Abstract

Crack/cocaine and engagement in risky sexual behvaior represent important contributors to the escalation of the HIV infection among women. Several lines of research have emphasized the role of social factors in women’s vulnerability for such practices and stressed the importance of understanding such factors to better inform prevention efforts and improve their effectivenes and efficiency. However, few studies have attempted to pinpoint specific social/contextual factors particularly relevant to high risk populations such as female crack/cocaine users. Extensive previous research has related the experience of social rejection to a variety of negative outcomes including, but not limited to, various forms of psychopathology, self-defeating and self-harm behvaior. Motivated by this research, the current study explored the role of laboratory induced social rejection in moderating the relationship between gender and risky sexual behvaior among a sample of crack/cocaine users (n = 211) at high risk for HIV. The results showed that among women, but not among men, experiencing social rejection was significantly associated with a greater number of sexual partners. Further, experiencing social rejection was not related to the frequency of condom use. Implications for future research, prevention, and treatment are discussed.

Risky sexual behavior (RSB) continues to be the leading cause of HIV infection worldwide. Heterosexual contact is the only mode of HIV transmission that has continued to be on the rise since 1985 (CDC, 2011). This is particularly the case among high-risk substance using populations, most commonly non-injection crack/cocaine users (CDC, 2007; Kuo et al., 2011). The recent trend in the HIV/AIDS epidemic has placed women at particularly high risk for new infection (CDC, 2011) due to elevated rates of crack/cocaine use (Bornovalova, Lejuez, Daughters, Rosenthal, & Lynch, 2005; Lejuez, Bornovalova, Reynolds, Daughters, & Curtin, 2007) and corresponding higher rates of RSB, including multiple casual sex partners, exchange of sex for money or drugs, and inconsistent use of condoms (Chiasson, Stoneburner, Hildebrandt, & Ewing, 1991; Cohen et al., 1994; Edlin et al., 1994; Inciardi, 1995; Joe & Simpson, 1995; Weatherby, Shultz, Chitwood, & McCoy 1992). The importance of the association between crack/cocaine use and risky sexual behavior in increasing women’s vulnerability for new HIV infection justifies the need for new research to identify gender-specific risk factors associated with RSB within this population.

In trying to understand such factors, researchers have often emphasized the pharmacological effects of cocaine. From this perspective, cocaine use was believed to contribute to increased likelihood of engaging in RSB by increasing arousal, desire, stamina, performance, and/or enjoyment, as well as impulsivity (Lejuez, Bornovalova, Daughters, & Curtin, 2005; Pfaus et al., 2009; Rawson, Washton, Domier, & Reiber,, 2002; Volkow, et al., 2007). However, this perspective has recently been challenged by several studies that revealed the deleterious effects of chronic cocaine use on sexual behavior (Brown, Domier, & Rawson, 2005; Kopetz, Reynolds, Hart, Kruglanski, & Lejuez, 2010). Specifically, these studies showed that chronic cocaine use is often associated not only with diminished sexual desire, but also with difficulty in maintaining an erection, delayed ejaculation, and/or difficulty in achieving orgasm (Kopetz et al., 2010). Furthermore, the pharmacological effects of cocaine are not known to affect men and women differentially and could not explain women’s particular vulnerability to increased rates of RSB. The controversies regarding the direct effects of cocaine on sexual behavior suggest the possibility that other factors may contribute to female crack/cocaine users’ vulnerability to RSB and therefore to HIV infection.

One possibility suggested by both human and animal behavior research refers to the broader social and cultural context in which crack/cocaine is obtained and used (Amaro, 1995; El-Bassel, Gilbert, & Rajah, 2003; Kopetz et al., 2010; Leigh, 1990; Leigh & Stall, 1993; Pfaus, 2009; Stall & Leigh, 1994). This research has emphasized the importance of considering the contextual variables (i.e., expectations, social norms) that drive the behavior of men and women and the interpersonal relationships wherein sexual behavior occurs when trying to understand the relationship between the use of crack/cocaine and RSB (Amaro, 1995; Baseman, Ross, & Williams, 1999; Baumeister & Vohs, 2004; Ehrhardt & Wasserheit, 1991; Kopetz et al., 2010; Leigh, 1990; Ross, Hwang, Zack, Bull, & Williams, 2002; Tortu et al., 1998).

Early initiation of drug use, high frequency of use (Hoffman, Klein, Eber, & Crosby, 2000; Lejuez et al., 2007; Logan, Cole, & Leukefeld, 2003), childhood emotional and physical abuse (Bornovalova, Gwadz, Kahler, Aklin, & Lejuez, 2008; Bornovalova, Daughters, & Lejuez, 2010), high rates of violent intimate relationships, involvement in the criminal justice system, and initiation of sexual activity at an earlier age (Logan & Leukefeld, 2000; Logan et al., 2003) are often associated with crack/cocaine use among low income female users. Such social and economic adversities contrast sharply with socially prescribed female gender role of communion, intimacy, and interdependence (Cross & Madson, 1997; Eagly, 1987; Eagly & Wood, 1999; Eagly, Wood, & Diekman, 2000; Mahalik et al., 2005; Wood, Christensen, Helb, & Rothgerber, 1997) and may be particularly relevant to the social context surrounding RSB. To the extent that conforming to social norms and behaving in a way that is socially accepted and approved ensures social inclusion and satisfies one’s need for belongingness, failing to attain such social standards may increase one’s feelings of alienation and stigmatization and his/her sensitivity to social rejection (Romero-Canyas, Downey, Pelayo, & Bashan, 2004), thereby having important consequences for risk taking.

Indeed, the need to belong has been recognized as one of the most basic and pervasive human motivations (Buss, 1990; Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Baumeister, 2012; Maslow, 1968). Consequently, perceiving oneself as socially rejected has been associated with devastating consequences for psychological well-being including but not limited to low self-esteem and self-concept, experience of loneliness, guilt, worthlessness, depression, anxiety (Leary, 1990; Stillman et al., 2009), higher incidence of psychopathology (Bloom, White, & Asher, 1979; Williams, 2001), reduced immune system functioning (Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Bernston, 2003), and antisocial responses such as aggressiveness (e.g. Romero-Canyas, Downey, Berenson, Ayduk, & Kang, 2010; Twenge, Baumeister, Tice, & Stucke, 2001; Catanese & Tice, 2005), as well as self-defeating and self-destructive behavior (e.g. Twenge, Catanese, & Baumeister, 2003).

Particularly relevant for the current study is the association between social rejection and behavior that may increases personal risk. Indeed, fear of rejection has been associated with lower-levels of self-reported decision-making power in participants’ sexual relationships, and less consistent HIV prevention efforts (Paprocki, Downey, Berenson, Bhushan, El-Bassel, 2008). Women tend to be particularly vulnerable to problematic intimate relationships and risk taking in association with social rejection. High fear of rejection among women is more often associated with romantic breakups (Downey, Freitas, Michaelis, & Khouri, 1998). Furthermore, among socially and economically disadvantaged adolescent girls, participants’ fear of rejection (rejection sensitivity) predicted insecurity about boyfriends’ commitment (Purdie & Downey, 2000), suppression of one’s opinions (Ayduk, May, Downey, & Higgins, 2003) and willingness to do things that contravene one’s values in the hope of preserving a relationship (Purdie & Downey, 2000).

Current Study

In light of these findings, the current study aims to explore the potential role of social rejection as an important risk factor for engagement in RSB among women crack/cocaine users. We argue that social and economic factors (e.g. unemployment, history of abuse, etc.) found to be associated RSB among women crack/cocaine users indicate a failure to attain the societal sex-typed normative standards and may increase women’s sensitivity to social rejection which in turn represents a risk factor for engagement in RSB.

To test these notions we recruited 211 primary crack/cocaine users from a low-income, high risk area of Washington, D.C. We assessed perceived social rejection following a laboratory procedure specifically designed to induce the experience of social rejection (Williams & Jarvis, 2006) and tested the relationship between gender and self-reported RSB (number of sexual partners in the last year as well as frequency of condom use) as well as the degree to which perceived social rejection moderated this relationship. We hypothesized that among women, heightened experience of social rejection would be related to higher rates of risky sexual behavior. Furthermore, we expected perceived social rejection to be unrelated to male RSB.

Method

Participants and Setting

Participants were recruited from a residential substance use treatment facility in an area of Washington D.C. at high-risk for HIV/AIDS over a period of several years. Upon entry into the facility, all patients were administered a structured interview assessing sociodemographic variables, Axis I and II psychopathology (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV), as well as the history and pattern of drug use. We assessed frequency of substance use through a standard drug use questionnaire modeled after the Drug History Questionnaire (DHQ; Sobell, Kwan, & Sobell, 1995) targeting past 12 months use. Response options were: 0 (never), 1 (one time), 2 (monthly or less), 3 (2–4 times a month), 4 (2–3 times a week), and 5 (4 or more times a week). Individuals were recruited to participate in the current study if they 1) reported using crack/cocaine two to four times a month at any point in the past twelve months, 2) had no current symptoms of psychosis, and 3) were in their 2nd to 7th day at the treatment facility (to ensure that withdrawal symptoms did not interfere with individuals’ ability to complete the study and to control for the effects of time in treatment).

We screened a total of 510 individuals, and of those, 211 met all inclusion criteria. In the recruited sample, 68% were males and 88% were African American, with a mean age of 45 (SD = 7.05). In terms of education level, 25% of the participants did not complete any high school education, 42% completed high school, and 33% had some college, technical/business education, or had graduated from college.

The substance abuse treatment facility requires complete abstinence from drugs and alcohol (including the prohibition of any form of agonist treatment such as methadone) with the exception of nicotine and caffeine; patients are tested weekly and any evidence of drug use during treatment is grounds for dismissal from the center. All patients are required to undergo full detoxification and be free of drugs at intake (thereby limiting the likelihood of extreme withdrawal effects during the study period). Patients enter the treatment center either voluntarily or under a pretrial-release-to-treatment program through the District of Columbia Pretrial Services Agency (53.3% of our participants). This program offers drug offenders who are awaiting trial the option to receive substance abuse treatment as a way to ensure appearance in court, provide community safety, and address an underlying cause of recidivism. Patients are contracted to a specific length of stay upon entry into the treatment center. For the current sample, contract lengths included 30 days (41.4%), 60 days (29.7%), 90 days (6.3%), or 180 days (22.6%).

Procedures and Measures

Patients who were eligible for the study based on the initial screening were invited to participate in a study examining factors related to risky drug use and sexual behavior. They were told that they would be compensated $25 in grocery store gift cards for their time. Interested participants were given a more detailed explanation of the procedure and asked to provide written informed consent. All participants underwent a single assessment session that took place during individuals’ free time at the treatment facility. All participants were assessed individually in a private room. They completed a procedure designed to induce social rejection, completed measures of experienced social rejection, and self-reported RSB as detailed below.

Risky sexual behavior (RSB)

Participants completed a modified version of the sexual behavior subscale of the HIV Risk-Behavior Scale (HRBS; Darke, Hall, Heather, Ward & Wodak, 1991). The scale is a self-report measure consisting of five items pertaining to the number of sexual partners as well as condom use. Two questions assessed the number of penetrative and oral sex partners. Specifically, participants were asked to report the number of partners (including regular, casual, and commercial partners) with whom they had had penetrative sex in the past twelve months. The same question was asked separately in regard to oral sex. Response options included: 0 (none), 1 (one), 2 (two), 3 (three to five), 4 (six to 10), and 5 (more than 10 people). Three additional questions assessed condom use separately for regular, casual, and commercial partners. Participants reported the number of times a condom was used when having sex with regular, casual, and commercial partners respectively on a scale where response options included 0 (no sexual partners), 1 (every time), 2 (often), 3 (sometimes), 4 (rarely) and 5 (never). To obtain participants’ score for the number of sexual partners, we added the corresponding scores reported on the two items regarding the number of partners with whom participants had penetrative and oral sex in the last year (Darke et al., 1991). Similarly, the score for condom use was obtained by adding the scores corresponding to the three items assessing frequency of condom use with regular, casual, and commercial partners respectively. The questionnaire is designed such that higher scores represent higher risk for HIV infection through sexual behavior.

Induction of social rejection

Participants completed a computerized behavioral task called Cyberball (Williams & Jarvis, 2006) designed to induce the experience of social rejection. The game is a virtual ball-toss game, and it is a widely used paradigm to study the effects of ostracism, social exclusion, or rejection (Williams, Cheung, & Choi, 2000; Williams, 2001; Williams et al., 2002). In this task, participants were led to believe that they were playing a ball toss online (the game has the appearance of an internet browser) with two other players. In actuality, the participants played alone. Participants were told they could throw the ball to whomever they wished and they believed that the other “players” could do so as well. After the task was explained, participants were allowed to familiarize themselves with the task by playing for a minute. The experience of social rejection is introduced after this familiarization phase. Specifically, participants received three throws at the beginning of the game, after which the other “players” stopped throwing to the participant. The program ended after 30 throws and the participant was prompted to continue with a questionnaire designed to assess the subjective experience of rejection.

Subjective experience of rejection

To assess participants’ subjective experience of rejection following the Cyberball game, they were asked to complete the Need-Threat Questionnaire (Williams et al., 2000; Jamieson, Harkins, & Williams, 2010; Williams, 2009). The questionnaire is a self-report measure consisting of 12 items assessing the extent to which participants experienced rejection as a result of playing the Cyberball game. Participants were presented with 12 statements (e.g., During the Cyberball “I felt disconnected,” “I felt rejected”) and asked to rate how much each statement applied to them on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Higher scores indicate stronger subjective experience of social rejection. The questionnaire had strong internal consistency (α = .87). We therefore averaged the responses to the 12 individual items into one score representing participants’ subjective experience of social rejection.

Following the completion of the study, participants were debriefed. The gift cards earned for participation in the study were mailed to them upon treatment termination to an address that they had provided when they consented to participate in the study.

Results

We conducted a preliminary analysis to test the effect of gender on socio-demographic variables and psychopathology relevant to our outcome. There were no significant gender differences on any relevant socio-demographic variable. Furthermore, substance use did not significantly vary as a function of gender. However, there were significant gender differences on several Axis I and II psychopathology. Specifically, compared to men, women were more frequently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) (20% vs. 36%, X2(1) = 5.61, p = .01), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (7% vs. 14%, X2(2) = 7.22, p = .02), and borderline personality disorder (BPD) (22% vs. 40%, X2(2) = 9.22, p = .01). By contrast, men were more frequently diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder than women (32% vs. 11%, X2(2) = 10.44, p < .01). However, there was no effect of psychopathology (ts < 1 for MDD, GAD, BPD, and APD), or of the interaction between gender and psychopathology (ts < 1) on the number of sexual partners or condom use. Therefore, psychopathology will not be included in any further analyses.

To test our hypothesis of interest we conducted two separate multiple regression analyses where the number of sexual partners and frequency of condom use respectively were regressed on experienced social rejection (centered), gender, and their product (representing the interaction term) (Aiken & West, 1991). The descriptive statistics for the number of partners, condom use, and experienced social rejection are presented separately for each gender in Table 1. Table 2 presents the zero-order correlations between the variables separately by gender.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the number of partners and experienced social rejection presented by gender3

Experienced Social Rejection;

Number of Sexual Partners;

Frequency of condom use across regular, casual, and commercial partners

Table 2.

Zero-order correlation matrix

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSP | FCU | ESR | NSP | FCU | ESR | |

| NSP | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| FCU | .64** | 1.00 | .48** | 1.00 | ||

| ESR | .09 | .06 | 1.00 | .28* | .02 | 1.00 |

p = .05;

p=.01

Number of sexual partners

Due to the fact that this type of measure is typically not normally distributed, we first assessed the skewedness of the data. Number of partners was only moderately skewed (.46) whereas condom use was positively skewed (.90). We therefore log transformed the data to normalize the distribution and ran the analysis on the transformed scores.

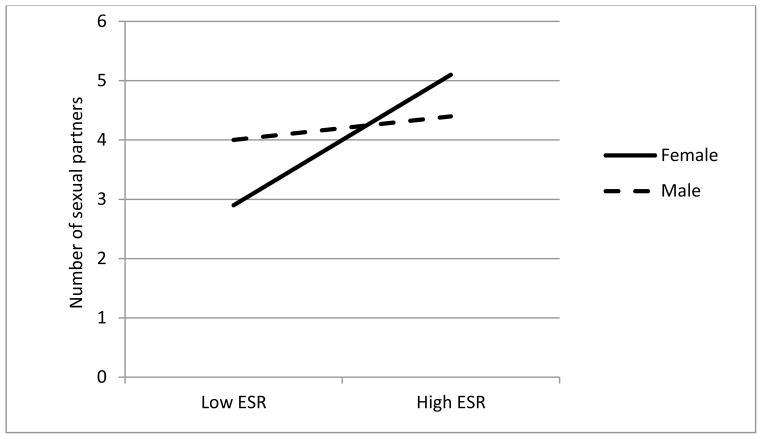

Regarding the number of sexual partners, the analysis revealed that the overall model including gender, experienced social rejection (centered), and their interaction term, significantly predicted the number of sexual partners (R2 = .03, F(3, 207) = 2.24, p < .05). The regression coefficients are presented in Table 3. There was no main effect of gender and experienced social rejection on the number of partners. However, a significant interaction between the two predictors emerged (B = .13, t(207) = 1.19, p < .05). To further examine this interaction, we conducted a simple slope analysis for each gender group. As depicted in Figure 1, for females, subjective experience of rejection was positively related to the number of sexual partners (B = .20, t(207) = 2.32, p < .05). By contrast, experienced social rejection was not significantly related to the number of sexual partners for males (B = .07, t(207) = 1.08, p = .27)1.

Table 3.

Number o f sexual partners as a function of gender, experienced social rejection, and their interaction (N = 211)

| B | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.16 | .21 | 5.37 | .00 |

| Gender | .46 | .36 | 1.27 | .20 |

| ESR | .07 | .06 | 1.08 | .27 |

| Gender X ESR | .13 | .11 | 1.19 | .04 |

R2 = .031, p < .05

Figure 1.

Predicted number of sexual partners4 as a function of gender and experienced social rejection. High and low values of experienced social rejection represent plus or minus one standard deviation from the variable mean.

Frequency of condom use

The second multiple regression analysis was conducted to predict participants’ self-reported frequency of condom use across regular, commercial, and casual partners. Specifically, frequency of condom use was regressed on gender, subjective experience of social rejection (centered) and their product (interaction term). Unlike in the case of number of partners, our model did not significantly predict frequency of condom use (R2 = .006, F(3, 207) = .42, p = .73)2. The regression coefficients are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Frequency of condom use as a function of gender, experienced social rejection, and their interaction (N = 211)

| B | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.29 | .21 | 5.94 | .00 |

| Gender | .10 | .36 | .29 | .76 |

| ESR | .04 | .06 | .66 | .50 |

| Gender X ESR | .00 | .11 | .05 | .95 |

R2 = .00, p = .73

Discussion and Implications

The current study represents an attempt to identify critical social/contextual factors that may be related to female crack/cocaine users’ vulnerability for engagement in RSB and therefore for HIV infection. Specifically, we explored the extent to which the subjective experience of social exclusion may represent a risk factor for engagement in RSB (number of sexual partners in the last year as well as frequency of condom use) among women.

The results showed that experiencing social rejection interacted with gender in predicting engagement in RSB among 211 crack/cocaine users in treatment. More specifically, experiencing social rejection following a laboratory ostracism paradigm predicted the number of self-reported sexual partners (both oral and penetrative sexual behavior) among women, but not among men. In other words, heightened subjective experience of social rejection was related to a higher number of sexual partners for female, but not for male crack/cocaine users. It is notable that our model (i.e. experienced social rejection, gender, and their interaction) was not related to condom use. Methodological as well as theoretical reasons may account for our failure to find a relationship between our predictors and condom use. Participants’ scores for condom use indicate very little variance in self-reported condom use suggesting that the frequency of condom use in this particular high risk sample may be generally very low. Our measure might have been insufficiently sensitive to capture individual variance which might have in turn contributed to our failure to find a significant relationship. On the other hand, at a conceptual level, risky sexual behavior is a very complex behavior that may encompass different dimensions and specific behaviors (i.e. number and type of sexual partners, condom use) which may or may not be present simultaneously and which may be facilitated by different factors. Due to the importance of communion and intimacy emphasized by female gender role, the experience of rejection seems particularly relevant for the number of partners with whom women may engage in sexual relationships, rather than for their use of condoms.

Although the cross-sectional nature of the current study limits our ability to draw a definitive conclusion about the nature of the relationships found, the results are notable as they replicate previous findings linking social exclusion to negative outcomes, particularly among socially disadvantaged women, and extend them to a problem of major public health concern. Indeed, previous research has observed antisocial responses to exclusion including increased aggressiveness (e.g. Twenge et al., 2001; Catanese & Tice, 2005), self-defeating and self-destructive behavior (Twenge et al., 2003), as well as less consistent HIV prevention efforts (Paprocki et al., 2008), and problematic intimate relationships Downey et al., 1998; Purdie & Downey, 2000)

One possible explanation for such findings comes from both field and laboratory studies showing that being sensitive to rejection and therefore more likely to experience rejection more negatively is related to impairments in executive functioning, self-control, and self-regulation (Baumeister, Twengem & Nuss, 2002; Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Twenge, 2005) and therefore to higher susceptibility to self-defeating and self-destructive behavior (Ayduk et al., 2008). It is thus possible that experiencing social rejection may impair individual’s ability for self-control and result in higher risk taking propensity which may in turn result in increased vulnerability for RSB in general.

Another possibility that may explain women’s vulnerability to RSB in relation to social rejection is suggested by the research showing that experiencing social exclusion motivates strategic behavior aimed at interpersonal reconnection. Indeed, the mere threat of social rejection has been found to result in more cooperation, (Ouwerekerk, van Lange, Gallucci, & Kerr, 2005), increased conformity as a means to improve one’s inclusionary status (Williams et al., 2002), a higher tendency to imitate others in order to be liked and accepted (Lakin & Chartrand, 2005), and increased willingness to do things that contravene one’s values in the hope of preserving a relationship (Purdie & Downey, 2000).

To the extent to which RSBs are not only expected, but also sought for in the context of cocaine use (Davey-Rothwell & Latkin, 2007; Kopetz et al., 2010; Rhodes, 1996), it is possible that fear and/or experience of social rejection may increase the women’s likelihood of engagement in such behavior as a means to attain the intimacy and communion prescribed by the gender roles and therefore to fulfill their need for belonging. Each of these possibilities should be explored more systematically in future research designed to allow causal conclusions regarding the association between social rejection and engagement in RSB and to understand the mechanisms underlying it.

Limitations, future directions, and implications

Our study represents a preliminary attempt to address a problem of high public concern, engagement in RSB in the context of drug use, from a theoretical perspective that allows us to identify critical factors that may enhance individuals’ vulnerability for such practices and to study them systematically. However, there are several limitations that must be acknowledged and addressed in future research. Probably the most important limitation refers to the cross-sectional nature of our study which hinders our ability to draw any conclusions about the causal relationship between social exclusion and engagement in risk taking. There are strong theoretical reasons and extensive empirical evidence suggesting that the extent to which individuals are vulnerable to and experience social rejection may increase the likelihood of engaging in RSB. However, future research should address this possibility in a manner that allows clear conclusions about the causality of this relationship and that offers insights into the mechanisms that may underlie it.

Another limitation is related to the assessment battery which relied exclusively on retrospective self-reports of sexual behavior. Although participants’ ability to accurately report their past sexual behaviors may be questionable, there is little reason to suspect that biases and inaccuracies in their self-report would systematically impact their reports in a manner that would threaten the internal validity of the current study. However, such biases and inaccuracies might have introduced substantial random error in our measure and might have therefore contributed to the small effect size observed. Future studies would therefor benefit greatly from using prospective designs or laboratory measures of risk taking to address such limitation.

Third, our sample consists to a large extent of drug users attending substance use treatment as a pre-trail requirement which may limit the generalizability of the study. Future research should attempt to replicate the current findings on a more heterogeneous sample of drug users.

Finally, there are some theoretical limitations that are worth of attention. Although there are strong theoretical and empirical reasons to believe that social rejection is related to one’s likelihood to engage in potentially harmful behaviors (such as RSB) there are also reasons to believe that this may not be the case across all individuals. It is possible that this relationship would be particularly strong among women who believe that they deviate from social norms, especially gender roles emphasizing intimacy and communion (Josephs et al., 1992; Wood et al., 1997) compared to women who do not hold such perceptions. Identifying individual vulnerabilities is therefore of great theoretical and practical public health relevance and should represent a priority in future research.

In closing, experts worldwide have noted the importance of considering RSB associated with cocaine use in the light of broader social variables that drive the behavior of men and women. However, there are very few attempts to address these issues from a theoretical perspective that would allow a systematic investigation of such variables and of the manner in which they increase individuals’ vulnerability for HIV risk behavior. This is unfortunate because our limited understanding of the specific mechanisms through which various distal factors affect individuals’ tendency to engage in such behaviors might be one reason why the impact of empirical research on HIV prevention programs has remained relatively limited, with much of the existing interventions failing to demonstrate HIV risk behavior change. The current study is small in scope but it takes a step forward and proposes a personality and social psychology perspective to identify critical social factors and to investigate their relation to individuals’ engagement in RSB in the context of cocaine use. The results suggest that experiencing social exclusion may be an important risk factor for such behavior and that women are particularly vulnerable. Furthermore, the current findings speak to the importance of incorporating enhancement of social support in prevention and treatment efforts for crack/cocaine abuse particularly for women. As this line of research moves forward with more sophisticated tools and in-depth batteries, it should provide important empirical support to inform the development of targeted prevention strategies to reduce HIV infection disparities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse grant R01DA19405 awarded to Carl W. Lejuez and F32DA026253 awarded to Catalina Kopetz

Footnotes

We also ran the analysis controlling for MDD, GAD, BPD, and APD, which showed significant gender effects to explore the possibility that they may reduce the residual effects. The model containing these variables did not significantly predict our variables of interest anymore, (F < 1). This is probably due to the fact that psychopathology was not related to the outcome. Furthermore, the effect of the interaction between gender and perceived social rejection on the number of partners remained significant in predicting the number of sexual partners (B = .14, t(179) = 1.63, p < .05), as did the simple effects for females (B = .19, t(179) = 1.98, p < .05), but not for male participants (B = .05, t(179) < 1).

The results remained unchanged when MDD, GAD, BPD, and APD were controlled for

There were 143 males and 68 females in our sample

For ease of interpretation, the figure displays the raw rather than the log-transformed data

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H. Love, sex, and power: Considering women’s realities in HIV prevention. American Psychologist. 1995;50:437–447. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.50.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk O, May D, Downey G, Higgins ET. Tactical differences in coping with rejection sensitivity: The role of prevention pride. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:435–448. doi: 10.1177/0146167202250911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayduk O, Zayas V, Downey G, Cole AB, Shoda Y, Mischel W. Rejection sensitivity and executive control: Joint predictors of borderline personality features. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:151–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseman J, Ross M, Williams M. Sale of sex for drugs and drugs for sex: An economic context of sexual risk behaviors for STDs. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26:444–449. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199909000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The Need to Belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF. Need-to-Belong Theory. In: Lange PMAV, Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET, editors. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Vol. 2. Sage Publications Ltd; 2012. pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Twenge JM. Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:589–604. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Twenge JM, Nuss CK. Effects of social exclusion on cognitive processes: Anticipated aloneness reduces intelligent thought. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:817–827. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD. Sexual economics: Sex as female resource for social exchange in heterosexual interactions. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2004;8:339–363. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0804_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BL, Asher SJ, White SW. Marital disruption as a stressor: A review and analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1978;85:867–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Gwadz MA, Kahler C, Aklin WM, Lejuez CW. Sensation seeking and risk-taking propensity as mediators in the relationship between childhood abuse and HIV-related risk behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB, Rosenthal MZ, Lynch TR. Impulsivity as a common process across borderline personality and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:790–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW. The function of sexual contact and high-risk sexual behavior across commercial, casual, and regular partners among urban drug users: Contextual features and clinical correlates. Behavior Modification. 2010;34:219–246. doi: 10.1177/0145445510364414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AH, Domier CP, Rawson RA. Stimulants, sex, and gender. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2005;12:169–180. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM. The evolution of anxiety and social exclusion. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Bernston GG. The anatomy of loneliness. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2003;12:71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Catanese KR, Tice DM. The effect or rejection on anti-social behaviors: Social exclusion produces aggressive behaviors. In: Williams KD, Forgas JP, von Hippel W, editors. The social outcast: Ostracism, social exclusion, rejection, and bullying. New York, NY US: Psychology Press; 2005. pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Cattell RB. What is structured learning theory? British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1996;66:411–413. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Drug-associated HIV transmission continues in the United States. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/idu.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV surveillance report: Diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/index.htm.

- Chiasson MA, Stoneburner RL, Hildebrandt DS, Ewing WE. Heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 associated with the use of smokable freebase cocaine (crack) AIDS. 1991;5:1121–1126. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Navaline H, Metzger DS. High-risk behaviors for HIV: A comparison between crack-abusing and opioid-abusing African-American women. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1994;26:233–241. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1994.10472436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J. The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk-taking behaviour among intravenous drug users. AIDS. 1991;5:181–185. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. HIV-related communication and perceived norms: An analysis of the connection among injection drug users. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007;19:298–309. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.4.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Freitas AL, Michaelis B, Khouri H. The self-fulfilling prophecy in close relationships: Rejection sensitivity and rejection by romantic partners. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75:545–560. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.2.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Wood W. The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. In: Travis CB, editor. Evolution, gender, and rape. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1999. pp. 265–304. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Wood W, Diekman AB. Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: A current appraisal. In: Eckes T, Trautner HM, editors. The developmental social psychology of gender. Mahwah NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 123–174. [Google Scholar]

- Edlin BR, Irwin KL, Faruque S, McCoy CB. Intersecting epidemics: Crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;331:1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt AA, Wasserheit JN. Age, gender, and sexual risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. In: Wasserheit JN, Aral SO, Holmes KK, Hitchcock PJ, editors. Research issues in human behavior and sexually transmitted diseases in the AIDS era. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1991. pp. 97–121. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Rajah V. The relationship between drug abuse and sexual performance among women on methadone. Heightening the risk of sexual intimate violence and HIV. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1385–1403. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JA, Klein H, Eber M, Crosby H. Frequency and intensity of crack use as predictors of women’s involvement in HIV-related sexual risk behaviors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;58:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA. Crack, crack house sex, and HIV risk. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1995;24:249–269. doi: 10.1007/BF01541599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson JP, Harkins SG, Williams KD. Need threat can motivate performance after ostracism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:690–702. doi: 10.1177/0146167209358882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Simpson DD. HIV risks, gender, and cocaine use among opiate users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1995;37:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)01030-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs RA, Markus HR, Tafarodi RW. Gender and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:391–402. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopetz CE, Reynolds EK, Hart CL, Kruglanski AW, Lejuez CW. Social context and perceived effects of drugs on sexual behavior among individuals who use both heroin and cocaine. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2010;18:214–220. doi: 10.1037/a0019635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo I, Greenberg AE, Magnus M, Phillips G, Rawls A, Peterson J, et al. High prevalence of substance use among heterosexuals living in communities with high rates of AIDS and poverty in Washington, DC. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;117:139–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakin JL, Chartrand TL. Exclusion and nonconscious behavioral mimicry. In: Williams KD, Forgas JP, von Hippel W, editors. The social outcast: Ostracism, social exclusion, rejection, and bullying. New York, NY US: Psychology Press; 2005. pp. 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1990;9:221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC. The relationship of substance use during sex to high-risk sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research. 1990;27:199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and RSB for exposure to HIV: Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Daughters SB, Curtin JJ. Differences in impulsivity and sexual risk behavior among inner-city crack/cocaine users and heroin users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Bornovalova MA, Reynolds EK, Daughters SB, Curtin JJ. Risk factors in the relationship between gender and crack/cocaine. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:165–175. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Leukefeld C. HIV risk behavior among bisexual and heterosexual drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:239–248. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Gender differences in the context of sex exchange among individuals with a history of crack use. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2003;15:448–464. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.6.448.24041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslow AH. Toward a psychology of being. 2. Oxford England: D. Van Nostrand; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ouwerkerk JW, van Lange PAM, Gallucci M, Kerr NL. Avoiding the social death penalty: ostracism and cooperation in social dilemmas. In: Williams KD, Forgas JP, von Hippel W, editors. The Social Outcast: Ostracism, Social Exclusion, Rejection, and Bullying. The Psychology Press; New York: 2005. pp. 539–558. [Google Scholar]

- Paprocki C, Downey G, Berenson K, Bhushan D, El-Bassel N. Rejection sensitivity, high-risk relationships, and women’s health. Paper presented at the International Association for Relationship Research; Providence, RI. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus JG. Pathways of sexual desire. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6:1506–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaus JG, Wilkins MF, DiPietro N, Benibgui M, Toledano R, Rowe A, Couch M. Inhibitory and disinhibitory effects of psychomotor stimulants and depressants on the sexual behavior of male and female rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2010;58:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdie V, Downey G. Rejection sensitivity and adolescent girls’ vulnerability to relationship-centered difficulties. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:338–349. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Washton A, Domier CP, Reiber C. Drugs and sexual effects: Role of drug type and gender. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(01)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T. Culture, drugs and unsafe sex: Confusion about causation. Addiction. 1996;91:753–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1996.tb03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Canyas R, Downey G, Berenson K, Ayduk O, Kang NJ. Rejection sensitivity and the rejection-hostility link in romantic relationships. Journal of Personality. 2010;78:119–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Canyas R, Downey G, Pelayo R, Bashan U. The threat of rejection triggers social accommodation in rejection sensitive men. Poster presented at the Fifth Annual Meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology; Austin, TX. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ross MW, Hwang LY, Zack C, Bull L, Williams ML. Sexual risk behaviours and STIs in drug abuse treatment populations whose drug of choice is crack cocaine. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2002;13:769–774. doi: 10.1258/095646202320753736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Kwan E, Sobell MB. Reliability of a drug history questionnaire (DHQ) Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:233–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)00071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stall R, Leigh B. Understanding the relationship between drug and alcohol use and risk sexual activity for HIV transmission: Where do we go from here. Addiction. 1994;89:131–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stillman TF, Baumeister RF, Lambert NM, Crescioni AW, DeWall CN, Fincham FD. Alone and without purpose: Life loses meaning following social exclusion. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;45:686–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortu S, Goldstein M, Deren S, Beardsley M, Hamid R, Ziek K. Urban crack users: Gender differences in drug use, HIV risk, and health status. Women & Health. 1998;27:177–89. doi: 10.1300/J013v27n01_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Baumeister RF, Tice DM, Stucke TS. If you can’t join them, beat them: Effects of social exclusion on aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81:1058–1069. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.6.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Catanese KR, Baumeister RF. Social Exclusion and the Deconstructed State: Time Perception, Meaninglessness, Lethargy, Lack of Emotion, and Self-Awareness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:409–423. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Telang F, Jayne M, Wong C. Stimulant-induced enhanced sexual desire as a potential contributing factor in HIV transmission. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:157–160. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherby NL, Shultz JM, Chitwood DD, McCoy HV. Crack cocaine use and sexual activity in Miami, Florida. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24:373–380. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism: The power of silence. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior Research Methods. 2006;38:174–180. doi: 10.3758/bf03192765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Cheung CKT, Choi W. Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:748–762. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Govan CL, Croker V, Tynan D, Cruickshank M, Lam A. Investigations into differences between social and cyberostracism. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2002;6:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD. Ostracism: Effects of being excluded and ignored. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2009;41:279–314. [Google Scholar]

- Wood W, Christensen P, Hebl MR, Rothgerber H. Conformity to sex-typed norms, affect, and the self-concept. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology. 1997;73:523–535. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]