SUMMARY

Polymorphisms in the essential autophagy gene Atg16L1 have been linked with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease, a major type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Although the inability to control intestinal bacteria is thought to underlie IBD, the role of Atg16L1 during extracellular intestinal bacterial infections has not been sufficiently examined and compared to the function of other IBD susceptibility genes such as Nod2, which encodes a cytosolic bacterial sensor. We find that Atg16L1 mutant mice are resistant to intestinal disease induced by the model bacterial pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. An Atg16L1 deficiency alters the intestinal environment to mediate an enhanced immune response that is dependent on monocytic cells, but this hyper-immune phenotype and protective effects are lost in Atg16L1/Nod2 double mutant mice. These results reveal an immuno-suppressive function of Atg16L1, and suggest that gene variants affecting the autophagy pathway may have been evolutionarily maintained to protect against certain life-threatening infections.

INTRODUCTION

An over exuberant response to intestinal bacteria has long been suspected to underlie inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), yet demonstrating a causative role for any specific infectious agent has been challenging. Instead, great emphasis has been placed on understanding genetic susceptibility with the hope of identifying pathways that can be targeted for therapeutic intervention. This effort is exemplified by large-scale population genetic studies that have implicated several genes related to autophagy, a process by which cytosolic material is enclosed in a double-membrane vesicle and targeted to the lysosome for degradation and recycling (Hubbard and Cadwell, 2011). Most notably, several polymorphisms within or near the essential autophagy gene Atg16L1 increase the risk of acquiring Crohn’s disease, one of the two major types of IBD (Jostins et al., 2012). As such, examining the function of Atg16L1 in the complex intestinal environment is likely to yield unique insight into mucosal immunity and the obscure origin of IBD.

We previously generated mice in which the Atg16L1 locus is disrupted by a gene trap cassette leading to reduced Atg16L1 expression and autophagy in all tissues examined (Cadwell et al., 2008). Upon infection with murine norovirus (MNV), these Atg16L1 hypomorph (Atg16L1HM) mice develop intestinal abnormalities including aberrant granule formation by Paneth cells, an intestinal epithelial cell type with antimicrobial function (Cadwell et al., 2010). This observation in Atg16L1HM mice allowed us to identify similar Paneth cell defects in Crohn’s disease patients homozygous for the highly prevalent T300A disease variant of Atg16L1 (Cadwell et al., 2008). While these results suggest that Atg16L1 mutation can mediate specific disease manifestations downstream of an intestinal infection, it is uncertain whether this susceptibility to a virus can be extended to common bacterial infections. Moreover, it is unclear why disease variants of Atg16L1 and other autophagy genes occur at high frequency in the human population if interfering with this pathway increases susceptibility to intestinal infections.

Nod2, which encodes a cytosolic bacterial sensor, was identified as a Crohn’s disease susceptibility gene prior to the association of autophagy with this disease (Hugot et al., 2001; Ogura et al., 2001). Nod2−/− mice are vulnerable to oral infection with Citrobacter rodentium, a relative of pathogenic E. coli that induces many of the histological features associated with IBD (Kim et al., 2011). Nod2−/− mice have impaired recruitment of monocytes to the intestine in response to C. rodentium due to reduced local production of CCL2, thereby resulting in prolonged bacterial shedding and inflammation. In vitro experiments have also shown that activation of Nod2 recruits Atg16L1 to the site of bacterial entry, a process that can contribute to autophagy-mediated degradation of E. coli (Cooney et al., 2010; Homer et al., 2010; Lapaquette et al., 2012; Travassos et al., 2010). However, Atg16L1HM mice display decreased urinary tract infection by a uropathogenic strain of E. coli (UPEC), suggesting that this gene has unappreciated functions in vivo (Wang et al., 2012). In this study, we investigated whether Atg16L1 deficiency would mimic Nod2 deficiency and increase susceptibility to C. rodentium.

RESULTS

Atg16L1 deficiency confers resistance to C. rodentium

To directly compare Nod2 and Atg16L1 during intestinal infection, wild-type (WT), Nod2−/−, and Atg16L1HM mice were orally inoculated with 2×109 colony forming units (CFU) of C. rodentium. Consistent with previous findings, Nod2−/− mice lost significant body weight with 50% succumbing to lethality, and surviving mice continued to shed bacteria a month post-infection (Figure 1A–1C). However, Atg16L1HM mice displayed accelerated clearance with ~1000-fold reduction in C. rodentium numbers compared to WT by day 15 (Figure 1A). At this time point, C. rodentium associated with colonic tissue was undetectable in 8 out of 12 Atg16L1HM mice compared to 102–106 CFU recovered from the same amount of tissue from WT (Figure S1A). Similar observations were made when comparing the amount of bacteria present in the cecum (Figure S1B). This decrease in intestinal C. rodentium was not due to an increase in dissemination out of the gastrointestinal tract since similar amounts of bacteria were observed in the spleen and liver of WT and Atg16L1HM mice (Figure S1C, D).

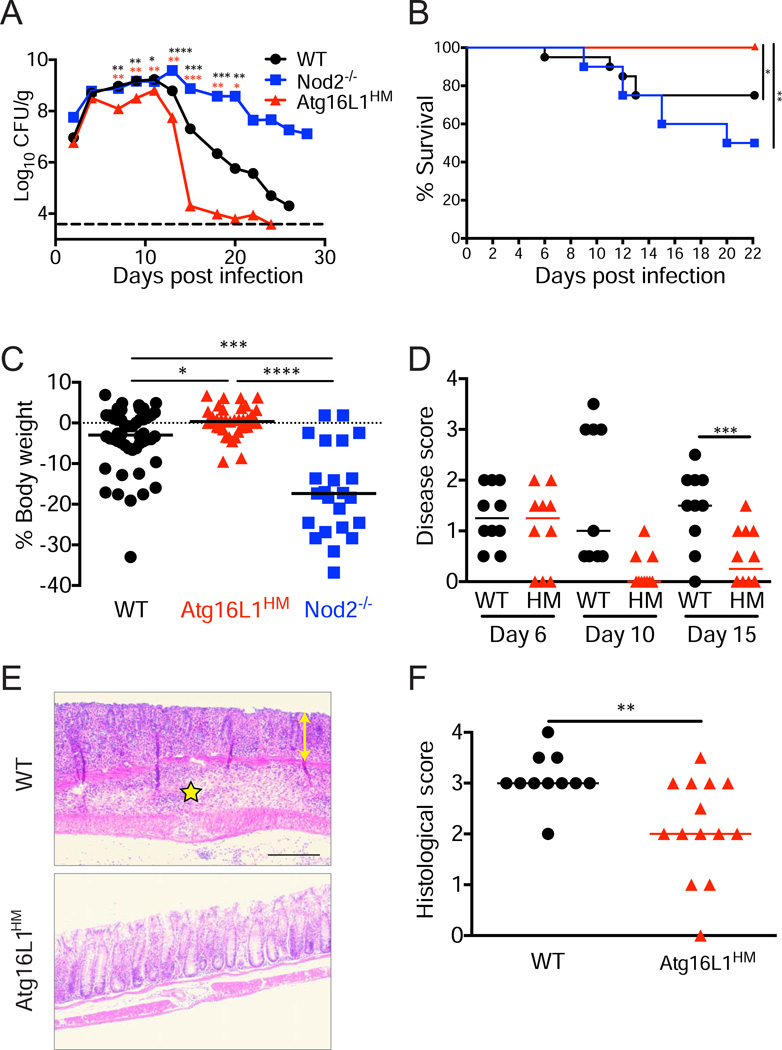

Figure 1. Atg16L1 mutant mice are resistant to C. rodentium.

(A) Bacteria recovered from stool over time from WT, Atg16L1HM, and Nod2−/− mice inoculated with C. rodentium. Dashed line indicates limit of detection. n>10 mice/genotype.

(B) Survival curve of infected mice. n=16–20 mice/genotype.

(C) Quantification of weight change for mice in (B) on day 15 relative to initial body weight.

(D) Quantification of disease for mice in (B) on indicated days.

(E) Representative H+E-stained colonic sections on day 15. Yellow double-headed arrow denotes epithelial hyperplasia, crypt distortion, and goblet cell depletion; and yellow star indicates region with marked intramural edema and inflammatory infiltrates that focally extend into the muscularis and serosal surface. Scale bar=100 µm.

(F) Quantification of pathologies observed in colon. n=11–14 mice/genotype.

Data points in (A) and bars in (C) represent median. Bars in (D) and (F) represent mean. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Red and black asterisks in (A) denote significant differences when comparing Atg16L1HM to WT and Nod2−/− respectively.

See also Figure S1

This divergent effect of Nod2 and Atg16L1 deficiency was also apparent when measuring disease. In contrast to WT and Nod2−/− mice, Atg16L1HM mice displayed 100% survival, and fewer presented weight loss and diarrheal disease (Figure 1B–D). Despite susceptibility to virus-mediated pathologies, Atg16L1HM mice were protected from the inflammatory lesions and shortening of the colon typically induced by C. rodentium (Figure 1E, 1F, S1E, and S1F). These results indicate that, in striking contrast to Nod2, Atg16L1 deficiency confers considerable protection from C. rodentium infection and subsequent disease.

It is possible that resistance is an indirect effect of Atg16L1 mutation on commensal bacteria since C. rodentium is sensitive to the composition of other bacteria in the intestine (Ivanov et al., 2009; Wlodarska et al., 2011). As previously reported (Kamada et al., 2012), we found that germfree WT mice that lack commensal bacteria display high degree of bacterial shedding with only modest weight loss (Figure S1G and S1H). In comparison, germfree Atg16L1HM mice still had significantly reduced infection (Figure S1G), indicating that Atg16L1 mutation can increase resistance in the absence of commensal bacteria. Atg16L1 could also be required for changes to the epithelium that are necessary for bacterial adherence such as cytoskeletal rearrangement (Mundy et al., 2005). However, such a direct subversion of the host machinery is unlikely since Atg16L1 deficiency did not alter the amount of bacteria recovered in an in vitro binding and infection assay (Figure S1I). Additionally, WT and Atg16L1HM mice had the same amount of tissue-associated bacteria earlier on day 6 post-infection (Figure S1F). These findings indicate that the ability to establish an adherent infection is not compromised by Atg16L1 mutation, and cannot account for the immense reduction in shedding and tissue-associated bacteria at later time points.

Atg16L1 deficiency is associated with a hyper-immune transcriptional response

A previous microarray analysis found that C. rodentium infection is associated with a large-scale transcriptional response in the colon that changes over time (Spehlmann et al., 2009). To determine the effect of Atg16L1 deficiency on this transcriptional response, we performed RNA deep sequencing (RNA-Seq) of colonic tissue from WT and Atg16L1HM mice on day 0, 6, and 15 post-infection with 3–4 biological replicates per condition. We compared genes that were differentially regulated by >1.5-fold (p<0.05) between time points (day 0 vs 6, and day 0 vs 15) and genotype (Figure 2, Table S1). As expected, bacterial infection of WT mice led to increased expression of almost all the genes that were identified as top hits in the previous study (Table S1). While we detected an overlap between WT and Atg16L1HM samples in the expression of genes that were induced, many of these changes were genotype specific, and the overlap was not as pronounced until day 15 post-infection (Figure 2A and 2B). Remarkably, there were 150 differentially regulated genes when comparing uninfected WT and Atg16L1HM mice, 110 of which displayed significantly increased expression due to Atg16L1 deficiency (Table S1). A substantial proportion of these genes are associated with type I and II interferons (IFNs) including those encoding classic markers such as Isg15 and 2’–5’ oligoadenylate synthetases, signaling molecules (Stat1, Stat2, Irf9, Irf7), cytokines (Cxcl9 and Ccl5), and IFN-inducible GTPases (Irg, Mx, and GBP family members). Pathway analysis of this gene set confirmed that there is an over-representation of genes assigned to the functional categories of defense response, innate immunity, antigen presentation, IFN-inducible GTPase, and response to bacterium (Figure 2C).

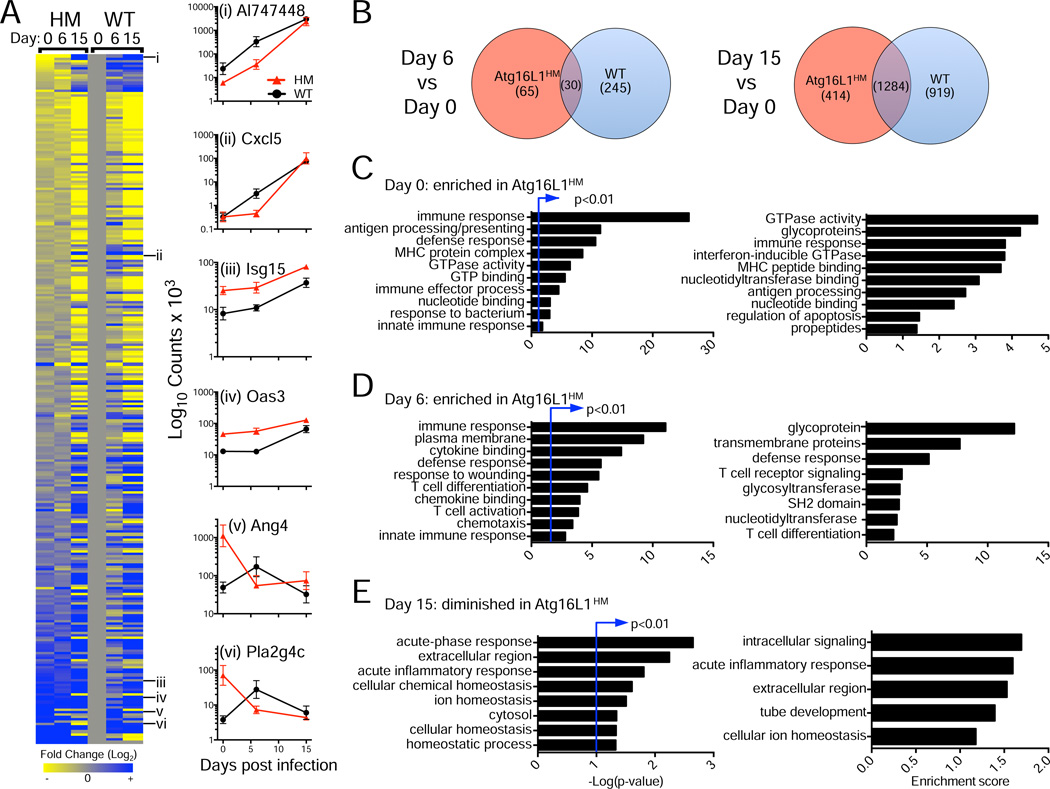

Figure 2. Atg16L1 deficiency is associated with a hyper-immune transcriptional response in the intestine.

(A) RNA-Seq analysis of whole colonic tissue from WT and Atg16L1HM mice on day 0, 6, and 15 post-infection. Heat map displays ratio of normalized expression values of genes associated with immune responses for each sample vs WT on day 0. Right panels show examples of patterns in which expression is induced in both WT and Atg16L1HM (i, ii); elevated in uninfected Atg16L1HM and remain high (iii, iv); and elevated initially in uninfected Atg16L1HM but induced in WT after infection (v, vi). Data is shown as counts of RNA base pairs, mean+/−SEM.

(B) Venn diagram showing number of genes that display increased expression on day 6 or 15 in Atg16L1HM, WT, or both compared to day 0 samples of the same genotype.

(C) Gene ontology (GO) analysis of transcripts enriched in Atg16L1HM compared to WT on day 0.

(D) GO analysis of transcripts enriched in Atg16L1HM compared to WT on day 6.

(E) GO analysis of transcripts enriched in WT compared to Atg16L1HM on day 15.

GO terms with the highest significance (left) and enrichment (right) are shown for (C), (D), and (E).

See also Table S1.

Atg16L1HM mice continued to display this increased expression of immune-related genes on day 6 post-infection, and there was also a wound-healing signature that may reflect an accelerated resolution (Figure 2D). In contrast on day 15 post-infection, WT mice displayed increased expression of the inflammatory genes Reg3b, Reg3g, Saa3, Lcn2, and Retnlb relative to Atg16L1HM mice reflecting the longer disease course (Figure 2E). Finally, there were numerous examples of antimicrobial genes that displayed increased expression earlier in Atg16L1HM samples compared to WT (Figure 2A, Table S1). These results indicate that the Atg16L1-deficient intestinal environment has a hyper-immune transcriptional response both prior to and during C. rodentium infection that is consistent with the accelerated disease course.

Protection due to Atg16L1 mutation is independent of the T helper cell response and neutrophils

Previous studies have shown that immune responses mediated by CD4+ T cells, neutrophils, and monocytes are among the most important during C. rodentium infection (Bry et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2003; Spehlmann et al., 2009). C. rodentium infection was also previously shown to induce a Th17 response that is dependent on epithelial apoptosis induced by bacterial virulence factors EspF and MAP (Torchinsky et al., 2009). However, we did not detect differences in the amount of epithelial cell death or number of T cells in colonic sections from infected WT and Atg16L1HM mice (Figure S2A and S2B). We also observed similar amounts of lamina propria CD4+ T cells expressing IFNγ, IL-17, IL-22, and FoxP3 and innate lymphoid cells (Figure 3A, 3B, and S2C–E). Also, Atg16L1HM mice displayed reduced bacterial numbers compared to WT when infected by ΔEspF and ΔMap bacterial mutants (Figure S2F and S2G). Although this result suggests that protection conferred by Atg16L1 deficiency is not specific to C. rodentium, we previously did not detect enhanced resistance to oral Listeria monocytogenes infection (Cadwell et al., 2008), and Atg16L1HM mice did not have enhanced resistance to Yersinia enterocolitica or pseudotuberculosis (Figure S2H and S2I). Thus, attenuated strains of C. rodentium are sensitive to Atg16L1 deficiency, but the enhanced protection displays some pathogen-specificity.

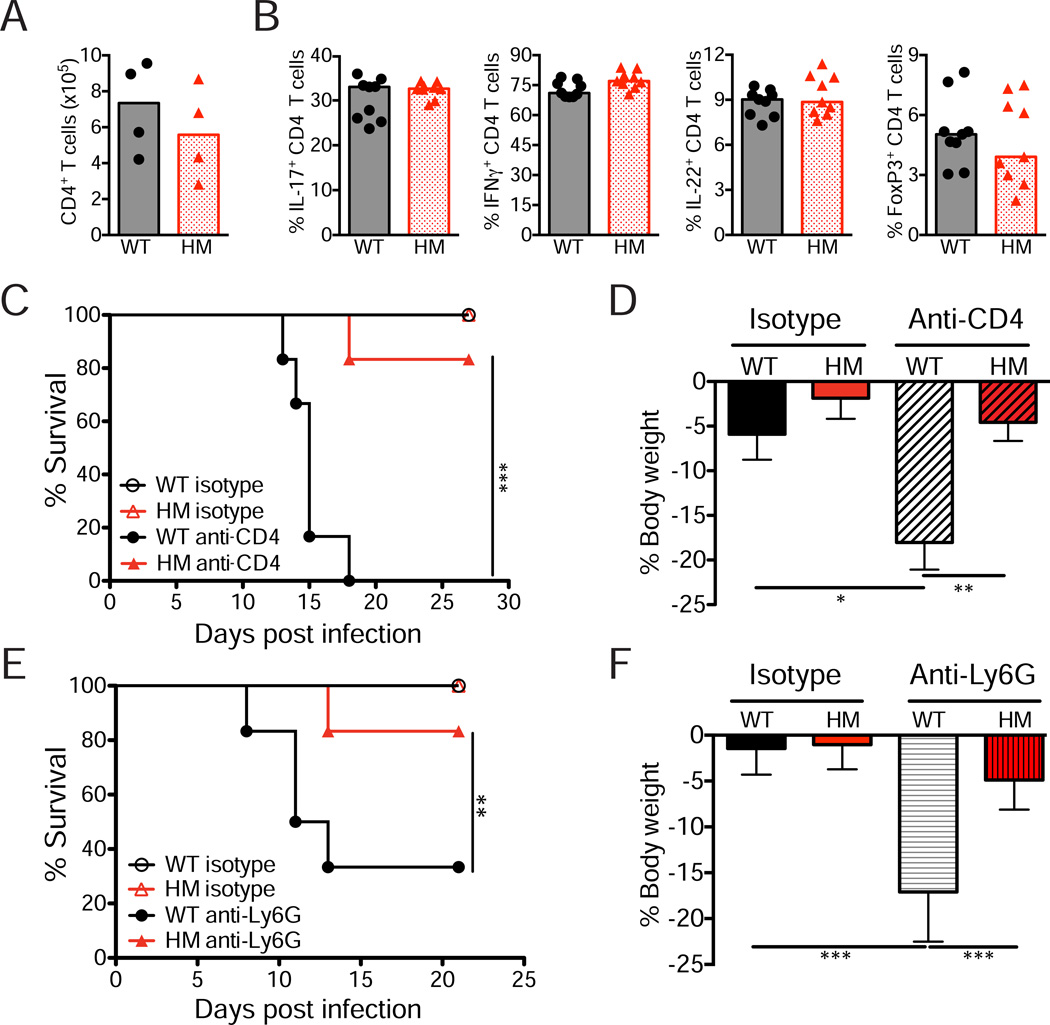

Figure 3. Protection conferred by Atg16L1 deficiency is independent of the T helper cell and neutrophil responses.

(A) Quantification by flow cytometry of the total number of CD4+ T cells (CD4+ TCRβ+) in the colonic lamina propria on day 15 post-infection. n=4 mice/genotype.

(B) Quantification of the proportion of CD4+ T cells expressing the indicated differentiation markers after PMA/ionomycin treatment. n=9 mice/genotype.

(C) Survival curve of infected WT and Atg16L1HM mice injected with anti-CD4 or isotype control antibodies. n=6 mice/condition.

(D) Quantification of weight change observed in mice from (C) on day 13 relative to initial body weight.

(E) Survival curve of infected WT and Atg16L1HM mice injected with anti-Ly6G or isotype control antibodies. n=6 mice/group.

(F) Quantification of weight change observed in mice from (E) on day 8 relative to initial body weight.

Bars in (A), (B), (D), and (F) represent mean. Error bars in (D) and (F) represent SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

See also Figure S2.

Next, we examined whether CD4+ T cells and neutrophils are essential for the enhanced resistance of Atg16L1HM mice using anti-CD4 and anti-Ly6G depleting antibodies respectively (Figure S2J and S2K). While 100% of WT mice depleted of CD4+ T cells during infection succumbed to lethality, similarly treated Atg16L1HM mice were protected from weight loss and almost all survived (Figure 3C and 3D). Likewise, neutrophil-depletion significantly increased lethality, weight loss, and bacteria burden in infected WT but not Atg16L1HM mice (Figure 3E, 3F, and S2L). These results indicate that T helper cells and neutrophils are dispensable for resistance mediated by Atg16L1 mutation despite the essential role of these cell types in WT mice during infection.

Protection due to Atg16L1 mutation is dependent on monocytes and Nod2

To assess the role of macrophages and their precursor monocytes, infected mice were injected with clodronate liposomes that deplete this lineage and compared to control mice that received liposomes only. The specificity of depletion was confirmed in both uninfected and infected mice by flow cytometry (Figure S3A and S3B). We found that clodronate treatment of Atg16L1HM mice infected with C. rodentium led to a significant decrease in survival (Figure 4A). Clodronate liposome injection in the absence of infection did not cause lethality indicating that the survival defect was not due to the treatment itself (Figure S3C). Also, monocyte depletion increased bacterial shedding in Atg16L1HM mice to levels similar to that of monocyte-depleted WT mice, both prior to lethality on day 8 and in surviving mice on day12 (Figure 4B and 4C). These experiments demonstrate that monocytic cells are essential for the decrease in disease and bacterial burden due to Atg16L1 deficiency.

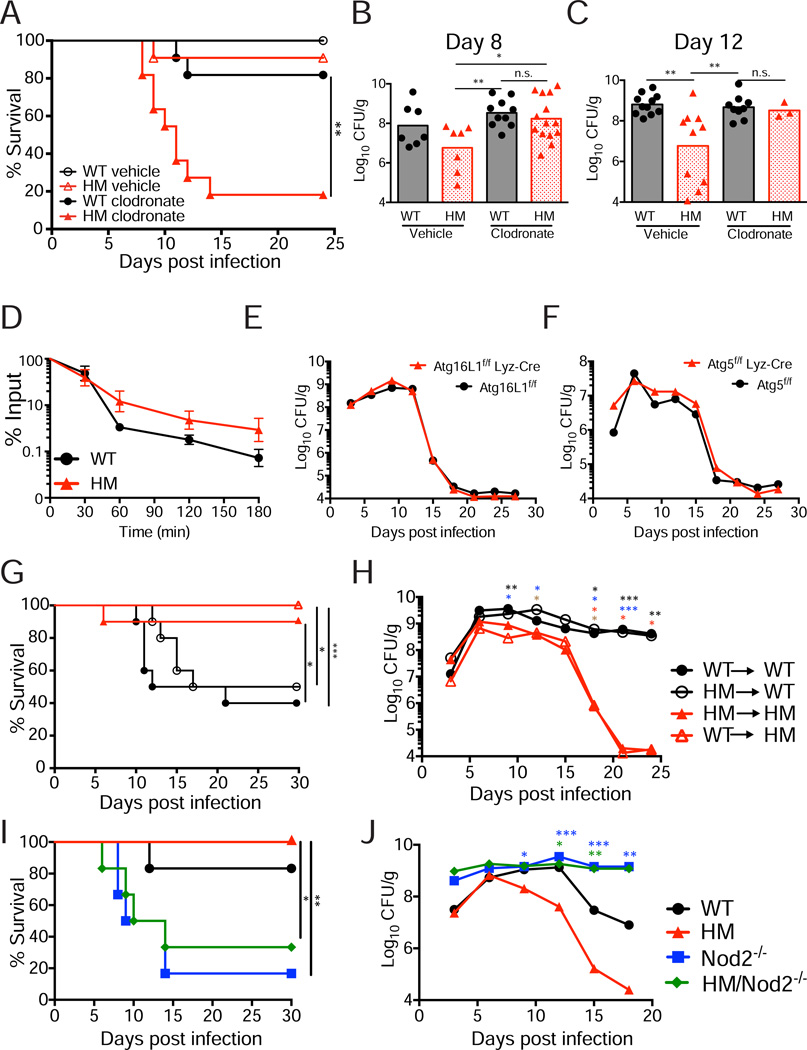

Figure 4. Resistance to C. rodentium in Atg16L1 mutant mice is dependent on monocytes and Nod2.

(A) Survival curve of infected WT and Atg16L1HM mice injected with clodronate liposomes or liposomes only (vehicle control). n=11 mice/group.

(B) Quantification of bacteria in stool from mice in (A) on day 8 post-infection.

(C) Quantification of bacteria in stool from surviving mice in (A) on day 12.

(D) C. rodentium was incubated with WT and Atg16L1HM peritoneal macrophages and internalized bacteria were recovered at indicated time points after incubation. Average of 3 experiments, n=6 mice/genotype (2 per experiment).

(E) Quantification of bacteria recovered from stool over time from Atg16L1f/f and Atg16L1f/fLyz-Cre mice inoculated with C. rodentium. n=7 Atg16L1f/f and 14 Atg16L1f/fLyz-Cre mice.

(F) Quantification of bacteria recovered from stool over time from Atg5f/f and Atg5f/fLyz-Cre mice inoculated with C. rodentium. n=13 Atg5f/f and 11 Atg5f/fLyz-Cre mice.

(G) Survival curve of chimeric mice inoculated with C. rodentium. n=10 mice/group.

(H) Quantification of bacteria recovered from stool over time from the mice in (G).

(I) Survival curve of WT, Atg16L1HM, Nod2−/−, and Atg16L1HM/Nod2−/− mice inoculated with C. rodentium. n≥5 mice/genotype.

(J) Quantification of bacteria from stool over time from the mice in (I).

Bars in (B) and (C) and data points in (E), (F), (H), and (J) represent median. Data points in (D) represent mean+/−SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Asterisks in (H) denote significant differences comparing: WT→WT vs WT→HM (black), HM→WT vs WT→HM (blue), WT→WT vs HM→HM (red), and HM→WT vs HM→HM (brown). Blue and green asterisks in (J) denote Atg16L1HM compared to Nod2−/− and Atg16L1HM/Nod2−/− respectively.

See also Figure S3.

We did not detect a difference in the number of intestinal monocytic cells in uninfected WT and Atg16L1HM mice by either flow cytometry or immuno-histochemistry (IHC) (Figure S3D–G). While C. rodentium infection caused an overall increase, especially in inflammatory Ly6Chi monocytes, this increase was similar in WT and Atg16L1HM mice (Figure S3E–G). These results suggest monocyte function rather than total numbers may be altered in this setting. However, a cell-intrinsic effect of Atg16L1 deficiency in enhancing monocyte function is unlikely since autophagy has been shown to contribute to C. rodentium killing during in vitro infection of peritoneal macrophages (Su et al., 2012). We performed a similar experiment and also found that C. rodentium killing is impaired, rather than enhanced, in peritoneal macrophages harvested from Atg16L1HM mice (Figure 4D). To confirm this lack of a cell-intrinsic role of Atg16L1 in monocytic cells in vivo, we infected mice with cell type-specific deletion of Atg16L1 in myeloid cells generated by breeding mice expressing the Cre recombinase under the lysozyme M promoter with mice that have a loxP-flanked Atg16L1 allele (Atg16L1fl/fl Lyz-Cre). Atg16L1fl/fl Lyz-Cre mice did not display differences in bacterial shedding compared to Atg16L1fl/fl controls (Figure 4E). We also examined mice with a similar deletion in the Atg16L1-binding partner Atg5 (Atg5fl/fl Lyz-Cre) since these mice display decreased bacteriuria following bladder infection by UPEC (Wang et al., 2012). Atg5fl/fl Lyz-Cre mice also did not display altered resistance to C. rodentium (Figure 4F). These results indicate that Atg16L1 and Atg5 deletion in myeloid cells is not sufficient.

Next, we generated and infected bone marrow chimeras to differentiate between Atg16L1 function in the hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic compartments. We found that the recipient Atg16L1HM mice displayed decreased lethality, weight loss, and bacterial burden regardless of the bone marrow source when compared to WT recipients reconstituted with WT or Atg16L1HM bone marrow (Figure 4G, 4H, and S3H). Together with the above findings, these results indicate that Atg16L1 deficiency in a non-myeloid cell type mediates enhanced resistance, even though this resistance is dependent on the presence of monocytes. These results also indicate that the mechanism by which Atg16L1 deficiency confers resistance towards C. rodentium in the intestine differs from the mechanism of resistance towards urinary tract infection by the related pathogen UPEC, which is associated with autophagy in the myeloid compartment.

Finally, we hypothesized that bacterial recognition by Nod2 would be required for the enhanced protection displayed by Atg16L1HM mice since Nod2−/− mice have impaired recruitment of monocytes to the site of bacterial infection. To test this hypothesis, we generated Atg16L1HM/Nod2−/− double mutant mice. As predicted by the monocyte-depletion experiments, the advantage due to Atg16L1 mutation was lost in the absence of Nod2. Atg16L1HM/Nod2−/− mice displayed a similar degree of lethality, weight loss, and bacterial shedding as seen in Nod2−/− mice (Figure 4I, 4J, and S3I). To confirm these results, we also generated Atg16L1HM mice deficient in the Nod2 signaling adaptor protein Rip2 (Atg16L1HM/Rip2−/− mice) and made similar observations (Figure S3J). These results indicate that the susceptibility from Nod2-deficiency is dominant over the benefit of Atg16L1 deficiency.

DISCUSSION

Despite the likely involvement of aberrant host-microbe interactions in the pathogenesis of IBD, the role of Atg16L1 during an enteric infection has not been sufficiency examined in vivo. We have found that Atg16L1 mutation leads to significant protection from C. rodentium infection and the inflammatory intestinal disease caused by this model pathogen. This protection is independent of a role for Atg16L1 in mediating bacterial adherence or regulating commensal bacteria, but is associated with a hyper-immune transcriptional signature that precedes and continues during the early part of infection. The degree of resistance conferred by Atg16L1 deficiency is such that it prevents lethality in infected mice depleted of CD4+ T cells and neutrophils. Instead, the enhanced protection provided by Atg16L1 mutation is dependent on monocytes and Nod2. All together, our results indicate that Atg16L1 has an unexpected role in suppressing a beneficial immune response during an enteric bacterial infection.

Given the antibacterial function typically attributed to autophagy genes, it is unlikely that Atg16L1 deficiency is beneficial under all circumstances. Atg16L1HM mice did not display enhanced resistance when infected by Yersinia species, which could reflect the difference in strategies used by these pathogens and C. rodentium to establish an infection. Both Yersinia species examined have been shown to efficiently block autophagy-mediated degradation when engulfed by macrophages (Deuretzbacher et al., 2009; Moreau et al., 2010). It is possible that Atg16L1 deficiency confers protection towards bacteria that are less capable of surviving within macrophages, and instead must avoid engulfment for productive infection. Also, it has become apparent that Atg16L1 and related autophagy genes have a highly cell type-specific function. Intestinal epithelium-specific deletion of autophagy genes increase susceptibility rather than resistance to C. rodentium and Salmonella (Benjamin et al., 2013; Inoue et al., 2012). In our experiments, this adverse effect of autophagy inhibition is masked by the protective effect of Atg16L1 deficiency, which may explain why C. rodentium infection led to high lethality in Atg16L1HM mice following monocyte depletion.

This dependence on monocytes for resistance was somewhat unexpected since autophagy is important for C. rodentium killing by monocytic cells in vitro (Su et al., 2012). We found that Atg16L1 deficiency in monocytic cells in vitro or in vivo did not lead to enhanced resistance to C. rodentium. Instead, experiments with chimeric mice indicated that Atg16L1 mutation in the non-hematopoietic compartment mediates enhanced resistance. Nod2 was also shown to function predominantly in the non-hematopoietic compartment, most likely in stromal cells, to act on monocytes in a cell-extrinsic manner (Kim et al., 2011). However, unlike in Nod2−/− mice, monocyte recruitment was not altered in Atg16L1HM mice. In the context of these findings, it is interesting that we detected higher expression of immune-related genes in intestinal tissue harvested from Atg16L1HM mice. Many of these genes are associated with IFNs as well as other factors related to activation of monocytic cells. For these reasons, we favor a model in which Atg16L1 deficiency in the intestinal tissue primes the environment for an enhanced immune response mediated by monocytes.

The identification of Atg16L1 and Nod2 as susceptibility genes is frequently cited as evidence that a deficient innate immune response to bacteria causes Crohn’s disease. The important role of Atg16L1 and Nod2 in promoting defense against pathogens is undeniable. Nevertheless, our findings reveal an immuno-suppressive function of Atg16L1 in the intestine that requires further investigation. If Atg16L1 suppresses a beneficial inflammatory response, does it also prevent unnecessary or harmful responses to enteric infection? This may be the case, since in our previous study we found the same Atg16L1HM mice develop IBD-related pathologies in response to norovirus infection (Cadwell et al., 2010). An exaggerated monocyte response may be less desirable when the infection is not life threatening. Our results also indicate that Nod2 and Atg16L1 could have independent contributions during bacterial infection in addition to Nod2-mediated autophagy in which these genes function together.

Finally, an outstanding question has been what selective pressure has led to the maintenance of polymorphisms in Atg16L1 and other autophagy genes that increase the risk of acquiring inflammatory disorders. C. rodentium has been an important model pathogen to understand the immune response to pathogenic E. coli that cause a range of illnesses including pediatric diarrhea, which is often lethal in underdeveloped parts of the world. Although specific gene variants such as the prevalent T300A allele of Atg16L1 and mutations in the promoter region of Irgm require further characterization, it is conceivable that we have maintained these variants to enhance immunity during common enteric infections. With our modern life style that has seen improved sanitation and healthcare, gene variants that enhance immunity may have become less of a necessity and more of a burden that predisposes to complex inflammatory disorders.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice

All mice were on a C57BL/6 background. High density microsatellite mapping (Rheumatic Disease Core, Washington University School of Medicine) was used for backcrossing previously described Atg16L1HM mice (HM1 strain) (Cadwell et al., 2008). Nod2−/− mice were previously reported (Kim et al., 2008). Rip2−/− mice were from Eric Pamer (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center). Atg16L1HM/Nod2−/− and Atg16L1HM/Rip2−/− mice were generated by crossing Atg16L1HM and Nod2−/− or Rip2−/− mice and breeding heterozygous progeny to each other. WT refers to C57BL/6J mice purchased from Jackson that were bred onsite to generate animals for experimentation. Atg5f/f and Atg16L1f/f Lyz-Cre mice were from Skip Virgin (Washington University School of Medicine). Bone marrow chimeras using Atg16L1HM donors and recipients (Wang et al., 2012) were infected 8 weeks after transfer at which point ~96% of the peripheral blood cells were confirmed to be of donor origin.

Bacterial infection

Previously described C. rodentium strain DBS100 and isogenic mutants ΔEspF and ΔMap (Torchinsky et al., 2009) were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani broth with shaking at 37°C and diluted to OD = 1 followed by an additional 5 hours of growth. Bacterial density was confirmed by dilution plating. 8–12 week old gender-matched mice were inoculated by oral gavage with 2×109 CFU resuspended in 100µl PBS. Severity of disease was quantified through a scoring system in which individual mice received a score of 1 for each of the following: hunched posture, inactivity, ruffled fur, and diarrhea; mice received an additional score between 0 and 2 for weight loss calculated as percent of initial body weight with a score of 0 = 0–5%, 0.5 = 6%–10%, 1 = 11–15%, 1.5 = 16–20%, and 2 = greater than 20% loss. For quantification of bacterial shedding, stool pellets from individual mice were weighed, homogenized in PBS, and plated in serial dilutions on MacConkey agar. Y. psuedotuberculosis (YPIII with pIB1) and enterocolitica (AJD3) were from Andrew Darwin and prepared similarly with appropriate antibiotics. Last observation was carried forward for mice that died in longitudinal studies.

Tissue collection and analyses

H+E-stained colonic sections were prepared as previously described (Cadwell et al., 2010). Pathology was quantified blind by a pathologist (Y.D.) using a previously described scoring system (Asseman et al., 2003). TUNEL, anti-CD3, and anti-F4/80 staining of colonic sections was performed by the NYU IHC Core. For quantification of tissue-associated bacteria, 2cm of the distal colon was flushed with PBS and homogenized in PBS. For cecum, the entire contents were flushed with PBS and homogenized. To isolate lamina propria cells, small pieces of colons washed with HBSS were incubated at 37°C with shaking in HBSS containing 1mM DTT and 5mM EDTA for 15 min, 1mM EDTA HBSS for 10 min, washed with HBSS, and then incubated in HBSS containing 0.1µ/ml dispase (Worthington), 0.1mg/ml DNase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1mg/ml collagenase (Roche) for 25 min. Digested tissues were filtered and washed twice with RPMI containing 10% FCS. Isolated cells were re-suspended in 40% Percoll (Pharmacia Biotech), layered onto 80% Percoll, and centrifuged at room temperature at 2200 rpm for 20 min. Cells were recovered from the interphase and washed with RPMI containing 10% FCS.

Flow cytometry

Isolated lamina propria cells were stimulated with 10ng/ml phorbol12-myristate 13-acetate and 1µg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 h in the presence of GolgiStop (BD). After stimulation cells were transferred to round bottom 96 well plates and washed twice with MACS buffer (0.5% w:v BSA, 2.5mM EDTA in PBS). Cells were resuspended in surface stain solution containing Invitrogen Fixable Live/Dead UV (1:500), anti-CD4-AF700 (1:200, BD), anti-TCRβ-PerCpCy5.5 (1:200, BD), FC Block (1:100, BD). After 15 min cells were washed twice in MACS buffer, fixed for 20 min, washed twice, and resuspended in MACS buffer. For intracellular cytokine staining cells were permeabilized (0.5% w:v saponin in MACS buffer), pelleted, then resuspended in intracellular staining solution made in permeabilization buffer containing anti-FoxP3-FITC (1:200, Biolegend), anti-IL-17A-APC (1:200, BD), anti-IFNγ-e450 (1:100, Biolegend), anti-IL-22-PE (1:200, eBioscience), FC Block (1:100, Biolegend). After 15 min cells were pelleted, washed once in permeabilization buffer, once in MACS buffer, then analyzed by LSR-II flow cytometer (BD) gated on live cells. Splenocytes were stained similarly for surface expression with the following additional antibodies: anti-Ly6G/C-APC (1:200, Biolegend), anti-F4/80-APC Cy7 (1:200, Biolegend), anti-CD11b-FITC (1:100, BD), and anti-CD11c-PE (1:200, BD).

In vitro killing assay

Peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were harvested by lavage with 10 ml DMEM 4 days after mice were injected IP with 1.5ml thioglycollate, plated and grown overnight at 37°C. PECs were then washed, counted with trypan blue exclusion, and plated at 2×105 cells per well in 48 well plates and grown overnight at 37°C. C. rodentium was added at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 and the plate was centrifuged at 1000×g for 7 min at room temperature. Bacteria were allowed to bind to cells for 30 min, then DMEM containing 1µg/ml gentamicin was added to all wells. Cells harvested at indicated time points were washed, lysed with 0.1% saponin, and bacteria were quantified by dilution plating.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism v6 was used for the following. Differences between two groups were evaluated by two-tailed unpaired t test (Figure 1F). Experiments that involved multiple comparisons were evaluated by an ANOVA with Holm-Sidak’s test (Figure 1D, 3D, 3F, S1F, S2A, S2D, S2E, S3H, S3I), unless values were not distributed normally in which case nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s test was applied (Figure 1A, 1C, 4B, 4C, 4H, 4J, S1A–D, S1G, S2F, S2G, S2L). Significance was determined after normalization or transformation when examining weight loss and bacterial numbers. Survival between groups of mice was compared using log-rank Mantel-Cox test.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Atg16L1 mutant mice are highly resistant to Citrobacter rodentium infection

Atg16L1 deficiency leads to a hyper-immune transcriptional profile in the intestine

Monocytic cells mediate an enhanced innate immune response in Atg16L1 deficient mice

Deletion of Nod2 abrogates protection due to Atg16L1 mutation

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Joel Ernst, Gretchen Diehl, Yi Yang, Dan Littman, Davida Smyth and Andrew Darwin for providing advice and reagents; Jiri Zavidil and Elisa Venturini of the NYU Genome Technology Center for deep sequencing; and Stuart Brown and Zuojian Tang of NYU Center for Health Informatics and Bioinformatics for data analysis. This research was supported by NIH grants R01 DK093668 (A.M., L.E.G., K.C.), R01 DK61707 (G.N.), T32 AI007647 (A.M., V.M.H.), K99/R00 DK080643 (I.U.M.), P30 DK052574 (I.U.M. and C.W.), F32 HL115974 (V.M.H.) and T32 AI100853 (K.M.); the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (K.C.); and the Dale F. Frey Award from the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (K.C.). The NYU IHC Core is supported in part by the NYUCI center support grant P30 CA16087.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Asseman C, Read S, Powrie F. Colitogenic Th1 cells are present in the antigen-experienced T cell pool in normal mice: control by CD4+ regulatory T cells and IL-10. Journal of immunology. 2003;171:971–978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin JL, Sumpter R, Jr, Levine B, Hooper LV. Intestinal Epithelial Autophagy Is Essential for Host Defense against Invasive Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:723–734. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bry L, Brigl M, Brenner MB. CD4+-T-cell effector functions and costimulatory requirements essential for surviving mucosal infection with Citrobacter rodentium. Infection and immunity. 2006;74:673–681. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.673-681.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, Kishi C, Kc W, Carrero JA, Hunt S, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature07416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadwell K, Patel KK, Maloney NS, Liu TC, Ng AC, Storer CE, Head RD, Xavier R, Stappenbeck TS, Virgin HW. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn's disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell. 2010;141:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney R, Baker J, Brain O, Danis B, Pichulik T, Allan P, Ferguson DJ, Campbell BJ, Jewell D, Simmons A. NOD2 stimulation induces autophagy in dendritic cells influencing bacterial handling and antigen presentation. Nat Med. 2010;16:90–97. doi: 10.1038/nm.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuretzbacher A, Czymmeck N, Reimer R, Trulzsch K, Gaus K, Hohenberg H, Heesemann J, Aepfelbacher M, Ruckdeschel K. Beta1 integrin-dependent engulfment of Yersinia enterocolitica by macrophages is coupled to the activation of autophagy and suppressed by type III protein secretion. J Immunol. 2009;183:5847–5860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer CR, Richmond AL, Rebert NA, Achkar JP, McDonald C. ATG16L1 and NOD2 Interact in an Autophagy-Dependent Antibacterial Pathway Implicated in Crohn's Disease Pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard VM, Cadwell K. Viruses, autophagy genes, and Crohn's disease. Viruses. 2011;3:1281–1311. doi: 10.3390/v3071281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O'Morain CA, Gassull M, et al. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:599–603. doi: 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J, Nishiumi S, Fujishima Y, Masuda A, Shiomi H, Yamamoto K, Nishida M, Azuma T, Yoshida M. Autophagy in the intestinal epithelium regulates Citrobacter rodentium infection. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;521:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, Lee JC, Schumm LP, Sharma Y, Anderson CA, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada N, Kim YG, Sham HP, Vallance BA, Puente JL, Martens EC, Nunez G. Regulated virulence controls the ability of a pathogen to compete with the gut microbiota. Science. 2012;336:1325–1329. doi: 10.1126/science.1222195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YG, Kamada N, Shaw MH, Warner N, Chen GY, Franchi L, Nunez G. The Nod2 Sensor Promotes Intestinal Pathogen Eradication via the Chemokine CCL2-Dependent Recruitment of Inflammatory Monocytes. Immunity. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YG, Park JH, Shaw MH, Franchi L, Inohara N, Nunez G. The cytosolic sensors Nod1 and Nod2 are critical for bacterial recognition and host defense after exposure to Toll-like receptor ligands. Immunity. 2008;28:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapaquette P, Bringer MA, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Defects in autophagy favour adherent-invasive Escherichia coli persistence within macrophages leading to increased pro-nflammatory response. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:791–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau K, Lacas-Gervais S, Fujita N, Sebbane F, Yoshimori T, Simonet M, Lafont F. Autophagosomes can support Yersinia pseudotuberculosis replication in macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1108–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundy R, MacDonald TT, Dougan G, Frankel G, Wiles S. Citrobacter rodentium of mice and man. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1697–1706. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–606. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons CP, Clare S, Ghaem-Maghami M, Uren TK, Rankin J, Huett A, Goldin R, Lewis DJ, MacDonald TT, Strugnell RA, et al. Central role for B lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells in immunity to infection by the attaching and effacing pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Infection and immunity. 2003;71:5077–5086. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5077-5086.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spehlmann ME, Dann SM, Hruz P, Hanson E, McCole DF, Eckmann L. CXCR2-dependent mucosal neutrophil influx protects against colitis-associated diarrhea caused by an attaching/effacing lesion-forming bacterial pathogen. J Immunol. 2009;183:3332–3343. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su CW, Cao Y, Zhang M, Kaplan J, Su L, Fu Y, Walker WA, Xavier R, Cherayil BJ, Shi HN. Helminth Infection Impairs Autophagy-Mediated Killing of Bacterial Enteropathogens by Macrophages. Journal of immunology. 2012 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchinsky MB, Garaude J, Martin AP, Blander JM. Innate immune recognition of infected apoptotic cells directs T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;458:78–82. doi: 10.1038/nature07781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travassos LH, Carneiro LA, Ramjeet M, Hussey S, Kim YG, Magalhaes JG, Yuan L, Soares F, Chea E, Le Bourhis L, et al. Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:55–62. doi: 10.1038/ni.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Mendonsa GR, Symington JW, Zhang Q, Cadwell K, Virgin HW, Mysorekar IU. Atg16L1 deficiency confers protection from uropathogenic Escherichia coli infection in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:11008–11013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203952109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarska M, Willing B, Keeney KM, Menendez A, Bergstrom KS, Gill N, Russell SL, Vallance BA, Finlay BB. Antibiotic treatment alters the colonic mucus layer and predisposes the host to exacerbated Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Infection and immunity. 2011;79:1536–1545. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01104-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.