Abstract

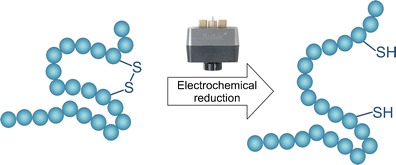

A novel electrochemical (EC) method for fast and efficient reduction of the disulfide bonds in proteins and peptides is presented. The method does not use any chemical agents and is purely instrumental. To demonstrate the performance of the EC reactor cell online with electrospray mass spectrometry, insulin and somatostatin were used as model compounds. Efficient reduction is achieved in continuous infusion mode using an EC reactor cell with a titanium-based working electrode. Under optimized conditions, the presented method shows almost complete reduction of insulin and somatostatin. The method does not require any special sample preparation, and the EC reactor cell makes it suitable for automation. Online EC reduction followed by collision-induced dissociation fragmentation of somatostatin showed more backbone cleavages and improved sequence coverage. By adjusting the settings, the EC reaction efficiency was gradually changed from partial to full disulfide bonds reduction in α-lactalbumin, and the expected shift in charge state distribution has been demonstrated. The reduction can be controlled by adjusting the square-wave pulse, flow rate or mobile phase composition. We have shown the successful use of an EC reactor cell for fast and efficient reduction of disulfide bonds for online mass spectrometry of proteins and peptides. The possibility of online and gradual disulfide bond reduction adds a unique dimension to characterization of disulfide bonds in mid- and top-down proteomics applications.

Figure.

Principle of electrochemical reduction of disulfide bonds in proteins

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00216-013-7374-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Electrochemistry, Mass spectrometry, Disulfide bond reduction, Square-wave pulse, Proteomics

Introduction

Disulfide bonds are some of the most important post-translational modifications of proteins as they stabilize the native conformation of a protein and regulate the protein’s biological function [1]. The determination of the arrangement of the disulfide bonds is crucial for understanding the folding processes of a protein.

Disulfide bond reduction is furthermore a prime requisite for protein identification by mass spectrometry (MS). Any “bottom-up” protocol for identification and sequencing of a protein involves disulfide bond cleavage prior to enzymatic cleavage [2, 3]. In “top-down” approaches, sequence information is obtained from mass spectrometric fragmentation of high-mass multiply charged ions [4]. As proteins with disulfide bonds show resistance to fragmentation, disulfide bond reduction is still necessary for comprehensive sequence analysis by low-energy collision-induced dissociation (CID) [5, 6]. Recently, alternative mass spectrometric-based fragmentation techniques such as electron capture dissociation [7] and electron transfer dissociation [8] have been used to cleave the disulfide bonds and the peptide backbone [8–10]. Furthermore, due to the fact that N-Cα backbone cleavage can be competing with disulfide bond reduction, even for sequencing with the electron capture dissociation and electron transfer dissociation cleavage of disulfide bonds is required [10].

The common approach for disulfide bond cleavage is based on chemical reduction using agents such as dithiothreitol [11] or thiol-free reducing agents as tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) [12] followed by alkylation of free sulfhydryl groups to prevent their spontaneous oxidation and proteolytic digestion (e.g. with trypsin) prior to mass spectrometric analysis [2, 3]. Despite considerable success, this strategy has some limitations. It is usually considered to be time-consuming, and can hardly be adapted for online MS.

In seeking to establish a more advanced method, electrochemistry (EC) has been introduced recently. EC is a purely instrumental approach that can be online hyphenated to MS. EC combined offline and online with mass spectrometry has been successfully used for the investigation of drug metabolism [13], environmental behaviour of xenobiotics [14] but also nucleic acid oxidation [15]. Application of a square wave pulse potential has been described for modulating the electrochemical reaction products [16]. Added value of electrochemistry has also been noticed in protein research [17]. Recently, a paper on the electrochemical oxidation and the oxidative cleavage of tyrosine and tryptophan containing peptides has been published by Roeser et al. [18].

The first report regarding electrochemical reduction of disulfide bonds of proteins was published in 1964 by Cecil et al. [19], and additional reports followed [20, 21]. Disulfide-containing peptides were determined by means of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection (ECD) [22] and by HPLC/ECD and mass spectrometry [23, 24]. Although ECD can detect disulfides at very low levels (e.g. the limit of detection for Vasopressin and Oxytocin was 1 pmol on column [22]), chromatographic fractions had to be collected and sample preparation was required before MS analysis could be conducted [23, 24]. However, the first mass spectrometric analysis of electrochemically cleaved disulfide bonds was accomplished by Girault and co-workers in 2008 [25]. They observed reduction of disulfide bonds during matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) of peptides from targets modified with titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Their method required an addition of glucose, a non-volatile electron donor to the protein before the deposition on the MALDI plate. Chen and co-workers pioneered the use of online EC/MS for reduction of disulfide bonds in peptide and protein. Amalgam [26] and conductive diamond [27–29] was employed as electrode material for disulfide reduction. Mass spectrometric analysis was enabled by desorption electrospray ionization. Although reduction on conductive diamond electrode substantially increased backbone cleavage by different MS fragmentation techniques, the reduction efficiency for proteins was much lower than the reduction by DTT [Fig. S1, see Electronic supplementary material (ESM)] [29]. Our optimized protocol provides not only stable but also very efficient (close to 100 %) reduction of disulfide bonds as well in peptides as in proteins. Furthermore, our method using the electrochemical reactor cell is well suitable for automated online LC/EC/MS or EC/LC/MS applications.

Herein, we present an alternative, electrochemical method for the fast and efficient reduction of disulfide bonds in peptides and proteins. The unique properties of an EC reactor cell with a titanium-based working electrode have been investigated and a special square-wave potential pulse was developed. A complete or near to complete reduction of the disulfide bonds of the tested substances has been demonstrated.

Experimental

Chemicals

Insulin from bovine pancreas, α-lactalbumin from bovine milk and formic acid (99 %) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (The Netherlands). Somatostatin 14 was purchased from Bachem (Switzerland). Acetonitrile (99.9 %) was obtained from Acros organics (Belgium). All these reagents were used as received without further purification. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ.cm) used for all experiments was obtained from a Barnstead Easypure II system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

EC/MS of peptides and proteins

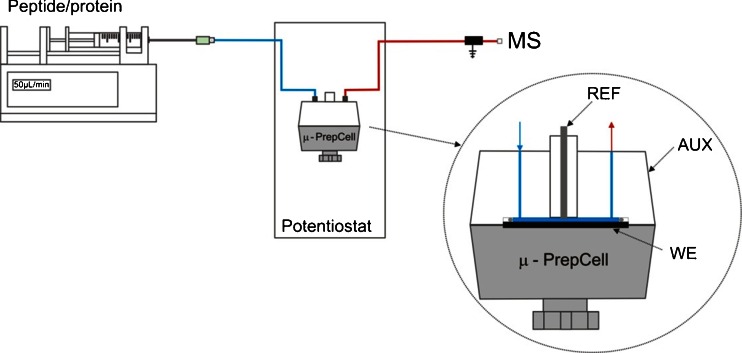

All experiments were performed on a ROXY EC system (Antec, The Netherlands) consisting of a ROXY Potentiostat, equipped with an electrochemical reactor cell (μ-PrepCell, Antec, The Netherlands) and an infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, USA). The Roxy system was online hyphenated to a LTQ-FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). A schematic drawing of the instrumental set-up used is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematics of ROXY EC/MS setup for direct infusion experiments. Shown are: the infusion pump containing the syringe with a protein/peptide sample, the μ-PrepCell placed in the ROXY potentiostat and the grounding union between the EC reactor cell outlet and ESI inlet. The blue line corresponds to 45 cm (0.254 mm id) of PEEK tubing. The red line corresponds to 100 cm (0.127 mm i.d.) of outlet PEEK tubing. In the insert, a more detailed schematic of μ-PrepCell with a working (WE), auxiliary (AUX) and reference (REF) electrode is shown. A blue and red arrow corresponds to the reactor inlet and outlet, respectively. A fluidic path inside the cell is represented as a blue line

Electrochemical disulfide bond reduction was performed in the μ-PrepCell. This thin-layer electrochemical reactor cell consisted of a titanium-based working electrode (WE) specifically optimized for efficient reduction [30], a titanium auxiliary (counter) electrode (AUX) and a Pd/H2 reference electrode (REF). A 150-μm spacer was used to separate the WE and the auxiliary electrode inlet block giving a cell volume of approximately 11 μL. The ROXY EC system was controlled by Dialogue software (Antec, The Netherlands). An electrical grounding union was used to decouple the electrochemical from the ESI high voltage. The connections were made of PEEK tubing (127 μm i.d.). Details of the square-wave pulses used to accomplish disulfide reduction are shown in Fig. 2. Aqueous solutions of 0.9–5-μmol/L solutions of the insulin (900 nmol/L), somatostatin (3 μmol/L) and α-lactalbumin (5 μmol/L) containing 1 % formic acid and 10–50 % ACN were used for EC/MS experiments. Sample solutions were delivered to the electrochemical cell by the integrated infusion pump. The flow rate was set to 50 μL/min. For tuning the reduction efficiency flow rates up to 200 μl/min were applied. The electrochemical cell was thermostated to 35 °C.

Fig. 2.

A schematic representation of the square-wave pulse. Under optimized conditions, the potentials were −1.5 V (E1) and +1.0 V (E2) and time intervals were 1,990 ms (t1) and 1,010 ms (t2), unless specified otherwise

Mass spectrometric experiments were performed on an LTQ-FT mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). ESI-MS was performed in positive ion mode. For each peptide/protein, optimization of mass spectrometric conditions was accomplished by infusion of the native form. The spray voltage ranged between 3.2 and 3.6 kV. The sheath gas was set to 15–20 arbitrary units (AU), and the auxiliary gas was set 0–5 AU. Tube lens voltages of 90–200 V were used. The transfer capillary temperature was set to 275 °C. MS spectra were recorded from 100 to 2,000 m/z with the FT analyzer at a resolution of 100,000. For selected optimization experiments only LTQ analyzer was used to register MS spectra. MS/MS spectra were generated by CID in the ion trap. Normalized collision energies of 15–35 % were used to initiate fragmentation. MS/MS spectra were acquired with the LTQ analyzer. Accumulation times varied from 100 ms for the LTQ to 500 ms for FT. Mass spectra were recorded with Xcalibur software (version 2.0.7, Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA).

Results

EC/MS of insulin

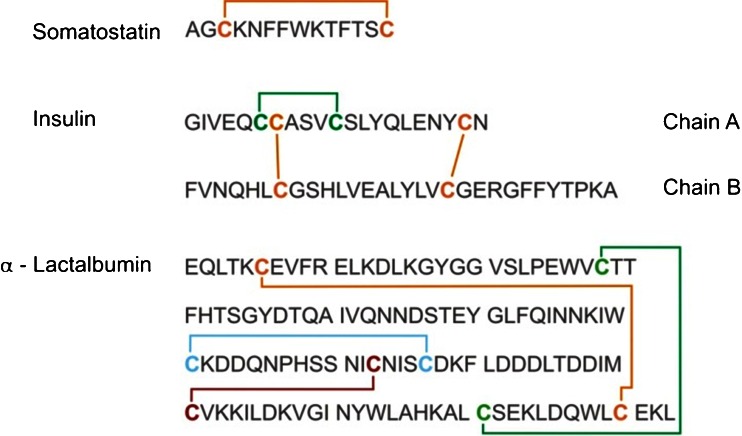

Insulin consists of 51 amino acids forming two chains, A and B, and contains 3 disulfide bonds. Two inter-chain disulfide bonds connect chain A and B and one intra-chain disulfide bond is located on chain A (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Sequence of somatostatin, bovine insulin and α-lactalbumin. Positions of disulfide bonds are indicated

Disulfide bond reduction cleaves the molecule. Thus, chain A and B are unequivocally distinguishable from the native form by MS. Accordingly, insulin is ideally suited as model compound to characterize the efficiency of electrochemical disulfide bond reduction. The reduction efficiency can be easily established by measuring the percent disappearance of the substrate and appearance of product. For further optimization experiments, appearance of chain B was chosen as an insulin reduction marker.

Efficiency was calculated as ratio between signal abundance of insulin with no potential applied (CellOFF, no reduction) and with a square-wave pulse applied (CellON, reduction) according the following equation: 100 % × (CellOFF − CellON)/CellOFF. Where CellOFF and CellON correspond to the abundance of the average mass spectra from the plateau region measured in the narrow selected ion monitoring mode (mass range of 1,140–1,170). The +5-fold protonated ion of intact insulin observed at m/z 1,147 was chosen to calculate the efficiency.

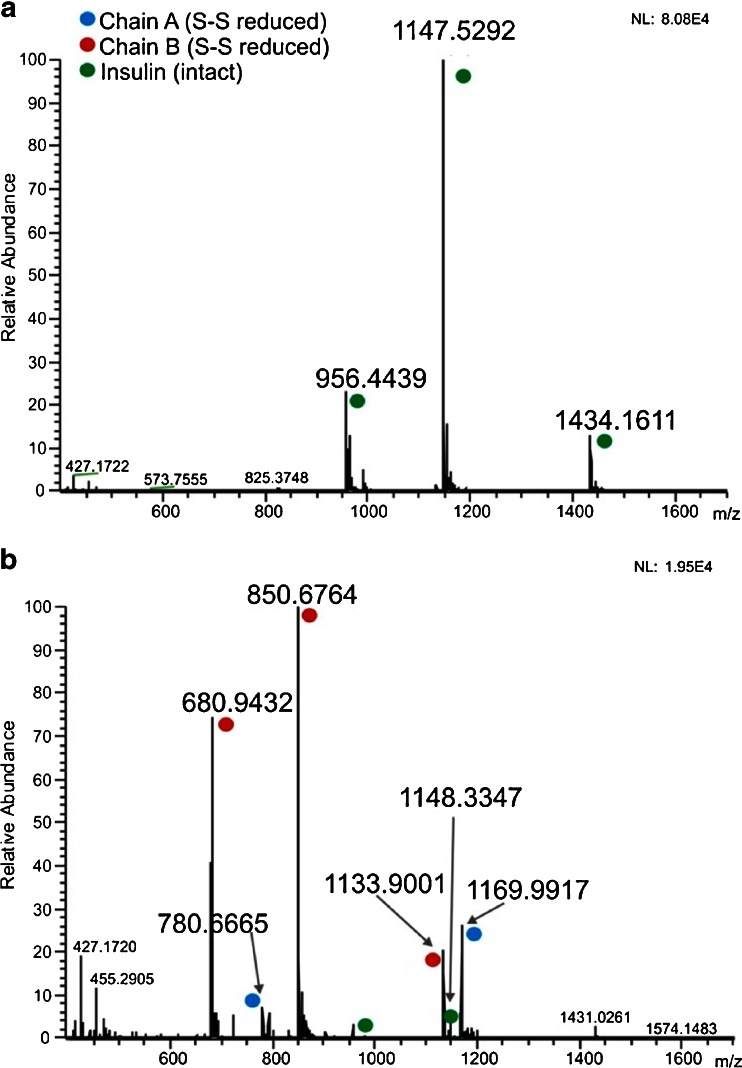

The mass spectrum of the native form of insulin is shown in Fig. 4a. [M+4H]4+, [M+5H]5+, [M+6H]6+ ions were observed. The mass spectrum obtained after online electrochemical reduction is depicted in Fig. 4b. As expected, electrochemical disulfide bond reduction gave rise to cleavage of insulin. Nevertheless, mainly ions corresponding to chain B were detected as [M+3H]3+, [M+4H]4+, [M+5H]5+ (Fig. 4b). Chain A contains multiple acidic residues (glutamic acid at position 4 and 17) and is therefore difficult to detect in positive ion mode [31]. However, two low abundant peaks at m/z 1,169 and 780 were observed in the mass spectrum and are in agreement with theoretical masses of reduced [M+2H]2+ and [M+3H]3+ ions of chain A (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the isotopic pattern for the [M+3H]3+ ion shows that the intra-chain disulfide bond is near 100 % reduced, and only low abundant ions of the species with the intra-bond present are observed (Fig. S2, ESM). Based on the reduction of the abundances of insulin ions, a reduction efficiency of >98 % was determined.

Fig. 4.

Mass spectra of 0.9 μmol/L insulin in 1 % formic acid and 10 % ACN with EC reactor cell OFF (a) and ON using a Ti-based working electrode (b). For pulse settings see Fig. 2

For efficient disulfide bond reduction proper selection of experimental conditions is essential. During method development, the electrode material, the square wave potential settings, the solution composition and the flow rate were identified as parameters influencing the reduction efficiency observed for insulin.

A Ti-based electrode in combination with square-wave pulses was found to provide constantly high reduction efficiency. Mechanistic details of electron transfer reactions (redox reactions) at oxide-covered metal electrodes are well understood [32, 33]. Generally, metal electrodes need a distinct thin layer of metal oxide to catalyze the redox reaction; however, increasing thickness of the oxide layer may have a negative effect on the electron transfer rate [34]. To avoid electrode fouling, a square-wave pulse with an alternating positive and negative potential was developed (Fig. 2). During the oxidative potential, a metal oxide layer is formed on the WE, which is subsequently removed during the reductive potential of the square wave. As a result, the oxide layer does not accumulate and the surface of the working electrode remains active.

The importance of alternating the polarity of the potential is illustrated by changing the positive potential of E2 to a negative potential, which resulted in a significantly lower reduction yield as shown in Fig. S3 (ESM). Subsequently, at constant E2 of 1 V the E1 potential values between −0.5 V and −3 V were tested showing different reduction efficiency. Figure S4 (ESM) shows comparison between E1 = −0.7 V and E1 = −1.5 V. A more negative E1 potential results in more efficient reduction.

Also the duration, t1 and t2 of the potential steps can be used to achieve partial or full disulfide reduction. Typically, E1 was applied for 2,000 ms and E2 for 1,000 ms, and conversion of intact insulin was approximately 98 % (Fig. 4a, b). Shortening t1 and t2 to 200 ms and 100 ms, respectively, resulted in lower conversion of insulin of about 50 % (data not shown here). With this example, we demonstrate a convenient way to modulate the reduction efficiency by tuning the square-wave pulse parameters E1, E2 and the time intervals. This is particularly useful for assignment of disulfide bonds in proteins, when controlled partial reduction is desired, rather than 100 % reduction.

Electrochemical reduction was found to work well in aqueous solutions containing formic acid and acetonitrile as modifiers. These compounds are commonly used mobile phase additives in LC/MS of proteins and peptides. In comparison to standard LC/MS conditions, however, 0.5–1 % formic acid should be added to the sample solution to ensure efficient reduction. Formic acid is used as supporting electrolyte and can enhance the electron exchange. It can be considered as an electron donor and used as reducing agent [35]. With respect to the acetonitrile content, the reduction efficiency was only slightly decreased (to 87 % based on the decrease in abundance of the +5-fold protonated intact insulin ion) by increasing the concentration of acetonitrile to 50 % comparing to the typically used 10 % acetonitrile solution.

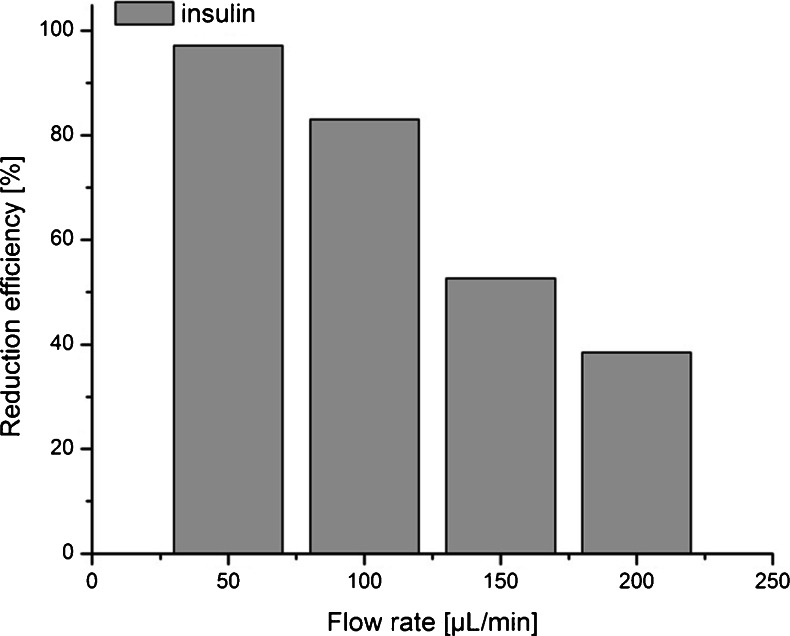

The impact of the flow rate on performance is shown in Fig. 5 (for more information see also Fig. S5 in ESM). At 50 μl/min, almost complete reduction of insulin was achieved. By increasing the flow rate, a decrease of insulin cleavage was observed. This observation clearly suggests that the flow rate can be used to control the reduction efficiency. Thus, by proper setting of the flow rate it should become possible to switch between complete and partial disulfide bond reduction. Partial reduction could be of particular importance to localize disulfide bonds and to study the impact of individual disulfide bonds on peptide and protein structures (see below).

Fig. 5.

Reduction efficiency of insulin as a function of flow rate

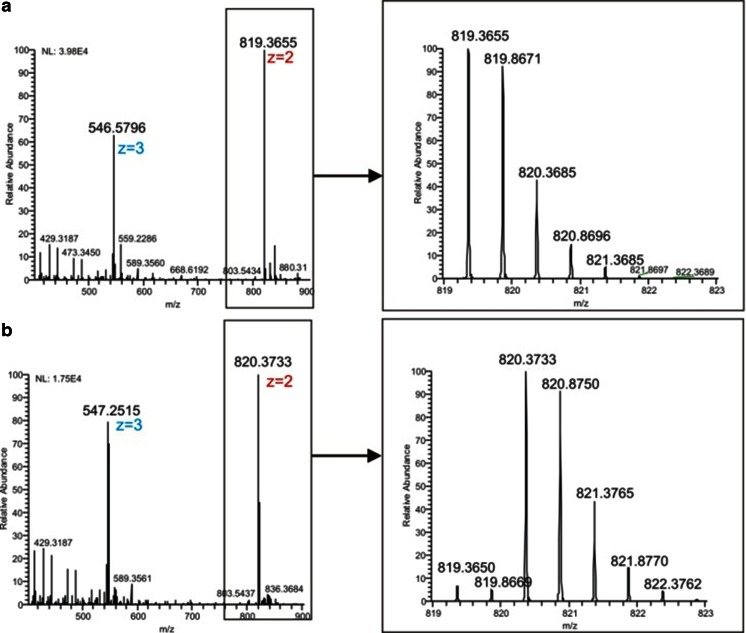

EC/MS of somatostatin

Somatostatin was selected as target to demonstrate the usefulness of EC/MS for studying peptides containing an internal disulfide bond (Fig. 3). Somatostatin (also called somatropin) is a peptide hormone. There are two active forms; the peptide containing 14 amino acids and an internal disulfide bridge was used for this study. The mass spectrum of the native form of somatostatin is shown in Fig. 6. The monoisotopic peak of the [M+2H]2+ ion was detected at 819.3655 m/z. After electrochemical reduction, the m/z values were shifted to 820.3733 indicating the cleavage of the disulfide bond (Fig. 6). Based on the reduction of the intensity of 819.3655 m/z, a reduction efficiency of >90 % was determined.

Fig. 6.

Mass spectra of 3 μmol/L somatostatin in 1 % formic acid and 10 % ACN with reactor cell OFF (a) and ON (b) and a close up of the isotopic distribution of the [M+2H]2+ ions. Pulse settings are the same as in Fig. 2

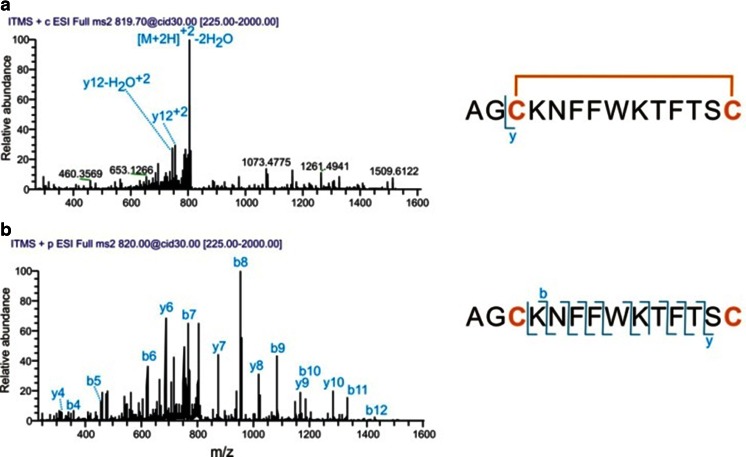

Disulfide bond cleavage can be of particular importance for obtaining high sequence coverage in MS/MS experiments. This is demonstrated by CID of the native and the reduced forms of somatostatin (Fig. 7). In the CID spectrum of the native somatostatin, only one abundant fragment ion was detected. This ion was identified as the y12-ion produced by cleavage of the first two amino acids (outside the loop formed by the disulfide linkage). After electrochemical reduction of the peptide, almost full series of y- and b-type ions were detected which enabled unequivocal peptide identification via de novo sequencing and library search.

Fig. 7.

CID fragmentation of 3 μmol/L somatostatin in 1 % formic acid and 10 % ACN with the EC reactor cell OFF (a) and ON (b). The sequence of somatostatin with indicated backbone cleavages is shown. Pulse settings are the same as in Fig. 2. Mass spectra were recorded with a LTQ analyzer

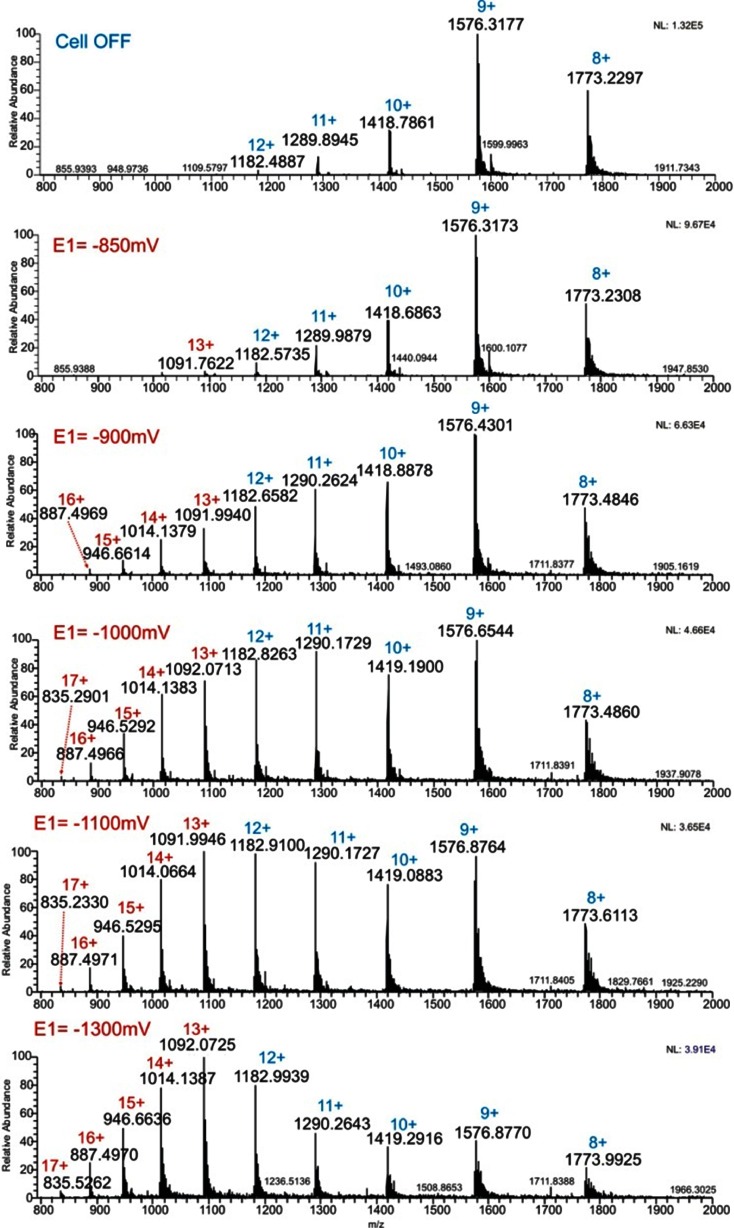

EC/MS of α-lactalbumin

α-Lactalbumin was chosen to demonstrate the usefulness of EC/MS for studying proteins containing multiple internal disulfide bonds. α-Lactalbumin contains 123 amino acids. The globular structure of α-lactalbumin is stabilized by four disulfide bonds: Cys6-Cys120, Cys28-Cys111, Cys61-Cys77 and Cys73-Cys91 (Fig. 3). The mass spectrum of the native protein is shown in Fig. 8. The charge states observed ranged from +8 to +12; the most abundant ion was the nine times positively charged ion. The electrochemical reduction caused a shift of the charge state distribution to more highly charged ions (Fig. 8). In the fully reduced form, the [M+13H]13+ ion showed the highest signal abundance. Obviously, reduction of disulfide bonds facilitated unfolding of the protein, which enabled accumulation of a larger number of charges on the surface of the protein. This phenomenon has also been described in literature [36, 37] and was confirmed by Zhang et al. [28] recently. Furthermore, the reducing potential was used as a means to control the extent of disulfide bond cleavage. More negative potentials gave rise to an increased shift of the charge state distribution indicating increased disulfide bond cleavage and unfolding of the protein. This partial opening might find immediate application in top-down proteomics for the location of disulfide bonds as well as to study their individual accessibility. Figure 9 shows a close up of the [M+9H]9+ ion of α-lactalbumin measured with the EC reactor cell off (no reduction) and on with two different E1 potentials of −1,000 and −1,300 mV. The overlapping isotopic patterns correspond to different reduction states of the protein including also α-lactalbumin with all bonds reduced.

Fig. 8.

Mass spectra of 5 μmol/L α-lactalbumin in 1 % formic acid and 50 % acetonitrile with the EC reactor cell OFF (top) and ON with different E1 potentials as noted in the figure. The E2 potential was 1,000 mV, t1 and t2 was set to 1,990 and 1,010 ms, respectively (for pulse settings see also Fig. 2). The charge state corresponding to the native protein (with the reactor OFF) is labeled in blue. The multiply charged ions appearing as a result of the electrochemical reaction have the charge state indicated in red

Fig. 9.

Zoom of the overlapping isotopic pattern of the +9 ion of α-lactalbumin measured with the EC reactor cell turned OFF (top), and ON at E1 = −1,000 mV and E1 = −1,300 mV. E2 was 1,000 mV in both cases. See also Fig. 2 for pulse settings. The protein was dissolved in 1 % formic acid and 50 % acetonitrile. The bottom panel shows the isotope simulation for α-lactalbumin with all four bonds reduced. Simulation was done using Xcalibur software. The highest peak in each spectrum is labeled in bold

Conclusions

We have shown the successful use of EC reactor cell with a titanium-based working electrode for reduction of disulfide bonds in proteins and peptides. The method is fast, efficient and robust. Due to use of volatile solvent additives (i.e. formic acid and acetonitrile), the electrochemical reduction can be hyphenated online to MS. Furthermore, the reduction efficiency is controllable by tailoring experimental conditions, such as the flow rate and the square wave pulse settings. This enables to easily switch between complete and partial reduction. Complete reduction was found to be beneficial to increase the sequence coverage in CID. Partial reduction might enable the location of disulfide bonds within proteins and peptides as well as studies on their accessibility.

The electrochemical reduction shows great potential in proteomics applications particularly for the assignment of disulfide bonds in proteins and the cleavage of TCEP-resistant disulfide bonds is important for hydrogen–deuterium (H–D) exchange.

To obtain detailed information on the assignment of disulfide bonds in a protein, a 100 % reduction of all bonds is not always desirable. The use of a chemical reductant leads usually to 100 % reduction, and the information about the assignment of disulfide bonds is lost. The electrochemical reduction can be a very good alternative for disulfide bond assignment in proteins. Simply by turning on the EC reactor cell and changing the settings, partial to full reduction can be achieved. The reduction rate can be controlled in several ways, e.g. by adjusting the square-wave pulse, flow rate, temperature, mobile phase or cell volume (spacer) giving new opportunities for disulfide bonds assignment studies. Recently, Zheng et al. reported selective disulfide bond reduction at different potentials using an online EC reactor cell, a conductive diamond working electrode and a pepsin column for digestion [29].

Disulfide bond reduction using an EC reactor cell is of particular interest for H–D exchange experiments. H–D exchange is used to analyse the tertiary structure of proteins, by exposing them in their natural folded state to deuterons. Regions of a protein that are easily accessible by the solvent will exchange rapidly, folded regions hardly exchange. For reliable results the back-exchange must be minimized (quenched), and after disulfide bond reduction and protein proteolysis the peptide fragments must be analysed as quickly as possible [38]. Traditionally the disulfide bond reduction is performed under quench conditions (pH 2.5 and 0 °C) using a chemical reductant such as TCEP. However, under these conditions TCEP has limited efficiency [39]. The electrochemical reduction using an EC reactor cell is efficient under quench conditions, and furthermore, the residence time in the EC reactor cell to obtain full reduction is only 10–15 s. The application of EC reduction for H–D exchange in proteins was recently presented by Mysling and co-workers during ASMS 2013 conference in the oral presentation entitled “Electrochemical reduction of disulfide bonds for use in protein hydrogen/deuterium exchange monitored by mass spectrometry”. Future investigations will be focused on LC/EC/MS method for electrochemical reduction of proteins and peptides including reduction of disulfide bonds in the high molecular weight proteins as antibodies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 990 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the division of Analytical BioSciences (Leiden University, The Netherlands) for access to their MS facility and to thank Prof. Dr. Herbert Oberacher (Institute of Legal Medicine, Innsbruck Medical University, Austria) for his valuable discussions during the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Hogg PJ. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:210–214. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aebersold R, Mann M. Nature. 2003;422:198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domon B, Aebersold R. Science. 2006;312:212–217. doi: 10.1126/science.1124619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armirotti A, Damonte G. Proteomics. 2010;10:3566–3576. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mormann M, Ebne J, Schwöppe C, Mesters RM, Berdel WE, Peter-Katalinić J, Pohlentz G. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;392:831–838. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorman J, Wallis TP, Pitt JJ. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2002;21:183–216. doi: 10.1002/mas.10025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zubarev RA, Kelleher NL, McLafferty FW. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;13:3265–3266. doi: 10.1021/ja973478k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Syka JEP, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9528–9533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zubarev RA, Kruger NA, Fridriksson EK, Lewis MA, Horn DM, Carpenter BK, McLafferty FW. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2857–2862. doi: 10.1021/ja981948k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole SR, Ma X, Zhang X, Xia Y. J Am Soc Mass Spectr. 2012;23:310–320. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zahler WL, Cleland WW. Biochemistry. 1964;3:480–482. doi: 10.1021/bi00892a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Getz EB, Xiao M, Chakrabarty T, Cooke R, Selvin PR. Anal Biochem. 1999;273:73–80. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jahn S, Karst U. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1259:16–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2012.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Hofmann D, Klumpp E, Xiang X, Chen Y, Stephan Küppers S. Chemosphere. 2012;89:1376–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.05.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erb R, Plattner S, Pitterl F, Brouwer HJ, Oberacher H. Electrophoresis. 2012;33:614–621. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nouri-Nigjeh E, Permentier HP, Bischoff R, Bruins AP. Anal Chem. 2011;83:5519–5525. doi: 10.1021/ac200897p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Permentier HP, Bruins AP, Bischoff R. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2008;8:46–56. doi: 10.2174/138955708783331586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roeser J, Alting NFA, Permentier HP, Bruins AP, Bischoff R. Anal Chem. 2013;85:6626–6632. doi: 10.1021/ac303795c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cecil R, Weitzman PDJ. Biochem J. 1964;93:1–11. doi: 10.1042/bj0930001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Honeychurch MJ. Bioelectroch Bioener. 1997;44:13–21. doi: 10.1016/S0302-4598(97)00062-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuznetsov BA, Shumakovich GP, Mestechkina NM. J Electroanal Chem. 1988;248:387–398. doi: 10.1016/0022-0728(88)85099-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garvie CT, Straub KM, Lynn RK. J Chromatogr. 1987;413:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(87)80212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Y, Andrews PC, Smith DL. J Protein Chem. 1990;9:151–157. doi: 10.1007/BF01025306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Y, Smith DL, Shoupt RE. Anal Biochem. 1991;197:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90357-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiao L, Bi H, Busnel J-M, Liuand B, Girault HH. Chem Commun. 2008;47:6357–6359. doi: 10.1039/b813283f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Dewald HD, Chen H. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1293–1304. doi: 10.1021/pr101053q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu M, Wolff C, Cui W, Chen H. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;403:345–355. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5665-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Cui W, Zhang H, Dewald HD, Chen H. Anal Chem. 2012;84:3838–3842. doi: 10.1021/ac300106y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Q, Zhang H, Chen H. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraj AU, Brouwer HJ, Chervet JP (2012) US13/608907

- 31.Loo JA, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Light KJ, Edmonds CG, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 1992;64:81–88. doi: 10.1021/ac00025a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyons MEG, Brandon MP. J Electroanal Chem. 2010;641:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2009.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stitz A, Buchberger W. Electroanal. 1994;6:251–258. doi: 10.1002/elan.1140060312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boukhalfa S, Evanoff K, Yushin G. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5:6872–6879. doi: 10.1039/c2ee21110f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garron A, Epron F. Water Res. 2005;39:3073–3308. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loo JA, Edmonds CG, Udseth HR, Smith RD. Anal Chem. 1990;62:693–698. doi: 10.1021/ac00206a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Katta V, Brian T, Chait BT. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:8534–8535. doi: 10.1021/ja00022a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wales TE, Engen JR. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2006;25:158–170. doi: 10.1002/mas.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cline DJ, Thorpe C. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15195–15203. doi: 10.1021/bi048329a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 990 kb)