Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid beta (Aβ) protein and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Various studies suggest that the tau tangle pathology, which lies downstream to Aβ pathology, is essential to produce AD-associated clinical phenotype and thus treatments targeting tau pathology may prevent or delay disease progression effectively. In this context, our present study examined three polyphenol compounds (curcumin, EGCG and resveratrol) for their possible activity against two endogenous proteins (BAG2 and LAMP1) that are shown to play a vital role in clearing tau tangles from neurons. Human epidemiological and animal data suggest potential positive effects of these polyphenols against AD. Here, primary rat cortical neurons treated with these polyphenols significantly up-regulated BAG2 levels at different concentrations, while only EGCG upregulated LAMP1 levels, although at higher concentrations. Importantly, curcumin doubled BAG2 levels at low micromolar concentrations that are clinically relevant. In addition, curcumin also downregulated levels of phosphorylated tau, which may be potentially attributed to the curcumin-induced upregulation in BAG2 levels in the neurons. The present results demonstrate novel activity of polyphenol curcumin in up-regulating an anti-tau cochaperone BAG2 and thus, suggest probable benefit of curcumin against AD-associated tauopathy.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, tau, polyphenol, curcumin, BAG2

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, pathologically characterized by extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) [19]. The NFTs consist of paired helical filaments of microtubule-associated tau protein that is hyperphosphorylated [15] and the density of tau tangles correlates well with regional and global aspects of AD-associated cognitive dysfunction [1]. Furthermore, the established toxic role of tau in certain genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia [24] strongly suggests that tau aggregation may result in a toxic gain-of-function leading to the AD-associated neurodegeneration. Thus, there is a growing interest in discovering novel compounds that will help in reducing the deleterious accumulation of tau protein tangles in the AD brain.

Epidemiological studies suggest an inverse correlation between dietary polyphenol consumption and the incidence of AD. The polyphenols of particular therapeutic importance are curcumin, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and resveratrol, which have been suggested to have the potential to prevent AD pathology owing to their anti-amyloidogenic, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory properties [13]. The consumption of curcumin, the principal curcuminoid of the spice turmeric extensively used in Indian culinary, is suggested to be responsible for the low age-adjusted prevalence of AD in India [27]. Numerous studies also indicate green tea consumption may decrease incidence of AD and EGCG is the main component of green tea [28]. Furthermore, resveratrol is a polyphenolic compound found in grapes and red wine, and is suggested to be responsible for the observed inverse relationship between wine consumption and incidence of AD [20].

The anti-amyloid properties of these polyphenol compounds are well studied and suggested to be underlying their preventive effects against AD pathology. Curcumin has been shown to decrease Aβ deposition and Aβ oligomerization in in vivo studies [11]. Furthermore, curcumin and EGCG have been shown to suppress Aβ-induced beta-site APP cleaving enzyme-1 (BACE1) upregulation, thus breaking the vicious cycle of Aβ pathogenesis [23]. EGCG has also been shown to increase non-amyloidogenic processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP) through the α-secretase ADAM10 [8]. Furthermore, resveratrol has been shown to activate AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and in turn lead to the autophagy-dependent degradation of Aβ peptides [26]. In terms of potential anti-tau activities of these polyphenols, curcumin and related polyphenols have been shown to inhibit aggregation of tau [9]. Also, EGCG has been shown to modulate tau profiles in transgenic AD models [22]. Finally, resveratrol has been shown to reduce hippocampal neurodegeneration in the animal and cell-based models of AD and tauopathies, possibly through activating SIRT1 deacetylase [12]. Despite these data, the underlying molecular mechanisms by which these polyphenol compounds may protect against AD-associated tau pathology are not well understood.

Therefore, our present study focused on the possible role of these polyphenols in upregulating two potential endogenous regulators of tau viz. BCL2-Associated Athanogene 2 (BAG2) and Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 1 (LAMP1) [3,4]. Primary cortical neurons were isolated from one-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups and cultured as described by Chandler et al. [5]. The experiments were performed on 3–4 day old culture. The cells were treated with the polyphenol compounds at different doses for 24 h.

To determine the cell toxicity in neuronal cells, the secreted and intracellular levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were measured by using a cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche, IN). The cytotoxicity was determined as a percentage, i.e. the fraction of LDH released into the medium (LDHmedium), relative to the total LDH (LDHmedium and LDHintracellular):

For western blot analysis, cells were washed three times with ice-cold TBS (25 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, and 5 mM KCl) and lysed for 20 minutes by scraping into ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer [21]. Equal amounts of total protein from each condition were run at 200 V on 10% SDS-PAGE gels (BioRad, CA) for BAG2, LAMP1, total tau, phosphorylated tau and actin. The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 1 hour at 100 V and incubated at 4°C overnight with the appropriate primary antibodies [1:1000 BAG2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), 1:1000 LAMP1 (Abcam, MA), 1:200 PHF-1 (from Dr. P. Davies, Albert Einstein, NY), 1:200 AT8 (Pierce Biotechnology, IL), 1:1000 Tau5 (Calbiochem, CA), 1:2000 actin (Sigma, MO)]. Appropriate HRP-linked secondary antibodies (Pierce Biotechnology, IL) were used to detect the primary antibodies.

For miRNA analysis, the total miRNAs were then extracted with the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, CA) and RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen), and subsequently quantified using the ND-1000 NanoDrop spectrophotometer. RNA quality control was performed by assessing OD 260/280 ratio. Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted, following reverse transcription of the miRNAs (miR-128 and miR-9) using miScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), with miScript SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) and MyiQ real time PCR detection system according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All miRNA primers were purchased from Qiagen and the relative expressions were calculated by the comparative CT method using RNU6B as the normalizing control. The mature miRNA sequence for primer designing were 5′UCACAGUGAACCGGUCUCUUU3′ and 5′ UCUUUGGUUAUCUAGCUGUAUGA3′ for miR-128 and miR-9, respectively. The reverse transcribed miRNA was used at 3 ng for qRT-PCR with denaturing at 94°C, annealing at 55°C and extension at 70°C for 40 cycles. Additionally, melting curves (at 80 cycles with 0.5°C increments) were produce to validate the specificity of the reactions.

To examine the potential polyphenol-induced upregulation of BAG2 and LAMP1 levels, primary rat cortical neurons were treated with various doses of these compounds for 24 h. Curcumin significantly affected cell viability at 50 μM concentration (Fig. 1). In accordance with this, curcumin significantly affected cell morphology at 50 μM and caused complete cell death at 100 μM (data not shown). EGCG increased extracellular LDH release at 50 and 100 μM (Fig. 1), but had no apparent effect on cell morphology at these concentrations (data not shown). On the other hand, resveratrol at all concentrations had no effect on both cell viability (Fig. 1) and morphology (data not shown). Based on these data, the highest concentration of curcumin used in the present study was 25 μM, while that for EGCG and resveratrol was 100 μM. After 24 h treatment, cells were lysed and western blot analysis was performed to determine cellular levels of BAG2 and LAMP1 proteins. All three polyphenols significantly increased BAG2 levels in neurons, although at different concentrations (Figs. 2–4); EGCG and resveratrol were effective only at the highest concentration tested (Figs. 3 and 4), while curcumin dose-dependently and significantly increased BAG2 protein levels in primary rat cortical neurons at low micromolar concentrations that are clinically relevant (Fig. 2). Furthermore, EGCG also increased LAMP1 levels dose-dependently and significantly (Fig. 3). Here, it is noteworthy that both BAG2 and LAMP1 proteins have been suggested to be beneficial against AD-associated tau pathology [3,4]. The BAG2/Hsp70 complex is tethered to the microtubule and has been shown to be involved in regulating paired helical filament tau levels in neurons [4]. Also, LAMP1 is a major glycoprotein constituting up to 50% of total protein in the lysosomal membrane [6] and its expression has been shown to be increased in NFT-free neurons in AD brain, while decreased in NFT-bearing neurons [3], suggesting a possible role of LAMP1 in NFT turnover in AD brains. The potential role of lysosomes and possibly LAMP proteins in mitigating tau pathology is further emphasized by a recent study, whereby inhibition of lysosomal proteolysis in neurons caused Alzheimer-like axonal dystrophy [16]. These studies, together with our present data, may suggest that the observed polyphenol-induced upregulation in BAG2 and LAMP1 levels may lead to the clearance of the pathological tau inclusions from the neurons. Here, we studied the possible effects of our polyphenols on the total and phosphorylated tau levels in primary rat cortical neurons, through immunoblotting with Tau5, AT8 and PHF-1 antibodies. Tau5 antibody detects total tau levels, while AT8 and PHF-1 antibodies recognize tau protein hyperphosphorylated at AD-specific phospho-epitopes [21]. Our data showed that none of these polyphenols had any effect on the basal levels of total as well as phosphorylated tau in the cortical neurons (data not shown). This is in accordance with previously published study, whereby one of our three polyphenols, EGCG, has been shown to have no effect on total phosphorylated tau levels, while only affecting sarkosyl-soluble tau levels in transgenic AD mice [22]. Furthermore, the observed, EGCG-induced downregulation in sarksoyl-soluble tau in transgenic AD mice did not go below the basal level observed in normal mice [22], thus further emphasizing lack of effect of polyphenol EGCG on the basal levels of tau.

Figure 1.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. Treatment for 24 h with 50 μM curcumin and 50 μM or higher EGCG caused increased LDH release from neurons as compared with controls. In contrast, resveratrol at all concentrations had no effect on LDH release. Data are taken from three different experiments and are expressed as mean ± SD.

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent effect of curcumin on BAG2 levels in neurons. Immunoblots show significant up-regulation of BAG2 in a dose-dependent manner, while LAMP1 remained unaffected. Histogram represents quantitative determinations of intensities of the relevant bands of BAG2 normalized to actin. Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments (Student’s t test- *, p < 0.05 compared with control).

Figure 4.

Effect of resveratrol on BAG2 in neurons. Immunoblots show significant up-regulation of BAG2 at 100 μM, while LAMP1 remained unaffected. Histogram data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments (Student’s t test- *, p < 0.05 compared with control).

Figure 3.

Effect of EGCG on BAG2 and LAMP1 in neurons. Immunoblots show significant up-regulation of BAG2 at 100 μM, while LAMP1 increased in a dose-dependent manner. Histograms represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments (Student’s t test- *, p < 0.05 compared with respective control).

Due to this observed lack of polyphenols on basal tau levels, we decided to study if polyphenols, especially curcumin at clinically relevant concentration (12.5 μM) has any effect on tau levels under pathologically hyperphosphorylated conditions. For this, we found that incubating primary rat cortical neurons with okadaic acid (OA) induced the abnormally phosphorylated AT8 epitope in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A), thereby providing a cellular model to investigate the pathological phospho-tau epitope. Similar OA-induced cellular taupathy models have been reported previously [7,25]. By using this model with 10 nM OA, we explored the potential effects of curcumin on the tau phosphorylation and found that treatment with 12.5 μM curcumin efficiently countered the OA-induced elevation in the levels of phosphorylated tau (Fig. 5B). Given this, together with the our novel finding that curcumin at 12.5 μM also doubled the levels of anti-tau BAG2 protein, may suggest a possible role of curcumin-induced BAG2 expression in the observed decrease in phospho-tau levels in these neurons. The direct link between curcumin-induced BAG2 upregulation and PHF1 downregulation, however, is unclear and requires further investigation.

Figure 5.

(A) The okadaic acid (OA)-induced pathological hyperphosphorylation of tau in neurons. The AT8 immunoblot shows significant up-regulation in phospho-tau levels in a dose-dependent manner. (B) Inhibition of OA-induced tau hyperphosphorylation by curcumin. Primary rat cortical neurons were treated with 10 nM OA for 24 h, followed by 12.5 μM curcumin for 24 h (post-treatment) or preceded by 12.5 μM curcumin for 24 h (pre-treatment) or together with 12.5 μM curcumin (co-treatment). The AT8 immunoblot shows curcumin efficiently countered OA-induced tau hyperphosphorylation. Histogram data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments (Student’s t test- *, p < 0.05 compared with control).

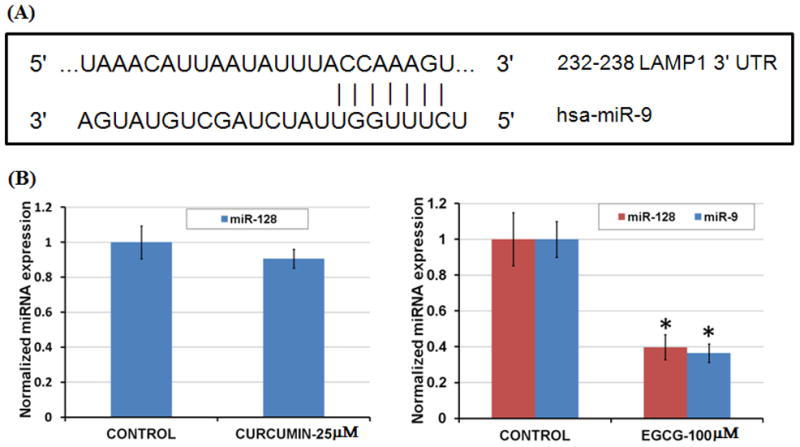

Finally, the underlying mechanism of how these polyphenols upregulate BAG2 and LAMP1 protein levels in neurons is unclear at present. Previously, BAG2 levels in COS-7 cells have been shown to be regulated by the microRNA miR-128a [4]. Thus, it is possible that our polyphenols may be affecting miR-128a levels, thus in turn leading to the observed upregulation in BAG2 levels in neurons. Furthermore, the microRNA miR-9, is predicted by TargetScan and PicTar to target the LAMP1 3′ untranslated region (LAMP1 3′UTR) with a 7 nt complementarity in the seed region (Fig. 6A) [10,14]. Thus, the observed EGCG-induced upregulation in LAMP1 levels in neurons may be through its effect on miR-9 levels. Here, it is interesting to note that of all the microRNAs expressed in adult brain, only miR-9 and miR-128 have been shown to be significantly elevated in AD brains as compared to the age-matched controls [17]. Specifically, miR-9 was found to be upregulated in both fetal and AD hippocampus, while miR-128 was increased specifically in AD hippocampus [2]. Furthermore, dysregulation of metal ion homeostasis has been suggested to play a vital role in AD pathogenesis and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-producing metal sulfates, iron- and aluminum-sulfates, have been shown to significantly elevate miR-128 and miR-9 levels in primary human neural cells [18]. Thus, anti-oxidative polyphenols may have modulatory effects on the pathological elevation of AD-associated miRNAs viz, miR-128 and miR-9, leading in turn to the upregulation of BAG2 and LAMP1 levels, respectively. Our preliminary data showed that EGCG significantly downregulated levels of both miR-128 and miR-9 (Fig. 6B), although at higher concentration (100 μM) that is not physiologically relevant. Furthermore, curcumin also had limited effect on the level of miR-128 at both 12.5 μM and 25 μM (Fig. 6B). Thus, the exact molecular mechanism underlying the observed, polyphenol-induced BAG2 and LAMP1 upregulation is unclear at present and warrants further investigation.

Figure 6.

(A) The microRNA miR-9 predicted target site on LAMP1 3′UTR. (B) The microRNA analysis. The quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) study showed significant down-regulation of both miR-128 and miR-9 levels in EGCG-treated cells, while curcumin had no significant effect on miR-128 levels. Relative expressions shown are normalized to RNU6B and average control (n=9) expressions (*, p < 0.05 compared with control).

In summary, our present study suggests probable benefit of the use of polyphenol curcumin against AD-associated tau pathology, possibly through upregulating levels of cochaperone BAG2 protein that has been shown previously to clear tau tangles from neurons.

Highlights.

We studied effects of curcumin, EGCG and resveratrol on BAG2 and LAMP1 levels.

All three compounds upregulated BAG2 levels at different concentrations.

EGCG also upregulated LAMP1 levels dose-dependently.

Curcumin downregulated phosphorylated tau levels in a cellular phosho-tau model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, NY) for kindly providing PHF-1 antibody and Rebecca Martin for isolating the primary cells. This work was funded in part by the National Science Foundation (CBET 0941055), the National Institutes of Health (R01GM079688 and R01GM089866) and the Office of the VP for research and Graduate Studies.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid beta

- EGCG

(−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate

- BAG2

BCL2-associated athanogene 2

- LAMP1

Lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1

- NFTs

neurofibillary tangles

- BACE1

beta-site APP cleaving enzyme-1

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- ADAM10

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 10

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- OA

okadaic acid

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arriagada PV, Growdon JH, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Neurofibrillary tangles but not senile plaques parallel duration and severity of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1992;42(3 Pt 1):631–639. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbato C, Ruberti F, Cogoni C. Searching for MIND: microRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;(2009):871313. doi: 10.1155/2009/871313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrachina M, Maes T, Buesa C, Ferrer I. Lysosome-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP-1) in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2006;32(5):505–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2006.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrettiero DC, Hernandez I, Neveu P, Papagiannakopoulos T, Kosik KS. The cochaperone BAG2 sweeps paired helical filament- insoluble tau from the microtubule. J Neurosci. 2009;29(7):2151–2161. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4660-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandler LJ, Newsom H, Sumners C, Crews F. Chronic ethanol exposure potentiates NMDA excitotoxicity in cerebral cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 1993;60(4):1578–1581. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang MH, Hua CT, Isaac EL, Litjens T, Hodge G, Karageorgos LE, Meikle PJ. Transthyretin interacts with the lysosome-associated membrane protein (LAMP-1) in circulation. Biochem J. 2004;382(Pt 2):481–489. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Z, Chen B, Xu WF, Liu RF, Yang J, Yu CX. Effects of PTEN inhibition on regulation of tau phosphorylation in an okadaic acid-induced neurodegeneration model. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2012;30(6):411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez JW, Rezai-Zadeh K, Obregon D, Tan J. EGCG functions through estrogen receptor-mediated activation of ADAM10 in the promotion of non-amyloidogenic processing of APP. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(19):4259–4267. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Why pleiotropic interventions are needed for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41(2–3):392–409. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27(1):91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamaguchi T, Ono K, Yamada M. REVIEW: Curcumin and Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):285–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim D, Nguyen MD, Dobbin MM, Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Rodgers JT, Delalle I, Baur JA, Sui G, Armour SM, Puigserver P, Sinclair DA, Tsai LH. SIRT1 deacetylase protects against neurodegeneration in models for Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EMBO J. 2007;26(13):3169–3179. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J, Lee HJ, Lee KW. Naturally occurring phytochemicals for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2010;112(6):1415–1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, MacMenamin P, da Piedade I, Gunsalus KC, Stoffel M, Rajewsky N. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37(5):495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee MS, Kwon YT, Li M, Peng J, Friedlander RM, Tsai LH. Neurotoxicity induces cleavage of p35 to p25 by calpain. Nature. 2000;405(6784):360–364. doi: 10.1038/35012636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Sato Y, Nixon RA. Lysosomal Proteolysis Inhibition Selectively Disrupts Axonal Transport of Degradative Organelles and Causes an Alzheimer’s-Like Axonal Dystrophy. J Neurosci. 2011;31(21):7817–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6412-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukiw WJ. Micro-RNA speciation in fetal, adult and Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Neuroreport. 2007;18(3):297–300. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280148e8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukiw WJ, Pogue AI. Induction of specific micro RNA (miRNA) species by ROS-generating metal sulfates in primary human brain cells. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101(9):1265–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattson MP. Pathways towards and away from Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2004;430(7000):631–639. doi: 10.1038/nature02621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orgogozo JM, Dartigues JF, Lafont S, Letenneur L, Commenges D, Salamon R, Renaud S, Breteler MB. Wine consumption and dementia in the elderly: a prospective community study in the Bordeaux area. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1997;153(3):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patil S, Chan C. Palmitic and stearic fatty acids induce Alzheimer-like hyperphosphorylation of tau in primary rat cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2005;384(3):288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rezai-Zadeh K, Arendash GW, Hou H, Fernandez F, Jensen M, Runfeldt M, Shytle RD, Tan J. Green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) reduces beta-amyloid mediated cognitive impairment and modulates tau pathology in Alzheimer transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2008;1214:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shimmyo Y, Kihara T, Akaike A, Niidome T, Sugimoto H. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and curcumin suppress amyloid beta-induced beta-site APP cleaving enzyme-1 upregulation. Neuroreport. 2008;19(13):1329–1333. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32830b8ae1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spillantini MG, Bird TD, Ghetti B. Frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: a new group of tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 1998;8(2):387–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vandermeeren M, Lubke U, Six J, Cras P. The phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid induces a phosphorylated paired helical filament tau epitope in human LA-N-5 neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci Lett. 1993;153(1):57–60. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90076-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vingtdeux V, Chandakkar P, Zhao H, d’Abramo C, Davies P, Marambaud P. Novel synthetic small-molecule activators of AMPK as enhancers of autophagy and amyloid-beta peptide degradation. FASEB J. 2011;25(1):219–231. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-167361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang HM, Zhao YX, Zhang S, Liu GD, Kang WY, Tang HD, Ding JQ, Chen SD. PPARgamma agonist curcumin reduces the amyloid-beta-stimulated inflammatory responses in primary astrocytes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(4):1189–1199. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-091336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinreb O, Amit T, Mandel S, Youdim MB. Neuroprotective molecular mechanisms of (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate: a reflective outcome of its antioxidant, iron chelating and neuritogenic properties. Genes Nutr. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s12263-009-0143-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]