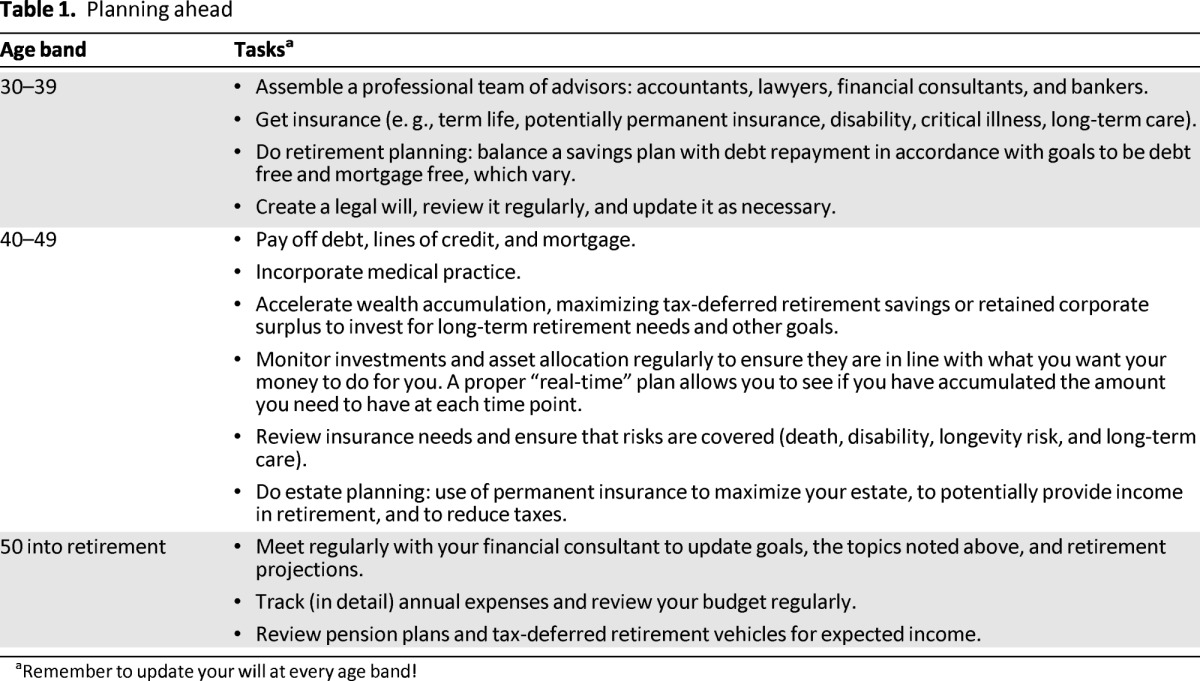

Proper retirement planning should start early and involves much thinking and decision making throughout one's career (Table 1). The needs of the newly qualified 35-year-old oncologist with a young family, who is buying a mortgaged home, saving for children's education costs, and repaying student debt, are different from those of the 60-year-old with no mortgage and the “sudden” realization that he or she needs to plan for retirement. Oncologists (and physicians in general) should start saving while they are young if they expect to retire at a reasonable age and with a good standard of living. The process starts with a detailed understanding of one's current financial situation and goals in the short, medium, and long term. To maintain the lifestyle to which one has become accustomed, a common formula is that one should save enough to draw 70% of preretirement annual earnings. Certainly, part of this 30% reduction can be made up by having no debt or dependents, no work-related expenses, more time to seek out bargains, and avoiding “foolish” spending by practicing general thrift. One should then try to determine a precise required retirement income and learn how to manage choices and how to understand the risks associated with one's various income sources. One can then create a road map for modeling and reviewing final retirement plans.

Table 1.

Planning ahead

aRemember to update your will at every age band!

Seeking advice and guidance from an experienced financial advisor is a good start for developing a personalized and comprehensive financial plan. Choose an advisor who will track your progress on a regular basis. These experts can manage investments and pension plans and suggest appropriate life insurance coverage. Although salaried oncologists may contribute to a formal pension plan, private practitioners might not. In the absence of a plan, it is important to save and build wealth by implementing regular savings discipline using a combination of savings accounts. For those who can incorporate, there could be other strategies, all of which may provide for tax-efficient wealth accumulation for retirement. Implementing and maintaining an up-to-date and legal will, powers of attorney for health and property, and clear plans for children and grandchildren as well as discussion of charitable donations are also important. One should also create an advanced directive—after all, we all expect our patients to do this—and review life insurance annually. As retirement approaches, one will also need to make plans for winding up one's practice.

Like all phases of a medical career, retirement requires a degree of planning and forethought, often best started many years in advance. The physician whose only source of satisfaction is the workplace is much more likely to suffer acute distress—psychological, intellectual, and emotional—at the time of retirement [4]. The physician who has been involved in family, hobbies, community life, and other activities is likely to transition more easily, replacing the satisfactions of a medical career with those found elsewhere [4]. Creating balance in life prior to retirement can be beneficial.

How Do You Handle Risk?

Retirement planning has many uncertainties for all physicians. There are risks to achieving a secure lifetime income. Longevity poses risk associated with outliving one's income-producing assets, that is, you have to plan for living longer than you expect. Inflation increases future costs of goods and services and erodes the value of assets set aside to meet those costs. To mitigate this risk, include investments with the potential to outpace inflation in your long-term portfolio and investment plan. With global “quantitative easing,” pension plans are under stress and annual cost-of-living adjustments likely will not keep pace with inflation. Asset allocation depends on individual circumstances to get a precise mix but should be based on one's risk tolerance and proximity to retirement. Excess withdrawal poses risk depending on one's age and capital accumulated. Withdrawal rates over 4% may increase the risk of running down capital savings. Prudent withdrawal rates will extend the life of a portfolio.

Health care expenses in retirement are hard to determine, but they must be included in retirement planning. Extra savings and insurance may give one more choice in the future as well as peace of mind. Everyone should have a good disability plan in place with a sliding scale pay-out range depending on age, from 70% of one's current income in one's 30s to 30% or less in one's 60s (depending on current responsibilities). Also consider long-term care insurance (much like a disability policy but not based on income), which may need to be used anytime and may prevent a depletion of retirement assets by providing a monthly benefit to cover costs associated with a debilitating illness.

Is Continuing to Work Beyond Age 65 Necessarily a Bad Thing?

No! Experience is one of the great things that comes with age! We live in challenging times of cutbacks and departmental “transformation” and “improvement.” Many of these issues have similar causes and build-ups and have been dealt with before in previous years (sometimes several times) and can be looked at through the eyes of experience. With oncologists working on average 53.7 hours a week [1], however, aging oncologists have to realize they must fully pull their weight if they expect to receive the same full-time income as younger colleagues.

Workforce studies have demonstrated that the demand for medical oncology services, related to increases in both incident and prevalent cases, is expected to outgrow the capacity to provide those services as the physician population ages [1]. High priority should be given to workforce planning and resource management [5, 6]. A number of changes to our current model of care would help reduce this gap between demand and capacity, including broader employment of nurse practitioners and advance practice nurses as well as appropriate transitioning of patients back to their primary care providers [6, 7].

Another component of the plan needs to include strategies that promote a gradual transition into retirement. De-escalating clinical responsibilities over a period of time would allow medical oncologists to extend their careers and provide the benefit of their experience to a system that will find specialist physician resources in short supply. In Ontario, Canada, less than 10% of medical oncologists are currently working part time, and although an ASCO survey similarly showed that 8% of oncologists were working part time in the U.S., many more were interested in this option [1]. The transition model would need to be properly planned and supported, and issues related to remuneration, on-call duties, and other fundamental practical details would need to be explicitly addressed. Regular on-call duties after age 65 would be undesirable, although we can find no evidence that medico-legal risk increases as we age.

One word of caution in this discussion relates to burnout. Burnout is more common as we get older and is associated with earlier retirement [8, 9]. Given the risk of burnout in the practice of medicine (e.g., sleep deprivation, excessive work and patient demands, potential litigation, witnessing trauma and human suffering), regular review of one's work-life balance is essential [3, 8]. Continuing to use one's basic skills and experience but developing new skills and knowledge in a different disease site or discipline or perhaps moving into medical education, politics, or administration can help maintain a healthy work-life balance.

Transition

Although the idea of a seamless transition into retirement may seem straightforward, plenty of evidence shows this might not always be the case [10]. The transitioning physician should actively look for alternatives and take advantage of opportunities that arise. A good avocation (e.g., painting, woodwork, foreign language, writing) can be expanded and can contribute to a rewarding transition. Everyone seems to want to travel, and we suspect that will not be enough in itself to provide a satisfying transition. An avocation has to be worked at well before retiring. It is also important (if you love medicine) to continue contributing. This may mean moving into work that others find less attractive (e.g., poorly paid overseas work, pharmaceutical industry, insurance companies, locums in small cities, developing a clinic in medically underappreciated and underfunded areas such as nutrition, pain management, or home visiting). Important but less glamorous committee work, such as chairing the library committee or volunteering for jobs that involve a fair amount of extra work like the research committee, will earn the appreciation of younger colleagues.

There are many pathways to retirement. Some like to retire cold turkey. Others want to continue contributing and indeed can and do, sometimes doing more (much more), especially in academic activities and mentoring, than younger members. That said, colleagues recognize very quickly if you are not pulling your weight. In this situation, seniority should not be viewed as something to hide behind. At each year over age 65, a full and honest review is required, at the same depth and level that applies to all.

What About Your Colleagues?

Retirement affects not only the retiree but also the practice from which one is retiring. Many strategies are being introduced by individual practices to ease the transition resulting from the retirement of an active practitioner. The most important is likely to be planning for retirement in an open and honest fashion. A written plan and guidelines are fundamental [11]. Although part-time work may be attractive, many practices are unable to accommodate it [1]. Reducing hours is one way to ease the transition into retirement, as is shifting the focus of workload from patient care to perhaps a more academic focus on research or mentoring. Other practices include scaling back on-call hours or stopping the intake of new patients into a soon-to-be-retiring physician's practice [12]. The retiree can be a mentor to incoming practice members or can job share. These changes lead to changes in remuneration and should be agreed upon and documented in advance.

De-escalating one physician will often lead to a higher workload for other practice members, if a replacement is not being incorporated. Again, a written plan can ensure a smooth transition. Such strategies also require the cooperation of many, including partners, patients, hospitals, and professional liability insurers. Practices that report a crossover period of “shared care” between the outgoing practitioner and the incoming practitioner report high patient satisfaction [11]. There may be other unanticipated downsides to transition. Some studies suggest that patient outcomes decrease when patients change doctors [13], but perhaps this too can be offset by the ongoing assistance of the retiring physician [13, 14].

Is There Life After Retirement?

Retirement is not only about financial losses; with retiring comes the loss of many other aspects of self. Laliberte observed, “Medicine is an all-encompassing profession, so it is normal to feel like you've lost a part of yourself when it comes to an end” [14]. For many physicians, a large part of self-identity is tied to being a doctor. This loss is felt not only personally but also by family, colleagues, and patients. Retirement surveys have shown consistently that the first year of retirement is the most stressful, and these stressors are predominantly nonfinancial. Up to 27% of retired physicians exhibit some signs of depression [15]; however, there are also documented benefits. Health may actually improve with more time to devote to personal well-being and exercise, spousal relationships more often improve than deteriorate, and a third of physicians agree that retirement years are the best of their lives [15].

Conclusion

Retirement planning and transition is important in order to enjoy the remaining years of one's life. It is also important to free up resources to give opportunities to younger generations. In any department of oncology, it is an advantage to have a range of ages and experience. While researching this paper, it became increasingly evident that there is a paucity of information to support effective transition into retirement, and more prospective information is needed. Potential data would be extremely useful, possibly in the form of more oncologist surveys evaluating how retirement and transitioning of the oncology workforce fits in with overall oncology manpower requirements, given the increasing clinical workload, cancer incidence, and case complexity. This issue is important because the median age of oncologists will change, but the demographic make-up of the field is also changing. Currently 24% of the oncology workforce are women and 45% of oncologists are under age 35 [1].

We hope this paper will remind people that they, like their patients, will not live forever. With planning and more than a little luck, let us hope we will all be able to watch Paul McCartney work well into his 80s. Perhaps he might find this paper useful?

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bill Evans (retiring in 2013) and Brent Vandermeer (Fraser Vandermeer Asset Management) for their insights into this commentary.

A.H.P. is dreaming of a long and happy retirement on his boat but can't quite afford it yet. M.J.C. would simply like to believe his children will one day leave home.

Disclosures

Ian Gunstone: MD Management, Ltd. (E). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, et al. Forecasting the supply of and demand for oncologists: A report to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) from the AAMC Center for Workforce Studies Center for Workforce Studies. 2007. Mar, [Accessed September 1, 2013]. Available at http://www.asco.org/sites/default/files/oncology_workforce_report_final.pdf.

- 2.CMA Centre for Physician Health and Well-Being. The non-financial aspects of physician retirement: Environmental scan & literature review. 2004. Aug, [Accessed September 1, 2013]. Available at http://www.cma.ca/multimedia/staticContent/CMA/Content_Images/Inside_cma/Physician-Health/English/pdf/Retirement-lit-summary.pdf.

- 3.Appleby J. How long can we expect to live? BMJ. 2013;346:f331. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rice B. Retire early? These docs did and came back. Med Economics. 2003;80:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fasola G, Aprile G, Aita M. A model to estimate human resource needs for the treatment of outpatients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:13–17. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cancer Care Ontario. Regional systemic treatment program: Provincial plan. 2009. Sep, [Accessed September 1, 2013]. Available at https://www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=58067.

- 7.Towle EL, Barr TR, Hanley A, et al. Results of the ASCO study of collaborative practice arrangements. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:278–282. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spickard A, Jr., Gabbe SG, Christensen JF. Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. JAMA. 2002;288:1447–1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leiter M, Frank E, Matheson T. Demands, values, and burnout: Relevance for physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:1224–1225. 1225.e1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drife JO. In and out of hospital. Retirement: The four year itch. BMJ. 2013;346:f1318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ensure the future of your practice through early succession planning. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5:136–138. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0932505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Managing practices. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:119–120. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker L. Your career guide. Winding down, bowing out. Leaving practice but not the profession. Med Econ. 2001;78:96, 99–101, 105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laliberte J. The perfect retirement plan: Emotional preparedness key to later life happiness. Nat Rev Med. 2007. [Accessed September 1, 2013]. p. 4. Available at http://www.nationalreviewofmedicine.com/issue/special_sections/2007/4_physician_wellness06_1.html.

- 15.Lees E, Liss SE, Cohen IM, et al. Emotional impact of retirement on physicians. Tex Med. 2001;97:66–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]