Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Leiomyoma of the uterus is the most common type of tumor affecting the female pelvis and arises from uterine smooth muscle. The size of leiomyomas varies from microscopic to giant; giant myomas are exceedingly rare. We report an unusual case of a large, cystic, pedunculated uterine leiomyoma mimicking a primary malignant ovarian tumor on sonography and CT.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

A 58-year-old postmenopausal nulliparous woman presented with a history of lower abdominal pain and distension for a period of approximately 12 months. The patient's personal history revealed difficulty in walking, tiredness and recent weight gain of approximately 25 kg. Sonography and CT examination showed a large mass that filled the abdomen. A preoperative diagnosis of a primary malignant ovarian tumor was made. The patient underwent laparotomy, total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-ooferectomy. The histology revealed a leiomyoma with extensive cystic degeneration.

DISCUSSION

The current established management of uterine fibroids may involve expectant, surgical, or medical management or uterine artery embolization or a combination of these treatments. A surgical approach is preferred for management of giant leiomyomas.

CONCLUSION

Pedunculated leiomyomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a multilocular and predominantly cystic adnexal mass.

Keywords: Uterine leiomyoma, Giant myoma, Cystic degeneration

1. Introduction

Leiomyoma of the uterus is the most common tumor of the female pelvis, which arises from uterine smooth muscle. Such tumors are found in nearly half of women over age 35; the prevalence increases during reproductive age and decreases after menopause.1,2 The size of leiomyomas varies from microscopic to giant. Giant myomas are exceedingly rare.3 However, they can be life threatening if excessive pressure is exerted on the lungs and other contiguous organs. Appropriate surgical management and careful perioperative care are necessary to obtain a good result after removal.4 Here, we present a case of a woman with giant uterine myoma that had undergone cystic degenerative changes, mimicking an ovarian malignancy.

2. Presentation of case

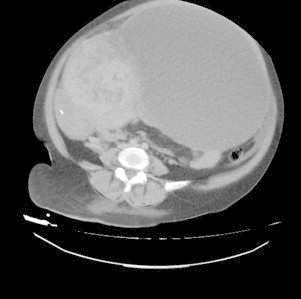

A 58-year-old postmenopausal, nulliparous woman presented with a history of lower abdominal pain and distension for a period of approximately 12 months. The patient's personal history revealed difficulties in walking, tiredness and recent weight gain of approximately 25 kg. Her medical history was normal; she had no history of serious illness or surgical procedures and no family history of malignancies. Her vital signs were all within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed a huge abdominal mass that caused distention. No abdominal tenderness was present. The external genitalia and uterine cervix were normal, but the fornices of the vagina were full on pelvic examination. The uterus did not feel enlarged. It was difficult to specify the origin of the tumor. An abdominal sonogram revealed a large, complex and predominantly cystic mass, approximately 35 cm × 25 cm in size, occupying the whole inferior abdomen. There were multiple fine septations and an irregular solid component in the right posterior corner of the mass, measuring approximately 15 cm × 5 cm. No normal ovaries were detected. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a large semisolid mass that could not be separated from the uterus and an approximately 35 cm × 25 cm cystic mass extending to the spleen adjacent to this mass. There was no regional nodal or distant metastasis.

The results of routine laboratory testing including a complete blood count, serum electrolyte levels, tests of liver and renal function and Pap smear were normal. In the light of the clinical examination and sonographic and CT findings, a primary malignant ovarian tumor was the most likely diagnosis. However, the tumor markers were within normal limits.

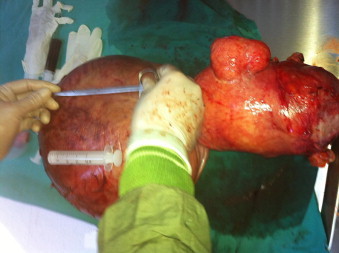

An abdominal midline xiphopubic vertical incision was made. At laparotomy, we found an enlarged, bilobated, complex and predominantly cystic tumor arising from the uterus that filled the entire abdomen and compressed the abdominal organs. The mass was drained of 7 l of old blood. Dense adhesions between the mass and bowel and omentum and spleen were noted. A total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy were performed after dissection of the adhesions. A drain was packed into the pelvis after obtaining hemostasis. The blood loss during surgery has been estimated to be 1 l. Four units of blood were transfused. The drain was removed on the first postoperative day, and the patient was discharged 13 days after the operation in excellent condition.

Gross pathologic examination revealed a smooth, multiloculated cystic mass measuring 33 cm × 20 cm × 18 cm with brownish contents of fluid consistency. The uterus was enlarged to 31 cm × 16 cm × 11 cm. Bilateral ovaries and tubes were normal. Microscopic examination revealed degenerative changes. Areas of cystic degeneration were observed. Histologic signs of malignancy were not found. The final diagnosis was a pedunculated uterine leiomyoma with marked cystic degeneration.

3. Discussion

Uterine fibroid tumors are noncancerous growths in the uterus. Based on their location, leiomyomas are classified as submucosal, intramural or subserozal.5 The latter may be pedunculated and simulates ovarian neoplasms. Large uterine fibroids can cause pain, constipation, increased frequency of micturation and menstrual bleeding. They can also affect reproduction by causing infertility, miscarriage and/or premature labor.1–5

As leiomyomas enlarge, they can outgrow their blood supply, resulting in various types of degeneration, such as hyaline, cystic, myxoid or red degeneration and dystrophic calcification.6 Hyalinization is the most common type of degeneration, occurring in up to 60% of cases. Cystic degeneration, observed in about 4% of leiomyomas, may be considered extreme sequelae of edema.7

Only few cases of giant uterine tumors have been reported in the recent literature. The largest uterine fibroid ever reported weighed 63.3 kg and was removed postmortem in 1888.8 The potential for uterine leiomyomas to grow to an extreme size before causing symptoms is quite remarkable. This is likely due to the relatively large volume of the abdominal cavity, the distensibility of the abdominal wall and the slow growth rate of these tumors.

Typical appearances of leiomyomas are easily recognized on imaging. However, the atypical appearances that follow degenerative changes can cause confusion in diagnosis. Leiomyomas have been misdiagnosed as adenomyosis, hematometra, uterine sarcoma and ovarian masses.

The preferred imaging modality for the initial evaluation is ultrasonography because it is the least invasive and the most cost-effective. The relative echogenicity of leiomyomas depends on the ratio of fibrous tissue to smooth muscle, the extent of degeneration and the presence of dystrophic calcification.9 A CT scan can be useful; however, leiomyomas are indistinguishable from healthy myometrium unless they are calcified or necrotic. MRI can define the anatomy of the uterus and ovaries, but availability and high cost are serious limitations.10

The current established management of uterine fibroids may involve one of the following approaches or a combination thereof: expectant management, surgical management, medical management or uterine artery embolization. The chosen approach should be individualized depending on various factors, including age, type and severity of symptoms, suspicion of malignancy, desire for future fertility and proximity to menopause. A surgical approach is most frequently preferred for management of giant leiomyomas (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Laparotomy material showing giant leiomyoma.

Fig. 2.

Laparotomy material showing giant leiomyoma.

Only the most experienced gynecologic surgeons should attempt such an operation. Even then, intraoperative consultations from gynecologic oncology, general, colorectal, and urology surgeons may be helpful. Intraoperatively, the patient should be positioned to allow adequate ventilation and reduce vena cava compression. The skin incision should allow easy manipulation of the mass and exploration of the upper abdomen. Preoperative mechanical bowel preparation may decrease the risk of bowel injury and aid visualization. Conscientious perioperative management and multidisciplinary patient care are essential to prevent morbidity and mortality (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CT scan of the same patient.

4. Conclusion

Although fibroids typically have a characteristic USG appearance, degenerating fibroids can have variable patterns and pose diagnostic challenges. This case represents an unusual case of a pedunculated leiomyoma masquerading as an adnexal mass. Pedunculated leiomyomas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a multilocular and predominantly cystic adnexal mass.

Conflict of interest

We have no financial or commercial conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and case series and accompanying images.

Author contributions

Cetin Aydin contributed to study design, and Serenat Eris, Yakup Yalcin and Halime Sen Selim contributed to data collection, writing and analysis.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Cetin Aydin, Email: cetinaydin2005@mynet.com.

Serenat Eriş, Email: serenateris@hotmail.com.

Yakup Yalçin, Email: dryakupyalcin@gmail.com.

Halime Şen Selim, Email: dr.halime.sen.selim@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hoffman B. Pelvic mass. In: Schorge J., editor. Williams gynecology. McGraw-Hill Companies; 2008. pp. 197–224. [chapter 9] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courbiere B., Carcopino X. Gynecologie Obstetrique. Vernazobres-Greco; 2006–2007. Fibromes uterins; pp. 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonas H.S., Masterson B. Giant uterine tumors. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;50:2s–4s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inaba F., Maekawa I., Inaba N. Giant myomas of the uterus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;88:325–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novak E.R., Woodruff J.D. Myoma and other benign tumors of uterus. In: Novak E.R., Woodruf J.D., editors. Novak's gynecologic and obstetric pathology. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1979. pp. 260–279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preayson R.A., Hart W.R. Pathologic considerations of uterine smooth muscle tumors. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1995;22:637–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer D.P., Shipilov V. Ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging of uterine fibroids. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1995;22:667–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans A.T., III, Pratt J.H. A giant fibroid uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;54:385–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wladimiroff J. Ultrasound in obstetrics and gynaecology. Elsevier; 2009. Uterine fibroids; pp. 303–306. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casillas J., Joseph R.C., Guerra J.J., Jr. CT appearance of uterine leiomyomas. Radiographics. 1990;10(6):999–1007. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.10.6.2259770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]