Abstract

The synthesis of a ruthenium complex that catalyzes Z-selective (up to 98% Z) asymmetric ring opening/cross metathesis with high enantioselectivity (up to 95% ee) is reported. Synthesis of the catalyst features the resolution of a chelating NHC alkylidene complex by ligand substitution with a chiral carboxylate.

Olefin metathesis is a powerful carbon-carbon bond forming reaction that is widely used in organic synthesis,1 polymer chemistry,2 materials science,3 and biochemistry.4 Asymmetric olefin metathesis methodologies have proven useful for the synthesis of enantiopure natural products and other biologically-relevant molecules.5 Consequently, the development of chiral catalysts for methods such as asymmetric ring opening/cross metathesis (AROCM) is a field of ongoing interest.6

The earliest catalysts contained molybdenum, and while capable of generating AROCM products in high ee (80 – 99%), suffered from limited substrate scope and functional group compatibility.7 Ruthenium-based catalysts have been developed wherein the chirality is built into the N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand.8 Most of these molybdenum and ruthenium catalysts are capable of performing AROCM with high levels of E-selectivity (up to >98% E).9

Recently, Z-selective AROCM of oxabicycles has been achieved with molybdenum catalysts.10 While Z-selective AROCM has been accomplished with ruthenium catalysts, thus far it has been limited to reactions involving heteroatom-substituted α-olefin cross partners.11 Recent advances have produced ruthenium catalysts with chelating NHC ligands possessing exquisite Z-selectivity in cross metathesis.12 We anticipated that enantiopure versions of the newly developed catalysts would exhibit high Z-selectivity and enantioselectivity in AROCM due to the rigidity imparted by the Ru–C chelate. Herein we report a new homochiral stereogenic-at-ruthenium complex that exhibits high enantioselectivity in the AROCM of norbornene derivatives.

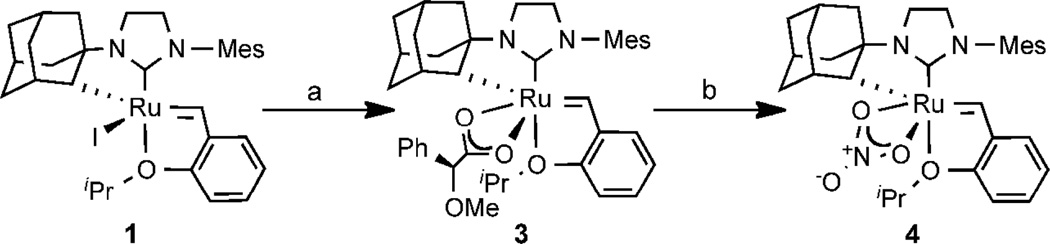

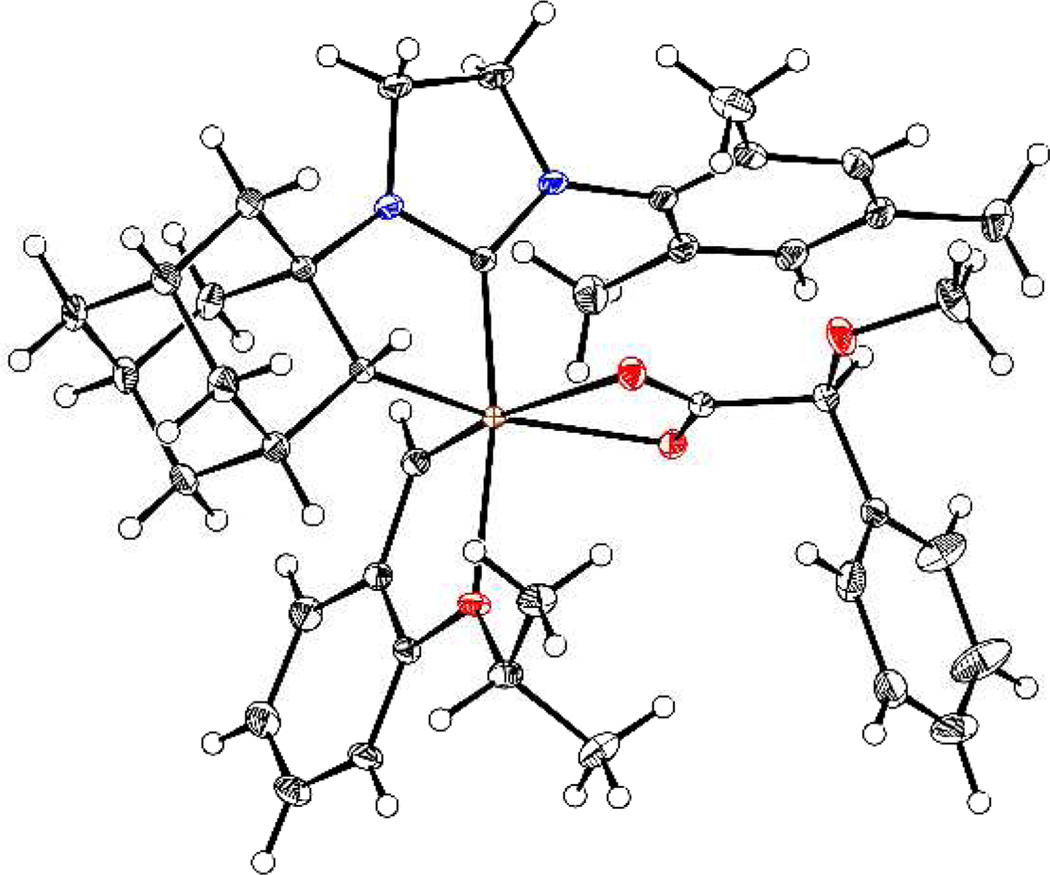

Enantioenriched 4 was synthesized by resolution as shown in Scheme 1. Treatment of racemic iodide 112c with silver carboxylate 2 cleanly formed a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers in 97% yield. Chromatographic separation of the mixture afforded a 45% yield (90% of theoretical maximum) of 3 (>95:5 dr). The absolute stereochemistry of complex 3 was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Figure 1). Sequential treatment of carboxylate 3 with para-toluenesulfonic acid and sodium nitrate produced the enantioenriched nitrate complex 4 in 43% yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Homochiral Complex 4a

a (a) 1. (S)–AgO2CCH(Ph)(OMe) (2, 2 equiv), THF, 23 °C, 1.5 h, 97%; 2. chromatographic separation, 45%; (b) 1. pTsOH•H2O, THF, 5 min; 2. NaNO3, THF/MeOH, 15 min, 43%.

Figure 1.

ORTEP drawing of 3

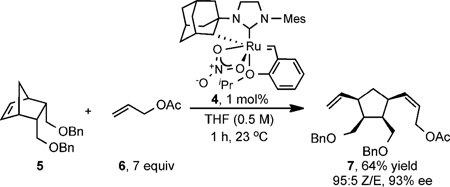

While complex 3 exhibited low enantioselectivity in AROCM, 1 mol% of complex 4 catalyzed the reaction of norbornene 5 with an excess of allyl acetate (6) to produce a 64% yield of diene (1S,2R,3S,4R)-7 with 95% Z-selectivity and 93% ee (eq 1).13 The highly selective reaction produces four contiguous stereocenters on a tetra-substituted cyclopentane ring.

Optimization of the process revealed that 7 equiv. of α-olefin, 1 mol% catalyst loading at 23 °C and 0.5 M concentration in THF afforded the highest yield and selectivity. Ethereal solvents were optimal, with catalyst solubility improved in THF over diethyl ether.

|

(1) |

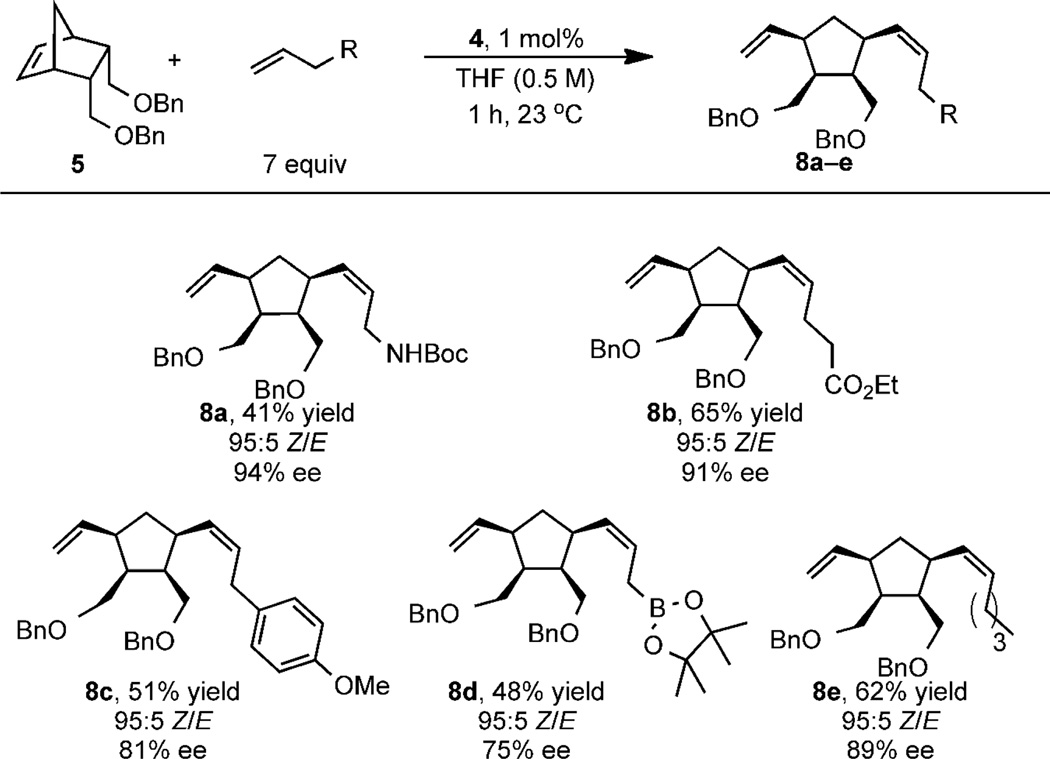

In order to demonstrate the scope of Z-selective catalyst 4, a variety of α-olefins bearing diverse functionality were employed in order to determine their effect on the efficiency and enantioselectivity of the reaction. As illustrated in Table 1, replacing allyl acetate with N-Boc-allylamine provided aminecontaining product 8a in equally high enantioselectivity (94% ee). Utilizing an olefin bearing a remote ester did not impact the Z-selectivity and afforded 8b in 91% ee.

Table 1.

AROCM with Different α-Olefin Partnersa

|

Yields correspond to isolated product; Z/E ratios determined by 500 MHz1H NMR of the crude reaction mixture; ee of pure products measured with chiral SFC

Bulkier allylic substituents such as para-methoxy phenyl and pinacol boronic ester gave products 8c and 8d with moderate enantioselectivity (81% and 75% ee, respectively). A simple α-olefin such as 1-hexene also gave good yield, Z-selectivity, and enantioselectivity (8e, 89% ee), demonstrating that allylic functionality is not required to confer a selective reaction. The examples in Table 1 suggest that catalyst 4 is capable of producing a range of AROCM products.14

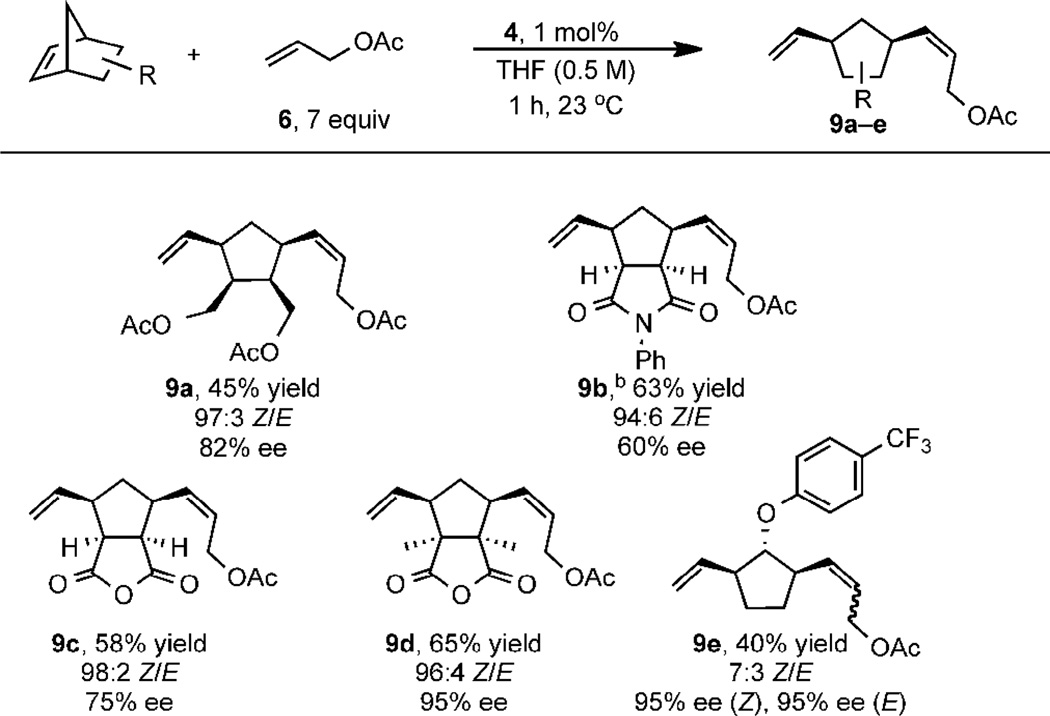

The norbornene component was then altered to understand its impact on Z–selectivity and enantioselectivity. As a basis for comparison, the substrates were treated with 7 equivalents of allyl acetate under the optimized catalytic conditions. Norbornenes bearing coordinating functionality such as acetate (to form 9a) and N-phenyl succinimide (to form 9b) resulted in reduced yield and slower reaction, respectively. The dimethyl substituted anhydride afforded a 65% yield of 9d, which contains two vicinal all-carbon quaternary stereocenters, demonstrating the power of AROCM to afford otherwise synthetically challenging products in high ee (95%). Aryl ether 9e was produced in 95% ee, although interestingly as a 7:3 Z/E mixture. The results in Table 2 support the observation that substrates bearing 2,3-endo substitution react with high Z-selectivity; substrates lacking this substitution pattern show reduced diastereoselectivity.

Table 2.

Influence of Strained Olefin Reactanta

|

Yields correspond to isolated product; Z/E ratios determined by GC; ee of pure products measured with chiral SFC

Conducted at 3 mol% catalyst loading for 5 h.

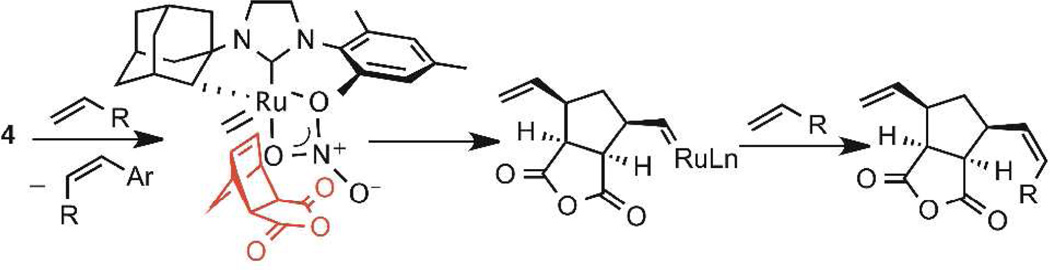

The fact that Z-9e and E-9e are formed in identical enantioenrichment has important mechanistic implications and offers indirect evidence of the active catalytic species. The result suggests that the enantiodetermining step most likely precedes the olefin geometry-determining step.15 This conclusion requires the initial enantiodetermining ring-opening event to occur with a ruthenium methylidene (Scheme 2). Subsequent cross metathesis of the ring-opened product bearing a ruthenium alkylidene with an equivalent of α-olefin would then produce the observed product.

Scheme 2.

Proposed Model of Enantioselectivity

On the basis of this indirect mechanistic evidence and the absolute configuration of the isolated product, we propose that the methylidene shown in Scheme 2 initially reacts with the norbornene component in an enantioselective ring-opening event. It is hypothesized that the enantioselectivity is governed by approach of the methylidene to the less-hindered exo face while the mesityl “cap” forces the bulk of the norbornene component to orient away from the NHC ligand.16 The proposed methylidene is most likely produced by initial cross metathesis of 4 with a molecule of α-olefin, resulting in epimerization at the ruthenium center. Studies are currently underway to better understand the mechanism and origin of enantioselectivity in the AROCM catalyzed by complex 4.

In summary, we have developed an enantioenriched ruthenium metathesis catalyst capable of highly Z-selective and enantioselective ROCM. An NHC ligand that chelates through a Ru–C bond is key to the design of the catalyst, which features a stereogenic Ru atom. The reaction is amenable to modification of both the α-olefin and norbornene component, which significantly broadens the scope of this methodology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was financially supported by the NIH (5R01GM031332-27 to R.H.G.). Thanks to Mr. L. M. Henling for X-ray crystallography. The Bruker KAPPA APEXII X-ray diffractometer was purchased via an NSF CRIF:MU award to the California Institute of Technology (CHE-0639094). Materia, Inc. is thanked for its donation of metathesis catalysts. Drs. Daryl Allen of Materia, Inc. and Scott Virgil of the Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis are thanked for helpful advice.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and spectral data for products; crystallographic information files. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Cossy J, Arseniyadis S, Meyer C. Metathesis in Natural Product Synthesis: Strategies Substrates and Catalysts. 1st ed. Germany: Wiley-VCH Weinheim; 2010. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4490–4527. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Mutlu H, de Espinosa LM, Meier MAR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1404–1445. doi: 10.1039/b924852h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leitgeb A, Wappel J, Slugovc C. Polymer. 2010;51:2927–2946. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Buchmeiser MR. Macromol. Symp. 2010;298:17–24. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sutthasupa S, Shiotsuki M, Sanda F. Polymer J. 2010;42:905–915. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder JB, Raines RT. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:767–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoveyda AH, Malcolmson SJ, Meek SJ, Zhugralin AR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:34–44. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kress S, Blechert S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:4389–4408. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15348c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Fujimura O, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2499–2500. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fujimura O, Grubbs RH. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:824–832. doi: 10.1021/jo971952z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) La DS, Ford JG, Sattely ES, Bonitatebus PJ, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:11603–11604. [Google Scholar]; (d) La DS, Sattely ES, Ford JG, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7767–7778. doi: 10.1021/ja010684q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tsang WCP, Jernelius JA, Cortez GA, Weatherhead GS, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2591–2596. doi: 10.1021/ja021204d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Seiders TJ, Ward DW, Grubbs RH. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3225–3228. doi: 10.1021/ol0165692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Berlin JM, Goldberg SD, Grubbs RH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:7591–7595. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Funk TW, Berlin JM, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1840–1846. doi: 10.1021/ja055994d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Savoie J, Stenne B, Collins SK. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:1826–1832. [Google Scholar]; (e) Stenne B, Timperio J, Savoie J, Dudding T, Collins SK. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2032–2035. doi: 10.1021/ol100511d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Tiede S, Berger A, Schlesiger D, Rost D, Luehl A, Blechert S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:3972–3975. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kannenberg A, Rost D, Eibauer S, Tiede S, Blechert S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:3299–3302. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Van Veldhuizen JJ, Garber SB, Kingsbury JS, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:4954–4955. doi: 10.1021/ja020259c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Van Veldhuizen JJ, Gillingham DG, Garber SB, Kataoka O, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12502–12508. doi: 10.1021/ja0302228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Van Veldhuizen JJ, Campbell JE, Giudici RE, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6877–6882. doi: 10.1021/ja050179j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For an early example of Z-selective ROCM, see Randall ML, Tallarico JA, Snapper ML. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:9610–9611. Tallarico JA, Randall ML, Snapper ML. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:16511–16520.

- 10.(a) Ibrahem I, Yu M, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3844–3845. doi: 10.1021/ja900097n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu M, Ibrahem I, Hasegawa M, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2788–2799. doi: 10.1021/ja210946z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Khan RKM, O'Brien RV, Torker S, Li B, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12774–12779. doi: 10.1021/ja304827a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Khan RKM, Zhugralin AR, Torker S, O'Brien RV, Lombardi PJ, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12438–12441. doi: 10.1021/ja3056722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Endo K, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8525–8527. doi: 10.1021/ja202818v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keitz BK, Endo K, Herbert MB, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9686–9688. doi: 10.1021/ja203488e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Keitz BK, Endo K, Patel PR, Herbert MB, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:693–699. doi: 10.1021/ja210225e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rosebrugh LE, Herbert MB, Marx VM, Keitz BK, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:1276–1279. doi: 10.1021/ja311916m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Absolute configurations were assigned by analogy to that of 9c, which was determined by X-ray crystallography see SI for details.

- 14.Attempts to employ heteroatom-substituted olefins (butyl vinyl ether) resulted in no ROCM product presumably due to catalyst deactivation.

- 15.This assumes that secondary metathesis processes proceed at a negligible rate compared to the productive (ROCM) reaction. Measurements of the formation of 9e (see SI) show that the Z/E ratio is constant during the course of the reaction and for several hours after complete conversion.

- 16.Liu P, Xu X, Dong X, Keitz BK, Herbert MB, Grubbs RH, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1464–1467. doi: 10.1021/ja2108728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.