Abstract

Background

Clinical trials with passive and active AD vaccines suggest that early interventions are needed for improvement of cognitive and/or functional performance in patients providing impetus for the development of safe and immunologically potent active vaccines targeting amyloid β (Aβ). The AN-1792 trial has indicated that Aβ-specific T cells may be unsafe for humans; therefore, other vaccines based on small Aβ epitopes are undergoing pre-clinical and clinical testing.

Methods

Humoral and cellular immune responses elicited in response to a novel DNA epitope-based vaccine (AV-1955) delivered to rhesus macaques using the TriGrid electroporation device were evaluated. Functional activities of anti-Aβ antibodies generated in response to vaccination were assessed in vitro.

Results

AV-1955 generates long-term, potent anti-Aβ antibodies and cellular immune responses specific to foreign T helper (Th) epitopes, but not to self-Aβ.

Conclusion

This translational study demonstrates that a DNA-based epitope vaccine for AD could be appropriate for human clinical testing.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Translational, Epitope vaccine, Rhesus macaques, Antibody response, Cellular immune response, DNA vaccine, Electroporation, Amyloid β

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized clinically by progressive cognitive decline, eventually resulting in death, usually within 10 years of diagnosis. It is estimated that there are currently more than 18 million people worldwide with AD and the number of affected individuals is projected to double by 2025. A critical aim in developing therapeutic interventions for AD has been the identification of suitable targets. Currently, the predominant theory of the etiology of AD is that a 40–43 amino acid peptide, amyloid β (Aβ), has a central role in the onset and progression of the disease, as described in the amyloid cascade hypothesis[1]. According to this hypothesis, the accumulation of Aβ peptide either by overproduction or aberrant clearance, results in the deposition of Aβ in plaques. This promotes the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and cell death, resulting in dementia. In recent years, the amyloid cascade hypothesis has evolved to focus on oligomers and protofibrils of Aβ as instigators in the destruction of synaptic function[2]. Discovery of rare genetic mutations associated with early-onset AD [3] offers the strongest evidence to date that excess Aβ is a causative factor in AD, bolstering hopes that anti-amyloid treatments may be feasible.

Many strategies for the development of therapies for AD are aimed at reducing the level of Aβ in the brain and/or blocking assembly of the peptide into pathological forms that disrupt cognitive function[4, 5]. Based on the intriguing finding that a vaccine containing fibrillar Aβ42 prevented the deposition of Aβ in a transgenic mouse model of AD[6], a number of animal studies have since demonstrated that immunotherapies targeting Aβ can inhibit its deposition in plaques and reduce behavioral deficits. These immunotherapies include vaccines consisting of Aβ-based immunogens or passive administration of Aβ-specific antibodies[7]. Unfortunately, thus far, efforts to translate immunotherapeutic strategies that were successful in animal models to AD patients have been largely unsuccessful. Notably, a Phase IIa trial evaluating AN-1792, a vaccine containing full length fibrillar Aβ42, was halted prematurely when a subset of the immunized individuals developed meningoencephalitis, likely due to autoreactive T cell responses to self-epitopes within the Aβ42 peptide[8]. This finding indicated that active vaccination approaches need to avoid harmful anti-Aβ specific T cell responses. Fortuitously, subsequent studies demonstrated that B and T helper (Th) cell antigenic determinants of Aβ42 are localized in different regions of the peptide [9] and antibodies specific to the N-terminal region of Aβ42 significantly reduced amyloid burden in APP transgenic mice[10–12].

Based on data described above, we proposed an epitope vaccine strategy [13] and designed various peptide- and DNA-based epitope vaccines with the goal of generating potent antibody responses specific to Aβ and reducing the risk of inducing autoreactive Th cells[9]. The preventive and therapeutic efficacy and immunogenicity of these vaccines, which were composed of a short self immunodominant B cell epitope of Aβ42 (Aβ11) and the non-self universal Th cell epitope, PADRE, has been demonstrated in wild-type and APP transgenic mice[14–17]. In the previous studies we used a strong adjuvant/s for peptide/protein vaccines or delivery with the gene-gun (GG) for DNA vaccines to induce potent immune responses. More recently, to enhance plasmid transfection efficacy and generate strong immune responses we performed electroporation (EP)-mediated delivery of our DNA epitope vaccine for AD in mice [17] using an intramuscular delivery system (TDS-IM) (reviewed in [18] and Evans and Hannaman, in press) and demonstrated that EP is as effective as the GG[17].

In this study we refined our vaccine candidate with the goal of designing a safe DNA epitope vaccine that, when delivered by EP in target populations at risk for development of AD, will induce strong and therapeutically potent immune responses. Accordingly, in addition to the Th epitope PADRE, we included multiple known human Th cell epitopes from several pathogens [tetanus toxin (TT): P2, P21, P23, P30 and P32; hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or nuclear capsid proteins (HBVnc), and influenza matrix protein (MT)] that most adults have either been exposed to or vaccinated against. In addition to providing broad coverage of human MHC polymorphism, we hypothesized this novel DNA vaccine (designated as AV-1955) may reactivate pathogen-specific pre-existing memory Th cells and thereby provide potent help to B cells producing Aβ-specific antibodies. Initial testing of AV-1955 delivered with electroporation in mice (unpublished data) indicated that mice generated robust Aβ-specific antibodies to the vaccine. As a step towards clinical testing in humans, studies of this vaccine were initiated in rhesus macaques. The goals were to determine whether this vaccine design could promote antibody responses to Aβ without generating Aβ-specific T cells; learn about the kinetics of the immune responses and frequency of additional booster vaccine administrations required to maintain Aβ-specific antibodies responses; as well as to evaluate overall safety of the vaccine in non-human primates (NHP). The data presented here demonstrate that in rhesus macaques, AV-1955 induces strong cellular immune responses specific to the portion of the vaccine encoding foreign Th epitopes, but not to Aβ. Importantly, these cellular immune responses provide support for production of IgG antibodies specific to the Aβ component of AV-1955.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Thirteen adult, male, genetically unselected rhesus macaques ranging in age from 2 years 8 months to 3 years 9 months from the primate colony at the New Iberia Research Center (New Iberia, LA) were utilized for this study. The macaques had not received any vaccines prior to this study, and they had not been used in any research studies. The macaques were housed in accordance with accepted standards and monitored daily for signs of illness or distress. Animals were randomized to study groups by body weight (ranging from 3.4 to 5.7 kg) prior to study initiation. Animals were observed once daily for abnormal clinical signs and/or signs of illness or distress, which included food intake, activity, appearance, and stool consistency. Body weights were measured prior to the first plasmid DNA administration and at the time of subsequent DNA administrations and blood draws.

2.2. DNA constructs

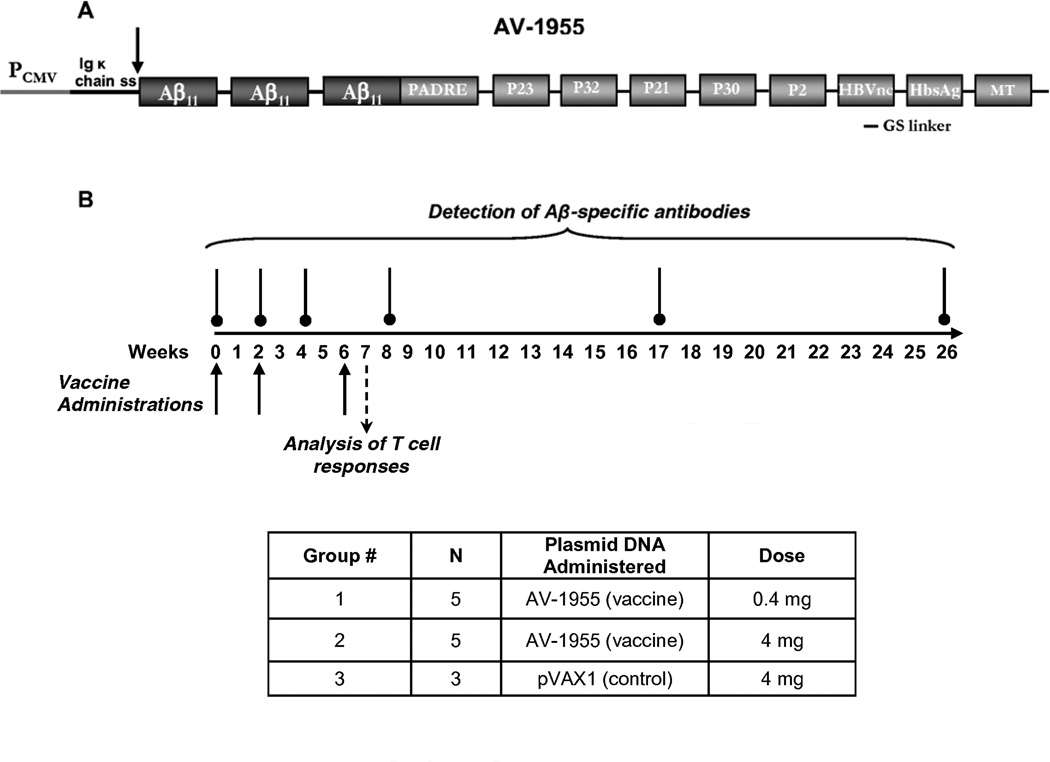

AV-1955 was generated by modification of the construct p3Aβ11-PADRE previously described in[19]. Briefly, the AV-1955 codes for a protein consisting of the Ig κ-chain signal sequence, three copies of the Aβ11 B cell epitope (of note, the Aβ42 sequence is identical in rhesus macaques and humans), one synthetic peptide (PADRE), and a string of eight non-self promiscuous Th epitopes (Thep) from TT (= P2, P21, P23, P30 and P32), hepatitis B virus (HBsAg, HBVnc ) and influenza (MT), that can bind to various human MHC class II proteins (Fig.1A)[20, 21]. The N-terminus of the fusion protein after cleavage of the signal sequence corresponds to the natural N-terminus of Aβ since evidence indicates that humans may generate strong antibody responses to the N-terminus of the Aβ epitope[22]. For generation of AV-1955, a polynucleotide encoding the Th epitopes separated by glycine-serine (GS) linkers was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ) and ligated with the 3Aβ11-PADRE minigene described previously[19]. The pVAX1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), which was designed to be consistent with current Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines, was used as the plasmid backbone. To prepare the recombinant proteins, minigenes encoding 3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep or PADRE-Thep were cloned into the modified E. coli expression vector pET11d (gift from Dr. Biragyn, National Institute on Aging) in frame with myc/6xHis-Tag at the C-terminus. DNA sequencing was performed to confirm that the generated plasmids contained the correct sequences.

Fig. 1.

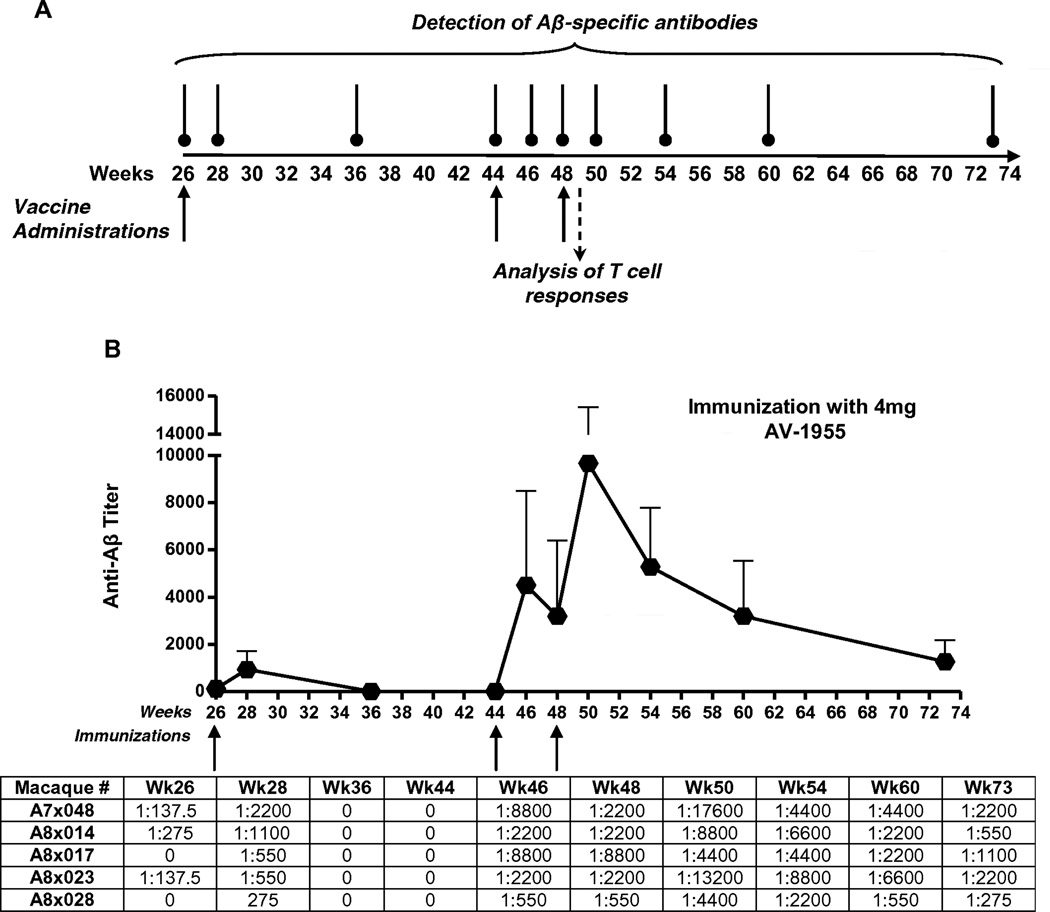

AV-1955 DNA epitope vaccine and experimental overview. (A) Schematic representation of AV-1955 coding a protein consisting of three copies of the first 11 amino acids of human Aβ fused to nine foreign promiscuous T helper (Th) epitopes: synthetic PADRE, five epitopes from tetanus toxin (P23, P32, P21, P30, P2), two epitopes from hepatitis B virus [nuclear capsid protein (HBVnc) and surface antigen (HBsAg)], and one epitope from influenza matrix protein (MT). A signal sequence from the mouse Ig κ-chain is located adjacent to the N-terminus of the first Aβ epitope. (B) The schematic representation of the experimental protocol shows the weeks at which AV-1955 was administered (solid arrows) and the weeks at which blood was drawn for detection of Aβ-specific antibodies (vertical lines above the timeline) or analysis of T cell responses (dashed arrow). N=number of macaques per group.

2.3. Vaccine Administration Procedure

Two groups of five animals each received bilateral administrations of either 0.2 mg (Group 1) or 2 mg (Group 2) of AV-1955 (0.4 or 4 mg total DNA dose per animal, respectively). One group of three animals (Group 3) served as a negative control and received bilateral administrations of 2 mg of a noncoding control vector, pVAX1. All experimental groups received intramuscular injection of plasmid in the quadriceps by EP at weeks 0, 2, 6, and 26, and Groups 2 and 3 received additional administrations at weeks 44 and 48. EP was applied by the TDS-IM (Ichor Medical Systems, San Diego, CA). The electrical pulsing consisted of electrical stimulation at an amplitude of 250 V/cm; the total duration was 40 ms over a 400 ms interval. Blood was collected and serum isolated for analysis of Aβ-specific antibody responses for all three groups at study weeks 0, 2, 4, 8, 17, and 26, and for Groups 2 and 3 at weeks 36, 44, 46, 48, 50, 54, 60, and 73. Blood for analysis of cellular immune responses was collected at weeks 7 and 49 and PBMC were isolated by Ficoll density gradient and stored at −70°C.

2.4. Detection of Aβ-specific antibodies and isotyping

The concentrations of anti-Aβ antibodies were determined by ELISA as described previously [23] with minor modifications. Briefly, 96-well plates (Immunol 2HB; Fisher Scientific, Chino, CA) were coated with 50 µl of 100 µg/ml soluble Aβ42 (pH 9.7, overnight at 4°C). Wells were washed and blocked with 3% BSA in 1x Tris-Tween Buffered Saline (TTBS) overnight, and then 50 µl of sera from experimental and control non-human primates (NHP) were added to the wells at different dilutions. After incubation and washing, HRP-conjugated anti-monkey IgG (1:5000; Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used as a secondary antibody. Plates were incubated and washed, and the reaction was developed by adding 3,3′,5,5′tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Pierce, Rockford, IL) substrate solution and stopped with 2 M H2SO4. The optical density (OD) was read at 450 nm (Biotek, Synergy HT, Winooski, VT). Endpoint titers of antibodies were calculated as the reciprocal of the highest sera dilution that gave a reading twice above the cutoff. The cutoff was determined as the titer of pre-immune sera at the same dilution. For determination of endpoint titers, sera were serially diluted up to 1:19,600 from an initial dilution of 1:137.5. The isotypes of anti-Aβ antibodies were evaluated in week 0 and week 8 serum samples diluted 1:200, using HRP-conjugated anti-monkey IgG (Fitzgerald Industries Intl. Inc., Acton, MA) and IgM (Alpha Diagnostic Intel, Inc., San Antonio, TX) as secondary antibodies at dilutions of 1:50,000 and 1:2,000, respectively. The OD450 values for pre-bleed (week 0) samples were subtracted from the week 8 samples.

2.5. Purification of recombinant proteins

To express His-tagged proteins, the protease deficient E. coli BL21(DE3) strain transformed with pET11d/3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep or pET11d/PADRE-Thep plasmids was grown in LB with 100 µg/ml ampicillin at 28°C to an A600 of 0.8 as described[23]. Gene expression from T7 RNA polymerase in this strain was induced by adding isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 1 mM. Cells were harvested 4h later by centrifugation and used for protein purification. His-tagged proteins were purified as described[23]. Briefly, bacterial cells were suspended in a buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4 [pH 8.0], 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) and the integrity of cells was disrupted by sonication. Over-expressed proteins were accumulated as inclusion bodies and were separated from cell debris using the BugBuster protein extraction reagent as recommended by the manufacturer (Novagen, New Canaan, CT). The final protein pellets were dissolved in 8 M of urea buffer and purified using a Ni-agarose column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Positive fractions were combined and the protein was refolded by dilution in refolding solution (0.1 M Tris HCl, pH 8.0/0.5 M L-arginine/4 mM oxidized glutathione/2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) followed by dialysis against PBS, pH 7.4. Proteins were concentrated using centricon filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The final concentrates of recombinant proteins were analyzed in 10% Bis-Tris gel electrophoresis (NuPAGE Novex Gel, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The level of endotoxin was measured using E-TOXATE kits as recommended by the manufacturer (Sigma, St Louis, MO). An irrelevant protein, BORIS, was purified using the same procedure.

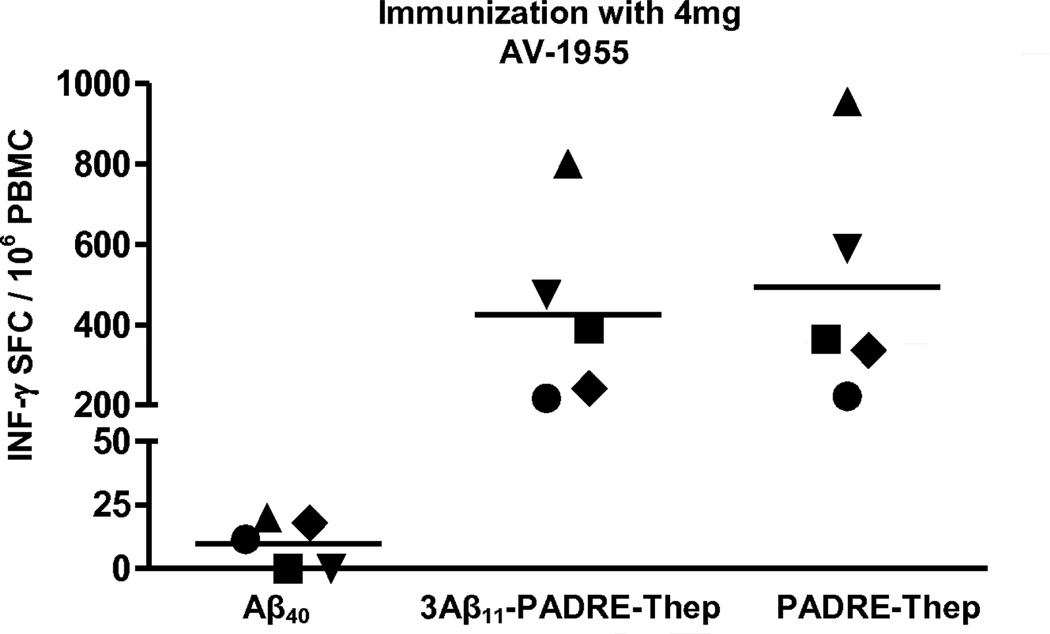

2.6. IFN-γELISPOT assay

Detection of IFN-γ cytokine production in PBMC of rhesus macaques was measured by ELISPOT assay (Mabtech Inc, Cincinnati, OH). PBMCs were collected seven days after the third and sixth immunizations (at week 7 and week 49, respectively). The plates pre-coated with anti-rhesus IFN-γ antibody were washed four times with sterile PBS and blocked with RPMI-10% FBS for 30 minutes at room temperature. Media was removed and PBMC from individual subjects were seeded in triplicate (2×105 cells/well in 100 µl RPMI medium, 10% FBS). Cell cultures were re-stimulated with recombinant proteins (3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep, PADRE-Thep or an irrelevant protein, BORIS) or soluble Aβ40 and irrelevant (Tau2–18) peptides for 20 hours. Of note, we used Aβ40 rather than Aβ42 as the latter is more prone to aggregation so that the range of concentration for the linear dose-dependent response is very narrow. The wells were then decanted and the plates were washed 5 times with PBST. The ELISPOT plates were further incubated with biotinylated detector antibody (2 hours) and HRP-conjugated streptavidin (1 hour) at room temperature. The plates were developed with ready-to-use substrate solution at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by rinsing the wells with water. Spots were counted using a CTL-ImmunoSpot S5 Macro Analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd., Shaker Heights, OH). The difference in the number of SFC (spot forming colonies) per 106 PBMC re-stimulated with vaccine-related proteins and the SFC with 106 PBMC re-stimulated with irrelevant protein was calculated. All peptides and proteins were used at 20µg/ml.

2.7. Purification of anti-Aβ11 antibodies

Anti-Aβ11 antibodies were purified from pooled sera of NHP immunized with the AV-1955 epitope vaccine by an affinity column (SulfoLink, Pierce, Rockford, IL) using an immobilized Aβ28-Cys peptide (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) as described previously[14]. Purified antibodies were analyzed via 10% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

2.8. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis

SPR binding studies were performed on the BIAcore 3000 SPR platform (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) as described previously[14]. Monomeric, oligomeric and fibrillar forms of Aβ42 peptide were prepared as described previously [14] and conformation was confirmed by binding of these peptides by 6E10, A11, and OC antibodies[14, 24]. Peptides were immobilized to the surface of biosensor chip CM5 (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) using 10 mM Na Acetate, pH 5.0. Serial dilutions of affinity purified NHP anti-Aβ11 antibody and NHP irrelevant IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) in the running buffer containing 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.005% surfactant P20, pH 7.4, were injected at 5 µl/min over each immobilized form of peptide, and the kinetics of binding/dissociation were measured as change of the SPR signal (in resonance units). Each injection was followed by a regeneration step consisting of a 12-s pulse of 50 mM NaOH. Fitting of experimental data was done with BIA evaluation 4.1.1 software using a 1:1 interaction model to determine apparent binding constants.

2.9. Detection of Aβ plaques in human brain tissues

Purified anti-Aβ antibodies were screened for the ability to bind to human Aβ plaques using 50 µm brain sections of formalin-fixed cortical tissue from an AD case (received from the Brain Bank and Tissue Repository, MIND, UC Irvine) using immunohistochemistry as previously described[13, 19]. As a secondary antibody, anti-monkey IgG was used (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). A digital camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA) was utilized to capture images of the plaques at a 10x magnification.

2.10. Neurotoxicity assay

A cell culture MTT assay was performed as described previously[25], except that purified monkey anti-Aβ11 antibodies were used, incubation time of cells with peptide and peptide/antibodies was 48 h, and the final concentrations of peptide and antibodies were 2.5 µM and 1.25 µM, respectively.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Statistical parameters (mean, standard deviation (SD), significant difference, etc.) were calculated using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistically significant differences were examined using a two-tailed t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple comparisons post-test (a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant).

3. Results

3.1. Immunogenicity and dose responses to AV-1955 by rhesus macaques

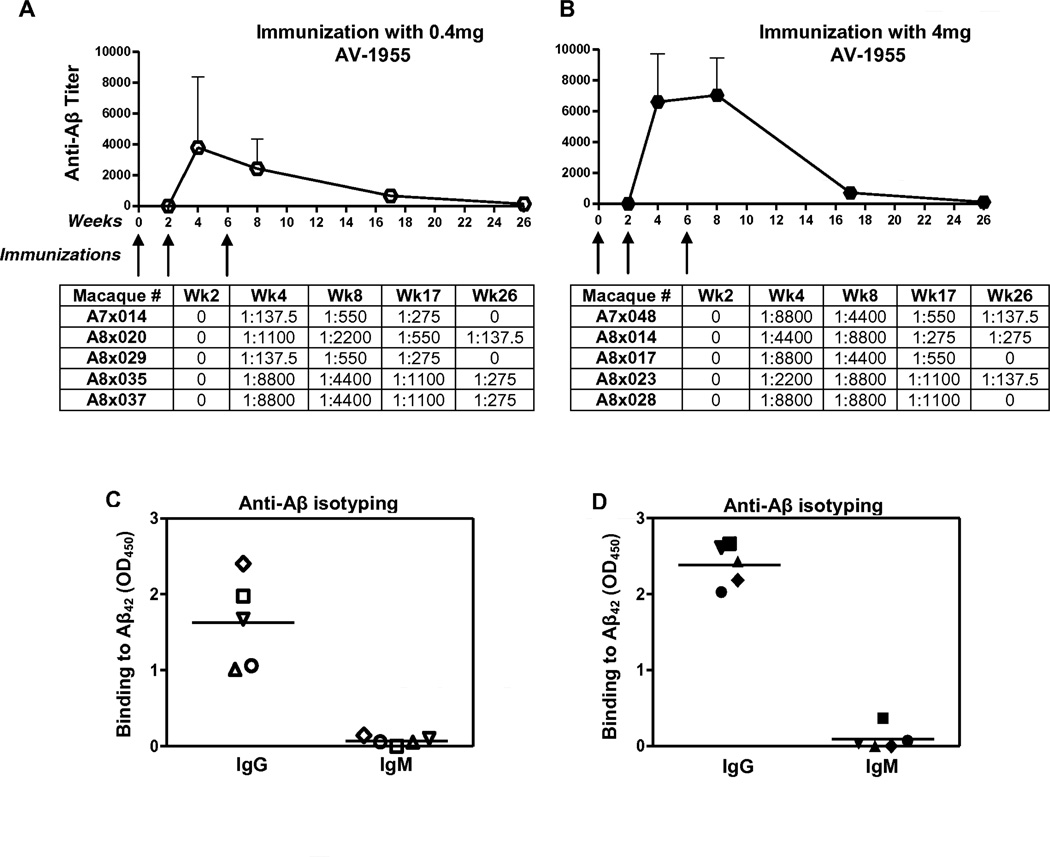

Since immune responses to conventionally-delivered DNA vaccines have been generally weak[26], EP-mediated delivery with TDS-IM, which has been shown to be effective in humans[27], was selected as a means of enhancing the potency of the AV-1955 in rhesus macaques. For the initial evaluation of immunogenicity, the vaccine was administered at weeks 0, 2, and 6 to groups of five NHP using a dose of 0.4 mg (group #1) or 4 mg (group #2), while a control group of three NHP was injected with 4 mg of the empty vector (Fig. 1B). In the first phase of the study, serum was collected and anti-Aβ antibodies were detected at weeks 0, 2, 4, 8, 17 and 26 (Fig. 1B). Robust humoral immune responses were induced by two weeks after the second immunization in both dose groups with significantly higher antibody titers (p<0.05) generated in the 4 mg dose group compared to the 0.4 mg group after the third immunization. Aβ-specific antibodies were still detected in all animals at week 17, i.e., 11 weeks after the third immunization (Fig. 2A,B). At week 26, low titers of antibodies were present in three animals from both the low and high dose groups (Fig. 2A, B). As expected, Aβ-specific antibodies were not detected in the negative control group (data not shown). Isotyping of the antibodies in serum at study week 8 showed that the vast majority of the Aβ-specific antibodies were IgG in both dose groups (Fig. 2C, D), suggesting the presence of vaccine-specific Th cells.

Fig. 2.

AV-1955 induces high titers of anti-Aβ antibodies of IgG isotype in rhesus macaques. (A, B) Mean Aβ-specific endpoint antibody titers were evaluated in sera of macaques. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Animals received either 0.4 mg (A, C) or 4 mg (B, D) of DNA vaccine delivered by EP. The titers for individual animals are listed below the graphs. (C, D) IgG and IgM isotypes of antibodies were analyzed in sera of individual animals after the third immunization. Horizontal lines indicate mean OD450.

Next we measured cellular immune responses in PBMC isolated from all experimental and control macaques using an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. As shown in Fig. 3 A and B, IFN-γ producing cells were detected in PBMC from the groups receiving the AV-1955 after re-stimulation with the recombinant protein, 3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep. Responses were significantly higher (p<0.05) in the group receiving 4 mg of vaccine compared to the lower dose group. Importantly, the numbers of IFN-γ producing cells after Aβ40 re-stimulation of PBMC from macaques immunized with 0.4 mg or 4 mg doses of AV-1955 remained at background levels. As anticipated, re-stimulation of PBMC isolated from three animals receiving the control vector with either 3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep or Aβ40 did not activate cellular immune responses (Fig.3C). These data demonstrate that AV-1955 delivered with EP induced significant cellular immune responses to the portion of the vaccine containing the foreign Th cell epitopes, and these responses correlate with the robust humoral immune responses specific to Aβ42 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

AV-1955 induces strong cellular immune responses specific to foreign Th epitopes, but not to Aβ40. (A, B, C) Cellular immune responses were evaluated by ELISPOT assay in PBMC isolated from blood obtained at week 7, one week after the third AV-1955 administration or injection of vector. PBMC were re-stimulated with Aβ40 peptide or with the recombinant protein (3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep) encoded by the AV-1955 plasmid. The number of IFN-γ secreting cells is depicted as SFC (spot-forming colonies) for individual macaques that received 0.4 mg (A) or 4 mg (B) of AV-1955, or 4 mg of pVAX1 (C). Horizontal lines depict the mean responses. (D) Comparison of humoral and cellular immune responses in macaques immunized three times with different doses of AV-1955.

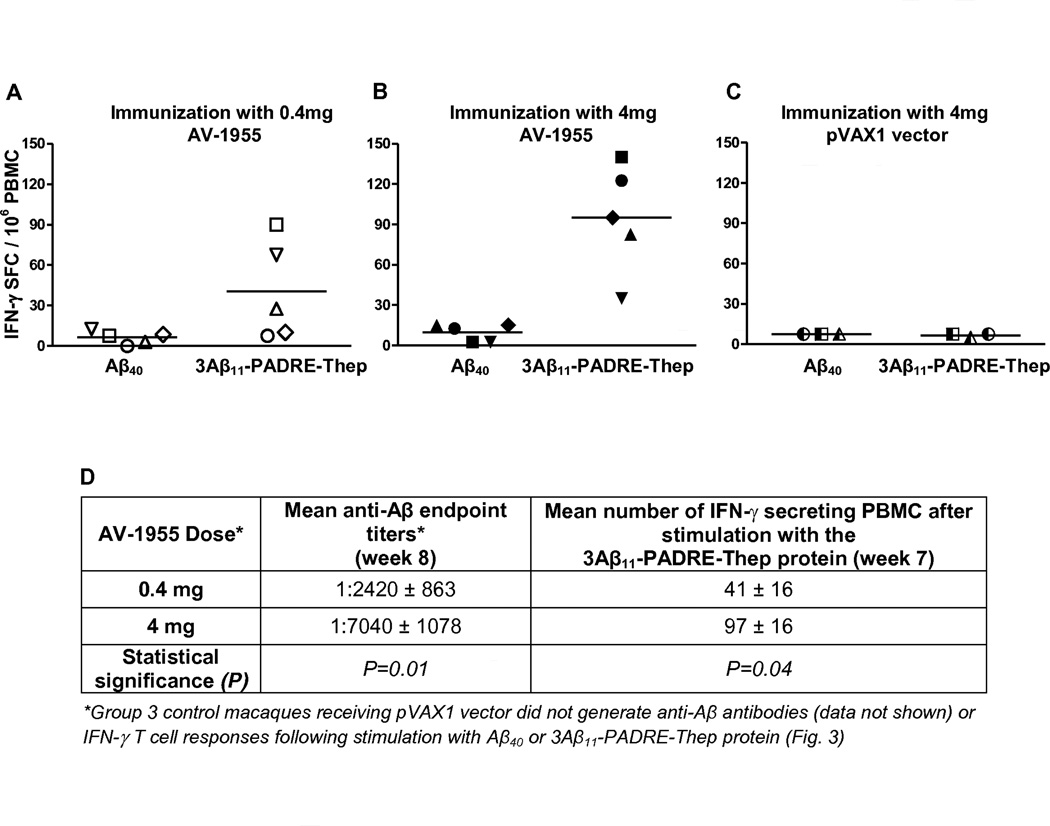

3.2. Functional characteristics of the rhesus Aβ-specific antibodies

The functionality of the antibodies generated in response to vaccination with AV-1955 was investigated using three different approaches. First, we tested whether the purified macaque antibodies bind to amyloid plaques in the brain sections from cases with AD. As seen in Fig. 4A, anti-Aβ antibodies generated by immunization with the AV-1955 bound to Aβ deposits in the frontal cortex of an AD subject similarly to 6E10, a monoclonal antibody specific for human Aβ (positive control). As expected, irrelevant control IgG did not bind to the brain sections (Fig. 4A). Of note, anti-Aβ antibodies purified from immune macaques did not bind to brain sections from a non-AD subject (data not shown). Thus, the DNA epitope vaccine induced antibodies capable of binding to amyloid plaques in brain sections from an AD patient.

Fig. 4.

Anti-Aβ11 antibodies induced by AV-1955 exhibit functional activities. (A) NHP anti-Aβ, but not irrelevant NHP IgG, bound to amyloid β deposits in brain sections from an the AD case. The mouse monoclonal antibody, 6E10, which is specific for human Aβ, was used as a positive control for amyloid β deposits in the AD subject. The original magnification was 10x and the scale bar is 100 µm. (B) Surface plasmon resonance assay was used to generate sensorgram overlays that depict the binding of different concentrations of purified NHP anti-Aβ11 antibodies to immobilized Aβ monomers, oligomers (Oligo), and fibrils. (C) Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were incubated with Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils, in the presence or absence of anti-Aβ11 antibody or irrelevant rabbit IgG. Control cells were treated with vehicle, and cell viability was assayed in all cultures using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Data were collected (four replicates) and expressed as percentages of control ± SD.

Second, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay was used to evaluate the binding affinity of purified Aβ-specific macaque antibodies to different forms of Aβ42. As shown in Fig. 4B, anti-Aβ antibodies bound to immobilized Aβ monomers, oligomers, and fibrils with high affinity (KD =19.2±0.4×10−8 M,2.52±0.06×10−8M and 9.96±0.04×10−8M,respectively),while binding of irrelevant monkey IgG to these peptides was not detected (data not shown). The binding affinity of antibodies to oligomers,the most toxic forms of Aβ42[28], was significantly higher than to fibrils and monomers (P<0.0001). In addition, the binding affinity of the antibodies to fibrils was significantly higher than to monomeric peptide (P<0.0001). Thus, immunization of NHP with the AV-1955 resulted in the production of antibodies capable of binding to multiple forms of the Aβ42 peptide with the highest affinity to oligomeric forms.

Finally, cytotoxicity assays were performed to determine whether the Aβ-specific antibodies could protect SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells from Aβ42 oligomer- and fibril-mediated neurotoxicity. As seen in Fig. 4C, oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ42 were cytotoxic, reducing neuroblastoma cell viability by 44% and 63% compared to untreated cells, respectively. Preincubation of Aβ42 oligomers and fibrils with anti-Aβ antibodies protected the cells from the cytotoxic effects of these Aβ42 forms, with cell viability increased to 82% and 94%, respectively. In contrast, preincubation of oligomers or fibrils with a control irrelevant monkey IgG did not protect the neuroblastoma cells from cytotoxicity of these peptides. These data demonstrated that the NHP anti-Aβ antibodies were able to inhibit Aβ42 fibril- and oligomer-mediated neurotoxicity (Fig. 4C).

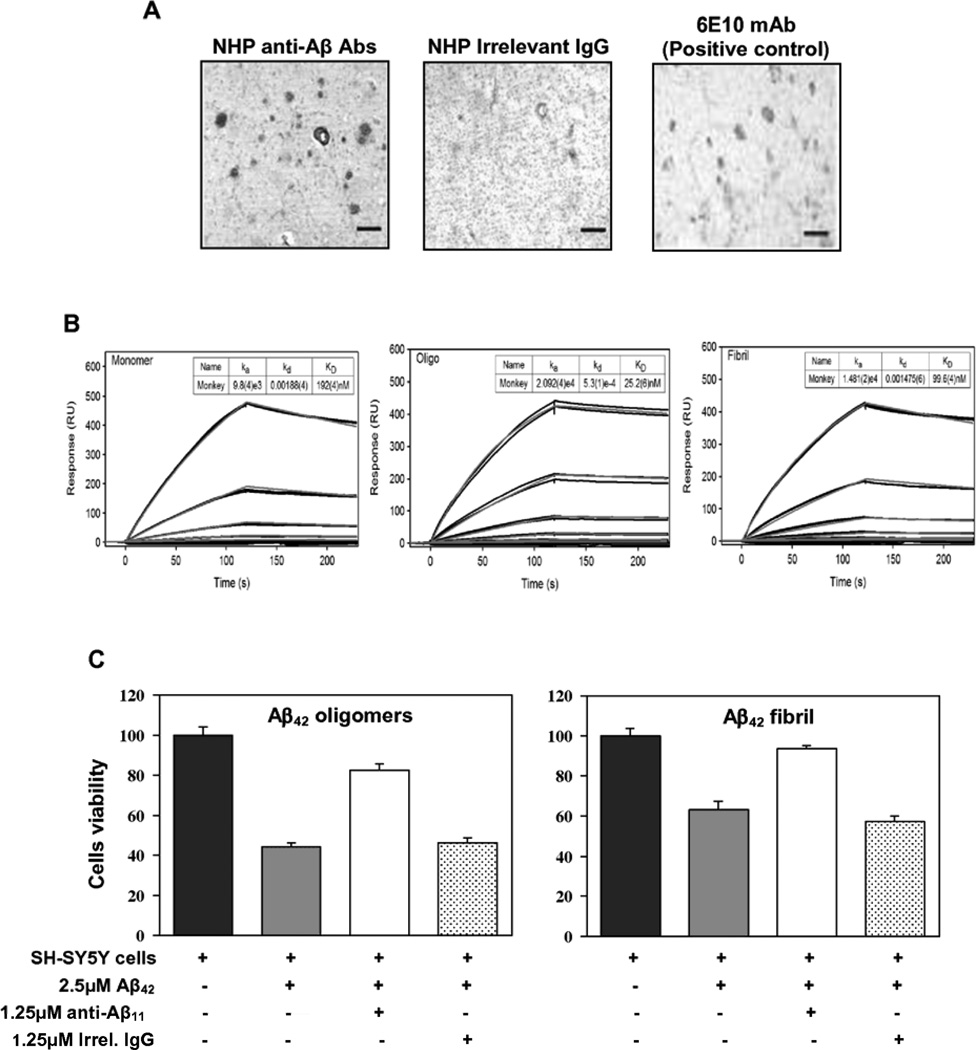

3.3. Longitudinal dynamics of immune responses in response to AV-1955

Since the high dose (4 mg) AV-1955 group showed significantly higher antibody and T cell responses after three immunizations, the immunogenicity study was extended in this and control vector groups for an additional 11 months in order to gain more insight into the kinetics and magnitude of immune responses (Fig. 5A). Thus, in the second phase of this study, experimental macaques were boosted with AV-1955 delivered with EP at weeks 26, 44, and 48, while control animals were administered 4 mg of the vector backbone with EP on the same days. Anti-Aβ antibodies were measured in the sera collected from all control and immunized macaques at weeks 28, 36, 44, 46, 48, 50, 54, 60, and 73.

Fig. 5.

Longitudinal dynamic of humoral immune responses to AV-1955 in macaques. Mean Aβ-specific endpoint antibody titers were evaluated in sera of macaques receiving additional immunizations with 4 mg of the AV-1955 vaccine at weeks 26, 44 and 48. Error bars indicate standard deviation. The titers for individual animals are listed below the graph.

Immunization of macaques after 20 weeks resting period (at week 26) increased anti-Aβ antibody concentrations somewhat by week 28 but at week 36, titers had declined to undetectable levels (Fig. 5B). However, after another 18 week resting period, administration of AV-1955 (at week 44) induced significantly higher level of humoral immune responses: the antibody titers two weeks after this fifth immunization increased to the levels detected after the second and third administrations. An additional immunization at week 48 boosted the levels of antibodies even higher (Fig. 5B). Importantly, analyses of anti-Aβ antibody levels at different time points after the last immunization with AV-1955 showed that it declines very slowly, indicating the longevity of humoral immune responses. In fact, 25 weeks after the last immunization, titers of antibodies remained relatively high through the most recent time point tested, week 73 (Fig. 5B).

Next, cellular immune responses were evaluated at week 49, one week after the sixth immunization, in PBMC collected from immune and control macaques. As shown in Fig. 6, immunization of NHP with AV-1955 at week 48 boosted cellular immune responses: high numbers of PBMC re-stimulated with 3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep protein produced IFN-γ. These cellular immune responses were approximately 4–5 times higher than that detected in the same macaques after 3 immunizations with AV-1955 (Fig 3B,D versus Fig 6). Of note, immune PBMC were also re-stimulated with recombinant protein lacking Aβ sequences (PADRE-Thep). The data demonstrated that both proteins activated similar numbers of cells producing IFN-γ, suggesting that AV-1955 activated cells specific to the portion of the vaccine encoding the Th epitopes but not to the Aβ11 epitope. Importantly, Aβ40 re-stimulation of PBMC from macaques administrated AV-1955 six times resulted in background levels of IFN-γ producing cells (Fig. 6). Collectively, these data clearly demonstrate that even after six immunizations with AV-1955, no autoreactive Aβ-specific cellular immune responses were elicited, while desirable cellular immune responses specific to foreign Th epitopes were maintained. In keeping with these results, a key finding in this study is that no vaccine-related adverse events were observed in the study animals after 18 months and six vaccine administrations.

Fig. 6.

Strong cellular immune responses specific to the protein containing the foreign Th epitopes, but not to the Aβ40 peptide were detected after six immunizations with AV-1955. T cell responses were evaluated by ELISPOT assay in PBMC isolated from blood obtained at week 49, one week after the sixth vaccine administration (4 mg dose group). PBMC were re-stimulated with Aβ40 peptide, with the recombinant protein (3Aβ11-PADRE-Thep) encoded by the AV-1955 plasmid, or with a recombinant protein (PADRE-Thep) containing only the nine T helper epitopes. The number of IFN-γ secreting cells is depicted as SFC for individual macaques. Horizontal lines depict the mean response.

4. Discussion

Since the failure of the AN-1792 clinical trial and the identification of serious safety issues therein, many other trials have been initiated evaluating passive administration of Aβ-specific antibodies or active vaccination with newly generated AD epitope vaccines. Recently announced results of Phase III clinical trials that evaluated passive transfer of two monoclonal antibodies (bapineuzumab and solanezumab) in patients with mild to moderate AD indicated that the cognitive and functional primary endpoints were not met[29–32]. However, some reduction of the amyloid burden and a significant decrease of CSF p-tau were detected in ApoE ε4 non-carrier patients receiving 1 mg/kg of bapineuzumab. In addition, administrations of 0.5 mg/kg of bapineuzumab significantly reduced the amyloid burden and CSF p-tau in ApoE ε4 carriers in Pfizer/Janssen Alzheimer’s Immunotherapy Program studies[31, 32]. Although Phase III trials of solanezumab also did not reach their primary endpoints in two separate studies conducted by Eli Lilly, analysis of pooled data from both studies showed a statistically significant slowing of cognitive decline in vaccinated patients with mild, but not moderate AD[29]. Thus, data from these passive vaccination trials suggest that immunotherapy should be initiated at the earliest stages of AD or even in asymptomatic individuals at risk of developing AD to minimize synaptic and neuronal loss. However, since passive transfer of Aβ-specific antibody is impractical for long-term preventative or for early therapeutic application in AD due to the high cost and logistical issues intrinsic to repeated intravenous administration of humanized monoclonal antibodies, active immunization approaches offer the potential for sustainable clinical and commercial advantages.

Collectively, results of the AN-1792 and passive administrations trials with anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies have provided important information relevant to the development of a safe and effective immunotherapy for AD. First, active immunotherapy should induce the target anti-Aβ responses without activation of autoreactive T cells. Second, active immunotherapy should be initiated before toxic forms of the Aβ peptide accumulate in the brain. Accordingly, several epitope-based vaccines have been developed and are being tested in preclinical studies [9, 13, 15, 16, 33–37] and some of these vaccines (CAD106, ACC-001, V950, UB311, AFFITOPE AD01–03) are being evaluated clinically[8, 38–41]. In most of the epitope vaccines, the N-terminus of Aβ is used as the B cell epitope, although the AFFITOPE vaccines are composed of peptide mimotopes of the N-terminus[41]. Currently, the only results published from active vaccination clinical trials are for the original AN-1792 trials, the AFFITOPE vaccines AD01 and AD02 [42] , and the CAD106 vaccine[38]. Although immunogenicity data generated with the AFFITOPE AD01 and AD02 vaccines have not been published, the vaccines were shown to be safe and well tolerated in initial clinical trials [42] . CAD106 is composed of Aβ1–6 B cell epitope coupled to the coat protein of bacteriophage Qβ on the surface of virus-like particles. Recently published results from a Phase I trial of CAD106 in subjects with mild-to-moderate AD indicated that the vaccine demonstrated safety and tolerability. Antibody responses directed to Aβ were detected in 62% of low dose and 82% of high dose subjects; however, quantification of the antibody titers was done relative to serum from rhesus macaques immunized with CAD106, making it difficult to interpret the actual magnitude of the responses[38].

To date, only a few papers have been published on the immunogenicity of AD vaccines in NHP. Full length Aβ42 immunogens, either in fibrillar form [43, 44] or encoded by a DNA vaccine [45, 46] have been evaluated, while three other papers describe AD epitope vaccines[36, 37, 47]. CAD106 immunization of rhesus macaques promoted the generation of Aβ-specific antibodies, and although the titers were not reported, the antibodies were shown to have some functional properties suggestive of potential therapeutic activity[37]. Therapeutically potent anti-Aβ antibodies were reported in macaques immunized with UBITh, a vaccine composed of two peptides consisting of Aβ1–14 fused with a Th epitope modified either from measles virus F protein or hepatitis B surface antigen, and formulated with CpG oligonucleotides plus aluminum mineral salt adjuvants[36]. High titers of anti-Aβ antibodies were detected in sera of four baboons; however, the levels of humoral immune responses in cynomolgus macaques were not reported.

In studies described in this paper, we are reporting for the first time on the immunogenicity of a DNA-based epitope vaccine, AV-1955, in rhesus macaques. Administration of AV-1955 with EP induced strong anti-Aβ42 IgG antibody responses in all animals from both low and high dose groups (Fig. 2). The antibody responses were long lasting and were detected in all animals 11 weeks after the third immunization and even after 20 weeks, three animals in each group had detectable anti-Aβ antibodies (Fig 2). For an unknown reason, boosting of humoral immune responses in macaques from the high dose group immunized for the 4th time with AV-1955 after 20 weeks of resting period (at week 26) was relatively weak. However, additional vaccinations at weeks 44 and 48 boosted the antibody response quite well (Fig. 5) and titers of antibodies were maintained through week 73 (Fig 5B). As observed in this study, in humans an initial series of priming immunizations followed by a rest period before further administrations may be effective in generating long-term production of Aβ-specific antibodies. Further studies of the AV-1955 vaccine in NHP will aid in understanding the kinetics of Aβ-specific antibody responses in primates, which can be applied to initial trials of the vaccine in humans. Importantly, AV-1955 induced anti-Aβ42 specific IgG antibodies that have functional characteristics suggesting they may have therapeutic potential since they (i) bound to amyloid plaques on brain sections from an AD case but not to control brain sections; (ii) bound to multiple forms of the Aβ42 peptide with high affinity; and (iii) inhibited Aβ42 fibril- and oligomer-mediated neurotoxicity (Fig. 4). After six immunizations, the vaccine was well tolerated with no adverse events occurring that were attributable to the administration of the vaccine or the resultant generation of high titers of anti-Aβ42 antibodies.

In addition to Aβ specific antibody responses, we reported on the induction of antigen-specific cellular immune responses by AV-1955. Importantly, these responses were detected only to the portion of the vaccine containing foreign Th epitopes, and not to Aβ (Fig. 3, 6). This is a key observation since robust antibody responses require strong antigen-specific Th cell responses, and the results demonstrate that the strategy of incorporating multiple foreign Th epitopes into the vaccine design successfully elicited strong anti-Aβ antibody responses (Fig.2, 5 ). Even after six administrations of the AV-1955 vaccine, cellular immune responses specific for the Aβ self peptide were not detected, further supporting the safety of our epitope-based vaccine design (Fig. 6).

The data presented above indicate that the AV-1955 DNA epitope vaccine induces strong humoral and cellular immune responses in macaques when delivered by EP. Since the DNA vaccine must be in the cell nucleus for antigen expression to occur, a significant factor contributing to these results is high efficiency of intracellular DNA uptake associated with EP-mediated DNA delivery[48]. Importantly, the DNA vaccine strategy allowed us to incorporate a promiscuous synthetic Th cell epitope (PADRE) as well as eight promiscuous Th cell epitopes from antigens that most people have encountered either through vaccination or natural infection so that pre-existing memory Th cell responses to these epitopes may be present in adults. Due to the limited availability of aged, naïve macaques, macaques utilized in this study were relatively young (~ 3 years at study initiation). Thus, additional non-clinical and/or clinical studies will be necessary to address the possibility of vaccine hyporesponsiveness by aged immune systems in elderly subjects. However, it should be noted that this possibility was the basis for incorporating foreign promiscuous Th cell epitopes from circulating and vaccine-associated human pathogens in the AV-1955 vaccine design were included in the AV-1955 vaccine design. Memory Th cells specific for these Th epitopes present in elderly humans would be expected to be activated upon immunization with the AV-1955, resulting in rapid and robust anti-Aβ responses. This strategy may be particularly important because of the potential to help overcome impaired responses of the elderly to vaccines. In fact, we recently directly demonstrated the feasibility of this strategy in mice; a single immunization with an AD epitope vaccine strongly activated pre-existing memory CD4+ T cells specific to the Th epitopes of this recombinant protein vaccine and rapidly led to the robust production of antibodies specific to small N-terminal Aβ epitope of the same vaccine[49].

It has become quite clear in recent years that one of the key issues for successful immunotherapy of AD is that there must be a means of providing the therapy early in the disease course so that formation of toxic forms of Aβ42 and plaque formation can be inhibited well before extensive neuropathology occurs. Early identification of at-risk individuals or individuals with mild cognitive impairment is likely essential for successful disease prevention/intervention. Current approaches to identify at-risk and early stage subjects are aimed primarily at identification of disease-predictive or disease-associated biomarkers. These include detection of changes in blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) components, for example, reduced levels of Aβ42 and increased levels of p-tau in CSF, and imaging approaches such as using the amyloid-imaging positron emission tomography (PET) tracer, Pittsburgh Compound-B (PIB)[50]. The ability to initiate Aβ-directed immunotherapy in at-risk individuals or those with very early stage cognitive impairment will depend largely on the safety of the immunotherapy. AV-1955 has thus far safely elicited high titer Aβ-specific antibodies with functional characteristics suggesting they may have therapeutic potential. There were no observed differences in general health status between experimental and control groups during immunization or follow up. The presence of cellular immune responses specific for the foreign Th cell epitopes incorporated into the vaccine combined with the absence of detectable cellular anti-Aβ responses provide support for the design of the AV-1955 vaccine candidate. Importantly, the anti-Aβ responses were induced without adverse effects in rhesus macaques for almost 18 months. These data indicate that continued development of AV-1955 with the objective of initiating human clinical testing is warranted.

Research in Context.

Systematic review

Immunotherapy is a promising treatment to prevent, slow down or stop the development and progression of AD. It is believed that it will be the most effective in improvement of cognitive and/or functional performance in patients if administered early in the course of the disease. Active immunization is a more desirable approach for prevention of AD and offering the potential for sustainable clinical and commercial advantages.

Interpretation

DNA-based epitope vaccine AV-1955 composed of a short Aβ B cell epitope, conjugated to the string of foreign Th cell epitopes is a prospective candidate for prevention of AD. Delivered by EP system it generated strong cellular immune responses to foreign epitopes, eliminated activation of autoreactive T cells, induced strong and therapeutically potent anti-Aβ antibodies, diminished variability of immune responses due to MHC Class II diversity in macaques.

Future directions

By completion of preclinical safety/toxicity studies human clinical testing of AV-1955 vaccine will be initiated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jason Goetzmann at the New Iberia Research Center for his assistance in overseeing the macaque study. We are grateful to Barry Ellefsen and Lacey Tichenor from Ichor Medical Systems for their invaluable help coordinating this study. We acknowledge the expert assistance Shari Piaskowski from Watkins Lab, UW AIDS Vaccine lab (Madison, WA), during the optimization of the monkey ELISPOT assay. In addition, we thank Dr. David Mitzka at Biosensor Tools, Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT) for performing the SPR experiments. This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U44NS065518; “A Therapeutic DNA Epitope Vaccine for Alzheimer's Disease”). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders And Stroke or the National Institutes of Health. H.D. was supported by NIA T32 training grant (AG000096). AD case tissues were provided by UCI ADRC (Grant P50-AG16573).

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s diseas

- Aβ

amyloid β

- Th epitope

T helper epitope

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- Tg

transgenic

- PADRE

Pan DR Epitope

- GG

gene gun

- EP

electroporation

- TDS-IM

TriGrid Delivery System, intramuscular

- TT

Tetanus Toxin

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface Antigen

- HBVnc

Hepatitis B nuclear capsid protein

- MT

Influenza Matrix protein

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- PBMC

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell

- NHP

Non-Human Primate

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM

Immunoglobulin M

- IFN-γ

Interferon, Gamma

- SPR

Surface Plasmon Resonance

- SD

Standard Deviation

- PET

Positron Emission Tomography

- PIB

Pittsburgh Compound-B

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement: C.F. Evans and D. Hannaman are full-time employees of Ichor Medical Systems.

References

- 1.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–185. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cerpa W, Dinamarca MC, Inestrosa NC. Structure-function implications in Alzheimer's disease: effect of Abeta oligomers at central synapses. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2008 Jun;5(3):233–243. doi: 10.2174/156720508784533321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanzi RE. The genetics of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(10) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, et al. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-beta protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005 Jan;8(1):79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Feb;8(2):101–112. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse [see comments] Nature. 1999;400(6740):173–177. doi: 10.1038/22124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan D. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease. J Intern Med. 2011 Jan;269(1):54–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02315.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobello K, Ryan JM, Liu E, Rippon G, Black R. Targeting Beta amyloid: a clinical review of immunotherapeutic approaches in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:628070. doi: 10.1155/2012/628070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghochikyan A. Rationale for peptide and DNA based epitope vaccines for Alzheimer's disease immunotherapy. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009 Apr;8(2):128–143. doi: 10.2174/187152709787847298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spires-Jones TL, Mielke ML, Rozkalne A, Meyer-Luehmann M, de Calignon A, Bacskai BJ, et al. Passive immunotherapy rapidly increases structural plasticity in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009 Feb;33(2):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):916–919. doi: 10.1038/78682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kotilinek LA, Bacskai B, Westerman M, Kawarabayashi T, Younkin L, Hyman BT, et al. Reversible memory loss in a mouse transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2002 Aug 1;22(15):6331–6335. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06331.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agadjanyan MG, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Vasilevko V, Movsesyan N, Mkrtichyan M, et al. Prototype Alzheimer's disease vaccine using the immunodominant B cell epitope from beta-amyloid and promiscuous T cell epitope pan HLA DR-binding peptide. J Immunol. 2005 Feb 1;174(3):1580–1586. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mamikonyan G, Necula M, Mkrtichyan M, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Movsesyan N, et al. Anti-Abeta 1–11 antibody binds to different beta-amyloid species, inhibits fibril formation, and disaggregates preformed fibrils, but not the most toxic oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2007 Jun 1;282:22376–22386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700088200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrushina I, Ghochikyan A, Mktrichyan M, Mamikonyan G, Movsesyan N, Davtyan H, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Peptide Epitope Vaccine Reduces Insoluble But Not Soluble/Oligomeric A{beta} Species in Amyloid Precursor Protein Transgenic Mice. J Neurosci. 2007 Nov 14;27(46):12721–12731. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3201-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Movsesyan N, Ghochikyan A, Mkrtichyan M, Petrushina I, Davtyan H, Olkhanud PB, et al. Reducing AD-like pathology in 3xTg-AD mouse model by DNA epitope vaccine- a novel immunotherapeutic strategy. PLos ONE. 2008;3(5):e21–e4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davtyan H, Ghochikyan A, Movsesyan N, Ellefsen B, Petrushina I, Cribbs DH, et al. Delivery of a DNA Vaccine for Alzheimer's Disease by Electroporation versus Gene Gun Generates Potent and Similar Immune Responses. Neurodegener Dis. 2012 Feb 1;10(1–4):261–264. doi: 10.1159/000333359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Drunen, Littel-van, den Hurk S, Hannaman D. Electroporation for DNA immunization: clinical application. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010 May;9(5):503–517. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Movsesyan N, Mkrtichyan M, Petrushina I, Ross TM, Cribbs DH, Agadjanyan MG, et al. DNA epitope vaccine containing complement component C3d enhances anti-amyloid-beta antibody production and polarizes the immune response towards a Th2 phenotype. J Neuroimmunol. 2008 Dec 15;205(1–2):57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baraldo K, Mori E, Bartoloni A, Petracca R, Giannozzi A, Norelli F, et al. N19 polyepitope as a carrier for enhanced immunogenicity and protective efficacy of meningococcal conjugate vaccines. Infect Immun. 2004 Aug;72(8):4884–4887. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4884-4887.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James EA, Bui J, Berger D, Huston L, Roti M, Kwok WW. Tetramer-guided epitope mapping reveals broad, individualized repertoires of tetanus toxin-specific CD4+ T cells and suggests HLA-based differences in epitope recognition. Int Immunol. 2007 Nov;19(11):1291–1301. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee M, Bard F, Johnson-Wood K, Lee C, Hu K, Griffith SG, et al. Abeta42 immunization in Alzheimer's disease generates Abeta N-terminal antibodies. Ann Neurol. 2005 Sep;58(3):430–435. doi: 10.1002/ana.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davtyan H, Mkrtichyan M, Movsesyan N, Petrushina I, Mamikonyan G, Cribbs DH, et al. DNA prime-protein boost increased the titer, avidity and persistence of anti-Abeta antibodies in wild-type mice. Gene Ther. 2010 Feb;17(2):261–271. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kayed R, Head E, Sarsoza F, Saing T, Cotman CW, Necula M, et al. Fibril specific, conformation dependent antibodies recognize a generic epitope common to amyloid fibrils and fibrillar oligomers that is absent in prefibrillar oligomers. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davtyan H, Ghochikyan A, Cadagan R, Zamarin D, Petrushina I, Movsesyan N, et al. The immunological potency and therapeutic potential of a prototype dual vaccine against influenza and Alzheimer's disease. J Transl Med. 2011 Aug 1;9(1):127. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ulmer JB, Wahren B, Liu MA. DNA vaccines: recent technological and clinical advances. Discov Med. 2006 Jun;6(33):109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasan S, Hurley A, Schlesinger SJ, Hannaman D, Gardiner DF, Dugin DP, et al. In vivo electroporation enhances the immunogenicity of an HIV-1 DNA vaccine candidate in healthy volunteers. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):19252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, et al. Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 May 26;95(11):6448–6453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eli Lilly and Company Announces Top-Line Results on Solanezumab Phase 3 Clinical Trials in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Available at http://newsroom.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=702211.

- 30.Johnson & Johnson Announces Discontinuation Of Phase 3 Development of Bapineuzumab Intravenous (IV) In Mild-To-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. Found at http://www.jnj.com/connect/news/all/johnson-and-johnson-announces-discontinuation-of-phase-3-development-of-bapineuzumab-intravenous-iv-in-mild-to-moderate-alzheimers-disease.

- 31.Sperling R, Salloway S, Raskind MA, Ferris S, Liu E, Yuen E, et al. 16th Congress of the European Federation of Neurological Societies. 2012. A randomized double-blind, placebocontrolled clinical trila of intravenous bapineuzumab in patients with Alzheimer's disease who are apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers. Stokholm Sweden 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salloway S, Sperling R, Honig L, Porsteinsson A, Sabbagh M, Liu E, et al. 16th Congress of the European Federation of Neurological Societies. 2012. A randomized double-blind, placebocontrolled clinical trila of intravenous bapineuzumab in patients with Alzheimer's disease who are apolipoprotein E ε4 non-carriers. Stokholm Sweden 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cribbs DH. Abeta DNA vaccination for Alzheimer's disease: focus on disease prevention. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010 Apr;9(2):207–216. doi: 10.2174/187152710791012080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olkhanud PB, Mughal M, Ayukawa K, Malchinkhuu E, Bodogai M, Feldman N, et al. DNA immunization with HBsAg-based particles expressing a B cell epitope of amyloid beta-peptide attenuates disease progression and prolongs survival in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Vaccine. 2012 Feb 21;30(9):1650–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim HD, Jin JJ, Maxwell JA, Fukuchi K. Enhancing Th2 immune responses against amyloid protein by a DNA prime-adenovirus boost regimen for Alzheimer's disease. Immunol Lett. 2007 Sep 15;112(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CY, Finstad CL, Walfield AM, Sia C, Sokoll KK, Chang TY, et al. Site-specific UBITh amyloid-beta vaccine for immunotherapy of Alzheimer's disease. Vaccine. 2007 Apr 20;25(16):3041–3052. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiessner C, Wiederhold KH, Tissot AC, Frey P, Danner S, Jacobson LH, et al. The second-generation active Abeta immunotherapy CAD106 reduces amyloid accumulation in APP transgenic mice while minimizing potential side effects. J Neurosci. 2011 Jun 22;31(25):9323–9331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0293-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winblad B, Andreasen N, Minthon L, Floesser A, Imbert G, Dumortier T, et al. Safety, tolerability, and antibody response of active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in patients with Alzheimer's disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, first-in-human study. Lancet Neurol. 2012 Jul;11(7):597–604. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabira T. Immunization therapy for Alzheimer disease: a comprehensive review of active immunization strategies. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2010;220(2):95–106. doi: 10.1620/tjem.220.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lemere CA, Masliah E. Can Alzheimer disease be prevented by amyloid-beta immunotherapy? Nat Rev Neurol. 2010 Feb;6(2):108–119. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delrieu J, Ousset PJ, Caillaud C, Vellas B. ‘Clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease':immunotherapy approaches. J Neurochem. 2012 Jan;120(Suppl 1):186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneeberger A, Mandler M, Mattner F, Schmidt W. AFFITOME(R) technology in neurodegenerative diseases: the doubling advantage. Hum Vaccin. 2010 Nov;6(11):948–952. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.11.13217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gandy S, DeMattos RB, Lemere CA, Heppner FL, Leverone J, Aguzzi A, et al. Alzheimer A beta vaccination of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18(1):44–46. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lemere CA, Beierschmitt A, Iglesias M, Spooner ET, Bloom JK, Leverone JF, et al. Alzheimer's disease abeta vaccine reduces central nervous system abeta levels in a non-human primate, the Caribbean vervet. Am J Pathol. 2004 Jul;165(1):283–297. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63296-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qu BX, Xiang Q, Li L, Johnston SA, Hynan LS, Rosenberg RN. Abeta42 gene vaccine prevents Abeta42 deposition in brain of double transgenic mice. J Neurol Sci. 2007 Sep 15;260(1–2):204–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tokita Y, Kaji K, Lu J, Okura Y, Kohyama K, Matsumoto Y. Assessment of non-viral amyloid-beta DNA vaccines on amyloid-beta reduction and safety in rhesus monkeys. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(4):1351–1361. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li S, Wang H, Lin X, Xu J, Xie Y, Yuan Q, et al. Specific humoral immune responses in rhesus monkeys vaccinated with the Alzheimer's disease-associated beta-amyloid 1–15 peptide vaccine. Chinese Medical Journal. 2005;118(i8):660–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sardesai NY, Weiner DB. Electroporation delivery of DNA vaccines: prospects for success. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011 Jun;23(3):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davtyan H, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Davtyan A, Poghosyan A, et al. Immunogenicity, Efficacy, Safety, and Mechanism of Action of Epitope Vaccine (Lu AF20513) for Alzheimer's Disease: Prelude to a Clinical Trial. J Neurosci. 2013 Mar 13;33(11):4923–4934. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4672-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klunk WE. Amyloid imaging as a biomarker for cerebral beta-amyloidosis and risk prediction for Alzheimer dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 Dec 32;1(Suppl):S20–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]