Pancreatic cancer (PaC) is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States. It has a dismal 5 year survival rate of <5%, which is the result of a combination of factors including our inability to screen for sporadic PaC, frequent presentation with advanced malignancy at the time of clinical presentation, and lack of effective treatment options. Efforts to improve these poor clinical outcomes require additional understanding of PaC risk factors, and mechanisms of carcinogenesis and tumor migration. One interesting clinical observation in PaC is its frequent association with diabetes mellitus (DM), which may be an important clue needed to make progress.

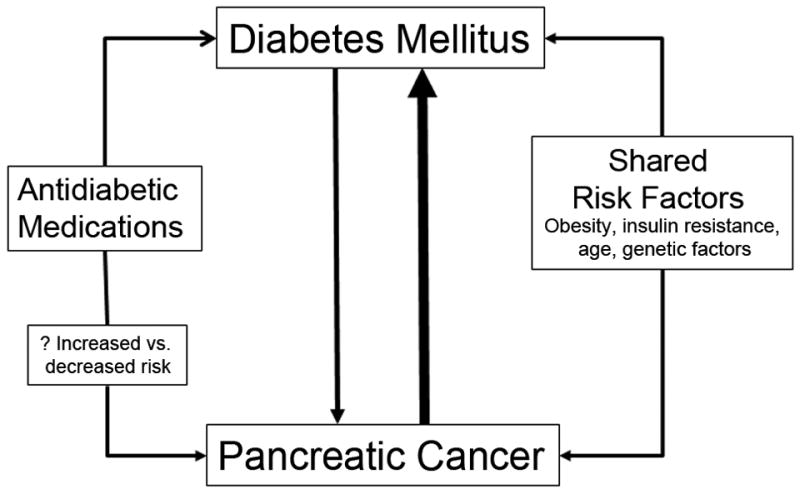

The interaction between DM and PaC as regards its etiology and risk factors is complex (Figure). Here we will focus on the bidirectional association which suggests that while DM is a risk factor for the development of PaC, the cancer also causes DM as a paraneoplastic syndrome.

Figure.

The bidirectional association between pancreatic cancer and diabetes mellitus is complex.

In their systematic review, Raghavan and colleagues provide an extensive description of clinical data examining the association between DM and PaC including the risk for developing PaC, postoperative complications, and postoperative survival1. Their review consolidates studies published from a variety of vantage points including epidemiology, gastroenterology, oncology, and surgery. To accurately interpret these studies it is important to recognize the significant heterogeneity in regards to study design, including definitions of DM, duration of DM, and post-operative complications. There is also wide variability in confounding variables considered in statistical analyses (e.g., operative tumor and medication data), so the use of pooled estimates and collective frequencies are not necessarily reliable. Nevertheless, the reader is easily able to appreciate the range and consistent effect of DM in the individual studies. We have selected six key conclusions, and highlight their implications for clinical practice and future investigations.

1. Long-standing diabetes mellitus is a modest risk factor for pancreatic cancer

A large number of epidemiologic studies, both case-control and cohort, have studied the association between DM and PaC. Meta-analyses of these studies have consistently demonstrated an approximately 2-fold increased risk of PaC in those with DM compared to those without DM, and the association appears even stronger in cohort studies than case-control studies2-4. The association is somewhat weaker when only DM >5 years in duration is considered2, 3. This association remains after adjusting for shared risk factors for DM, including obesity and age4.

2. New-onset diabetes mellitus is a harbinger of pancreatic cancer

The prevalence of DM in PaC varies depending on the method of ascertainment of DM, with higher rates in studies screening for DM compared to those using chart review or self-reported DM5-7. When evaluated by glucose tolerance testing or fasting glucose measurements, hyperglycemia occurs in up to 80% of PaC patients at the time of diagnosis, while almost 45-65% of PaC patients have DM6, 7. Even though DM is observed in a variety of common cancers, the prevalence was not higher in these cancers compared to non-cancer controls with the exception of PaC, suggesting a unique interaction between PaC and DM8.

Conversely, the risk for PaC is increasingly higher in those with DM of new-onset (i.e., DM onset occurring within 36 months of cancer diagnosis)9. In up to three-fourths of PaC patients with DM, the DM is of recent onset7. In one population-based study patients with new-onset DM were 8 times more likely to develop PaC than those without DM10. In this study approximately 1/125 patients with new-onset DM developed PaC within 36 months of meeting criteria for DM10. These data suggest that subjects with new-onset DM are a high risk group for developing PaC and may be a potential target to screen for sporadic PaC11. While prevalent DM is common, truly new-onset (incident) DM over age 50 years is much less common. However, identification of incident DM and additional filters to further enrich this population are needed to make screening for PaC to be feasible11.

3. New-onset diabetes mellitus frequently resolves following pancreatic cancer resection

Pancreatic resection in diabetic subjects would be expected to worsen DM as it is associated with loss of a third or more of pancreatic parenchyma. On the other hand, there is, on average, an 8% loss of body weight following pancreaticoduodenectomy, which should improve glucose tolerance12. While PaC patients with long-standing DM have persistent DM following pancreatic resection, patients with PaC and new-onset DM often experience resolution of diabetes in the postoperative setting, which is associated with a resolution of the pre-operative insulin resistance7, 13, 14

4. New-onset DM in pancreatic cancer is a paraneoplastic phenomenon caused by tumor secreted products

The very high prevalence of new-onset DM that resolves with cancer resection suggests that DM is caused by the cancer. This is not merely the consequence of structural mass effect with loss of beta-cell mass or ductal obstruction as the DM onset precedes visible appearance of a mass15. Also, insulin levels are high in PaC rather than low as would be expected if the DM was due to loss of beta cell mass. Therefore, a humorally-mediated phenomenon is favored whereby PaC induces DM in this subset of patients9. A recent study identified adrenomedullin as a potential diabetogenic factor16. It is overexpressed in human PaC, and overexpression in mice with PaC induces glucose intolerance16. An explanation for the lack of glycemic improvement in those with long-standing DM is unclear, but may be a consequence of permanent loss of beta-cell mass. In summary, the frequent resolution of new-onset DM following cancer surgery suggests that PaC causes DM in an important group of patients. Again, this has potential clinical implications for screening purposes, but also mechanistically may help identify signals involved with cancer growth and survival.

5. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased rates of surgical complications following pancreatic cancer resection

Despite major advances in surgical techniques and postoperative care, complication rates associated with pancreatic surgery continue to remain high (40-50%). Fortunately many complications can be managed non-operatively using either interventional endoscopy and/or radiology. Raghavan et al. systematically show a variety of studies reporting increased rates of surgical complications including pancreatic fistulae, surgical site infection, intraabdominal abscess, and delayed gastric emptying in subjects with preoperative DM1. The association between DM and postoperative complications is not isolated to pancreatic surgery, and has been described in a variety of other surgical areas including cardiothoracic and orthopedic surgery17, 18.

Although the association between DM and surgical complications following cancer resection does not appear to provide any unique insights, it remains clinically relevant. With current emphasis on quality-based care it is increasingly important to address any potentially avoidable morbidity. Since most patients are diabetic preoperatively, or will develop hyperglycemia with either surgical stress or following pancreatic resection, it is important to understand the influence of DM on postoperative complications. Although systematic studies are lagging, it will be important to investigate whether or not perioperative morbidity can be decreased with careful management of pre- and perioperative DM.

6. Survival following pancreatic cancer resection may be worse in those with DM prior to surgery

Data regarding postoperative survival suggest that preoperative DM status may portend a worse prognosis compared to those without DM19-21. Interestingly, the effect appears to be greater in those with new-onset DM compared to long-standing DM20. Although several studies investigated this question, there are a large number of confounding factors that require adjustment prior to pooling results. Despite the lack of this summary statistic, one can appreciate that although some studies show postoperative survival is poorer in those with preoperative DM, others failed to demonstrate an association22, 23. Even if DM status influences postoperative survival, this effect is likely obscured by poor survival attributed to the cancer itself. Ideally, the influence of pre- and perioperative glucose control on survival should be investigated in a prospective manner to carefully collect the needed data. These results would be meaningful to support additional investigations exploring therapeutic targets related to the DM-PaC pathway.

In summary, the present review illuminates the robust literature demonstrating an association between DM and PaC. These data and additional investigations into this association have the potential to improve patient outcomes. Even without complete mechanistic understanding of the DM-PaC interaction, clinical observations suggest the potential of using new-onset DM to screen for sporadic PaC. Future studies are needed to fully realize other clinical applications such as improving perioperative morbidity and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Dr. Chari was supported by the Mayo Clinic Pancreas Cancer SPORE (P50 CA 102701).

Abbreviations

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- PaC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/disclosures: No conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Raghavan SR, Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. The Impact of Perioperative Blood Glucose Levels on Pancreatic Cancer Prognosis and Surgical Outcomes: An Evidence Base Review. Pancreas. 2013 doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182a6db8e. In press with this manuscript. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everhart J, Wright D. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;273:1605–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de Gonzalez A, et al. Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:2076–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben Q, Xu M, Ning X, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of pancreatic cancer: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1928–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noy A, Bilezikian JP. Clinical review 63: Diabetes and pancreatic cancer: clues to the early diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:1223–31. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.5.7962312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Permert J, Ihse I, Jorfeldt L, et al. Pancreatic cancer is associated with impaired glucose metabolism. Eur J Surg. 1993;159:101–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pannala R, Leirness JB, Bamlet WR, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of pancreatic cancer-associated diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:981–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal G, Kamada P, Chari ST. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus in pancreatic cancer compared to common cancers. Pancreas. 2013;42:198–201. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182592c96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sah RP, Nagpal SJ, Mukhopadhyay D, et al. New insights into pancreatic cancer-induced paraneoplastic diabetes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:423–33. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chari ST, Leibson CL, Rabe KG, et al. Probability of pancreatic cancer following diabetes: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:504–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pannala R, Basu A, Petersen GM, et al. New-onset diabetes: a potential clue to the early diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:88–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70337-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seiler CA, Wagner M, Bachmann T, et al. Randomized clinical trial of pylorus-preserving duodenopancreatectomy versus classical Whipple resection-long term results. Br J Surg. 2005;92:547–56. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Permert J, Ihse I, Jorfeldt L, et al. Improved glucose metabolism after subtotal pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. The Br J Surg. 1993;80:1047–50. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogar P, Pasquali C, Basso D, et al. Diabetes mellitus in pancreatic cancer follow-up. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:2827–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelaez-Luna M, Takahashi N, Fletcher JG, et al. Resectability of presymptomatic pancreatic cancer and its relationship to onset of diabetes: a retrospective review of CT scans and fasting glucose values prior to diagnosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2157–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal G, Ramachandran V, Javeed N, et al. Adrenomedullin is Upregulated in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer and Causes Insulin Resistance in beta Cells and Mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1510–1517.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latham R, Lancaster AD, Covington JF, et al. The association of diabetes and glucose control with surgical-site infections among cardiothoracic surgery patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:607–12. doi: 10.1086/501830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han HS, Kang SB. Relations between Long-term Glycemic Control and Postoperative Wound and Infectious Complications after Total Knee Arthroplasty in Type 2 Diabetics. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5:118–23. doi: 10.4055/cios.2013.5.2.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Piccoli A, et al. Survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 1996;83:625–31. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chu CK, Mazo AE, Goodman M, et al. Preoperative diabetes mellitus and long-term survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:502–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0789-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartwig W, Hackert T, Hinz U, et al. Pancreatic cancer surgery in the new millennium: better prediction of outcome. Ann Surg. 2011;254:311–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821fd334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganti AK, Potti A, Koch M, et al. Predictive value of clinical features at initial presentation in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a series of 308 cases. Medical Oncology. 2002;19:233–7. doi: 10.1385/MO:19:4:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dandona M, Linehan D, Hawkins W, et al. Influence of obesity and other risk factors on survival outcomes in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2011;40:931–7. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318215a9b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]