Abstract

The proportion of Hispanics age sixty-five and older who are living in nursing homes rose from 5 percent in 2000 to 6.4 percent in 2005. Although segregation in nursing homes seems to have declined slightly, elderly Hispanics are more likely than their non-Hispanic white peers to reside in nursing homes that are characterized by severe deficiencies in performance, understaffing, and poor care.

Racial and ethnic differences in access to high-quality long-term care are an enduring policy issue.1,2 Recent work on disparities in the quality of care in nursing homes has shown clearly that nursing homes remain relatively segregated by race and ethnicity, and that nursing home care can be described as a tiered system in which nonwhites are concentrated in marginal-quality homes.3 Such homes tend to have serious deficiencies in staffing ratios and performance, and they are more financially vulnerable.4,5

Studies of the use of nursing homes by elderly Hispanics6 have focused on specific metropolitan areas (such as Chicago) or on Hispanics with particular health problems.7,8 Until recently, analyses of disparities in nursing home care quality between non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics have been difficult to perform, given the small numbers of elderly Hispanic nursing home residents, the small numbers of nursing homes available within or adjacent to Hispanic communities, and the lack of reliable data over time. Many researchers have assumed that because of cultural differences in family structure and expectations about aging, Hispanic nursing home residents would always constitute a very small proportion of the total nursing home population.9

Since the mid-1990s, however, the growth of the Hispanic population in the United States has exceeded all previous estimates. Demographers now expect continued dramatic growth of the Hispanic American population, which increased by 60 percent between 1990 and 2000 and now constitutes the largest U.S. minority group, at 15.1 percent of the total population.10 Whether that population growth has translated into increased use of nursing homes by elderly Hispanics, and whether there are disparities in access to high-quality nursing homes between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites needs to be examined.

This paper presents basic descriptive analyses of nursing home use over time (2000–2005) by elderly Hispanics. It compares nursing home performance levels between facilities with different proportions of Hispanic residents. It addresses four questions: (1) What are the national trends in elderly Hispanics' use of nursing homes during 2000–05? (2) How segregated are elderly Hispanic and non-Hispanic white residents in U.S. nursing homes, and did these patterns change during 2000–05? (3) Does nursing home quality performance vary by the proportion of Hispanic residents in a nursing facility? (4) Are elderly Hispanic and non-Hispanic white nursing home residents distributed disproportionately across nursing homes with varying levels of quality performance in major U.S. Metropolitan Statistical Areas?

Background: Use Of Long-Term Care By Hispanics

Hispanics have traditionally used formal long-term care services less than any other U.S. ethnic group. Hispanics are less likely than whites and blacks to live in nursing homes11 and to use home health aides.12 It's likely, however, that the growing elderly Hispanic population and the movement of Hispanic women into the workforce will make the need for long-term care services more acute among Hispanics in the near future.13

The majority of caregivers to single elderly Hispanics are adult daughters, but financial necessity and acculturation have led an increased number of young Hispanic women to work outside the home.14 The loss of traditional caregivers is occurring simultaneously with the dramatic growth of the elderly Hispanic population. More than 5 percent of the current Hispanic population is elderly—a figure that is predicted to quadruple in the next decade, rising to 4.5 million by 2010.14 Hispanics have been characterized by recent high rates of migration to the United States and by patterns of migration into and out of the country over an extended period of time. These patterns are related to family decisions about jobs, geographical location, extended kin networks, and sharing of resources.15

Although they use formal long-term care services less frequently, Hispanics have a greater rate of disability than non-Hispanic whites. Some 22 percent of Hispanics report being in poor health, compared to 17 percent of blacks, 14 percent of non-Hispanic whites, and 12 percent of Asian Americans.13 Hispanics older than age sixty-five are more likely than their non-Hispanic white and black counterparts to need assistance with everyday activities.12 Furthermore, disparities exist among Hispanic groups in relation to their use of long-term care services and their levels of disability. Elderly Puerto Rican Americans report the most restricted daily activity of any Hispanic ethnic group, followed by Mexican Americans and Cuban Americans.13 Older Puerto Ricans are most likely, and Mexican Americans least likely, of the three major Hispanic subpopulations to use in-home health services.16

Geography may account for some of these disparities, because some Hispanic subgroups may live in areas with a richer supply of long-term care services than exists in other areas. There are also differences between Hispanic groups in insurance coverage, which can limit access to some long-term care services. More than 32 percent of Hispanics are uninsured—the highest of any U.S. ethnic group.17 Mexican Americans are the most likely among Hispanics to be uninsured.18 Differences also exist among Hispanic groups with regard to immigration patterns, education, and income levels, and these demographic characteristics may themselves be related to differences in use of long-term care. Unfortunately, it is not possible, using current national data, to examine within-Hispanic ethnic differences on nursing home use and care quality. However, given the many factors affecting the use of nursing homes by elderly Hispanics and the growth in the size of this subpopulation, it is worthwhile to examine recent trends in use, and in disparities in care and quality, across nursing homes with different proportions of elderly Hispanic residents.

More than 5 percent of the current Hispanic population is elderly—a figure that is predicted to quadruple in the next decade.

Study Data And Methods

Data and Sample We used three sources of information in this analysis: (1) the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting (OSCAR) database, (2) the Minimum Data Set on nursing home resident assessments, and (3) the decennial census data and intercensus population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau. The data used in this analysis were for 2000 and 2005, which permitted us to examine trends over this five-year period. The Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting database includes measures of nursing home performance collected in the annual survey and certification process on all Medicare- or Medicaid-certified nursing homes. The Minimum Data Set includes demographic information on individual residents (including race/ethnicity) and clinical measures of physical and cognitive functioning from routine assessments. The census population data served as the denominator in computing ethnicity-specific nursing home use rates. The data sources are described more fully in an online appendix.19,20

For reasons described more fully in the appendix, we excluded nursing homes that were operated as units of acute care hospitals from this analysis (except in the calculation of nursing home use rates, for which residents in all licensed facilities were included in the numerator). Since the population of Hispanic origin— specifically Hispanic nursing home residents—tends to be concentrated in certain U.S. geographic regions, we limited our analysis to Metropolitan Statistical Areas with at least 5 percent Hispanics in the total population in both 2000 and 2005. Furthermore, given our locally defined measures of nursing home performance relative to peers in the same market, we included only Metropolitan Statistical Areas with at least four freestanding nursing homes in both years, to permit meaningful ranking of facilities and standardization of nursing home performance measures across facilities within each Metropolitan Statistical Area (detailed below and in the appendix).20

When all of these data criteria were applied, our final analytic sample included 40,762 Hispanic residents and 504,953 non-Hispanic white residents (both as of 2005) living in 5,179 freestanding nursing homes located in 136 Metropolitan Statistical Areas. The 5,179 nursing homes were in operation in both 2000 and 2005, thus providing a “stable” sample that avoids certain sources of error (see appendix).20 This sample of nursing homes constitutes 35 percent of all certified freestanding nursing homes in the United States as of 2005. The residents of these facilities accounted for about 42 percent of all nursing home residents in freestanding facilities, and the 40,762 Hispanic nursing home residents included in our sample captured 84 percent of all Hispanic nursing home residents in 2005. Our sample of 136 Metropolitan Statistical Areas is distributed across the West (37 percent), South (35 percent), Northeast (17 percent), and Midwest (11 percent).

Measures We present measures of (1) ethnicity-specific nursing home use rates, (2) nursing home racial/ethnic segregation, and (3) ethnic disparities in nursing home performance in both 2000 and 2005. We report use rates and segregation measures for the nation as a whole and for the 136 selected Metropolitan Statistical Areas, and we present nursing home performance data on quality for the 5,179 nursing homes, comparing changes over the five-year period.

Nursing Home Use

We defined the age-adjusted use rate as the number of nursing home residents per 1,000 elderly population age sixty-five and older, separately for Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites in each year (using census data to calculate denominators).

Nursing Home Hispanic Segregation

We constructed two measures of the ethnic distribution of residents across nursing homes. The first characterizes ethnic composition at the facility level as the percentage of Hispanic residents, using three categories: no Hispanic residents (0 percent); some Hispanics but less than 15 percent; and 15 percent or more Hispanics (total facility denominators include all residents). The second indicator measures the extent of ethnic segregation at the Metropolitan Statistical Area level, using what is known as the Dissimilarity Index. This index compares the distribution of two population groups within a given geographic area; it is the most commonly used measure of segregation.21 It represents the combined percentage of nursing home residents of both groups (non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics) that would need to be relocated for there to be the same proportion of Hispanic and non-Hispanic white residents in every nursing home in a Metropolitan Statistical Area. A Dissimilarity Index of 1.00 would mean that there is no overlap of the two groups in facilities and that patients are totally segregated.

Nursing Home Performance Indicators

The performance indicators we used were derived from facility-level information from the Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting database. We constructed nine measures from this file: three related to deficiency citations, three to staffing levels, and three to the financial viability of the home. We made adjustments for state and regional variations that are described in the appendix.20 The nine performance indicators are organized under three categories, as follows.

Inspection deficiencies: Included in this category were the following measures: total number of scope-severity weighted deficiencies (standardized; see appendix for more details on the weights);20 whether the nursing home was deficiency-free; and whether the home was restraint-free.

Staffing: This category included the following: total direct care staffing hours per resident day (standardized); ratio of registered nurses (RNs) to total nurses (standardized); and nursing homes that were substantially understaffed as determined by an indicator developed by authors.22

Financial viability: Three financial measures (all standardized) included the following: the percentage of private-pay residents; occupancy rate; and percentage of Medicaid residents. Financial viability is usually higher where the percentage of private-pay residents is high, the occupancy rate is high, and the percentage of Medicaid residents is low.

Results

Hispanics' Use of Nursing Homes As has been reported elsewhere,18 nursing home use rates overall have been declining since 1985. At the same time, however, the racial/ethnic composition of the national population of nursing home residents has begun to shift. In just five years (2000–05) there was a decline in the percentage of nursing home residents who were non-Hispanic whites (from 82.7 percent to 79.4 percent), and a slight increase in the percentage who were black or Hispanic. The percentage of Hispanic residents increased by 1.4 percentage points, from 5.0 percent in 2000 to 6.4 percent in 2005, nationally; the percentage of black residents increased by 1.2 percentage points, from 10.0 percent to 11.2 percent.

The average nursing home use rate declined for both non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics over age sixty-five (age-standardized), with a slightly larger decline noted for elderly Hispanics (Exhibit 1). However, among the ten Metropolitan Statistical Areas with the largest Hispanic populations, there were four communities (three in Texas and one in California) in which the use rate among elderly Hispanics grew and another two (Miami, Florida, and Corpus Christi, Texas) in which the decline in nursing home use was less than one per 1,000 elderly people. Thus, declining nursing home use rates among Hispanic communities was not consistently observed for the group age sixty-five and older. Declining use rates for the oldest old (age eighty-five-plus) were more consistent.18

Exhibit 1. Age-Standardized U.S. Nursing Home Use Rate In Ten MSAs With Highest Proportions Of Hispanic Population, 2000 And 2005.

| Percent Hispanic population | Nursing home use rates, 2000 | Nursing home use rates, 2005 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| 2000 | 2005 | White | Hispanic | H/W Ratio | White | Hispanic | H/W Ratio | |

| National | 12.5% | 14.4% | 45.3% | 27.8% | 0.61 | 43.1% | 26.3% | 0.61 |

| Mean (across 136 MSAs) | 19.2 | 21.2 | 43.0 | 32.2 | 0.77 | 40.0 | 26.5 | 0.68 |

| 10 MSAs with highest % Hispanic pop in 2005: | ||||||||

| McAllen-Edinburg-Mission, TX MSA | 88.3 | 89.4 | 18.6 | 34.9 | 1.87 | 18.4 | 39.1 | 2.13 |

| Brownsville-Harlingen–San Benito, TX MSA | 84.3 | 86.0 | 30.0 | 30.5 | 1.01 | 26.6 | 34.4 | 1.29 |

| El Paso, TX MSA | 78.2 | 81.2 | 25.5 | 23.4 | 0.92 | 19.4 | 19.3 | 1 |

| Las Cruces, NM MSA | 63.4 | 64.8 | 27.2 | 21.2 | 0.78 | 27.4 | 15.6 | 0.57 |

| Miami, FL PMSA; Miami–Fort Lauderdale, FL CMSA | 57.3 | 60.6 | 35.5 | 23.6 | 0.66 | 30.6 | 23.1 | 0.75 |

| Corpus Christi, TX MSA | 54.7 | 57.2 | 44.1 | 46.3 | 1.05 | 38.9 | 45.8 | 1.18 |

| Visalia-Tulare-Porterville, CA MSA | 50.8 | 55.2 | 43.7 | 26.0 | 0.6 | 37.4 | 23.0 | 0.61 |

| San Antonio, TX MSA | 51.2 | 53.2 | 37.9 | 33.1 | 0.88 | 34.7 | 35.5 | 1.02 |

| Merced, CA MSA | 45.3 | 51.4 | 35.8 | 15.5 | 0.43 | 37.6 | 21.6 | 0.57 |

| Salinas, CA MSA | 46.8 | 50.8 | 68.6 | 36.9 | 0.54 | 53.9 | 31.9 | 0.59 |

Sources Nursing home resident assessment instrument Minimum Data Set, 2000 and 2005; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000 census and 2005 population estimates.

Notes Residents per 1,000 population age sixty-five and older. H/W is Hispanic/white. MSA is Metropolitan Statistical Area. PMSA is Primary MSA. CMSA is Consolidated MSA.

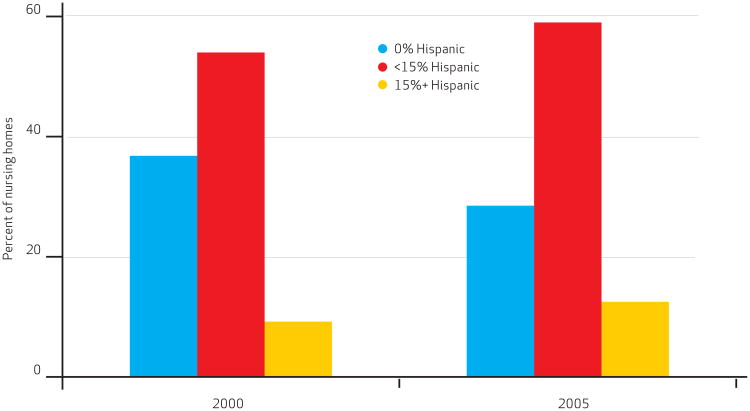

Hispanic Segregation Exhibit 2 displays the distribution of nursing homes by the proportion of Hispanic residents. It is based on data from 5,179 nursing homes that were in operation throughout 2000–05, located in Metropolitan Statistical Areas where at least 5 percent of the general population was Hispanic. The percentage of these nursing homes with no Hispanic residents declined substantially, from almost 37 percent to 28 percent, and the percentage of homes with some Hispanic residents and with more than 15 percent Hispanic residents grew. This suggests that the distribution of elderly Hispanics across nursing homes in these 136 Metropolitan Statistical Areas has begun to “equalize.” There were fewer homes with no Hispanic residents in 2005 compared to 2000 within these Metropolitan Statistical Areas.

Exhibit 2. Distribution Of U.S. Nursing Homes, By Percentage Of Hispanic Residents, 2000 And 2005.

Source Nursing home resident assessment instrument Minimum Data Set, 2000 and 2005. Note N = 5,179.

In other analyses (available from the authors upon request), we compared the segregation of black and Hispanic elderly residents of nursing homes to determine whether both groups are concentrated in the same facilities. In fact, Hispanics tend to use different nursing homes than blacks use; there is little overlap (based on data on 2005 nursing homes) in the highest categories of residence for these two groups, and the correlation between the percentage of Hispanics and the percentage of blacks in the same home is virtually nil (Rho = 0:02, p < 0:15).

Distributional issues are directly addressed by the Hispanic-white Dissimilarity Index for both 2000 and 2005. The index is reported for all nursing homes nationally, as well as separately for not-for-profit and for-profit homes. Since 2000, the Dissimilarity Index nationally declined somewhat, from 0.648 to 0.628. Similar small declines in segregation were seen in both nonprofit and for-profit nursing homes.

However, nonprofit homes continue to be more segregated than for-profit homes. Among this sample of 136 Metropolitan Statistical Areas, the five most segregated areas in terms of Hispanic/white nursing home residents as of 2005 were Lafayette, Indiana (0.92); Clarksville-Hopkinsville, Tennessee-Kentucky (0.91); Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers, Arkansas (0.90); Athens, Georgia (0.86); and Medford-Ashland, Oregon (0.73). The five least segregated were Reno, Nevada (0.08); Yuba City, California (0.10); Yolo, California (0.13); Richland-Kennewick-Pasco, Washington (0.16); and Pueblo, Colorado (0.17).

Disparities in Nursing Home Performance

Nursing Home Deficiencies

Three measures of nursing home inspection deficiencies were examined for 2000 and 2005, for three categories of nursing homes: those with no Hispanic residents, those with more than 0 percent but less than 15 percent Hispanic residents, and those with 15 percent or more Hispanic residents. In Exhibit 3, the standardized score of scope-severity weighted deficiencies for these three categories of nursing homes shows statistically significant differences: All-white nursing homes had significantly lower Metropolitan Statistical Area-averaged deficiency scores (signaling higher performance) than either category of nursing homes with Hispanic residents. Similarly, the percentage of homes that were deficiency-free was highest among all-white nursing homes in both years (note the declining percentages of deficiency-free homes over time). Finally, the percentage of homes that were “restraintfree” (no use of physical restraints, an indicator of higher-quality care) was twice as high for all-white homes, compared to either category of nursing homes with Hispanic residents. All of these differences were statistically significant (p < 0:001).

Exhibit 3. U.S. Nursing Home Performance, By Percentage Of Hispanic Residents, 2000 And 2005.

| Percent Hispanics, 2000 | Percent Hispanics, 2005 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 0% | <15% | ≥15% | 0% | <15% | ≥15% | |

| Inspection deficiencies | ||||||

| S-S weighted deficiency score (standardized) | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.05**** | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.06**** |

| Deficiency-free | 7.4% | 5.0% | 2.1%**** | 4.3% | 2.0% | 1.2%**** |

| Restraint-free | 20.3% | 10.6% | 10.5%**** | 28.9% | 16.3% | 13.0%**** |

| Staffing | ||||||

| Total direct care staffing HPRD (standardized) | 0.11 | −0.08 | −0.10**** | 0.08 | −0.08 | −0.12**** |

| RN/nurse ratio (standardized) | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.14**** | 0.12 | −0.07 | −0.08**** |

| Substantially understaffed | 15.1% | 15.9% | 16.5% | 14.6% | 16.7% | 17.0% |

| Financial viability | ||||||

| Percent private-pay (standardized) | 0.30 | −0.10 | −0.41**** | 0.30 | −0.11 | −0.40**** |

| Occupancy rate (standardized) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Percent Medicaid (standardized) | −0.29 | 0.09 | 0.43**** | −0.25 | 0.10 | 0.42**** |

| No. of nursing homes | 1,905 | 2,796 | 478 | 1,475 | 3,056 | 648 |

Sources Nursing home resident assessment instrument Minimum Data Set, 2000 and 2005; Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting (OSCAR) database, 2000 and 2005.

Notes N = 5,179. Statistical significance denotes between-group differences (one-way ANOVA). S-S is scope-severity. HPRD is hours per resident day. RN is registered nurse.

p < 0:001

Staffing Levels

Exhibit 3 also summarizes results for three indicators of staffing levels associated with differences in nursing home care quality. The standardized score for total direct care staffing was significantly higher for all-white homes compared to either category of nursing homes with Hispanic residents, as was the standardized ratio of registered nurses to total nurses. All-white homes tend to have higher levels of direct care staffing and have higher ratios of registered nurses to all nurses. The third indicator of staffing levels focused on the percentage of homes that are substantially understaffed. Although the percentage of homes that fall into this category tended to be higher among nursing homes with Hispanic residents (both categories), the differences (compared to all-white homes) were not statistically significant.

Financial Viability

The final category of nursing home performance, financial viability, is also shown in Exhibit 3. Standardized measures of percentage private-pay (associated with higher nursing home performance) were again highest for all-white homes and were substantially lower for both categories of homes with Hispanic residents. These measures were stable over the 2000–05 time period.

Occupancy rates were not statistically different across the three categories of homes and were fairly stable over time. The percentage of nursing home residents who were Medicaid-supported (associated with lower nursing home performance) was substantially higher for both categories of homes with Hispanic residents, and these numbers were stable over time. In 2005 the percentage of Medicaid-supported residents in nursing homes with more than 15 percent Hispanic residents was 30 percent higher than in homes with fewer Hispanic residents and more than 60 percent higher than in all-white homes.

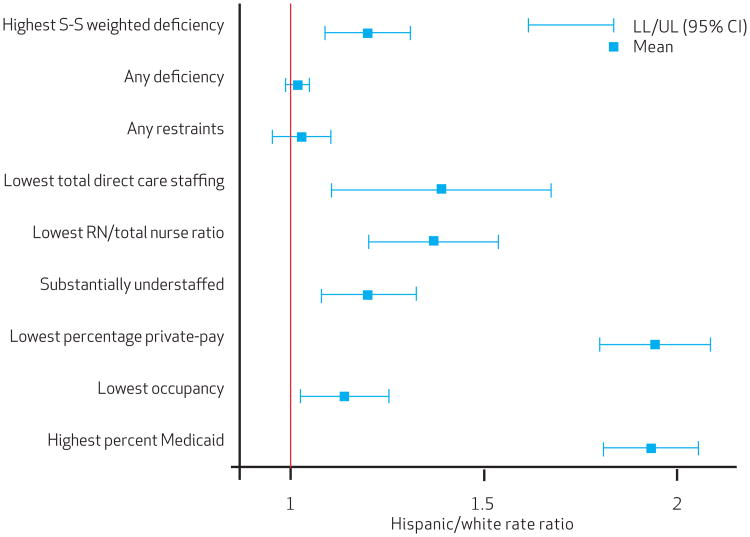

Disparities in Access to Poor-Performing Nursing Homes Exhibit 4 presents disparities at the level of the Metropolitan Statistical Area in access to poor-performing nursing homes for 2005 (results for 2000 were similar, but not shown here). These were measured using each of the nine nursing home performance indicators to compute a ratio of Hispanic compared to white nursing home residents and a 95 percent confidence interval. (Additional information on the ratios is available in the appendix.)20

Exhibit 4. Hispanics' Likelihood Of Residing In Poor-Performing U.S. Nursing Homes.

Sources Nursing home resident assessment instrument Minimum Data Set (MDS), 2000 and 2005; Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting (OSCAR) database, 2000 and 2005. Notes N = 136. Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs). S-S is scope-severity. RN is registered nurse. LL/UL is lower limit/upper limit. CI is confidence interval.

The results show that at the market level, elderly Hispanics are much more likely than elderly whites to reside in poor-performing facilities, and this holds true across nearly all nursing home performance indicators.23

Discussion

These descriptive results on nursing home use during 2000–05 by elderly Hispanics, and on the relative likelihood of residing in poorly performing nursing homes, reveal three clear findings.

First, the numbers of elderly Hispanics residing in nursing homes has been growing and will continue to grow. Although nursing home use rates overall have declined recently among non-Hispanic whites, there is considerable geographic variability in use rates among Hispanics. In Metropolitan Statistical Areas in the Southwest with large proportions of Hispanic residents, nursing home use rates by elderly Hispanics are often higher than those of whites (Exhibit 1). Nationally, the percentage of nursing homes with no Hispanic residents has declined significantly.

Second, elderly Hispanics are more likely than their non-Hispanic white peers to reside in nursing homes of poor quality. This result is consistent across three different constructs of nursing home quality: inspection deficiencies, staffing, and financial viability.

The findings are consistent at the level of both the nursing home and the Metropolitan Statistical Area. There are differences in nursing home performance levels by the percentage of nursing home residents who are Hispanic. As the percentage of Hispanic residents increases, nursing homes are more likely to be characterized by more severe deficiencies in performance, less likely to be deficiency or restraint-free, more likely to be understaffed, and more likely to be heavily dependent upon Medicaid funding. At the Metropolitan Statistical Area level, we can see that Hispanics are more likely to experience poor care, precisely because they are served by poor-quality facilities. These differences were consistent across the 2000–05 time period.

Third, these descriptive results suggest that perhaps the “buffering” effect of Hispanic family culture and values is weakening. Although the desire to keep Hispanic elders out of formal long-term care settings maybe very strong, the reality of the economic situation facing many Hispanic families may be overwhelming, particularly given rising rates of adult Hispanic women in the labor market and the rising cost of nursing home alternatives.

Unexplored Questions Our exploratory analyses did not allow us to address a number of important questions. For example, there may be differences in patterns of unequal access to high-quality nursing homes across different Hispanic groups, such as Mexican Americans compared to Cuban Americans or Puerto Rican Americans. Because these different subgroups are often geographically distinct, it is difficult to determine what is influencing observed patterns: ethnicity or geography.

The initial choice of nursing home placement following an acute care event or hospitalization is constrained by both hospital and nursing home bed availability. However, the “decision” at ninety days post acute (that is, to transform into a long-stay) could be constrained by a completely different set of family choices and long-term care market issues. In addition, the date at which Hispanic elders migrated to the United States may affect eligibility for both Medicare and Medicaid funding, complicating the choice set for Hispanic families even more.

Finally, migration patterns vary across different Hispanic groups, in terms of both historical timing of migration waves and age at time of migration. For example, elderly Cuban immigrants are more likely to be longer-term U.S. residents, compared to elderly Mexican immigrants; this might provide an advantage to elderly Cuban Americans' access to higher-quality nursing home care.24

Another set of factors not addressed in this analysis concerns the confounding of nursing home care quality with access to resources, either patient-related or nursing home-related. Our measures of the percentage of private-pay patients and the percentage of Medicaid patients are an indirect assessment of levels of nursing home resources that have been consistently tied to differences in nursing home care quality.3,4 The more dependent a nursing home is on Medicaid as a source of revenue, the less likely it is to have access to other resources that can help improve care quality.3

Thus, the pattern of “lower-tier” facilities emerges where underresourced facilities care for disproportionate numbers of patients who are both poor and from minority groups. Elderly Hispanics are less likely to be insured and more likely to be frail, disabled, or in poor health, compared to all other elderly subpopulations. As larger numbers of elderly Hispanics move into lower-tier facilities (for lack of personal resources needed for nursing home alternatives), the clustering of high-need acuity levels, inadequate staffing, and higher rates of inspection deficiencies combine into a relentless downward spiral. Lower-tier facilities are more likely to be terminated from the Medicaid and Medicare programs and are at greater risk of closure.

Possible Policy Interventions Others have discussed possible policy interventions that range from allowing poor-quality nursing homes to fail, increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates, and various efforts to build quality improvement efforts within troubled homes.25,26 There is no straightforward resolution to this issue, and any single proposal could run the risk of putting poor minority elders at even greater risk of inadequate care or displacement, or might encounter enormous political backlash.

The pattern of “lowertier” facilities emerges where under resourced faxcilities care for disproportionate numbers of patients who are both poor and from minority groups.

More resources must be part of the “fix,” but not the only part, and those additional resources must be focused on the homes that are most at risk. Policy proposals are needed that target at-risk nursing homes with multiple innovative solutions, including perhaps changes in management or “receivership” strategies, and the use of local volunteers and community oversight.

For elderly Hispanics, the prospect of a stay of any length in a nursing home is traumatic and isolating, given cultural and linguistic gaps. For them to be relegated to the bottom tier of care alternatives is a disparity that must be addressed.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented as a poster at the AcademyHealth Annual esearch Meeting, June 2008, in Washington, D.C. This research is supported by Grant no.1P01AG027296-01A1 from the National Institute on Aging.

Contributor Information

Mary L. Fennell, Email: Mary_Fennell@brown.edu, Professor of sociology and community health at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Zhanlian Feng, Assistant professor of community health (research) at Brown University.

Melissa A. Clark, Associate professor of community health at Brown University

Vincent Mor, Chair of the Department of Community Health at Brown University.

Notes

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Guidance for the national healthcare disparities report. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville (MD): AHRQ; 2002. Oct, National healthcare disparities report: fact sheet AHRQ Pub 03-P007. [cited 2009 Dec 4] Available from http://www.ahrq.gov/news/nhdrfact.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Q. 2004;82(2):227–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn JS, Mor V. Separate and unequal: racial segregation and disparities in quality across U.S. nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(5):1448–58. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn J, Mor V. Racial disparities in access to long-term care: the illusive pursuit of equity. J Health Polit Polic. 2008;33(5):861–81. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2008-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reed SC, Andes S. Supply and segregation of nursing home beds in Chicago communities. Ethn Health. 2001;6(1):35–40. doi: 10.1080/13557850124941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaugler JE, Kane RL, Kane RA, Newcomer R. Predictors of institutionalization in Latinos with dementia. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2006;21(3–4):139–55. doi: 10.1007/s10823-006-9029-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerardo MP, Teno JM, Mor V. Not so black and white: nursing home concentration of Hispanics associated with prevalence of pressure ulcers. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(2):127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.John R, Resendiz R, De Vargas LW. Beyond familism? Familism as explicit motive for eldercare among Mexican American caregivers. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1997;12(2):145–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1006505805093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Census Bureau [Internet] Washington (DC): U.S. Census Bureau; 2008. May, p. c2008.Press release, U.S. Hispanic population surpasses 45 million now 15 percent of total; [cited 2009 Dec 4] Available from: http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/population/011910.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angel R, Angel J. Who will care for us? Aging and long-term care on multicultural America. New York (NY): University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angel JL, Angel RJ, McClellan JL, Markides KS. Nativity, declining health, and preferences in living arrangements among elderly Mexican Americans: implications for long-term care. Gerontologist. 1996;36(4):464–73. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.4.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angel JL, Angel RJ. Minority group status and healthful aging: social structure still matters. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1152–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.085530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angel J, Hogan D. Population aging and diversity in a new era. In: Whitfield K, editor. Closing the gap: improving the health of minority elders in the new millennium. Washington (DC): Gerontological Society of America; 2004. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindstrom DP. Economic opportunity in Mexico and return migration from the United States. Demography. 1996;33(3):357–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace SP, Lewting CY. Getting by at home—community-based long-term care of Latino elders. W J Med. 1992;157(3):337–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Census Bureau. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2005 [Internet] Washington (DC): U.S. Census Bureau; 2006. Aug, [cited 2009 Dec 4] Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/p60-231.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alecxih L. Nursing home use by oldest old sharply declines [Internet] Fairfax (VA): Lewin Group; 2006. Nov 21, [cited 2009 Dec 4] Available from: http://www.adrc-tae.org/documents/NHTrends.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng Z, Katz PR. Physician and nurse staffing in nursing homes: the role and limitations of the Online Survey Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) system. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The online appendix is available at http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/29/1/hlthaff.2009.0003/DC1

- 21.Iceland J, Weinberg DH, Steinmetz E. Racial and ethnic residential segregation in the United States:1980–2000. Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; 2002 May 9-11; Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The authors' understaffing indicator characterizes facilities whose average nursing case-mix index score was above the Metropolitan Statistical Area median but whose total direct care staffing hours per resident day were at least two quartiles below their quartile ranking on nursing case-mix index.

- 23.Two of the nine rate ratios (regarding the citation of deficiencies and use of restraints) were not statistically significant but were in the same direction.

- 24.Angel JL, Buckley CJ, Sakamoto A. Duration or disadvantage? Exploring nativity, ethnicity, and health in midlife. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(5):S275–84. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.5.s275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser Family Foundation. Nursing home quality: state agency survey funding and performance. Washington (DC): Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukamel DB, Spector WD. Quality report cards and nursing home quality. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):58. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]