Abstract

Recent advances in the fields of microfabrication, biomaterials, and tissue engineering have provided new opportunities for developing biomimetic and functional tissues with potential applications in disease modeling, drug discovery, and replacing damaged tissues. An intact epithelium plays an indispensable role in the functionality of several organs such as the trachea, esophagus, and cornea. Furthermore, the integrity of the epithelial barrier and its degree of differentiation would define the level of success in tissue engineering of other organs such as the bladder and the skin. In this review, we focus on the challenges and requirements associated with engineering of epithelial layers in different tissues. Functional epithelial layers can be achieved by methods such as cell sheets, cell homing, and in situ epithelialization. However, for organs composed of several tissues, other important factors such as (1) in vivo epithelial cell migration, (2) multicell-type differentiation within the epithelium, and (3) epithelial cell interactions with the underlying mesenchymal cells should also be considered. Recent successful clinical trials in tissue engineering of the trachea have highlighted the importance of a functional epithelium for long-term success and survival of tissue replacements. Hence, using the trachea as a model tissue in clinical use, we describe the optimal structure of an artificial epithelium as well as challenges of obtaining a fully functional epithelium in macroscale. One of the possible remedies to address such challenges is the use of bottom-up fabrication methods to obtain a functional epithelium. Modular approaches for the generation of functional epithelial layers are reviewed and other emerging applications of microscale epithelial tissue models for studying epithelial/mesenchymal interactions in healthy and diseased (e.g., cancer) tissues are described. These models can elucidate the epithelial/mesenchymal tissue interactions at the microscale and provide the necessary tools for the next generation of multicellular engineered tissues and organ-on-a-chip systems.

Introduction

One of the key challenges in tissue engineering is reproducing the complex interactions of different cell types that are necessary to obtain a functional tissue. Compared to other tissue types (e.g., connective, nerve, and muscle tissue) the epithelium is relatively easy to maintain in vitro at a close biological state to that of in vivo. However, achieving this in multicellular engineered tissues, where large areas need to be covered and the underlying substrate is under constant remodeling, is not as straightforward. This review describes the necessity of a functional epithelial layer in tissue engineering and efforts that have been made for the development of an artificial epithelium. In addition, the interaction between epithelial cells, the basement membrane (BM), and the underlying mesenchymal tissue that are important determinants of epithelial cell health and integrity are discussed. Finally, we discuss the design of microscale epithelial tissue models for drug testing, disease models, and basic research.

Nearly all tissues contain an epithelial layer. Hence, the development of the epithelial layer is critical to enhance integrity and functionality of implants and artificial tissues. The lack of a functional epithelium could cause long-term problems such as restenosis in the case of stents1 or peri-implantitis and loosening in the case of dental implants.2 In addition, impaired epithelium function has been implicated as the cause of some widespread and severe diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, for which, availability of an engineered, functional epithelium might be a remedy.3 Thus, it is important to obtain a functional epithelial layer in the context of engineered multicellular tissues.

One of the main functions of epithelial cells is the formation of a barrier that protects the body against various physical, chemical, and microbial insults. Epithelial tissue covers all body surfaces and cavities. In hollow organs, they form the inner lining of the organs and collectively they play a key role in maintaining the homeostasis of the body. Epithelial tissue's diverse structural and functional properties depend on its location.4 In organs with direct contact with the external environment such as the cornea, respiratory tract, skin, and digestive system, specialized epithelial cells maintain the equilibrium between the body and the surroundings. The epithelial layer can also help the innate immune system as it is generally the first line of defense against pathogens or invasive organisms and triggers the events that start adaptive immune responses.5 The importance of the epithelial layer can be further highlighted by many diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, where dysfunctional epithelium causes significant inflammatory symptoms. Epithelium tissues have a high renewal capacity, due to the presence of resident stem cells. However, in the case of deep injuries such as extensive burns and subsequent persistent infection due to loss of skin barrier function, a limit is reached where the epithelium self-healing cannot occur.6,7 This effect leads to a significant loss of tissue function and might also act as a facilitating factor for other problems such as infection.

Tissue engineered epithelium has become a viable option for the treatment of deep injuries. However, the success rate is not the same for all tissues, since the behavior of epithelial cells varies significantly between different organs. For example, epithelialization of polymer-based implants without any prior cell seeding has been reported in bladder replacement.8 However, a similar coverage has not been demonstrated for regeneration of the trachea.9

There are two modes of epithelial renewal,10 that can happen simultaneously, depending on the nature and location of the injury: (1) a constant renewal mode such as in intestine and (2) renewal via activation of semiquiescent cells by dedifferentiation upon injury such as in bladder. Given all these diversities, it is important to develop specific solutions for the formation of the epithelial layer for each target organ and take into account the in vivo characteristics of epithelial cells.

Epithelial Structures

The characteristics of the epithelium include (1) polarization of the cells, (2) contact with the BM, and (3) limited intercellular space for effective barrier function.11 Different types of epithelium that are found in several organs are listed in Table 1. The functions of the epithelium are diverse and range from barrier function and physical removal of particles to cytokine and chemokine production in glands, all of which should be considered as part of the design of artificial tissues and organs to enable full functionality.12

Table 1.

| Type | Structure | Location |

|---|---|---|

| Stratified squamous epithelium | Several layers of epithelial cells, protective cells | Skin (Keratinized) Cornea, Esophagus |

| Columnar epithelium | Single-layer cells, mainly secretory functions | Intestine, Stomach |

| Pseudostratified | A thick layer with a stratified appearance, but all cells contact the basement membrane | Trachea |

| Simple squamous | Single- and well-spread cell layer | Lung, Endothelium |

| Cuboidal | Cell aspects are equal, main function is to retain liquids | Ducts, Glands |

| Transitional | Specific to the urinary system, the variation depends on the distension (from 5—layers to 2–3 under distension) | Urothelium |

Epithelial layer structure in different organs

Epithelial tissues are predominantly composed of cells and contain relatively little extracellular matrix (ECM). Epithelial tissues, which are in contact with the external environment, have distinctly different cellular organizations according to their function. When the main function of the epithelial layer is coverage, it is in the form of a continuous sheet of cells, in which the number of layers and their thickness depend on the tissue type. For example, in skin, the epithelial layer, epidermis, is highly keratinized comprising of five layers, where the fifth layer or strata germinativium provides the cells for the regeneration of other layers.14 On the other hand, the cornea is composed of the nonkeratinized, stratified epithelium, which is continuously renewed. In the esophagus, the epithelium serves as a protective layer against the mechanical damages that can be inflicted by the passage of food during digestion.15 Structurally, the esophagus epithelium is a stratified, squamous epithelium. Oral mucosa, which is divided to masticatory mucosa, specialized mucosa, and lining mucosa, has two layers: a stratified, thick squamous epithelial layer and lamina propria, which is a woven, vascularized network of the ECM populated by the progenitor cells and the fibroblasts.

In some tissues, the presence of cilia, an organelle in the form of hair-like extension, on the luminal surface of the epithelial cells is necessary. For example, the epithelial layer of the trachea is mainly composed of ciliated epithelial cells in a pseudostratified structure together with a smaller number of goblet and basal cells. Basal cells have the capacity to proliferate and differentiate into other cell types for barrier renewal.16 The goblet cells are secretory cells that produce mucins, which are complex glycoproteins. Mucins are the main component of mucus and are responsible for the capture of particles and pathogens. Among the 20 different types of human mucins identified to date, MUC5AC and MUC5B are most abundant in airways.17 Their action facilitates the removal of the encapsulated particles, which enables their removal by the ciliary cells. It is therefore beneficial that an artificial respiratory epithelium possesses the ciliary, the goblet, and a layer of basal cells to ensure optimal function and future renewal.

The epithelial cells interact with the surrounding tissues either via cell–cell contacts or through the ECM. For example, the intestinal epithelium by itself is a simple columnar epithelium, where the cells are bound by tight junctions. The turnover time of the epithelial cells facing the intestinal content is 4–5 days. This renewal is achieved by the stem cell reserves that commit to three of the possible lineages with specific functions: namely, enteroendocrine (secretion of hormones with respect to the luminal content), absorptive, and muco-secreting (goblet).18 Goblet cells secrete mucus, which primarily acts as a lubricant. Absorptive epithelial cells have microvilli, extrusions on epithelial cells with a diameter of approximately 100 nm that create the brush border, which is in contact with the intestinal contents and increases the surface area necessary for nutrient absorption. Aside from this heterogeneity, interactions with several cell types, including myofibroblasts and immune cells, are essential for full functionality of the intestinal epithelium. For example, intestinal epithelium's interaction with mast cells is an important part of host defense against pathogens. Furthermore, intestinal myofibroblasts, are located beneath the BM and have the capacity to mediate the flow of information between the intestinal epithelium and the underlying tissue through the production of cytokines and cell–cell contact. They also secrete ECM components and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which play an important role in wound healing.19

Pathologies related to epithelial tissues

Tissue replacement may be required due to various epithelial pathologies in a range of diseases from physical damage (e.g., corneal scars), infections, and burns to more serious conditions such as inflammatory diseases and cancers.

The only remedy in many cases of hollow organ cancers, such as the trachea, esophagus, or colon cancers, is the resection of the tumor. In some cases, where the resected part is small enough, functionality can be maintained or restored with end–end anastomosis. However, beyond a certain size, it is necessary to replace the tissue. Furthermore, long-term exposure of the epithelium to nonphysiological conditions results in pathologies that can severely affect organ functionality. For example, Barrett's esophagus is a common disease related to the mucosal layer where the squamous epithelium is replaced by a metaplastic glandular epithelium mainly due to reflux and excessive presence of gastric acid in the esophagus. Barrett's esophagus increases the risk of cancer significantly, and it may lead to tumor formation and subsequent removal of tissue in many cases requires tissue replacement.

Many other devastating diseases are associated with the epithelium. Cystic fibrosis and ciliary dyskinesia are examples of pulmonary diseases, where epithelial layer dysfunction plays an important role in pathogenesis. Especially in the late stages of cystic fibrosis, lung transplantation might be the only option. Moreover, other problems such as leakage, infection, and restenosis are also related to the absence of a functional epithelium.

An important aspect of developing epithelial tissue is to maintain the proper ratio of different cell types; otherwise, the engineered structures behave in a way similar to disease states. For example, in asthma, the epithelium layer shows aberrant formations such as goblet metaplasia, which results in recruitment of fibroblasts and formation of subepithelial fibrosis. This phenomenon results in narrowing of the lumen and airway obstruction in the long run.20 A high number of goblet cells in an epithelial construct might have a similar effect in vivo. The challenges common to many tissue engineering projects include the loss of epithelial cell phenotypes such as loss of ciliary action, suboptimal secretory functions, and slow renewal. For example, in the case of oral mucosa, low self-renewing capacity of the transplanted epithelial cells can cause problems such as oral function interference and a higher risk of infection due to compromised lining of the cavity.21 These issues may also arise from the loss of basal cells during the culture period. Another critical issue for epithelium regeneration is the control of cell polarization to ensure mimicking the morphology of the epithelium.22 The utilization of BM mimicking systems is a key factor in achieving polarity. In addition to polarity, controlling the migration of epithelial cells with physical and biochemical gradients is critical for preventing discontinuities.23 Therefore, in tissue engineered constructs, it is crucial to provide surfaces that are favorable for the migration and basal-apical polarization of epithelial cells.

Methods to Control Epithelial Cell Behavior in Tissue Engineering

Mimicking BM structure

All epithelial tissues are in contact with an underlying BM. This thin ECM structure (∼100 nm) is mainly composed of collagen type IV, laminin, glycoproteins such as nidogen and perlecan (a glycosaminoglycan that contains high amount of heparan sulfate). The presence of other minor components such as collagen type XV, XVIII, SPARC (secreted protein, acidic and rich in cysteine), fibulin, and their relative quantities define the properties of a specific BM. Physically, BM is a nanofibrillar structure secreted by the epithelial cells and the underlying mesenchymal cells.24 Collagen type IV is the main constituent of the BM, which consists of three α-chains that are divided into the following three domains: N-terminal 7S collagenous domain, a triple-helix domain, and a C-Terminal noncollagenous (NC1) domain. The self-assembled suprastructures of collagen type IV (a network linked to the laminin via other BM components) and laminin (honeycombs) give the BM its mesh-like structure. The function of epithelial cells is affected by the BM structures in a significant manner. Thus, for directing the epithelial cell behavior, the key factor is mimicking the BM construct. A wide range of techniques such as electrospinning, spray deposition, self-assembly, polyelectrolyte multilayer methodologies, and a decellularized ECM have been used to fabricate structures that mimic BM based on natural and synthetic polymers.25–29

In each organ, a tissue-specific ECM regulates the functionality of epithelial cells. These epithelial cell/ECM interactions need to be replicated for the regeneration of the tissue. Therefore, mimicking the physical and biological properties of BM is critical for achieving fully differentiated epithelial layers.30 To this end, the amniotic membrane has been widely used either by itself or in combination with cells. For the corneal epithelium, replacements in humans therapies based on transfer of limbal epithelial cells on amniotic membranes were more successful than using neat amniotic membrane.31 Both chemical composition and the physical properties of the BM have significant impacts on the behavior of epithelial cells. For example, the corneal epithelium's basal membrane is composed of nanofibrillar collagen meshes with nanometer-scale pores. It was observed that the epithelial cells proliferate less on highly fibrillar structures, especially when the fibers are closer to microscale.32 Qualitative analyses confirmed that the attachment of epithelial cells to synthetic surfaces can be challenging.33 Thus, for culturing epithelial cells on surfaces that do not contain BM components such as poly (L-lactic acid)34 or chitosan/gelatin hydrogels,35 it is critical to mimic the physical characteristics of BM to promote cell attachment and migration. Recent studies have demonstrated that the addition of components such as elastin-like peptides onto the surface of nanofibrous collagen scaffolds can significantly propagate the epithelial cell proliferation in oral mucosa models.36 Providing a biomimetic BM structure can also be used to direct epithelial cell migration in vivo when the coverage of large surface areas is necessary.27

Controlling epithelial cell migration

The topographical structure of epithelial cells on a surface is regulated by the interaction of cells with the BM and other cells (Fig. 1). On average, epithelial cells settle in a hexagonal shape, which is generally defined as the “cobblestone pattern” in the literature.37 Given the importance of cell–cell contacts in the epithelial tissue structure,38 biomaterial surfaces with the biomimetic, nanofibrillar topographies can facilitate the formation of the functional epithelium.

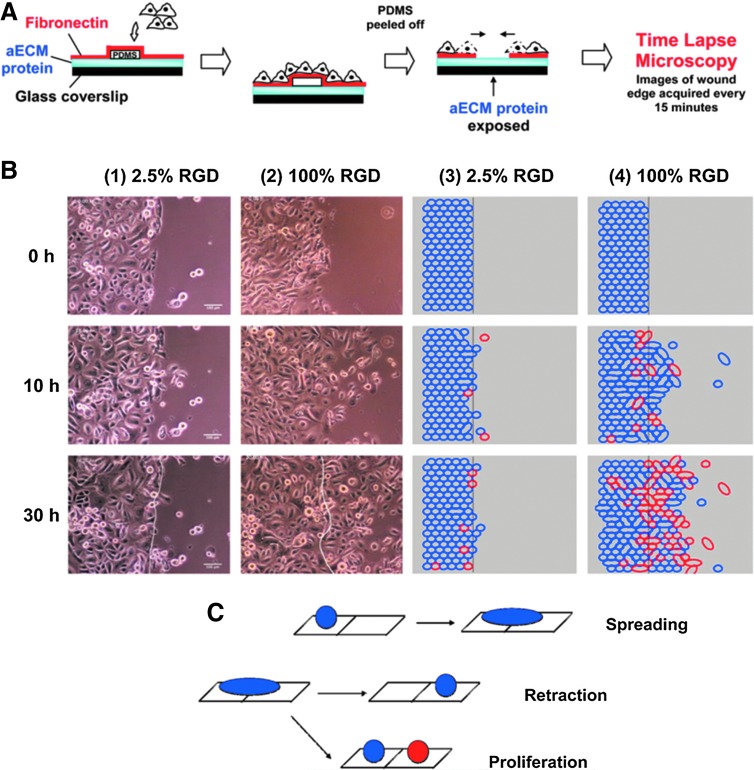

FIG. 1.

The effect of substrate properties on epithelial cell migration. The decision-making process of corneal epithelial cells about migration is governed by the amount of available RGD moieties in vitro, as a model of in vivo migration during wound healing. (A) Formation of a wound model with different levels of RGD coating. (B) Time-lapse microscopy tracking of the migration of individual epithelial cells for 30 h showed that the difference in RGD availability significantly affected the boundary crossing decision by the epithelial cells. (C) Possible modes of boundary crossing by epithelial cells.45 PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

In vivo studies have shown that the initial coverage of an injured area of the epithelium is based on cell migration rather than cell proliferation. The epithelial/ECM interaction is crucial for dedifferentiation and redifferentiation of the epithelial cells and in combination with degradation of the BM structures, they are implicated in epithelial migration.39 B-1 subunit integrins contribute to the migration of epithelial cells on laminin and collagen type IV.40 However, in large wounds, the cells' ability to migrate may not be sufficient to cover the entire wound area.

Degradation of the cellular microenvironment by MMPs is an important aspect of epithelial regeneration as it renders it more amenable to remodeling by cells. Harnessing these events and planning the actual outcomes of the degradation of scaffolds by MMPs can direct the implanted material toward integration and regeneration rather than scar formation or rejection. In particular, secretion of MMP 3, 7, 9, and 11 are important in facilitating cell migration.41 MMP secretion by other cells can also affect epithelial cell behavior. For example, MMP 12, which is secreted by macrophages during acute lung injury, is implicated in chronic inflammation of epithelial tissues.42 It has also been demonstrated that the overexpression of MMP 14 can be used by migrating epithelial cells and the difference in the motility of the cells can lead to their reorganization. For example, data obtained using a mammary duct model have shown that the highest expression of MMP 14 was found in the cells at the end of the tubules, due to directional persistence.43 The rate of epithelial migration can also be controlled by the substrate as shown in a number of in vitro experiments with corneal epithelial cells on artificial ECM molecules and patterned surfaces.44,45 Studies show that the decision of boundary crossing by the epithelial cells is the main factor in the faster wound closure rather than the pure increase in the migration rate.39

The significance of the rate of migration is demonstrated clearly in bladder reconstruction.46 It has been shown that the urothelial coverage of the damaged area might take up to 2 weeks. The absence of epithelium during this period can cause events that lead to contracture.47 The epithelialization of implanted surfaces depends on cell migration; therefore, in the absence of in vitro epithelialization, it is crucial to control the speed of cell migration in vivo.

Effect of heterotypic interactions on epithelial cells

In general, a heterotypic interaction between cells is an important facilitator of desirable organ development.48,49 An example of these interactions that can be exploited in vitro is the vascular endothelial cell/osteoblast coculture system in a variety of scaffolds, which are shown to induce endothelial cells to form capillary sprouts.50,51 A similar approach has been used in the vascularization of the epithelium.52

In the case of the epithelium, the interactions between the mesenchymal and epithelial cells are essential for tissue function in most organs. For example, sequential and reciprocal interactions between the stem cells and the epithelial cells are required for tooth development. It has also been shown that the presence of the BM can affect the differentiation of stem cells into odontoblasts.53,54 In addition, the dermal papilla and dermal sheath cells induce the differentiation of keratinocytes into hair follicles.55 Furthermore, the variation of the underlying fibroblast cells alter the phenotype of the respiratory epithelium between the proximal alveolar or distal tracheal phenotypes.56 The presence of stem cells in tracheal grafts in fetal tissues also result in full epithelialization of the grafts, whereas plain grafts fail to have an epithelial layer upon birth.57

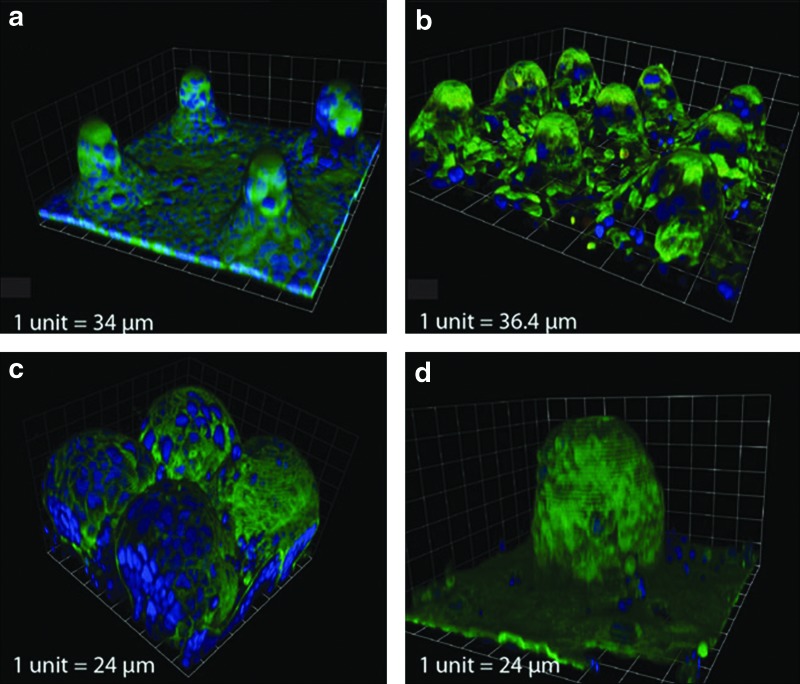

Miscommunication between the stromal layer and the epithelial layer has been observed in many diseases such as fibrosis and cancer. This phenomenon is also observed by in vitro coculturing of bronchial epithelial cells with normal and cancerous fibroblasts. When normal fibroblasts are present, the differentiation of epithelium is facilitated, whereas the presence of cancer cells causes the epithelium to migrate into the collagen gel used as the substrate and to form nodules and cysts.56 Similar observations have been made with esophageal models, where epithelial cell lines are used and a hyper-proliferative epithelium is induced58 (Fig. 2).

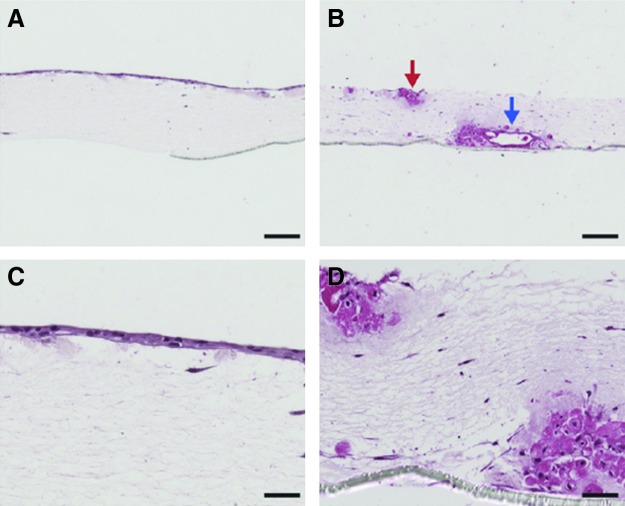

FIG. 2.

Effect of the mesenchymal cells on epithelium. In the presence of normal lung fibroblasts, bronchial epithelial cells form a confluent layer (A, C), whereas in the presence of cancer-associated fibroblasts, they formed invaginations and do not form a continuous layer (denoted by arrows) (B, D).56 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

The isolated cells from epithelial layers are a mixture of differentiated cells, proliferating cells, and stem cells. This diversity is lost under standard culture conditions, which can be prevented by coculture systems that provide a more biomimetic environment.59 For example, the presence of corneal fibroblasts is important for the health of the epithelial layer.60 In vivo studies have demonstrated that transfer of respiratory epithelial cells to preformed fibrous capsules via fibrin glue improved their proliferation and differentiation. In fact, a fully differentiated, pseudostratified epithelium was produced, which was unlikely to be achieved by epithelial cell cultures alone.61

Epithelium in Clinical Tissue-Engineering Applications

Epithelial grafts and in-situ epithelialization

Epithelial grafts are one of the most successful developments in regenerative medicine. The ability of epithelial cells to differentiate and take over the functionalities of the target area facilitates autologous transplants. This is best exemplified by the feasibility of grafting buccal, skin, or bowel epithelial layers for urinary tract rehabilitation.62 However, the success of the grafting approach depends on other factors rather than just the extent in which the epithelium is interchangeable. Other problems include donor-site morbidity and slow dedifferentiation, which can create undesirable problems such as keratinization or excessive mucus formation.63 For example, utilization of skin grafts for respiratory system entails the risk of hair growth, mucus stagnation, and desquamation. Skin grafts are also used for oral mucosa, which may end up in hair formation inside the oral cavity or excessive keratinization of the grafted skin epithelium. Thus, application of differentiated epithelium specific to the target organ is always a safer approach.

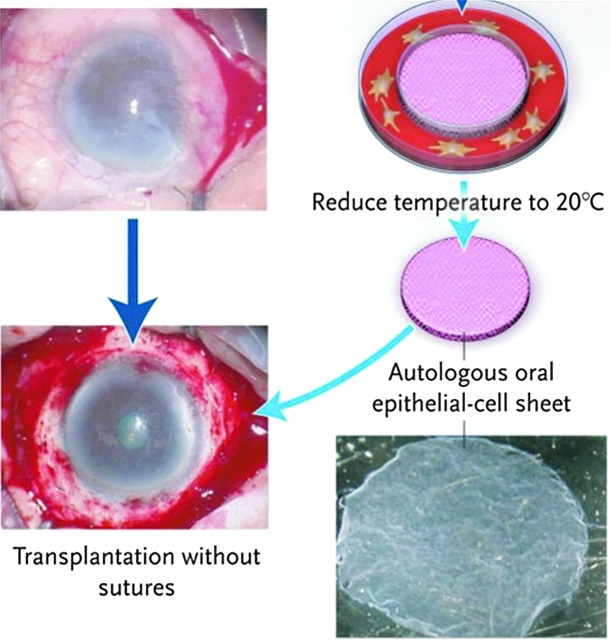

Cell sheet engineering shown in Figure 3 is a breakthrough in all epithelial layer-based tissue engineering applications.64 The engineered autologous cell sheets can not only be used in clinical settings, but they can also be transferred to implant surfaces as epithelium for tissue replacement.65 However, a major disadvantage of the cell sheet methodology is the time-consuming procedure to create a robust structure for transplantation and the difficulties in handling the sheets.66

FIG. 3.

Sutureless transfer of an autologous human epithelial cell sheet obtained from oral epithelial cells to a corneal scar after removal of the cell sheet from the thermoresponsive poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-pNIPAAM surface.66 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Grafting is not a viable treatment for large surface areas as it is difficult to cover the wound or damaged epithelia rapidly in vivo. The preseeded structures may not be the answer to this problem since the rate of supply of nutrients by the host cannot be established fast enough to feed the whole layer. Thus, the problems associated with the absence of epithelium, such as leakage, needs to be handled in different ways during the initial phases after implantation. This is particularly important in the urinary tract as the leakage of urine in the absence of urothelium could damage the surrounding tissues. Therefore, it is important to have a reliable source of epithelialization, such as epithelial cells on carriers.61 Control of implant fate via small regulatory interventions may be a necessity in the long run for all tissue-engineering products.67 As a remedy, in situ application of growth factor cocktails has been suggested to boost epithelialization in a number of recent studies.67 The significant role of a growth factor-rich microenvironment on epithelialization was evident in fetal tracheal replacement trials, where the epithelialization of the engineered cartilage by using amniocytes was rapid and complete in newborn lambs.68 However, conducting such proof-of-concept studies in this area is not easy and may face regulatory obstacles. This matter would be especially the case when the engineered tissue is implanted after a cancer resection, since the implantation of a regenerating tissue next to a newly resected tumor is a safety concern.69

Another aspect of epithelial grafting, which can cause problems is transdifferentiation, which is the differentiation of epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells. Although this type of differentiation is central during embryogenesis and also implicated in airway injury repair,70 given the possibility of transdifferentiation during cancer metastasis, its occurrence during therapeutic utilization is considered a risk.71 However, this transition may eventually be used for obtaining a steady source of epithelial stem cells.72 For better understanding of these events, artificial ECM structures are valuable tools to improve the control over the epithelial cell microenvironment.73

Transplantation of autologous and engineered epithelial layers for replacement of a defective site is considered as an effective strategy. However, when whole layers of a tissue or an organ need to be replaced, the task becomes more complex. In such cases, including full corneal, tracheal, and esophageal replacement, developing a functional epithelium is an integral yet technically challenging part of tissue-engineering and regenerative medicine approaches. The significance of all these considerations can be seen in the case of an artificial trachea. A tissue engineered trachea is on the verge of regular clinical trials and it is a good demonstration for the necessity of the epithelial layer.74

Epithelium in clinical full organ/multicellular tissue-engineering applications

The absence of a functional epithelial layer is one of the major issues in clinical applications of tissue engineering. For example, immediately after the implantation of a decellularized aorta for the replacement of a human bronchus, there is a risk of bacterial colonization due to the absence of an intact epithelium. After 1 year, an intact right bronchus was observed with progressive development of epithelium in the lumen (Fig. 4). The formation of an epithelial layer before implantation can be used to substantially increase the success rate of this operation. When an injury occurs, the specific steps of epithelial regeneration include dedifferentiation, migration, proliferation, and redifferentiation. The process may require a long period that can be affected by the topography of the injured area. For example, it was observed that the epithelial cells formed invaginations on the denuded surface of rat trachea and only after 5 weeks, a differentiated epithelium covered the denuded surface.75 Thus, the incorporation of epithelial cells in airway tissue engineering is a necessity.

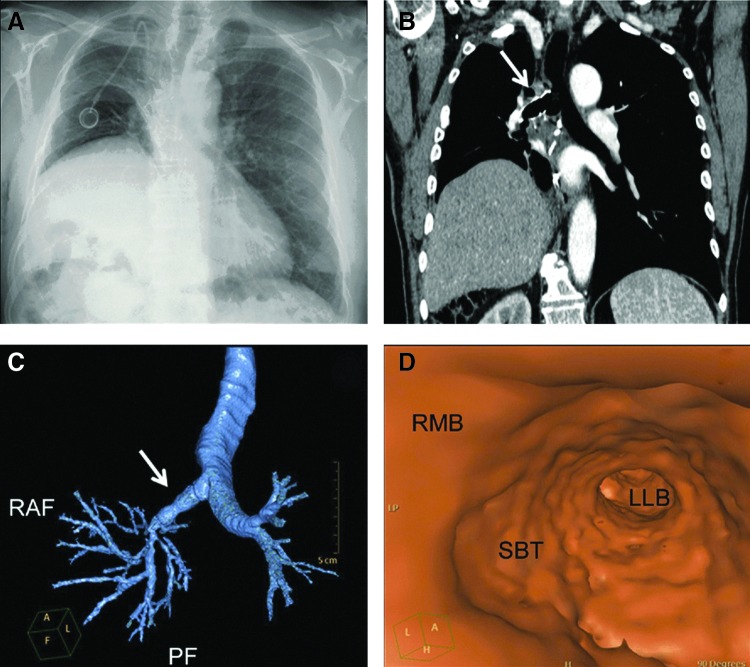

FIG. 4.

(A–D) Replacement of bronchi with decellularized aorta (denoted by arrows) following tissue resection due to bronchial cancer. (A) Chest X-Ray shows the re-expanded right lung after 6 months following implantation. (B, C) CT scans of the replaced bronchus (right) showed the patency of the implant with the bronchial tree. (D) Virtual CT scan for demonstration of the patency of the right main bronchus. RMB, right main bronchus; SBT, stented bronchial transplant; LLB, lower lobe bronchus.89 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Tissue engineered skin is one of the most established regenerative medicine solutions with a long clinical application record.76,77 Clinical trials have also been carried out for many other tissue types.78,79 For example, autologous buccal mucosa in conjunction with a decellularized dermal tissue have been used for reconstruction of urethra, where patients had functional urethra in a 36-month follow-up.80 Moreover, a functional bladder has been constructed using autologous urothelium without any adverse effects.81 Clinical replacement of oral mucosa with tissue engineered grafts resulted in fully differentiated, functional oral mucosa in a 6-month interval.82 For other organs, such as the liver, there are also tissue engineered constructs that are at the clinical trials.83

Epithelium in clinical trachea tissue engineering

The trachea is one of the organs, where the presence of an intact epithelium is crucial for its function and the development of an epithelial layer in tissue engineered tracheas is one of the cornerstones for its clinical success. Trachea is the passageway between the larynx and bronchi. It is composed of C-ring cartilages and an inner layer of pseudostratified, ciliary epithelium, which removes particles and microorganisms via mucociliary action. Tracheal defects stem from conditions such as cancer, chemical and physical injuries, and also congenital defects. Fatal congenital diseases, such as laryngotracheal agenesis, are also problems where regenerative medicine approaches are highly sought, especially due to the difficulties involved with fetal surgeries.84 In some cases, such defects can be resolved by end to end anastomosis if the length of the defect is less than 5 cm.85 However, when the size of the defect is larger than this limit, the implants or the tissue engineered structures become a necessity. To this end, allografts and a wide range of biomaterials have been used for replacing tracheal defects.9,86,87 The general problems associated with these kinds of implants are restenosis, collapse of the airway due to mechanical instability, and the problems associated with the lack of functional epithelium, which leads to infections and also facilitates restenosis.88 When the implant is not strong enough, airway collapse is the major issue. In models with decellularized systems, it has been shown that the presence of both chondrocytes and epithelial cells are essential for long-term survival in pigs.87

The methods used in trachea tissue engineering are (1) utilization of decellularized matrices using allogenic trachea or other tubular organs (e.g., the human aorta, which has been successfully implanted for replacement of bronchus),89 (2) scaffold systems based on polymers with preseeding of chondrocytes and epithelial cells, (3) implant systems that are designed to induce epithelialization in vivo, (4) hybrid systems that use implants with autologous grafts, and (5) fully developed tracheal replacement matured in vitro with bioreactors. The recent developments in full trachea replacements have been reviewed elsewhere,85 so the discussion here will be restricted to the epithelial layer.

Cultured epithelial cells have been used as the main route for epithelialization. However, this approach associates with several issues such as (1) changes in the phenotype of cells during the culture and subsequent loss of specialized cells in the final structure (e.g., lack of basal, goblet, ciliated or clara cells), (2) loss of the cells after implantation, and (3) insufficient coverage, which leads to infection and subsequently restenosis due to extensive granulation. Normal epithelial layer regeneration occurs by both endogenous (resident stem cells) and exogenous (circulating bone marrow derived) stem cells.90 These events, however, need to be regulated with respect to implantation since this procedure by itself causes an acute immune response that can adversely affect the remodeling.

The quality of the final epithelial layer in the trachea can be judged by the presence of different functional cell types. The different cell types of an artificial epithelium can be distinguished in vitro, by their differential expression of surface markers. For example, in the airway epithelium, this can be achieved by investigating cytokeratin expression levels such as CK5, CK14 (marker of basal cells), and CK18 (marker of ciliated and secretory cells).91 Current in vitro culture methods partially enable the preservation (i.e., prevent dedifferentiation) of the different cell types of the respiratory epithelium,92 however, research is still underway to develop a functional epithelium that is successful in vivo. It has been shown that the number of goblet cells steadily decreases in culture and also the cells are generally found in the process of metaplasia rather than the basal cell phenotype. Thus, it is important to devise ways to maintain phenotypes that ensure steady renewal of epithelial cells together with healthy levels of mucus secretion.91 The best way to obtain nearly fully differentiated epithelium in vitro is by using air–liquid interface culture methods, where the expression profile of the epithelial cells are closer to that of in vivo expression.93 However, recent studies have shown that the use of embryonic stem cells can be used to bypass the air–liquid culture step.94 Nevertheless, this approach requires longer culture periods and does not represent the overall diversity of the cells in the airway epithelium. The cell phenotype can also be affected by changing the substrate to hyaluronan or collagen type IV. Hyaluronan was shown to induce ciliary differentiation of respiratory epithelium together with increased expression of genes related to the secretory cells.95 In addition, the composition of the culture media and the cell culture conditions (e.g., spheroid cultures in suspensions or air–liquid interface culture systems) need to be properly controlled in such settings.96

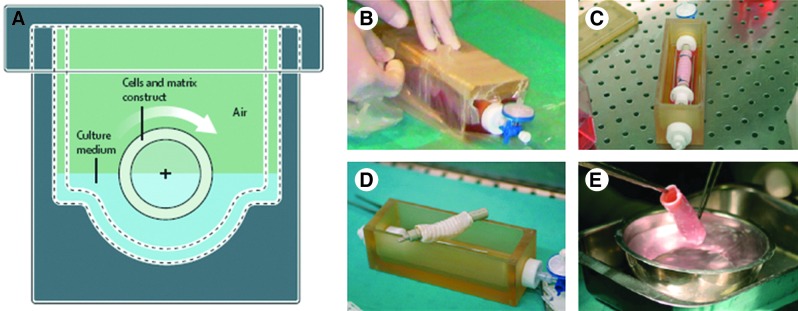

In tracheal tissue engineering efforts,97 significant steps have been taken both through in situ methods and bioreactor systems. Two groups have reported successful human implantation of tissue engineered tracheas in 2008.74,86 To obtain a ciliated epithelium that covers the lumen of the decellularized trachea, a bioreactor system was used in one case. The final prototypes of these tissue engineered trachea were made using a complex double rotating bioreactor system shown in Figure 5. This system can accommodate both stem cells and epithelial cells, to differentiate into chondrocytes and to form the ciliated epithelial layer, respectively.98 After maturation in vitro, the final structure had mechanical properties that were similar to that of the native trachea and a functional epithelial layer. Despite its usefulness, this approach is complex and resource intensive. As such, its transfer to ill-equipped areas can be problematic. The production of epithelium especially for large defects is still a limiting factor in all these efforts. A more generalized approach to solve this problem, which can also be applied to the epithelium, would be an improvement for better clinical outcomes. Rather than attempting to meet generally contradictory needs of several cell types in coculture systems, simultaneous production of different parts followed by a bottom-up construction step before implantation could simplify the production, storage, and implantation conditions.

FIG. 5.

Successful tissue-engineering systems with an epithelial layer. (A–E) Production of an artificial trachea in a double rotating chamber bioreactor with autologous cells and an allogenic decellularized trachea, the final tissue has been implanted in a patient and the patient has regained her health.74 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Modular Epithelial Layers and Their Application in Organ-on-a-Chip Systems

Cell-based therapies and tissue engineering approaches are closely related. One of the distinguishing factors in tissue engineering is that the function-related physical properties are simulated either through using biomimetic scaffolds or by inducing the cells to produce the necessary structures. When such structures are composed of different cell types, the achievement of the complexity with microscale accuracy is rather challenging. The developments in micro- and nanofabrication technologies combined with the advances in modular tissue engineering may address such issues. In the last few years, modular approaches have been developed to circumvent these problems.99 These systems offer greater control over cell–cell interactions100,101 and building of the multicellular complexity by utilization of different building blocks.102 These approaches would be helpful in the prevention of several bulk material-related problems such as nutrition or gas transfer. Formation of different epithelial layer structures by these methodologies is an attractive approach, not only for modeling purposes, but also for some clinical applications. For example, local loss of the epithelium, which is created by certain existing clinical interventions such as prolonged intubation can be quickly solved by these modular approaches. If there is a drainage of stem cell reservoirs for an epithelial tissue (such as corneal epithelium) microtissues can be used in combination with therapeutic cloning to acquire fresh stem cell reservoirs.76 With modular methods, it is possible to understand the differentiation behavior of epithelial cells in smaller areas to determine pathways that expedite the process, whereas getting results with the use of conventional methods generally takes up to 2 weeks.

Microscale modular epithelial constructs can also be put together to obtain epithelial coverage of larger areas by modular tissue engineering approaches. One of the most commonly used materials in modular tissue engineering is hydrogels. Hydrogels are superior structures as scaffolds for organs such as the cornea.103 The stiffness of the gels is an important factor in the cellular response to the gel surface. The effect of stiffness on the epithelial cell attachment and proliferation on thin gels has been shown previously.104 It is, therefore, possible to design hydrogels suitable for epithelial cell differentiation. The presence of a BM-like surface also improves the responsiveness of the epithelial cells to soluble factors. This behavior was observed in the presence of BM in the case of mammary epithelial cells' response to insulin and prolactin.105

Modular engineered epithelia can be used for in-situ epithelialization or transfer of epithelial layers onto the cell functionalized implants and scaffolds. The advantages of such systems include the reduction of production period, likelihood of modifying epithelial cells by genetic engineering, or cell surface modifications by nano- and microparticles. For example, it has been shown that lentivirus transducted epithelial spheroids can be used for re-epithelialization of a denuded rat tracheal BM, which also solves the problem of low efficacy of transduction in vivo due to the mucus barrier. The advantage of spheroid cultures is the long-term preservation of differentiated state compared to 2D culture106 and also the modular nature of the final product (Fig. 6).

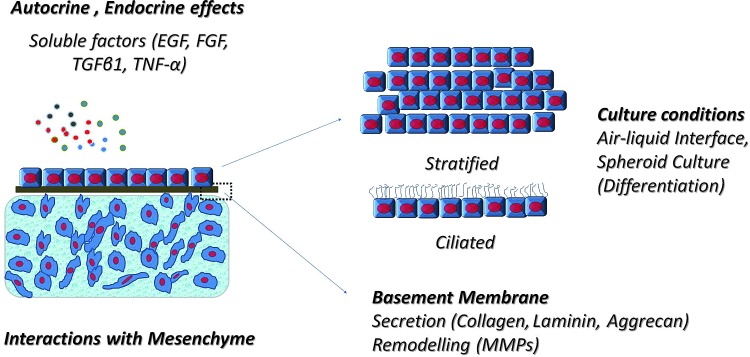

FIG. 6.

Advantages of modular microscale epithelial tissues. The quality of an artificial epithelial layer can be controlled by soluble factors, culture conditions, the presence of mesenchyme and the culture substrate, that is, basement membrane equivalents made of thin biomaterial films. These factors can be adjusted in small volumes, which would render the experiments faster and more reproducible. It will also facilitate production of transferable epithelial patches. EGF, epidermal growth factor; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

When carriers are used, the adhesive properties of the carrier become important to ensure that the epithelial tissue stays in the implantation site.107,108 There is substantial literature for the controlled delivery systems on the adhesion of gels and other structures such as microcapsules in the respiratory and digestive tract and these data can be used for optimizing cell carriers.109 The carriers should either promote epithelial functions by themselves or act as facilitators for promoting the effects of mesenchymal cells on epithelial function.110 A possible method is to use anisotropic adhesive structures that enable instant attachment of the modular epithelial layer onto the tissue or the scaffold. One such method was developed by using modified chondroitin sulfate to act as a bridge between the implant and the tissue.111 The application of epithelial grafts in wet environments necessitates utilization of bioadhesives for improving their retention particularly in the case of vascular implant endothelialization. Aside from conventional adhesives such as fibrin gel, other possibilities are available such as gelatin-based adhesives112 or gecko-inspired hierarchical structures. These approaches can also be used to stick the structures to wet surfaces.113 It is also possible to obtain sticky surfaces by stereolithography, dip transfer, or dry templating methods.114–116

Microscale tissues have been used for developing (1) microepithelial layers in transwell plates and their characterization and (2) microfluidic systems for producing epithelial cell colonies and 3D models of kidney epithelium.117 Another application was the production of functional alveolar–capillary interface for screening purposes.118 Transwell systems can be further modified via micropatterning both sides of the porous membrane to develop coculture of epithelial cells with a wide range of cell types.119 This approach decreases the processing time for developing a polarized epithelium and allows monitoring of several microepithelial tissues under the same experimental conditions.120 This method is a powerful tool for monitoring the effect of physical constraints on the epithelial layer by micropatterned surfaces. For example, the induction of epithelial to mesenchymal differentiation by confining them in micropatterns has been demonstrated.121 Moreover, by monitoring autocrine and endocrine effects in small population of cells, it may be possible to acquire more information about the epithelial cancer cell activity.122 For example, the transepidermal electrical resistance is a well-established measure of integrity of an epithelial layer and this information can be obtained via bioimpedance measurements.123 The development of an epithelial barrier that mimics physiological or pathological conditions is an efficient strategy for assessing the bioavailability of drugs and design of the next generation of pharmaceuticals.

Microscale tissues are a new paradigm for high-resolution monitoring of biological events at the tissue level in a controlled microenvironment. The developments in microscopy techniques, methods for the determination of patient-related differences in epithelial cells, and capacity to migrate to close wounded areas would provide important clinically relevant information for predicting regeneration.124 Biophotonic methods, which are based on either bioluminescence such as luciferase catalyzed reactions or fluorescence within the body are used for noninvasive monitoring of tissue-engineered constructs. These techniques can either be used for the detection of epithelium formation or infection.125 The demand for monitoring tissue repair of easily accessible organs such as the larynx, esophagus, and trachea is anticipated to rapidly escalate the use of such noninvasive imaging tools in the near future. Microscale epithelial tissues can be used in organ-on-a-chip applications, which can be used to study specific interactions between different tissues and generate miniaturized organ models (such as the interface between the respiratory epithelium and vascular endothelium). This kind of complex organ-on-a-chip structures are favorable for determining the patient-specific responses, such as migration of epithelial cells upon injury or their reaction to bioactive molecules, which would be beneficial in personalized medicine applications.126 Organ-on-a-chip systems for the lung and liver have already been developed, which contain multiple cell types.118,127 There are also efforts to incorporate other components of organs, such as microbial flora of intestine in organ-on-a-chip structures.128 By having porous micropillar structures, it is possible to imitate the architecture of gastrointestinal epithelium and thus obtain a reliable microscale model of drug absorption.129 As shown in Figure 7, it is possible to obtain microvilli-mimicking architectures by using stereolithography techniques on membranes produced from SU-8 (an epoxy-based photoresist) on silicon micropillars. By controlling the spacing and the size of the micropillar, it is possible to control the distribution of intestinal epithelial cells. One of the main advantages of such systems is the precise control over the delivery of bioactive agents from both apical and basolateral sides. Epithelial structures are especially important for body-on-a-chip applications as they will be the first contact point between different parts of the whole system and their ability to mimic physiological conditions will determine the fidelity of the metabolic model. The clinical developments and the information obtained from the static models described above can be used to obtain epithelial structures faithful to each organ.

FIG. 7.

Mimicking the microvilli structure for gastrointestinal epithelium models. Porous SU-8 membranes on silicon pillars supported the growth of the gastrointestinal epithelial cells (Caco-2) and the cellular distribution and contact is pillar size and distance dependent (a–d). In this way, a small cross section of gastrointestinal epithelium can be obtained as a model tissue.129 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Conclusions

The presence of a functional epithelium is crucial for the proper function of many organs. Thus, a great deal of tissue engineering research has focused on recreating epithelial tissues in vitro with promising results in the fabrication of organs such as the bladder and trachea. Therefore, it is anticipated that tissue engineering approaches will be successful in near future for regeneration of other tissues. For the case of epithelium, this success relies on better mimicking the BM structure, improving the control over epithelial cell migration on biomaterials, and engineering the interactions of epithelial cells with mesenchymal cells. As the capabilities in the area of regenerative medicine continue to increase, complex microscale models of tissues as platforms for drug discovery and disease modeling will also be developed. Production of such systems as models for the basic research would also benefit regenerative medicine by providing a better understanding of in vitro engineered epithelium and, in turn, can facilitate their clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnology, National Institutes of Health (HL092836, EB02597, AR057837, and HL099073), the National Science Foundation (DMR0847287), BBSRC (grant number BB/H011293/1), and the Office of Naval Research Young Investigator award, Région Alsace and Pôle Matériaux et Nanosciences d'Alsace (PMNA).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Lindsay M. Clinical experience and applications of drug-eluting stents in the noncoronary vasculature, bile duct and esophagus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:447. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W. Ahluwalia I.P. Yelick P.C. Three dimensional dental epithelial-mesenchymal constructs of predetermined size and shape for tooth regeneration. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7995. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ardizzone S. Porro G.B. Biologic therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Drugs. 2005;65:2253. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coraux C. Hajj R. Lesimple P. Puchelle E. Repair and regeneration of the airway epithelium. Med Sci. 2005;21:1063. doi: 10.1051/medsci/200521121063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mangoni M.L. Host-defense peptides: from biology to therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2157. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0709-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Priya S.G. Jungvid H. Kumar A. Skin tissue engineering for tissue repair and regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:105. doi: 10.1089/teb.2007.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu P. Deng Z.H. Han S.F. Liu T. Wen N. Lu W., et al. Tissue-engineered skin containing mesenchymal stem cells improves burn wounds. Artif Organs. 2008;32:925. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oberpenning F. Meng J. Yoo J.J. Atala A. De novo reconstitution of a functional mammalian urinary bladder by tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:149. doi: 10.1038/6146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omori K. Nakamura T. Kanemaru S. Asato R. Yamashita M. Tanaka S., et al. Regenerative medicine of the trachea: the first human case. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:429. doi: 10.1177/000348940511400603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bianco P. Robey P.G. Stem cells in tissue engineering. Nature. 2001;414:118. doi: 10.1038/35102181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coraux C. Nawrocki-Raby B. Hinnrasky J. Kileztky C. Gaillard D. Dani C., et al. Embryonic stem cells generate airway epithelial tissue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:87. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0079RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J. Yamato M. Shimizu T. Sekine H. Ohashi K. Kanzaki M., et al. Reconstruction of functional tissues with cell sheet engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5033. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shier D. Butler J. Lewis R. Hole's Human Anatomy and Physiology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sell S. Barnes C. Smith M. McClure M. Madurantakam P. Grant J., et al. Extracellular matrix regenerated: tissue engineering via electrospun biomimetic nanofibers. Polym Int. 2007;56:1349. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zilberman M. Eberhart R.C. Drug-eluting bioresorbable stents for various applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2006;8:153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.013106.151418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong K.U. Reynolds S.D. Watkins S. Fuchs E. Stripp B.R. In vivo differentiation potential of tracheal basal cells: evidence for multipotent and unipotent subpopulations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L643. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00155.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joo N.S. Wu J.V. Krouse M.E. Saenz Y. Wine J.J. Optical method for quantifying rates of mucus secretion from single submucosal glands. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2001;281:L458. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.2.L458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sancho E. Batlle E. Clevers H. Live and let die in the intestinal epithelium. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:763. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powell D.W. Adegboyega P.A. Di Mari J.F. Mifflin R.C. Epithelial cells and their neighbors, I. role of intestinal myofibroblasts in development, repair, and cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G2. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00075.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proud D. Leigh R. Epithelial cells and airway diseases. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:186. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J. Bian Z. Kuijpers-Jagtman A.M. Von den Hoff J.W. Skin and oral mucosa equivalents: construction and performance. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2010;13:11. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2009.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dongari-Bagtzoglou A. Kashleva H. Development of a highly reproducible three-dimensional organotypic model of the oral mucosa. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2012. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mooney D.J. Vandenburgh H. Cell delivery mechanisms for tissue repair. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:205. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yen C.-M. Chan C.-C. Lin S.-J. High-throughput reconstitution of epithelial-mesenchymal interaction in folliculoid microtissues by biomaterial-facilitated self-assembly of dissociated heterotypic adult cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4341. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Y. Leong M.F. Ong W.F. Chan-Park M.B. Chian K.S. Esophageal epithelium regeneration on fibronectin grafted poly(L-lactide-co-caprolactone) (PLLC) nanofiber scaffold. Biomaterials. 2007;28:861. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao B. Kadomatsu K. Hosaka Y. Construction of synthetic dermis and skin based on a self-assembled peptide hydrogel scaffold. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2385. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vrana N.E. Dupret-Bories A. Bach C. Chaubaroux C. Coraux C. Vautier D., et al. Modification of macroporous titanium tracheal implants with biodegradable structures: Tracking in vivo integration for determination of optimal in situ epithelialization conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:2134. doi: 10.1002/bit.24456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neal R.A. McClugage S.G. Link M.C. Sefcik L.S. Ogle R.C. Botchwey E.A. Laminin nanofiber meshes that mimic morphological properties and bioactivity of basement membranes. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009;15:11. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2007.0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayakawa T. Yoshinari M. Nitta K. Inoue K. Collagen nanofiber on titanium or partially stabilized zirconia by electrospray deposition. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2010;19:5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hajicharalambous C.S. Lichter J. Hix W.T. Swierczewska M. Rubner M.F. Rajagopalan P. Nano- and sub-micron porous polyelectrolyte multilayer assemblies: biomimetic surfaces for human corneal epithelial cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4029. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai R.J. Li L.M. Chen J.K. Reconstruction of damaged corneas by transplantation of autologous limbal epithelial cells. New Engl J Med. 2000;343:86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007133430202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kundu A.K. Gelman J. Tyson D.R. Composite thin film and electrospun biomaterials for urologic tissue reconstruction. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:207. doi: 10.1002/bit.22912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noh H.K. Lee S.W. Kim J.M. Oh J.E. Kim K.H. Chung C.P., et al. Electrospinning of chitin nanofibers: Degradation behavior and cellular response to normal human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3934. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vrana N.E. Dupret A. Coraux C. Vautier D. Debry C. Lavalle P. Hybrid titanium/biodegradable polymer implants with an hierarchical pore structure as a means to control selective cell movement. Plos One. 2011;6:e20480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risbud M. Endres M. Ringe J. Bhonde R. Sittinger M. Biocompatible hydrogel supports the growth of respiratory epithelial cells: possibilities in tracheal tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;56:120. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200107)56:1<120::aid-jbm1076>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinikoglu B. Carlos Rodriguez-Cabello J. Damour O. Hasirci V. The influence of elastin-like recombinant polymer on the self-renewing potential of a 3D tissue equivalent derived from human lamina propria fibroblasts and oral epithelial cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5756. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolli C.G. Nakayama H. Yamaguchi K. Spatz J.P. Kemkemer R. Nakanishi J. Switchable adhesive substrates: revealing geometry dependence in collective cell behavior. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2409. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagpal R. Patel A. Gibson M.C. Epithelial topology. Bioessays. 2008;30:260. doi: 10.1002/bies.20722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chistiakov D.A. Endogenous and exogenous stem cells: a role in lung repair and use in airway tissue engineering and transplantation. J Biomed Sci. 2010;17:92. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-17-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agle K.A. Vongsa R.A. Dwinell M.B. Chemokine stimulation promotes enterocyte migration through laminin-specific integrins. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G968. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00208.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koshikawa N. Giannelli G. Cirulli V. Miyazaki K. Quaranta V. Role of cell surface Metalloprotease Mt1-Mmp in epithelial cell migration over Laminin-5. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:615. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shastri V.P. In vivo engineering of tissues: biological considerations, challenges, strategies, and future directions. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3246. doi: 10.1002/adma.200900608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mori H. Gjorevski N. Inman J.L. Bissell M.J. Nelson C.M. Self-organization of engineered epithelial tubules by differential cellular motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901269106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diehl K.A. Foley J.D. Nealey P.F. Murphy C.J. Nanoscale topography modulates corneal epithelial cell migration. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2005;75A:603. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fong E. Tzlil S. Tirrell D.A. Boundary crossing in epithelial wound healing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008291107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atala A. Engineering organs. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2009;20:575. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cartwright L. Farhat W.A. Sherman C. Chen J. Babyn P. Yeger H., et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to quantify VEGF-enhanced tissue-engineered bladder graft neovascularization: pilot study. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2006;77A:390. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkpatrick C.J. Fuchs S. Hermanns M.I. Peters K. Unger R.E. Cell culture models of higher complexity in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5193. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zorlutuna P. Jeong J.H. Kong H. Bashir R. Stereolithography-based hydrogel microenvironments to examine cellular interactions. Adv Funct Mater. 2011;21:3642. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hofmann A. Ritz U. Verrier S. Eglin D. Alini M. Fuchs S., et al. The effect of human osteoblasts on proliferation and neo-vessel formation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells in a long-term 3D co-culture on polyurethane scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4217. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirkpatrick C.J. Fuchs S. Unger R.E. Co-culture systems for vascularization - Learning from nature. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:291. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zani B.G. Kojima K. Vacanti C.A. Edelman E.R. Tissue-engineered endothelial and epithelial implants differentially and synergistically regulate airway repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802463105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Honda M.J. Tsuchiya S. Sumita Y. Sagara H. Ueda M. The sequential seeding of epithelial and mesenchymal cells for tissue-engineered tooth regeneration. Biomaterials. 2007;28:680. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Honda M.J. Shinohara Y. Hata K.I. Ueda M. Subcultured odontogenic epithelial cells in combination with dental mesenchymal cells produce enamel-dentin-like complex structures. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:833. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahjour S.B. Ghaffarpasand F. Wang H.J. Hair follicle regeneration in skin grafts: current concepts and future perspectives. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2012;18:15. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pageau S.C. Sazonova O.V. Wong J.Y. Soto A.M. Sonnenschein C. The effect of stromal components on the modulation of the phenotype of human bronchial epithelial cells in 3D culture. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7169. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gray F.L. Turner C.G. Ahmed A. Calvert C.E. Zurakowski D. Fauza D.O. Prenatal tracheal reconstruction with a hybrid amniotic mesenchymal stem cells–engineered construct derived from decellularized airway. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green N. Huang Q. Khan L. Battaglia G. Corfe B. MacNeil S., et al. The development and characterization of an organotypic tissue-engineered human esophageal mucosal model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1053. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu J. Mao J.J. Chen L. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions as a working concept for oral mucosa regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2011;17:25. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2010.0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vrana N.E. Builles N. Justin V. Bednarz J. Pellegrini G. Ferrari B., et al. Development of a reconstructed cornea from collagen-chondroitin sulfate foams and human cell cultures. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5325. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rainer C. Wechselberger G. Bauer T. Neumeister M.W. Lille S. Mowlavi A., et al. Transplantation of tracheal epithelial cells onto a prefabricated capsule pouch with fibrin glue as a delivery vehicle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:1187. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.113936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Y.W. Liu W.H. Hayward S.W. Cunha G.R. Baskin L.S. Plasticity of the urothelial phenotype: Effects of gastro-intestinal mesenchyme/stroma and implications for urinary tract reconstruction. Differentiation. 2000;66:126. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2000.660207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koo J.P. Kim C.-H. Lee J.-G. Kim K.-S. Yoon J.-H. Airway reconstruction with carrier-free cell sheets composed of autologous nasal squamous epithelium. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1750. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3180f62b78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tan Q. Steiner R. Yang L. Welti M. Neuenschwander P. Hillinger S., et al. Accelerated angiogenesis by continuous medium flow with vascular endothelial growth factor inside tissue-engineered trachea. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:806. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kanzaki M. Yamato M. Hatakeyama H. Kohno C. Yang J. Umemoto T., et al. Tissue engineered epithelial cell sheets for the creation of a bioartificial trachea. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1275. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishida K. Yamato M. Hayashida Y. Watanabe K. Yamamoto K. Adachi E., et al. Corneal reconstruction with tissue-engineered cell sheets composed of autologous oral mucosal epithelium. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bader A. Macchiarini P. Moving towards in situ tracheal regeneration: the bionic tissue engineered transplantation approach. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kunisaki S.M. Freedman D.A. Fauza D.O. Fetal tracheal reconstruction with cartilaginous grafts engineered from mesenchymal amniocytes. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:675. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Donnenberg V.S. Zimmerlin L. Rubin J.P. Donnenberg A.D. Regenerative therapy after cancer: what are the risks? Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:567. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2010.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park K.S. Wells J.M. Zorn A.M. Wert S.E. Laubach V.E. Fernandez L.G., et al. Transdifferentiation of ciliated cells during repair of the respiratory epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:151. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0332OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wendt M. Tian M. Schiemann W. Deconstructing the mechanisms and consequences of TGF-β-induced EMT during cancer progression. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:85. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mani S.A. Guo W. Liao M.-J. Eaton E.N. Ayyanan A. Zhou A.Y., et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lutolf M.P. Hubbell J.A. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:47. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Macchiarini P. Jungebluth P. Go T. Asnaghi M.A. Rees L.E. Cogan T.A., et al. Clinical transplantation of a tissue-engineered airway. Lancet. 2008;372:2023. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61598-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dupuit F. Gaillard D. Hinnrasky J. Mongodin E. De Bentzmann S. Copreni E., et al. Differentiated and functional human airway epithelium regeneration in tracheal xenografts. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:L165. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.1.L165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shieh S.J. Vacanti J.P. State-of-the-art tissue engineering: From tissue engineering to organ building. Surgery. 2005;137:1. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee K.H. Tissue-engineered human living skin substitutes: development and clinical application. Yonsei Med J. 2000;41:774. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2000.41.6.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guerra L. Dellambra E. Panacchia L. Paionni E. Tissue engineering for damaged surface and lining epithelia: stem cells, current clinical applications, and available engineered tissues. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2009;15:91. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Badylak S.F. Weiss D.J. Caplan A. Macchiarini P. Engineered whole organs and complex tissues. Lancet. 379:943. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bhargava S. Patterson J.M. Inman R.D. MacNeil S. Chapple C.R. Tissue-engineered buccal mucosa urethroplasty - Clinical outcomes. Eur Urol. 2008;53:1263. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Atala A. Bauer S.B. Soker S. Yoo J.J. Retik A.B. Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet. 2006;367:1241. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lauer G. Schimming R. Tissue-engineered mucosa graft for reconstruction of the intraoral lining after freeing of the tongue: a clinical and immunohistologic study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59:169. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang S.H. Nagrath D. Liver tissue engineering. In: Burdick J.A., editor; Mauck R.L., editor. Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications: A Review of the Past and Future Trends. NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 389–419. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lange P. Fishman J.M. Elliott M.J. De Coppi P. Birchall M.A. What can regenerative medicine offer for infants with laryngotracheal agenesis? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:544. doi: 10.1177/0194599811419083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ott L.M. Weatherly R.A. Detamore M.S. Overview of tracheal tissue engineering: clinical need drives the laboratory approach. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:2091. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Omori K. Tada Y. Suzuki T. Nomoto Y. Matsuzuka T. Kobayashi K., et al. Clinical application of in situ tissue engineering using a scaffolding technique for reconstruction of the larynx and trachea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117:673. doi: 10.1177/000348940811700908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Go T. Jungebluth P. Baiguero S. Asnaghi A. Martorell J. Ostertag H., et al. Both epithelial cells and mesenchymal stem cell-derived chondrocytes contribute to the survival of tissue-engineered airway transplants in pigs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:437. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schultz P. Vautier D. Richert L. Jessel N. Haikel Y. Schaaf P., et al. Polyelectrolyte multilayers functionalized by a synthetic analogue of an anti-inflammatory peptide, alpha-MSH, for coating a tracheal prosthesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2621. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martinod E. Radu D.M. Chouahnia K. Seguin A. Fialaire-Legendre A. Brillet P.-Y., et al. Human transplantation of a biologic airway substitute in conservative lung cancer surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:837. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Roomans G.M. Tissue engineering and the use of stem/progenitor cells for airway epithelium repair. Eur Cell Mater. 2010;19:284. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v019a27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Endres M. Leinhase I. Kaps C. Wentges M. Unger M. Olze H., et al. Changes in the gene expression pattern of cytokeratins in human respiratory epithelial cells during culture. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:390. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Widdicombe J.H. Sachs L.A. Morrow J.L. Finkbeiner W.E. Expansion of cultures of human tracheal epithelium with maintenance of differentiated structure and function. Biotechniques. 2005;39:249. doi: 10.2144/05392RR02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pezzulo A.A. Starner T.D. Scheetz T.E. Traver G.L. Tilley A.E. Harvey B.-G., et al. The air-liquid interface and use of primary cell cultures are important to recapitulate the transcriptional profile of in vivo airway epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L25. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00256.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang Y. Wong L.B. Mao H. Induction of ciliated cells from avian embryonic stem cells using three-dimensional matrix. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:929. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang T.W. Chan Y.H. Cheng P.W. Young Y.H. Lou P.J. Young T.H. Increased mucociliary differentiation of human respiratory epithelial cells on hyaluronan-derivative membranes. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:1191. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bukowy Z. Zietkiewicz E. Witt M. In vitro culturing of ciliary respiratory cells-a model for studies of genetic diseases. J Appl Genet. 2011;52:39. doi: 10.1007/s13353-010-0005-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Grillo H.C. Tracheal replacement: a critical review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1995. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Asnaghi M.A. Jungebluth P. Raimondi M.T. Dickinson S.C. Rees L.E. Go T., et al. A double-chamber rotating bioreactor for the development of tissue-engineered hollow organs: from concept to clinical trial. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5260. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gauvin R. Khademhosseini A. Microscale technologies and modular approaches for tissue engineering: moving toward the fabrication of complex functional structures. Acs Nano. 2011;5:4258. doi: 10.1021/nn201826d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fernandez J.G. Khademhosseini A. Micro-masonry: construction of 3D structures by microscale self-assembly. Adv Mater. 2010;22:2538. doi: 10.1002/adma.200903893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yanagawa F. Kaji H. Jang Y.H. Bae H. Du Y.A. Fukuda J., et al. Directed assembly of cell-laden microgels for building porous three-dimensional tissue constructs. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2011;97A:93. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.33034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Swiston A.J. Gilbert J.B. Irvine D.J. Cohen R.E. Rubner M.F. Freely suspended cellular “Backpacks” lead to cell aggregate self-assembly. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1826. doi: 10.1021/bm100305h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Duan X. Sheardown H. Dendrimer crosslinked collagen as a corneal tissue engineering scaffold: Mechanical properties and corneal epithelial cell interactions. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4608. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kocgozlu L. Lavalle P. Koenig G. Senger B. Haikel Y. Schaaf P., et al. Selective and uncoupled role of substrate elasticity in the regulation of replication and transcription in epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:29. doi: 10.1242/jcs.053520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rosso F. Giordano A. Barbarisi M. Barbarisi A. From cell-ECM interactions to tissue engineering. J Cell Physiol. 2004;199:174. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Castillon N. Avril-Delplanque A. Coraux C. Delenda C. Peault B. Danos O., et al. Regeneration of a well-differentiated human airway surface epithelium by spheroid and lentivirus vector-transduced airway cells. J Gene Med. 2004;6:846. doi: 10.1002/jgm.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Higa K. Shimmura S. Kato N. Kawakita T. Miyashita H. Itabashi Y., et al. Proliferation and differentiation of transplantable rabbit epithelial sheets engineered with or without an amniotic membrane carrier. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:597. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lai J.-Y. Lu P.-L. Chen K.-H. Tabata Y. Hsiue G.-H. Effect of charge and molecular weight on the functionality of gelatin carriers for corneal endothelial cell therapy. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1836. doi: 10.1021/bm0601575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Peppas N.A. Sahlin J.J. Hydrogels as mucoadhesive and bioadhesive materials: a review. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1553. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)00307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yang T.-L. Chitin-based materials in tissue engineering: applications in soft tissue and epithelial organ. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:1936. doi: 10.3390/ijms12031936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang D.-A. Varghese S. Sharma B. Strehin I. Fermanian S. Gorham J., et al. Multifunctional chondroitin sulphate for cartilage tissue-biomaterial integration. Nat Mater. 2007;6:385. doi: 10.1038/nmat1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]