Abstract

Purpose

This study assessed the prevalence of convergence insufficiency (CI) with and without simultaneous vision dysfunctions within the traumatic brain injury (TBI) sample population because although CI is commonly reported with TBI, the prevalence of concurrent visual dysfunctions with CI in TBI is unknown.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of 557 medical records from TBI civilian patients was conducted. Patients were all evaluated by a single optometrist. Visual acuity, oculomotor, binocular vision function, accommodation, visual fields, ocular health and vestibular function were assessed. Statistical comparisons between the CI and non-CI, as well as in-patient and out-patient subgroups, were conducted using chi-squared and Z-tests.

Results

Approximately 9% of the TBI sample had CI without the following simultaneous diagnoses: saccade or pursuit dysfunction; 3rd, 4th, or 6th nerve palsy; visual field deficit; visual spatial inattention/neglect; vestibular dysfunction or nystagmus. Photophobia with CI was observed in 16.3% (N=21/130) and vestibular dysfunction with CI was observed in 18.5% (N=24/130) of the CI subgroup. CI and cranial nerve palsies were common and yielded prevalence rates of 23.3% (N=130/557) and 26.9% (N=150/557), respectively, within the TBI sample. Accommodative dysfunction was common within the non-presbyopic TBI sample with a prevalence of 24.4% (N=76/314). Visual field deficits or unilateral visual spatial inattention/neglect were observed within 29.6% (N=80/270) of the TBI in-patient subgroup and were significantly more prevalent compared to the out-patient subgroup (p<0.001). Most TBI patients had visual acuities of 20/60 or better in the TBI sample (85%;N=473/557).

Conclusions

CI without simultaneous visual or vestibular dysfunctions was observed in about 9% of the visually symptomatic TBI civilian population studied. A thorough visual and vestibular examination is recommended for all TBI patients.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, oculomotor dysfunction, binocular vision, convergence insufficiency, visual dysfunction, visual impairment, visual acuity, mechanism of injury, vestibular dysfunction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a growing public health problem. There are 1.7 million TBI cases diagnosed annually,1 of which 70-80% are classified as mild.2-6 TBI can result from motor vehicle accidents, falls, assault, strike or blows to the head, biking or sports accidents 7-16 as well as blast injuries from military conflict.17-22 The direct and indirect cost of TBI is about $60 billion1 annually, where 44% ($26.4 billion)23 is associated with mild TBI. The military population also has a considerable number of veterans with TBI -- the signature injury from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.24, 25 An estimated 320,000 personnel (19.5% of those deployed from 2001 to 2008) screened positive for a probable TBI, typically from blast injuries.26 The United States Department of Defense estimates that health care cost of TBI in the first year following deployment is about $900 million.26 Reports indicate that TBI resulting from combat in Afghanistan and Iraq will present major diagnostic, therapeutic and economic challenges for many years to come and many believe that the current statistics underestimate this epidemiological problem.27

It is often suggested that a diffuse injury can potentially affect many brain processes. A diffuse compared to a focal injury makes it challenging to understand the underlying neurophysiologic changes evoked from TBI. TBI may be associated with diffuse axonal injury (DAI), which may occur with or without a focal blunt force to the head.28, 29 Reviews from cellular studies explain the pathophysiological process, where trauma of acceleration / deceleration may lead to damage to the white matter and superficial layers of the brain. This damage may then extend inward within the brain, depending upon the extent of acceleration / deceleration forces. Initially, the injury disrupts the cytoskeletal network and axonal membranes of white matter and the surrounding cerebral vasculature.30-33 Secondary damage may occur due to ischemia and a cytotoxic cascade, including altered calcium homeostasis and oxygen depletion, leading to cell death.30-33 The recovery from TBI may be determined by the severity of these secondary injuries.32, 33 Some brain regions may be more at risk for mechanical injury during trauma than others.34 Given the presumed diffuse damage of TBI, it is not surprising that TBI manifests in a diverse array of motor, sensory, cognitive and / or emotional symptoms and disabilities, both short and long-term.35-39 Understanding the impaired brain-behavior as a result of TBI may be one of the best approaches to understanding complex brain processes.40

Over 50% of the brain is directly or indirectly involved in visual processes.41, 42 Visual dysfunctions are routinely observed after TBI and include oculomotor dysfunctions, binocular dysfunctions, visual field deficits, and / or reduced visual acuity.9, 16, 17, 43-47 It is estimated that a majority of TBI patients, approximately 60%, will have visual abnormalities, namely oculomotor, binocular vision and visual field deficits.9, 15-17, 43-47 Convergence insufficiency (CI), a type of binocular vision dysfunction, is an eye co-ordination and alignment problem which can result in visual symptoms when engaged in reading or performing other close work.48 CI is observed months to years post-injury, with prevalence rates ranging from 42% to 43% in civilian9, 44 and 46%17 in veteran TBI populations. Patients with CI report an array of asthenopic symptoms, including blurred vision, diplopia, eye strain, headaches, loss of concentration, having to reread and / or read slowly, difficulty in remembering what was read and visual fatigue.49-51 These symptoms may adversely affect daily activities, such as schoolwork52 and employment tasks,44 as well as the overall quality of life. Many patients participate in rehabilitation to reduce symptoms or improve visual performance; however, the underlying neuro-physiological basis for improvement in clinical signs and symptoms in CI patients is unknown. 53-57

The first aim of this study is to analyze the visual examination records of a large sample of TBI patients from both in-patient and out-patient care to quantify the type and frequency of visual and vestibular dysfunctions observed in a clinical setting. The second aim is to evaluate the prevalence of CI within TBI patients with and without simultaneous visual and vestibular dysfunctions. The percentage of concurrent visual and vestibular dysfunctions within the CI subgroup were compared for statistically significant differences compared to the non-CI subgroup within the TBI sample. This study is the first investigation to compare the CI and non-CI subgroup samples of TBI patients undergoing comprehensive visual examinations performed by an optometrist.

METHODS

The experimental design will be discussed in terms of the TBI population sample, the examination methods, and the rationale for the statistical analyses.

TBI Population Sample

The data were derived from records of TBI patients evaluated by one of the authors (V.R.V.), a licensed optometrist, who measured all clinical vision parameters for the analysis of this study. The present TBI sample represents approximately half of all neurologically impaired patients who were examined from January 1989 to February 2003 following referral by different neurologists. Other patients who were excluded from this analysis had a diagnosis of cerebral vascular accidents, multiple sclerosis, brain tumors, or progressive neurological dysfunctions. This study was approved by the NJIT and Kessler Institute Review Boards for an exemption pursuant to the U.S. Department of Human Health and Human Studies (HHS) article 45 CFR 46.l01(b)(4) because the study analyzed existing data that did not contain any personal identifiers. Of the TBI patients within this sample, 39% (N=219/557) were female and 61% (N=338/557) were male.

The in-patients with vision-based symptoms were predominantly referred from Kessler Institute of Rehabilitation (KIR) while a smaller proportion from John F. Kennedy Medical Center (JFKMC) and Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital (RWJUH) were also evaluated. All medical facilities were located within the state of New Jersey, USA. All out-patients with vision-based symptoms were evaluated in one of the author’s (V.R.V.) private practice located in Westfield, New Jersey, USA. The severity of TBI (mild, moderate or severe) was not available within the visual examination files. Instead, the typical Functional Independence Measurement (FIM) which is an assessment of functional capability and routinely used in many rehabilitation settings58, 59 reported within the last six months from the Kessler Institute was utilized to assess the average functional capabilities of in-patients upon admission compared to discharge into out-patient care.

Examination Methods

The visual examination included the following assessments: visual acuity, accommodation, binocular vision, visual oculomotor function, visual fields and ocular health. Visual acuity refers to the best-corrected level for that particular eye. Far and near visual acuity was assessed using the Snellen eye chart (Bernell BC-11931, Masawaka, IL, USA) located along midline 3 m / 10 ft and 40 cm / 16 inches away from the patient, respectively. If the patient had aphasia (acquired linguistic problems affecting letter identification), then the LEA symbol chart with pointing to matching symbols (Precision Vision, La Salle, IL, USA) was used to assess visual acuity. Static retinoscopy measured the refraction of the patients. Cycloplegia was not performed because accommodation and vergence function were assessed.

Accommodation was measured using the near point of accommodation, negative relative accommodation, positive relative accommodation, and accommodative convergence / accommodation (AC/A) ratio. The gradient AC/A ratio was calculated for each subject with a plano, +1.00 D, and -1.00D lens. 60-64 Dissociated phoria at far (3 m / 10 ft) and near (40 cm / 16 in) were measured using either the alternate cover test, cover / uncover test or Maddox Rod test. To determine the near point of convergence (NPC), a patient tracked a high-acuity visual stimulus slowly moving inward along midline. When the patient reported diplopia or when the optometrist observed a break in fusion, the NPC was measured as described in prior literature.65,66

Binocular vision was assessed by measuring the near point of convergence (NPC), fusional vergence reserve, and near dissociated phoria. The vast majority of patients were diagnosed with CI when the patient’s NPC was greater than 2.5 inches (6-7 cm) and did not meet Sheard’s criterion, which states that the fusional vergence reserve should be at least twice the magnitude of the near dissociated phoria (measured at 16 inches (40 cm) along midline).67 A small portion of this population (N=37/557 or 6.6%) did not have the cognitive ability needed for the optometrist to measure near dissociated phoria and fusional vergence reserve. For this small subset, CI was diagnosed using the NPC and cover testing at near. Only one patient (0.2% of this sample) was diagnosed with CI using NPC and cover testing at near. Strabismic patients with a secondary diagnosis of CI were excluded from this analysis. The Randot Stereopsis test (Bernell VTP, Misawaka, IN, USA) was used to assess third-degree fusion (binocular function).

Visual oculomotor function included the evaluation of smooth pursuit and saccadic eye movements. Patients were verbally instructed to follow the light of a transilluminator and / or track a single printed letter (5 mm2) depending upon the patient’s abilities and / or acuity limits to evaluate smooth pursuit and saccade responses. Smooth pursuit responses were assessed as 1) movements were smooth and accurate or 2) had one or more fixation losses. Saccadic eye movements were assessed as 1) smooth and accurate, 2) had gross undershooting or overshooting, or 3) the subject was unable to perform the task. 68-69, 70

Visual fields were analyzed using an optokinetic nystagmus (OKN) drum to assess the presence / absence of visual field correlates in both horizontal directions of rotation assessing potential asymmetries. Visual fields were assessed by confrontation analysis with single and double simultaneous presentation of targets to evaluate for unilateral visual spatial inattention / neglect, visual field deficits or both. In addition to confrontation testing, patients were observed for postural alterations and gaze preferences. Single and double simultaneous presentations were administered to all patients to differentiate those patients with: 1) unilateral spatial inattention / neglect; 2) visual field deficits; or 3) simultaneous inattention / neglect and visual field deficits. Depending upon patient functionality, visual fields were also assessed with a Humphrey Field Test (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA, USA).

The assessment of ocular health included an evaluation of the retina, internal ocular structures, corneal tear layer, and the pupillary response to light stimulation. The retina and internal ocular structures were examined using dilated ophthalmoscopy. For out-patients evaluated within the private practice, a slit-lamp evaluation of the corneal tear layer was utilized in the diagnosis of dry eye syndrome. For in-patients who could not be assessed with a slit-lamp, a portable blue filter with fluorescence staining was utilized for the diagnosis of dry eye syndrome. Photophobia was diagnosed by assessing a patient’s sensitivity to direct light stimulation during pupil examination.

Vestibular dysfunction was assessed using the patient’s symptoms, including dizziness / vertigo and other vestibular tests including electronystagmograph (ENG) and caloric testing. The diagnosis of a vestibular dysfunction was attained from the physical therapist’s or otologist’s evaluation. In summary, the following were examined within the TBI population in order to diagnose visual or vestibular dysfunctions: visual acuity, accommodation, binocular vision, oculomotor function, visual fields, ocular health, and vestibular function.

Statistical Analyses

Visual examinations from 557 TBI patients were available for analysis. Within this manuscript, CI refers to convergence insufficiency and not the common statistical acronym of confidence interval. The chi-squared test was used to test the null hypothesis for the attributes that were mutually exclusive between the CI and non-CI groups. For example, the brain injury of patients was evoked via one mechanism of injury, not multiple types. Hence, this attribute was mutually exclusive and the chi-squared test is the appropriate test to assess statistically significant differences. The chi-squared test assumes chi-squared distribution. The Z-test was used to test the null hypothesis for patient attributes that were not mutually exclusive such as the diagnoses of visual dysfunctions where multiple types of visual dysfunctions per patient were commonly reported. The Z-test assumes a Gaussian or normal distribution.

The use of the Z-test was first evaluated to determine the validity of the test. For a study of normal representation of the Z-test, one should consider the mean plus / minus three standard deviations of count to lie between zero and the sample size. The equation (np is the expected number of counts for an attribute; p is the probability of a patient with the attribute; and n is the sample size) is applied to obtain the number of samples for sufficient power. Since 557 visual examinations are available for analysis, the equation can be rewritten as:

| (1) |

Solving for p, determines the smallest prevalence rate one can accurately report for the given sample size studied. The smaller the prevalence rate, the larger the sample size needed to validate the test. With a sample size of n = 557, equation (1) shows that the Z-test has sufficient power to assess prevalence rates as small as 1.59% and as large as 98.41%. The use of the Chi-square tests is also justified by a large sample size.

The TBI data were segregated into CI and non-CI subgroups. Since the mechanism of injury and acuity levels were mutually exclusive, differences between the CI and non-CI groups were assessed with the chi-squared test. Differences between the type of visual dysfunction within the CI and non-CI subgroups were assessed with a Z-test because these types of visual dysfunctions were not mutually exclusive. The TBI data were also divided into in-patient and out-patient subgroups and differences between the types of visual dysfunction were also assessed with the Z-test. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant for the chi-squared tests. Since, the data for the Z-tests were analyzed with multiple tests a Bonferroni correction for the multiplicity of tests was conducted to avoid Type I error. There were 16 tests; hence, the p-values for statistical significance of the Z-tests were reduced to p<0.05 divided by the number of tests, which is 16. Hence, when corrected for multiplicity of tests, the significance level became p<0.003. The statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software (SAS 9.2, SAS Institute) by a statistician, one of the co-authors (S.K.D.).

RESULTS

The following results will be presented: facility where patients were evaluated, mechanism of injury as a function of age, visual acuity as a function of the mechanism of injury, and the prevalence of visual dysfunction per mechanism of injury. The mechanism of injury, visual acuity, visual dysfunctions, and visual field loss were analyzed for the whole TBI population as well as the CI and non-CI subgroups. Accommodative dysfunction was analyzed for the non-presbyopic subgroup. The prevalence of visual dysfunctions was also compared between the in-patient and out-patient subgroups.

Facility of Patient Evaluation

The facilities where the patients were evaluated are reported in Table 1. Patients were categorized by the type of care administered. Within the TBI sample, 48.5% were in-patients while 51.5% were out-patients. The mean age of the patients examined was 40.3 ± 17.4 with a range from 5 to 89 years of age. More than half, 56% (N=314/557) of the TBI patients, were less than forty years of age.

Table 1.

Institution, location, the number of TBI patients from the different facilities within the state of New Jersey, USA.

| Facility | Number of Patients | % of Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Total In-patient | 270 | 48.5 |

| KIR, West Orange | 156 | 28.0 |

| KIR, Chester | 50 | 9.0 |

| KIR, Saddle Brook | 15 | 2.7 |

| JFKMC, Edison | 44 | 7.9 |

| RWJUH, New Brunswick | 5 | 0.9 |

|

| ||

| Total Out-patient | 287 | 51.5 |

| Private Practice, Westfield | 287 | 51.5 |

|

| ||

| Total | 557 | 100.0 |

KIR = Kessler Institute of Rehabilitation;

RWJUH = Robertwood Johnson University Hospital;

JFKMC = John F Kennedy Medical Center

Mechanism of Injury as a Function of Age

All the patients within this current study have experienced a TBI, documented within their medical records by a neurologist. There are several mechanisms of injury where the most common included motor vehicle accidents (70.9%), falls (14.7%), a strike or blow to the head from, or against, an object (9.2%), or sports injury (2.5%). A strike or blow to the head is consistent with the Center for Disease Control categories for the mechanisms of injuries. A typical example would be someone having an object, such as a tool, strike the patient’s head during an occupational activity. The other mechanisms of injuries include gunshot, assaults or a very small percentage of unspecified TBI (2.7%). The mechanism of injury for the CI (N=130/557) and non-CI (N=427/557) subgroups within the TBI sample is reported in Table 2. The CI subgroup is not significantly different than the non-CI subgroup based upon the mechanism of injury (DF = 4; χ2 = 4.4; p=0.36).

Table 2.

Mechanism of injury for the whole TBI sample as well as the CI and non-CI subgroup within the TBI sample. Data are reported in terms of the percentage of the sample, mean age, standard deviation and age range in years.

| Mechanism of Injury | All TBI % (N) | Age (yr) | Standard Deviation of Age (yr) | Age Range (yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire TBI Sample (N=557 Total Cases) | ||||

| Motor Vehicle Accident (MVA) | 70.9 (395/557) | 37.2 | 16.2 | 5 to 82 |

| Fall | 14.7 (82/557) | 54.7 | 19.8 | 16 to 89 |

| Strike or blow to the head from or against an object (S/B) | 9.2 (51/557) | 38.5 | 14.9 | 9 to 82 |

| Sports Injury (SI) | 2.5 (14/557) | 39.4 | 15.5 | 14 to 72 |

| Other | 2.7 (15/557) | 49.8 | 14.9 | 26 to 71 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 100.0 (557/557) | 40.3 | 17.4 | 5 to 89 |

|

| ||||

| CI subgroup within TBI (N=130 Total Cases) | ||||

| Motor Vehicle Accident (MVA) | 69.2 (90/130) | 39.7 | 16.6 | 12 to 79 |

| Fall | 13.1 (17/130) | 53.9 | 17.7 | 23 to 82 |

| Strike or blow to the head from or against an object | 11.5 (15/130) | 44.3 | 11.2 | 21 to 58 |

| Sports Injury (SI) | 1.5 (2/130) | 35.5 | 6.7 | 35 to 40 |

| Other | 4.6 (6/130) | 52.0 | 18.9 | 26 to 71 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 100.0 (130/130) | 46.0 | 16.1 | 12 to 82 |

|

| ||||

| Non-CI subgroup within TBI (N=427 Total Cases) | ||||

| Motor Vehicle Accident (MVA) | 71.4 (305/427) | 36.4 | 16.2 | 5 to 82 |

| Fall | 15.2 (65/427) | 55.1 | 20.5 | 16 to 89 |

| Strike or blow to the head from or against an object | 8.4 (36/427) | 37.6 | 16.2 | 9 to 82 |

| Sports Injury (SI) | 2.8 (12/427) | 42.4 | 18.1 | 14 to 72 |

| Other | 2.1 (9/427) | 45.6 | 13.7 | 27 to 67 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 100.0 (427/427) | 43.4 | 16.9 | 5 to 89 |

Visual Acuity as a Function of the Mechanism of Injury

The majority of TBI patients (84.9%) has 20/60 acuity or better. Total blindness or no light perception in either eye is observed in 0.8% (N=4/520) of the TBI sample. The following types of refractive errors are observed in the TBI population: myopia (17.8%), simple myopic astigmatism (5.7%), compound myopic astigmatism (22.6%), hyperopia (19.4%), simple hyperopic astigmatism (0.7%), compound hyperopic astigmatism (24.2%), and mixed astigmatism (2.5%). The remaining 7.2% are categorized as having emmetropia. Table 3 summarizes the visual acuity of patients from the entire TBI sample, the CI subgroup and the non-CI subgroup within the TBI sample. Visual acuities are not available for 37 patients within the TBI sample (one patient in the CI subgroup and 36 patients in the non-CI subgroup) due to the patients’ inabilities to respond informatively. Visual acuity loss of 20/70 or worse is observed in 9.0% (N=47/520) of the TBI sample, in 10.1% (N=13/129) of the CI subgroup, and in 8.7% (N=34/391) of the non-CI subgroup. The chi-squared test reports no significant differences in visual acuity comparing the CI to the non-CI subgroups (DF=3; χ2=4.5; p=0.21, but 38% of the cells have expected counts less than 5). Hence, data were categorized without the stratification of the mechanism of injury and the following types of visual acuity were re-examined: 20/60 or better, 20/70 to 20/100, and no light perception or below 20/100. Chi-squared analysis still revealed no significant differences in visual acuity between CI to the non-CI subgroups (DF=2; χ2=3.6; p=0.17) where cell counts were all greater than 5 observations.

Table 3.

Visual acuity in terms of mechanism of injury for the entire TBI sample as well as the CI and non-CI subgroup within the TBI sample. Data are reported in terms of the percentage of the sample with the number of patients.

| Visual Acuity/ Impairment | MVA | Fall | S/B | SI | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI % (N of 557 Total Cases) | ||||||

| 20/60 or better | 60.9 (339) | 12.4 (69) | 7.0 (39) | 2.0 (11) | 2.7 (15) | 84.9 (473) |

| 20/70-20/100 | 5.2 (12) | 0.4 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.2 (1) | 2.9 (16) |

| Less than 20/100 | 2.9 (16) | 0.7 (4) | 1.1 (6) | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 4.8 (27) |

| No Light Perception | 0.2 (1) | 0.2 (1) | 0.4 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.7 (4) |

| Unavailable Due to Patient Inability to Respond | 4.9 (27) | 1.1 (6) | 0.4 (2) | 0.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 6.6 (37) |

|

| ||||||

| CI subgroup within TBI % (N of 130 Total Cases) | ||||||

| 20/60 or better | 61.5 (80) | 13.1 (17) | 9.2 (12) | 1.5 (2) | 3.8 (5) | 89.2 (116) |

| 20/70-20/100 | 3.8 (5) | 0.0 (0) | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.8 (1) | 5.4 (7) |

| Less than 20/100 | 3.1 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 1.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 4.6 (6) |

| No Light Perception | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Unavailable Due to Patient Inability to Respond | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.8 (1) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-CI subgroup within TBI % (N of 427 Total Cases) | ||||||

| 20/60 or better | 60.7 (259) | 12.2 (52) | 6.3 (27) | 2.1 (9) | 2.3 (10) | 83.6 (357) |

| 20/70-20/100 | 1.6 (7) | 0.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 2.1 (9) |

| Less than 20/100 | 2.8 (12) | 0.9 (4) | 0.9 (4) | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 4.9 (21) |

| No Light Perception | 0.2 (1) | 0.2 (1) | 0.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.9 (4) |

| Unavailable Due to Patient Inability to Respond | 6.1 (26) | 1.4 (6) | 0.5 (2) | 0.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 8.4 (36) |

MVA = Motor Vehicle Accident;

S/B = Strike or blow to the head from or against an object;

SI = Sports Injury.

Prevalence of Visual Dysfunction for the Entire TBI Population, CI and non-CI Subgroups

Table 4 summarizes the visual dysfunctions within the whole TBI sample per mechanism of injury. CI was one of the most common visual dysfunctions observed within TBI (23.3%, N=130/557). The CI subgroup was analyzed to determine the prevalence of simultaneous visual dysfunctions within this group. Approximately 9.2% (N=51/557) of this entire sample TBI population or 39.2% (N=51/130) of the CI subgroup within this TBI sample were diagnosed with CI without the following simultaneous diagnoses: saccade or pursuit dysfunction; 3rd, 4th, or 6th nerve palsy; visual field deficit; visual spatial inattention / neglect; nystagmus; or vestibular dysfunction, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Visual dysfunctions within the TBI sample as well as the CI and non-CI subgroup within TBI sample. Data are reported in terms of the percentage of the sample with the number of patients.

| Visual Dysfunctions | MVA | Fall | S/B | SI | Other | Total (N=557) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBI% (N of 557 Total Cases) | ||||||

| Convergence Insufficiency | 16.2 (90) | 3.1 (17) | 2.7 (15) | 0.4 (2) | 1.1 (6) | 23.3 (130) |

| Saccadic / Pursuit Dysfunction | 5.0 (28) | 1.6 (9) | 0.7 (4) | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 7.5 (42) |

| Nystagmus | 3.1 (17) | 0.5 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 0.2 (1) | 0.2 (1) | 3.9 (22) |

| 3rd Nerve Palsy | 4.3 (24) | 0.9 (5) | 0.2 (1) | 0.4 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 5.9 (33) |

| 4th Nerve Palsy | 7.7 (43) | 1.4 (8) | 0.4 (2) | 0.4 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 10.1 (56) |

| 6th Nerve Palsy | 2.7 (15) | 1.3 (7) | 0.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 4.3 (24) |

| Photophobia | 8.1 (45) | 0.7 (4) | 0.7 (4) | 0.4 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 10.1 (56) |

| Dry Eye Syndrome | 5.9 (33) | 2.3 (13) | 1.8 (10) | 0.0 (0) | 0.4 (2) | 10.4 (58) |

| Vestibular Dysfunction | 11.6 (65) | 0.7 (4) | 1.1 (6) | 0.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 13.8 (77) |

|

| ||||||

| CI subgroup within TBI % (N of 130 Total Cases) | ||||||

| Saccadic / Pursuit Dysfunction | 3.8 (5) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 3.8 (5) |

| Nystagmus | 4.6 (6) | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 6.2 (8) |

| 3rd Nerve Palsy | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.8 (1) |

| 4th Nerve Palsy | 3.8 (5) | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 4.6 (6) |

| 6th Nerve Palsy | 0.8 (1) | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.5 (2) |

| Photophobia | 14.6 (19) | 0.8 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 15.4 (20) |

| Dry Eye Syndrome | 8.5 (11) | 1.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 10 (13) |

| Vestibular Dysfunction | 16.2 (21) | 0.8 (1) | 1.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 18.5 (24) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-CI subgroup within TBI % (N of 427 Total Cases) | ||||||

| Saccadic / Pursuit Dysfunction | 5.4 (23) | 2.1 (9) | 0.9 (4) | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 8.7 (37) |

| Nystagmus | 2.6(11) | 0.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.2 (1) | 3.3 (14) |

| 3rd Nerve Palsy | 5.4 (23) | 1.2 (5) | 0.2 (1) | 0.5 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 7.5 (32) |

| 4th Nerve Palsy | 9.0 (38) | 1.6 (7) | 0.5 (2) | 0.5 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 11.7 (50) |

| 6th Nerve Palsy | 3.3 (14) | 1.4 (6) | 0.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 5.2 (22) |

| Photophobia | 6.1 (26) | 0.7 (3) | 0.9 (4) | 0.5 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 8.4 (36) |

| Dry Eye Syndrome | 5.2 (22) | 2.6 (11) | 2.3 (10) | 0.0 (0) | 0.5 (2) | 10.5 (45) |

| Vestibular Dysfunction | 10.3 (44) | 0.7 (3) | 0.9 (4) | 0.5 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 12.4 (53) |

MVA = Motor Vehicle Accident; S/B =strike or blow to the head from or against an object; SI = Sports Injury

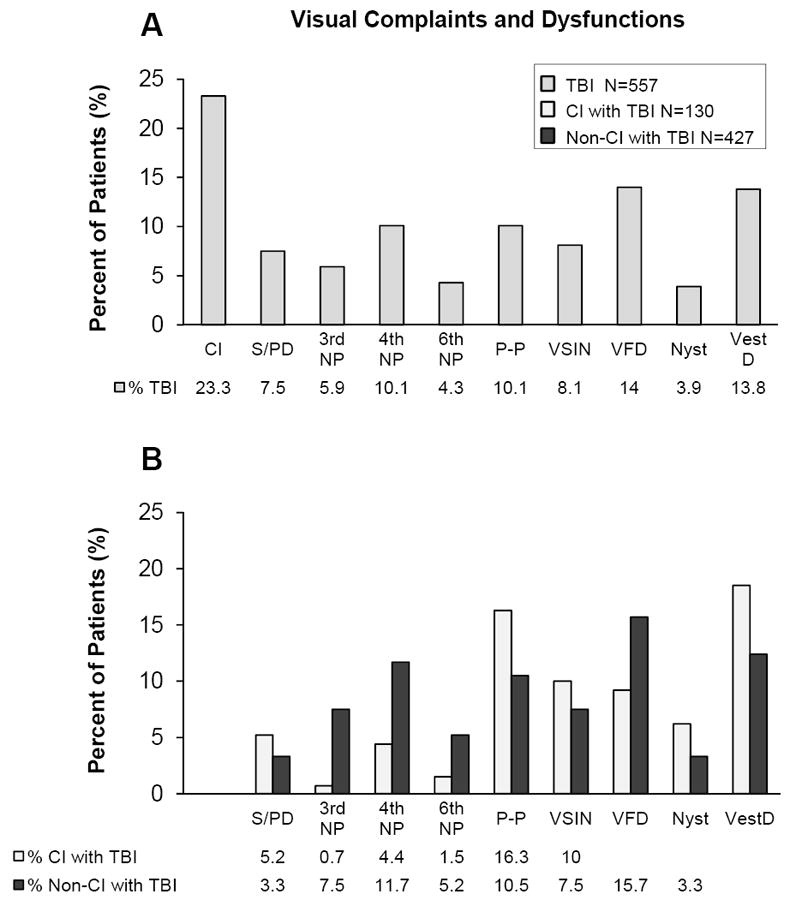

Figure 1.

Visual dysfunctions within the TBI sample (plot A, medium gray) and the CI subgroup (plot B, light gray) and non-CI subgroup (plot B, dark gray) within the TBI sample. Visual dysfunctions are abbreviated as follows: convergence insufficiency (CI), saccadic and pursuit dysfunction (S/PD), 3rd nerve palsy (3rd NP), 4th nerve palsy (4th NP), 6th nerve palsy (6th NP), photophobia (P-P), visual spatial inattention / neglect (VSIN), visual field deficit (VFD), nystagmus (Nyst) and vestibular dysfunction (VestD).

Figure 1 summarizes the prevalence of visual dysfunctions commonly observed within this TBI patient sample (plot A) and within the CI and non-CI subgroups of the TBI sample (plot B). The CI and non-CI subgroups within the TBI sample in terms of the type of visual dysfunction per mechanism of injury are summarized in Table 4. Since the chi-squared test did not show significant differences in the mechanism of injury between the CI and non-CI subgroups, data were not stratified per the mechanism of injury. The CI and non-CI subgroups were compared using Z-tests for each type of visual dysfunction. A greater prevalence of 3rd nerve palsy (|z|=2.84; p=0.005), 4th nerve palsy (|z|=2.36; p=0.02) and 6th nerve palsy (|z|=1.78; p=0.08) was observed within the non-CI compared to the CI group; however, these differences were not significant after a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison (p<0.003) to avoid Type I family errors. Conversely, a greater prevalence of photophobia (|z|=2.31; p=0.02), saccadic and pursuit dysfunction (|z|=1.82; p=0.07), nystagmus (|z|=1.47; p=0.14), and vestibular dysfunction (|z|=1.75; p=0.08) were observed in the CI group compared to the non-CI group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Visual field data were summarized in Table 5. Field deficits were delineated as right or left homonymous hemianopsia or quadrantopsia. Visual field deficits were observed in 14.2% (N=79/557) and visual spatial inattention / neglect was observed in 8.1% (N=45/557) of the TBI patients. Significant differences in visual field deficits (|z|=1.85; p=0.06) and unilateral visual-spatial inattention / neglect (|z|=0.92; p=0.36) were not observed between the CI and non-CI subgroups.

Table 5.

Visual field deficits and unilateral visual-spatial inattention / neglect for the TBI sample, the CI subgroup and Non-CI subgroup within the TBI sample. Data are reported in terms of the percentage of the sample with the number of patients.

| Visual Field Deficits | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| TBI % (N of 557) | CI Subgroup within TBI % (N of 130) | Non-CI Subgroup within TBI % (N of 427) | |

| Right Homonymous Hemianopsia | 3.8 (21) | 0.8 (1) | 4.7 (20) |

| Left Homonymous Hemianopsia | 4.3 (24) | 3.9 (5) | 4.4 (19) |

| Quadrantopsia | 6.1 (34) | 4.6 (6) | 6.6 (28) |

| Total | 14.2 (79) | 9.2 (12) | 15.7 (67) |

|

| |||

| Unilateral Visual-Spatial Inattention / Neglect | |||

| TBI % (N of 557) | CI Subgroup within TBI % (N of 130) | Non-CI Subgroup within TBI % (N of 427) | |

| Right Unilateral Visual-Spatial Inattention/Neglect | 2.2 (12) | 3.1 (4) | 1.9 (8) |

| Left Unilateral Visual-Spatial Inattention/Neglect | 5.9 (33) | 6.9 (9) | 5.6 (24) |

| Total | 8.1 (45) | 10.0 (13) | 7.5 (32) |

The prevalence of accommodative dysfunction was evaluated for the non-presbyopic TBI sample where 24.2% (N=76/314) of the TBI sample, 31.1% (N=19/61) of the CI subgroup, and 22.5% (57/253) of the non-CI subgroup were diagnosed with accommodative dysfunction. There were no significant differences observed in the prevalence of accommodative dysfunction between the CI and non-CI non-presbyopic samples (|z|=1.41; p=0.16).

Prevalence of Vision Dysfunction within the In-Patient compared to Out-Patient Subgroups

TBI patients tested while hospitalized (in-patient; N=270/557) were compared to the TBI patients tested in the out-patient setting (out-patient; N=287/557), summarized within Table 6. The prevalence of CI, saccadic / pursuit dysfunction, nystagmus, 3rd and 4th nerve palsy, dry eye syndrome, and accommodation dysfunction were not significantly different between the in-patient versus out-patient subgroups, corrected for multiple comparisons (p>0.003). A significantly greater prevalence of 6th nerve palsy (|z|=3.08; p=0.002), unilateral visual-spatial inattention / neglect (|z|=4.41; p<0.0001), and visual field deficit (|z|=3.57; p<0.001) were observed within the in-patient subgroup compared to the out-patient subgroup. The prevalence of photophobia was greater within the out-patient compared to in-patient subgroup but was not considered significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (|z|=2.06; p=0.04).

Table 6.

Visual dysfunctions within in-patient (left column) and out-patient (right column) subgroups. Data are reported in terms of the percentage of the sample with the number of patients.

| Visual Dysfunctions | ||

|---|---|---|

| In-Patient % (N=270) | Out-Patient % (N=287) | |

| Convergence Insufficiency | 23.3 (63) | 23.3 (67) |

| Saccadic / Pursuit Dysfunction | 8.5 (23) | 6.6 (19) |

| Nystagmus | 3.7 (10) | 4.2 (12) |

| 3rd Nerve Palsy | 7.0 (19) | 4.9 (14) |

| 4th Nerve Palsy | 10.4 (28) | 9.8 (28) |

| 6th Nerve Palsy | 7.0 (19) | 1.7 (5) |

| Dry Eye Syndrome | 11.9 (32) | 9.1 (26) |

| Photophobia | 7.0 (19) | 12.2 (35) |

| Unilateral Visual-Spatial Inattention/Neglect | 13.3 (36) | 3.1 (9) |

| Visual Field Deficit | 19.6 (53) | 9.1 (26) |

|

| ||

| Accommodation Dysfunction in Non-Presbyopic Sample | ||

| In-Patient % (N=136) | Out-Patient % (N=178) | |

| Accommodation Dysfunction | 27.2 (37) | 21.9 (39) |

DISCUSSION

Primary Finding

The primary finding of the study was that 9.2% of the CI patients within this TBI sample were observed without the following simultaneous diagnoses: saccade or pursuit dysfunction; 3rd, 4th, or 6th nerve palsy; visual field deficit; visual spatial inattention / neglect; nystagmus; or vestibular dysfunction within a visually symptomatic TBI population. The analyzes presented investigate important visual examination attributes to consider when designing future randomized clinical trials of CI to estimate recruitment efforts and conduct power analyses while reducing the number of potentially confounding variables. One other potentially confounding variable within CI is attention disorders. Granet and colleagues report a high co-morbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with CI.71 Difficulty with attention is a common cognitive complaint in TBI patients.35-39 Attention was not evaluated within this dataset and is a study limitation.

Comparison of the Current Findings to other Literature

The present study will be compared to prior TBI literature in terms of: the mechanism of injury, visual dysfunctions specifically of in-patient compared to out-patient subgroups and the prevalence of the visual dysfunctions within non-stratified TBI populations. The specific visual dysfunctions that were compared to previous investigations of civilian and veteran TBI populations were: CI, accommodative dysfunction, saccades or smooth pursuit dysfunction, cranial nerve palsies, visual acuity, and visual field loss.

Mechanism of Injury

These data demonstrate that motor vehicle accidents (MVA) were the primary mechanism of injury in the present study, followed by falls. These data are in agreement with the latest Center for Disease Control report which states that MVA, falls and assaults are the most common causes of TBI within the civilian population.1

In-Patient Compared to Out-Patient Subgroups

Patients can be categorized into numerous severity groups and stratified by TBI-related, functional, and other recovery-related variables. Examples include the type of care administered, burden of disability, disease factors, length of time since injury, severity of injury, or economic means to attain proper treatment where these factors may affect the incidence and complexity of visual disorders after TBI. In future, prospective studies, these categories should be studied in an unselected TBI population from numerous clinical sites and observed by several clinicians to evaluate their relationship with TBI-related CI. For the current study, patients were categorized by the offsetting in which TBI care was being administered (in-patient compared to out-patient) since severity of injury was not available.

Although the severity of injury was not available within the examination files, a Functional Independence Measurement (FIM) was assessed on all TBI patients from the Kessler Institute (82% of the TBI in-patient population). The FIM is an 18-item, 7-level scale to evaluate the severity of patient disability and medical rehabilitation functional outcome.72 A literature review using a meta-analysis reports that when assessing the average interclass correlation coefficient (ICC), the total FIM has a median interrater reliability of 0.95 and concludes the FIM is reliable when used by trained in-patient medical rehabilitation clinicians.73 A FIM was assessed on Kessler patients before admittance as well as upon discharge from in-patient care. The visual function assessment for in-patients was measured two to three weeks post acute care within the in-patient rehabilitation facilities, which is consistent with the TBI Model Systems practice.74,75 At the Kessler Institute, during the last two quarters of 2011, the average total FIM upon TBI rehabilitation admission was 43.3 and the average total FIM upon TBI rehabilitation discharge was 70.6. These recent results are typical for the TBI population routinely observed at the Kessler Institute. The FIM scores from the Kessler TBI population were lower compared to another study76 and to the reported total FIM from all sixteen sites within the TBI Model Systems Database (52 for rehabilitation admission, N=9861; 92 for rehabilitation discharge, N=9781).74 These data suggest that TBI in-patients from Kessler on average may be more severely affected, with pathology in the moderate-severe rather than mild TBI range.

Lower average FIM scores are observed within the in-patient population, compared to the average FIM upon discharge, or out-patient population. There was a significantly greater prevalence of 6th nerve palsy, unilateral visual-spatial inattention / neglect, and visual field deficits within the in-patient compared to out-patient population of this present study. Such significant decreases in visual dysfunction in the out-patient population may be related to patients demonstrating some natural resolution of visual problems over time as the brain injury is healing.

Convergence Insufficiency (CI)

These data report that 23.3% (N=130/557) of the TBI sample was diagnosed with CI. These results are less than the frequency reported by Ciuffreda et al. (42.5%; N=160), Cohen et al. (42%; N=72), and Brahm et al. (46.4%; N=183).9, 17, 44 In addition, convergence dysfunction was reported in 46% (N=62)20 and 30.4% (N=46)19, while convergence disorder was present in 28% (N=36) of a military population in a VA Polytrauma Network Site.77 The prevalence rate of this study may be lower due to differences in the diagnosis of CI between studies. For example, the prevalence of CI from the general population without a history of head trauma has a reported variance of 3.5% to 8%. 78-81 A portion of the variance is presumed to be attributed to the definition used for the diagnosis, where some clinicians use only NPC and others use NPC, phoria, fusional range, and / or symptoms. The recent randomized clinical trial called the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) defines CI as an NPC of 6 cm or greater, a convergence insufficiency symptom survey (CISS) score greater than 16 for children or 21 for adults, and an exophoria at near with at least 4 prism diopters greater than the distance phoria. 50, 51, 82, 83 Within the TBI literature, Brahm et al. defined CI as an NPC greater than 7 cm.17 The definition used in the current analysis to diagnose CI included NPC and a failure to meet Sheard’s criterion, which is more stringent than prior investigations and may potentially lead to a lower prevalence rate. In addition, Cohen et al. studied a sample of severe TBI patients44 which implies CI may be more commonly observed in a TBI population with more severe injuries.

Accommodative Dysfunction

Within these present data, accommodative dysfunction was observed in 24.2% (N=76/314) of the non-presbyopic TBI population (patients who were 40 years of age or younger) and 31.1% (N=19/61) of the non-presbyopic CI subgroup. The results of the present study are less than the prevalence of accommodation dysfunction reported by Ciuffreda et al. (41.1% N=51)9 and Stelmack et al. (47% N=36)77 and similar to those reported by Goodrich et al. (21.7% N= 46)19 and Lew et al. (21% N=62).20 Future prospective studies should striate accommodative dysfunctions into accommodative insufficiency, excess and infacility. This information was not available within the current dataset and is a limitation of the study.

Saccades and/or Pursuit Dysfunction

Within this dataset, the frequency of saccade and / or pursuit dysfunction within the TBI sample was 7.5%. The results of this dataset were similar to those reported by Stelmack et al. who studied veterans with TBI (6.0%)77 but greater than those reported by Goodrich et al. who studied a combat injured TBI patient population (0.9%).19 Similar to this current study, both Brahm et al. and Goodrich et al. subjectively assessed saccades for accuracy and speed and assessed pursuit movements for accuracy and smoothness.17, 19

Cranial Nerve Palsies

Ciuffreda et al. report a similar frequency of third cranial nerve palsy (6.9%) compared to this analysis (5.9%).10 Third cranial nerve palsy is commonly reported after motor vehicle accidents.84-87 In addition, the literature reports that third, fourth and sixth cranial nerve palsies are associated with severe head injuries.88

Visual Acuity

Visual acuity was normal or near to normal in 84.9% of this TBI patient sample, and were not significantly different between the CI and non-CI subgroups. Other studies report that visual acuity loss was more common in patients who sustained greater level of injury resulting in moderate or severe TBI.17 Given the prevalence of other vision dysfunctions, these data imply that visual acuity alone, one of the basic elements of vision assessment, is not an adequate representation of visual function for the TBI population.

Visual Fields

This study reports 20.1% (N=112/557) of the TBI patient sample had visual field defects classified as visual spatial inattention / deficit or field loss, or both. The in-patient visual examinations revealed that 29.6% (N=80/270) of the patients had visual field defects. The results are similar to the Brahm et al. study which reports 32.2% of in-patients (N=19/59), and to the Suchoff et al. study, which reports 38.8% of TBI patients, (N=62/160) had field loss. 15, 17 Suchoff et al. did not stratify their TBI sample in terms of type of administered care.15 When analyzing the out-patient data, 11.1% (N=32/287) had visual spatial inattention / deficit or field loss, or both, which is comparable to Brahm et al. who report a prevalence of 3.2% (N=4/124) within their out-patient population.17 Within the civilian population analyzed, significantly greater prevalence of visual field defects were observed in the in-patient, compared to the out-patient, populations, which may be related to the severity of TBI-related deficits during the acute, in-hospital period of TBI recovery. A similar finding is reported by Brahm et al. when studying a military population.17 These data support that visual field deficits are common within the TBI population. Hence, visual field assessment is recommended to be evaluated in all TBI patients, because visual field defects are known to have adverse effects on the functions of activities of daily living and mobility. 89-91

Study Limitations

The Glascow Coma Scale (GCS), type and severity of TBI, as well as the time since injury, were not available for this present investigation and are limitations of the current study. A prospective analysis of vision dysfunction from a group of clinicians of the general, unselected TBI population of patients, not just those patients referred for a visual examination based upon a visual screening test, is suggested for future studies. It is suggested that the visual dysfunction, visual symptoms, and location of injury be analyzed as a function of TBI severity and time since the insult. Such an analysis may reveal which measured visual parameters and symptoms correlate to the severity and type of injury, as well as how visual indexes may change as a function of the time since the injury.

Since the TBI population analyzed was visually symptomatic, the percentages reported may be greater than those occurring in an unselected group of TBI patients. However, visual-based symptoms post-TBI are common. A recent survey-based analysis of 12,521 unselected veterans returning from Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom reports 44.5% had visual impairment based upon self-reporting symptoms.92 This large study analysis is a subjective survey and not a study of visual examinations performed by eye care professionals but it supports that vision complaints are common post TBI from combat related injuries.

Despite these limitations, the data analyzed within this present study support that vision and vestibular dysfunctions are common within the TBI population. Hence, a thorough visual and vestibular examination is suggested for TBI patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Approximately 9% of this TBI sample population had CI without the following simultaneous diagnoses: saccade or pursuit dysfunction; 3rd, 4th, or 6th nerve palsy; visual field deficit; visual spatial inattention / neglect; nystagmus or vestibular dysfunction. This information is needed to conduct an accurate power analysis for randomized clinical trials studying those with CI and TBI. A thorough visual functional examination for TBI patients is recommended since visual dysfunctions post TBI are common. In addition, TBI can impair the ability to report symptoms such as visual disturbance; hence vision dysfunction may be present while the patient is unaware or unable to report visual symptoms. Since many of the patients in this study may have been evaluated because they reported symptoms, it is also important to examine how frequently CI and other visual dysfunctions occur in an unselected prospective TBI patient group, especially in those who do not report visual problems. Future studies should also include quantitative measurements such as eye movement analyses coupled with functional MRI and diffusion tensor imaging to expose the underlying neural damage evoked via TBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Semmlow, PhD and Norbert Elliot, PhD for comments on the manuscript and writing style and Mooyeon Oh-Park, MD for summarizing the Kessler Institute TBI FIM statistics.

This research was supported in part by NSF CAREER BES-044713 to TLA, NIH R01NS055808 to AMB, and 5R01NS049176 to BBB.

References

- 1.Coronado VG, Xu L, Basavaraju SV, McGuire LC, Wald MM, Faul MD, Guzman BR, Hemphill JD. Surveillance for traumatic brain injury-related deaths--United States, 1997-2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kraus JF, Nourjah P. The epidemiology of mild, uncomplicated brain injury. J Trauma. 1988;28:1637–43. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kushner D. Mild traumatic brain injury: toward understanding manifestations and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1617–24. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.15.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meythaler JM, Peduzzi JD, Eleftheriou E, Novack TA. Current concepts: diffuse axonal injury-associated traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1461–71. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.25137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraus JF, McArthur DL, Silberman TA. Epidemiology of mild brain injury. Semin Neurol. 1994;14:1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1041052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Numminen HJ. The incidence of traumatic brain injury in an adult population--how to classify mild cases? Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:460–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang TT, Ciuffreda KJ, Kapoor N. Critical flicker frequency and related symptoms in mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2007;21:1055–62. doi: 10.1080/02699050701591437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciuffreda KJ, Han Y, Kapoor N, Ficarra AP. Oculomotor rehabilitation for reading in acquired brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 2006;21:9–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ciuffreda KJ, Kapoor N, Rutner D, Suchoff IB, Han ME, Craig S. Occurrence of oculomotor dysfunctions in acquired brain injury: a retrospective analysis. Optometry. 2007;78:155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciuffreda KJ, Rutner D, Kapoor N, Suchoff IB, Craig S, Han ME. Vision therapy for oculomotor dysfunctions in acquired brain injury: a retrospective analysis. Optometry. 2008;79:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ. Vision disturbances following traumatic brain Injury. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2002;4:271–80. doi: 10.1007/s11940-002-0027-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ, Han Y. Oculomotor rehabilitation in acquired brain injury: a case series. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:1667–78. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutner D, Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ, Craig S, Han ME, Suchoff IB. Occurrence of ocular disease in traumatic brain injury in a selected sample: a retrospective analysis. Brain Inj. 2006;20:1079–86. doi: 10.1080/02699050600909904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrupp LE, Ciuffreda KJ, Kapoor N. Foveal versus eccentric retinal critical flicker frequency in mild traumatic brain injury. Optometry. 2009;80:642–50. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2009.04.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suchoff IB, Kapoor N, Ciuffreda KJ, Rutner D, Han E, Craig S. The frequency of occurrence, types, and characteristics of visual field defects in acquired brain injury: a retrospective analysis. Optometry. 2008;79:259–65. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.al-Qurainy IA. Convergence insufficiency and failure of accommodation following midfacial trauma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;33:71–5. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(95)90203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brahm KD, Wilgenburg HM, Kirby J, Ingalla S, Chang CY, Goodrich GL. Visual impairment and dysfunction in combat-injured servicemembers with traumatic brain injury. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:817–25. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181adff2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockerham GC, Goodrich GL, Weichel ED, Orcutt JC, Rizzo JF, Bower KS, Schuchard RA. Eye and visual function in traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:811–8. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2008.08.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodrich GL, Kirby J, Cockerham G, Ingalla SP, Lew HL. Visual function in patients of a polytrauma rehabilitation center: A descriptive study. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:929–36. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.01.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lew HL, Poole JH, Vanderploeg RD, Goodrich GL, Dekelboum S, Guillory SB, Sigford B, Cifu DX. Program development and defining characteristics of returning military in a VA Polytrauma Network Site. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:1027–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenner LA, Ivins BJ, Schwab K, Warden D, Nelson LA, Jaffee M, Terrio H. Traumatic brain injury, posttraumatic stress disorder, and postconcussive symptom reporting among troops returning from iraq. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2010;25:307–12. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181cada03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivins BJ. Hospitalization associated with traumatic brain injury in the active duty US Army: 2000-2006. NeuroRehabilitation. 2010;26:199–212. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2010-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thurman DJ. The epidemiology and economics of head trauma. In: Miller LP, Hayes RL, editors. Head Trauma: Basic, Preclinical, and Clinical Directions. New York: Liss; 2001. pp. 327–48. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:453–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West TD, Marsh JO. Rebuilding the Trust: Independent Review Group Report on Rehabilitative Care and Administrative Processes at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and National Naval Medical Center. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanielian T, Jaycox LH RAND Corporation. [August 16, 2012];Stop Loss: A Nation Weighs the Tangible Consequences of Invisible Combat Wounds. 2008 Summer; Available at: http://www.rand.org/publications/randreview/issues/summer2008/wounds1.html.

- 27.Sayer NA, Rettmann NA, Carlson KF, Bernardy N, Sigford BJ, Hamblen JL, Friedman MJ. Veterans with history of mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder: challenges from provider perspective. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:703–16. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2009.01.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams JH, Doyle D, Ford I, Gennarelli TA, Graham DI, McLellan DR. Diffuse axonal injury in head injury: definition, diagnosis and grading. Histopathology. 1989;15:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams JH, Graham DI, Murray LS, Scott G. Diffuse axonal injury due to nonmissile head injury in humans: an analysis of 45 cases. Ann Neurol. 1982;12:557–63. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iverson GL. Outcome from mild traumatic brain injury. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005;18:301–17. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000165601.29047.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaetz M. The neurophysiology of brain injury. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:4–18. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:4–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greve MW, Zink BJ. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:97–104. doi: 10.1002/msj.20104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kochanek PM, Clark RSB, Jenkins LW. TBI: pathobiolgy. In: Zasler ND, Katz DI, Zafonte RD, editors. Brain Injury Medicine: Principles and Practice. New York: Demos; 2007. pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishnan M, Donders J. Embedded assessment of validity using the continuous visual memory test in patients with traumatic brain injury. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;26:176–83. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sosnoff JJ, Broglio SP, Shin S, Ferrara MS. Previous mild traumatic brain injury and postural-control dynamics. J Athl Train. 2011;46:85–91. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prigatano GP, Gale SD. The current status of postconcussion syndrome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:243–250. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328344698b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ben-David BM, Nguyen LL, van Lieshout PH. Stroop effects in persons with traumatic brain injury: selective attention, speed of processing, or color-naming? A meta-analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17:354–63. doi: 10.1017/S135561771000175X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pielmaier L, Walder B, Rebetez MM, Maercker A. Post-traumatic stress symptoms in relatives in the first weeks after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2011;25:259–65. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.542429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eslinger PJ, Zappala G, Chakara F, Barrett AM. Cognitive impairments after TBI. In: Zasler ND, Katz DI, Zafonte RD, editors. Brain Injury Medicine: Principles and Practice. New York: Demos; 2007. pp. 779–90. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaas JH. Changing Concepts of Visual Cortex Organization in Primates. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaas JH. The evolution of the complex sensory and motor systems of the human brain. Brain Res Bull. 2008;75:384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suchoff IB, Kapoor N, Waxman R, Ference W. The occurrence of ocular and visual dysfunctions in an acquired brain-injured patient sample. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70:301–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen M, Groswasser Z, Barchadski R, Appel A. Convergence insufficiency in brain-injured patients. Brain Inj. 1989;3:187–91. doi: 10.3109/02699058909004551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lepore FE. Disorders of ocular motility following head trauma. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:924–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540330106022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlageter K, Gray B, Hall K, Shaw R, Sammet R. Incidence and treatment of visual dysfunction in traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1993;7:439–48. doi: 10.3109/02699059309029687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sabates NR, Gonce MA, Farris BK. Neuro-ophthalmological findings in closed head trauma. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1991;11:273–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scheiman M, Gwiazda J, Li T. Non-surgical interventions for convergence insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006768.pub2. CD006768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheiman M, Rouse M, Kulp MT, Cotter S, Hertle R, Mitchell GL. Treatment of convergence insufficiency in childhood: a current perspective. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:420–8. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31819fa712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, Kulp MT, Cooper J, Rouse M, Borsting E, London R, Wensveen J. A randomized clinical trial of vision therapy/orthoptics versus pencil pushups for the treatment of convergence insufficiency in young adults. Optom Vis Sci. 2005;82:583–95. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000171331.36871.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT) Study Group. The convergence insufficiency treatment trial: design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:24–36. doi: 10.1080/09286580701772037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rouse M, Borsting E, Mitchell GL, Kulp MT, Scheiman M, Amster D, Coulter R, Fecho G, Gallaway M. Academic behaviors in children with convergence insufficiency with and without parent-reported ADHD. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:1169–77. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181baad13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lavrich JB. Convergence insufficiency and its current treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:356–60. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833cf03a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cacho Martinez P, Garcia Munoz A, Ruiz-Cantero MT. Treatment of accommodative and nonstrabismic binocular dysfunctions: a systematic review. Optometry. 2009;80:702–16. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ciuffreda KJ. The scientific basis for and efficacy of optometric vision therapy in nonstrabismic accommodative and vergence disorders. Optometry. 2002;73:735–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barrett BT. A critical evaluation of the evidence supporting the practice of behavioural vision therapy. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2009;29:4–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2008.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serra A, Chen AL, Leigh RJ. Disorders of vergence eye movements. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24:32–7. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328341eebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation report of first admissions for 1992. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;73:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pankhania SR, Firth AY. The response AC/A ratio: differences between inducing and relaxing accommodation at different distances of fixation. Strabismus. 2011;19:52–56. doi: 10.3109/09273972.2011.578192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brautaset RL, Jennings AJ. Effects of orthoptic treatment on the CA/C and AC/A ratios in convergence insufficiency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2876–80. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mutti DO, Jones LA, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K. AC/A ratio, age, and refractive error in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2469–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hughes A. AC/A ratio. Br J Ophthalmol. 1967;51:786–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.51.11.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rosenfield M, Rappon JM, Carrel MF. Vergence adaptation and the clinical AC/A ratio. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2000;20:207–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alvarez TL, Vicci VR, Alkan Y, Kim EH, Gohel S, Barrett AM, Chiaravalloti N, Biswal BB. Vision therapy in adults with convergence insufficiency: clinical and functional magnetic resonance imaging measures. Optom Vis Sci. 2010;87:985–1002. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181fef1aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Y-F, Lee YY, Chen T, Semmlow JL, Alvarez TL. Behaviors, models and clinical applications of vergence eye movements. J Med Biol Engin. 2010;30:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cooper JS, Burns CR, Cotter SA, Daum KM, Griffin JR, Scheiman MM. Quick Refernce Guide. Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction. American Optometric Association. St. Louis: American Optometric Association; 2011. [August 16, 2012]. Available at: http://aoa.org/documents/QRG-18.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Raymond MJ, Bennett TL, Malia KB, Bewick KC. Rehabilitation of visual processing deficits following brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation. 1996;6:229–239. doi: 10.3233/NRE-1996-6309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taub MB, Rowe S, Bartuccio M. Examining special populations. Part 3: examination techniques. [August 16, 2012];Rev Optom. 2006 3:49–52. Available at: http://www.optometry.co.uk/uploads/articles/0b50a66ec71ccb8505ecb4676b685bc2_Taub3_10306.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoffman LG, Rouse M. Referral recommendations for binocular function and/or developmental perceptual deficiencies. J Am Optom Assoc. 1980;51:119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Granet DB, Gomi CF, Ventura R, Miller-Scholte A. The relationship between convergence insufficiency and ADHD. Strabismus. 2005;13:163–8. doi: 10.1080/09273970500455436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hamilton BB, Laughlin JA, Fiedler RC, Granger CV. Interrater reliability of the 7-level functional independence measure (FIM) Scand J Rehabil Med. 1994;26:115–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ottenbacher KJ, Hsu Y, Granger CV, Fiedler RC. The reliability of the functional independence measure: a quantitative review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1226–32. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.National Data and Statistical Center. Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems. [August 16, 2011];Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database Update 2012. Available at: https://www.tbindsc.org/Documents/2012%20TBIMS%20National%20Database%20Update.pdf.

- 75.Hammond FM, Malec JF. The Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems: a longitudinal database, research, collaboration and knowledge translation. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46:545–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sandhaug M, Andelic N, Bernsten SA, Seiler S, Mygland A. Functional level during the first year after moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: course and predictors of outcome. [August 16, 2012];J Neurol Res. 2011 1:48–58. Available at: http://www.neurores.org/index.php/neurores/article/viewFile/20/22. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stelmack JA, Frith T, Van Koevering D, Rinne S, Stelmack TR. Visual function in patients followed at a Veterans Affairs polytrauma network site: an electronic medical record review. Optometry. 2009;80:419–24. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Letourneau JE, Lapierre N, Lamont A. The relationship between convergence insufficiency and school achievement. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1979;56:18–22. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197901000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rouse MW, Borsting E, Hyman L, Hussein M, Cotter SA, Flynn M, Scheiman M, Gallaway M, De Land PN. Frequency of convergence insufficiency among fifth and sixth graders. The Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) group. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:643–9. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Porcar E, Martinez-Palomera A. Prevalence of general binocular dysfunctions in a population of university students. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74:111–3. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199702000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lara F, Cacho P, Garcia A, Megias R. General binocular disorders: prevalence in a clinic population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2001;21:70–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-1313.2001.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, Rouse M, Borsting E, Kulp M, Cooper J, London R, Wensveen J. Accommodative insufficiency is the primary source of symptoms in children diagnosed with convergence insufficiency. Optom Vis Sci. 2006;83:857–8. doi: 10.1097/01.opx.0000245513.51878.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rouse MW, Borsting EJ, Mitchell GL, Scheiman M, Cotter SA, Cooper J, Kulp MT, London R, Wensveen J. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in adults. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2004;24:384–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2004.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen CC, Pai YM, Wang RF, Wang TL, Chong CF. Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy from minor head trauma. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:e34. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2004.016311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Levy RL, Geist CE, Miller NR. Isolated oculomotor palsy following minor head trauma. Neurology. 2005;65:169. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000167288.10702.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kaido T, Tanaka Y, Kanemoto Y, Katsuragi Y, Okura H. Traumatic oculomotor nerve palsy. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:852–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fukushima K, Tanaka M, Suzuki Y, Fukushima J, Yoshida T. Adaptive changes in human smooth pursuit eye movement. Neurosci Res. 1996;25:391–8. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(96)01068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dhaliwal A, West AL, Trobe JD, Musch DC. Third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies following closed head injury. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:4–10. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000204661.48806.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dhital A, Pey T, Stanford MR. Visual loss and falls: a review. Eye (Lond) 2010;24:1437–46. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Freeman EE, Munoz B, Rubin G, West SK. Visual field loss increases the risk of falls in older adults: the Salisbury eye evaluation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4445–50. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Warren M. Pilot study on activities of daily living limitations in adults with hemianopsia. Am J Occup Ther. 2009;63:626–33. doi: 10.5014/ajot.63.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lew HL, Pogoda TK, Baker E, Stolzmann KL, Meterko M, Cifu DX, Amara J, Hendricks AM. Prevalence of dual sensory impairment and its association with traumatic brain injury and blast exposure in OEF/OIF veterans. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26:489–96. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318204e54b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]