Abstract

Background

The Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) rating scale is an English-language instrument used worldwide to assess functional evaluation of patients with musculoskeletal cancer. Despite its use in several studies in English-speaking countries, its validity for assessing patients in other languages is unknown. The translation and validation of widely used scales can facilitate the comparison across international patient samples.

Objectives/purposes

The objectives of this study were (1) to translate and culturally adapt the MSTS rating scale for functional evaluation in patients with lower extremity bone sarcomas to Brazilian Portuguese; (2) analyze its factor structure; and (3) test the reliability and (4) validity of this instrument.

Method

The MSTS rating scale for lower limbs was translated from English into Brazilian Portuguese. Translations were synthesized, translated back into English, and reviewed by a multidisciplinary committee for further implementation. The questionnaire was administered to 67 patients treated for malignant lower extremity bone tumors who were submitted to limb salvage surgery or amputation. They also completed a Brazilian version of the Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS). Psychometric properties were analyzed including factor structure analysis, internal consistency, interobserver reliability, test-retest reliability, and construct validity (by comparing the adapted MSTS with TESS and discriminant validity).

Results

The MSTS rating scale for lower limbs was translated and culturally adapted to Brazilian Portuguese. The MSTS-BR proved to be adequate with only one latent dimension. The scale was also found to be reliable in a population that speaks Brazilian Portuguese showing good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) and reliability (test-retest reliability and interobserver agreement of 0.92 and 0.98, respectively). Validity of the Brazilian MSTS rating scale was proved by moderate with TESS and good discriminant validity.

Conclusions

The Brazilian version of the MSTS rating scale was translated and validated. It is a reliable tool to assess functional outcome in patients with lower extremity bone sarcomas. It can be used for functional evaluation of Brazilian patients and crosscultural comparisons.

Introduction

With advances in chemotherapy and surgical techniques for treating musculoskeletal cancer, much of the focus on treatment has now shifted to the improvement of postsurgical functional evaluation in patients with lower extremity sarcoma. These patients experience significant physical disability as a consequence of their disease and treatment [17]. However, given the relatively low prevalence of these tumors, it is rare that individual institutions or even entire countries can achieve the required samples sizes to adequately evaluate treatment efficacy. Thus, there is a need to use brief, standardized, and psychometrically robust health status questionnaires for this purpose [3]. Unfortunately, most scales evaluating disability have not been crossculturally validated to allow for multinational prospective studies. To assess comparability of results, researchers need to know the comparability of the content of the questionnaires used in different countries [1].

Two of the most used scales developed to assess function in patients with lower limb sarcoma are the Toronto Extremity Salvage Score (TESS) and the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society Rating Scale (MSTS rating scale). The TESS is a self-reported evaluation system developed for patients undergoing limb preservation surgery for tumors of the extremities. It has been validated and crossculturally adapted to Brazilian Portuguese [19]. However, the MSTS rating scale is a two-part, six-item questionnaire completed by a clinician. It is based on an analysis of characteristics pertinent to the patient as a whole and of those specific to the affected lower limb. It is widely used in English-speaking countries [11, 12, 20], but its use in other non-English-speaking countries is limited by the lack of translated versions. Moreover, there is a lack of evidence supporting the use of this tool in that it has never been properly validated [22]. Because approximately 180 million people live in Brazil, crosscultural adaptation of the MSTS into Brazilian Portuguese will allow researchers to assess clinical outcomes in this population and compare results with English-speaking populations [23].

It is now widely recognized that instruments intended for use across cultures must not only be translated well linguistically, but also adapted culturally to maintain their content validity across different cultures [3]. Therefore, our purposes with this study were (1) to translate and culturally adapt the MSTS rating scale for functional evaluation in patients with lower extremity bone sarcomas to Brazilian Portuguese; (2) verify if the items from the MSTS are all statistically referring to the same latent factor structure (functional evaluation) as hypothesized in the original version; and (3) test the reliability (4) and validity of the Brazilian MSTS version.

Materials and Methods

Musculoskeletal Tumor Society Rating Scale

The original MSTS rating scale was originally described by Enneking et al. in 1987 and modified in 1993 [8]. It is completed by a clinician and is based on six factors. Three of them are pertinent to patients as a whole such as pain, functional activities, and emotional acceptance and three factors are specific for either the upper limb (positioning of the hand, manual dexterity, and lifting ability) or the lower limb (use of external supports. walking ability, and gait). Each item is rated in a scale of 0 to 5 (0 = bad function and 5 = normal function) with a maximum score of 30. The final score is usually converted to a percentage transforming the results to a range of 0 to 100.

Crosscultural Adaptation

We obtained ethic approval from the hospital ethics committee and translated the English version of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs into Brazilian Portuguese following internationally accepted guidelines described by Beaton et al. [4]. Two bilingual translators (AMB, RMB) whose mother language was Brazilian Portuguese carried out the MSTS rating scale forward translation. One translator was an orthopaedic surgeon and the other one a “naïve” translator who was not aware of the outcome measure. The first translated version was obtained by consensus between the translators. Two bilingual translators, whose mother language was English and who were blinded to the original version of MSTS rating scale, carried out back translation to English (PW, AB). None of the translators were aware or informed about the concepts of the MSTS rating scale. Finally, both of the forward-translated and back-translated versions of MSTS rating scale were submitted to a committee consisting of all individuals involved in the translation process. Both versions were analyzed and compared with the original version and a prefinal version was obtained by mutual consensus. Translation of the MSTS questionnaire was successfully completed without major discrepancies that could not be resolved through consensus. Backward translation resulted in no major semantic or language disagreement.

We presented the preliminary version of the MSTS-Brazilian Portuguese (MSTS-BR) to a group of 10 patients, who met our inclusion criteria, for qualitative evaluation. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were older than 12 years of age, fluent in Portuguese, and underwent limb salvage surgery or amputation for primary sarcoma of the lower limb for at least 6 months before the interview. Subjects were excluded if they were unable to read in Portuguese or had a second orthopaedic condition. Each item was read aloud to the patients and they were asked about their understanding of the meaning of the item. Responses were recorded by the interviewer and were analyzed immediately after each interview. On the basis of this analysis, modifications were made to the questionnaire as necessary, leading to the final version of the Brazilian Portuguese questionnaire, which was subsequently reviewed and approved by the expert committee. No difficulties encountered by the respondents were noted in the pilot study.

Test of Final Version

The final translated version of the MSTS-BR was administered to 67 patients treated for malignant lower extremity bone tumors who were submitted to limb salvage surgery or amputation in a Brazilian sarcoma center (Table 1). The mean age of the sample was 30 years (SD = 13.3) and the mean period from surgery to assessment was 5 years (SD = 4.7; 0.5, 22). Twenty-two patients (33%) were never able to return to work after surgery. They were also evaluated with the Brazilian version of TESS. The patients were evaluated during two sessions comprising three consecutive interviews with MSTS-BR. During the first session, the patients were interviewed twice, once by two different interviewers (AC, RT), to assess interobserver reliability. Test-restest reliability was assessed by repeating the MSTS-BR interview in a second session at least 1 week after the first interview (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics of the participants

| Category | Frequency | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 27 | 40 |

| Male | 40 | 60 | |

| Diagnosis | Osteosarcoma | 41 | 61 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 10 | 15 | |

| Ewing’s sarcoma | 7 | 10 | |

| Others | 9 | 13 | |

| Site | Distal femur | 34 | 51 |

| Proximal femur | 10 | 15 | |

| Proximal tibia | 8 | 12 | |

| Femur (shaft) | 5 | 7 | |

| Foot | 4 | 6 | |

| Others | 6 | 9 | |

| Treatment | Surgery | 17 | 25 |

| Surgery + chemotherapy | 46 | 69 | |

| Surgery + chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 4 | 6 | |

| Reconstruction | Endoprosthesis | 36 | 54 |

| Amputation (any level) | 13 | 20 | |

| Resection without reconstruction | 5 | 7 | |

| Allograft | 3 | 4 | |

| Others | 10 | 15 |

Table 2.

MSTS and TESS mean scores

| Scale | Percent mean score | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Percent floor | Percent ceiling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSTS (n = 67) | 71 | 21.8 | 16.7 | 100 | 0 | 7.4 |

| TESS (n = 67) | 80 | 16.5 | 36.3 | 100 | 0 | 2.9 |

| MSTS–retest (n = 21) | 72 | 23.7 | 20 | 100 | 0 | 9.5 |

| MSTS second examiner (n = 40) | 69 | 23.0 | 16.7 | 100 | 0 | 7.5 |

MSTS = Musculoskeletal Tumor Society; TESS = Toronto Extremity Salvage Score.

Psychometric Analysis

Psychometric properties of the MSTS-BR were evaluated in three steps: (1) latent factor structure: factor analysis that was used to verify the coherence of the six items in the test, assessing if they were all referring to the same concept they are supposed to evaluate (lower limb function). Initially we tested for the feasibility investigating the percentage of missing values [15]. No missing data or outliers were observed in this study.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis [9] was used to determine the number and nature of the latent factors describing the relations between the items of the MSTS-BR. The first step (exploratory factor analysis) was to define the number of latent factors to better explain the relations among the items of the instrument. Criteria adopted to define the appropriate number of factors to retain were analyzed by the scree test, eigenvalues, root mean square SEs, cumulative variance explained by the factor structure, and factor interpretability. These criteria are based on the variance of the items of a test.

The second step was to extract the extent to which the item helps to explain (factor loading) the latent factors. This is performed by the rotation technique, which is used to clarify which variables load into each latent factor, forcing the items to be defined by the simplest factor solution. Rotation was performed through the oblique method that understands that the items in the instrument are correlated. Specifically we applied the rotation method called promax, which extracts the factor loadings considering their independency but also checking for correlation interferences.

Thus, as the third step, the MSTS-BR latent factor structure model was tested (confirmatory factor analysis) through the chi-square test in relation to the null hypothesis model. Through this analysis we were able to obtain the model fit indices indicating the extent to which the MSTS-BR’s factor structure can be trusted. The indicators were root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (values inferior to 0.05 are considered an adequate fit); comparative fit index (values superior to 0.95 are accepted as a good fit); goodness-of-fit index and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (values superior to 0.90 are interpreted as acceptable fit); and Tucker-Lewis Index (acceptable fit with values superior to 0.97) [13].

2) Reliability: to assess if the items in the instrument provide trustworthy values, we investigated the internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and interobserver agreement. Internal consistency of the scale was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the first MSTS-BR interview. Alpha value greater than 0.70 was considered acceptable [5]. Test-retest reliability was examined in a sample of patients with two consecutive interviews with the MSTS-BR in a period of 1 to 12 weeks between them (n = 21 [31.3%]). Interobserver reliability was analyzed after an interview with a second interviewer at the same day of the first interview (n = 40 [59%]). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were used to analyze the reliability of the test-retest and interobserver reliability. ICC values greater than 0.8 are considered good and ICC values greater than 0.9 are considered excellent [7].

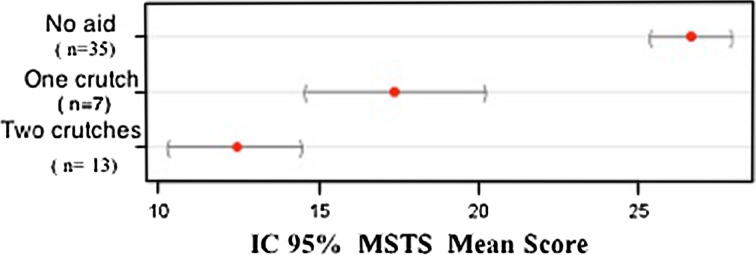

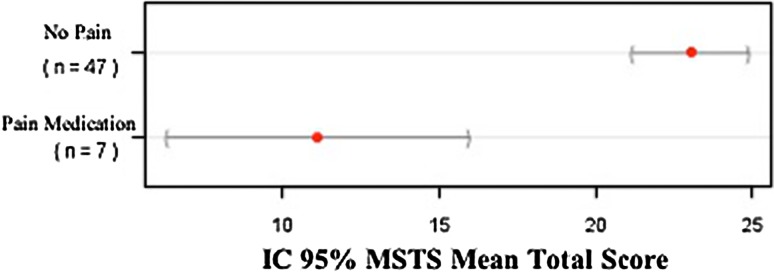

3) Validity: discriminant validity for the MSTS-BR was determined using the known-groups method [10]. This preliminary validity testing focused on discriminating between defined groups where we expected differences in physical function to be present. Based on clinical judgment and the literature, our hypotheses were (1) that participants using continuous pain medication would have lower function scores than patients who did not use pain medication; and (2) participants using a walking aid would have lower functional scores than those who did not use an aid. Thus, we also correlated with the Brazilian version of the TESS to evaluate if the MSTS-BR’s scores would behave in the same direction as the TESS, understanding that they evaluate similar concepts. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was obtained by way of the correlative analysis between MSTS-BR and TESS in Brazilian Portuguese [2].

To test our hypotheses regarding the MSTS score, data were analyzed statistically by analysis of variance at the 5% significance level. Data obtained from the first assessment were used for calculating descriptive statistics. There were no missing data because each questionnaire was assessed for completion right after subjects completed their evaluation. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of SPSS 12.0 for Windows [21], R language software for graphical solutions [18], and Mplus 6.11 [16].

Results

The Brazilian version of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs was translated and found to be easy to use and culturally appropriate. There were no missing data in any of the MSTS-BR scores. Regarding the TESS questionnaire, seven patients (10%) did not answer one or more questions (Table 2).

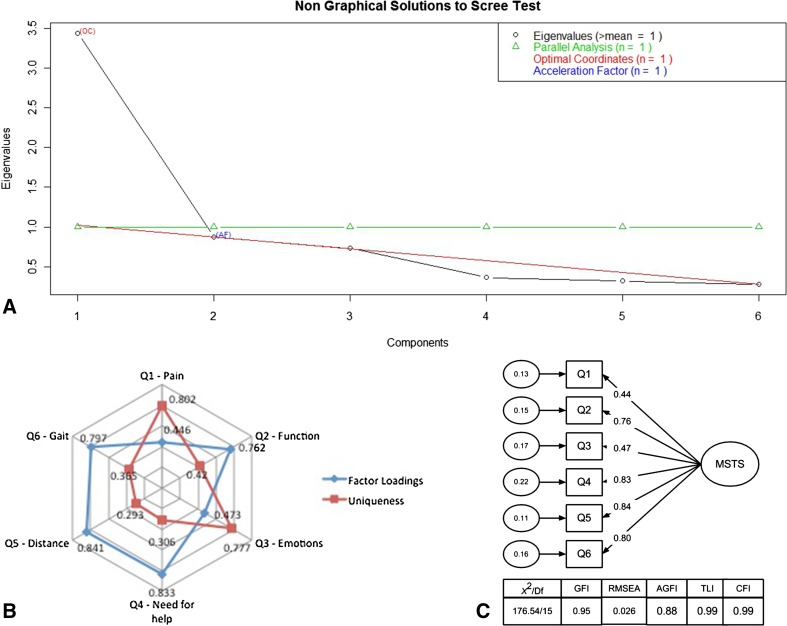

The latent factor structure of the MSTS-BR was proved to be consistent with the original hypothesis of evaluating lower limb function. We observed that the instrument composed by all six items is able to evaluate one latent factor (eg, lower limb function). Scree plot evaluation showed a curve located at the second point, which indicates the possibility of two latent factors; however, there was only one eigenvalue higher than one pointing toward only one factor solution (Fig. 1A). Residuals, factor loadings, and communalities assured the adequacy of the one latent factor model. All items showed factor loadings higher than 0.40 that is the cut of point suggested in the literature. The amount of variance explained by both models was similar (51% and 53%) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1A–C.

The factor structure analysis is shown including (A) Scree plot with eigenvalues of the MSTS’ Brazilian Portuguese version. (B) Factor loadings and uniqueness values for the MSTS’ Brazilian Portuguese version. (C) Confirmatory factor analysis model for MSTS’ Brazilian Portuguese version. df = degrees of freedom; GFI = goodness-of-fit index; AGFI = adjusted goodness-of-fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis fit index; CFI = comparative fit index.

The latent factor structure developed earlier showed good indicators of adequacy indicating that the model was reliable and trustworthy. All fit statistics results showed high model adequacy (being superior to 0.90) and a RMSEA lower than 0.05 (0.027). All the items from the MSTS-BR showed significant paths (arrows in Fig. 1C) toward the latent factor with weights varying from 0.4 to 0.8, indicating that the latent variables (lower limb function) predict adequately the variations in the observed variables (MSTS’ items).

The Brazilian version of the MSTS rating scale was found to be reliable to the lower limb sarcoma sample of patients who speak Brazilian Portuguese. Internal consistency was good for the entire sample with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84. Test-retest reliability was confirmed with an ICC value of 0.92 (n = 21) (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82–0.97) indicating that there was small temporal variance in the subject’s answers. The interobserver reliability was confirmed with an ICC test value of 0.98 (n = 40) (95% CI, 0.95–0.99). There were no significant floor or ceiling effects on scale total scores (Table 2).

The Brazilian version of the MSTS rating scale was found to be valid in a population that speaks Brazilian Portuguese. MSTS scores correlated moderatly and positively with TESS (r = 0.632; 95% CI, 0.462–0.758; p < 0.001) following the theoretical hypothesis. Furthermore, MSTS-BR showed good discriminant validity, proving to be able to discriminate lower limb function among patients with different walking aids patterns (inferior scores to patients with more walking aid need) (Fig. 2) and use of medication (inferior score to patients with use of pain medication) (Fig. 3). These results prove the ability of the MSTS-BR to evaluate the concept (lower limb function) it is supposed to measure.

Fig. 2.

Mean MSTS score with 95% CI by type of walking aid use.

Fig. 3.

Mean MSTS score with 95% CI by use of pain medication.

Discussion

Disability scales have become important and complementary to traditional outcomes measures such as survival or physical assessment in musculoskeletal cancer evaluation. The need for multiple-language versions of existing validated questionnaires plays an important role in standardizing the outcome assessment and increasing the statistical power of clinical studies. The MSTS rating scale was published in 1987 and modified in 1993 and has been universally accepted and used for functional evaluation of patients with sarcomas of the upper and lower limbs. Many researchers have adopted this scale to evaluate functional outcomes in their clinical studies; however, it was never translated to Portuguese and it was unclear if this tool could evaluate health status outcomes and its psychometric properties [14, 24]. In this article we have reported on the translation, psychometric testing, and norming of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs for use among the Portuguese-speaking population of Brazil. Using a universally accepted protocol, translation of the MSTS rating scale into Brazilian Portuguese proved to be relatively straightforward. We examined the MSTS rating scale factor structure and our results support the initial feasibility, reliability, and validity of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs. To the best of our knowledge, the current study is the first to test the factor structure of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs and its reliability properties.

Our study has limitations. One of the major limitations of the present study is the lack of data to evaluate the measures of responsiveness and assess the tool sensitivity to longitudinal change over time. The sample studied is restricted to those with bone sarcomas of the lower limbs, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. We did not study the MSTS rating scale for upper limbs as a result of the smaller number of sarcoma cases in this location and lack of validation of the TESS for upper limbs to Brazilian Portuguese that would require another methodology. Illiterate patients and children younger than 12 years were not evaluated. Future studies using a more heterogeneous group of patients might be needed. Finally, relatively few patients were included in the second interview with the MSTS.

In this study, we presented the crosscultural adaption of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs to Brazilian Portuguese language. The translation and back translation resulted in minimal discrepancies that were resolved by consensus. There were few differences in the cultural adaptation of this instrument, because all activities described by the original questionnaire are similarly present in the Brazilian culture. There were no translation issues and the absence of missing data reflects the good acceptance of the MSTS-BR. This resulted in a translation of the MSTS rating scale that reflected both semantic and conceptual equivalence to the original English version of the questionnaire.

Although the original MSTS rating scale for lower limbs includes three factors relevant to patients as a whole and three factors specific for lower limbs, its factor structure has not been previously tested. In the exploratory factor analysis, we examined three competing models, and the one-factor solution resulted in the best fit model in the exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. The present findings provide strong and consistent evidence that the covariance among the six items of the MSTS rating scale are best explained by a single underlying construct, which was termed lower limb function. To our knowledge, no one has previously investigated the factor structure of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs. However, the present findings need to be replicated in other independent studies.

Scale reliability indices of the MSTS-BR were consistently high and floor and ceiling effects were satisfactory [6]. Our analysis indicates that internal consistency of MSTS-BR was adequate (0.84). This result is similar with that found by Davis et al. [6] (0.91) in a study with 83 patients with lower extremity sarcoma in which the TESS was developed for use in patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Additionally, Lee et al. [14] reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 in a study with 49 patients with musculoskeletal tumors. In summary, the present findings suggest that the MSTS-BR is an internally stable instrument, and these results are consistent with the results of other studies. The original study of Enneking et al. [8] did not evaluate the reliability of the MSTS rating scale for lower limbs. Davis et al. [6] reported that the MSTS rating scale had minimal floor effects (2%) but ceiling effects of 33% and showed good feasibility of this tool, which was completed in 5 minutes. They did not study the test and retest reliability of the MSTS rating scale. Our results were consistent with that seen in the validation study of the TESS.

Discriminant validity of MSTS-BR was made through the known group validation method. The results from the analysis of variance test showed that the MSTS scale distinguished between patients who used pain medication versus patients who did not use pain medication (p < 0.001). It also distinguished among subjects who used two crutches, one crutch, and who do not need walking aids (p < 0.001). Although it is likely that a health status instrument capable of distinguishing between groups at a given point in time will also be responsive to group changes in health over time, this is something that needs to be confirmed by other studies. Another method that we used to establish construct validity of the MSTS-BR was comparing it with the Brazilian version of TESS. The correlation was moderate (r = 0.632) as we expected. This may be seen because the TESS score is focused to evaluate physical disability based on patients’ reports of their function and the MSTS score evaluates physical impairment based on clinical report. This result is similar that found by Davis et al. [6] who compared both scales in patients with soft tissue sarcomas of the thigh and found a mild correlation between them (r = 0.48).

We found our translated, culturally adapted, Brazilian Portuguese version of the MSTS rating system questionnaire for the lower limb to be a culturally appropriate, reliable, and valid instrument for functional assessment of Brazilian patients with bone sarcoma of the lower limbs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Regina Mathias Baptista, Paul Woolcock, and Alexander Bizzocchi for their help in translation; Dr Ricardo Toma and Dr André Ferrari França de Camargo for their help in the interviews; and the team “Research on Research” for their help in preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he, or a member of his immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Orthopaedics and Traumatology Department, University of São Paulo General Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil; and Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA.

References

- 1.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Verrips E. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1055–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander M, Berger W, Buchholz P, Walt J, Burk C, Lee J, Arbuckle R, Abetz L. The reliability, validity, and preliminary responsiveness of the Eye Allergy Patient Impact Questionnaire (EAPIQ) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3:67. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaton D, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Recommendations for the Cross-cultural Adaptation of Health Status Measures. Rosemont, IL, USA: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Institute for Work and Health; 1998.

- 4.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis AM, Wright JG, Williams JI, Bombardier C, Griffin A, Bell RS. Development of a measure of physical function for patients with bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:508–516. doi: 10.1007/BF00540024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson-Sanders B, Trapp RG. Basic and Clinical Biostatistics. Norwalk, CT, USA: Appleton & Lange, Inc; 1994.

- 8.Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;286:241–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:272–299. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of Life: Assessment, Analysis, and Interpretation. New York, NY, USA: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ginsberg JP, Rai SN, Carlson CA, Meadows AT, Hinds PS, Spearing EM, Zhang L, Callaway L, Neel MD, Rao BN, Marchese VG. A comparative analysis of functional outcomes in adolescents and young adults with lower-extremity bone sarcoma. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;49:964–969. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griesser MJ, Gillette B, Crist M, Pan X, Muscarella P, Scharschmidt T, Mayerson J. Internal and external hemipelvectomy or flail hip in patients with sarcomas: quality-of-life and functional outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:24–32. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318232885a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kline P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis. London, UK: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Kim DJ, Oh JH, Han HS, Yoo KH, Kim HS. Validation of a functional evaluation system in patients with musculoskeletal tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;411:217–226. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000069896.31220.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Lu JFR, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 5. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ottaviani G, Robert RS, Huh WW, Jaffe N. Functional, psychosocial and professional outcomes in long-term survivors of lower-extremity osteosarcomas: Amputation Versus Limb Salvage. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:421–436. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saraiva D, de Camargo B, Davis AM. Cultural adaptation, translation and validation of a functional outcome questionnaire (TESS) to Portuguese with application to patients with lower extremity osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:1039–1042. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon MA, Aschliman MA, Thomas N, Mankin HJ. Limb-salvage treatment versus amputation for osteosarcoma of the distal end of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:1331–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SPSS Inc. SPSS Base 12.0 for Windows User’s Guide. Chicago, IL, USA: SPSS Inc; 1999.

- 22.Talbot M, Turcotte RE, Isler M, Normandin D, Iannuzzi D, Downer P. Function and health status in surgically treated bone metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:215–220. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000170721.07088.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor MK, Pietrobon R, Menezes A, Olson SA, Pan D, Bathia N, DeVellis RF, Kume P, Higgins LD. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the short musculoskeletal function assessment questionnaire: the SMFA-BR. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:788–794. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wada T, Kawai A, Ihara K, Sasaki M, Sonoda T, Imaeda T, Yamashita T. Construct validity of the Enneking score for measuring function in patients with malignant or aggressive benign tumours of the upper limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:659–663. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B5.18498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]