Abstract

Theory suggests temperamental reactivity [negative affectivity (NA)] and regulation [effortful control (EC)] predict variation in the development of emotion regulation (ER). However, few studies report such relations, particularly studies utilizing observational measures of children’s ER behaviors in longitudinal designs. Using multilevel modeling, the present study tested whether (1) between-person differences in mean levels of mother-reported child NA and EC (aggregated across age) and (2) within-person changes in NA and EC from the ages of 18 to 42 months predicted subsequent improvements in laboratory-based observations of children’s anger regulation from the ages of 24 to 48 months. As expected, mean level of EC (aggregated across age) predicted longer latency to anger; however, no other temperament variables predicted anger expression. Mean level of EC also predicted the latency to a child’s use of one regulatory strategy, distraction. Finally, decreases in NA were associated with age-related changes in how long children used distractions and how quickly they bid calmly to their mother. Implications for relations between temperament and anger regulation are discussed in terms of both conceptual and methodological issues.

Keywords: emotion regulation, temperament, longitudinal studies, preschool

Introduction

Emotion regulation (ER), the ability to modulate emotion in order to accomplish goals, is associated with many childhood outcomes, including social competence, school readiness, and psychiatric problems (Eisenberg, Spinrad, & Eggum, 2010). Given its implications for children’s development, it is necessary to understand the sources of individual differences in ER. Temperament models focus on individual differences in emotionality (Goldsmith et al., 1987), and child temperament is widely regarded as a major influence on the development of ER (Calkins, 1994). Studies relating child temperament and ER usually assess temperament at one time point, typically in infancy, and rely on maternal report of both temperament and ER, which may inflate relations (Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1993). There are only a few longitudinal studies suggesting that early temperament influences the development of ER, and these generally cover a brief time span in infancy. To better understand how temperament contributes to notable age-related advances in ER (Kopp, 1989), studies should focus on longer time frames during developmentally important periods using parent-report and observational methods. The present study investigated prospective relations during the period when self-regulation of emotion emerges, with the aim of assessing the degree to which prior child temperament predicts subsequent ER. Specifically, we examined age-related changes in mother-reported child temperament six months prior to laboratory-based observations of child ER behaviors.

Negative Affectivity, Effortful Control, and ER

Child temperament has been largely conceptualized as having two dimensions that relate to ER: (1) reactivity or negative affectivity (NA), defined as the frequency and intensity of reactions to changes in the environment, and (2) regulation or effortful control (EC), defined as deliberate efforts to modulate attention, emotion, and behavior (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). EC involves the ability to inhibit a prepotent response in favor of a subdominant response and, with regard to ER, the ability to modulate reactivity or NA (Rothbart & Sheese, 2007).

Furthermore, this model regards temperament as a developmental construct with NA declining over early childhood as EC increases (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). EC begins to develop in the third year, in part, due to the maturing executive attention system (Posner & Rothbart, 2000; Rueda, Posner, & Rothbart, 2004). This postulate is supported by longitudinal evidence that EC becomes relatively stable around 22–30 months (e.g., Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000) and by experimental evidence that children cannot correctly complete spatial attention tasks requiring executive attention until after the age of 30 months (Gerardi-Caulton, 2000). Notably, advances in ER coincide with the developmental timing of EC. Although infants engage in rudimentary ER behaviors, which are regarded as a form of reactive control (Eisenberg & Sheffield-Morris, 2003; Graziano, Calkins, & Keane, 2011), children can initiate deliberate regulatory strategies that help them forestall and modulate emotional reactions by 36 months (Cole et al., 2011; Supplee, Skuban, Trentacosta, Shaw, & Stoltz, 2011). Thus, assessment of temperament before and after the age of three years should reveal whether age-related changes in temperamental reactivity and regulation are associated with improving ER.

Children with high levels of NA are thought to have difficulty with ER because the intensity and frequency of their reactions tax both their regulatory resources and ability to learn from environmental input (e.g., adult instruction) more difficult (Calkins, 1994). In contrast, aspects of EC (attention shifting/focusing and inhibitory control) should support ER (Rothbart & Sheese, 2007). For example, young children become angry when their goals are blocked, such as having to wait for something they want. EC should help a child deliberately redirect attention away from a desired, but prohibited, goal or bid calmly for support about the challenge of waiting (Posner & Rothbart, 2000). That is, instead of angrily demanding a desired toy (‘Mine!’), EC should aid a child’s ability to deliberately distract from the desired object and to another activity or delay anger while talking about waiting (‘I can have it when you are done, right?’).

Relations between NA and ER

Observational studies using laboratory tasks that block goals in order to elicit child anger find that parent-reported NA is associated with the frequency, duration, and intensity of anger expressions (e.g., Calkins & Johnson, 1998; Rothbart, Ziaie, & O’Boyle, 1992) and inversely with the frequency and duration of distraction (e.g., Buss & Goldsmith, 1998; Calkins, Dedmon, Gill, Lomax, & Johnson, 2002; Rothbart et al., 1992). Longitudinal studies find that higher NA at the age of 5 months predicted fewer regulatory behaviors by 10 months (Braungart-Reiker & Stifter, 1996), and higher levels of infant NA predicted decreased attentional control at 30 months (Gaertner, Spinrad, & Eisenberg, 2008).

Relations between EC and ER

Higher levels of parent-reported EC are associated with fewer anger expressions in a laboratory task at the age of 22 months (Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2000) and in preschool classroom observations (Hanish et al., 2004). Similarly, among infants and toddlers, higher EC is associated with the frequency and duration of regulatory behaviors like distraction (Calkins & Dedmon, 2000; Rothbart et al., 1992). However, studies targeting child ER behaviors typically focus on infancy and do not address whether changes in temperamental NA and EC after infancy are associated with children’s self-regulation of anger.

Relations among NA, EC, and ER

The prevailing view is that NA and EC interact to influence the development of ER in two ways (Rothbart & Bates, 2006): (1) higher levels of NA interfere with the development of EC and, consequently, ER and (2) higher levels of EC buffer the detrimental influence of NA by allowing reactive children to regulate strong emotions. Few studies have addressed the interaction of NA and EC in early childhood. Increases in NA during infancy predicted lower levels of EC in the toddler and preschool years (Hill-Soderlund & Braungart-Rieker, 2008). EC also moderated associations between higher NA and mother-reported social problems (Belsky, Friedman, & Hsieh, 2001). However, studies that tested whether EC moderated the association between NA and observed regulatory behaviors, or child behavior problems associated with poor ER, failed to find the effect (Belsky et al., 2001; Eisenberg et al., 2010; Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005). The present study therefore includes an examination of how interactions between NA and EC relate to age-related changes in anger regulation.

In sum, EC and NA should influence developmental changes in ER during early childhood. However, there is a dearth of evidence to demonstrate whether and how these temperamental dimensions relate to the normative decline in anger reactivity between toddler and preschool ages and the emergence of self-initiated, deliberate ER strategies like attention redirection (e.g., distraction) and calm bids for support.

Measurement Issues

Although temperamental EC and ER are closely related, ER behaviors are thought to emerge through interactions among maturational processes, socialization, and temperament (e.g., Fox & Calkins, 2003). It is also known that emotional reactivity is not readily distinguished from ER (Campos, Frankel, & Camras, 2004; Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004), which is also due in part to measurement issues. If both constructs are measured by parent report, there is the risk of conflated relations. Concerns about shared method variance can be addressed by using observational measures of temperament or ER. However, because there is some overlap in tasks used to observe temperamental characteristics and ER behaviors, researchers should be careful to not include observation measures from the same task when purportedly assessing different constructs. This is particularly important in studies of ER and temperament because tasks from a standard assessment battery of temperament are often used to assess ER behaviors (LabTAB; Goldsmith & Reilly, 1993).

As such, in order to minimize shared method variance, the present study uses different measurement approaches for assessing child temperament and ER. Most studies use parent report of child temperament for which judgments are based on knowledge of the child over time and different situations. To study the effects of changes in temperament on subsequent changes in ER, we assessed mother-reported temperament at three time points and observed child ER at three different time points. Moreover, this approach enables the examination of prospective relations between child temperament and anger regulation.

Expressive behavior conveys the valence of emotional reactions; temporal characteristics of these expressions are thought to index regulatory influences on emotion (Davidson, 1998; Thompson, 1990; Thompson, 1994). The present study assessed the intensive and temporal (i.e., latency and duration) characteristics of children’s anger and two regulatory strategies (distraction and calm bids to mother) during a task that is designed to elicit anger by requiring a child to wait for a desirable gift. If temperament contributes to individual differences in ER, then NA and EC should influence the intensive and temporal (i.e., latency and duration of expression) characteristics of child anger expression and regulatory behaviors.

The Present Study

In sum, the present study examined whether age-related changes in NA and EC, assessed at child age 18, 30, and 42 months, predicted age-related changes in child ER behaviors at the age of 24, 36, and 48 months. We hypothesized that higher levels of mother-reported EC and lower levels of NA, aggregated across three ages, would predict age-related improvements in anger regulation, as evidenced by (1) longer onset, or latency, to anger expression and less intense, shorter expressions and (2) quicker onset, or shorter latency, to and longer engagement, or duration, in two regulatory behaviors: distraction and calm bids. Moreover, because temperament is thought to develop in early childhood, we hypothesized that within-person increases in child EC and decreases in NA (changes relative to a child’s initial level at the age of 18 months) would more strongly predict improvements in child anger regulation than age-aggregated measures describing mean temperament levels. Finally, we hypothesized that the interaction of NA and EC would predict changes in ER, such that children with higher levels of NA would have better anger regulation if they also had higher EC.

Method

Participants

A multistage recruiting strategy was used to recruit families from rural and semirural communities in the Northeastern USA with children at 18 months of age and whose incomes were below the national median but above the poverty threshold. We targeted children in this income range for the larger aim of the study, which was to investigate the role of language development in ER. In terms of ER, associations between income and ER are thought to depend on caregiving quality (e.g., Raver, 2004).

Families were contacted through community leaders and events, birth announcements, and word of mouth, resulting in 124 families at time 1 (child age 18 months). By the final time point, at child age 48 months, 120 families (65 boys) remained enrolled. Retention methods included increasing compensation for each visit totaling $450 for eight visits, small gifts for children, and annual feedback on standardized child test results. The present study used data from six time points between child ages 18 and 48 months. Withdrawn families did not differ from those who completed on any demographic characteristic. Most (93.3 percent) children were identified as White by their mothers; 6.7 percent were biracial. At time 1, average household income was $40 502 (SD = 14 480.727), yielding an average income-to-needs ratio, an index of income relative to national norms, of 2.37 (SD = .94), with 1 = poverty and 3 = middle income. Most mothers completed high school (19.2 percent) and attended (21.7 percent) or completed college (36.7 percent). Most fathers completed high school (30.8 percent) and attended (23.3 percent) or completed college (26.7 percent).

Procedures

Annually parents completed questionnaires and home and lab visits. The present study used parent-report rating scales at child age 18, 30, and 42 months to measure child temperamental NA and EC. To measure child anger regulation, we used data from laboratory visits at child age 24, 36, and 48 months. Children and a parent (usually mothers) participated in laboratory visits, and each visit was of equivalent length and format, consisting of standard anger-eliciting tasks and non-challenging (relief) activities.

To assess anger regulation, the present study used one anger-eliciting task that was administered similarly at all ages, in which a child must wait to open a ‘surprise’ gift (Vaughn, Kopp,&Krakow, 1984). Only procedure materials, task instructions, and wall posters were in the room. The research assistant (RA) gave the mother ‘work’ (questionnaires) and the child a boring toy: one of a pair of cloth cymbals (24 months), a toy car with missing wheels (36 months), and a toy horse with missing legs (48 months). Mothers were instructed to behave as they normally would when they had to complete chores and needed their child to wait. Before leaving, the RA gave the child the boring toy and then placed a brightly wrapped bag on the child’s table, saying ‘This is a gift for you’. After 8 min, the RA returned, and the mother let the child open the gift. This task has been used to study young children’s anger expressions and regulatory behaviors (e.g., Cole, Teti, & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Silk, Shaw, Skuban, Oland, & Kovacs, 2006).

Anger Regulation

Two independent behavioral observation systems were used to create anger regulation variables. Using video recordings from the waiting task, two teams independently assessed the (1) intensive and temporal characteristics of child anger expressions and (2) temporal characteristics of two child-initiated regulatory behaviors. Each team was trained to at least 80 percent accuracy with master coders. The training period occurred over a period of four to six weeks for the emotion team and six to eight weeks for the regulatory behavior team; reliability was estimated on 15 percent of cases for each system. The details of each coding system are provided below.

Anger Expression

Based on previous studies, children’s emotional expressions during the waiting task were coded in 15-s epochs. Coders used an established system (Cole, Zahn-Waxler, & Smith, 1994) that uses facial and vocal cues (e.g., furrowed brow, square mouth, plosive, harsh voice tone) to infer anger. Across ages, the average k for emotion = .88 (range .81–.94). To generate anger expression variables thought to index ER (Thompson, 1990), the following steps were taken. Firstly, anger bouts were identified, with a bout defined as a set of contiguous 15-s epochs in which the child’s facial and/or vocal cues met criteria for anger. Secondly, coders rated the intensity of observed anger expressions on a scale from 1 (faint/minimal) to 3 (clearly visible). For analyses, average anger intensity was calculated as the sum of all intensity ratings divided by the number of anger bouts. Anger latency was calculated as the number of 15-s epochs that occurred prior to the first observation of anger and average anger duration as all epochs in which anger was observed divided by the total number of anger bouts.

Regulatory Behavior

Child regulatory behavior was independently coded in the same 15-s epochs. Based on a literature review (e.g., Mangelsdorf, Shapiro, & Marzolf, 1995), the coding system included seven behaviors commonly defined as regulatory attempts. The present study focused on two child-initiated behaviors that are widely considered to be adaptive in the context of a delay task involving a blocked goal: (1) distraction, shifting attention from a restricted object to an alternative, appropriate activity that did not involve the gift or mother (e.g., playing with the boring toy), and (2) calm bids, approaching the mother about the challenge of waiting (e.g., ‘I can open it when you are done, right?’). The average kappa across ages was κ = .82 (range .73–.91).A bout of regulatory behavior was defined by a set of contiguous 15-s epochs in which a child-initiated distraction or calm bid was observed. If both behaviors occurred within one 15-s epoch, each received a score of 1. Bouts were calculated in the same manner as anger expressions, as were calculations for latency and average duration variables.

Child Temperament

The 105-item toddler behavior assessment questionnaire-revised (TBAQ-R; Goldsmith, 1996) was completed by mothers at child age 18 and 30 months. Its counterpart for older children, the child behavior questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hersey, & Fisher, 2001), was completed at child age 42 months. Mothers rated items describing child behavior in the past two weeks on a 7-point scale, ranging from 1 (extremely untrue) to 7 (extremely true). The two higher-order factor scores for reactive and regulatory dimensions of temperament were used: NA [NA = mean of the scale scores for anger, sadness, social fearfulness, and soothability (reversed)] and EC (EC = mean of the scale scores for attention focusing, attention shifting, and inhibitory control). The EC factor at 42 months comprised attention focusing and inhibitory control (CBQ does not include attention shifting due to child’s age). At the age of 18 months, α for NA and EC were acceptable at .81 and .82, respectively; α at the age of 30 months were .86 and .88, and at the age of 42 months, .74 and .78.

Results

Overview of Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for all study variables are presented in Table 1. At the ages of 18, 30, and 42 months, there were child temperament data for 116, 114, and 116 children, respectively; missing data were due to the mothers losing or returning questionnaires too late. At the age of 24, 36, and 48 months, there were observational ER data for 117, 116, and 114 children; missing data were due to a missed lab visit (N = 3) or experimenter administration error. Missing data were estimated using maximum likelihood (ML) in multilevel modeling.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Variables

| M | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child temperament measures (mother-report) | ||||

| 18 months effortful control (TBAQ-R) | 3.45 | .55 | 2.04 | 4.75 |

| 18 months negative affectivity (TBAQ-R) | 4.03 | .56 | 2.75 | 5.50 |

| 30 months effortful control (TBAQ-R) | 3.57 | .54 | 2.27 | 4.96 |

| 30 months negative affectivity (TBAQ-R) | 4.37 | .60 | 3.11 | 5.81 |

| 42 months effortful control (CBQ) | 4.01 | .62 | 2.76 | 5.48 |

| 42 months negative affectivity (CBQ) | 4.58 | .86 | 1.78 | 6.33 |

| Child anger regulation measures (laboratory-observations) | ||||

| 24 months measures | ||||

| Anger bout intensity | 2.22 | .78 | 0 | 3.00 |

| Anger bout duration | 6.00 | 8.36 | 0 | 32.00 |

| Anger bout latency | 4.11 | 7.50 | 0 | 32.00 |

| Distraction bout duration | 1.95 | 1.40 | 0 | 9.33 |

| Distraction bout latency | 10.34 | 9.83 | 0 | 1.49 |

| Calm bid bout duration | .76 | .76 | 0 | 3.00 |

| Calm bid bout latency | 19.57 | 12.41 | 0 | 32.00 |

| 36 months measures | ||||

| Anger bout intensity | 1.52 | .92 | 0 | 3.00 |

| Anger bout duration | 1.87 | 1.91 | 0 | 14.50 |

| Anger bout latency | 10.08 | 11.46 | 0 | 32.00 |

| Distraction bout duration | 2.44 | 1.92 | 0 | 14.00 |

| Distraction bout latency | 7.25 | 8.32 | 0 | 32.00 |

| Calm bid bout duration | 1.32 | .60 | 0 | 3.67 |

| Calm bid bout latency | 6.26 | 9.43 | 0 | 32.00 |

| 48 months measures | ||||

| Anger bout intensity | .95 | .85 | 0 | 3.00 |

| Anger bout duration | 1.20 | 1.47 | 0 | 7.33 |

| Anger bout latency | 18.04 | 12.56 | 0 | 32.00 |

| Distraction bout duration | 3.56 | 3.24 | 0 | 31.00 |

| Distraction bout latency | 3.23 | 4.82 | 0 | 30.00 |

| Calm bid bout duration | 1.60 | .81 | 0 | 5.00 |

| Calm bid bout latency | 3.84 | 8.52 | 0 | 32.00 |

Note Bout duration = average number of epochs in bout; bout latency = number of epochs to first occurrence. TBAQ-R = toddler behavior assessment questionnaire-revised; CBQ = child behavior questionnaire.

Log transformations were used to normalize the left-skewed distributions for latency and duration variables for parametric analyses. Maternal ratings of child NA and EC at the three ages were significantly correlated with each other (Table 2); however, levels of child NA and EC varied across time (Figure 1), reinforcing the need to examine within-person changes in temperament. Bivariate correlations between mothers’ ratings of NA and EC and observed anger and strategy variables (see Table 3) indicated few and inconsistent associations across age points.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations among Maternal Ratings of Child Temperament at the Ages of 18, 30, and 42 months

| 18-month-old child temperament |

30-month-old child temperament |

42-month-old child temperament |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA | EC | NA | EC | NA | EC | |

| 18-month-old child temperament (TBAQ-R) | ||||||

| NA | — | |||||

| EC | −.52** | — | ||||

| 30-month-old child temperament (TBAQ-R) | ||||||

| NA | .68** | −.38** | — | |||

| EC | −.43** | .66** | −.51** | — | ||

| 42-month-old child temperament (CBQ) | ||||||

| NA | .45** | −.26** | .58** | −.36** | — | |

| EC | −.31** | .50** | −.40** | .68** | −.33** | — |

TBAQ-R = toddler behavior assessment questionnaire-revised; CBQ = child behavior questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of Child Temperamental Negative Affectivity and Effortful Control from the Age of 18 to 42 Months.

Note: Dotted line represents the sample mean score at each age.

Table 3.

Pearson Correlations among Maternal Ratings of Child Temperament and Temporal Characteristics of Observed Anger Regulation at each Age Point

| 18-month-old child temperament |

30-month-old child temperament |

42-month-old child temperament |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA | EC | NA | EC | NA | EC | |

| Age of 24 months anger regulation | ||||||

| Anger intensity | −.07 | −.00 | .01 | −.08 | .15 | .13 |

| Anger duration | −.03 | .04 | .04 | −.07 | .05 | .16* |

| Anger latency | −.06 | .08 | −.02 | .17* | −.15 | .17* |

| Distraction duration | .01 | .11 | −.16 | .03 | −.07 | .02 |

| Distraction latency | .08 | −.18* | .08 | −.08 | .03 | −.15 |

| Calm bid duration | .12 | −.17* | .10 | −.10 | .02 | .09 |

| Calm bid latency | −.13 | −.01 | −.18* | .12 | −.22** | .06 |

| Age of 36 months anger regulation | ||||||

| Anger intensity | −.08 | −.18** | .03 | −.05 | .08 | −.26** |

| Anger duration | .12 | −.24** | .11 | −.15 | .06 | −.14 |

| Anger latency | .07 | .12 | −.06 | .15 | −.11 | .27** |

| Distraction duration | .12 | .05 | .04 | .05 | .02 | .07 |

| Distraction latency | .02 | −.15 | .08 | .08 | .04 | −.10 |

| Calm bid duration | −.02 | −.02 | .01 | −.06 | .07 | −.07 |

| Calm bid latency | −.13 | −.01 | −.18* | .12 | −.22** | .06 |

| Age of 48 months anger regulation | ||||||

| Anger intensity | .02 | −.03 | .03 | .05 | .07 | −.11 |

| Anger duration | −.09 | .10 | −.13 | .16 | −.09 | .04 |

| Anger latency | −.03 | .14 | −.05 | .02 | −.10 | .19* |

| Distraction duration | .05 | .07 | .02 | .07 | −.10 | .04 |

| Distraction latency | −.12 | −.01 | −.03 | −.09 | −.05 | −.16* |

| Calm bid duration | .12 | −.03 | .19* | −.00 | .16* | −.03 |

| Calm bid latency | −.13 | −.01 | −.18* | .12 | −.22** | .06 |

Note: Duration and latency anger regulation variables are log transformed.

p < .01,

p < .05.

Seven growth curve models, also known as multilevel models, were used to test relations between temperament and anger regulation variables over time. Growth curve models were used to assess both individual differences (between-person differences) and intra-individual change (within-person variation) in temperamental NA and EC as predictors of child anger regulation. To examine relations between intra-individual change in temperament and anger regulation, fixed effects of time (defined months in study) and within-person NA and EC variables (centered at the age of 18 months) were entered as time-varying predictors at level 1. Level 2 (time-invariant level) examined between-person differences in mean levels of NA and EC. That is, for level 2, each child’s NA and EC scores were averaged across three time points (18, 30, and 42 months) and centered at the grand mean to create an age-aggregated individual score. This method of accounting for level 2 effects in order to study change over time is regarded as the best practice (Hoffman & Stawski, 2009; Kreft, de Leeuw, & Aiken, 1995).

A bottom-up approach to model building (e.g., Hoffman & Stawski, 2009) was used to identify the best-fitting model. We first estimated the unconditional (baseline) growth models for age-related changes in seven variables (anger intensity, anger latency and average duration, calm bid and distraction latencies and average durations) from 24 to 48 months. The ML statistic was used to estimate model parameters and the significance of random effects, and the Satterthwaite method was used to estimate degrees of freedom. Because individuals may vary in initial level and rate of change for indices of anger regulation, we tested whether models should include a random intercept (i.e., variation in initial level) and slope (i.e., variation in rate of change).

Next, time-varying NA and EC variables (centered at the age of 18 months or 0 months in study) were entered at level 1 to test effects of within-person changes in temperamental reactivity and regulation, and age-aggregated NA and EC variables (centered at the grand mean) were entered at level 2 to test effects of between-person differences in mean levels of temperament. Level 2 also included covariates. Specifically, child gender, maternal education, and family income-to-needs ratio were included as covariates of interest; however, the ER literature did not support a priori hypotheses. Evidence of gender differences in anger expression are reported in some studies (e.g., Chaplin, Cole, & Zahn-Waxler, 2005), but gender is not always tested and findings vary. Income effects on self-regulation, studied mainly in urban poor families, appear to depend on caregiving quality (Garner & Spears, 2000).

The last steps tested effects of both level 1 and level 2 temperament predictors on the slope of growth models by including time-by-temperament interaction terms. Next, NA-by-EC terms were added to test temperament interaction effects. Models were refined by removing all non-significant interactions. However, non-significant level 2 predictors associated with significant level 1 predictors were retained to ensure that only level 1 predictors accounted for within-person variance. Akaike and Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC) were used to compare model fits, where smaller AIC and/or BIC numbers indicate a better fit to the data (Singer & Willett, 2003).

Age-related Changes in Anger Expression and Regulatory Behaviors

Generally, the best-fitting unconditional (baseline) growth curve models for each anger regulation variable indicated improvement in anger regulation over early childhood (Table 4). Previous findings from this sample (Cole et al., 2011) revealed that from the age of 18 to 48 months, children’s anger was expressed more slowly and for shorter periods, and their use of distraction and calm bids became quicker and lasted longer. The present study examined whether child temperament predicted these age-related changes. Intra-class correlations (ICC) were calculated to confirm the presence of significant within- and between-person variance in anger regulation variables. ICCs indicated significant, albeit relatively low, level 2 between-person variance for anger intensity (24 percent), duration (17.7 percent), and latency (23 percent), likely because within-person change was included in the model. Similarly, the between-person variance for calm bid duration and latency were 6 and 13.8 percent, respectively, and for distraction, 14.3 percent (duration) and 7.5 percent (latency).

Table 4.

Baseline Growth Curve Models for Intensive and Temporal Characteristics of Anger Regulation

| Intensity |

Bout duration (lg) |

Latency to 1st bout

(lg) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | t value | Est | SE | t value | Est | SE | t value | |

| Anger expression | |||||||||

| Fixed effects of time | |||||||||

| Intercept (the age of 18 months) | 2.52 | .09 | 28.08*** | .74 | .03 | 10.57*** | .25 | .05 | .64*** |

| Linear slope | −.05 | .00 | −13.34** | −.02 | .00 | −11.43*** | .03 | .01 | 11.18*** |

| Covariance estimates | |||||||||

| Intercept | .17 | .05 | Z = 3.53*** | .01 | .01 | Z = 2.67*** | .06 | .02 | Z =3.24*** |

| Residual | .52 | .05 | Z = 10.95*** | .07 | .01 | Z = 10.95*** | .21 | .02 | Z =10.95*** |

| Model fit | |||||||||

| REML deviance | 1529.0 | 115.4 | 527.2 | ||||||

| AIC | 1537.1 | 129.4 | 535.3 | ||||||

| BIC | 1548.4 | 146.5 | 546.2 | ||||||

| Distraction | |||||||||

| Fixed effects of slope | |||||||||

| Intercept (the age of 18 months) | .38 | .02 | 17.88*** | .98 | .04 | 22.55*** | |||

| Linear slope | .01 | .00 | 6.33*** | −.02 | .00 | 7.99*** | |||

| Covariance estimates | |||||||||

| Intercept | .01 | .01 | Z = 17.88*** | .01 | .01 | ns | |||

| Residual | .03 | .03 | Z = 10.95*** | .14 | .01 | Z =10.95*** | |||

| Model fit | |||||||||

| REML deviance | −149.0 | 362.1 | |||||||

| AIC | −141.9 | 370.2 | |||||||

| BIC | −120.9 | 381.5 | |||||||

| Calm bids to mother | |||||||||

| Fixed effects of time | |||||||||

| Intercept (the age of 18 months) | .72 | .09 | 8.03*** | 1.16 | .05 | 22.55*** | |||

| Linear time | .04 | .00 | 9.89*** | −.03 | .00 | 12.42*** | |||

| Covariance estimates | |||||||||

| Intercept | .04 | .04 | ns | .02 | .01 | Z =1.75* | |||

| Residual | .62 | .62 | Z = 10.95*** | .20 | .02 | Z =10.95*** | |||

| Model fit | |||||||||

| REML deviance | 870.0 | 480.2 | |||||||

| AIC | 878.7 | 488.3 | |||||||

| BIC | 890.0 | 499.6 | |||||||

Note: lg = Log Transformed; Est = Estimate; SE = Standard Error; AIC = Akaike’s information criteria; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; REML = residual maximum likelihood.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p <.05,

ns = not significant.

Changes in Anger Expression as a Function of NA and EC

Anger Expression

As expected, between-person (age-aggregated) differences in EC predicted latency to anger at each age, with higher EC predicting a longer onset to anger, AIC = 521.4, BIC = 543.5, estimate = .15, F(1, 119) = 4.73, p < .01. Anger duration was predicted by a covariate, income-to-needs ratio; more economic strain predicted longer anger bouts, AIC = 119.3, BIC = 141.4, estimate = −.04, F(1, 112) = 4.48, p <.05. Contrary to predictions, neither within- nor between-person NA predicted any anger expression variable. No temperament or covariate predictors were associated with anger intensity.

Changes in Regulatory Efforts as a Function of NA and EC

Distraction

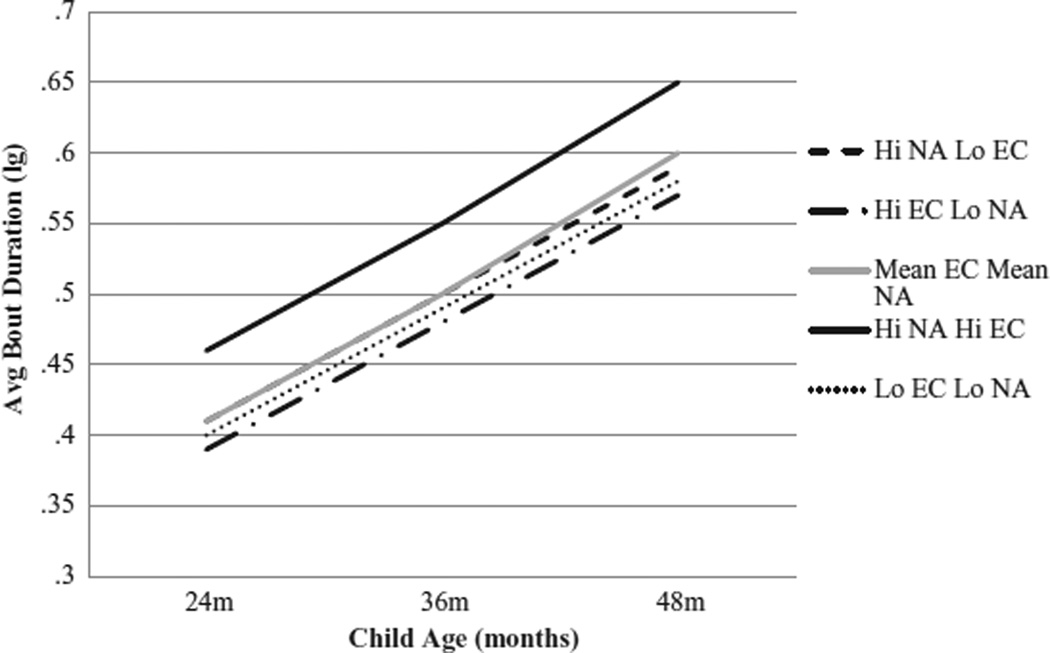

As predicted, within-person change in NA predicted age-related changes in the duration of distractions, AIC = −147.7, BIC = −122.8, estimate = −.05, F(1, 340) = 4.87, p <.05. Specifically, relative to children whose NA increased relative to their 18 months level, children whose NA declined sustained distractions longer at each age (Figure 2). Moreover, the expected interaction of NA and EC as a between-person difference was found, estimate = .03, F(1, 113) = 3.95, p < .05. Children with higher levels of age-aggregated NA and EC, as compared with other children, distracted themselves for longer periods (Figure 3). Finally, as expected, between-person differences in EC predicted how quickly children first distracted themselves, AIC = 357.1, BIC = 379.3, estimate = -.12, F(1, 126) = 6.40, p < .05. That is, higher levels of EC were associated with quicker use of distraction. However, contrary to prediction, within-person changes in EC did not predict distraction duration or latency.

Figure 2.

Within-person Effects of Child Negative Affectivity on Age-related Changes in the Average Duration of Children’s Distraction in the Waiting Task.

Note: ↓NA = children who decreased in NA relative to their initial ratings at the age of 18 months; ↑NA = children who increased in NA relative to their initial ratings at the age of 18 months.

Figure 3.

Between-person Effects of a NA × EC Interaction on Age-related Changes in the Average Duration of Children’s Distractions in the Waiting Task.

Note: Interaction involves between-person differences in child temperamental NA and EC, aggregated across age.

Calm Bids to Mother

Between-person differences in NA and EC were not associated with age-related changes in calm bid duration, but within-person changes in NA predicted changes in how quickly children bid calmly to mothers over time. Specifically, after accounting for family income-to-needs, the interaction of within-person NA and time was significant, AIC = 452.7, BIC = 480.4, estimate = −.02, F(1, 291) = 4.86, p < .05; however, income-to-needs was not a significant predictor. The interaction of within-person NA and time indicated that children whose NA increased over time had steeper declines in calm bid latency than those whose NA decreased, an unexpected finding. This effect occurred at 36 but not 48 months (Figure 4). Neither between-person differences nor within-person changes in EC were significantly associated with age-related changes in calm bid latency.

Figure 4.

Effects of Within-person Changes in Negative Affective on Age-related Changes in the Latency of Children’s Calm Bids to Mother in the Waiting Task.

Note: ↓NA = children who decreased in NA relative to their initial ratings at the age of 18 months; ↑NA = children who increased in NA relative to their initial ratings at the age of 18 months.

Discussion

The present study investigated relations between two temperament dimensions, reactivity (NA) and regulation (EC), and changes in children’s anger regulation from the ages of 24 to 48 months. Given that NA and EC appear to change in early childhood, we examined the effects of temperament as between-person individual differences (age-aggregated means) and within-person changes from the ages of 18 to 42 months. Results indicated that higher mean levels of EC predicted longer latency to anger and quicker use of distraction. Also, between-person differences in child NA and EC interacted to predict the duration of children’s distractions. Finally, within-person, age-related decreases in NA predicted how quickly children calmly bid for support and how long they distracted themselves.

Effortful Control

As suggested by theory (Calkins, 1994), higher mean levels of early childhood EC predicted slower anger onsets and quicker use of distraction during a wait for a desired object. Thus, EC was positively associated with children’s ability to forestall anger, perhaps because EC enables quickness in the ability to distract oneself from the object. It was surprising, however, that EC did not predict age-related increases in the duration of distractions. Although previous studies report relations between EC and young children’s attention control in experimental tasks (e.g., Gerardi-Caulton, 2000), those tasks differ from the quasi-naturalistic waiting task. That is, tasks assessing children’s use of attentional control for resolving spatial conflict are not intended to elicit negative emotion. The ability to direct attention away from something that is desired (i.e., an attractively wrapped gift) may require further development of executive attention, suggesting that the role of EC in supporting self-distraction should be explored in studies that extend beyond the early preschool years. Another reason for the lack of relation between parent-reported EC and the duration of children’s observed distractions may be that parents are less attuned to subtleties like the temporal parameters of regulatory behaviors—an issue about level of analysis that has not been studied. Increases in the duration of child distractions over early childhood are significant but small (Cole et al., 2011). Such important micro changes may differ from the level of analysis parents use when judging their child’s characteristics across contexts and times. Nevertheless, the present findings are the first to highlight the potential role of EC in children’s improved ability to quickly use distraction over the course of early childhood.

Negative Affectivity

Longitudinal studies have shown relations between infant temperamental NA and toddler anger expression, as well as preschool-aged NA and school-aged socioemotional functioning (see Eisenberg et al., 2010). The present findings are the first to show a longitudinal relation between decreases in child NA and increases in the length of time that children use distraction during a pivotal period in the development of self-regulation (Kopp, 1982). This lends support for the view that the normative development of regulatory behaviors may be hindered when children do not show the expected, normative declines in NA (Posner & Rothbart, 2000). Moreover, findings suggest a possible mechanism for this hindrance, specifically that increasing or stably high levels of NA detrimentally affect children’s ability to engage attentional control (Fox & Calkins, 2003).

Notably, the interaction of between-person differences in EC and NA predicted age-related increases in the length of time that children sustained distractions in the waiting task. Specifically, higher levels of age-aggregated EC and NA were associated with longer distractions, consistent with the hypothesis that higher EC supports ER regardless of NA level. Yet, it was surprising that children with higher EC and lower NA did not show the longest distractions. This finding may indicate that children with higher NA sustain longer distractions if they also have higher EC, perhaps because their greater reactivity provides more opportunity for practicing self-regulation whereas their higher EC supports those efforts. However, the significant effect of within-person changes in NA on distraction duration may mean that higher NA is associated with improved use of distraction only if children’s NA declines over early childhood.

Age-related decreases in NA predicted children’s use of calm bids in a somewhat complicated manner. As expected, children whose NA decreased over time were quicker to calmly bid to their mother than children whose NA increased, at least through the age of 36 months. However, there was no difference in latency to bid by the age of 48 months. Children’s strategies for regulating emotion become more autonomous during early childhood such that they rely less on external sources of regulation like seeking adult support (Mangelsdorf et al., 1995). In the present study, children’s calm bids were defined by a child-seeking maternal support to cope with waiting. As such, calm bids were less autonomous regulatory efforts than distractions. Therefore, as compared with those whose NA increased, children whose NA declined may have been less reliant on external sources of support when regulating emotion at earlier ages. These findings again highlight the potential importance of decreases in child reactivity for advances in children’s ER behaviors.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study relied on one laboratory procedure to assess anger regulation. Although mothers in the present study indicated the laboratory wait was meaningful in capturing their children’s strengths and weaknesses and that it tapped a common situation (asking a child to wait for something), the value of a regulatory behavior depends on situational context. Distraction is effective when one must wait for something desirable or tempting (Sethi, Mischel, Lawrence, Shoda,&Rodriguez, 2000) but may not be effective when a child has to solve a problem. In addition, anger-eliciting procedures involving blocked goals likely elicit both involuntary and deliberate regulatory efforts, complicating our ability to understand age-related changes in children’s effortful attempts at ER. To more fully understand the influences of parental perceptions of child temperament on children’s regulatory efforts, future research might consider using a variety of self-control tasks that assess children’s responses to blocked goals, as well as their responses to other contextual demands. Study findings are also limited by the fact that the direction of effects between parent-reported temperament and observations of child anger regulation cannot be determined. For instance, changes in children’s anger regulation may have influenced changes in maternal perceptions of child temperament; however, we have tried to account for this by the timing of our assessments.

Finally, results are based on a lower-income, non-urban sample, which may limit the generality of the findings. The majority of studies relating child temperament and ER are conducted with highly educated and advantaged families. The present study addresses a gap in the literature by examining an underrepresented (rural to semirural) population experiencing economic strain. In the present study, income was only predictive of the duration of children’s anger expressions. Given that income was unrelated to any other measure of anger regulation and that this sample is still understudied, the development of ER in children from families in non-urban regions requires further study. Moreover, given evidence that care giving quality moderates relations between low socioeconomic status and child ER (Garner & Spears, 2000), future studies on the development of ER in at-risk populations could benefit from considering the unique effects of economic strain and those associated with correlates of low income such as at-risk parenting or low levels of parental education.

The findings from the present study can inform future studies of child temperament and ER. This is the first study to support the view that both individual differences in EC and intra-individual changes in NA are associated with age-related changes in young children’s observed ER behaviors. The null results highlight the inherent challenges in studying multidimensional, related constructs that change over time. This challenge may be best met by developmental cascade models delineating pathways among changes in various aspects of child temperament and self-regulation. Nevertheless, this study is the first to show prospective associations between mother-reported temperament and observations of young children’s actual anger expressions and use of regulatory strategies, during the period when deliberate regulation of anger is thought to emerge.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by two grants to the authors from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH061388 and T32MH070327). A special thank you is extended to the children and families who dedicated their time to this project.

References

- Belsky J, Friedman SL, Hsieh K. Testing a core emotion-regulation prediction: Does early attentional persistence moderate the effect of infant negative emotionality on later development? Child Development. 2001;72:123–133. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braungart-Reiker JM, Stifter CA. Infants’ responses to frustrating situations: Continuity and change in reactivity and regulation. Child Development. 1996;67:1767–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA, Goldsmith HH. Fear and anger regulation in infancy: Effects on the temporal dynamics of affective expression. Child Development. 1998;69:359–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD. Origins and outcomes of individual differences in emotion regulation. The Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:53–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE. Physiological and behavioral regulation in two-year-old children with aggressive/destructive behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:103–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1005112912906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Dedmon SE, Gill KL, Lomax LE, Johnson LM. Frustration in infancy: Implications for emotion regulation, physiological processes, and temperament. Infancy. 2002;3:175–197. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Johnson MJ. Toddler regulation of distress to frustrating events: Temperamental and maternal correlates. Infant Behavior and Development. 1998;21:379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Campos JJ, Frankel CB, Camras L. On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development. 2004;75:377–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C. Parental socialization of emotion expression: Gender differences and relations to child adjustment. Emotion. 2005;5:80–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Martin SE, Dennis TA. Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development. 2004;75:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Tan PZ, Hall SE, Zhang Y, Crnic KA, Blair CB, et al. Developmental changes in anger expression and attention focus during a delay: Learning to wait. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1078–1089. doi: 10.1037/a0023813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Teti LO, Zahn-Waxler C. Mutual emotion regulation and the stability of conduct problems between preschool and early school age. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Zahn-Waxler C, Smith DK. Expressive control during a disappointment: Variations related to preschoolers’ behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective style and affective disorders: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Sheffield-Morris A. Children’s emotion-related regulation. Advances in Child Development and Behavior. 2003;30:189–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, Eggum ND. Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:495–525. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. The effect of maternal depression on maternal ratings of child behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:245–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00917534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Calkins SD. The development of self-control of emotion: Intrinsic and extrinsic influences. Motivation and Emotion. 2003;27:7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner BM, Spinrad TL, Eisenberg N. Focused attention in toddlers: Measurement, stability, and relations to negative emotion and parenting. Infant and Child Development. 2008;17:339–363. doi: 10.1002/ICD.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Spears FM. Emotion regulation in low income preschoolers. Social Development. 2000;9:246–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gerardi-Caulton G. Sensitivity to spatial conflict and the development of self-regulation in children 24–36 months of age. Developmental Science. 2000;3:397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH. Studying temperament via construction of the toddler behavior assessment questionnaire. Child Development. 1996;67:218–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Buss AH, Plomin R, Rothbart MK, Thomas A, Chess S, et al. Roundtable: What is temperament? Four approaches. Child Development. 1987;58:505–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J. Laboratory assessment of temperament—Preschool version. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Calkins SD, Keane SP. Sustained attention development during the toddlerhood to preschool period: Associations with toddlers’ emotion regulation strategies and maternal behavior. Infant and Child Development. 2011;20:389–408. doi: 10.1002/icd.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanish LD, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad TL, Ryan P, Schmidt S. The expression and regulation of negative emotions: Risk factors for young children’s peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:335–353. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Soderlund AL, Braungart-Rieker JM. Early individual differences in temperamental reactivity and regulation: Implications for effortful control in early childhood. Infant Behavior and Development. 2008;31:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L, Stawski RS. Persons as contexts: Evaluating between-person and within-person effects in longitudinal analysis. Research in Human Development. 2009;6:97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Coy KC, Murray KT. The development of self-regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development. 2000;72:1091–1111. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Regulation of distress and negative emotions: A developmental view. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:343–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft IGG, de Leeuw J, Aiken LS. The effect of different forms of centering in hierarchical linear models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1995;30:1–21. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf SC, Shapiro JR, Marzolf D. Developmental and temperamental differences in emotional regulation in infancy. Child Development. 1995;66:1817–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Kerr DC, Lopez NL, Wellman HM. Developmental foundations of externalizing problems in young children: The role of effortful control. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:25–45. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:427–441. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400003096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC. Placing emotional self-regulation in sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts. Child Development. 2004;75:346–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hersey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: The children’s behavior questionnaire. Child Development. 2001;72:1394–1408. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Lerner R, editors; Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th ed. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley Press; 2006. pp. 99–166. (Series Eds.), (Vol. Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Sheese BE. Temperament and emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, Thompson RA, editors. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ziaie H, O’Boyle CG. Self-regulation and emotion in infancy. In: Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, editors. New directions for child and adolescent development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1992. pp. 7–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda MR, Posner MI, Rothbart MK. Attentional control and self-regulation. In: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi A, Mischel W, Lawrence AJ, Shoda Y, Rodriguez ML. The role of strategic attention deployment in development of self-regulation: Predicting preschoolers’ delay of gratification from mother–toddler interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:767–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Shaw DS, Skuban EM, Oland AA, Kovacs M. Emotion regulation strategies in offspring of childhood-onset depressed mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:69–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Supplee LH, Skuban EM, Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS, Stoltz E. Preschool boys’ development of emotional self-regulation strategies in a sample at risk for behavior problems. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2011;172:95–120. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2010.510545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion and self-regulation. In: Thompson RA, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation, 1998: Socioemotional development. Current theory and research in motivation. Vol. 36. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1990. pp. 367–467. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. The development of emotion regulation: Biological and behavioral considerations. In: Fox NA, editor. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. Serial No. 240. Vol. 59. 1994. pp. 25–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn BE, Kopp CB, Krakow JB. The emergence and consolidation of self-control from eighteen to thirty months of age: Normative trends and individual differences. Child Development. 1984;55:990–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]