Abstract

Purpose: One in 4 persons living with HIV/AIDS is an older adult (age 50 or older); unfortunately, older adults are disproportionately diagnosed in late stages of HIV disease. Psychological barriers, including belief in AIDS-related conspiracy theories (e.g., HIV was created to eliminate certain groups) and mistrust in the government, may influence whether adults undergo HIV testing. We examined relationships between these factors and recent HIV testing among at-risk, older adults. Design and Methods: This was a cross-sectional study among older adults enrolled in a large venue–based study. None had a previous diagnosis of HIV/AIDS; all were seeking care at venues with high HIV prevalence. We used multiple logistic regression to estimate the associations between self-reported belief in AIDS-related conspiracy theories, mistrust in the government, and HIV testing performed within the past 12 months. Results: Among the 226 participants, 30% reported belief in AIDS conspiracy theories, 72% reported government mistrust, and 45% reported not undergoing HIV testing within the past 12 months. Belief in conspiracy theories was positively associated with recent HIV testing (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 1.94, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.05–3.60), whereas mistrust in the government was negatively associated with testing (OR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.26–0.73). Implications: Psychological barriers are prevalent among at-risk older adults seeking services at venues with high HIV prevalences and may influence HIV testing. Identifying particular sources of misinformation and mistrust would appear useful for appropriate targeting of HIV testing strategies.

Key Words: Age groups, AIDS serodiagnosis, Community health services, Prevention and control, Vulnerable populations

One in four persons living with HIV/AIDS is an older adult (age 50 or older); unfortunately, older adults with HIV infection are disproportionately diagnosed in late stages of HIV disease (Zingmond et al., 2001). Late diagnosis is associated with rapid progression to AIDS, the end-stage condition of HIV infection (Martin, Fain, & Klotz, 2008; Zingmond et al., 2001). Some 43% of HIV-positive persons aged 50–55 years and 51% of those aged 65 years or older develop AIDS within a year of receiving an HIV diagnosis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011b). Older adults also account for a disproportionate share (35%) of all AIDS-related deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006, 2008a). The increasing share of HIV infections, rapid progression to AIDS, and high mortality rates suggest at-risk older adults experience barriers to early diagnosis of HIV infection. Unless abated, the public health significance of these trends is likely to grow as the U.S. older adult population, which is made up primarily of Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964), continues to expand rapidly.

Early detection of undiagnosed HIV infection is essential for optimizing long-term prognosis, controlling the comorbid conditions that are common among older adults in general (e.g., cardiovascular disease) (Auerbach, 2003; Lekas, Schrimshaw, & Siegel, 2005), and reducing the risk of progression to AIDS (Cohen et al., 2011). To facilitate early diagnosis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that anyone who engages in known risk behaviors automatically undergo HIV testing when seeking health services in settings where the prevalence of undiagnosed infection typically exceeds that of the mainstream population, as it does, for example, in sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics (Branson et al., 2006). CDC further recommends that higher risk persons, such as sexually active adults and injection drug users, undergo testing at least annually (Branson et al., 2006). Relative to mainstream segments of the population, people who seek services in high HIV prevalence venues typically are more socially vulnerable (i.e., persons whose income, education, age, and/or experiences with discrimination leave them with fewer resources to address health and other problems) (Bohnert & Latkin, 2009; Hutchinson et al., 2007; Roberts, Newman, Duan, & Rudy, 2005; Whetten-Goldstein & Nguyen, 2002) and more likely to acquire or transmit HIV (Kates & Levi, 2007).

HIV testing is readily available in venues where many socially vulnerable older adults receive services. Nevertheless, some avoid or delay HIV testing, which is the point of entry for HIV/AIDS services and treatment (Tangredi, Danvers, Molony, & Williams, 2008). One study (Harawa, Leng, Kim, & Cunningham, 2011) based on a nationally representative sample of nearly 3,000 older adults found that less than 20% had ever undergone HIV testing and less than 6% had ever been advised by a provider to do so (Harawa et al., 2011).

An array of complex factors may influence HIV testing among older adults. Barriers to testing include stigma (Emlet, 2006; Poindexter & Shippy, 2010), isolation, denial, and patient or provider misperceptions (Lindau et al., 2007) that older adults have minimal risk for HIV infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008b; Emlet, 2006; Lekas et al., 2005; Savasta, 2004). Perceived HIV risk tends to be low among older adults; therefore, actual risk behaviors may better indicate the need for testing in targeted screening. However, routine testing ensures that all persons undergo testing regardless of perceived risk.

Older adults, especially those in higher HIV-prevalence groups, do engage in behaviors known to transmit HIV (e.g., having sex without condoms, sharing needles to inject drugs) (Boeri, Sterk, & Elifson, 2008; Lindau et al., 2007; Neundorfer, Harris, Britton, & Lynch, 2005; Richard, Bell, & Montoya, 2000; Waite, Laumann, Das, & Schumm, 2009). For instance, approximately 1,600 White, 450 Black, and 300 Latino men aged 50 or older acquired HIV in 2009 through unprotected sex with other men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011a). In other research conducted among senior-housing residents, investigators learned that 42% of residents had been sexually active within the previous six months. One third of the sexually active residents reported two or more partners during that period, but only 20% had regularly used condoms (Schensul, Levy, & Disch, 2003).

Both misconceptions about HIV/AIDS—specifically, a belief in AIDS-related conspiracy theories (ACTs)—and mistrust in the government may influence the likelihood of HIV testing. ACTs reflect suspicions people hold about the origin of HIV/AIDS and the reasons it disproportionately affects poor and minority communities. One ACT example is the belief that HIV was created by scientists or the government to eliminate certain groups. Since the beginning of the epidemic, studies (Bogart & Thorburn, 2005; Herek & Capitanio, 1994; Klonoff & Landrine, 1999) conducted among population-based, racially/ethnically diverse populations have suggested that at least 25% of these populations endorse ACTS or mistrust the government (Guinan, 1993; Quinn, 1997). In general, ACTs have been inversely associated with HIV prevention–related outcomes such as condom use (Bogart & Bird, 2003; Bogart, Galvan, Wagner, & Klein, 2010; Bogart & Thorburn, 2005, 2006; Hutchinson et al., 2007; Kalichman, 2009). Most of this research has been conducted among African Americans; however, studies conducted among substance abusers, members of diverse racial/ethnic groups, and socially vulnerable populations (Herek & Capitanio, 1994; Roberts et al., 2005; Ross, Essien, & Torres, 2006) have reported similar findings. Even more widespread than a belief in ACTs is mistrust in the government, specifically, that it cannot be counted on to care for socially vulnerable populations. Few studies have examined the influence of a more generalized mistrust of government on HIV preventive behaviors. One such study (Herek & Capitanio, 1994) found that 37% of whites and 43% of African Americans in a nationally representative, random sample did not trust the government to disclose information to the public about HIV/AIDS. The study did not examine the implications for HIV testing. The impact of government mistrust is logically the greatest for people who rely on the government for public services or health care.

Belief in ACTs and mistrust in the government may uniquely influence HIV testing behavior among older adults because their life spans encompass both the beginning of the HIV epidemic, when AIDS was most highly stigmatized (Rosenfeld, Bartlam, & Smith, 2012), and periods in U.S. history when overt discrimination was socially acceptable, even legal. Before the mid-1960s, for instance, it was neither illegal nor socially unacceptable for providers to refuse care to people based on race (Byrd & Clayton, 2002). Few studies explore these issues among older adults at risk for HIV infection. We targeted this gap in knowledge by (a) estimating the proportion of older adults in high-HIV-prevalence venues who had recently undergone HIV testing, (b) determining the proportions who believe in ACTs and/or mistrust the government, and (c) examining how these factors are associated with self-reports of HIV testing.

Conceptual Framework

The study was guided by the Behavioral Model of Healthcare Utilization (known as the “access to care” model), which is widely used to explain factors influencing individuals’ behaviors in clinical settings (Andersen, 1995; Andersen & Newman, 1973). According to our application of the model, HIV testing is determined most proximally by three types of population characteristics: Factors predisposing people to undergo testing (e.g., demographic characteristics), factors enabling access to services (e.g., having a usual source of care), and factors indicating a need for services (e.g., risk category). HIV testing prevalence is not well documented in this population; therefore, we first calculated the proportion of sample members recently undergoing HIV testing. Belief in ACTs and mistrust in the government were the factors of particular interest and are considered (negative) enabling factors. We hypothesized inverse associations between belief in ACTs or mistrust in the government and recently undergoing HIV testing; specifically, the odds of testing would be lower for those reporting belief in ACTs compared with those not reporting such beliefs and would be lower for those with high levels of mistrust in the government relative to those with lower levels of mistrust.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study. It assessed levels of HIV testing and examined relations between self-reported belief in ACTs, mistrust in the government, and HIV testing within the past 12 months among 226 older adults (aged more than 50 years) participating in the LA VOICES study. LA VOICES was a large study conducted among socially vulnerable, racially/ethnically diverse men and women (N = 1,302) in Los Angeles to identify factors influencing willingness to accept an HIV vaccine if one becomes available. The details of the study design have been previously published (Newman et al., 2009). Briefly, a representative sample of participants was recruited from three types of public health venues that provide HIV testing: STD clinics (n = 12), needle-exchange sites (n = 8), and Latino health clinics (n = 8). Using a three-stage sampling strategy, the investigators randomly selected: (a) venues within specified geographic areas, (b) 4-hr blocks of time within each venue, and (c) adults seeking services during each selected block of time. Data were collected from August 2006 to May 2007.

Research staff recruited participants upon presentation for services. Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 years, no previous diagnosis of HIV infection, and not employed at the venue. Participants provided informed consent and completed in-person, computer-assisted interviews during their visit. They received $20 remuneration for their time. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, and University of Toronto institutional review boards.

Sample

The analysis was limited to LA VOICES participants who were at least 50 years old (n = 233). The present study sample (N = 226) excluded seven persons who lacked data regarding their belief in ACTs or mistrust in the government.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable, HIV testing within the past 12 months, was calculated based on the date of recruitment and self-reported date of the most recent HIV test. It was coded 1 to indicate testing in the past year and 0 to indicate not undergoing testing in the past year.

Independent Variables

The main independent variables were belief in ACTs and mistrust in the government. Belief in ACTs was assessed using a validated four-item scale, Cronbach’s alpha (α) = .84 (Bogart, Wagner, Galvan, & Banks, 2010). Response options were on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with an additional option for refusal to answer. The government mistrust scale was from the American National Election Studies (The American National Election Studies [ANES], 2011). It had three items and a modest reliability, Cronbach’s α = .63. Response options were on a four-point Likert-type scale for the first two items and a three-point Likert-type scale for the third; each item also contained an option for refusal to answer. Mean scores for both scales were an unweighted average of the item responses, which could range from 1.0 to 4.0 for belief in ACTs and from 1.0 to 3.7 for mistrust in government. Higher scale scores indicated stronger belief in ACTs and higher levels of mistrust, respectively.

Sex was self-reported as male or female. A single item classed racial/ethnic identity as Hispanic/Latino, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black or African American, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, “other” race/ethnicity, or multiple racial/ethnic backgrounds. Participants who indicated “other” race/ethnicity or multiple backgrounds named those backgrounds in a follow-up, open-ended item and were categorized accordingly.

HIV risk category was assessed using two binary variables indicative of elevated risk for HIV infection: men who have sex with other men and injection drug use. Higher risk was determined by comparing participants’ own sex versus the reported sex(es) of sexual partners and from an array of items assessing prior drug use behaviors.

We adapted an existing measure (DeHart and Birkimer, 1997) to capture perceived HIV risk. The variable was assessed using an eight-item summative scale (Cronbach’s α = .59), with response options on a Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Response values were transformed to a standardized 100-point scale in which higher scores reflected higher perceived risk of acquiring HIV.

Educational attainment was an ordinal variable with options of less than high school, high school diploma or General Educational Development, some college, and college degree or higher.

Additional measures included the demographic characteristics of monthly income and employment status (full time, part time, or unemployed/retired/disabled); HIV knowledge based on the number of correct responses out of eight items that were summed and transformed to a continuous scale with scores ranging from 0 (no knowledge) to 1 (high knowledge); having a usual source of care (yes/no); the type of place where one usually obtains health care (private physician, hospital, emergency department, other place, refusal to answer); health insurance status (private, public, or no insurance); level of trust (Schuster et al., 2005) in one’s provider (a six-item summative scale with response options on a five-point Likert-type scale); and other HIV testing-related factors, which included any previous testing for HIV and testing preference (rapid testing, traditional testing, or self-administered, in-home testing).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were obtained to explore the nature of missing data, data normality, potential interactions (by race, sex, and venue), and potential confounding. The analysis involved multiple logistic regression with generalized estimating equations. This method accounts for the complex survey design and clustering of variances that occurs when participants recruited from one venue are more similar to each other than they are to participants from other venues (Stokes, Davis, & Koch, 2000). Due to the small sample size, the main analysis did not include factors from the conceptual model that were not significant in the preliminary analyses. We used a nonautomatic, backward-elimination modeling process. The initial (full) model contained both scales (belief in ACTs and mistrust in government) and the predisposing (race/ethnicity, sex, education), enabling (usual source/place of care), and need (HIV risk category) factors. To obtain the final adjusted model, we systematically examined the contributions of each covariate to the overall model and removed variables that neither confounded the main relationship of interest nor provided additional information to the model. Data analysis was completed using Stata statistical software version 10 (Stata Corporation, 2007).

Results

This section summarizes key sample characteristics by testing status, levels of belief in ACTs and mistrust in the government, characteristics associated with belief in ACTs and mistrust in the government, and estimates of the associations between belief in ACTs or mistrust in the government and undergoing HIV testing.

Nearly half of the sample (44.7%) reported not undergoing HIV testing within the past 12 months. More than a quarter (26.5%) reported never being tested for HIV (not shown). Participants ranged in age from 50 to 85 years, with the mean age similar for those who did and did not undergo recent testing (Table 1). Women accounted for 58.6% of Hispanic participants but only 21.8% of whites, 18.2% of blacks, and 27.5% of those self-reporting “other” race (not shown). Most participants (50.9%) were enrolled at needle-exchange sites, 37.2% at Latino health clinics, and the remainder (12.0%) at STD clinics. Overall, 80% of participants had a usual source of care; however, fewer than one in four usually obtained care from a private physician. Perceived HIV risk scores were similar across testing status, ranging from 25.0 to 70.8 among nontesters and 0.0 to 83.3 among testers on the 100-point scale. HIV knowledge scores were similar across testing status, too, ranging from 0.3 to 0.9 among nontesters and 0.2 to 0.9 among testers on this 0–1 scale (not shown).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics. Overall and by Self-Reported HIV Testing Performed Within the Previous 12 Months

| Overall sample(N = 226) | Testing within previous 12 months | p Valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 101) | Yes (n = 125) | |||

| Predisposing factors | ||||

| Mean age (SD) | 56.1 (5.1) | 56.3 (5.5) | 56.0 (4.8) | .74 |

| Sex, % (n) | .01 | |||

| Female | 35.4 (80) | 44.6 (45) | 28.0 (35) | |

| Male | 64.6 (146) | 55.4 (56) | 72.0 (90) | |

| Race/ethnicity, % (n) | <.01 | |||

| Hispanic | 46.5 (105) | 65.3 (66) | 31.2 (39) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 18.1 (41) | 14.8 (15) | 20.8 (26) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 25.2 (57) | 13.9 (14) | 34.4 (43) | |

| Other race | 10.2 (23) | 5.9 (6) | 13.6 (17) | |

| Mean monthly income, $ (SD)b | 1,884 (8,140) | 2,486 (11,921) | 1,390 (2,025) | .36 |

| Employment status, % (n) | .77 | |||

| Unemployed | 27.9 (63) | 27.7 (28) | 28.0 (35) | |

| Full time | 17.3 (39) | 19.8 (20) | 15.2 (19) | |

| Part time | 13.3 (30) | 13.9 (14) | 12.8 (16) | |

| Other status | 41.6 (94) | 38.6 (39) | 44.0 (55) | .77 |

| Educational attainment, % (n) | <.01 | |||

| <High school | 39.8 (90) | 51.5 (52) | 30.4 (38) | |

| High school diploma | 27.4 (62) | 25.7 (26) | 28.8 (36) | |

| Some college | 23.9 (54) | 17.8 (18) | 28.8 (36) | |

| College degree or higher | 8.9 (20) | 5.0 (5) | 12.0 (15) | |

| Enabling factors | ||||

| Venue, % (n) | <.01 | |||

| STD clinic | 12.0 (27) | 5.9 (6) | 16.8 (21) | |

| Needle-exchange site | 50.9 (115) | 31.7 (32) | 66.4 (83) | |

| Latino public health clinic | 37.2 (84) | 62.3 (63) | 16.8 (21) | |

| Usual source of care, % (n) | .22 | |||

| Lack usual source of care | 19.5 (44) | 15.8 (16) | 22.4 (28) | |

| Have usual source of care | 80.5 (182) | 84.2 (85) | 77.6 (97) | |

| Place of usual care, % (n)c | <.01 | |||

| Private physician | 22.8 (46) | 22.0 (20) | 23.4 (26) | |

| Clinic | 53.0 (107) | 67.0 (61) | 41.4 (46) | |

| Hospital, emergency room, other | 24.3 (49) | 11.0 (10) | 35.1 (39) | |

| Health insurance, % (n) | .05 | |||

| Uninsured | 47.4 (107) | 56.4 (57) | 40.0 (50) | |

| Public insurance | 36.7 (83) | 30.6 (31) | 41.6 (52) | |

| Private insurance | 15.9 (36) | 12.9 (13) | 18.4 (23) | |

| HIV knowledge, mean (SD)d | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) | .07 |

| Need factors | ||||

| Perceived HIV risk, mean (SD) | 49.5 (12.1) | 49.8 (10.1) | 49.2 (13.5) | .33 |

| Risk category, % (n) | ||||

| Injected drug use within past 30 days | 38.1 (86) | 23.8 (24) | 49.6 (62) | <.01 |

| Men having sex with men | 9.7 (22) | 6.9 (7) | 12.0 (15) | .20 |

Note: SD = standard deviation; STD = sexually transmitted disease.

aComparison of tested versus not tested participants.

bExcludes two participants missing data on monthly income.

cExcludes those who did not report a usual source of care (n = 24).

dExcludes one participant missing data on HIV knowledge.

Compared with tested participants, the group reporting no testing within the previous 12 months included significantly higher proportions of women, Hispanic persons, those who did not complete high school, those enrolled at Latino health clinics, those not receiving usual care from a private physician or clinic, and recent injection drug users. Health insurance was of borderline significance (p = .05), with the nontested group including a larger proportion of uninsured participants compared with the tested group.

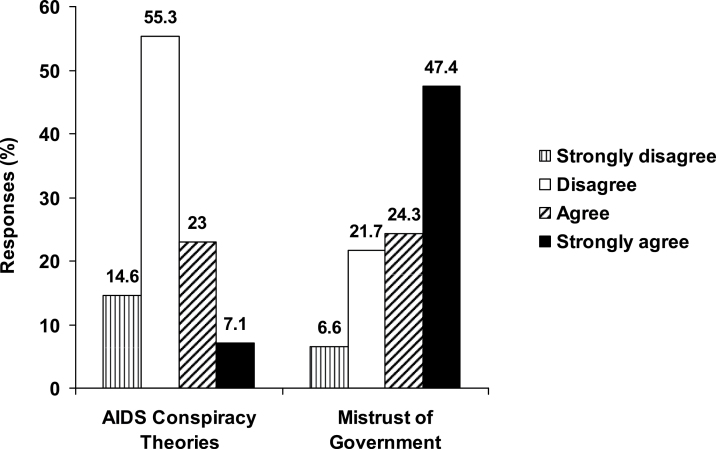

About 30% of the sample agreed or strongly agreed on average with (i.e., endorsed) the four ACTs (Figure 1); 7% of the sample reported strong agreement with items on this scale. More than 70% of the sample agreed or strongly agreed on average with the three items on the government mistrust scale; nearly half the sample strongly agreed with the items on the scale, which indicated very high levels of mistrust. In the bivariate analysis, participants who reported no recent HIV test had a significantly lower mean score on the ACT belief scale and a nonsignificantly higher mean score on the government mistrust scale compared with tested participants (Table 2). In particular, tested participants had significantly higher scale scores for the two items assessing the belief that HIV/AIDS is being used to eliminate certain groups.

Figure 1.

Distribution of responses to items assessing belief in AIDS-related conspiracy theories and mistrust in government.

Table 2.

AIDS-Related Conspiracy Theory and Mistrust in Government by Self-Reported HIV Testing Performed Within the Previous 12 Months

| Testing within previous 12 months | % Difference (p) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 101) | Yes (n = 125) | ||

| Mean scale scores (SD)a | |||

| AIDS conspiracy theory belief scale | 2.2 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | +9% (.03) |

| Government mistrust scale | 2.8 (0.1) | 2.7 (0.1) | −4% (.12) |

| Conspiracy and mistrust items, mean (SD)b | p | ||

| AIDS conspiracy theory items | |||

| The government already has an AIDS vaccine but is keeping it from the public | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.6 (0.1) | .07 |

| Sometimes I think the government is using AIDS to kill off people who are not wanted by society | 2.1 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.1) | .01 |

| There is a cure for AIDS, but the government is keeping it from the public | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | .20 |

| HIV is a manmade virus created to get rid of certain groups of people | 2.1 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | .03 |

| Government mistrust itemsb | |||

| How much of the time do you think you can trust the government to do what is right? | 2.8 (0.1) | 2.7 (0.1) | .50 |

| Would you say the government is pretty much run by a few big interests looking out for themselves or that it is run for the benefit of all the people?c | 3.0 (0.1) | 2.8 (0.1) | .20 |

| In terms of people running the government, do you think quite a few are crooked, not very many are crooked, or hardly any are crooked?c | 2.6 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | .10 |

aScores range from 1.0 to 3.7 for government conspiracy and from 1.0 to 4.0 for AIDS conspiracy theory beliefs, with higher scores indicating stronger endorsement of beliefs.

bResponse options range from 1 to 4 except for the final government mistrust item, for which response options range from 1 to 3. Higher scores indicate higher mean levels of agreement with the statement.

cInverse coded so that higher values reflect stronger endorsement of beliefs.

In unadjusted modeling, belief in ACTs was associated with a higher likelihood of reported recent HIV testing (odds ratio [OR] = 1.86 per one-point increase in scale score; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.03–3.34) (Table 3). Mistrust in the government was associated with a lower likelihood of recent HIV testing (OR = 0.71 per one-point increase in scale score; 95% CI = 0.45–1.11), but the association was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Associations Between Participant Characteristics and Self-Reported HIV Testing Performed Within the Previous 12 Months

| Variable | Unadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (full) model | Final model | ||

| AIDS conspiracy theory belief scale scorea | 1.86 (1.03–3.34) | 1.81 (0.96–3.43) | 1.94 (1.05–3.60) |

| Government mistrust scale scorea | 0.71 (0.45–1.11) | 0.43 (0.24–0.75) | 0.43 (0.26–0.73) |

| Race (referent = white) | |||

| Black | 2.63 (0.57–12.2) | 1.66 (0.43–6.38) | |

| Hispanic | 0.48 (0.15–1.56) | 0.31 (0.11–0.91) | |

| Other race | 1.43 (0.31–6.57) | 1.30 (0.32–5.26) | |

| Male sex (referent = female) | 1.72 (0.71–4.19) | 1.70 (0.77–3.78) | |

| Risk category (referent = no) | |||

| Men having sex with men | 0.91 (0.30–2.75) | 0.95 (0.37–2.45) | |

| Injection drug use within past 30 days | 2.11 (0.86–5.15) | 2.39 (1.12–5.10) | |

| Education (referent = some college or more) | |||

| <High school | 0.62 (0.27–1.41) | ||

| High school diploma or GED | 0.91 (0.33–2.46) | ||

| Place of usual care (referent = private physician) | |||

| Clinic | 0.84 (0.29–2.42) | ||

| Hospital | 1.76 (0.37–8.30) | ||

| Emergency room or other | 1.89 (0.26–13.62) | ||

Note: GED = General Education Development; CI = confidence interval.

aPer one-point increase.

Covariates from the conceptual model that were not significant in preliminary analyses were age, income, employment status, usual source of care, insurance status, HIV knowledge, and perceived HIV risk. In the multivariable analysis, place of usual care and educational attainment also dropped out. The final model included ACT beliefs and government mistrust, race/ethnicity, sex, and risk category. It had slightly more extreme point estimates and greater precision than the unadjusted estimates. The odds of recent HIV testing were 94% higher for each one-point increase in ACT belief scale score (95% CI = 5–360 higher; Table 3). On the other hand, for every one-point increase in the government mistrust scale score, the odds of recent testing decreased by 57% (95% CI = 26–73).

Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence of HIV testing, reported belief in ACTs and mistrust in the government among socially vulnerable, at-risk older adults who were seeking care in public health venues that provide HIV testing, and examined relations between such beliefs and self-reported HIV testing performed within the previous 12 months. There were three main findings. Overall, HIV testing was low (55%) considering the sample was recruited from venues in which HIV prevalence is relatively high. Nearly, a third of the sample reported belief in ACTs; more than two thirds mistrusted the government.

Main Findings

That nearly half the sample had not undergone testing for HIV infection within the past 12 months indicated many missed opportunities to test older, at-risk adults in these venues. One reason for the low levels of testing may be that the CDC’s HIV testing recommendations do not apply to people aged 65 or older (Branson et al., 2006; Tangredi et al., 2008; Waite et al., 2009). In LA VOICES, 8% of all participants were 65 or older. Excluding these oldest at-risk adults from routine testing could impede early HIV detection for those with the greatest risk of complications if diagnosed late (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011a; Kirk & Goetz, 2009).

Contrary to our hypothesis, belief in ACTs was associated with higher, not lower, odds of testing. This suggests that some at-risk, older adults respond to ACTs by proactively engaging in preventive behaviors such as routine HIV testing. They may undergo testing more often to try to avoid the threats to personal safety described in many AIDS conspiracies. Proactive responses of this sort have been documented previously. For instance, many gay men of the Baby Boom generation, which is the same cohort to which the present findings are generalizable, became AIDS activists because they wanted to halt the epidemic’s devastating impact on their communities (Rosenfeld et al., 2012). Our finding suggests that despite—or, perhaps because of—their social vulnerability, at-risk older adults may choose to exercise agency and draw on resilience in responding to some perceived social inequalities. Similar patterns were observed in a study among African American patients at STD clinics: Those who perceived racial discrimination as pervasive had higher odds of HIV testing (Ford et al., 2009).

As hypothesized, mistrust in the government was associated with lower odds of testing. This suggests that older adults who harbor government mistrust may obtain some services in public health venues but avoid or delay undergoing HIV testing there. This is unfortunate because routine HIV testing in these venues could facilitate early diagnosis and better management of the comorbid conditions that are increasingly common among HIV-positive older adults (Chu & Selwyn, 2011; Linsk, Fowler, & Klein, 2003). The levels of government mistrust observed in this sample may reflect high levels of government mistrust in the broader society (Zeleny & Thee-Brenan, 2011). If so, the implications are particularly salient for older adults, especially those who seek care in public health venues. Public health venues are government entities. Ongoing efforts to increase HIV testing are largely based in these venues. Our findings suggest that alternative venues or strategies may be needed to facilitate HIV testing among those who mistrust the government.

The reason ACTs increased testing while government mistrust decreased it may be due to whether individuals believe there are specific actions they can take to counter each concern. For people who endorse ACTs, regularly undergoing routine HIV testing is one way to confirm their HIV-negative status or ensure that any undiagnosed HIV infection is detected as early as possible. In contrast, those who mistrust the government may feel there is little they can do in response to this concern except, perhaps, to avoid regularly HIV testing in public health venues.

Additional Findings

Neither perceived HIV risk nor HIV knowledge was associated with testing. This observation, which is consistent with several previous studies (Adams et al., 2003; Ford, Daniel, & Miller, 2006; Kellerman et al., 2002), may reflect the tendency of providers and older adults to underestimate HIV risk in this population (Linsk et al., 2003). Though we were unable to examine whether age-based stereotypes (Emlet, 2006) explain the low levels of perceived risk and HIV knowledge, these findings underscore why routinely testing all patients is more appropriate than risk-based assessments for identifying undiagnosed HIV infections.

Compared with others in our sample, a smaller proportion of Latino participants reported undergoing recent HIV testing. Many had been recruited from Latino health clinics that conduct HIV testing. Although HIV prevalence may be lower in these clinics than in STD clinics or needle-exchange sites, 6% of participants recruited from these clinics were HIV positive (Kinsler et al., 2009). Limited acculturation (Kinsler et al., 2009), undocumented citizenship status, and religious affiliation may be barriers to HIV testing among some Latinos. Data on immigration status and religious affiliation were not available, but future research should account for these important factors. Understanding cultural and other determinants of HIV testing among Latinos is important to meet the needs of this growing population; however, asking socially vulnerable persons about their immigration status requires considerable sensitivity because many fear deportation or other legal actions.

The proportions reporting belief in ACTs did not vary significantly by race/ethnicity; however, the reasons for holding the beliefs may differ across groups. Among African Americans, endorsements of ACTs stem from historical experiences with U.S. racism and medical discrimination (Klonoff & Landrine, 1999; Northington Gamble, 1997; Quinn, 1997; Thomas & Curran, 1999). Although knowledge of African Americans’ experiences may lead members of other racial/ethnic groups to endorse ACTs, groups’ unique experiences with social inequalities and maltreatment also shape their beliefs (Ford & Harawa, 2010). Therefore, future research should explore how specific inequalities, such as those experienced during immigration (Viruell-Fuentes, 2007), contribute to the endorsement of ACTs among other populations (e.g., Latinos).

Implications for Research

Most research on factors such as belief in ACTs, mistrust in government, and discrimination focus on the implications for risk behaviors such as drug use. Our findings underscore the need to better understand the implications for preventive behaviors such as routine testing (Dailey, Kasl, Holford, & Jones, 2007) and to understand how resilience might enhance testing in this population. Research should also clarify whether government mistrust influences older adults’ health care decision making and utilization more generally.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The study has three implications for policy and practice. First, because participants were recruited from venues that provide HIV testing and health services, the low levels of testing represent missed opportunities for early diagnosis. The prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection is higher in these venues than in other health care settings (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009), and many of the services (e.g., distributing clean needles to injection drug users) are only useful if individuals engage in known risk behaviors. Therefore, regardless of age, it is appropriate to presume HIV risk and encourage HIV testing for anyone presenting for these services.

Second, it may be necessary to expand standard HIV prevention messages to address misconceptions and mistrust. Persons who mistrust the government are unlikely to disclose this to their providers. Therefore, providers and health educators must use strategies that account for potential mistrust even if patients do not mention it as a concern.

Third, although levels of government mistrust may be high in society in general, the implications for HIV diagnosis may be particularly salient for older adults who obtain services at public health venues. Expanding HIV testing in nonpublic health venues (e.g., community-based organizations) may be one way to increase testing among those who mistrust the government.

Limitations and Strengths

Several considerations should be kept in mind when reviewing these findings. This is a cross-sectional study; therefore, the relationships reported here cannot be considered causal in nature. Some participants who agree with statements such as “sometimes I think the government is using AIDS to kill off people who are not wanted by society” may have underreported their true level of agreement with the statements because they did not want the interviewer to think they held extreme beliefs. This would lead to underestimation of the prevalence of belief in ACTs and misestimation of the association with HIV testing. Self-reported rates of HIV testing may be much greater than actual rates of HIV testing (Phillips & Catania, 1995). Taken together, these considerations suggest that the true association between belief in ACTs and recent HIV testing may be larger than that reported here.

Strengths of the study include LA VOICES’ representative sampling strategy, which enhances the generalizability of the findings. This aspect of the study contrasts sharply with much of the prior research, which has been constrained, often by necessity, to convenience or very small samples. The study’s focus on older adults and on outpatients in high HIV-prevalence venues extends this line of inquiry to populations that may be both more socially vulnerable and more likely than mainstream segments of the population to acquire or transmit undiagnosed HIV.

In conclusion, greater attention to HIV testing among at-risk older adults is warranted. Many who seek services in public health venues do not undergo testing for HIV infection, which might be due to mistrust in the government. Making HIV testing routine in public health venues may be an efficient way to improve early diagnosis among at-risk older adults. Alternative possibilities include expanding HIV testing in nonpublic health venues. Finally, identifying particular sources of misinformation and mistrust would appear useful for appropriate targeting of HIV testing strategies.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (5 RO1 MH069087 to W. E. Cunningham and P. A. Newman); the National Institute on Aging (P30-AG02-1684 to C. L. Ford) through funding provided to the Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research and the UCLA Center for Health Improvement for Minority Elders (CHIME); the University of California at Los Angeles AIDS Institute and Center For AIDS Research (AI028697 to C. L. Ford); a seed grant from the California Center for Population Research (5R24HD041022 to C. L. Ford); and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH 5K01MH085503 to S.-J. Lee). Dr. W. E. Cunningham also received partial support by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R01 DA030781) and NIMH (R34 MH089719) for his work on this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Phyllis Autry for her very insightful feedback on an early draft of this article, as well as Jessica Gipson, Deborah Mindry, and two anonymous reviewers for additional comments.

References

- Adams A. L., Becker T. M., Lapidus J. A., Modesitt S. K., Lehman J. S., Loveless M. O. (2003). HIV infection risk, behaviors, and attitudes about testing: Are perceptions changing? Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 30, 764–768. 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000078824.33076.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R. M. (1995). Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 1–10. 10.2307/2137284 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R. M., Newman J. F. (1973). Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society, 51, 95–124. 10.2307/3349613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach J. D. (2003). HIV/AIDS and aging: Interventions for older adults. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 33,(Suppl), S57–S58. 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeri M. W., Sterk C. E., Elifson K. W. (2008). Reconceptualizing early and late onset: A life course analysis of older heroin users. Gerontologist, 48, 637–645. 10.1093/geront/48.5.637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L. M., Bird S. T. (2003). Exploring the relationship of conspiracy beliefs about HIV/AIDS to sexual behaviors and attitudes among African-American adults. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95, 1057–1065 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2594665/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L. M., Galvan F. H., Wagner G. J., Klein D. J. (2010). Longitudinal association of HIV conspiracy beliefs with sexual risk among Black males living with HIV. AIDS & Behavior, 15(6), 1180–1186.10.1007/s10461-010-9796-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L. M., Thorburn S. (2005). Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 38, 213–218. 10.1097/00126334-200502010-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L. M., Thorburn S. (2006). Relationship of African Americans’ sociodemographic characteristics to belief in conspiracies about HIV/AIDS and birth control. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98, 1144–1150 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2569474/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L. M., Wagner G., Galvan F. H., Banks D. (2010). Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 53, 648–655.10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c57dbc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert A. S., Latkin C. A. (2009). HIV testing and conspiracy beliefs regarding the origins of HIV among African Americans. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23, 759–763.10.1089/apc.2009.0061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson B. M., Handsfield H. H., Lampe M. A., Janssen R. S., Taylor A. W., Lyss S. B., Clark J. E. (2006). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports: Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports/Centers for Disease Control, 55, 1–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd W. M., Clayton L. A. (2002). An American health dilemma: Race, medicine, and health care in the United States, New York, NY: Routledge [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006). Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS—United States, 1981–2005 Retrieved April 1, 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index2006.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008a). HIV prevalence estimates—United States, 2006 Retrieved April 1, 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index2008.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008b). HIV/AIDS among persons aged 50 and older Retrieved April 1, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/over50/resources/factsheets/over50.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2009). Late HIV testing—34 states, 1996–2005 Retrieved April 1, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index2009.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011a). CDC Fact Sheet: Estimates of new HIV infections in the United States, 2006–2009 Retrieved April 1, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/HIV-Infections-2006–2009.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011b). HIV Surveillance Report, 2009 Retrieved April 1, 2012, from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/

- Chu C., Selwyn P. A. (2011). An epidemic in evolution: The need for new models of HIV care in the chronic disease era. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 88, 556–566.10.1007/s11524-011-9552-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. M., Van Handel M. M., Branson B. M., Hall I. H., Hu X., Koenig L. J., et al. (2011). Vital signs: HIV prevention through care and treatment--United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 60, 1618–1623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dailey A. B., Kasl S. V., Holford T. R., Jones B. A. (2007). Perceived racial discrimination and nonadherence to screening mammography guidelines: Results from the race differences in the screening mammography process study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 165, 1287–1295. 10.1093/aje/kwm004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart D. D., Birkimer J. C. (1997). Trying to practice safer sex: Development of the sexual risks scale. Journal of Sex Research, 34, 11–25. 10.1080/00224499709551860 [Google Scholar]

- Emlet C. A. (2006). “You’re awfully old to have this disease”: Experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist, 46, 781–790. 10.1093/geront/46.6.781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Daniel M., Earp J. A. L., Kaufman J. S., Golin C. E., Miller W. C. (2009). Perceived everyday racism, residential segregation and HIV testing in an STD clinic sample. American Journal of Public Health, 99,(Supp), 137–143. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Daniel M., Miller W. C. (2006). High rates of HIV testing despite low perceived HIV risk among African-American sexually transmitted disease patients. Journal of the National Medical Association, 98, 841–844 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. L., Harawa N. T. (2010). A new conceptualization of ethnicity for social epidemiologic and health equity research. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 71, 251–258.10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinan M. E. (1993). Black communities’ belief in “AIDS as genocide”. A barrier to overcome for HIV prevention. Annals of Epidemiology, 3, 193–195. 10.1016/1047–2797(93)90136-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harawa N. T., Leng M., Kim J., Cunningham W. E. (2011). Racial/ethnic and gender differences among older adults in nonmonogamous partnerships, time spent single, and human immunodeficiency virus testing. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 38, 1110–1117.10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e614b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. M., Capitanio J. P. (1994). Conspiracies, contagion, and compassion: Trust and public reactions to AIDS. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education, 6, 365–375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson A. B., Begley E. B., Sullivan P., Clark H. A., Boyett B. C., Kellerman S. E. (2007). Conspiracy beliefs and trust in information about HIV/AIDS among minority men who have sex with men. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 45, 603–605. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181151262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S. C. (2009). Denying AIDS: Conspiracy theories, pseudoscience and human tragedy, New York, NY: Copernicus Books, Springer Science + Business Media [Google Scholar]

- Kates J., Levi J. (2007). Insurance coverage and access to HIV testing and treatment: Considerations for individuals at risk for infection and for those with undiagnosed infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 45,(Suppl. 4)S255–S260.10.1086/522547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman S. E., Lehman J. S., Lansky A., Stevens M. R., Hecht F. M., Bindman A. B., et al. (2002). HIV testing within at-risk populations in the United States and the reasons for seeking or avoiding HIV testing. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 31, 202–210. 10.1097/00126334-200210010-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsler J. J., Lee S.-J., Sayles J. N., Newman P. A., Diamant A., Cunningham W. E. (2009). The impact of acculturation on utilization of HIV prevention services and access to care among an at-risk hispanic population. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 20, 996–1011. 10.1353/hpu.0.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk J. B., Goetz M. B. (2009). Human immunodeficiency virus in an aging population, a complication of success. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57, 2129–2138.10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02494.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonoff E. A., Landrine H. (1999). Do Blacks believe that HIV/AIDS is a government conspiracy against them? Preventive Medicine, 28, 451–457. 10.1006/pmed.1999.0463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lekas H. M., Schrimshaw E. W., Siegel K. (2005). Pathways to HIV testing among adults aged fifty and older with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care, 17, 674–687. 10.1080/09540120412331336670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau S. T., Schumm L. P., Laumann E. O., Levinson W., O’Muircheartaigh C. A., Waite L. J. (2007). A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 762–774.10.1056/NEJMoa067423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsk N. L., Fowler J. P., Klein S. J. (2003). HIV/AIDS prevention and care services and services for the aging: Bridging the gap between service systems to assist older people. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 33,(Suppl. 2)S243–S250. 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00025 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C. P., Fain M. J., Klotz S. A. (2008). The older HIV-positive adult: A critical review of the medical literature. American Journal of Medicine, 121, 1032–1037. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neundorfer M. M., Harris P. B., Britton P. J., Lynch D. A. (2005). HIV-risk factors for midlife and older women. Gerontologist, 45, 617–625. 10.1093/geront/45.5.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman P. A., Lee S.-J., Duan N., Rudy E., Nakazono T. K., Boscardin J., et al. (2009). Preventive HIV vaccine acceptability and behavioral risk compensation among a random sample of high-risk adults in Los Angeles (LA VOICES). Health Services Research, 44(6), 2167–2179. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01039.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northington Gamble V. (1997). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 1773–1778. 10.2105/AJPH.87.11.1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips K. A., Catania J. A. (1995). Consistency in self-reports of HIV testing: Longitudinal findings from the National AIDS Behavioral Surveys. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974), 110, 749–753 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poindexter C. C., Shippy R. A. (2010). HIV diagnosis disclosure: Stigma management and stigma resistance. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 53, 366–381.10.1080/01634371003715841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn S. C. (1997). Belief in AIDS as a form of genocide: Implications for HIV prevention programs for African Americans. Journal of Health Education, 28,(Suppl. 6)S6–S11 [Google Scholar]

- Richard A. J., Bell D. C., Montoya I. D. (2000). Age and HIV risk in a national sample of injection drug and crack cocaine users. Substance Use and Misuse, 35, 1385–1404. 10.3109/10826080009148221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts K. J., Newman P. A., Duan N., Rudy E. T. (2005). HIV vaccine knowledge and beliefs among communities at elevated risk: Conspiracies, questions and confusion. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97, 1662–1671 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld D., Bartlam B., Smith R. D. (2012). Out of the closet and into the trenches: Gay male Baby Boomers, aging, and HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist, 52, 255–264. 10.1093/geront/gnr138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. W., Essien E. J., Torres I. (2006). Conspiracy beliefs about the origin of HIV/AIDS in four racial/ethnic groups. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 41, 342–344. 10.1097/ 01.qai.0000209897.59384.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savasta A. M. (2004). HIV: Associated transmission risks in older adults—an integrative review of the literature. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 15, 50–59. 10.1177/ 1055329003252051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul J. J., Levy J. A., Disch W. B. (2003). Individual, contextual, and social network factors affecting exposure to HIV/AIDS risk among older residents living in low-income senior housing complexes. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 33,(Suppl. 2)S138–S152. 10.1097/00126334-200306012-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster M. A., Collins R., Cunningham W. E., Morton S. C., Zierler S., Wong M., et al. (2005). Perceived discrimination in clinical care in a nationally representative sample of HIV-infected adults receiving health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20, 807–813.10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.05049.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corporation (2007). Stata for Windows (Version 10/SE), College Station, TX: Stata Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes M. E., Davis C. S., Koch G. G. (2000). Generalized estimating equations categorical data analysis using the SAS® System, (p. 254). Cary, NC: SAS Institute [Google Scholar]

- Tangredi L. A., Danvers K., Molony S. L., Williams A. (2008). New CDC recommendations for HIV testing in older adults. Nurse Practitioner, 33, 37–44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The American National Election Studies (ANES) (2011). The ANES guide to public opinion and electoral behavior Retrieved from http://www.electionstudies.org/studypages/cdf/anes_cdf_int.pdf Accessed March 28, 2012.

- Thomas S. B., Curran J. W. (1999). Tuskegee: From science to conspiracy to metaphor. American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 317, 1–4. 10.1097/00000441-199901000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes E. A. (2007). Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 1524–1535. 10.1016/ j.socscimed.2007.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite L. J., Laumann E. O., Das A., Schumm L. P. (2009). Sexuality: Measures of partnerships, practices, attitudes, and problems in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64,(Suppl. 1)i56–i66. 10.1093/geronb/gbp038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten-Goldstein K., Nguyen T. Q. (2002). “You’re the First One I’ve Told”: New faces of HIV in the South, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press [Google Scholar]

- Zeleny J., Thee-Brenan M. (2011, October 26). New poll finds a deep distrust of government, New York Times, p. A1 Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/26/us/politics/poll-finds-anxiety-on-the-economy-fuels-volatility-in-the-2012-race.html

- Zingmond D. S., Wenger N. S., Crystal S., Joyce G. F., Liu H., Sambamoorthi U., et al. (2001). Circumstances at HIV diagnosis and progression of disease in older HIV-infected Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1117–1120. 10.2105/AJPH.91.7.1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]