Abstract

For many tissue engineering applications and studies to understand how materials fundamentally affect cellular functions, it is important to have the ability to synthesize biomaterials that can mimic elements of native cell–extracellular matrix interactions. Hydrogels possess many properties that are desirable for studying cell behavior. For example, hydrogels are biocompatible and can be biochemically and mechanically altered by exploiting the presentation of cell adhesive epitopes or by changing hydrogel crosslinking density. To establish physical and biochemical tunability, hydrogels can be engineered to alter their properties upon interaction with external driving forces such as pH, temperature, electric current, as well as exposure to cytocompatible irradiation. Additionally, hydrogels can be engineered to respond to enzymes secreted by cells, such as matrix metalloproteinases and hyaluronidases. This review details different strategies and mechanisms by which biomaterials, specifically hydrogels, can be manipulated dynamically to affect cell behavior. By employing the appropriate combination of stimuli and hydrogel composition and architecture, cell behavior such as adhesion, migration, proliferation, and differentiation can be controlled in real time. This three-dimensional control in cell behavior can help create programmable cell niches that can be useful for fundamental cell studies and in a variety of tissue engineering applications.

Introduction

In the body, cells grow within a complex and the bioactive scaffold known as the extracellular matrix (ECM) provides mechanical support to cells and biochemical cues that direct cell behavior.1 Specifically, the ECM is composed of several distinct families of molecules, such as glycosaminoglycans, proteoglycans, collagens, and non-collagenous glycoproteins. The ECM milieu varies compositionally and structurally between different tissue types, throughout different developmental stages of tissues, and during tissue regeneration and disease progression.2 The cell–ECM interactions are mediated by cell surface receptors, including integrins, immunoglobulins, and selectins, which, upon binding with cell adhesion motifs (referred to as ligands in this review), result in intracellular signaling cascades that coordinate various cell behaviors.3,4 In addition to the biochemical cues originating from the ECM, cells also probe and respond to matrix compliance. The compressive modulus or modulus of elasticity, E, is sensed by cells and affects cell behaviors such as migration and differentiation.5 Cell migration, for example, occurs as a result of dynamic integrin-ECM interactions facilitated by cycles of cell adhesion and de-adhesion. These cycles, in combination with the contractile cellular cytoskeleton, generate traction forces on ECM substrates resulting in cell spreading and/or migration. The ECM provides instructive differentiation signals to cells via the availability of proteins or various instructive motifs thereof. The ECM also plays an important structural role. For example, during tissue morphogenesis, motile cells undergo shape changes, while exerting forces on their neighboring cells and tissues to generate structures such as tubes, sheets, rods, and cavities.6 The instructive role of the ECM toward guiding cellular differentiation is exemplified by the mouse limb bud, where myogenic cell differentiation occurs as laminin and collagen IV protein expression temporally increases, whereas fibronectin (FN) protein expression decreases within the enveloping ECM.7 This remarkably complex, continually remodeled cellular microenvironment in which cells thrive and function in vivo is very challenging to recapitulate in vitro.

Designing biomaterials that can mimic the spatial and temporal complexity of ECM is very important to understand cell–material interactions and for developing materials that can be employed to mimic and/or control cell behaviors. Strategies have been employed to design ECM-mimicking cytocompatible biomaterials with biochemical8–10 and/or mechanical cues5,11–16 to recapitulate the spatial and temporal complexity of biological systems. Until recently, biomaterial designs generally focused on homogeneous and static incorporation of biochemical moieties,17 such as cell adhesion peptides,8,18 growth factors,19,20 cytokines,21 and neurotransmitters.22,23 Biomaterial designs were commonly based on the presentation of uniform mechanical properties within the biomaterial scaffolds.24 Static micro- and nanofabricated topographies have also been introduced into scaffolds to influence cell morphology, alignment, adhesion, migration, proliferation, and cytoskeleton organization.25–28 Nanoparticles and nanotubes, for example, have been integrated into biomaterials to generate nanobiomaterials that can modulate cell adhesion and spreading, and exhibit flexibility towards delivery of bioactive molecules.29,30

Recently, biomaterial platforms have been developed that provide dynamic modulation of biochemical and mechanical material properties to emulate physiologically relevant, real-time ECM changes. Most of these stimuli-responsive biomaterials are crosslinked, hydrophilic, biocompatible polymeric materials known as hydrogels.31,32 Hydrogels have great utility as ECM mimetics because they possess similar viscoelastic and diffusive transport properties and can be conveniently modified both mechanically and biochemically. In native tissues, diffusive transport properties are maintained via pores of different sizes arising as a result of cells embedded within the complex and tissue-specific ECM. Similar selective diffusive properties can be recapitulated within hydrogel scaffolds by controlling the hydrogel mesh size (i.e., crosslinking density).33 Also, just like the native ECM, hydogels possess both viscous and elastic behaviors. Hydrogels are >50% water by definition, which results in fluid behavior, but maintain their shape under deformation forces (e.g., elastic behavior).

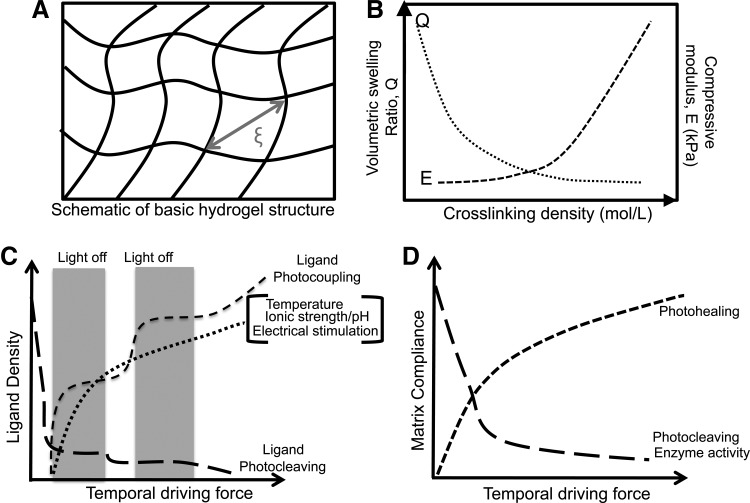

In this review, we summarize recent developments in the field of stimuli-responsive hydrogels and their applications within regenerative medicine as a means to control cell morphology, migration, differentiation, and viability in real time (Table 1). Before reviewing the mechanisms and specificities of stimuli-responsive cell–material interactions, we present an overview of the mechanisms of tuning hydrogel mechanical and biochemical cues and the differences between two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) hydrogel scaffolds. We will highlight parameters that affect hydrogel viscoelastic and diffusive properties, but will focus on (1) ligand density (Fig. 1C) and (2) matrix compliance of hydrogels (Fig. 1D), as these are the only two major material properties that have thus far been exploited to dynamically control cell behavior.

Table 1.

Different Stimuli Employed for Dynamic Manipulation of Hydrogels and Their Effect on Cell Behavior

| Stimuli | Substrate | Cell type | Cell behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Agarose hydrogels | DRGs | Cell migration57 |

| Neurite outgrowth57 | |||

| PEG hydrogels | hMSCs | Cell differentiation53 | |

| PEG hydrogels | MSCs | Cell adhesion and morphology52 | |

| PEG hydrogels | NIH3T3 fibroblasts | Cell migration55 | |

| PA hydrogels | NIH3T3 fibroblasts | Cell adhesion69 | |

| Electric current | Gold nanoparticle-coated PEI substrates | hESCs | Cell differentiation87 |

| Carbon nanotubes | Chondrocytes | Cell adhesion86 | |

| Cell proliferation86 | |||

| Boron nitride nanotubes | PC12 (cell line derived from pheochromocytoma of rat adrenal medulla) | Neurite outgrowth89 | |

| pH | Chitosan | HeLa cells (cell line derived from cervical cancer cells) | Cell attachment and detachment90 |

| Chitosan | HaCaT cells (human keratinocyte cell line) | Cell attachment and detachment90 | |

| Chitosan | H1299 cells (human nonsmall cell lung carcinoma cell line) | Cell attachment and detachment90 | |

| Chitosan | NIH3T3 fibroblasts | Cell attachment and detachment90 | |

| Chitosan | Primary corneal fibroblasts | Cell attachment and detachment90 | |

| Polyelectrolytes | Placenta-derived stem cell sheets | Cell attachment and detachment91 | |

| Temperature | PNIPAAm | MSCs | Cell sheet detachment98 |

| PNIPAAm-co-BMA | Bovine endothelial cells | Cell sheet detachment103 | |

| MDCK cells | Cell sheet detachment101,102 | ||

| PNIPAAm-co-PEG | NIH3T3 fibroblasts | Cell detachment99 | |

| P(NIPAAm-co-NAA) | NIH3T3 fibroblasts | Cell morphology104 | |

| Norland Optical adhesive 63 | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts C3H/10T1/2 | Cell alignment107 | |

| Cellular enzymes | PEG | MSCs | Cell differentiation120 |

| PEG | HFFs | Cell migration108 | |

| PEG | VICs | Cell morphology121 | |

| PLEOF-co-PEG | BMSs | Cell differentiation117 | |

| HA hydrogels | MSCs | Cell differentiation56 |

PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); hMSCs human mesenchymal stem cells; PA, poly(acrylamide); DRG, dorsal root ganglion; PEI, poly(ethyleneimine); hESCs, human embryonic stem cells; PNIPAAm, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide); PLEOF, poly(lactide-co-ethylene oxide-co-fumarate); VIC, valvular interstitial cells; HA, hyaluronic acid hydrogels; HFF, human foreskin fibroblasts; BMS, bovine bone marrow stromal cells.

FIG. 1.

(A) Schematic of the basic hydrogel structure. (B) The relationship between the hydrogel crosslinking density, matrix compressive modulus, E, and volumetric swelling ratio, Q. (C, D) The effect of different external stimuli on hydrogel properties. (C) The effect of changes in ionic strength, photocoupling, and electrical stimulation on ligand density presented to cells, and (D) an example (PLA-b-PEG-b-PLA hydrogel system, where PLA=poly(lactic acid) and PEG=poly(ethylene glycol)113) of the effect of changes in matrix compliance upon photohealing and enzymatic activity.

Mechanisms of Tuning Hydrogel Mechanics and Biochemistry

Fundamental hydrogel structure

Hydrogels are composed mainly of water, which fills the space between hydrogel crosslinks and allows for diffusion of solute molecules. Figure 1 describes the basic hydrogel structure showing critical hydrogel parameters such as the mesh size (ξ) (Fig. 1A) and the effect of crosslinking density on the hydrogel swelling ratio (Fig. 1B). Many hydrogel properties, including the equilibrium water content, compressive modulus, and diffusivity depend on the gel crosslinking density (ρx) which, in turn, governs the hydrogels' average mesh size, ξ (Fig. 1A). The Flory-Rehner equation is typically employed to relate the volumetric swelling ratio of the gel (Q), which is the inverse of the polymer volume fraction, to its crosslinking density (ρx). Assuming a highly swollen system (Q>10) and neglecting polymer chain ends, the Flory-Rehner equation simplifies to (Equation 1)34

|

(1) |

Here V1 is the molar volume of the solvent (V1=18 cm3/mol for water) and χ1 represents the interaction between the polymer and the solvent (0.426 for poly(ethylene glycol) [PEG]-water systems35). The same crosslinking density, and consequently, the hydrogels' mesh size also affect the diffusion of solutes within the matrix (Equation 2).

|

(2) |

where Dg is solute diffusivity in the hydrogels' swollen state, and D0 is the unhindered solute diffusivity in the swelling solvent, and rS is the radius of the solute. Thus, a decrease in the crosslinking density results in an increase in the equilibrium water content that in turn affects diffusion of molecules within hydrogels.

As mentioned previously, hydrogels are not simply elastic materials, but behave viscoelastically.36 This means that the mechanical properties of hydrogels are represented by a combination of stored (elastic) and dissipative (viscous) energy components. As a result, only dynamic mechanical analysis can provide complete information on hydrogel behavior by measuring mechanics as a function of deformation (stress or strain), a property known as the complex dynamic modulus (G*). Equation 3 describes the complex dynamic modulus (G*), where G′ is the elastic or storage modulus, G′′ is the loss modulus, σ* is the shear stress, and γ* is the shear strain.

|

(3) |

As far as cell–material interactions are concerned, it is currently assumed that hydrogel elasticity plays more fundamental roles in guiding cell behavior. As an example, cells probe hydrogel elasticity as they attach, spread, and migrate on or within hydrogels. Therefore, for practical purposes, the intrinsic resistance of hydrogels to applied stresses, measured by elasticity or the compressive modulus (E) is employed and controlled to direct cell behaviors dynamically. The compressive modulus, E, depends on the hydrogel microstructure and can be controlled by modulating the hydrogel crosslinking density (mesh size), as described by Equation 4 (Fig. 1B).

|

(4) |

Next, we describe the mechanisms for tuning hydrogel mechanics and biochemistry using parameters such as K and ligand density.

Mechanical modification of hydrogels

The hydrogel compressive modulus can be conveniently varied by changing the hydrogel crosslinking density (ρx), which in turn can be manipulated by (1) altering the weight percentage of macromers,37 (2) using structurally different (linear or branched) macromers for polymerization of hydrogels,17 or (3) altering the molecular weight of macromers. Unfortunately, the precise molecular mechanisms involved in the cellular response to the substrate modulus are still elusive.5 However, it is widely accepted that mechanical cues affect cell behavior through mechanically active structures inside the cells, particularly, the cytoskeleton. The cytoskeleton pushes or pulls on the substrate and responds to its compliance, which causes significant alterations in cell spreading. The cytoskeleton-generated traction forces are a result of mechanotransduction, which directly affects cell nuclei because the nuclei are connected to the cytoskeleton through lamins and nesprins.38 Peyton and coworkers identified the RhoA–ROCK pathway as an important regulator of osteogenic differentiation, where mechanical cues from the substrate are transduced and cause changes in the cellular phenotype.39 Also, it is plausible that cytoskeletal forces transmit directly to chromosomes, altering transcriptional events owing to modified physical accessibility of genes, resulting in changes in gene expression, causing cells to alter their differentiation patterns.40

Biochemical modification of hydrogels

Hydrogels are commonly modified with short amino acid sequences found in ECM proteins that elicit protein-analogous stimuli with superior in vivo stability and higher attainable ligand density.17 These cell adhesion motifs include (but are not limited to) RGD, YIGSR, IKVAV, LGTIPG, PDGSR, LRE, LRGDN, and IKLLI originating from the extracellular protein laminin; RGD and DGEA from collagen I; and RGD, KQAGDV, REDV, and PHSRN from FN.17 The bioactive ligand density immobilized on the material surface is one of the most crucial parameters that control cell–material interactions. In general, increase in ligand density on the surface results in greater cell adhesion and spreading. Among the above-mentioned examples of the cell-adhesive epitopes, the RGD ligand, located within many cell adhesion proteins, comprises the most universal and well-understood adhesion-receptor ligand system with respect to cell behavior. Fibroblast cell adhesion and spreading, for example, changes as the RGD density on the material surface changes between 10−3 fmol cm2 to about 104 fmol cm2.41 Specifically, cell spreading was found to be maximum at 1 fmol/cm2 with no further increase as the RGD density was increased up to 104 fmol cm2. Yet, focal contacts and stress fibers failed to form at RGD concentrations below 10 fmol cm2. This occurred because of changes caused by ligand–receptor interactions. Cell spreading as a result of increased RGD density occurs by clustering of the αvβ3 receptor on the cell surface and through the formation of focal adhesions, which in turn initiate downstream signaling pathways, such as microtubule-associated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK), which are involved in cell proliferation and differentiation.42 In most cases, matrix compliance and ligand densities are highly coupled, and together, they control cell responses such as cell spreading, cell shape changes, molecular organization, and cell differentiation.43–45

Hydrogels as 2D or 3D scaffolds

Hydogels may be employed as two-dimensional (2D) or three-dimensional (3D) substrates for cell culture. Two-dimensional hydrogels, as the name suggests, are typically pre-fabricated structures upon which cells can be seeded. Two-dimensional systems provide convenient means for exploration of cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, and have given rise to significant findings in the field of cell–material interactions. For example, Engler et al.46 and Discher et al.5 demonstrated that mechanical stiffness controls lineage specifications (human mesenchymal stem cells [hMSCs]) of stem cells. However, 3D hydrogel scaffolds provide a more accurate representation of cells in situ as cells are embedded within hydrogels, thereby presenting cells with a more in vivo-like microenvironment. The potential of hydrogels as 3D scaffolds to study fundamental cell–material interactions and for tissue-engineering applications has been recently reviewed in a comprehensive manner by Owen and Shoichet47 as well as Tibbitt and Anseth.48

Stimuli for Real Time Manipulation of Hydrogels

Light

Phototunability: mechanisms and chemistry

In situ manipulation of hydrogel networks offers an attractive platform to change material properties either on the surface of 2D substrates (micron- or nanoscale modification)25 or within 3D hydrogel scaffolds.49,50 Specifically, light-activated reactions offer an opportunity to control the spatiotemporal presentation of biochemical and mechanical cues that cells can recognize and respond to in real time. The light-activated manipulation of material properties occurs via focused light sources (using lasers and light emitting diodes) by altering the wavelength, intensity, and exposure time. Both single and multiphoton light sources can control material properties from the nanoscale to macroscale, where the spatial resolution within the gel is controlled by the focal volume, which for Gaussian laser beams, is governed by lateral (wxy) and axial (wz) 1/e radii,51,52 according to Equations 5 and 6, where λ is the wavelength of light used at a given numerical aperture NA, and n is the refractive index of the material.

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

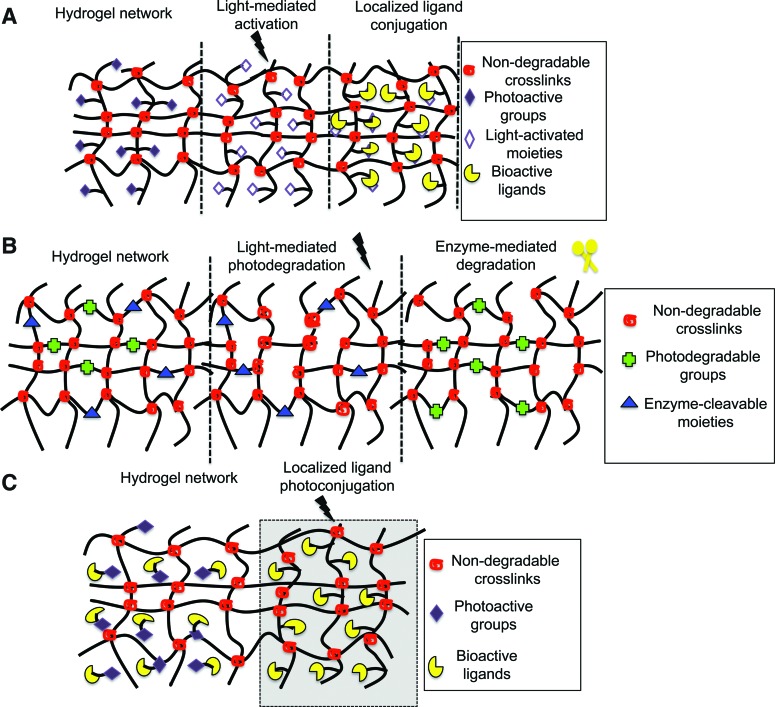

Changes in hydrogel mechanical properties occur using two approaches. One approach is through incorporation of photochemical groups within gel crosslinks that are cleaved by UV light, resulting in decrease in the hydrogel crosslinking density (ρx) and compressive modulus upon light exposure (Figs. 1B and 2B, Equation 3).53 Conversely, light-activated modification can also occur via incorporation of groups that form additional crosslinks between polymer chains, resulting in increased material compliance (Fig. 1D).54 Since matrix mechanics greatly affects cell fate,5 phototunable biomaterials have been used to control cell differentiation, adhesion, and morphology.53,55 Additionally, changes in the ligand density have been demonstrated using spatiotemporally controlled light-mediated coupling or removal of biologically active ligands from hydrogels (Fig. 2A).56 The photoreactivity in hydrogels has been demonstrated through incorporation of nitrobenzyl ether-derived molecules. The nitrobenzyl group is cytocompatible, possesses great photolytic efficiency, and is susceptible to single and multiphoton photolysis.52,53,57–60 By utilizing the appropriate combination of gelation chemistry and nitrobenzyl moiety, hydrogels have been designed to photodegrade53,55 or photoheal in real time.61 Hydrogels of various compositions, that is, PEG, poly(acrylamide) (PA), and agarose have been rendered phototunable via chemical modification of macromolecules.

FIG. 2.

Schematic of (A) photoactivation followed by ligand immobilization, (B) photodegradation and enzyme-responsive degradation, (C) photoimmobilization of ligands. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Photodynamic modulation of ligand density

Agarose hydrogels are attractive biomaterials for tissue engineering because they resist protein adsorption, are biocompatible, have remarkable ranges of achievable moduli, and can be dynamically tuned to provide ligands for cell–material interactions. To modulate cell–material interactions, cell adhesive epitopes derived from laminin, such as YIGSR, IKVAV, and RGD, have been incorporated into agarose hydrogels.62–64 Agarose gels allow for photomodification because of their optical transparency. For example, Luo and Shoichet devised a strategy to modify agarose hydrogels in three dimensions using light,57 wherein the ligand density presented to cells was altered in real time. In their strategy, bulk 3D agarose was first activated and reacted with 2-nitrobenzyl-protected cysteine (NBC), a photosensitive agent that, upon light exposure, presents free thiols. It has been shown that NBC-modified agarose hydrogels exhibit no cytotoxicity or inhibitory effects on cell growth.57 After exposure, free thiol groups were subsequently reacted with maleimido-terminated cell adhesive peptides (RGDS) to provide cell–material interactions. Free thiol-functionalized channels were created in NBC-modified agarose gels in three dimensions and fluorescently labeled maleimide-terminated GRGDS was employed to examine the distribution of ligands within the channels. The diameters of the channels were 150–170 μm over a 1-mm depth, corresponding to the focal spot size of the laser employed (160 μm). However, it was observed that the transmittance of laser light through NBC-modified agarose hydrogels decreased with the gel depth and NBC concentration. Using phototunable agarose hydrogels, Luo and Shoichet also demonstrated that 3D RGDS-modified agarose could promote dorsol root ganglion (DRG) cell migration and neurite outgrowth within hydrogels.57 Specifically, DRGs migrated and extended neurites only into RGDS-modified agarose channels and not into the unmodified agarose.

PEG is another hydrophilic polymer commonly used to form hydrogels. Various photopolymerization strategies such as chain growth polymerizations,65 step-growth polymerizations,66 and mixed-mode polymerizations67 have been employed to fabricate PEG-based hydrogels.68 PEG hydrogels are non-toxic, non-immunogenic, and resist protein adsorption and therefore are not recognized by cells.68 However, similar to most hydrogel systems, PEG hydrogels can be biochemically modified through incorporation or photolysis of cell adhesion epitopes (or ligands) to alter cell–material interactions. Real-time modulation of ligand density has been demonstrated via two modes: (1) light-mediated activation of photolabile moieties in hydrogel networks, which allows ligand conjugations in light-activated regions (Fig. 2A), and (2) asymmetrically caging or capping of cell adhesion epitopes by a photolabile group (Fig. 2C). Upon exposure to light, crosslinks break and epitopes become uncaged, providing access to cell–material interactions. While these two mechanisms are different, both allow dynamic changes in PEG functionality upon light exposure, which translate into dynamic changes in cell behavior.

Photodynamic modulation of both matrix stiffness and ligand density

There are several photo-induced strategies utilized to modify the mechanics of hydrogels. In one approach, PEG-based photodegradable crosslinking macromers comprised of PEG, photolabile moieties, and acrylic end groups were synthesized. Upon polymerization, PEG chains were crosslinked such that the photolabile moiety was incorporated within network crosslinks. When exposed to light, crosslinks were cleaved, causing a subsequent decrease in the hydrogel compressive modulus. Photo-modulated degradation of hydrogels has been shown to affect cell morphology.53 For example, hMSCs encapsulated within the densely crosslinked hydrogel network exhibited rounded morphologies, but cells became more elongated within hydrogels when the crosslinking density was reduced via photodegradation. Specifically, light of 365 nm wavelength at 10 mW/cm2 was used for 480 s to degrade gels such that ρx/ρxo ∼ 0.04 (where ρxo and ρx represent crosslinking density before and after light exposure). hMSC cytoskeletal organization was also affected by the extent of photodegradation.52 MSCs cultured on similar photodegradable hydrogels also formed organized cytoskeletal networks. Following seeding, substrates were photoeroded exclusively at the cell–material interface to selectively disrupt focal adhesions via erosion of cell-adhesive RGD epitopes. Selective disruption of cell–material interactions in the areas of irradiation caused cells to retract and undergo cytoskeletal reorganization and cell shape changes.

In another study, DeForest and Anseth showed the assembly of PEG hydrogels, where both photoconjugation and photocleavable reactions were employed to spatiotemporally regulate material properties. PEG hydrogels were formed via copper-free azide-alkyne click reactions using PEG-tetracycloctyne and bis(azide)-di-functionalized polypeptide as the reactants.55 Allyloxycarbonyl (alloc) functionalities were introduced into bis(azide)-di-functionalized polypeptides using lysine(alloc). The alloc-functionalities of lysine allowed photocoupling to thiol-containing compounds such as cysteine-containing peptides. Subsequently, in the presence of visible light, thiol-containing biomolecules (RGD in this case) were conjugated to the pendant alloc functionalities (Fig. 2A). In the same study, photo-induced degradation of hydrogel networks was demonstrated. This was accomplished by including photodegradable nitrobenzyl ether moieties within the azide macromers in addition to the alloc-lysine.55 The photo-induced changes in material properties affected encapsulated cell behaviors. After 2 h, physical channels were photo-eroded radially from fibroblast-laden fibrin clots (NIH3T3s) encapsulated within these click hydrogels (due to the nitrobenzyl ether moiety between the crosslinks) via multiphoton photodegradation. This erosion resulted in collective cell migration along the channels. Additionally, when only specific regions of the gels were functionalized with RGD via thiol–ene coupling, cells migrated selectively into RGD-laden hydrogel channels, but not into unfunctionalized channels.

Fairbanks et al. also reported a unique approach to photodegrade PEG hydrogels. In their approach, hydrogels were formed by oxidation of thiol-functionalized PEG, forming disulfide crosslinks. Upon exposure to photoinitiator and light (120 s of 10 mW/cm2 at 365 nm for 2-mm-thick hydrogels), hydrogels were photodegraded due to radical-mediated multiple fragmentation and disulfide exchange reactions.61 By limiting photoinitiator concentrations, similar PEG hydrogels have been demonstrated to exhibit self-healing properties.61 This occurs when the numbers of radicals generated upon UV exposure are significantly lower than the numbers of sulfur atoms in the gel. This causes a disulfide exchange at the interface of prefabricated gels (in close contact), which results in the merging of two independent hydrogels into one structure. Although not yet shown, this decrease in crosslinking density as a function of UV light exposure could be exploited both spatially and temporally and has great potential to affect cell behavior in real time. Moreover, photohealing hydrogels present an opportunity to reconstruct complex tissue regions/structures, such as osteochondral tissue interfaces, where tissues could be evolved in separate gel architectures, and then seamlessly integrated.

PA hydrogels have also been widely used to regulate cell–material interactions. This is because PA gels offer favorable optical and elastic properties.5,45 To develop photomodulatable PA-based hydrogels, gels were prepared by first reacting PA with hydrazine hydrate to create poly(acrylamide acryl hydrate) (PAAH). Using these PAAH macromers, gels were formed using 4-bromomethyl-3-nitrobenzoic acid as the crosslinker (BNBA) (a source of the phototunable nitrobenzyl moiety), where the bromomethyl group of BNBA undergoes nucleophilic reactions with amines via 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide chemistry. To provide cell recognition, gel substrates were conjugated with a thin layer of fibronectin (FN). Photoirradiation resulted in gel instantaneously softening due to UV photolysis of nitrobenzyl groups present in the crosslinkers (Fig. 2B). Photodegradation of PA gels and subsequent decreases in gel stiffness significantly inhibited NIH3T3 fibroblast spreading.69 While the hydrogel compressive modulus decreased by 20%–30% (from 7.2 to 5.5 kPa), the spread cell area was reduced by 12%±1% compared to before UV exposure.

Recently, Guvendiren and Burdick reported a stepwise approach to fabricate hyaluronic acid real-time tunable hydrogels that undergo UV-induced photocrosslinking. These tunable hydrogels were demonstrated to have moduli ranging between 3–30 kPa. Using hMSCs, the short-term (minutes-to-hours) and long-term (days-to-weeks) cell responses to dynamic stiffening hydrogels were investigated.54 When substrates are stiffened, hMSCs increased their area from ∼500 to 3,000 μm2 and exhibit greater traction forces (from ∼1 to 10 kPa) over a timescale of hours. For longer cultures (up to 14 days), hMSCs selectively differentiated as a function of when stiffening was induced. For example, adipogenesis was favored for stiffening that occurred after hMSCs were cultured on soft substrates for 7 days, followed by 7 days of culture in stiffening conditions, whereas osteogenesis differentiation was favored for stiffening that occurred earlier (e.g., after 3 days).

Electric current

Mechanisms of electrical stimulation

Electrical stimulation (ES) is another powerful external stimuli that can be utilized to dynamically control cell behavior. ES affects cells differently depending on the cell type. For example, under an applied potential difference, osteoblast-like cells migrate toward negative electrodes, whereas osteoclasts migrate toward positive electrodes.70 Several in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that ES plays a critical role in neurite extension and regeneration of functional nerve connections,71,72 promoting nerve regeneration in gaps less than 7 mm.73 ES is also capable of inducing changes in cell shapes and for promoting cell alignment along the direction of ES application.74 Electroconductive biomaterials are generally made up of polymeric blends of conductive materials (such as poly(HEMA), poly(aniline), poly(thiophene), poly(pyrrole) [PPy], and metallic nanoparticles) and hydrogels. Although it is established that ES affects cell behavior (e.g., to enhance nerve regeneration) both in vitro75–77 and in vivo,78,79 the mechanism of this effect is not completely understood. One hypothesis is that an electrical stimulus alters local electrical fields of ECM molecules, changing protein adsorption, which in turn affects cell behavior as depicted in Figure 1C. For example, it has been shown that the ES increases FN protein adsorption to PPy. It is also speculated that ES causes increased synthesis and/or secretion of ECM molecules required for neurite outgrowth.80 This increase in cell-adhesive ligand density upon ES can lead to increases in neurite extension.81 Another hypothesis evolves from the ability of cytoplasmic biopolymers such as pro-collagen, RNA, and DNA to store charges. Thus, perturbations in ECM electric fields via externally applied ES can alter the conformation and orientation of these biomolecules within cells, by enhancing cellular enzyme-driven reactions through electroconformational coupling mechanisms, ultimately affecting downstream signaling within cells.82

Electrically-stimulated modulation of ligand density

Various electrically conductive materials have been developed and used to electrically stimulate cells. Recently published reviews83,84 describe in great detail the capabilities of electroconductive hydrogels containing poly(aniline), PPy, poly(thiophene), poly(caprolactone fumarate),76 and poly(2-methoxy-5-aniline sulfonic acid),85 to promote cell adhesion, growth, and proliferation83 upon ES. Therefore, to avoid redundancy, here we will focus on nanostructured materials (e.g., nanoparticles such as gold nanoparticles77 and carbon nanotubes [CNT]86) that have been used as ES-responsive materials to dynamically affect cell behaviors.

Electrically-stimulated modulation of nanostructured biomaterials to control cell behavior

Through inclusion of a variety of surface dopant ions, it has been established that gold nanoparticles have great ability to directly deliver ES to cells. For example, gold nanoparticles deposited onto poly(ethyleneimine) (PEI)-coated surfaces have been shown to promote neurite outgrowth upon application of alternating ES.77 Gold resistance is lower than tissue culture growth media solutions; thus, upon ES, electrons pass through gold-coated surfaces submerged in tissue culture media and affect neurite extension. In another study, gold nanoparticles modified with FN and PEI were exploited to induce stem cell differentiation of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) using ES.87 To evaluate hESC differentiation into different lineages, specific gene markers such as keratin 15 (ectoderm), T gene (mesoderm), and amylase (endoderm) were utilized. Keratin 15 and amylase expression in hESCs exposed to ES were not as great as other cells on control non-stimulated substrates. However, the upregulation of T gene expression suggested that ES stimulation results in preferential differentiation of hESCs into mesodermal phenotypes. Specifically, upon ES, hESCs on gold nanoparticles modified with FN and PEI differentiated into osteogenic phenotypes as indicated by increases in expression of bone-associated proteins such as collagen type 1 and core-binding factor α1.

CNT have also been incorporated into biomaterials to offer unique surface energetics, which can promote specific cell–ligand interactions useful to control cellular functions. For example, ES of electrically conductive (CNT)/polycarbonate urethane (PCU) composites have been shown to enhance chondrocyte proliferation compared to ES of pure PCU.88 Chondrocyte adhesion and cell density increased more than 50% after 2 days on CNT/PCU composites upon exposure to ES, compared to no stimulation. It was hypothesized that increased nanosurface roughness, surface energy, and conductivity of nanocomposites promoted a greater initial FN adsorption, which mediated chondrocyte–material interactions. In another study, ES was used to stimulate PC12 cells via piezoelectric boron nitride nanotubes, which resulted in a 30% greater neurite outgrowth as compared to non-ES control cultures.89

pH

Mechanisms of pH responsiveness

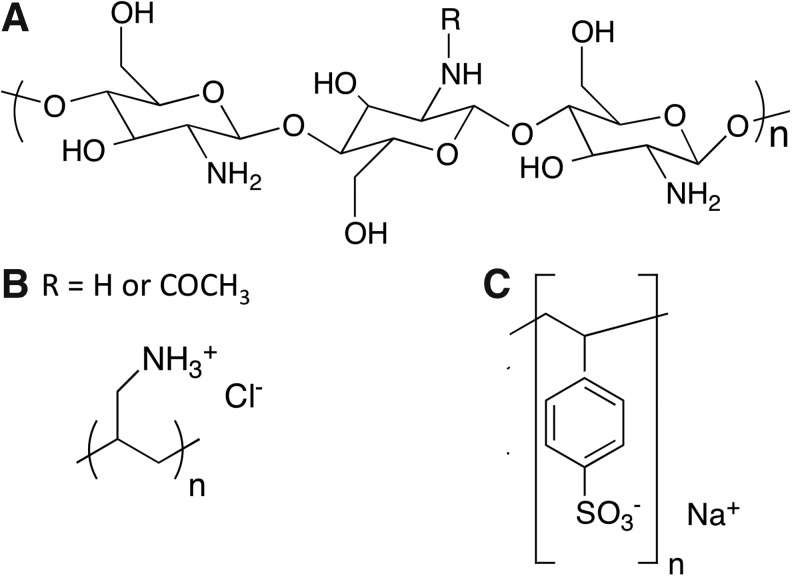

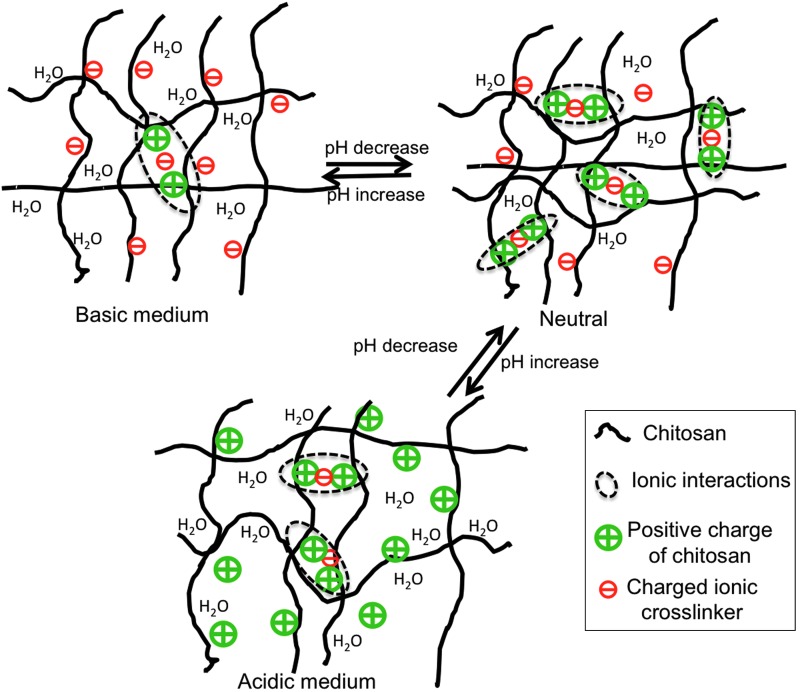

Chitosan hydrogels and poly(electrolyte) multilayer-coated materials have also been employed to dynamically control cell attachment90 and detachment91 simply by changing the pH of the surrounding media. Although widely used for drug-delivery applications, pH-responsive materials have seen far fewer applications in tissue engineering. This is due to the scarcity of available materials exhibiting changes in physical properties within physiologically relevant pH regimes (∼ 6 and 7.4). Chitosan is one of the few biopolymers that is pH-responsive at physiologically relevant pH.92 This polysaccharide possesses multiple amine groups (from glucosamine residues) and has an isoelectric point of pH=7.493 (Fig. 3A). Slight variations in pH (between 6.99 and 7.20) have been shown to affect cell–chitosan interactions via changes in FN protein adhesion (Fig. 4). Chitosan surfaces become positively charged due to protonation of primary amine groups when the pH is lower than 7.4 (Fig. 4). As FN has a net negative charge at physiological pH,94 there is increased FN adsorption (i.e., increased ligand density) and cell adhesion when the pH of chitosan surfaces is below 7.4.

FIG. 3.

Chemical structures of pH-responsive polymers that have been used to control cell behavior (A) chitosan (B) poly(allylamine) hydrochloride, and (C) poly(styrene sulfonate).

FIG. 4.

Schematic of pH-sensitive changes in the chitosan hydrogel structure as the medium pH changes from basic to neutral to acidic. The sketches are adapted from the work of Berger et al.92 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

pH-controlled modulation of ligand density

Chitosan (structure shown in Fig. 3A) hydrogels have been extensively utilized to control cell behavior in real time. For example, HeLa cells, a human cervical carcinoma cell line, attached and spread favorably on chitosan at physiological pH, but exhibited rapid (<1 h) and nearly complete detachment at pH 7.65.90 The pH responsiveness of chitosan has also been demonstrated to effectively control attachment/detachment of other cell types such as HaCaT (the human keratinocyte cell line), H1299 (the human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line), NIH3T3 fibroblasts, and primary corneal fibroblasts.90 Other pH-responsive materials that have also been explored to control cell behavior include poly(electrolyte) multilayers. Thin films consisting of layer-by-layer assembly of cationic poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (Fig. 3B) and anionic poly(styrene sulfonate) (Fig. 3C) on conductive indium tin oxide electrodes have been employed to trigger pH-responsive release of placenta-derived MSC sheets.91 Resulting stem cell sheets exhibited high viability and retention of their phenotypical profiles and differentiation potentials. Cell sheet detachment was demonstrated both with local and global pH changes. Intact tissue-like cell sheets with a preserved ECM95 can be used individually or can be layered/rolled to create tissues of larger sizes or with a defined laminar organization, an approach known as “cell sheet engineering.”96 These cell sheets could also be patterned and assembled to mimic the microarchitecture of native tissues, crucial for functional tissue regeneration.

Temperature

Mechanism of thermoresponsiveness

Temperature-responsive biomaterials employed to control cell behavior are almost exclusively prepared using poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAAm) (Fig. 5A) and its derivatives as the phase transition behavior of PNIPAAm occurs at physiological temperatures. Other biocompatible polymers such as poly(caprolactone), poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), and poly(styrene) exhibit too high of phase transition temperatures (between 40 °C and 60 °C) to be relevant substrates for controlling cell behavior. When above 32 °C, PNIPAAm undergoes a reversible lower critical solution temperature (LCST) phase transition from a swollen, hydrated state to a collapsed, dehydrated state, losing about 90% of its mass. At 37 °C, PNIPAAm chains are collapsed and hydrophobic, promoting protein adsorption, which provides cell-adhesive epitopes to establish cell–material interactions. When the temperature is lowered below its LCST, PNIPAAm becomes hydrophilic due to hydrogen bonding with water, resulting in protein and cell detachment. Consequently, cell culture substrates coated with thermoresponsive polymers can be used to harvest cell sheets with the undamaged ECM, simply by altering substrate temperatures around the LCSTs.97–99 Cell sheets formed with the aid of thermoresponsive polymers, in contrast to the use of enzymes, minimize the damage to cells and their ECM, thus preserving biological functions.

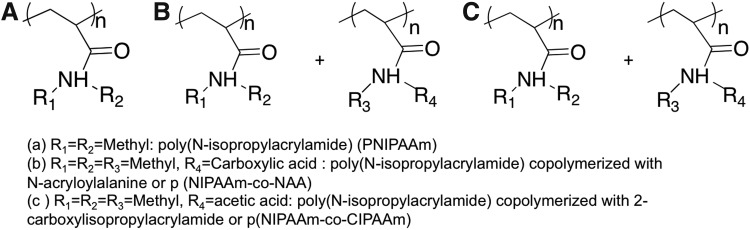

FIG. 5.

Chemical structures of thermoresponsive polymers that have been used to control cell behavior (A) poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (B) poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymerized with N-acryloylalanine, and (C) poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) copolymerized with 2-carboxylisopropylacrylamide.

Thermally stimulated modulation of ligand density

Thermoresponsive biomaterials undergo dramatic changes in shape or hydrophilicity in response to temperature, thereby dynamically affecting cell behaviors.100 PNIPAAm substrates can be utilized to recover confluent cell sheets through temperature reduction. Examples include, but are not limited to, MSCs, bovine endothelial cells, Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, and NIH3T3 fibroblasts.98,101–103 Graft copolymers comprised of PNIPAAm and PEG have also been employed to alter cell behavior dynamically. Fibroblasts adhered, spread, and proliferated on PNIPAM-PEG copolymers at 37 °C, but became completely detached and were recovered as single cell sheets upon temperature reduction to 25 °C.99 The thermoresponsive behavior of PNIPAAm has also been exploited in FN-modified PNIPAM-based hydrogels (i.e., FN-modified p(NIPAAm-co-NAA, where NAA=N-acryloylalanine) [Fig. 5B]) where, instead of cell attachment or detachment, cells were stretched as a result of temperature cycling. This happened because the volume of FN-modified p(NIPAAm-co-NAA) gel changed equibiaxially in response to reductions in temperature. Therefore, NIH3T3 fibroblasts on the FN-modified p(NIPAAm-co-NAA) gel substrates did not detach, but were stretched as the temperature was cycled between 37 °C to 25 °C.104 This mechanical stimuli-induced deformation of the NIH3T3 cell shape also led to activation of the intracellular signaling pathway, causing cells to form filopodia-like structures due to actin polymerization. Biofunctionalized thermoresponsive interfaces have also been prepared using N-isopropylacrylamide and its carboxyl-derivative, 2-carboxyisopropylacrylamide (CIPAAm) (Fig. 5C). These copolymers therefore offer a carboxylic acid moiety (CIPAAm) to allow for grafting of RGDS to the gels. RGDS functionalization promoted attachment of bovine carotid artery endothelial cells. In addition, recovery of cells as viable cell sheets was demonstrated by reducing the temperature from 37 °C to 25 °C.105

In addition to changes in hydrophilicity, thermal stimuli can also result in surface topographical changes by exploiting shape-memory polymers. Shape-memory polymers are active materials that have the ability to memorize permanent shapes through permanent crosslinks. By vitrification or crystallization, the material can be altered to a temporary shape. Upon introduction of changes in temperature, solvent pH, or ES, shape-memory polymers revert back to their original shapes. Changes can be employed to control cell micropatterning or cell alignment and have been demonstrated using a commercially available non-cytotoxic shape memory polymer (Norland Optical Adhesive 63).106 Norland Optical Adhesive 63 changes its surface topography from grooved to flat as the temperature cycled between 30 °C and 37 °C, affecting cell alignment. Cell alignment of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (C3H/10T1/2), when plated on these surfaces, exhibited thermal responsiveness.107 Both cell bodies and cytoskeletal microfilaments aligned along grooves of the temporary topographies of polymer surfaces at 37 °C, but the alignment was lost upon transition to flat topographies upon reduction in temperature. This transition did not affect cell viability or attachment.107

Enzymes

Mechanism of enzymatically modulated hydrogels

Hydrogels have also been engineered to remodel in response to cell-released enzymes, including proteases108,109 and hyaluronidases.110 Enzymatically degradable sequences utilized in hydrogels include, but are not limited to, GGLGPAGGK (degraded by collagenase),111 AAAAAAAAAK,111 AAPVR and AAP(Nva)112,113 (degraded by elastase), and GPQGIWGQ, GPQGIAGQ, and GPQGILGQ (degraded by collagenase and various matrix metalloproteinases [MMPs] such as MMP-1, −2, −3, −7, −8, and −9).108,114 Cellular degradation of hydrogels containing these sequences is dependent upon a number of factors, including the cell type, substrate, and substrate sequence. Therefore, through alteration of these factors, the degradation rate can be tuned. The enzyme activity results in the crosslink cleavage, which has been exploited to reduce both the ligand density and hydrogel compressive modulus (Fig. 2B).

Cellular enzyme-dictated modulation of ligand density

Incorporation of cellularly degrading substrates within hydrogels has been employed to control hMSC differentiation via temporal variation of ligand densities. Studies have shown that hydrogel-encapsulated hMSC differentiation initially requires cell–material interactions to maintain hMSC viability.115 Gene expression profiles have suggested that during the first week of chondrogenesis, hMSCs upregulate FN production, which provides adhesive sites for cell condensation and cell signaling, resulting in the early stages of chondrogenic determination. To mimic this process in vitro, Salinas and Anseth designed a peptide sequence comprised of a MMP-13 substrate, and a ubiquitous FN-mimic, RGD.109 This peptide sequence was then covalently coupled to the PEG hydrogels. Over time, hMSCs encapsulated within hydrogels, including the enzymatically degradable RGD moieties exhibited a much greater chondrogenesis owing to the temporal decrease in the availability of RGD. This is in contrast to the much reduced chondrogenic differentiation exhibited by hMSCs encapsulated within PEG hydrogels with control, nondegradable RGD sequences. Specifically, a 10-fold increase in GAG (glycosaminoglycan) production consistent with chondrogenic differentiation was observed in the RGD-cleavable hydrogels compared to the hydrogels with constant RGD availability.

Cellular enzyme-dictated modulation of matrix stiffness

Hydrogels have also been developed that respond to cellular enzymes by cleavage of substrate-containing hydrogel crosslinks. This degradation causes a reduction in matrix compliance, which affects cell behavior108–110 (Fig. 2B, Equation 3). Lutolf et al. was first to utilize MMP-degradable hydrogels to generate this family of enzyme-responsive biomaterials. These materials were formed via Michael-type addition reactions between PEG-tetravinylsulfone, mono-cysteine-containing integrin-binding peptides, and bis-cysteine containing MMP-sensitive peptide sequences (GPQG↓IWGQ). Hydrogels were used to encapsulate human foreskin fibroblast cells entrapped in fibrin.108,116 It was found that gels that contained MMP-degradable crosslinks exhibited a significantly greater cell invasion (>1 mm in 1 week) as compared to control, nondegradable hydrogels (100 μm in 1 week). He and Jabbari also developed in situ crosslinkable polymers composed of poly(lactide-co-ethylene oxide-co-fumarate) (PLEOF) macromers using ultralow molecular weight poly(L-lactide) and PEG units linked by a fumaryl unit using MMP-13 cleavable (sequence: QPQGLAK) crosslinks.117 Bone marrow stromal cells were encapsulated in peptide-crosslinked PLEOF hydrogels. By controlling the ratio of the peptide to nondegradable methylene bisacrylamide crosslinker, the MMP-13 concentration, cell-hydrogel incubation time, control over the overall hydrogel degradation rate, and subsequently, the behavior of encapsulated cells, were demonstrated. About 84% of encapsulated cells were viable after 1 week of incubation in osteogenic media and cells differentiated to osteoblasts as indicated by the production of mineralized tissues, alkaline phosphatase activity, and calcium content. Other cellularly responsive hydrogel systems have also shown the potential to affect cell behavior in real time. For example, self-assembled peptide systems formed under physiological conditions have been shown to direct neural progenitor cell differentiation118 and also permit hMSC chondrogenesis in 3D.119

PEG-peptide hydrogels with variable cell-dictated degradation were also formed using different ratios of MMP-degradable (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK) and nondegradable crosslinkers. The cell adhesion epitope (CRGDS) was also incorporated within hydrogels and the differentiation, viability, and proliferation of encapsulated MSCs were evaluated. For 100% degradable substrates over 14 days of culture, MSC density decreased to 55% of its initial value due to dramatic degradation and cell migration from the hydrogels. Also, cell morphology varied dramatically within degrading hydrogels. For example, cells spread less in hydrogels with fewer MMP-degradable crosslinkers. Encapsulated MSCs cultured in osteogenic or chondrogenic media extended protrusions, while cells in adipogenic media remained in rounded morphologies, typical of differentiating adipocytes.120 Interestingly though, upon encapsulation within MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels, valvular interstitial cells (VIC), cells that reside within heart valves, were found to proliferate and migrate similarly to nondegradable controls. Hydrogel degradation, however, did affect VIC morphology with cells within degradable hydrogels exhibiting greater process extensions.121 This change in VIC morphology was, therefore, a direct result of decreases in hydrogel crosslinking density.

Challenges Associated with Hydrogels and Potential Alternatives

Although hydrogels have been very successful in emulating the ECM and for controlling cell behaviors dynamically, they suffer from challenges that limit their utility. For example, hydrogels are mechanically weak, that is, very soft (E ∼1–100 kPa) and cannot withstand large deformations or stresses within the body.36 Thus, they are uniquely suited to emulate cell–material interactions in compliant tissues (e.g., muscle, cartilage, adipose tissues, and certain organs), but not able to recapitulate forces typical of harder tissues such as bone. Hydrogels lack a complex microvascular system, which is essential for mimicking larger tissues to allow adequate exchange of nutrients and wastes so as to maintain their viability and function.122 Additionally, hydrogels cannot completely mimic the anisotropic composition of tissues, which is important especially for their in vivo translation to tissue regeneration applications. As an alternative, hybrid hydrogels with nanoarchitecture (inclusion of nanotubes) combined with cells can be used to generate three-dimensional implanatable scaffolds.

Based on the specific application, the hydrogel composition, dimensions, matrix compliance, and biochemical properties must be selected to ensure proper control of cell behavior. Although all hydrogels discussed herein exhibit biocompatibility, it is critical to verify if these materials initiate immunogenic reactions in the body when the stimulus is employed. Additionally, careful selection of the hydrogel polymerization strategy is very important when employing these materials for cell studies. For example, it is known that Michael-type addition reactions to form hydrogels may result in a disulfide bond formation, which can lead to nonstoichiometric reactions between macro(mono)mers, resulting in undesired, suboptimal hydrogel properties.123 Alternatively, employing radical-initiated step-growth66 and chain-growth115 PEG polymerization strategies can lead to spatially and temporally controlled and relatively uniform gel networks. For cell encapsulation studies, polymerization strategies that allow even and well-dispersed cell seeding maybe desirable; thus, rapid gelation approaches should be employed. Also, most stimuli-responsive hydrogels have slow response times (mainly documented in drug delivery applications) and exhibit significant hysteresis with the on and off states regardless of the stimuli employed.124 Although not so evident in cell studies, careful characterization of hydrogels is important when employing stimuli-responsive hydrogels for in vivo applications.

Conclusions and Future Directions

To successfully design biomaterials, such as hydrogels, to emulate important dynamic tissue regeneration processes in vivo to attempt to deconstruct cell signaling, it is vital to consider the interplay between therapeutic cells/tissues and environmental cues. Additionally, from a fundamental perspective, it is important to understand how cells dynamically respond to both internal and external stimuli to control their behaviors and functions. Despite many advances in the field of hydrogel design and in situ hydrogel manipulation, it is currently inconceivable to mimic all the complexities associated with in vivo cell-ECM interactions. Nevertheless, the current and ongoing evolution in material science and engineering may provide even more sophisticated methods to allow for dynamic control of biochemical and physical gel properties, and experiments to be performed and interpreted with unprecedented in vivo mimicry. Recently developed biomaterials such as shape-memory elastomers125 and polymers,107 wrinkling hydrogels,126 and shape-switching polymers127 hold great promise for use to systematically monitor cell behavior in controlled, yet dynamic, conditions. Sophisticated noninvasive stimuli such as acoustic radiation forces associated with ultrasound standing wave fields are also being developed to control the spatial distribution of cells and ECM proteins within engineered tissues.128 These advances will help to further recapitulate in vivo tissues and allow us to intelligently motivate the use of different stimuli and substrates for a number of tissue-engineering applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Institute of Health (Grant No. NIH P30A1078498) (Development Center for AIDS Research) and the University of Rochester for funding. We would also like to thank Amy Van Hove for careful reading and editing of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Geckil H. Xu F. Zhang X. Moon S. Demirci U. Engineering hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2010;5:469. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu P. Takai K. Weaver V.M. Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:1. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruoslahti E. Yamaguchi Y. Proteoglycans as modulators of growth factor activities. Cell. 1991;64:867. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90308-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemler M.E. Integrin associated proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:578. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Discher D.E. Janmey P. Wang Y.L. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paluch E. Heisenberg C.P. Biology and physics of cell shape changes in development. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R790. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godfrey E.W. Gradall K.S. Basal lamina molecules are concentrated in myogenic regions of the mouse limb bud. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1998;198:481. doi: 10.1007/s004290050198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benoit D.S. Anseth K.S. The effect on osteoblast function of colocalized RGD and PHSRN epitopes on PEG surfaces. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5209. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benoit D.S. Schwartz M.P. Durney A.R. Anseth K.S. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Mater. 2008;7:816. doi: 10.1038/nmat2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang F. Williams C.G. Wang D.A. Lee H. Manson P.N. Elisseeff J. The effect of incorporating RGD adhesive peptide in polyethylene glycol diacrylate hydrogel on osteogenesis of bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5991. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mieszawska A.J. Kaplan D.L. Smart biomaterials—regulating cell behavior through signaling molecules. BMC Biol. 2010;8:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse J.R. Engler A.J. Stiffness gradients mimicking in vivo tissue variation regulate mesenchymal stem cell fate. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao H. Munoz-Pinto D. Qu X. Hou Y. Grunlan M.A. Hahn M.S. Influence of hydrogel mechanical properties and mesh size on vocal fold fibroblast extracellular matrix production and phenotype. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:1161. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunn J.W. Turner S.D. Mann B.K. Adhesive and mechanical properties of hydrogels influence neurite extension. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;72:91. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leach J.B. Brown X.Q. Jacot J.G. Dimilla P.A. Wong J.Y. Neurite outgrowth and branching of PC12 cells on very soft substrates sharply decreases below a threshold of substrate rigidity. J Neural Eng. 2007;4:26. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/4/2/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leipzig N.D. Shoichet M.S. The effect of substrate stiffness on adult neural stem cell behavior. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6867. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu J. Bioactive modification of poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4639. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin C.C. Anseth K.S. Cell-cell communication mimicry with poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for enhancing beta-cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014026108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez N. Schmidt C.E. Nerve growth factor-immobilized polypyrrole: bioactive electrically conducting polymer for enhanced neurite extension. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;81:135. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolodziej C.M. Kim S.H. Broyer R.M. Saxer S.S. Decker C.G. Maynard H.D. Combination of integrin-binding peptide and growth factor promotes cell adhesion on electron-beam-fabricated patterns. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:247. doi: 10.1021/ja205524x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alberti K. Davey R.E. Onishi K. George S. Salchert K. Seib F.P. Bornhauser M. Pompe T. Nagy A. Werner C. Zandstra P.W. Functional immobilization of signaling proteins enables control of stem cell fate. Nat Methods. 2008;5:645. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao J. Kim Y.M. Coe H. Zern B. Sheppard B. Wang Y. A neuroinductive biomaterial based on dopamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606237103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Z. Yu P. Geller H.M. Ober C.K. The role of hydrogels with tethered acetylcholine functionality on the adhesion and viability of hippocampal neurons and glial cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2473. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daley W.P. Peters S.B. Larsen M. Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:255. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettinger C.J. Langer R. Borenstein J.T. Engineering substrate topography at the micro- and nanoscale to control cell function. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5406. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dalby M.J. Yarwood S.J. Johnstone H.J. Affrossman S. Riehle M.O. Fibroblast signaling events in response to nanotopography: a gene array study. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci. 2002;1:12. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2002.806930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kustra S. Bettinger C.J. Smart polymers and interfaces for dynamic cell-biomaterial interactions. MRS Bulletin. 2012;37:836. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulte V.A. Diez M. Moller M. Lensen M.C. Topography-induced cell adhesion to Acr-sP(EO-stat-PO) hydrogels: the role of protein adsorption. Macromol Biosci. 2011;11:1378. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appelman T.P. Mizrahi J. Elisseeff J.H. Seliktar D. The influence of biological motifs and dynamic mechanical stimulation in hydrogel scaffold systems on the phenotype of chondrocytes. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1508. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei G. Jin Q. Giannobile W.V. Ma P.X. The enhancement of osteogenesis by nano-fibrous scaffolds incorporating rhBMP-7 nanospheres. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2087. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seliktar D. Designing cell-compatible hydrogels for biomedical applications. Science. 2012;336:1124. doi: 10.1126/science.1214804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeForest C.A. Anseth K.S. Advances in bioactive hydrogels to probe and direct cell fate. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2012;3:421. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-062011-080945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lieleg O. Ribbeck K. Biological hydrogels as selective diffusion barriers. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:543. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flory P.J. Principles of Polymer Chemistry. Ithaca: Cornell University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu S. Ramirez W.F. Anseth K.S. Photopolymerized, multilaminated matrix devices with optimized nonuniform initial concentration profiles to control drug release. J Pharm Sci. 2000;89:45. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6017(200001)89:1<45::AID-JPS5>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anseth K.S. Bowman C.N. Brannon-Peppas L. Mechanical properties of hydrogels and their experimental determination. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1647. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)87644-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bryant S.J. Anseth K.S. Hydrogel properties influence ECM production by chondrocytes photoencapsulated in poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:63. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu R. Boudreau A. Bissell M.J. Tissue architecture and function: dynamic reciprocity via extra- and intra-cellular matrices. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:167. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khatiwala C.B. Kim P.D. Peyton S.R. Putnam A.J. ECM compliance regulates osteogenesis by influencing MAPK signaling downstream of RhoA and ROCK. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:886. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ventre M. Causa F. Netti P.A. Determinants of cell-material crosstalk at the interface: towards engineering of cell instructive materials. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9:2017. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Massia S.P. Hubbell J.A. An RGD spacing of 440 nm is sufficient for integrin alpha V beta 3-mediated fibroblast spreading and 140 nm for focal contact and stress fiber formation. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:1089. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.5.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ge C. Xiao G. Jiang D. Franceschi R.T. Critical role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-MAPK pathway in osteoblast differentiation and skeletal development. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:709. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Discher D.E. Mooney D.J. Zandstra P.W. Growth factors, matrices, and forces combine and control stem cells. Science. 2009;324:1673. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelham R.J., Jr. Wang Y. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H.B. Dembo M. Wang Y.L. Substrate flexibility regulates growth and apoptosis of normal but not transformed cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1345. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engler A.J. Sen S. Sweeney H.L. Discher D.E. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Owen S.C. Shoichet M.S. Design of three-dimensional biomimetic scaffolds. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:1321. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tibbitt M.W. Anseth K.S. Hydrogels as extracellular matrix mimics for 3D cell culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2009;103:655. doi: 10.1002/bit.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutolf M.P. Materials science: Cell environments programmed with light. Nature. 2012;482:477. doi: 10.1038/482477a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Polizzotti B.D. Fairbanks B.D. Anseth K.S. Three-dimensional biochemical patterning of click-based composite hydrogels via thiolene photopolymerization. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1084. doi: 10.1021/bm7012636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zipfel W.R. Williams R.M. Webb W.W. Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:1369. doi: 10.1038/nbt899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tibbitt M.W. Kloxin A.M. Dyamenahalli K.U. Anseth K.S. Controlled two-photon photodegradation of PEG hydrogels to study and manipulate subcellular interactions on soft materials. Soft Matter. 2010;6:5100. doi: 10.1039/C0SM00174K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kloxin A.M. Kasko A.M. Salinas C.N. Anseth K.S. Photodegradable hydrogels for dynamic tuning of physical and chemical properties. Science. 2009;324:59. doi: 10.1126/science.1169494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guvendiren M. Burdick J.A. Stiffening hydrogels to probe short- and long-term cellular responses to dynamic mechanics. Nat Commun. 2012;3:792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeForest C.A. Anseth K.S. Cytocompatible click-based hydrogels with dynamically tunable properties through orthogonal photoconjugation and photocleavage reactions. Nat Chem. 2011;3:925. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khetan S. Burdick J.A. Patterning network structure to spatially control cellular remodeling and stem cell fate within 3-dimensional hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8228. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo Y. Shoichet M.S. A photolabile hydrogel for guided three-dimensional cell growth and migration. Nat Mater. 2004;3:249. doi: 10.1038/nmat1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frey M.T. Wang Y.L. A photo-modulatable material for probing cellular responses to substrate rigidity. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1918. doi: 10.1039/b818104g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramanan V.V. Katz J.S. Guvendiren M. Cohen E.R. Marklein R.A. Burdick J.A. Photocleavable side groups to spatially alter hydrogel properties and cellular interactions. J Mat Chem. 2010;20:8920. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kloxin A.M. Benton J.A. Anseth K.S. In situ elasticity modulation with dynamic substrates to direct cell phenotype. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fairbanks B.D. Singh S.P. Bowman C.N. Anseth K.S. Photodegradable, photoadaptable hydrogels via radical-mediated disulfide fragmentation reaction. Macromolecules. 2011;44:2444. doi: 10.1021/ma200202w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Connelly J.T. Petrie T.A. Garcia A.J. Levenston M.E. Fibronectin- and collagen-mimetic ligands regulate bone marrow stromal cell chondrogenesis in three-dimensional hydrogels. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;22:168. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v022a13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bellamkonda R. Ranieri J.P. Aebischer P. Laminin oligopeptide derivatized agarose gels allow three-dimensional neurite extension in vitro. J Neurosci Res. 1995;41:501. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu X. Dillon G.P. Bellamkonda R.B. A laminin and nerve growth factor-laden three-dimensional scaffold for enhanced neurite extension. Tissue Eng. 1999;5:291. doi: 10.1089/ten.1999.5.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lin-Gibson S. Bencherif S. Cooper J.A. Wetzel S.J. Antonucci J.M. Vogel B.M. Horkay F. Washburn N.R. Synthesis and characterization of PEG dimethacrylates and their hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:1280. doi: 10.1021/bm0498777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fairbanks B.D. Schwartz M.P. Halevi A.E. Nuttelman C.R. Bowman C.N. Anseth K.S. A versatile synthetic extracellular matrix mimic via thiol-norbornene photopolymerization. Adv Mater. 2009;21:5005. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salinas C.N. Anseth K.S. Mixed mode thiol-acrylate photopolymerizations for the synthesis of PEG-peptide hydrogels. Macromolecules. 2008;41:6019. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lin C.C. Anseth K.S. PEG hydrogels for the controlled release of biomolecules in regenerative medicine. Pharm Res. 2009;26:631. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9801-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Georges P.C. Janmey P.A. Cell type-specific response to growth on soft materials. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1547. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01121.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ferrier J. Ross S.M. Kanehisa J. Aubin J.E. Osteoclasts and osteoblasts migrate in opposite directions in response to a constant electrical field. J Cell Physiol. 1986;129:283. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041290303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Udina E. Furey M. Busch S. Silver J. Gordon T. Fouad K. Electrical stimulation of intact peripheral sensory axons in rats promotes outgrowth of their central projections. Exp Neurol. 2008;210:238. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McClellan A.D. Kovalenko M.O. Benes J.A. Schulz D.J. Spinal cord injury induces changes in electrophysiological properties and ion channel expression of reticulospinal neurons in larval lamprey. J Neurosci. 2008;28:650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3840-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee T.H. Pan H. Kim I.S. Kim J.K. Cho T.H. Oh J.H. Yoon Y.B. Lee J.H. Hwang S.J. Kim S.J. Functional regeneration of a severed peripheral nerve with a 7-mm gap in rats through the use of an implantable electrical stimulator and a conduit electrode with collagen coating. Neuromodulation. 2010;13:299. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2010.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guan J. Wang F. Li Z. Chen J. Guo X. Liao J. Moldovan N.I. The stimulation of the cardiac differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in tissue constructs that mimic myocardium structure and biomechanics. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5568. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Runge M.B. Dadsetan M. Baltrusaitis J. Knight A.M. Ruesink T. Lazcano E.A. Lu L. Windebank A.J. Yaszemski M.J. The development of electrically conductive polycaprolactone fumarate-polypyrrole composite materials for nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5916. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moroder P. Runge M.B. Wang H. Ruesink T. Lu L. Spinner R.J. Windebank A.J. Yaszemski M.J. Material properties and electrical stimulation regimens of polycaprolactone fumarate-polypyrrole scaffolds as potential conductive nerve conduits. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:944. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Park J.S. Park K. Moon H.T. Woo D.G. Yang H.N. Park K.H. Electrical pulsed stimulation of surfaces homogeneously coated with gold nanoparticles to induce neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells. Langmuir. 2009;25:451. doi: 10.1021/la8025683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vivo M. Puigdemasa A. Casals L. Asensio E. Udina E. Navarro X. Immediate electrical stimulation enhances regeneration and reinnervation and modulates spinal plastic changes after sciatic nerve injury and repair. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:180. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Graves M.S. Hassell T. Beier B.L. Albors G.O. Irazoqui P.P. Electrically mediated neuronal guidance with applied alternating current electric fields. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:1759. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Manthorpe M. Engvall E. Ruoslahti E. Longo F.M. Davis G.E. Varon S. Laminin promotes neuritic regeneration from cultured peripheral and central neurons. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:1882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.6.1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kotwal A. Schmidt C.E. Electrical stimulation alters protein adsorption and nerve cell interactions with electrically conducting biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2001;22:1055. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weaver J.C. Astumian R.D. The response of living cells to very weak electric fields: the thermal noise limit. Science. 1990;247:459. doi: 10.1126/science.2300806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bendrea A.D. Cianga L. Cianga I. Review paper: progress in the field of conducting polymers for tissue engineering applications. J Biomater Appl. 2011;26:3. doi: 10.1177/0885328211402704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Guiseppi-Elie A. Electroconductive hydrogels: synthesis, characterization and biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2701. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu X. Gilmore K.J. Moulton S.E. Wallace G.G. Electrical stimulation promotes nerve cell differentiation on polypyrrole/poly (2-methoxy-5 aniline sulfonic acid) composites. J Neural Eng. 2009;6:065002. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/6/065002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khang D. Park G.E. Webster T.J. Enhanced chondrocyte densities on carbon nanotube composites: the combined role of nanosurface roughness and electrical stimulation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;86:253. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Woo D.G. Shim M.S. Park J.S. Yang H.N. Lee D.R. Park K.H. The effect of electrical stimulation on the differentiation of hESCs adhered onto fibronectin-coated gold nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5631. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Khang D. Kim S.Y. Liu-Snyder P. Palmore G.T. Durbin S.M. Webster T.J. Enhanced fibronectin adsorption on carbon nanotube/poly(carbonate) urethane: independent role of surface nano-roughness and associated surface energy. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4756. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ciofani G. Danti S. D'Alessandro D. Ricotti L. Moscato S. Bertoni G. Falqui A. Berrettini S. Petrini M. Mattoli V. Menciassi A. Enhancement of neurite outgrowth in neuronal-like cells following boron nitride nanotube-mediated stimulation. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6267. doi: 10.1021/nn101985a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen Y.H. Chung Y.C. Wang I.J. Young T.H. Control of cell attachment on pH-responsive chitosan surface by precise adjustment of medium pH. Biomaterials. 2012;33:1336. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Guillaume-Gentil O. Semenov O.V. Zisch A.H. Zimmermann R. Voros J. Ehrbar M. pH-controlled recovery of placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cell sheets. Biomaterials. 2011;32:4376. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berger J. Reist M. Mayer J.M. Felt O. Gurny R. Structure and interactions in chitosan hydrogels formed by complexation or aggregation for biomedical applications. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2004;57:35. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(03)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yeh H.Y. Lin J.C. Surface characterization and in vitro platelet compatibility study of surface sulfonated chitosan membrane with amino group protection-deprotection strategy. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2008;19:291. doi: 10.1163/156856208783720985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tooney N.M. Mosesson M.W. Amrani D.L. Hainfeld J.F. Wall J.S. Solution and surface effects on plasma fibronectin structure. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:1686. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.6.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yang J. Yamato M. Shimizu T. Sekine H. Ohashi K. Kanzaki M. Ohki T. Nishida K. Okano T. Reconstruction of functional tissues with cell sheet engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5033. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Isenberg B.C. Tsuda Y. Williams C. Shimizu T. Yamato M. Okano T. Wong J.Y. A thermoresponsive, microtextured substrate for cell sheet engineering with defined structural organization. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2565. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kong B. Choi J.S. Jeon S. Choi I.S. The control of cell adhesion and detachment on thin films of thermoresponsive poly[(N-isopropylacrylamide)-r-((3-(methacryloylamino)propyl)-dimethyl(3-sulfopro pyl)ammonium hydroxide)] Biomaterials. 2009;30:5514. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Patel N.G. Cavicchia J.P. Zhang G. Zhang Newby B.M. Rapid cell sheet detachment using spin-coated pNIPAAm films retained on surfaces by an aminopropyltriethoxysilane network. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:2559. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schmaljohann D. Oswald J. Jorgensen B. Nitschke M. Beyerlein D. Werner C. Thermo-responsive PNiPAAm-g-PEG films for controlled cell detachment. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1733. doi: 10.1021/bm034160p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kikuchi A. Okano T. Pulsatile drug release control using hydrogels. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54:53. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kumashiro Y. Yamato M. Okano T. Cell attachment-detachment control on temperature-responsive thin surfaces for novel tissue engineering. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:1977. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]