We thank the editor1 of the Critical Topics Forum and our esteemed colleagues2–5 for appraising our work. The three papers under discussion6–8 focus on the peptide melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) and the neurons in the lateral hypothalamus that contain it. The MCH neurons are listed as regulating REM sleep but not as a sleep-promoting group in current network models of sleep-wake generation.9 Indeed, only one sleep group—the ventral lateral preoptic (VLPO) and the median preoptic (MnPO)—is listed in current models. Considerable data support the status of the VLPO/MnPO in sleep-wake models,10,11 but as these neurons have never been selectively stimulated their role in sleep is still unproven. On the other hand, our study used optogenetics to cement the status of MCH neurons in sleep circuit models.7

Jego et al.8 also used optogenetics to stimulate the MCH neurons. They activated the MCH neurons during REM sleep, which lengthened the bout, but silencing these neurons did not abort the bout. This was also noted by Luppi et al.5 Moreover, they only stimulated during sleep and not waking. As such, they did not identify the MCH neurons as belonging to network models of sleep-wake regulation, which is what we discovered. By narrowly focusing on REM sleep they missed the translational potential of MCH neuron stimulation—to alleviate insomnia.

They created a new mouse model, Tg(Pmch-Cre), to target the entire MCH neuron population in the lateral hypothalamus and zona incerta. Unfortunately, 16.4% of the MCH neurons did not express the reporter gene. In fact, MCH neurons in the zona incerta did not contain the reporter or the light-sensitive opsin, ChETA (Figs. 1B and 1C8), which was also noted by Luppi et al.5 Moreover, 10.35% of non-MCH neurons contained ChETA (compare Figure 1B versus Figure 1C in their paper). Did any of the wake-active hypocretin/orexin neurons contain ChETA in their study? Thus, their mouse line does not hold an advantage over our approach as suggested by McGinty and Alam.4

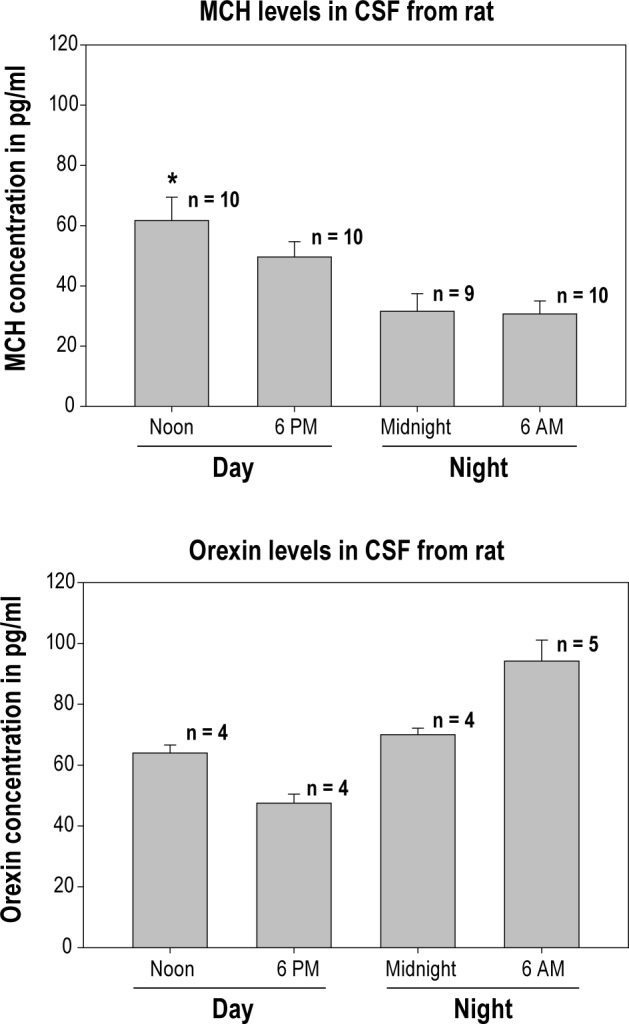

Figure 1.

CSF levels of MCH and orexin-A in the cisterna magna of Long-Evans rats at different circadian time points. MCH and orexin-A were assessed using ELISA according to manufacturer's instructions. For MCH the numbers atop each bar represent individual rats and demonstrates significantly more MCH at noon (first 6 h of lights-on sleep phase) compared to midnight or at the end of the dark cycle (6AM) (P < 0.05). Orexin-A levels were assessed by pooling CSF samples from what was left after completing the MCH assay. Note that there is more circulating orexin-1 compared to MCH, perhaps because the proportion of waking is more relative to sleep.

We took a more cost-effective approach that can be applied broadly across all animals that have rest-activity cycles. We used a full-length proven MCH promoter12 to create rAAV-MCHChR2(H134R)-EYFP to specifically target the MCH neurons in all vertebrates. With it we identified the largest single phenotype of neurons implicated in both NREM and REM sleep. Our vector can be inserted into zebra fishes or day-active rodents such as the Nile rats. We suggest that there should be an MCH analogue that induces behavioral sleep (rest) in nematodes and flies.

We disagree with the conclusion of Jego et al.8 that MCH neurons increase length of REM sleep bouts by inhibiting the tuberomammillary nucleus histamine neurons. The primary problem with their conclusion is that the histamine neurons are already silent during REM sleep13 and, therefore, not releasing histamine at target sites. How does adding more inhibitory MCH/GABA onto these already silent neurons make them release less histamine? We suggest that the effects were obtained by light stimulating some of the MCH somata, which at this level are in close proximity to the histamine neurons. Inhibiting the dorsal raphe serotonin neurons should have lengthened REM sleep bouts based on established literature,14 but it did not, which reinforces our point that in the tuberomammillary nucleus MCH somata were also stimulated.

As for the medial septum it generates theta and not REM sleep. Theta can be blocked in the medial septum without affecting REM sleep.15 As such, what they found upon stimulating the medial septum was an increase in theta and not an increase in REM sleep. We emphasize that hippocampal theta is also present during waking when MCH neurons are silent. How can MCH neurons stabilize theta during both waking and REM sleep when they are silent in one and active in the other?

The reviewers wondered why only high stimulation rates evoked behavior in both the pre-clinical studies when the MCH neurons fire at 1 Hz during REM sleep (Figure 1 in Jones and Hassani3). We used 0, 5, 10, and 30 Hz in a repeated measures design that recorded sleep over a 24-h period and found that 10 Hz was most effective. We chose to stimulate at night when the mice are awake to better identify the potency of the effect. Jego et al.8 stimulated acutely only during the day cycle when the animals were already asleep, and all the arousal neurons silent. They briefly activated the MCH neurons at 20 Hz during REM sleep and prolonged the REM sleep bout. Stimulation during NREM did not prolong the bout but increased probability of transitions to REM sleep. They did not report the data about silencing during NREM sleep and whether it decreased the probability of REM sleep, or whether it decreased the NREM bout. Thus, in our study, 10 and 30 Hz stimulated both NREM and REM sleep in awake mice, whereas in their study 20 Hz was better for REM sleep in sleeping animals.

McGinty and Alam4 noted that neither optogenetic study identified how many MCH neurons were activated by light. We agree, but this question cannot be answered, even with c-FOS because of second and third order activation. It is especially difficult when the neuronal population is as dispersed as the MCH neurons. We found that 53.4% (+ 6.4) of the MCH neurons dorsal to the fornix, especially in the zona incerta, and 19.6% (+ 1.8) in the ventral and lateral hypothalamus contained channelrhodopsin, ChR2+EYFP. Therefore, in our study at a maximum all of the MCH neurons (53.4% in zona incerta and 19.6% in the lateral group) were activated, or at a minimum only one MCH neuron was activated by light. Clearly, this emphasizes the potency of MCH neurons to induce both NREM and REM sleep. Jego et al.8 also activated a subset of MCH neurons since their transgenic mice lacked Cre in zona incerta MCH neurons. We note that in both mice studies the recombinant adenoassociated virus was microinjected into the MCH neuron area and the degree of infection of MCH neurons depends on titer strength, volume, and diffusion.

McGinty and Alam4 suggested that heat from the optical lights could have affected sleep. However, this was appropriately controlled in both mice studies. We used an LED (power at the tip of the probe was 1 mW) versus a laser (tip power 30-40 mW) in the Jego et al.8 study. We purposely decreased the power to better evaluate the effects of chronic optical stimulation over the 24-h diurnal rhythm of the sleep-wake cycle.

If MCH neurons promote sleep are MCH levels high in sleep? In the third study in this discussion, Blouin et al.6 found that in human amgydala MCH levels increased with sleep onset and were high relative to levels of hypocretin-1(orexin-A). Our preliminary data (Figure 1) in rats show that CSF levels of the two peptides oscillate in a reciprocal manner consistent with the diurnal rhythm of sleep-wake. These data make it unlikely that MCH neurons selectively regulate REM sleep as suggested by Jego et al.8

MCH has been implicated in feeding but optical activation of MCH neurons did not induce eating in either of the mice studies. Indeed, we found that mice slept rather than eat at a circadian time point when they normally should be eating. In our study, the mice had satiated their sleep need and undoubtedly were hungry. Yet, they slept in response to MCH neuron stimulation. This indicates that sleep trumps hunger. It is well known that people and animals will sleep in spite of hunger.

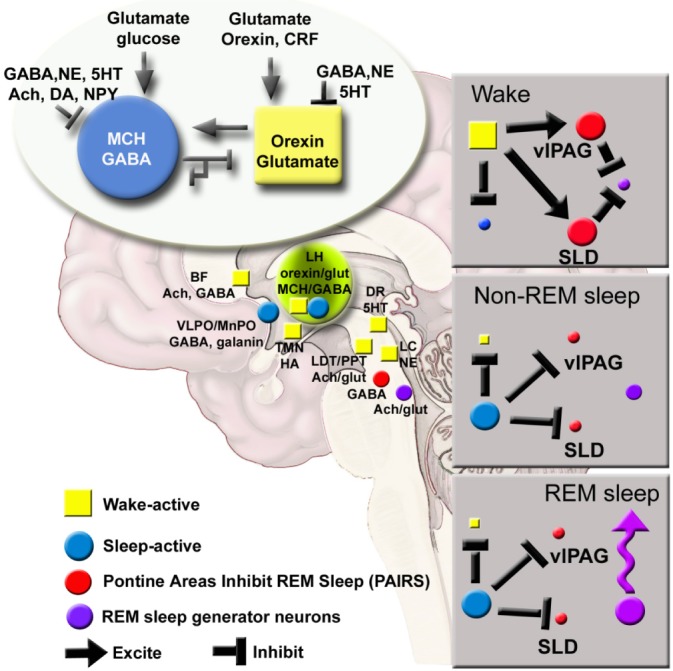

Theoretical framework: We hypothesize that the MCH neurons are the primary initiators of sleep based on our discovery that activating MCH neurons can generate sleep in spite of a strong waking drive (Figure 2). The other sleep-active group is located in the preoptic area.10,11 We hypothesize that sleep begins with activity of the sleep-active neurons (preoptic and MCH). The MCH neurons inhibit the local orexin neurons,16 which decreases orexin's drive of downstream arousal neurons. The preoptic sleep-active neurons also inhibit the arousal neurons.11,17 The increasing strength of activity of the sleep-active MCH-preoptic neurons inhibits GABA neurons in the pons,18 which then allows REM sleep-active neurons to fire and REM sleep ensues. Sleep ends because the MCH neurons are self-inhibiting (both MCH and GABA are inhibitory).12,19 Indeed, our study found that with MCH neuron stimulation length of wake bouts was cut in half but the length of NREM or REMS bouts was unchanged. The wake state ends because the hypocretin/orexin neurons activate the MCH neurons.12,20 Both the MCH and the hypocretin/orexin neurons are located in a region sensing energy metabolism. A rise in glucose activates MCH neurons, which may explain post-prandial sleep,21 as also noted by Luppi.5 The strength of the MCH neurons versus the hypocretin/orexin neurons determines sleep and wake. Combination of MCH agonists and dual orexin receptor antagonists could be useful in insomnia.

Figure 2.

MCH-orexin local antagonism model of sleep-wake regulation. In the new model MCH/GABA neurons are represented along with the preoptic neurons. Strength of MCH versus orexin determines sleep versus wake. REMS occurs when both preoptic and MCH neurons inhibit pontine GABA neurons in the VLPAG/SLD which then allows REM sleep-active neurons to fire. Thus, in our model activation of MCH neurons should promote both NREM and REMS, which it does. From this model we hypothesize that loss of the orexin neurons in narcolepsy disinhibits the MCH neurons resulting in sleepiness and cataplexy. Thus, MCH antagonists could help ameliorate narcoleptic symptoms. In wildtype mice MCH neuron stimulation should also decrease addiction since it is decreasing the orexin tone. Ach, acetylcholine; BF, basal forebrain; CRF, corticotrophin releasing factor; DA, dopamine; DR, dorsal raphe; glut, glutamate; HA, histamine;LC, locus coeruleus; LH, lateral hypothalamus; MnPO, median preoptic area; NE, norepinephrine; NPY, neuropeptide Y; SLD, sublateral dorsal nucleus;TMN, tuberomammillary nucleus; vlPAG, ventral lateral periaqueductal gray; 5HT, serotonin.

CITATION

Pelluru D; Konadhode RR; Shiromani PJ. MCH neurons are the primary sleep-promoting group. SLEEP 2013;36(12):1779-1781.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. This work was supported by NIH grants MH055772, NS079940, NS084477 and Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Carlos Blanco-Centurion and Dr. Meng Liu for discussions.

Footnotes

A response to Fraigne JJ, Peever JH, Jones BE, Hassani OK, McGinty D, Alam N, Luppi PH, Peyron C, and Fort P. Critical Topics Forum. Sleep 2013;36:1767–1776.

REFERENCES

- 1.Szymusiak R. New insights into melanin concentrating hormone and sleep: a critical topics forum. Sleep. 2013;36:1765–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fraigne JJ, Peever JH. Melanin-concentrating hormone neurons promote and stabilize sleep. Sleep. 2013;36:1767–8. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones BE, Hassani OK. The role of Hcrt/Orx and MCH neurons in sleep-wake state regulation. Sleep. 2013;36:1769–72. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGinty D, Alam N. MCH neurons: the end of the beginning. Sleep. 2013;36:1773–4. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luppi PH, Peyron C, Fort P. Role of MCH neurons in paradoxical (REM) sleep control. Sleep. 2013;36:1775–6. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blouin AM, Fried I, Wilson CL, et al. Human hypocretin and melanin-concentrating hormone levels are linked to emotion and social interaction. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1547. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konadhode RR, Pelluru D, Blanco-Centurion C, et al. Optogenetic stimulation of MCH neurons increases sleep. J Neurosci. 2013;33:10257–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1225-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jego S, Glasgow SD, Herrera CG, et al. Optogenetic identification of a rapid eye movement sleep modulatory circuit in the hypothalamus. Nat Neurosci. 2013 Aug 22; doi: 10.1038/nn.3522. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luppi PH, Clement O, Fort P. Paradoxical (REM) sleep genesis by the brainstem is under hypothalamic control. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:786–92. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherin JE, Shiromani PJ, McCarley RW, Saper CB. Activation of ventrolateral preoptic neurons during sleep. Science. 1996;271:216–9. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szymusiak R, Gvilia I, McGinty D. Hypothalamic control of sleep. Sleep Med. 2007;8:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van den Pol AN, Acuna-Goycolea C, Clark KR, Ghosh PK. Physiological properties of hypothalamic MCH neurons identified with selective expression of reporter gene after recombinant virus infection. Neuron. 2004;42:635–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00251-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.John J, Wu MF, Boehmer LN, Siegel JM. Cataplexy-active neurons in the hypothalamus: implications for the role of histamine in sleep and waking behavior. Neuron. 2004;42:619–34. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00247-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portas CM, Thakkar M, Rainnie D, McCarley RW. Microdialysis perfusion of 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin (8-OH-DPAT) in the dorsal raphe nucleus decreases serotonin release and increases rapid eye movement sleep in the freely moving cat. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2820–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02820.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerashchenko D, Salin-Pascual R, Shiromani PJ. Effects of hypocretinsaporin injections into the medial septum on sleep and hippocampal theta. Brain Res. 2001;913:106–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02792-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao Y, Lu M, Ge F, et al. Regulation of synaptic efficacy in hypocretin/ orexin-containing neurons by melanin concentrating hormone in the lateral hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9101–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1766-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherin JE, Elmquist JK, Torrealba F, Saper CB. Innervation of histaminergic tuberomammillary neurons by GABAergic and galaninergic neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus of the rat. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4705–21. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04705.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur S, Thankachan S, Begum S, Liu M, Blanco-Centurion C, Shiromani PJ. Hypocretin-2 saporin lesions of the ventrolateral periaquaductal gray (vlPAG) increase REM sleep in hypocretin knockout mice. PloS One. 2009;4:e6346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao XB, Ghosh PK, van den Pol AN. Neurons synthesizing melanin-concentrating hormone identified by selective reporter gene expression after transfection in vitro: transmitter responses. J Neurophys. 2003;90:3978–85. doi: 10.1152/jn.00593.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang H, van den Pol AN. Rapid direct excitation and long-lasting enhancement of NMDA response by group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation of hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11560–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2147-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kong D, Vong L, Parton LE, et al. Glucose stimulation of hypothalamic MCH neurons involves K(ATP) channels, is modulated by UCP2, and regulates peripheral glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2010;12:545–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]