Abstract

We developed and evaluated a brief (8-session) version of cognitive-behavioral therapy (BCBT) for anxiety disorders in youth ages 6 to 13. This report describes the design and development of the BCBT program and intervention materials (therapist treatment manual and child treatment workbook) and an initial evaluation of child treatment outcomes. Twenty-six children who met diagnostic criteria for a principal anxiety diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and/or social phobia were enrolled. Results suggest that BCBT is a feasible, acceptable, and beneficial treatment for anxious youth. Future research is needed to examine the relative efficacy of BCBT and CBT for child anxiety in a randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: childhood anxiety, anxiety disorders, cognitive behavioral therapy, Coping Cat, brief treatment

Anxiety disorders (AD) are common in youth, with epidemiological studies and large surveys suggesting that approximately 10% to 20% of youth experience impairing anxiety (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003). Current estimates indicate that as many as 50% to 70% of children with disordered levels of anxiety have not received treatment (Chavira, Stein, Bailey, & Stein, 2004; Egger & Burns, 2004). Childhood anxiety disorders that are untreated are associated with significant impairment in school performance, family functioning, and social relationships (e.g., Ialongo, Edelsohn, Werthamer-Larsson, Crockett, & Kellam, 1995). Furthermore, untreated anxiety in youth tends to run a chronic course extending into adulthood (Costello & Angold, 1995; Ferdinand & Verhulst, 1995), putting individuals at increased risk for later psychopathology (e.g., anxiety, depression, substance abuse; Swendsen et al., 2010) and educational underachievement as adults (Woodward & Fergusson, 2001). Given the frequency with which anxiety disorders occur in youth and their associated impairment, researching effective and efficient treatments remains a valued priority (Kendall, Settipani, & Cummings, 2012).

Previous summaries of outcome evaluations of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxious youth have concluded that the treatment is “Probably Efficacious” (APA Task Force on the Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures, 1995; Ollendick & King, 2012; Silverman, Pina, & Viswesvaran, 2008) as multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) by several research groups support its efficacy and the maintenance of gains (Barrett et al., 1996; Barrett, 1998; Beidel, Turner, & Morris, 2000; Kendall et al., 1997; Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008; Manassis et al., 2002; Silverman et al., 1999). The Coping Cat program (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006a, 2006b), one specific CBT protocol for youth anxiety, has been the treatment evaluated in several of the RCTs (e.g., Kendall, Hudson, et al., 2008) including the largest evaluation—a multisite RCT with 488 participants randomized to CBT (Coping Cat), medication (sertraline), combined CBT and medication, and pill placebo conditions (e.g., Walkup et al., 2008). Given the favorable outcomes in recent comparisons with alternate treatments and with both medication and pill placebo, CBT for youth anxiety may be considered an efficacious treatment.

The next step to improving treatment is to improve the efficiency of the treatment and enhance treatment dissemination (Kendall, 2012). By enhancing treatment efficiency, barriers to treatment are addressed. First, it may be more feasible to implement brief cognitive-behavioral therapy (BCBT) in community settings because BCBT requires fewer sessions. Second, BCBT may increase the number of clients for whom a trained therapist could provide services (i.e., 2 clients treated for every 1 client treated with 16-week CBT). Although speculative, it may be easier to train therapists in BCBT because it requires that therapists learn fewer treatment features (training therapists in CBT for anxiety disorders has been identified as a barrier for implementation; Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Beidas, Edmunds, Marcus, & Kendall, 2012). Third, BCBT may be more acceptable to clients because it requires fewer sessions, potentially reducing treatment cost, transportation cost, and time and effort involved. All of these factors lead to treatment attrition in community clinics. Thus, effective BCBT has the potential to reduce the research-to-practice gap that has been identified as a pressing priority for mental health services research (Herschell, McNeil, & McNeil, 2004) and is the next step in the refinement of treatment of anxiety disorders in youth.

CBT for anxious youth is typically comprised of (a) psychoeducation, (b) skill training, including the development of affect recognition, cognitive restructuring, relaxation, and problem solving, and (c) exposure to feared stimuli. Both researchers and clinicians have speculated about which components within treatment programs make the most substantial contributions to treatment gains, but little empirical data are available. Although the literature to date is scant, studies suggest that some treatment components of CBT are especially potent in producing greater therapeutic change, whereas other components may be less essential. Research is critical for determining the critical components of CBT (Damschroder et al., 2009): to date, exposure and cognitive restructuring have been proposed as central.

Exposure is widely viewed as a critical component of CBT for anxiety disorders. In one RCT evaluating a 16-week CBT, assessments were conducted midtreatment (after 8 weeks of education/skills training, but before exposure). Whereas midtreatment comparisons revealed nonsignificant differences between CBT-treated children and waitlist children, comparisons at posttreatment (after the exposure tasks) identified that the treatment produced beneficial gains (Kendall et al., 1997). These results, though not a direct comparison, suggest that exposure tasks are necessary for effective treatment. Similar findings are present in the adult anxiety literature, where it has been found that exposure tasks alone can produce treatment gains that are comparable to exposures coupled with cognitive restructuring (e.g., Bryant, Sackville, Dang, Moulds, & Guthrie, 1999; Hope, Heimberg, & Bruch, 1995). Taken together, these findings support the importance of exposure tasks in the effective treatment of anxiety (Kendall, 2012; Kendall et al., 2005).

Cognitive change has also been suggested as a key ingredient. Two studies evaluated the role of changes in children’s self-talk as a mediator of outcome. Treadwell and Kendall (1996) found that changes in children’s negative self-talk mediated treatment outcome for youth who received a 16-week CBT program. The mediational role of changes in negative self-talk was further examined using a separate sample of treated AD youth and improved methods (Kendall & Treadwell, 2007). The findings from this second study were consistent with the earlier report and suggest that reductions in children’s negative self-talk but not changes in positive self-talk (the “power of non-negative thinking,” Kendall, 1984), mediate treatment response for CBT-treated AD youth. Other potential mediators have yet to be evaluated, so alternate explanations cannot be eliminated. Nevertheless, results suggest that a change in negative self-talk is a mediational model and features of CBT that address self-talk merit retention in a BCBT.

Research suggests that other components of CBT may be less essential for therapeutic change. For example, previous empirical work found that CBT remains effective without extensive progressive muscle relaxation training (e.g., Hudson, 2005; Rapee, 2000). The removal and/or reduction of relaxation training in previous studies was intended to allow treatment to be time- and cost-effective, a goal consistent with developing a BCBT. Other components of CBT have been understudied with regard to their role as critical components (e.g., psychoeducation, skill-building, problem-solving, affect regulation). Given the paucity of literature, we hypothesized that youth may need skill-building to engage with the treatment and the exposure tasks.

In the present study, an 8-session brief CBT program (i.e., therapist manual and client workbook) was developed and evaluated with 26 children (6 to 13 years old) who met criteria for a DSM-IV principal diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), separation anxiety disorder (SAD), or social phobia (SP). The primary aims were to evaluate the feasibility of enrolling, retaining, and treating children with BCBT. Secondary aims included examination of child treatment outcomes and therapist adherence and acceptance of the protocol. We hypothesized that the BCBT program would be feasible to implement, that youth outcomes would improve, and that therapists would be adherent and find the treatment acceptable.

Method

Procedure

The project had two phases. Phase I involved the creation of the BCBT program, including the separate development of the therapist treatment manual (Kendall, Crawley, Benjamin, & Mauro, 2012) and child client workbook (Kendall, Beidas, & Mauro, 2012). In Phase II, the feasibility of implementing the treatment and therapist adherence to the BCBT protocol was evaluated, along with the examination of child treatment outcomes.

Phase I

The BCBT program was based on a research-guided determination of critical and adaptable components (Damschroder et al., 2009). Specifically, an 8-week CBT program (brief Coping Cat program) was developed from the inclusion of empirically supported components in the effective treatment of anxious youth (e.g., exposure tasks, Kendall et al., 2005) and the elimination/reduction of features indicated by research as being less essential (e.g., relaxation training; Hudson, 2005). Where research findings were unavailable, the judgments of experience/expert clinicians were used (e.g., deciding which homework assignments to include/exclude). The initial culling of the content and reduction from 16 to 8 sessions was accomplished by the authors with guidance from experienced clinicians within the anxiety clinic.

Once initial drafts were completed, the BCBT treatment materials were distributed to a panel of CBT experts who reviewed treatment materials and completed a series of questionnaires to evaluate the content and format of each individual session, as well as the anticipated ease of implementation and feasibility of the entire BCBT program. The panel consisted of experts in the fields of psychology and psychiatry, each with extensive experience in the development and evaluation of efficacious treatments for anxious youth. Feedback from the expert panel was integrated and iterative revisions were made. The resulting BCBT treatment program was piloted in Phase II of the study. For detailed discussion of the BCBT treatment, please see Beidas, Mychailsyzn, Podell, and Kendall (in press).

Phase II

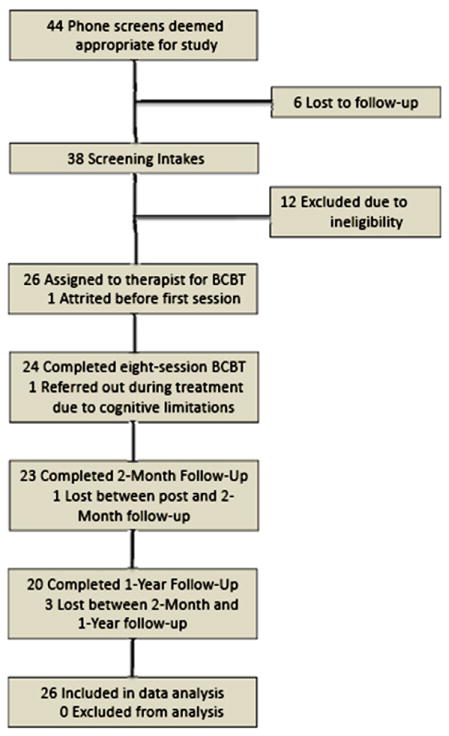

The BCBT program was evaluated using a sample of youth with a principal anxiety diagnosis of SAD, GAD, or SP. Parent(s) participated in a brief telephone screening before being invited to participate in the structured diagnostic interview. Within a week after referral, a clinic staff member contacted the parent(s) to arrange an intake. As indicated by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) table (Figure 1), 38 of 44 children completed the intake assessment. Parents and children were asked to sign informed consent and assent, respectively, for treatment. The protocol was approved by the Temple University Institutional Review Board. Diagnostic interviews and self-report measures were administered separately to the parents and the child at pre- and posttreatment and at 2 months following treatment. A telephone interview was conducted at 1 year following the treatment. In addition, each member of the expert panel reviewed session tapes of a randomly selected case (all sessions; one case per expert) and provided comments and feedback.

Figure 1.

Consort Table.

Participants received 8 therapy sessions (six 1-hour sessions and two 1.5-hour sessions) for a total treatment time of 9 hours (compare to 16 hours). Treatment materials (adapted from the Coping Cat program; Kendall & Hedtke, 2006a, 2006b) included the newly designed therapist manual and child workbook. BCBT sessions focused first on teaching coping skills to the child and/or parent and then on providing the child and/or parent the opportunity to practice the skills via exposure tasks. Therapists served as “coaches” when teaching skills and facilitating practice throughout treatment. Based on experience with manual-based treatments, a flexible implementation consistent with “flexibility within fidelity” was used (see Kendall & Beidas, 2007; Kendall, Gosch, Furr, & Sood, 2008).

Setting and Personnel

During Phase I, devoted to the development of the BCBT program, the expert panel reviewed written treatment materials and provided feedback using rating forms at various points. Following completion of Phase II of the study, the expert panel watched recorded sessions of a randomly selected complete case and provided feedback.

Doctoral students in clinical psychology conducted all structured diagnostic interviews and assessments. BCBT was implemented by eight master’s-level therapists with 2 to 3 years of experience. Therapists participated in weekly 1-hour supervision with the principal investigator throughout the study, which included discussion of cases and review of sessions. All therapists had previously completed CBT training in the 16-week Coping Cat program, studied written manuals, and participated in a full-day workshop prior to initiating supervised pilot cases. The workshop included didactic presentation, role-plays, trainee demonstration, videotape playback, and open discussion. The BCBT protocol was introduced via review of the new manual and workbook in a separate half-day workshop.

Participants

Participants were 26 youths (30.8% female), ages 6 to 13 (M=9.04, SD=2.14), with principal diagnoses of SAD, GAD, or SP enrolled between 2009 and 2010. Children were referred by school personnel, parents, and physicians. Exclusion criteria included the presence of a disabling medical condition, comorbid diagnosis of psychosis or major depressive disorder, mental retardation, or concurrent anxiolitic or antidepressant medication treatment. At least one parent or guardian was required to speak English.

Participants self-identified as Caucasian (n=19; 73.1%), African American (n=1; 3.8%), Asian (n =4; 15.4%), Hispanic (n=1; 3.8%), and “other” (n=1; 3.8%). The sample was moderate to high SES families, and most parents had completed at least some college: Family income was self-reported as below $20,000 (4.8%), up to $40,000 (4.8%), up to $60,000 (14.3%), up to $80,000 (23.8%), and above $80,000 (52.4%). Parents reported education level as high school graduates without college (8.3% of fathers and 8.3% of mothers), some college education (25.0% of fathers and 16.7% of mothers), completed a 4-year college education (37.5% of fathers and 37.5% of mothers), attended graduate school (25.0% of fathers and 33.3% of mothers), or self-identified their education as “other” (4.2% of fathers and 4.2% of mothers).

Principal diagnoses were as follows: Four (15.38%) children were identified with a principal diagnosis of SAD, 6 (23.08%) with SP, 12 (46.15%) with GAD, 3 (11.54%) with both SP and GAD as co-primary, and 1 (3.85%) with both SP and SAD as co-primary. All diagnoses were based on structured interviews (i.e., ADIS). Comorbidity was common: 42.3% of children were comorbid with SAD, 50.0% with SP, 38.5% with GAD, 57.7% with specific phobia, 15.4% with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 7.7% with oppositional defiant disorder, 7.7% with dysthymia, 11.5% with obsessive-compulsive disorder, and 11.5% with school refusal.

Rates of treatment attrition were very low: one participant lost contact between intake assessment and the first therapy session, and another participant was referred out due to cognitive limitations/complications that became apparent during treatment. The 24 remaining participants completed all 8 weekly sessions. One participant was lost to 2-month follow-up, and 3 were lost to 1-year follow-up.

Measures

Treatment Satisfaction

Satisfaction Questionnaire (SQ)

At posttreatment and follow-up, participants and their parent(s) rated 8 SQ items on a 1 to 4 Likert-type scale regarding their own satisfaction with treatment (e.g. “How would you rate the quality of care you have received?”). Items address both negative and positive aspects of the program in a balanced fashion. To help secure unbiased information, this questionnaire was administered by an independent evaluator.

Treatment Integrity

Treatment integrity assessed whether treatment-as-described was treatment-as-provided. A checklist, adapted from that used for the 16-week CBT protocol, measured the integrity of BCBT. All BCBT sessions were videotaped and checked for integrity by the principal investigator and an advanced therapist using a checklist of the content and strategies called for in the sessions. Integrity was checked on 20 randomly selected video-taped sessions (representing all sessions) and therapist adherence to the primary goals and content of the session was rated.

Feasibility

The expert panel completed the following measures following review of the written materials and one videotaped case (all sessions). The BCBT therapists completed these forms after each session for each client.

Summary Therapist Feedback Form (STFF)

At posttreatment, therapists provided feedback about the manual, session content, and workbook. Therapists rated each of the 7 items on a 1-to-7 Likert scale regarding their views on the appropriateness and ease of implementation of the session content and format, as well as the overall feasibility of the treatment program (e.g., “How easy was it to understand the content of the manual?”).

Manual Rating Form (MRF)

During Phase I, the expert panel evaluated the BCBT treatment manual by rating the feasibility and accessibility of (a) each individual session and (b) the entire manual. The 8-item MRF, developed for this project, is rated on a 1 to 7 Likert-type scale with 2 short answer items for additional comments. The data from these forms informed and influenced (i.e., were incorporated into) the content of the BCBT manual, prior to its use in Phase II.

Weekly Therapist Feedback Form (WTFF)

BCBT therapists provided feedback about the treatment manual, session content, and child workbook on a weekly basis. Therapists rated each of the 9 items on a 1 to 7 Likert-type scale regarding their views on the appropriateness and ease of implementation of the session, as well as the feasibility of the treatment program (e.g., “Did you feel rushed to accomplish all of the goals of today’s session?”).

Diagnostic Instruments

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children – Parent (ADIS-P) and Child (ADIS-C) Versions; (Albano & Silverman, 1996; Silverman & Albano, 1996)

This semistructured interview assesses symptoms and severity for DSM-IV diagnoses and permits diagnoses of comorbidity. Good interrater and retest reliability (Silverman & Eisen, 1992) have been reported. Parents and children were interviewed separately. Experienced diagnosticians trained independent raters by observing practice sessions with clients, providing feedback, and assessing performance with reliability assessments. Raters were required to meet and maintain interrater reliability of .85 (Cohen’s κ). All diagnostic interviews were video- and audio-taped. At 1-year follow-up, ADIS interviews using the SAD, GAD, and SP sections were conducted by experienced diagnosticians by phone.

Clinical Global Impression–Severity and Improvement Scales (CGI-S & CGI-I; Guy, 1976)

The CGI-S and CGI-I assessed overall severity and improvement on a 7-point scale, with lower scores indicating less severity and more improvement, respectively. The independent evaluator who conducted the assessment assigned a CGI-S score at pre- and posttreatment, and at 2-month follow-up, and a CGI-I score at posttreatment and 2-month follow-up.

Child Symptomatology

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC-C; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997)

This 39-item self-report scale yields an overall anxiety score and four subscale scores: physical symptoms, social anxiety, harm avoidance, and separation anxiety. Retest reliability ranges from .77 to .88 (March & Albano, 1998; March et al., 1997). The psychometric properties are solid and have been established with multiple samples (e.g., see also Baldwin & Dadds, 2007). A parallel version for parents (MASC-P) to report on their child’s anxiety symptoms was also administered. Both MASC-C and MASC-P were completed at pre- and posttreatment and 2-month follow-up.

Results

Analyses were conducted using (a) the intent-to-treat sample and (b) the completer sample of participants who completed all treatment sessions. Because there were no significant differences, the results reported herein are from the more conservative intent-to-treat analyses.

Acceptability and feasibility were examined via percentages and mean ratings. Treatment acceptability concerned rates of perceived benefit from treatment, whether the program would be recommended to others with similar problems, and parent/child satisfaction with treatment. The feasibility of the intervention was evaluated via rates of recruitment and retention, therapist adherence to the protocol, and feedback from the therapists themselves. Feasibility was also assessed by examining rates of attrition.

Acceptability

Child- and parent-reported satisfaction on the SQ was favorable at both posttreatment and 2-month follow-up (see Table 1). Child and parent ratings were comparable. Both children and parents rated the quality of care that they received as between “excellent” and “good” at posttreatment and 2-month follow-up. Both informants endorsed that “most” to “all” of their needs had been met, they would recommend the program to a friend, they got the help they wanted, they were satisfied with the amount of help they received, and the help they received aided them to deal more effectively with their problems. Overall, they were “mostly satisfied” to “very satisfied” with the help they received, and they reported that they would come back to the clinic if they sought additional services in the future.

Table 1.

Rates of Perceived Benefit From Treatment (Satisfaction Questionnaire)

| Child M (SD) | Range | Parent M (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) How would you rate the quality of care you have received? | ||||

| Post | 1.64 (1.05) | 1–4 | 1.14 (.35) | 1–2 |

| Follow-up | 1.24 (.44) | 1–2 | 1.19 (.40) | 1–2 |

| (2) Did you get the kind of help you wanted? | ||||

| Post | 3.55(.74) | 1–4 | 3.77(.43) | 3–4 |

| Follow-up | 3.64(.66) | 2–4 | 3.62(.50) | 3–4 |

| (3) To what extent has the program met your needs? | ||||

| Post | 1.55(.96) | 1–4 | 1.77(.81) | 1–3 |

| Follow-up | 1.45(.80) | 1–4 | 1.62(.59) | 1–3 |

| (4) If a friend were in need of similar help, would you recommend the program to him/her? | ||||

| Post | 3.82(.50) | 2–4 | 3.91(.29) | 3–4 |

| Follow-up | 3.64(.79) | 1–4 | 3.90(.30) | 3–4 |

| (5) How satisfied are you with the amount of help you have received? | ||||

| Post | 3.55(.74) | 1–4 | 3.64(.49) | 3–4 |

| Follow-up | 3.64(.73) | 1–4 | 3.50(.76) | 3–4 |

| (6) Has the help you have received helped you to deal more effectively with your problems? | ||||

| Post | 1.45(.67) | 1–3 | 1.32(.48) | 1–2 |

| Follow-up | 1.27(.55) | 1–3 | 1.33(.58) | 1–3 |

| (7) In an overall, general sense, how satisfied are you with the help you have received? | ||||

| Post | 1.45 (.74) | 1–4 | 1.27(.46) | 1–2 |

| Follow-up | 1.41 (.73) | 1–4 | 1.29(.46) | 1–2 |

| (8) If you were to seek help again, would you come back to our program? | ||||

| Post | 3.50(.80) | 1–4 | 3.86(.35) | 3–4 |

| Follow-up | 3.36(.95) | 1–4 | 3.76(.44) | 3–4 |

Note. Post=posttreatment; Follow-up=2-month follow-up. Anchors for Likert scale by question were as follows: Question (1) 1=Excellent, 2=Good, 3=Fair, 4=Poor; Questions (2), (4), and (8) 1=No, definitely not, 2=No, not really, 3=Yes, generally, 4=Yes, definitely; Question (3) 1=Almost all of my needs have been met, 2=Most of my needs have been met, 3=Only a few of my needs have been met, 4=None of my needs have been met; Question (5) 1=Quite dissatisfied, 2=Indifferent or mildly dissatisfied, 3=Mostly satisfied, 4=Very satisfied; Question (6) 1=Yes, they helped a great deal, 2=Yes, they helped somewhat, 3=No, they didn’t really help, 4=No, they seemed to make things worse; Question (7) 1=Very satisfied, 2=Mostly satisfied, 3=Indifferent or mildly dissatisfied, 4=Quite dissatisfied.

Feasibility

Participant recruitment and retention rates indicate feasibility with the implementation of the BCBT protocol (see Figure 1). Of the 38 potential participants who completed the intake procedures, 26 (68.42%) met study eligibility criteria and were assigned a therapist. Of these, 24 (92.31%) completed the 8-session treatment and 23 (88.46%) of the 26 completed the treatment and all assessments. Using attrition data from the full 16-session CBT treatment (Kendall & Sugarman, 1997), we estimated BCBT attrition a-priori to be 12%. Our results are consistent with this estimate, suggesting attrition from BCBT is comparable with attrition from a full CBT protocol.

Therapists adhered to the protocol: treatment integrity was very favorable. The data indicate that the treatment described in the therapist manual was indeed the treatment that was provided. The randomly selected video-tapes included all 8 child sessions and both parent meetings. Integrity for both parent meetings was 100% (goals/contents matched the treatment manual). For each of the 8 child sessions the percentages were between 94% to 100%, with 6 of the 8 sessions rated 100% adherent.

Therapists provided ratings of the feasibility of implementation of the BCBT protocol. These ratings were obtained to guide later refinement of the manual following Phase II implementation. The STFF was completed by each therapist for each client following completion of the final (8th treatment session; see Table 2). Therapist ratings on the STFF indicated that therapists viewed the manual as easy to understand, easy to implement as outlined, and user-friendly. Therapists also rated the manual as allowing for enough flexibility, absent of unnecessary elements, and containing the CBT elements they believed were important to be included. Therapists noted that they felt “somewhat” rushed to accomplish all treatment goals in 8 sessions. This feedback was considered during revisions.

Table 2.

Summary Therapist Feedback Form (STFF)

| How easy was it to understand the content of the manual? | |

| M (SD) | 6.71 (.56) |

| How easy was it to conduct the treatment as outlined by the manual? | |

| M (SD) | 5.33 (.86) |

| How user-friendly were the treatment materials (manual, workbook)? | |

| M (SD) | 6.14 (.73) |

| Did the manual allow for enough flexibility? | |

| M (SD) | 5.81 (.68) |

| Did you feel 8 sessions were sufficient to accomplish all of the treatment goals? | |

| M (SD) | 3.57 (1.69) |

| Were there any unnecessary elements included in the manual? | |

| M (SD) | 1.45 (.83) |

| Were there any important elements missing from the manual? | |

| M (SD) | 2.16 (1.61) |

Note. Items rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale where 1=“Not at all,” 4= “Somewhat,” and 7=“Very Much.”

Similar in content to the STFF, the Manual Rating Form (MRF), assessed therapists’ session-by-session ratings of ease of understanding of the manual, clarity of session goals, ability to accomplish session goals in the time allotted, session allowance for flexibility of implementation, sufficiency of information included, overall session contribution to the treatment, absence of unnecessary elements, and presence/absence of necessary treatment components (see Table 3). Overall, sessions were rated favorably with one exception: Session 3 was not rated as favorably as the other sessions. In Session 3 therapists felt there was insufficient time to accomplish the session goals and too much information was included. This feedback informed manual revisions.

Table 3.

Manual Rating Form (MRF)

| Item | Session

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Across sessions | |

| (1) How easy was it to understand the content of this session? | |||||||||

| 6.84(.37) | 6.88(.33) | 6.42(.93) | 6.60(1.22) | 6.80(.41) | 6.83(.38) | 6.88(.34) | 6.87(.34) | 6.74(.37) | |

| (2) How clearly stated were the goals of this session? | |||||||||

| 6.84(.37) | 6.84(.37) | 6.58(.65) | 6.92(.28) | 6.76(.44) | 6.88(.34) | 6.92(.28) | 6.96(.21) | 6.81(.27) | |

| (3) How likely were you to accomplish the goals for this session in the time allotted? | |||||||||

| 5.68(1.60) | 6.32(.80) | 3.63(1.06) | 5.38(1.21) | 6.24(.88) | 6.04(.86) | 6.00(.93) | 5.48(1.34) | 5.64(.56) | |

| (4) How much does the manual allow for flexibility in this session? | |||||||||

| 5.40(1.53) | 5.68(.99) | 4.08(1.10) | 5.25(1.11) | 5.56(1.12) | 5.88(.85) | 5.67(.96) | 5.70(1.11) | 5.31(.72) | |

| (5) How much information did the manual include for this session? | |||||||||

| 4.24(1.13) | 4.20(.58) | 5.75(1.26) | 4.58(1.02) | 4.04(.20) | 4.04(.20) | 4.13(.45) | 4.30(.70) | 4.42(.47) | |

| (6) How much did this session contribute to the manual? | |||||||||

| 5.88(1.60) | 6.36(.86) | 6.42(.78) | 6.42(.93) | 6.40(.91) | 6.58(.78) | 6.58(.72) | 6.61(.72) | 6.39(.65) | |

| (7) Were there unnecessary elements included in this session? | |||||||||

| 1.44(1.08) | 1.24(.61) | 1.00(0) | 1.13(.34) | 1.12(.44) | 1.08(.28) | 1.08(.28) | 1.48(.99) | 1.13(.22) | |

| (8) Were there important elements missing from this session? | |||||||||

| 1.42(1.18) | 2.00(1.76) | 1.58(1.64) | 2.08(1.93) | 1.84(1.57) | 1.46(1.06) | 1.45(1.50) | 1.57(1.27) | 1.80(1.08) | |

Note. Items (1–4) and (6–8) rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale where 1=“Not at all,” 4=“Somewhat,” and 7=“Very Much.” Item (5) rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale where 1=“Too Little,” 4=“Adequate,” and 7=“Too Much.”

Therapists completed the WTFF following each session with each client. WTFF ratings assessed therapist perceptions of the applicability of homework (STIC) tasks, usefulness of the workbook, child mastery of the session content, presence/absence of necessary and unnecessary elements, feeling “rushed” to accomplish treatment goals, adequacy of rapport building time in session, flexibility, and overall session fit within the larger treatment protocol (see Table 4). Similar to the feedback obtained from the MRF, sessions were rated quite favorably. However, Session 3 ratings were discrepant from the otherwise favorable session ratings. Session 3 was rated as difficult to accomplish in the time allotted, containing insufficient time for rapport building, and lacking flexibility. Additionally, therapists expressed less confidence in the child’s mastery of session content from Session 3 compared to other sessions. Therapists concerns about Session 3 in particular, as noted on the WTFF and MRF, guided later revisions of the treatment materials.

Table 4.

Weekly Therapist Feedback Form (WTFF)

| Item | Session

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Across sessions | |

| (1) Did you find the STIC tasks assigned this week useful and applicable for today’s session? | |||||||||

| 6.24(1.03) | 6.60(.71) | 6.38(.92) | 6.63(.71) | 6.44(.82) | 6.46(.72) | 6.46(.75) | 6.35(.83) | 6.45(.57) | |

| (2) Did you find the workbook content useful for today’s session? | |||||||||

| 5.28(1.28) | 5.92(1.53) | 5.96(1.20) | 5.04(1.68) | 4.56(1.56) | 4.54(1.35) | 4.79(1.47) | 4.61(1.20) | 5.08(.99) | |

| (3) Did you feel the child was able to master the information presented in the session? | |||||||||

| 5.08(1.71) | 5.48(1.23) | 4.33(1.37) | 5.00(1.47) | 5.28(1.28) | 5.17(1.49) | 5.17(1.58) | 5.26(1.36) | 5.10(1.06) | |

| (4) Were there unnecessary elements included in this session? | |||||||||

| 1.60(1.12) | 1.72(1.46) | 1.25(.53) | 1.20(.50) | 1.24(.52) | 1.13(.34) | 1.17(.38) | 1.43(1.12) | 1.34(.52) | |

| (5) Were there important elements missing from this session? | |||||||||

| 1.58(1.10) | 1.56(1.08) | 1.26(.75) | 2.08(1.79) | 1.54(1.14) | 1.39(.94) | 1.29(.86) | 1.50(1.34) | 1.58(.86) | |

| (6) Did you feel rushed to accomplish all of the goals of today’s session? | |||||||||

| 3.24(1.36) | 2.08(1.63) | 5.75(1.11) | 3.68(1.57) | 2.76(1.81) | 2.54(1.69) | 3.00(1.98) | 3.35(1.92) | 3.32(1.06) | |

| (7) How adequate was the amount of time allotted for today’s session to build and maintain rapport? | |||||||||

| 5.44(1.19) | 6.29(.86) | 3.42(1.38) | 5.04(1.54) | 5.52(1.45) | 5.63(1.38) | 5.29(1.81) | 5.04(1.69) | 5.19(.95) | |

| (8) How much did the manual allow for flexibility in today’s session? | |||||||||

| 5.52(.92) | 5.32(.90) | 4.13(.90) | 5.40(1.12) | 5.80(1.00) | 6.00(.88) | 5.79(.88) | 5.52(1.10) | 5.42(.59) | |

| (9) How well did today’s session fit within the treatment? | |||||||||

| 6.72(.54) | 6.68(.63) | 6.67(.64) | 6.84(.37) | 6.68(.48) | 6.71(.55) | 6.54(.80) | 6.65(.57) | 6.70(.44) | |

Note. Items (1), (4–6), and (8–9) rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale where 1=“Not at all,” 4=“Somewhat,” and 7=“Very Much.” Item (2) rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale where 1=“Not Useful,” 4=“Somewhat Useful,” and 7=“Very Useful.” Item (3) rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale where 1=“No Mastery,”4=“Some Mastery,” and 7=“Excellent Mastery.” Item (7) rated on a 1 to 7 Likert scale where 1=“Not Adequate,” 4=“Somewhat Adequate,” and 7=“Very Adequate.”

Improvement in Anxiety

Improvement in anxiety, measured in several ways by the ADIS-C/P, was based on (a) diagnoses and (b) clinician severity ratings (CSR) scores assigned by reliable independent evaluators. Analyses examined (a) the percentage of children who no longer met diagnostic criteria for their principal pretreatment anxiety diagnosis and (b) changes in the CSR scores for their principal anxiety diagnosis. Outcomes were also evaluated using CGI-I scores at posttreatment (i.e., an independent evaluator CGI-I rating of 1 or 2, indicated a favorable treatment response). Changes in baseline scores on the primary and secondary scalar outcome measures were analyzed using a paired-sample t-test. Analyses also explored potential correlates of treatment outcome, including participant characteristics and scores on pretreatment variables. These variables were examined in relation to scores reflecting both improvement (pre- to posttreatment) and maintenance (pretreatment to 2-month follow-up).

Using composite diagnoses from the ADIS-C/P, 42.3% of BCBT-treated youth no longer met criteria for their principal anxiety diagnosis at posttreatment, 33.3% of these youth did not meet criteria for their principal anxiety diagnosis at the 2-month follow-up period, and 65.0% of these youth did not meet criteria for their principal anxiety diagnosis at the 1-year follow-up period. Examination of mean change in CSR score from pre- to posttreatment evidenced improvement (M=2.0, SD=2.0). Gains were maintained at 2-month follow-up (M=1.90, SD=2.00) and at 1-year follow-up (M=3.45, SD=2.33). Using a paired samples t-test, the CSR score of the principal diagnosis improved significantly from pre- to posttreatment, t = 5.07 (25), p <.001, Cohen’s d = 1.47, from pretreatment to 2-month follow-up, t=4.37 (20), p<.001, Cohen’s d=1.32, and from pretreatment to 1-year follow-up, t=6.63 (19), p<.001, Cohen’s d=1.99. CSR scores of the principal diagnosis also improved significantly from posttreatment to 1-year follow-up, t=3.68 (19), p=.002, Cohen’s d=0.59.

Improvement was also evidenced by mean CGI-I scores at posttreatment (M=2.15, SD=.67) and 2-month follow-up (M=2.35, SD=1.09). Severity, assessed by the CGI-S, was comparable at posttreatment (M = 3.4, SD = 1.19) and 2-month follow-up (M = 3.30, SD = 1.49). CGI-S ratings improved significantly from pre- to posttreatment, t=3.22 (17), p=.005, Cohen’s d=1.56, and from pretreatment to 2-month follow-up, t=2.96 (20), p=.008, Cohen’s d=1.32.

Child ratings of anxiety (MASC-C total score) improved significantly from pre- to posttreatment, t=4.07 (21), p = .001, Cohen’s d = 1.78, and from pretreatment to 2-month follow-up, t=3.75 (21), p=.001, Cohen’s d=1.64. Similarly, parent report of child anxiety symptoms on the MASC-P (total score) improved significantly from pre- to posttreatment, t=4.30 (19), p<.001, Cohen’s d=1.97, and from pretreatment to 2-month follow-up, t=4.84 (18), p<.001, Cohen’s d=2.28. All effect sizes reported above were large effects.

Features of the participants (i.e., child age, household income, parent age) and pretreatment CGI-S scores were not significantly correlated with improvement on the CGI-I. Mean CSR changes from pre-to posttreatment were not significantly associated with child pretreatment primary anxiety diagnosis, χ2 =22.24 (24), p=.565, nor were mean changes from posttreatment to 2-month follow-up, χ2 = 27.18 (20), p=.13. However, from pretreatment to 1-year follow-up CSR changes were significantly associated with child pretreatment primary anxiety diagnosis, χ2=42.27 (28), p=.041. Mean principal diagnosis CSR changes from pre- to posttreatment, pretreatment to 2-month follow-up, and pretreatment to 1-year follow-up respectively by diagnosis were: SAD (M=2.50; M=2.67; M=4.00), SP (M=.83; M=.67; M=.80), GAD (M=2.58; M=1.89; M=4.3), SP and GAD co-primary (M=1.00; M=1.50; M=4.0), and SP and SAD co-primary (M=4.00; M=3.00; M=6.0).

At 1-year follow-up the following percentage of parents reported BCBT components as “very helpful” or “helpful” in reducing anxiety their child’s anxiety: using relaxation skills (85%); changing unhelpful thoughts (90%); using problem-solving skills (95%); parents changing parenting approach (75%); doing exposures (100%); positive relationship with his/her therapist (100%); getting support/help from teachers (65%).

At 1-year follow-up, parents reported potential impediments to improvement as “very much” or “somewhat.” Lack of connection with his/her therapist (5%); avoiding things that make him/her anxious (65%); thinking in very negative ways (45%); difficulty practicing what s/he learned in therapy (60%); difficulty applying what s/he learned in therapy to new situations (35%); having negative things happen to him/her (10%); parental or family member anxiety or other problems (10%); lack of support from family or teachers (10%); being bullied by peers (20%); using drugs or alcohol (0%). At 1-year follow-up 45.0% of parents reported that they did not seek additional services for treating their child’s anxiety after participating in BCBT, and 36.8% of families received additional treatment at the clinic following BCBT. Pretreatment CSR scores of the principal anxiety disorder were not significantly associated with seeking additional treatment following BCBT, χ2 =2.49 (3), p=.48.

Discussion

An 8-session CBT (BCBT; brief Coping Cat program) for anxiety disorders in 6- to 13-year-old youth was developed and evaluated and found to be feasible, acceptable, and beneficial. The streamlined CBT (i.e., BCBT) kept the essential elements, treatment strategies, and sequence of sessions of the 16-session Coping Cat program (Kendall & Hedtke, 2006a, 2006b). The BCBT program was guided by both an expert panel and therapist feedback and relied heavily on findings that highlight the importance of exposure tasks for the effective treatment of anxious youth.

The present findings indicate that a less expansive psychoeducation and a more circumscribed yet direct use of exposure tasks (the BCBT program) were both acceptable and feasible to the participants and to the therapists. The quality of care was reported by parents and children to be sufficient to meet their needs and they reported being satisfied. Consistent with the self-reported outcomes, recruitment and attrition rates were favorable and comparable to those reported for the 16-session CBT (Kendall & Sugarman, 1997). Therapists gave positive reviews of the therapy materials, yet did report feeling “somewhat rushed” to accomplish all the treatment goals in 8 sessions. This finding could be linked to the fact that therapists in the study had been experienced in the 16-session protocol and, not surprisingly, would compare that protocol to the BCBT program.

It was clear that therapists in the study experienced Session 3 of BCBT as having too much content. Such findings highlight the need to weigh the amount of content when implementing manual-based treatment—a notion that has been referred to as “flexibility within fidelity” (Kendall & Beidas, 2007). Just as having too little content in nondirective therapies was insufficient for treating anxiety, having too much content may be unfavorable. Further exploration of session content and the experience of it by participants might facilitate an optimal balance of a BCBT intervention.

The BCBT initial outcomes are promising. Although the sample was limited in socioeconomic and ethnic diversity, 42.3% of youth no longer met criteria for their principal anxiety diagnosis after 8 weeks and 33.3% of youth maintained these gains at a 2-month follow up. When examining principal diagnosis CSRs, there was significant improvement from pretreatment to posttreatment, to 2-month follow-up. Research on abbreviated treatment of specific phobias in children also found that treatment gains improved over time (Ollendick et al., 2009). Many factors could explain the treatment gain over time. Importantly, immediately following treatment, youth have less experience practicing their skills independently, which may explain the gradual improvement over time.

At 1-year follow-up, 65.0% of youth no longer met criteria for their principal anxiety diagnosis, though 55% of participants reported seeking additional treatment. When examining principal diagnosis CSRs, there was significant improvement from pretreatment to 1-year follow-up. The reasons for seeking additional treatment are unknown, but one possibility is that participants required additional booster sessions as a result of the abbreviated length of treatment. Participants might benefit from one or more scheduled booster sessions following completion of BCBT.

When assessed at 1-year follow-up, principal diagnosis CSR reductions (from pretreatment) varied significantly by diagnosis. That is, youth with social phobia as a principal diagnosis were less likely to show additional treatment gains at 1-year follow-up, whereas other youth demonstrated increased treatment giants at 1-year follow-up. It should be noted that 1-year follow-up assessments were conducted over the phone, which could have influenced these results. This finding is consistent with research from Puleo, Read, Klugman, and Kendall (2012), who found that youth with social phobia evidenced reduced maintenance of long-term gains.

Child self-reported anxiety also showed significant improvement. Though a direct RCT comparison is needed, a first blush consideration of the present results indicate beneficial gains for a reasonable percentage of cases. Within the next needed study—an RCT comparison of the 16-session CBT with the BCB—would be the search for predictors that identify who would benefit from BCBT and who would need the longer intervention.

Despite the high prevalence rates for anxiety disorders in youth, surveys indicate that these children are not being treated and although CBT for anxious youth is the recommended treatment, most anxious youth are not receiving this treatment. It is important to find interventions that are not only efficacious, but also cost-efficient and effective in routine clinical care settings. A recent study compared usual care (UC) and CBT in a community mental health clinic (Southam-Gerow et al., 2010). Surprisingly, although children benefitted, CBT did not outperform UC, but there is more to the story. Those in UC also received significantly more other intervention services and only 52% of CBT youth received a full dose of CBT. More than 40% of CBT youth did not receive exposure tasks, a critical component of CBT. One conclusion could be that CBT did not outperform UC, but another conclusion would be CBT was provided in a diluted (e.g., lacking exposures) form. CBT is not simply having a client “taking deep breaths” or being encouraged to engage in “positive thinking.” One could ask, “Is it CBT if the exposures are missing?” and the answer would be “no.” The present BCBT, which includes exposure tasks, may be more readily disseminated because it is a time-efficient program; however, it will be essential, again, that exposure tasks—challenging exposure tasks—be included/delivered before the program is deemed CBT.

In this open pilot, BCBT was tested on moderate to upper SES youth who are primarily Caucasian; additional study is warranted to determine its efficacy on more diverse populations of youth. Additionally, research on the implementation of BCBT by community clinicians is needed to determine whether they find BCBT and its focus on exposure tasks to be feasible and acceptable. Feedback from this research will inform whether the treatment protocol needs to be further reformed.

BCBT could be a valuable resource in primary care and school settings. Schools offer a promising setting because underserved anxious children are in need of treatment and could circumvent barriers to accessing outpatient services (Mychailyszyn, Brodman, Read, & Kendall, in press). A school-based program also offers an environment where BCBT could flourish given its short duration, access to both anxious and at-risk youth, and the availability to provide experiential learning via in vivo exposures may be optimal.

The present study has limitations. The evaluation of feasibility and acceptability was less hampered, but the evaluation of outcomes did not have a comparison condition. As a result, multiple sources of invalidity (e.g., attention, passage of time) could help explain the changes. Also, some of the measures used were developed for the present study and psychometric information is limited. Therapists utilized in this study were experienced in the delivery of CBT for anxious youth. Additional research conducted with inexperienced clinicians is needed in that experienced clinicians may present BCBT differently because they may have a more difficult time adapting their treatment style to the abbreviated time period or may have better treatment outcomes due to their experience. Finally, youth in this study were allowed to seek additional treatment services between 2-month and 1-year follow-up. Future research should examine whether this further treatment is warranted, and if so, identify which children will need continued therapeutic services.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH grant (MH080788) to Philip C. Kendall. We thank our outside expert reviewers (Drs. Anne Marie Albano, Christian Mauro, John Piacentini, Wendy Silverman, John Walkup) for their valuable input.

Contributor Information

Sarah A. Crawley, Kennedy Krieger Institute/Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Philip C. Kendall, Temple University

Courtney L. Benjamin, Temple University

Douglas M. Brodman, Temple University

Chiaying Wei, Temple University.

Rinad S. Beidas, University of Pennsylvania

Jennifer L. Podell, University of California, Los Angeles

Christian Mauro, Duke University.

References

- Albano AM, Silverman WK. Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child Version. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. Clinician Manual for the Anxiety Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- APA Task Force on the Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures. Training in and dissemination of empirically-validated psychological treatments: Report and recommendations. Clinical Psychologist. 1995;48:3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JS, Dadds MR. Reliability and validity of parent and child versions of the multidimensional anxiety scale for children in community samples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:252–260. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246065.93200.a1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000246065.93200.al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PM. Evaluation of cognitive-behavioral group treatments for childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:459–468. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2704_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P, Dadds M, Rapee R. Family treatment of childhood anxiety: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:333–342. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Edmunds JM, Marcus SC, Kendall PC. Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services. 2012 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100401. Epub ahead of print retrieved July 12, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17:1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. http://dx.doi.org/1001111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas R, Mychailsyzn M, Podell J, Kendall P. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for anxious youth: The inner workings. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.07.004. (in press) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. Behavioral treatment of childhood social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:1072–1080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Sackville T, Dang ST, Moulds M, Guthrie R. Treating acute stress disorder: An evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy and supporting counseling techniques. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:1780–1786. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.11.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey K, Stein MT. Child anxiety in primary care: Prevalent but untreated. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:155–164. doi: 10.1002/da.20039. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/da.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Angold A. Epidemiology. In: March JS, editor. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford; 1995. pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Burns BJ. Anxiety disorders and access to mental health services. In: Ollendick TH, March JS, editors. Phobic and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 530–549. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC. Psychopathology from adolescence into young adulthood: An 8-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1586–1594. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. The ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology-Revised. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, Mental Health Administration, NIMH Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research; 1976. The clinical global impression scale; pp. 218–222. DHEW Publ No ADM 76–338. [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, McNeil CB, McNeil DW. Clinical child psychology’s progress in disseminating empirically supported treatments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Bruch MA. Dismantling cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:637–650. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00013-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL. Mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy for anxious youth. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo N, Edelsohn G, Werthamer-Larsson L, Crockett L, Kellam S. The significance of self-reported anxious symptoms in first grade children: Prediction to anxious symptoms and adaptive functioning in fifth grade. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01300.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.ep11520744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Behavioral assessment and methodology. In: Wilson G, Franks C, Brownell K, Kendall PC, editors. Annual review of behavior therapy: Theory and practice. Vol. 9. New York, NY: Guilford; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC. Treating anxiety in youth. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. 4. New York, NY: Guilford; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Beidas RS. Smoothing the trail for dissemination of evidence-based practices for youth: Flexibility within fidelity. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38:13–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.1.13. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Beidas RS, Mauro C. Brief Coping Cat: The 8-session Coping Cat workbook. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Crawley S, Benjamin C, Mauro C. Brief Coping Cat: The 8-session therapist manual. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Flannery-Shroeder E, Panichelli-Mendel S, Southam-Gerow M, Henin A, Warman MJ. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: A second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Gosch E, Furr J, Sood E. Flexibility within fidelity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:987–993. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed2f. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hedtke K. Coping Cat Workbook. 2. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006a. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hedtke K. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxious children: Therapist manual. 3. Ardmore, PA: Workbook Publishing; 2006b. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Robin JA, Hedtke KA, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Conducting CBT with anxious youth? Think exposures. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:136–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Settipani C, Cummings C. No need to worry: The promising future of child anxiety research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:103–115. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.632352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Sugarman A. Attrition in the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:883–888. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Treadwell K. The role of self-statements as a mediator in treatment for anxiety-disordered youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:380–389. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manassis K, Mendlowitz SL, Scapillato D, Avery D, Fiksenbaum L, Freire M, Owens M. Group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:1423–1430. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Albano AM. Advances in the assessment of pediatric anxiety disorders. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;20:213–241. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker J, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners C. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mychailyszyn MP, Brodman DM, Read KL, Kendall PC. Cognitive-behavioral school-based interventions for anxious and depressed youth: A meta-analysis of outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick T, King N. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Issues and commentary. In: Kendall PC, editor. Child and adolescent therapy: Cognitive-behavioral procedures. 4. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Ost LG, Reuterskiold L, Costa N, Cederlund R, Sirbu C, Jarrett MA. One-session treatment of specific phobias in youth: A randomized clinical trial in the United States and Sweden. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:504–516. doi: 10.1037/a0015158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puleo CM, Read KL, Klugman J, Kendall PC. Cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with social phobia: Differential short and long term treatment outcomes. 2012. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. Group treatment of children with anxiety disorders: Outcome and predictors of treatment response. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2000;52:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (DSM-IV) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Eisen A. Age differences in the reliability of parent and child reports of child anxious symptomatology using a structured interview. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:117–124. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W, Kurtines W, Ginsburg G, Weems C, Rabian B, Serafini L. Contingency management, self-control, and education support in the treatment of childhood phobic disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:675–687. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Pina A, Viswesvaran C. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents: A ten year update. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:105–130. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow M, Weisz J, Chu B, McLeod B, Gordis E, Connor-Smith J. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety outperform usual care in community clinics? An initial effectiveness test. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen J, Conway KP, Degenhardt L, Glantz M, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Kessler R. Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse, and dependence: Results from the 10-year survey follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction. 2010;105:1117–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadwell KRH, Kendall PC. Self-talk in anxiety-disordered youth: States-of-mind, content specificity, and treatment outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:941–950. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Ginsburg GS, Kendall PK. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM. Life course outcomes of young people with anxiety disorders in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1086–1093. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200109000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]