Abstract

This study evaluated the immigrant paradox by ascertaining the effects of multiple components of acculturation on substance use and sexual behavior among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents primarily from Mexico (35%) and Cuba (31%). A sample of 302 adolescents (53% boys; mean age 14.51 years) from Miami (n = 152) and Los Angeles (n = 150) provided data on Hispanic and U.S. cultural practices, values, and identifications at baseline and provided reports of cigarette use, alcohol use, sexual activity, and unprotected sex approximately one year later. Results indicated strong gender differences, with the majority of significant findings emerging for boys. Supporting the immigrant paradox (i.e., that becoming oriented toward U.S. culture is predictive of increased health risks), individualist values predicted greater numbers of oral sex partners and unprotected sex occasions for boys. However, contrary to the immigrant paradox, for boys, both U.S. practices and U.S. identification predicted less heavy drinking, fewer oral and vaginal/anal sex partners, and less unprotected vaginal/anal sex. Ethnic identity (identification with one’s heritage culture) predicted greater numbers of sexual partners but negatively predicted unprotected sex. Results indicate a need for multidimensional, multi-domain models of acculturation and suggest that more work is needed to determine the most effective ways to culturally inform prevention programs.

Keywords: Acculturation, Hispanic, immigrant, adolescent, alcohol use, drug use, sexual behavior, unprotected sex

In the U.S., Hispanics suffer significant health disparities in substance use and HIV infection. Hispanics are 2.5 times more likely to contract HIV compared with non-Hispanic Whites (CDC, 2011); and Hispanic teenage girls are more likely than their White counterparts to contract sexually transmitted diseases and to become pregnant (CDC, 2011). Hispanic adolescents are also more likely than White adolescents to use nearly all classes of drugs (Johnston et al., 2011). The high school years are the time when many of these health disparities emerge (CDC, 2011).

These disparities are especially disconcerting given the size and growth rate of the Hispanic population. Hispanics currently account for 16% of the U.S. population (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011), representing a doubling of the Hispanic population since 1990; and by 2050, one-third of the entire U.S. population is projected to be of Hispanic descent. Hispanics are also a young population, with 40% under age 20 (Ennis et al., 2011). Thus, reducing health disparities in Hispanic youth is a wise investment in the reduction of future health care costs and critical to the future health of the United States (Hayes-Bautista, 2004).

Acculturation has been proposed as a possible explanation for these disparities. Acculturation refers to cultural adaptation that occurs following international migration, or as a result of growing up in an immigrant-headed household (Sam & Berry, 2010). Acculturation operates in domains such as language use, choice of friends and media, prioritization of self versus others, and ethnic and national identification (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010).

Among Hispanic adolescents, acculturation is predictive of cigarette smoking (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2011), alcohol use (Allen et al., 2008), and sexual behavior and risk taking (Guilamo-Ramos, Jaccard, Peña, & Goldberg, 2005). Hispanic adolescents are overrepresented among early drug and alcohol initiators (Johnston et al., 2011) and among adolescents initiating sex before age 15 or engaging in unprotected sex (CDC, 2011). However, the literature on links between acculturation and risk behaviors has been inconsistent (Lopez-Class, Castro, & Ramirez, 2011; Vega, Rodriguez, & Gruskin, 2009). This may be due to variations in conceptualizations and measurement of acculturation across studies (Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009), ranging from a single language-use item to multi-domain and multidimensional scales.

Conceptualizations of Acculturation

Some writers (e.g., Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister, Flórez, & Aguirre, 2006) have called for comprehensive models of acculturation including both (a) separate dimensions representing heritage and receiving cultural orientations and (b) multiple domains in which acculturation occurs. Schwartz, Unger, et al. (2010) proposed such a model, where heritage and receiving cultural streams (dimensions) are assumed to operate within the domains of practices, values, and identifications. We review these dimensions and domains here.

Dimensions of Acculturation

Many health-related studies have framed acculturation as a single linear dimension ranging from “completely oriented toward one’s heritage culture” to “completely oriented toward the culture of settlement” (Lopez-Class et al., 2011; Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009). Some studies have used proxy measures for acculturation, such as language spoken at home (Gordon-Larsen, Harris, Ward, & Popkin, 2003), immigrant generation (González Wahl & McNulty Eitle, 2010), and years spent in the U.S. (Gfroerer & Tan, 2003). All of these proxies assume that speaking English at home, having been born in the U.S., or having resided in the U.S. for longer amounts of time represent being “more acculturated,” defined as more American-like and less Hispanic-like in a perfect, zero-sum inverse relationship.

The cultural studies literature, however, has developed more nuanced and face-valid operationalizations of acculturation. Principally, this literature has inspired the development of bidimensional models where immigrants can acquire the practices and customs of the country in which they have settled without necessarily discarding the practices and customs of their cultural heritage (e.g., Guo, Suárez-Morales, Schwartz, & Szapocznik, 2009; Sam & Berry, 2010). Bidimensional models allow for biculturalism, where the person can simultaneously endorse both cultural streams. Although biculturalism is generally the most common and adaptive approach to acculturation (Sam & Berry, 2010), it is not captured within unidimensional models, suggesting that such models do not reflect the lived reality of immigrants.

Domains of Acculturation

Cultural practices refer to behaviors such as language use, media preferences, and choice of friends. Cultural values have often been represented by individualism and collectivism (Szapocznik, Scopetta, Aranalde, & Kurtines, 1978; Triandis, 1995) – which refers to the extent to which one values individual and group needs and desires. The individualism-collectivism dynamic is important given that the majority of immigrants to the U.S. and other individualistic Western nations originate from collectivist-oriented countries or regions (Steiner, 2009). Cultural identifications refer to ethnic and national identity – identifying with one’s heritage and receiving cultural groups (see Smith & Silva, 2011; and Schildkraut, 2011, for reviews of the ethnic and national identity literatures, respectively). As a multidimensional process, acculturation can occur differently in some domains than others. For example, immigrants to the U.S. may learn English but may not adopt individualist values or identify as American. Similarly, individuals who have lost (or never developed) fluency in their heritage languages may nonetheless identify with their cultures of origin (Portes & Rumbaut, 2006).

The distinction among practices, values, and identifications as domains of acculturation is important because each domain represents a different “approach” to the interface between heritage and U.S. cultural streams (Castillo & Caver, 2009). Cultural practices represent behavioral acculturation, in terms of the specific customs in which a person engages. Cultural values represent cognitive acculturation, in terms of beliefs that may or may not be compatible between the heritage and U.S. cultural streams. Cultural identifications represent affective acculturation, in terms of attachment to the U.S. and/or to one’s heritage country or region.

Acculturation and Health Risk Behaviors: Research Needs

A further question is whether the effects of acculturation on health risk behaviors (such as substance use and sexual activity) vary over the life course. In a sample of Hispanic immigrant college-attending emerging adults, Schwartz et al. (2011) found that the extent to which one retained one’s heritage-cultural practices and values was protective against illicit drug use and sexual risk taking. However, we do not know whether similar effects of cultural practices and values would also emerge for early and middle adolescents, whose normative developmental tasks and social contexts (e.g., compulsory school attendance in adolescence versus optional college attendance in emerging adulthood) are different from those of emerging adults, and for whom substance use and sexual behavior may carry greater developmental risk. The present study was designed to address this gap in the literature and to identify cultural mechanisms that can be used to help prevent cigarette, alcohol, and drug use, as well as and the adverse consequences of early and/or unprotected sexual behavior, among Hispanic early and middle adolescents (ages 14–16).

Need for Longitudinal Designs

The vast majority of acculturation-risk behavior studies have used cross-sectional designs where acculturation and health outcomes (e.g., substance use and sexual behavior) are measured at the same point in time (e.g., Allen et al., 2008; Ramirez et al., 2004). Although such studies are informative regarding links between cultural processes and risk behaviors, cross-sectional designs cannot provide evidence of directionality. Moreover, a number of longitudinal studies of adolescent acculturation patterns have been conducted recently (e.g., Knight et al., 2009), but longitudinal studies examining effects of adolescent acculturation on substance use and sexual behavior have been far less common (see Schwartz, Des Rosiers, et al., in press, for an example of such research).

Uncoupling Effects of Acculturation from Effects of Immigration Generation and Length of Stay

Zane and Mak (2003), among others, have suggested that acculturation may carry different meanings for recent immigrants, longer term immigrants, and later-generation (U.S.-born) individuals. Specifically, cultural adjustment is likely most acute during the first few years following immigration, whereas for longer term and later generation immigrants, acculturation may be focused more on balancing heritage-cultural influences with those from the receiving society (Fuligni, 2001). It might therefore be suggested that pooling participants across groups defined by qualitatively different degrees of exposure to the heritage and receiving cultural contexts may not provide accurate information in terms of links with risk behavior. For example, Guilamo-Ramos et al. (2005) found that, vis-à-vis early sexual debut, English-language use was protective for foreign-born Hispanics but risk-inducing for U.S.-born Hispanics. Pooling across immigrant generations in this case might have produced a weak or null result.

Need for Multisite Studies

Most studies examining the effects of acculturation on substance use and sexual activity and risk taking have utilized samples from a single geographic location. However, Hispanics are an extremely diverse group, in terms of national origin, socioeconomic status, history in the U.S., and other factors (Ennis et al., 2011). Receiving contexts may also exert important effects on acculturation and its effects on adolescent risk behaviors. The ways in which Hispanic immigrants adapt may differ markedly across various settings across the United States (e.g., Hayes-Bautista, 2004; Stepick, Grenier, Castro, & Dunn, 2003). It is therefore useful to sample from different receiving contexts when studying acculturation and its effects on Hispanic adolescent risk behavior.

The Present Study

This study examined the effects of acculturation on cigarette use, alcohol use, sexual behavior, and sexual risk taking in a sample of recently immigrated (5 years or less in the U.S. at baseline) Hispanic adolescents in Miami and Los Angeles. We address the limitations of past research in several ways. First, we utilized a multidimensional, multi-domain perspective on acculturation (Schwartz, Unger, et al., 2010). Second, we used a longitudinal design where acculturation processes were modeled as predictors of multiple risk behaviors over a 1-year span. Third, the use of a recent-immigrant adolescent sample allowed us to study the “critical period” for acculturation where (a) individuals are young enough to acquire a second cultural stream (Cheung, Chudek, & Heine, 2011) and (b) they arrived in the receiving context recently enough such that they are likely still undergoing considerable cultural change (Fuligni, 2001). Fourth, the inclusion of both Miami and Los Angeles as study sites allowed us to examine within-group patterns and differences as a function of geography/nationality/context of reception, although not to uncouple these effects from one another. Fifth, the availability of multiple domains of acculturation permitted us to examine the extent to which some aspects of heritage-culture retention may have been protective whereas others may have been risk-inducing (and likewise for U.S. culture acquisition).

Translating the immigrant paradox (where greater “acculturation” is linked with higher likelihood of risk behavior engagement) into a multidimensional, multi-domain view of acculturation, we expected that, in recent immigrant adolescents, heritage-cultural practices, values, and identifications would protect against involvement in cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and drunkenness, sexual activity, and sexual risk taking. U.S. practices, values, and identifications were expected to positively predict adolescent risk outcomes.

Method

Participants

The present analyses used baseline and one-year post-baseline adolescent-report data from a longitudinal study of acculturation among recently arrived Hispanic immigrant families (Schwartz, Unger, et al., 2012). The sample consisted of 302 adolescents from Miami (N = 152) and Los Angeles (N = 150). Baseline data were collected from May to November 2010, and the one-year post-baseline data were collected from September to December 2011.

Adolescents’ mean age at baseline was 14.51 years (SD = 0.88 years, range 14 to 17), and 53% were boys. Most adolescents in both Miami (83%) and Los Angeles (67%) arrived in the U.S. at the same time as their primary caregivers. As per inclusion criteria, all adolescents had arrived in the U.S. within five years of the time of data collection and were either finishing or going into the ninth grade. Adolescents in Miami had been in the U.S. for significantly less time (Mdn = 1 year, interquartile range = 0–3 years) than those in Los Angeles (Mdn = 3 years, interquartile range = 1–4 years), Wilcoxon Z = 6.39, p < .001. We therefore controlled for years in the U.S. in our analyses. We also controlled for parental education and adolescent age.

Miami participants were primarily from Cuba (61%), the Dominican Republic (8%), Nicaragua (7%), Honduras (6%), and Colombia (6%). Los Angeles participants were primarily from Mexico (70%), El Salvador (9%), and Guatemala (6%). The mean annual household income (self-reported by parents) was $30,854 (SD $10,824), somewhat lower than the median household income for U.S. Hispanic families in 2009 ($39,730; U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). In terms of parental education, 27% of parents reported less than nine years of education, 18% reported attending high school but not graduating, 33% reported receiving a high school degree, 12% reported attending college, and 10% reported having a bachelor’s degree or greater.

Procedure

For purposes of brevity, we provide a brief description of the study procedures here. A more detailed presentation can be found in Schwartz, Unger, et al. (2012). We randomly selected schools (in Miami-Dade County, which has only one school district) or school districts (in Los Angeles County, which has several) from which to recruit families. Because we were looking for recent-immigrant families, and given that many Hispanic immigrants tend to settle in heavily Hispanic areas (e.g., Stepick et al., 2003), we selected schools where the student body was at least 75% Hispanic. In total, 10 schools in Miami and 13 in Los Angeles participated in the study.

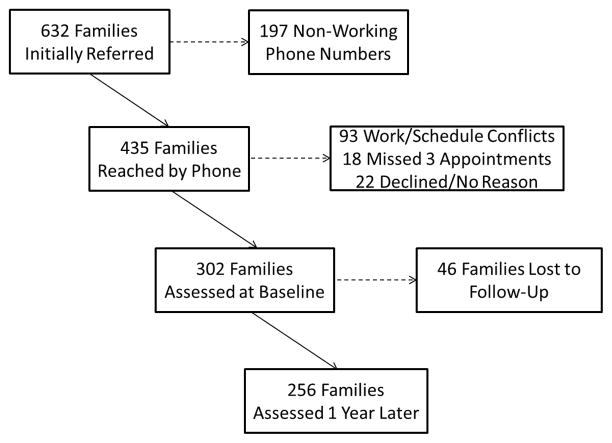

We gave a brief presentation about the study in English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) and other basic-level English classes. Interested students provided their parent’s or guardian’s phone number. Study staff then called each phone number and asked parents whether the adolescent had been in the U.S. for less than five years, and whether the family was planning to remain in the South Florida or Southern California areas during the four years of the study. For those families who met these inclusion criteria, we described the study and attempted to schedule evening or weekend informed consent and assessment appointments. We received contact information for 632 families who met the study’s inclusion criteria. Of these, 197 were unreachable, primarily because of incorrect or non-working telephone numbers. The remaining 435 families were reached by telephone and were pursued further for inclusion in the study. Of these 435 families, 69% (n = 302) participated (see Figure 1 for a flowchart of the assessment procedures). This recruitment rate was somewhat lower than the 83% that achieved by Guilamo-Ramos et al. (2009) in New York City. Each parent received $40, and each adolescent received a voucher for a movie ticket (valued at $10), for their participation. The retention rate at 1 year post-baseline was 85%, and parents were paid $50 for participation at 1 year post-baseline.

Figure 1.

Assessment Flowchart – COPAL, Miami/Los Angeles, 2010–2011

Prior to beginning the assessments, the primary caregiver within each family was asked to provide informed consent for her/himself and the adolescent to participate, and adolescents were asked to provide informed assent. Adolescents completed assessments on laptop computers, and parents completed assessments on touch-screen tablet computers. Each participant completed the assessment battery using an audio computer-assisted interviewing (A-CASI) system (Cooley et al., 2003). The majority of adolescents completed their assessments in Spanish at baseline (84%) and at 1 year post-baseline (72%).

Measures

Acculturation

Consistent with Schwartz et al. (2010), acculturation was assessed in terms of heritage and U.S. practices, values, and identifications. As noted above, the heritage and U.S. cultural streams (dimensions) are assumed to operate within each of the three domains.

Cultural practices were assessed using the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire-Short Version (BIQ-S; Guo et al., 2009). The BIQ-S consists of 24 items, 12 assessing U.S. practices (e.g., speaking English, eating American food, associating with American friends), and 12 about Hispanic practices (e.g., speaking Spanish, eating Hispanic food, associating with Hispanic friends). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were .91 for U.S. practices and .89 for Hispanic practices. A five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), was used.

We measured cultural values in terms of individualism-collectivism (Triandis, 1995). Individualism refers to prioritizing one’s own needs and desires over those of family or other social groups, whereas collectivism represents prioritizing the needs and desires of others –including family members – over one’s own needs and desires.). Individualism and collectivism were assessed using subscales developed by Triandis and Gelfand (1998). A five-point Likert Scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree) was used. Alpha coefficients were .73 for individualism and .79 for collectivism.

Ethnic and U.S. identifications were assessed using the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts et al., 1999) and the American Identity Measure (Schwartz, Park, et al., 2012). The American Identity Measure was adapted from the MEIM, with “the U.S.” inserted in place of “my ethnic group”. Cronbach’s alphas were .88 for U.S. identity and .91 for ethnic identity.

Cigarette, Alcohol, and Illicit Drug Use

We assessed cigarette, alcohol, and illicit drug use using a modified version of the Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston et al., 2011). We asked about frequency of cigarette use, alcohol use, heavy drinking (largest number of drinks consumed in a day), drunkenness, and use of illicit drugs in the participant’s lifetime, in the 90 days prior to assessment, and in the 30 days prior to assessment. Because illicit drug use was reported only by 8 adolescents, we were not able to include this outcome in our analyses. Moreover, although it is most common to analyze substance use in the 30 days prior to assessment (Johnston et al., 2011), base rates were low – so we analyzed cigarette and alcohol outcomes in the 90 days prior to the Time 2 assessment (for which base rates were higher). For each substance use behavior, adolescents were asked to type in the number corresponding to how many times they had engaged in that behavior during the 90 days prior to assessment. Our substance use outcomes therefore included whether or not adolescents had smoked cigarettes, how many times they had drunk alcohol, the maximum number of drinks they had consumed in a single day, and the number of times they had been drunk in the 90 days prior to assessment.

Sexual Risk Taking

We asked each participant how many times in the last 90 days she or he had engaged in a number of sexual behaviors. Because many young people engage in oral sex without intercourse (Lindberg, Jones, & Santelli, 2008), we asked separately about number of oral sex partners and about number of vaginal/anal sex partners. For each of these items, participants were asked to type in the number of partners during the past 90 days. We also asked participants how often they used a condom during oral, vaginal, or anal sex during the past 90 days. The response scale for both of these items ranged from 0 (Never) to 4 (Always). We summed the responses to these two items to create a total score for unprotected sex.

Data Analytic Strategy

The present analyses were conducted in three general steps. First, for descriptive purposes, we compared the acculturation indices at baseline, and the health risk behaviors at 1 year post-baseline, across site and across gender. Significant site or gender differences would necessitate that we conduct the analyses in multigroup form, with site or gender as the grouping variable. Second, we examined bivariate correlations among the acculturation indices to ensure that these indices were sufficiently independent to include as separate predictor variables. Third, within a single structural equation model, we regressed each of the individual risk behavior variables on Hispanic and U.S. practices, individualist and collectivist values, and U.S. and ethnic identity. The predictor variables were kept separate to permit us to evaluate the contributions of each of the hypothesized acculturation processes (Schwartz et al., 2010). Using a single model avoids “multiple testing” concerns inherent in conducting separate multiple regression models for each outcome. Standard model fit indices are not available for models with count variables.

We included site, age, years in the U.S., and parental education as covariates in the structural equation model. The sandwich covariance estimator (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001) was used to control for nesting of participants within schools. We did not control for prior levels of the risky behaviors, because categorical or count variables are likely less sensitive to change than continuous variables are – and large autocorrelations may therefore prevent predictive effects from emerging (Agresti, 2007).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations among Acculturation Indices

Means and standard deviations for the acculturation variables at baseline are provided in Table 1. Frequencies for the cigarette, alcohol, and sexual variables at 1 year post-baseline are also reported in Table 1. Other than U.S. practices, all of the domains of acculturation were endorsed more strongly at baseline by Miami adolescents than by Los Angeles adolescents. At 1 year post-baseline, cigarette and alcohol use were reported slightly (but not significantly) more in Los Angeles, and sexual behavior and risk taking were reported significantly more in Miami.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Variable | Miami | Los Angeles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variables at Baseline | |||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | t-value | |

| U.S. practices | 46.43 (16.23) | 48.82 (16.14) | 1.29 |

| Hispanic Practices | 59.48 (13.83) | 54.15 (15.77) | 3.12** |

| Individualist Values | 20.78 (4.77) | 18.60 (4.81) | 3.96*** |

| Collectivist Values | 25.68 (3.85) | 23.23 (3.93) | 5.48** |

| U.S. identity | 28.57 (8.05) | 25.48 (8.38) | 3.26** |

| Ethnic Identity | 33.22 (7.85) | 30.79 (7.82) | 2.70** |

| Risk Behaviors at 1 Year Post-Baseline | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | χ2 | |

| Substance Use (Last 90 Days) | |||

| Cigarette Smoking | 7 (4.6%) | 9 (6.0%) | 0.46 |

| Any Alcohol Use | 14 (9.9%) | 21 (18.3%) | 3.05 |

| 5+ Drinks in a Day | 8 (5.4%) | 10 (8.7%) | 0.51 |

| Drunk At Least Once | 10 (7.1%) | 11 (9.6%) | 0.24 |

| Sexual Behavior (Last 90 Days) | |||

| Initiated sex (lifetime) | 50 (35.5%) | 26 (22.6%) | 4.42* |

| Any oral/anal/vaginal sex | 34 (24.1%) | 12 (10.4%) | 7.14** |

| Unprotected vaginal/anal sex | 20 (9.9%) | 6 (5.2%) | 4.64* |

| Unprotected oral sex | 16 (11.3%) | 4 (3.5%) | 4.41* |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Intercorrelations among the acculturation indices were generally modest. Among the U.S. acculturation indices, U.S. practices were significantly related to U.S. identity, r = .47, p < .001, but only weakly related to individualist values, r = .11, p = .05; and individualist values were significantly related to U.S. identity, r = .24, p < .002. The Hispanic acculturation indices were all significantly interrelated: Hispanic practices with collectivist values, r = .27, p < .001; Hispanic practices with ethnic identity, r = .28, p < .001; and collectivist values with ethnic identity, r = .45, p < .001. Corresponding U.S. and Hispanic acculturation indices were modestly interrelated in all three domains: U.S. and Hispanic practices, r = −.33, p < .001; individualist and collectivist values, r = .21, p < .001; U.S. and ethnic identity, r = .22, p < .002.

Acculturation as a Predictor of Substance Use and Sexual Behavior

We next examined the six domains of acculturation at baseline as predictors of substance use and sexual activity at 1 year post-baseline. To determine whether we would need to estimate separate models for the Miami and Los Angeles sites, we conducted an invariance test by comparing the fit of a model with all paths free to vary across sites against a model with all paths constrained equal across sites. Although standard model fit statistics are not available in models with count variables, a chi-square difference test can be conducted by doubling the difference between the log-likelihood values for the constrained and unconstrained models (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Results of the invariance test indicated that the model results did not differ significantly across sites, Δχ2 (80) = 94.65, p = .13, so we collapsed the sample across sites for analysis. However, the model did not fit equivalently across gender, Δχ2 (72) = 398.51, p < .001. As a result, we estimated the model in multigroup form, separately by gender. For purposes of simplicity, we present the results separately for substance use outcomes and for sexual behavior outcomes. Because of the fairly low base rates for many of the risk behaviors, findings significant at p < .10 are flagged in Table 2 as approaching significance. However, references to significant results include only those for which p < .05.

Table 2.

Effects of Acculturation on Health Risk Behaviors

| Outcome | U.S. Practices | Hispanic Practices | Individualist Values | Collectivist Values | U.S. Identity | Ethnic Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR/IRR (95% CI) | OR/IRR (95% CI) | OR/IRR (95% CI) | OR/IRR (95% CI) | OR/IRR (95% CI) | OR/IRR (95% CI) | |

| Cigarette Smoking | ||||||

| Boys | 0.49 (0.03–7.67) | 0.31 (0.06–1.72) | 2.58 (0.32–20.67) | 2.87* (1.05–7.83) | 0.43 (0.13–1.51) | 0.45 (0.16–1.25) |

| Girls | 0.85 (0.33–2.18) | 0.83 (0.31–2.18) | 3.23§ (0.97–10.74) | 0.31* (0.13–0.78) | 0.71 (0.32–1.55) | 2.05 (0.45–9.35) |

| Alcohol Use Occasions | ||||||

| Boys | 1.30* (1.03–1.64) | 5.67*** (2.92–11.02) | 0.64*** (0.58–0.70) | 2.09*** (1.48–2.94) | 0.96 (0.65–1.46) | 0.29*** (0.23–0.37) |

| Girls | 1.65** (1.23–2.22) | 1.04 (0.49–2.19) | 1.42§ (1.00–2.01) | 1.12 (0.72–1.76) | 0.98 (0.74–1.31) | 1.46§ (0.97–2.19) |

| Maximum Drinks/Day | ||||||

| Boys | 1.08 (0.77–1.51) | 4.60*** (2.44–8.66) | 0.60*** (0.52–0.69) | 0.19*** (0.18–0.20) | 0.40*** (0.36–0.44) | 2.67*** (1.53–4.65) |

| Girls | 2.22** (1.23–4.02) | 1.30 (0.80–2.12) | 0.79§ (0.60–1.03) | 0.29*** (0.18–0.47) | 0.36*** (0.21–0.61) | 3.22*** (2.21–4.69) |

| Number of Sexual Partners | ||||||

| Boys | 1.10 (0.76–1.60) | 0.64** (0.47–0.87) | 0.92 (0.62–1.35) | 0.57* (0.37–0.88) | 0.52** (0.35–0.78) | 1.34 (0.52–3.39) |

| Girls | 1.87§ (0.92–3.81) | 0.87 (0.69–1.10) | 1.22 (0.84–1.78) | 1.26 (0.79–1.99) | 0.48* (0.25–0.92) | 0.84 (0.62–1.13) |

| Number of Oral Sex Partners | ||||||

| Boys | 0.55* (0.31–0.97) | 0.47** (0.29–0.77) | 4.02*** (3.04–5.31) | 1.17 (0.62–2.19) | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 1.57* (1.11–2.22) |

| Girls | 1.54 (0.51–4.64) | 1.20 (0.71–2.04) | 1.26 (0.77–2.08) | 1.17 (0.63–2.17) | 0.86 (0.33–2.23) | 0.84 (0.55–1.30) |

| Frequency Unprotected Sex | ||||||

| Boys | 0.71*** (0.59–0.85) | 1.21 (0.96–1.51) | 1.59 (0.86–2.94) | 1.61 (0.91–2.83) | 0.65§ (0.39–1.06) | 0.51*** (0.35–0.73) |

| Girls | 0.21*** (0.09–0.40) | 0.33§ (0.10–1.04) | 1.08 (0.74–1.60) | 1.40 (0.64–3.02) | 8.79** (1.90–40.72) | 0.77 (0.31–1.86) |

Note: All coefficients presented are controlled for age, parent education, years in the United States, and site.

No significant predictors emerged for binge drinking or drunkenness for either gender.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Substance Use Outcomes

The pattern of results for substance use appears to suggest a complex interaction among acculturation components, gender, and specific risk outcomes. With regard to cigarette smoking and to frequency of alcohol use, heavy drinking, binge drinking, and drunkenness, the majority (11 of 17) of significant results emerged for boys. U.S. practices were risk-inducing vis-à-vis alcohol use occasions for both genders, and vis-à-vis heavy drinking only for girls. Hispanic practices were risk-enhancing for frequency of alcohol use and for heavy drinking for boys only. Individualist values were protective against alcohol use occasions and against heavy drinking for boys, but for girls, individualist values approached significance as risks for cigarette smoking and for more frequent alcohol use. Collectivist values were risk-enhancing for cigarette smoking among boys but protective for girls; collectivist values were protective against heavy drinking for both genders; and collectivist values were risk-enhancing vis-à-vis alcohol use occasions for boys. Both boys and girls identifying with the United States to greater degrees were less likely to engage in heavy drinking. Ethnic identity was risk-enhancing with regard to heavy drinking for both genders and approached significance as a risk factor for occasions of alcohol use among girls. For boys, ethnic identity was protective against occasions of alcohol use.

Sexual Outcomes

Results for sexual outcomes again suggested a complex interaction among acculturation components, gender, and specific domains of risk. The majority (9 of 12) of significant effects for sexual outcomes emerged for boys. U.S. practices were protective against unprotected sex for both genders, and against number of oral sex partners for boys only. U.S. practices approached significance as risk-enhancing for number of sexual partners among girls. Hispanic practices were associated with fewer sexual partners and oral sex partners for boys, and approached significance as protective against unprotected sex for girls. For boys only, individualist values were risk-enhancing vis-à-vis number of oral sex partners, and collectivist values were associated with fewer sexual partners. Identifying with the U.S. was protective against number of sexual partners for both genders, and served as a risk for unprotected sex among girls (and approached significance as protective against unprotected sex for boys). Among boys only, ethnic identity was predictive of greater numbers of oral-sex partners but was protective against unprotected sex.

Discussion

The present study was designed to examine the effects of an expanded set of acculturation processes on multiple risk behaviors, including cigarette smoking, alcohol-related behaviors, and sexual activity and risk taking in a multisite study among a diverse group of Hispanics. We utilized a sample of recent immigrants who were most likely to be undergoing cultural adjustment. Following recent recommendations (Abraído-Lanza et al., 2006; Fuligni, 2001), we employed a longitudinal design and examined multiple domains and dimensions of acculturation as predictors of adolescent risk outcomes. We also employed a multisite design as a way of increasing generalizability of our findings.

Among the most general patterns of findings was that the effects of acculturation on risk behaviors varied across gender, and that different domains within the same dimension of acculturation often exerted opposing effects on risk behavior engagement. For example, among boys, collectivist values were protective against heavy drinking, but Hispanic practices and ethnic identity were risk-enhancing vis-à-vis heavy drinking. In this case, within gender, one domain (values) appeared to support the immigrant paradox, whereas the others (practices and identifications) did not. These findings underscore the need to utilize multidimensional understandings of acculturation vis-à-vis health risk behaviors. Further, our findings suggest that the functions of acculturation vis-à-vis risk behaviors may be gendered (Smith, 2006). As a result, culturally informed preventive efforts should draw upon multiple dimensions and domains of acculturation and should be adapted differently for boys and girls, as discussed further below.

Among girls, U.S. practices were positively predictive of cigarette smoking, and U.S. identity was positively predictive of unprotected sex; among boys, individualist values were positively predictive of oral-sexual promiscuity; and for both genders, U.S. practices were positively predictive of alcohol use occasions. These findings would be expected given the immigrant paradox. However, a number of findings counter to the paradox also emerged. First, U.S. practices and individualist values were not universally risk-enhancing: among boys, U.S. practices were protective against number of oral-sex partners and against unprotected sex, and individualist values were protective against alcohol use and against heavy drinking. Second, all but one of the effects of U.S. identification were protective, including significant findings for heavy drinking and sexual promiscuity for both genders. Third, ethnic identity – which is assumed to be universally protective – was protective against alcohol use and unprotected sex, but positively predictive of heavy drinking and number of oral-sex partners, among boys. This latter finding is inconsistent with much of the literature on ethnic identity (e.g., Marsiglia, Kulis, Hecht, & Sills, 2004). However, the finding for ethnic identity and number of oral sex partners is consistent with results obtained on other Hispanic samples where both cultural practices and identifications were included as predictors (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2011). What this suggests is that at least some of the protective effect of ethnic identity against sexual risk taking involves engagement in cultural behaviors. Indeed, Syed et al. (in press) found that, among ethnic minority college students, participation in ethnic behaviors, but not thinking about ethnic issues, was associated with well-being.

Importantly, effects of acculturation on cigarette use, alcohol use, and sexual activity were consistent across Miami and Los Angeles – two very different contexts of reception with very different Hispanic subgroups (primarily Cuban versus primarily Mexican). Although there is considerable diversity among Hispanics, our results suggest that the functions of acculturation –vis-à-vis adolescent risk behaviors – are consistent across at least some Hispanic groups. These results suggest that similar acculturative processes may serve as intervention targets for Hispanics across national origins and regions of settlement.

Consistency of the Present Results with the Immigrant Paradox

With regard to Hispanic immigrants, U.S. culture is often thought of as associated with unhealthy lifestyles (Aguirre-Molina, Borell, & Vega, 2010), including drug and alcohol use and sexual promiscuity. On the other hand, retaining Hispanic culture is thought of as protective against these outcomes (Unger & Schwartz, 2012). The present findings suggest that the picture is more complex. Contrary to the immigrant paradox hypothesis, when we split the sample by gender, less than half (12 of 27) of the significant associations that we found involved U.S. acculturation, and less than half (5 of 12) of these U.S.-acculturation effects were risk-inducing. The predictive effects of Hispanic cultural orientation were also equivocal: 8 were protective and 7 were risk-inducing. For practices and values, almost half (4 of 9) of the significant effects of U.S. cultural orientations are risk-inducing and the majority (6 of 10) of the significant effects of Hispanic cultural orientations are protective. However, for identifications, 3 of the 5 significant effects of Hispanic cultural orientations are risk-inducing and 4 of the 5 significant effects of U.S. cultural orientations are protective. This pattern suggests that, somewhat consistent with the immigrant paradox, retaining Hispanic behaviors and collectivist values may be important to balance the effects of acquiring U.S. practices and individualist values on initiation of cigarette smoking, underage drinking, and risky sexual behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Interestingly, there were fewer significant effects of acculturation on risky behavior for girls – possibly because girls engaged in less risky behavior than boys did.

However, focusing solely on cultural practices, as many studies have done, may have led to potentially mistaken support for the immigrant paradox hypothesis (given that U.S. practices were positively associated with a number of risky drinking and sexual behaviors). In contrast, findings for cultural identifications are largely opposed to the immigrant paradox. Ethnic identity was positively predictive of oral sex (but protective against unprotected sex) for boys. For both genders, U.S. identity was protective against heavy drinking and sexual promiscuity, and U.S. identity approached significance as protective against unprotected sex for boys. The only risk-enhancing effect involving U.S. identity was for unprotected sex among girls. Summarizing the pattern of results for cultural identifications, one might assume that identifying with the U.S. is largely protective, whereas identifying with one’s ethnicity or country of origin may be somewhat risk-enhancing. Identifying with one’s country of residence is linked with positive adjustment (Schwartz, Waterman, et al., in press) and may indicate “fitting in” with the receiving culture, whereas continuing to identify as a member of another country (e.g., “I am Mexican” or “I am Cuban”) may represent somewhat of a defensive response (Rumbaut, 2008). Promoting identification with the U.S., perhaps as a way to encourage biculturalism, may represent an important component of acculturation-based interventions.

It may be important to qualify the role of U.S. cultural orientation in alcohol use. U.S. practices did appear to serve as risks for heavy drinking and drunkenness for girls, and individualist values approached significance as risks for alcohol use (for both genders) and for heavy drinking and drunkenness (for girls). Alcohol use is indeed encouraged by Americanized peers (Prado et al., 2009), but alcohol use is also prominent in many Hispanic cultures. For example, machismo and marianismo – which represent strongly differentiated gender roles – are an integral component of many Hispanic cultural streams (Aguirre-Molina et al., 2010). These value systems may be associated with alcohol use (Arciniega, Anderson, Tovar-Blank, & Tracey, 2008). Some Hispanic males may drink alcohol as a way of expressing their masculinity, and some Hispanic females may do so to please their male friends or partners.

Although our results can speak to the immigrant paradox from a short-term perspective, some aspects of the immigrant paradox must be investigated using longer-term studies. For example, epidemiological research has found that immigrants’ mental and physical health worsens with increasing exposure to U.S. culture and with successive generations in the United States (Franzini, Ribble, & Keddie, 2001). Acculturation, measured unidimensionally where increasing U.S. orientation is equated with loss of Hispanic cultural orientation, is often implicated as a cause of the paradox (e.g., Gordon-Larsen et al., 2003). However, as Schwartz, Unger, et al. (2010) have argued, a more ecologically valid, multidimensional perspective on acculturation may not map so neatly onto the immigrant paradox. For example, a bidimensional perspective allows for decoupling of U.S. culture acquisition from heritage culture retention. Such decoupling would provide an opportunity to examine whether the observed deteriorations in health indices are associated with adoption of U.S. culture, with loss of Hispanic culture, or both. Further, given the simplistic models of acculturation often employed in public health research, it is unclear which domain(s) of acculturation might be most closely linked with the immigrant paradox. Further research is necessary to examine these issues.

Limitations

The present results should be interpreted in light of at least two important limitations. First, our recruitment efforts appeared to be more successful in Miami than in Los Angeles, such that the Los Angeles sample may be less representative of the Los Angeles Hispanic immigrant adolescent population. This difference in recruitment success rates across the two cities may have been due to differential legal status between Cuban and Mexican immigrants. Cuban immigrants become legal U.S. residents as soon as they set foot on American soil (and therefore they cannot be undocumented) and have access to a series of resources and services that are not available for those who are undocumented. On the other hand, nearly half of the Mexican immigrant population in the U.S. is undocumented (Ennis et al., 2011). Anecdotal evidence from our assessment teams suggests that many Los Angeles families were afraid of our assessors and expressed fear that our staff were government officials attempting to deport them. We experienced some of these reactions with Central American families in Miami, but the predominance of Cubans likely increased the success of our engagement efforts in Miami.

Second, we obtained information on substance use and sexual activity via self-reports. Although the audio computer-assisted data collection system has shown to increase the veracity of self-reported data (Cooley et al., 2003), future studies should obtain biological indicators (e.g., urine samples) of drug use. Moreover, collateral reports of sexual activity would help to correct for potential overreporting or underreporting of sexual behaviors.

Third, it is worth noting that our sample consisted of recent immigrants, who represent only a small segment of the Hispanic adolescent population (Vega et al., 2009). Given that recent immigrants, long-term immigrants, and second-generation immigrants represent distinct groups (Zane & Mak, 2003), it is essential to replicate the present results with long-term and second-generation immigrants. Such replications would provide critical information regarding how acculturation-based interventions might be designed and delivered differently depending on adolescents’ nativity or length of stay in the United States. Further, the adolescents in our study were undergoing multiple transitions, including having recently immigrated and entering high school. We do not know the extent to which other life transitions, in addition to immigration, might have affected the present results.

Conclusions and Implications for Preventive Interventions

Despite these and other potential limitations, the present study has provided evidence regarding longitudinal effects of multiple dimensions of acculturation on substance use and sexual activity among recently immigrated Hispanic adolescents in two large American cities. The consistency of the predictive links between acculturation and risk behaviors across cities suggests that intervention activities and programs targeting acculturation (e.g., Smokowski & Bacallao, 2011) might be delivered similarly to different Hispanic populations and in different areas of the U.S. Further, whereas much of the acculturation literature has focused on cultural practices, our results suggest that cultural identifications – particularly identification with the U.S. – may be protective against a range of risk behaviors and should be targeted within intervention activities (see Smokowski & Bacallao, 2011, for an example of methods to promote biculturalism and heritage-culture retention).

Acculturation-Based Prevention Interventions

Although a number of culturally informed preventive interventions have been designed and evaluated (see Prado, Szapocznik, Maldonado-Molina, Schwartz, & Pantin, 2008, for a review), these programs have not explicitly targeted components of acculturation. Only two acculturation-based prevention programs, Bicultural Effectiveness Training (Szapocznik et al., 1986) and Entre Dos Mundos (Between Two Worlds; Smokowski & Bacallao, 2011), have been introduced into the published literature. Both of these interventions aim to promote biculturalism – endorsement of both Hispanic and U.S. cultural streams – in adolescents and their parents. In terms of the acculturation domains, both of these programs focus primarily on cultural practices and have been evaluated largely in terms of changes in cultural practices. Results of a randomized trial with Hispanic immigrant families in Miami indicated that Bicultural Effectiveness Training resulted not only in increased Hispanic and U.S. practices among adolescents, but also in improved reports of family functioning and reductions in adolescent behavior problems (Szapocznik et al., 1986). To our knowledge, Entre Dos Mundos has not yet been evaluated in a randomized trial.

Adding cultural values and identifications creates a great deal of complexity, where different domains within the same acculturation dimension can exert opposing effects on substance use and sexual behavior. Although this complexity is likely to prove challenging for intervention development, the ecological validity of an expanded model of acculturation suggests that intervention efforts based on such a model have the potential to impact culturally based risk and protective factors for Hispanic adolescent substance use and sexual behavior. For example, encouraging identification with the United States – perhaps through discussions of why adolescents and their families immigrated and the opportunities that this immigration may provide – may increase protection against heavy drinking and early sexual debut for boys. At the same time, however, U.S. practices – reflecting behaviors associated with “acting American” –may place girls at risk for heavy drinking and early sexual debut. The nuances among the three domains of acculturation – particularly between practices and identifications – will need to be fleshed out in order for acculturation-based preventive interventions to be maximally efficacious.

In conclusion, our results strongly suggest that the conceptualization and measurement of acculturation is not simply a theoretical argument – rather, the ways in which acculturation is defined and measured may have important public health implications (Lopez-Class et al., 2011; Thomson & Hoffman-Goetz, 2009) as well as implications for the development of public health policies and campaigns. We hope that the present results will help to open a new line of ecologically valid research on the role of acculturation in preventing risky behavior among Hispanic adolescents.

Acknowledgments

The study on which this article is based was supported by Grant DA025694, co-funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse. We thank Dr. Judy Arroyo for her helpful feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

All authors contributed substantially to the study and to this article. Seth J. Schwartz and Jennifer B. Unger served as Co-Principal Investigators, oversaw the conduct of the study, and participated in manuscript preparation; Sabrina E. Des Rosiers scored and cleaned the data and participated in manuscript preparation; Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco and Byron L. Zamboanga participated in manuscript preparation; Shi Huang conducted the data analyses; Juan A. Villamar, Daniel W. Soto, and Monica Pattarroyo managed the data collection efforts; and Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati and José Szapocznik served as senior cultural advisors and participated in manuscript preparation.

References

- Abraído-Lanza AF, Armbrister AN, Flórez KR, Aguirre AN. Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1342–1346. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Molina M, Borrell LN, Vega WA, editors. Health issues in Latino males: A social structural approach. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allen ML, Elliott MN, Fuligni AJ, Morales LS, Hambarsoomian K, Schuster MA. The relationship between Spanish language use and substance use behaviors among Latino youth: A social network approach. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, Tracey TJG. Toward a fuller conceptualization of machismo: Development of traditional machismo and caballerismo scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Caver K. Expanding the concept of acculturation in Mexican American rehabilitation psychology research and practice. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2009;54:351–362. doi: 10.1037/a0017801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Latinos. 2011 Retrieved March 6, 2013 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/latinos/index.htm.

- Cheung BY, Chudek M, Heine SJ. Evidence for a sensitive period for acculturation: Younger immigrants report acculturating at a faster rate. Psychological Science. 2011;22:147–152. doi: 10.1177/0956797610394661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley PC, Rogers SM, Turner CF, Al-Tayyib AA, Willis G, Ganapathi L. Using touch screen audio-CASI to obtain data on sensitive topics. Computers in Human Behavior. 2001;17:285–293. doi: 10.1016/S0747-5632(01)00005-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Rios-Vargas M, Albert NG. The Hispanic population, 2010 (Census brief C2010BR-4) Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. A comparative longitudinal approach to acculturation among children from immigrant families. Harvard Educational Review. 2001;71:566–578. [Google Scholar]

- Gfroerer JC, Tan LL. Substance use among foreign-born youths in the United States: Does the length of residence matter? American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1892–1895. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;162:267–278. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González Wahl A, McNulty Eitle T. Gender, acculturation, and alcohol use among Latina/o adolescents: A multi-ethnic comparison. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2010;12:153–165. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9179-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, Harris KM, Ward DS, Popkin BM. Acculturation and overweight-related behaviors among Hispanic immigrants to the US: the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:2023–2034. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Jaccard J, Lesesne CA, Gonzalez B, Kalogerogiannis K. Family mediators of acculturation and adolescent sexual behavior in Latino youth. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:395–419. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Jaccard J, Peña J, Goldberg V. Acculturation-related variables, sexual initiation, and subsequent sexual Behavior among Puerto Rican, Mexican, and Cuban Youth. Health Psychology. 2005;24:88–95. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Suarez-Morales L, Schwartz SJ, Szapocznik J. Some evidence for multidimensional biculturalism: Confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance analysis on the Bicultural Involvement Questionnaire-Short Version. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:22–31. doi: 10.1037/a0014495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Bautista D. La Nueva California: Latinos in the Golden State. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Volume I, Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kauerman G, Carroll RJ. A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:1387–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Vargas-Chanes D, Losoya SH, Cota-Robles S, Chassin L, Lee JM. Acculturation and enculturation trajectories among Mexican American adolescent offenders. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:625–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg LD, Jones R, Santelli JS. Noncoital sexual activities among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Class M, Castro FG, Ramirez AG. Conceptions of acculturation: A review and statement of critical issues. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;72:1555–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among U.S. Hispanic youth: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML, Sills S. Ethnicity and ethnic identity as predictors of drug norms and drug use among pre-adolescents in the Southwest. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39:1061–1094. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide, version 5. Los Angeles: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America: A portrait. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Huang S, Schwartz SJ, Maldonado-Molina M, Bandiera FC, de la Rosa M, Pantin H. What accounts for differences in substance use among U.S. born and immigrant Hispanic adolescents? Results from a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Szapocznik J, Maldonado-Molina MM, Schwartz SJ, Pantin H. Drug abuse prevalence, etiology, prevention, and treatment in Hispanic adolescents: A cultural perspective. Journal of Drug Issues. 2009;38:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero AJ. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Sam DL, Berry JW. Acculturation: When individuals and groups of different cultural backgrounds meet. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2010;5:472–481. doi: 10.1177/1745691610373075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildkraut D. National identity in the United States. In: Schwartz SJ, Luyckx K, Vignoles VL, editors. Handbook of identity theory and research. New York: Springer; 2011. pp. 845–866. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Des Rosiers SE, Huang S, Zamboanga BL, Unger JB, Knight GP, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Developmental trajectories of acculturation in Hispanic adolescents: Associations with family functioning and adolescent risk behavior. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12047. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Waterman AS, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, Kim SY, Vazsonyi AT, Williams MK. Acculturation and well-being among college students from immigrant families. Journal of Clinical Psychology. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21847. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Weisskirch R, Zamboanga BL, Castillo LG, Ham L, Huynh Q, Cano MA. Dimensions of acculturation: Associations with health risk behaviors among college students from immigrant families. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:27–41. doi: 10.1037/a0021356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RC. Mexican New York: Transnational lives of new immigrants. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, Silva L. Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:42–60. doi: 10.1037/a0021528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Bacallao ML. Becoming bicultural: Risk, resilience, and Latino youth. New York: New York University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner N. International migration and citizenship today. New York: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stepick A, Grenier G, Castro M, Dunn M. This land is our land: Immigrants and power in Miami. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Walker LHM, Lee RM, Armenta BE, Huynh Q-L, Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL. A two-factor model of ethnic identity exploration: Implications for identity coherence and well-being. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0030564. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Santisteban D, Rio A, Perez-Vidal A, Kurtines WM, Hervis OE. Bicultural effectiveness training (BET): An intervention modality for families experiencing intergenerational/intercultural conflict. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1986;6:303–330. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Scopetta M, Aranalde MD, Kurtines WM. Cuban value structure: Treatment implications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:961–970. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: A systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, Gelfand MJ. Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:118–128. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Money income of families – median income by race and Hispanic origin in current and constant (2009) dollars, 1990–2009. 2012 Retrieved August 1, 2012 from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/income_expenditures_poverty_wealth.html.

- Unger JB, Schwartz SJ. Measuring cultural influences: Quantitative approaches. Preventive Medicine. 2012;55:353–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, Gruskin E. Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009;31:99–112. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane N, Mak W. Major approaches to the measurement of acculturation among ethnic minority populations: A content analysis and an alternative empirical strategy. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 39–60. [Google Scholar]