Abstract

Tissue engineering applications commonly encompass the use of three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds to provide a suitable microenvironment for the incorporation of cells or growth factors to regenerate damaged tissues or organs. These scaffolds serve to mimic the actual in vivo microenvironment where cells interact and behave according to the mechanical cues obtained from the surrounding 3D environment. Hence, the material properties of the scaffolds are vital in determining cellular response and fate. These 3D scaffolds are generally highly porous with interconnected pore networks to facilitate nutrient and oxygen diffusion and waste removal. This review focuses on the various fabrication techniques (e.g., conventional and rapid prototyping methods) that have been employed to fabricate 3D scaffolds of different pore sizes and porosity. The different pore size and porosity measurement methods will also be discussed. Scaffolds with graded porosity have also been studied for their ability to better represent the actual in vivo situation where cells are exposed to layers of different tissues with varying properties. In addition, the ability of pore size and porosity of scaffolds to direct cellular responses and alter the mechanical properties of scaffolds will be reviewed, followed by a look at nature's own scaffold, the extracellular matrix. Overall, the limitations of current scaffold fabrication approaches for tissue engineering applications and some novel and promising alternatives will be highlighted.

Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds are commonly used for drug delivery,1,2 investigation of cell behavior and material studies in the field of tissue engineering.3–5 Three-dimensional scaffolds are typically porous, biocompatible and biodegradable materials that serve to provide suitable microenvironments, that is, mechanical support, physical, and biochemical stimuli for optimal cell growth and function (Fig. 1).6–9 The porosity and pore size of 3D scaffolds have direct implications on their functionality during biomedical applications. Open porous and interconnected networks are essential for cell nutrition, proliferation, and migration for tissue vascularization and formation of new tissues (Fig. 2).6,7,10 A porous surface also serves to facilitate mechanical interlocking between the scaffolds and surrounding tissue to improve the mechanical stability of the implant.11 In addition, the network structure of the pores assists in guiding and promoting new tissue formation.9,12 Materials with high porosity enable effective release of biofactors such as proteins, genes, or cells and provide good substrates for nutrient exchange. However, the mechanical property that is important in maintaining the structural stability of the biomaterial is often compromised as the result of increased porosity.7 Hence, a balance between the mechanical and mass transport function of the scaffolds should exist for an optimal scaffold system. As a result, the final porosity and pore sizes of the scaffold should be taken into account in accordance to the intended eventual application during scaffold design and fabrication stages. This review is focused on the fabrication of porous 3D scaffolds, the methods for evaluating porosity and pore sizes of 3D constructs, and some of the reported effects of pore size and porosity on cell behavior and overall mechanical properties. A more general overview of the various scaffold fabrication and porosity measurement techniques has been covered in previous reviews.11,13–15

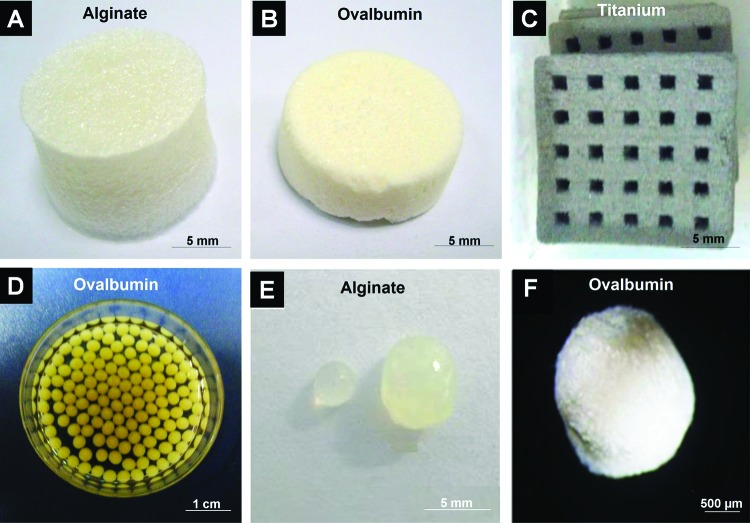

FIG. 1.

Images of three-dimensional (3D) (A–C) scaffolds, (D, E) hydrogels, and (F) microcarriers of various geometry, size and morphology used in tissue engineering applications. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

FIG. 2.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of (A, B) porous scaffolds and (C, D) human tissues with interconnected pores. Tissue engineered scaffolds should ideally mimic the porosity, pore size, and function of native human tissues.

Fabrication of 3D Porous Scaffolds

Various techniques have been used for the fabrication of 3D scaffolds. Generally, conventional fabrication techniques such as salt leaching, gas forming, phase separation, and freeze-drying (Fig. 3) do not enable precise control of internal scaffold architecture or the fabrication of complex architectures that could be achieved by rapid prototyping techniques (Fig. 4) using computer-aided design (CAD) modeling.8 These conventional techniques also require good fabrication skills to maintain consistency in scaffold architecture. Another limitation present is the use of toxic solvents, which may result in cell death if they are not completely removed.16 Besides, scaffolds fabricated using these traditional processing techniques have compressive moduli at a maximum of 0.4 MPa, which is much lower than hard tissue (10–1500 MPa) or most soft tissues (0.4–350 MPa).7,17 Hence, the development of rapid prototyping fabrication techniques enables the fabrication of scaffolds with improved mechanical properties, with moduli ranging from soft to hard tissues.18,19 Conversely, rapid prototyping techniques have better design repeatability, part consistency, and control of scaffolds architecture at both micro and macro levels.16,20,21 Although rapid prototyping techniques may have several advantages, some limitations and challenges still remain such as the limited number of biomaterials that can be processed by rapid prototyping compared to conventional techniques.22 Other approaches that mimic the way that tissues are formed in the body, and their nanofibrous structure can be found in modular assembly methods, and electrospinning methods.23–26 Alternative approaches to prefabrication of scaffolds prior to cell seeding include cell encapsulation, and the development of tunable scaffolds that have the potential for further modification postimplantation. The advantages and disadvantages of these alternative approaches will also be discussed in this section.

FIG. 3.

Schematic illustrations of some conventional fabrication methods: (A) gas foaming/particulate leaching, (B) thermally induced phase separation, and (C) electrospinning used to obtain porous scaffolds. Images adapted and reproduced by permission of Elsevier and The Royal Society of Chemistry (http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C2JM31290E).27–29 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

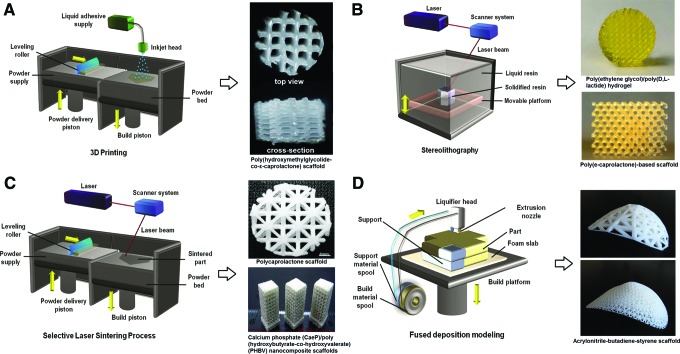

FIG. 4.

Schematic illustrations and images of 3D scaffolds fabricated from rapid prototyping methods: (A) 3D printing, (B) selective laser sintering, (C) stereolithography, and (D) fused deposition modeling. Images adapted and reproduced by permission of Elsevier.30–35 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Salt leaching

This method has been commonly used to fabricate scaffolds for tissue engineering applications.14,36,37 Using this method, porogen or salt crystals (e.g., sodium chloride) are placed into a mold and a polymer is then added to fill in the remaining spaces. The polymer is subsequently hardened and the salt is removed via dissolution in a solvent such as water or alcohol. A hardened polymer with pores will be formed once all the salt leaches out.38 The pore size of the scaffolds can be controlled by the size of porogen used. The porosity and pore size of the scaffold can also be controlled by varying the amount and size of the salt particles respectively.14 The main advantage of this technique is the use of small amounts of polymer, which minimizes any polymer wastage unlike those methods that require large machinery and produces unused material parts during fabrication such as some of the rapid prototyping techniques. However, the interpore openings and pore shape of scaffolds produced by this method is not controllable.14 Thus, by combining salt leaching with other scaffold fabrication techniques, it may be possible to create scaffolds with better pore interconnectivity and structure.39

Gas forming

In this technique, gas is used as a porogen.40 Solid discs of polymers such as polyglycolide and poly-L-lactide are first formed by compression molding at high temperatures prior to the application of high-pressure carbon dioxide gas through the discs for a few days before reducing the pressure back to atmospheric level.41 The main advantage of using this method is the elimination of the use of harsh chemical solvents, thus removing the leaching step from the fabrication process, which subsequently reduces the overall fabrication time. However, it is difficult to ensure pore connectivity and control of the pore sizes by gas forming.42,43 Further, the application of high temperatures during disc formation also prohibits the use of bioactive molecules in the scaffolds.44 With this gas forming technique, scaffolds with porosity up to 93% and pore sizes up to 100 μm can be fabricated.44

Phase separation

In general, a polymer is first dissolved in a suitable solvent and subsequently placed in a mold that will be rapidly cooled until the solvent freezes. The solvent is then removed by freeze-drying and pores will be left behind in the polymer. This method also does not necessitate an extra leaching step, but the addition of organic solvents such as ethanol or methanol inhibits the incorporation of bioactive molecules or cells during scaffold fabrication. In addition, the small pore sizes obtained is another limiting factor of scaffolds fabricated by phase separation.14,44 Different types of phase separation techniques available include thermally-induced, solid-liquid, and liquid–liquid phase separation.45–47

Freeze-drying

When materials are freeze-dried, the frozen water is sublimated directly into the gas phase, which results in pore formation.48 This method was first used by Whang et al. to fabricate PLGA scaffolds.49 The porosity and pore sizes of the scaffolds fabricated are largely dependent on the parameters such as ratio of water to polymer solution and viscosity of the emulsion.44 The pore structure of the scaffolds can be controlled by varying the freezing temperature.50 The advantages of this process are the elimination of several rinsing steps since dispersed water and polymer solvents can be removed directly.49 Moreover, polymer solutions can be used directly, instead of the need to cross-link any monomers. However, the freeze-drying process should be controlled to reduce heterogeneous freezing to increase scaffold homogeneity.50

3D printing

Three-dimensional printing involves the laying down of successive layers of material to form 3D models, thus enabling better control of pore sizes, pore morphology, and porosity of matrix as compared with other fabrication methods.7,51 In general, the binder solution is added onto the powder bed from an “inkjet” print head. A 2D layer will be printed and a new layer of powder will be laid down subsequently. The process repeats and the layers will merge when fresh binder solution is deposited each time. The finished component will be removed and any unbound powder will be left behind. This technique allows more complex 3D shapes with high resolution and controlled internal structures to be fabricated.52 There are two types of pores fabricated by this process, that is, pore by design and pore by process. However, only a limited number of polymers can be fabricated using this method given the high temperatures involved in this method. In addition, ceramic scaffolds obtained by this method have better mechanical strengths, but require a second sintering process at high temperatures to improve on the brittle toughness. Moreover, preprocessing of base biomaterials is necessary as they are usually not in powdered form.53,54

Selective laser sintering

In the selective laser sintering (SLS) process, regions on the powder bed are fused layer by layer using a computer controlled laser beam to form a 3D solid mass.55–57 Due to the stepwise addition of materials, SLS enables the construction of scaffolds with complex geometries. Moreover, any powdered biomaterial that will fuse but not decompose under a laser beam can be used in this fabrication process. SLS is fast, cost effective and does not require the use of any organic solvents.58 However, the elevated temperatures needed require high local energy input. In addition, degradation of the material, for example, chain scission, cross-linking, and oxidation processes may occur due to exposure to the laser beam.59

Stereolithography

This is one of the earliest rapid prototyping techniques and it involves the use of ultraviolet laser to polymerize liquid ultraviolet curable photopolymer resin layer-by-layer, which then solidifies to form a 3D model.60 The excess resin will be drained after the complete model is raised out of the vat for curing in an oven. This rapid prototyping technique allows quick fabrication of materials with a wide variety of shapes. The resolution of each layer is dependent on the resolution of the elevator layer and the spot size of the laser.61 However, due to the application of additional curing step to improve the model's property, the final resolution is compromised of shrinkage that typically occurs in this postprocessing step.62,63 Also, there is a limited variety of photopolymerisable materials that are suitable for biomedical applications.

Fused deposition modeling

In fused deposition modeling, a small temperature controlled extruder is used to allow thermoplastic material to be deposited onto a platform in a layer by layer manner to form a 3D material.64–66 The base platform will be lowered at the end of each layer so that subsequent layers can then be added onto them. Like the other rapid prototyping methods, fused deposition modeling makes use of computer generated solid or surface models to enable precise deposition of thin layers of the semi-molten polymer. However, the disadvantage of this method is the use of elevated temperatures, which limits the type of biomaterials that can be used.

Electrospinning

During solution electrospinning, a voltage is applied to generate a potential difference between a polymeric solution and a collecting target.67,68 A polymeric jet of fluid will be ejected from a spinneret or tip of a capillary when the surface tension of the fluid is overcomed by the electrical charges. The macromolecular entanglements present in the polymeric solution will cause the fluid jet to be drawn toward the collector as it does not go through Rayleigh instabilities, that is, formation of droplets due to breaking up of the fluid jet.67 As the fluid jet approaches the collector, twisting occurs due to the presence of higher surface charge density. Ultimately, a mesh of electrospun fibers will be collected. The diameter of each fiber can be controlled by altering the concentration and flow rate of the polymer solution, and varying the distance between the needle and collector.68,69 Pham et al. showed that the average pore size of electrospun scaffolds increased with increasing fiber diameter.70 Some advantages of electrospun scaffolds include the presence of high surface area for cell attachment and high porosity to facilitate nutrient and waste exchange.71–73 Solution electrospinning is also a simple and inexpensive scaffold fabrication technique, and a wide range of polymeric solutions can be used to fabricate the scaffolds. However, the main disadvantage of electrospinning is the involvement of toxic organic solvents during fabrication, which can be harmful to cells.74 Thus, melt electrospinning, which does not involve the use of organic solvents, is an alternative to solution electrospinning.75,76 In melt electrospinning, the polymer is heated with an electric heater or CO2 laser above its melting or glass transition temperature.77,78 However, as polymer melts have lower charge density and are more viscous than its solution, fibers obtained from melt electrospinning process are thicker than those fabricated from solution electrospinning.75,79

Cell encapsulation

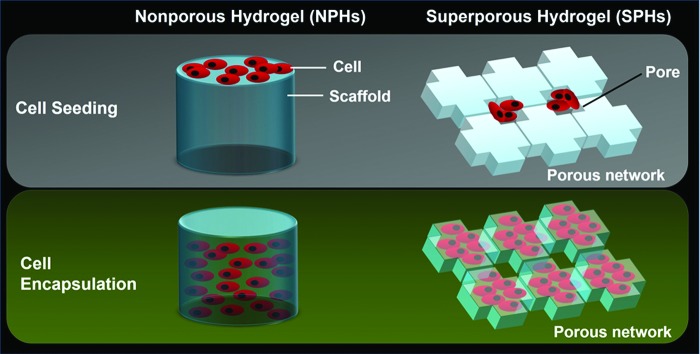

Instead of prefabricating porous scaffolds and culturing cells on them subsequently, an alternative is to incorporate cells during the scaffold fabrication process. Cell encapsulation, involving entrapping cells inside a material, has been commonly used to protect cells from the immune system.80 Generally, cells are mixed with the encapsulation material before gelation occurs. Hence, the encapsulation material and gelation process need to be cytocompatible.81 Reviews by Hunt & Grover and Nicodemus & Bryant discussed some of the materials commonly used for cell encapsulation.82,83 Using this method, cells can either be individually encapsulated or a fixed number of cells can be enclosed in a certain volume of material, in spherical or fiber forms.84–86 Currently, the main limitation of cell encapsulation is the balance between appropriate diffusion coefficient for the transport of oxygen and nutrients to the cells and to the retention of immunoprotective properties.87 However, it has been shown by our group and others that processing conditions, the use of a coating layer, can play a role in modifying the porosity or permeability of the encapsulation material.88–90 Others have used superporous hydrogels (SPHs) instead of nonporous hydrogels (NPHs) as their encapsulation material to facilitate more favorable diffusion properties.42 SPHs have an internal pore architecture that allow cell attachment and proliferation following cell seeding. Conversely, if cells were seeded onto the NPHs, they will only attach onto the surface due to the absence of an internal pore architecture. For cell encapsulation, cells will generally spread throughout the NPHs, but will only be present inside the interpore connections for SPHs (Fig. 5). Using superporous poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) hydrogel scaffolds, NIH-3T3 fibroblast cells were encapsulated into superporous PEGDA hydrogels, instead of seeding cells directly onto prefabricated SPH scaffolds.42 These fibroblasts were also encapsulated in NPHs and it was observed that the decrease in number of viable cells was two-folds higher than in SPHs. The main advantages of cell encapsulation are the ability to provide immunoshielding for cells and the possibility of fabricating injectable forms.

FIG. 5.

Schematic illustration of cell culture for nonporous hydrogels (NPHs) and superporous hydrogels (SPHs). Cell seeding onto NPHs will result in cells proliferating on the surface, while cell encapsulation entraps cells within the scaffold. For SPHs, cells will proliferate between the pores when they are seeded onto the scaffolds, or entrapped in the interior during the encapsulation process. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Porosity and Pore Size Measurement Techniques

Various equipment and computer software can be used to measure porosity and pore size of scaffolds. The total porosity is related to the amount of pore space present in the scaffolds. Physical properties such as material or bulk density of the scaffolds can be used to calculate the total porosity. Fluid intrusion methods can also be indirectly used to measure the porosity of scaffolds. Besides using these physical characterization methods, imaging techniques can also be employed for porosity measurements.

Gravimetric method

The total porosity (Π) of scaffolds can be determined by gravimetric method using the bulk and true density of the material as shown in Eq. 1 and 2 below.81,91–93

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where ρscaffold=apparent density of the scaffold and ρmaterial=density of the material.

The volume is calculated by measuring the length, width, and height of the sample. Although this is a simple and fast method, it is a rough estimation of the actual porosity as significant errors can be made while determining the actual volume of the scaffold.93 However, this method is preferred for materials that cannot withstand the high pressures used in other porosity determination methods, for example, layers of nanofiber mats.94

Mercury porosimetry

This method allows the determination of the total pore volume fraction, the average pore diameter, and pore size distribution of 3D materials.93,95,96 Scaffolds are placed in a mercury penetrometer and subsequently infused with mercury under increasing pressures, up to a maximum of 414 MPa (Fig. 6A).11 The mercury is forced into the pores of the scaffolds under high pressures. Since mercury is nonwetting, it only fills the pores when the applied pressure is greater than the tension forces of the surface meniscus. Thus pores that are smaller will have higher tension forces due to greater curvature of surface meniscus and they require higher pressure to fill the pore volume with mercury. This technique has been used to analyze the pore characteristics of various scaffold types, for example, hydroxyapatite scaffolds, poly (α-hydroxy acid) foam scaffold, and electrospun poly (ɛ-caprolactone) nano- or micro-fiber scaffolds.70,81,97–100 Although mercury intrusion is more reliable than others that require manual measurements that might vary based on individuals, it has several drawbacks relating to the high pressures involved. Hence, it should be noted that lower pressures should be used for biomaterials that compress or collapse easily, for example, hydrogels.101 Moreover, materials with thin cross sections may also be destroyed if they are analyzed at high pressures.94 Another disadvantage is the toxicity and cost of mercury.

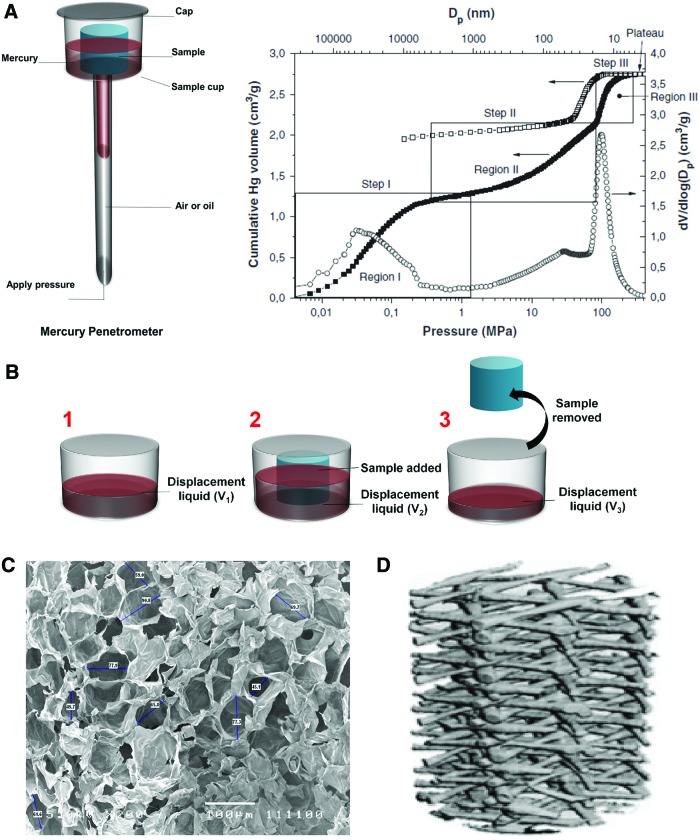

FIG. 6.

Schematic illustration of (A) mercury porosimetry, (B) three-step liquid displacement process, (C) SEM imaging technique, and (D) microcomputed tomography imaging used for porosity or pore size measurement of scaffolds. Images adapted and reproduced by permission of Elsevier and IOP Publishing Ltd. (DOI: 10.1088/1758-5082/3/3/034114).121,122 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

Liquid displacement method

The porosity of scaffolds can also be measured using a displacement liquid that is a not a solvent of the polymers, for example, ethanol, and is capable of penetrating into the pores easily but do not cause size shrinkage or swelling to the material being tested.102 In brief, the scaffold will be placed in a cylinder with a known volume of the displacement liquid and a series of evacuation–repressurization cycles will be done to force the liquid into the pores (Fig. 6B).103 This is also another simple technique that can be carried out easily, but is an indirect way of measuring porosity.

The open porosity can be calculated using the following method (Eq. 3).104–106

|

(3) |

where V1=known volume of liquid that is used to submerge the scaffold (but not a solvent for the scaffold), V2=volume of the liquid and liquid-impregnated scaffold, and V3=remaining liquid volume when the liquid-impregnated scaffold is removed.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis

Various computer software such as SemAfore or ImageJ can be used to analyze scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images to measure pore sizes (Fig. 6C) and porosity.107–111 From the SEM images, an estimation of the cross-sectional area, interconnectivity, and wall thickness can also be obtained.112 However, to obtain accurate measurements, sectioning should be done carefully so as to avoid compression of the scaffold cross section. ImageJ is an image processing program that can be used for various purposes with user-written plugins, for example, 3D live-cell imaging or radiological image processing. For porosity measurements, ImageJ with jPOR macro has been recently established and used to quantify the total optical porosity of blue-stained thin sections.113 This technique allows rapid measurement of porosity from thin section images. It is easy to use and does not require specialist training.

Microcomputed tomography imaging

Microcomputed tomography (Micro-CT) imaging can be used to provide precise information on the 3D morphology of scaffolds (Fig. 6D). During the imaging process, X-rays are used to divide the scaffold into a series of 2D thin sections. The emerging X-rays will be captured by a detector array that calculates the X-ray path and attenuation coefficients.112 The attenuation coefficient will be correlated to the material density to obtain a 2D map that shows the various material phases within the scaffold. Intricate details can be imaged at high resolutions, but longer time and more data storage space is required. Subsequently, 3D modeling programs, for example, Velocity, Anatomics, and Mimics are used to create 3D models from the individual 2D maps obtained earlier. Image thresholding should also be executed before 3D modeling, which would otherwise affect subsequent analysis. This method is noninvasive and does not require any physical sectioning, which enables the scaffold to be reused for other analysis after scanning.11 Moreover, it also eliminates the use of any toxic chemicals.112 Micro-CT is also suitable for scaffolds with intricate interior structures. However, this technique is not suitable for scaffolds that contains metals since X-rays will be heavily attenuated by them, which results in bright and dark grainy scan images that causes loss of important details.112

CAD models

CAD models can be used to design 3D scaffolds of designated structure, pore size, and porosity.114 It is one of the commonly used technologies in the aspect of Computer-Aided Tissue Engineering, where 3D visualization and simulation are enabled for the manufacturing of 3D complex tissue models.115 Rapid prototyping techniques such as 3D printing, stereolithography, and fused deposition modeling utilizes CAD models to reproducibly fabricate very precise structures or biological tissue replicas.61 For CAD models, porosity is calculated from Eq. 4.116

|

(4) |

where Vsolid=volume of solid and Vtotal=total volume of scaffold.

Permeability-based method

Scaffold permeability has been used to determine the pore size and fiber diameter of electrospun fibrinogen scaffolds.117 Using this method, Carr et al. used a flowmeter to pass a fluid through an electrospun scaffold to calculate the scaffold's pore properties.118,119 The amount of fluid that passes through the scaffold area over time is determined. Using this flowmeter designed by Sell et al., the permeability (T) was calculated using the equations shown in Eq. 5 and 6.117–119

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

where p=applied head pressure (Pa), ρ=density of water, g=gravitational force, h=total height of the system (1.5 m), Q=volume of fluid that passed through the scaffold over a period of time (t), η=viscosity of the fluid, hs=thickness of scaffold, and F=cross-sectional area of the scaffold perpendicular to fluid flow.

After obtaining the scaffold permeability values, the pore radius (r) of the scaffold can be calculated according to Eq. 7.

|

(7) |

Capillary flow porometry

This is a nondestructive method that can be used to measure the pore size and distribution of scaffolds. In this technique, a nonreacting gas is used to flow through the scaffold.120 This method can be used on either a dry scaffold or a wet scaffold that is hydrated using a liquid with known surface tension. The change in flow rate is then calculated using the difference in pressure for the dry and wet processes. This technique utilizes low pressure during the process, thus it is suitable for measuring the porous structure of nanofiber membranes. The pore size (D) can be calculated with a software (Porous Media, Inc.) using Eq. 8.

|

(8) |

where Y=surface tension of liquid, θ=contact angle of liquid, and Δp=difference in pressure.

Gradient Porosity

Tissue engineering scaffolds should ideally exhibit similar structural complexity as the native tissue to satisfy the intended biological function. Natural porous materials, including tissues, typically have a gradient porous structure (GPS), in which porosity is not uniform. Rather, it is distributed in such a manner so as to maximize the overall performance of the structure.123 Gradient porosity is observed in bone tissues and this optimizes the material's response to external loading.15 Gradient porosity is also observed in tissues such as the skin, where the pore size increases with distance away from the skin surface. Gradient porosity also enables specific cell migration during tissue regeneration, and is also required for the treatment of articular cartilage defects in osteochondral tissue engineering. In general, macropores are essential to provide space for vascularization and tissue ingrowth, since gas diffusion, nutrient supply, and waste removal is facilitated. However, a denser structure will improve the mechanical properties of scaffolds and enable better cell attachment and intracellular signaling.124,125 Gradient porosity also enables specific cell migration during tissue regeneration, and is also required for the treatment of articular cartilage defects in osteochondral tissue engineering.125,126 Hence, a fine balance between adequate porosity and mechanical stability is required. This will be discussed in more detail in the “Mechanical property” section of this review.

As a potential application in bone tissue engineering, 45S5 Bioglass®-derived glass–ceramic scaffolds with graded pore sizes and different shapes have been produced by foam replication technique, where preformed polyurethane (PU) foams have been used as sacrificial templates.125 These PU foam templates with tailored gradient porosity were compressed using aluminium molds. Hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate (HA/TCP) ceramic scaffolds with gradient porosity were also fabricated using a room temperature camphene-based freeze-casting method as a potential bone graft substitute.127 Calcium phosphate-based ceramics, for example, HA have excellent biocompatibility, bioactivity, and osteoconductivity, thus enabling them to be suitable materials for bone tissue engineering applications. Freeze casting allows the fabrication of graded scaffolds with better mechanical properties than foam replication techniques as the latter generally generates defects during the pyrolysis of the polymer foam template, which results in scaffolds with poorer mechanical properties.128 In the freeze casting process, ceramic slurry that is usually aqueous based, is frozen in a mould at low temperatures, then demoulded, and subsequently sublimated for vehicle removal so as to obtain a green body.129 This freeze casting method showed potential in generating defect-free scaffolds with controlled porosity and pore sizes, and having appropriate compressive properties for tissue engineering applications.127

Cylindrical polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds with gradually increasing pore sizes along the longitudinal direction were also successfully fabricated using a novel centrifugation method developed by Oh et al.130 These scaffolds with pore size gradient were formed by adding fibril-like PCL into a cylindrical mold that was subjected to centrifugation and subsequently heat-treated to enable fibril bonding. The gradual increment of the centrifugal force along the cylindrical axis causes the formation of a pore size gradient. The centrifugal speed can also be adjusted to control the pore size range of the scaffolds. These scaffolds with gradient pore sizes are good tools that can be used for the systemic study of cellular or tissue interaction with scaffolds.

Effect of Porosity and Pore Size on Cell Behavior and Mechanical Property

Cell proliferation and differentiation

Cell behavior is directly affected by the scaffold architecture since the extracellular matrix (ECM) provides cues that influence the specific integrin–ligand interactions between cells and the surrounding (Fig. 7).131 Hence, the 3D scaffold environment can influence cell proliferation or direct cell differentiation. Ma et al. fabricated 3D polyethylene terephthalate (PET) nonwoven fibrous matrix and modified the pore size and porosity by using thermal compression.132 Two types of matrices were studied, namely low porosity (LP) and high porosity (HP). The LP matrices had a porosity of 0.849 and an average pore size of 30 μm, while HP matrices had a porosity of 0.896 and an average pore size of 39 μm. When trophoblast ED27 cells were cultured on these matrices, the initial cell proliferation rate in the LP matrix was observed to be higher than those in the HP matrix. In addition, cells cultured in the LP matrix were able to spread across adjacent fibers more easily, which led to higher cell proliferation rate. However, the smaller pore sizes of LP matrices limited the formation of large cell aggregates and reduced cell differentiation. Conversely, cells cultured in HP matrices had a higher degree of cell differentiation and aggregation. Besides the trophoblast cells, Takahashi and Tabata also demonstrated the effect of 3D nonwoven matrix fabricated using PET fibers on the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of rat mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).133 Thinner PET fibers resulted in lower cell attachment and caused MSCs to have spherical morphologies due to their smaller diameters. Matrices with bigger PET fiber diameters (i.e., greater than 12 μm) and higher porosity (i.e., approximately 96.7%) enhanced cell proliferation rate, which might be due to facilitated transport of nutrients and oxygen in vitro. Thus cellular behavior can be affected by the material properties (e.g., porosity, pore size, interconnectivity, and diameter of fibres) of these 3D nonwoven matrices fabricated from fibers.

FIG. 7.

Effect of (A) pore size and (B) matrix stiffness on MSC behavior. Actin cyoskeleton and nucleus of MSCs were stained with rhodamine–phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue). MSCs were observed to be flattened and grow on the wall of the scaffold with large pores (>100 μm). For collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffold (red) scaffolds with small pores (<50 μm), cells may attach in three-dimensions and differentiate (green nuclei) due to smaller forces present (smaller arrows). When cultured on microenvironments with elasticity of elasticity of 0.1, 11, and 34 kPa, MSCs showed to become neuron-like, myocyte-like, and osteoblasts-like respectively. Images adapted and reproduced by permission of Elsevier.147 Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/teb

The effect of 3D silk fibroin scaffolds on cell proliferation and migration of human foreskin fibroblast showed that pore sizes of 200 to 250 μm and porosity of approximately 86% enabled better cell proliferation.134 However, cell proliferation of these scaffolds with smaller pore sizes of 100 to 150 μm can be improved by having higher porosity of approximately 91%. Hence, by altering the pore size, porosity, or both parameters, the cell viability and proliferation can be enhanced.134–137 Besides affecting the cell proliferation capability, it has been shown that the amount of ECM produced, that is, the amount of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) secretion and the expression of collagen gene markers is also affected by the pore size of scaffolds.138 The study by Lien et al. demonstrated that chondrocytes showed preferential proliferation and ECM production for scaffolds with pore sizes between 250 and 500 μm.138 This pore size range was observed to be capable of maintaining the phenotype of cells, while pores ranging from 50 to 200 μm resulted in cell dedifferentiation.138 In another study, synthetic human elastin (SHE) scaffolds with an average porosity of 34.4% and mean pore size of 11 μm enabled infiltration of dermal fibroblasts, while a lower average porosity of 14.5% and mean pore size of 8 μm only promoted cell proliferation across the scaffold surface.139 The fibroblasts cultured in these SHE scaffolds with higher porosity and larger mean pore sizes also deposited fibronectin and collagen type I over the period of cell culture.139 Thus, the role of porosity and interconnectivity in scaffolds is also to facilitate cell migration within the porous structure such that cell growth is enabled while overcrowding is avoided.

For bone tissue engineering, the optimal pore size for osteoblast activity in tissue engineered scaffolds is still controversial as there have been conflicting reports.140 In general, scaffolds with pore sizes of about 20 to 1500 μm have been used.140–143 Akay et al. studied the behavior of osteoblasts in PolyHIPE polymer (PHP), a type of highly porous polymeric foam.144 The osteoblasts were shown to populate more in smaller pores (40 μm) when they were grown in scaffolds with different pore sizes, but larger pore sizes (100 μm) facilitated cell migration. However, the different pore sizes did not have any effect on extent of mineralization or cell penetration depth.144 Collagen–GAG (CG) scaffolds were also studied to determine its optimal pore size for bone tissue engineering purposes and the effect of pore size on a preosteoblastic cell line, MC3T3-E1.140 From the results, optimal cell proliferation and infiltration was found in CG scaffolds with mean pore sizes greater than 300 μm. In addition, the ability of larger pores to facilitate cell infiltration was shown to override the beneficial effect of greater initial cell attachment surface areas provided by smaller pores. Hence, this study supported previous reports that suggested the importance of having pore sizes greater than 300 μm for osteogenesis to occur.145 However, it should be noted that cell differentiation is also dependent on the cell type, scaffold material, and fabrication conditions.146

Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is the growth of new blood vessels from existing vasculature, which is essential to supply oxygen and nutrients to developing tissues, and to facilitate wound healing.148 Scaffolds were seeded with stem cells and/or endothelial cells or incorporated with angiogenic factors to promote angiogenesis.148–151 The minimum porosity necessary for the regeneration of a blood vessel is approximately 30 to 40 μm to enable the exchange of metabolic components and to facilitate endothelial cell entrance.152,153 Artel et al. showed that larger pore sizes of approximately 160 to 270 μm facilitated angiogenesis throughout scaffold by using multilayered agent-based model simulation.154 This model was used to investigate the relationship between angiogenesis and scaffold properties. The materials were assumed to be slowly degrading or nondegradable, such that the pore sizes remained constant. It has also been demonstrated that vascularization of constructs necessitates pores greater than 300 μm.145,155 The range of pore size suitable for the different types of cellular activities is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pore Sizes and Porosity of Various Scaffold Types Required for Different Cellular Activities

| Function | Cell type used/in vivo tests | Scaffold material | Pore size (μm) | Porosity (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiogenesis | Multilayered agent-based model simulation/in vivo rat implantation | Porous PEG | 160–270 | — | 154 |

| Adipogenesis | Murine embryonic stem cells | PCL | 6–70 | 88 | 156 |

| Rat BMCs | Silk gland fibroin from nonmulberry | 90–110 | 97 | 157 | |

| Mice ASCs | Porcine type 1 collagen | 70–110 | — | 158 | |

| Cell infiltration | Dermal fibroblasts | Synthetic human elastin | 11 | 34.4 | 139 |

| Primary rat osteoblasts | PHP | 100 | — | 144 | |

| Chondrogenesis | Human ASCs | PCL | 370–400 | 95 | 146 |

| Porcine chondrocytes | Chitosan | 70–120 | 80 | 159 | |

| Rabbit MSCs | PLGA-GCH | 200 | 74 | 160 | |

| Rabbit MSCs | PLGA | 200–500 | — | 161 | |

| Porcine chondrocytes | PCL | 750 | 30 | 162 | |

| Porcine BMSCs | PCL | 860 | 59 | 162 | |

| Hepatogenesis | Human ASCs | PLGA | 120–200 | — | 163 |

| Rat bone marrow stem cells | c-PLGA | 150–350 | 94 | 164 | |

| Osteogenesis | In vivo rat implantation | Hydroxyapatite-BMPs | 300–400 | — | 145 |

| hMSCs | Coralline hydroxyapatite | 200 | 75 | 136 | |

| In vivo mice implantation | β-tricalcium phosphate | 2–100 | 75 | 165 | |

| In vivo mice implantation | Natural coral | 150–200 | 35 | 166 | |

| RBMSCs | Sintered titanium | 250 | 86 | 167 | |

| Fetal bovine osteoblasts | PCL | 350 | 65 | 168 | |

| Proliferation | hMSCs | Coralline hydroxyapatite | 500 | 88 | 136 |

| Human trophoblast ED27 | PET | 30 | 84.9 | 132 | |

| Rat MSCs | PET | >12 | 96.7 | 133 | |

| Human foreskin fibroblasts | Silk fibroin | 200–250 | 86 | 134 | |

| Human foreskin fibroblasts | Silk fibroin | 100–150 | 91 | 134 | |

| Rat chondrocytes | Type A gelatin | 250–500 | — | 138 | |

| MC3T3-E1 cells | CG | 325 | 99 | 140 | |

| Primary rat osteoblasts | PHP | 40 | — | 144 | |

| Skin regeneration | Guinea pig dermal and epidermal cells | CG | 20–125 | — | 169 |

| Smooth muscle cell differentitation | Dog BMSCs | PLGA | 50–200 | — | 170 |

BMCs, bone marrow cells; ASCs, adipose-derived stem cells; hMSCs, human mesenchymal stem cells; BMSCs, bone marrow stem cells; PEG, poly(ethylene glycol); PCL, polycaprolactone; PET, polyethylene terephthalate; CG, Collagen–glycosaminoglycan; PHP, PolyHIPE polymer; cPLGA-GCH, collagen-coated poly-lactide-co-glycolide–gelatin/chondroitin/hyaluronate; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; RBMSCs, rat bone marrow stromal cells.

Mechanical property

Besides affecting the cell behavior and differentiation potential, the porosity and pore sizes of the scaffolds also have an effect on the mechanical properties. Although higher porosity and pore sizes may facilitate nutrient and oxygen delivery or enable more cell ingrowth, the mechanical properties of the scaffolds will be compromised due to the large amount of void volume.11 Hence, there is a limit to the amount of porosity or pore sizes that could be incorporated into a scaffold without compromising its mechanical properties to a great extent. In general, scaffolds should have sufficient mechanical strength to maintain integrity until new tissue regeneration. There should also be sufficient space for cells to proliferate and to enable the transport of nutrients and removal of wastes.20,21 Moreover, it is important that the material property of the scaffolds matches the native tissue in vivo, for example, scaffolds fabricated for bone tissue engineering should have comparable strength to the native bone tissue to withstand physiological loadings and to prevent stress shielding from occurring.20 Although the mechanical property of scaffolds is compromised with higher porosity or pore sizes, the use of materials with high inherent mechanical strength might be a solution to this issue.134

Nature's Own Scaffold: The ECM

In native tissues, the ECM is a heterogeneous component of functional proteins, proteoglycans, and signaling molecules arranged in a specific 3D manner enriched with cellular components and a variety of growth factors, cytokines, ions, and water to provide structural support to cells.171–173 The ECM is an important component in growth and wound healing, and from recent studies it has been shown to be a vital factor in cell signaling.174–177 Newly formed ECM is secreted by exocytosis after the components are produced by the resident cells. It has now been shown that the ECM is capable of directing cell behavior such as proliferation, differentiation, and migration via biomechanical interactions and mechanical cues.69 Hence, the ECM is nature's own multifunctional scaffold that not only imparts structural integrity to the tissues, but also modulates a wide range of cellular behaviors.178 Reviews on the role of ECM properties and mechanism of cell–ECM interactions on cell adhesion, migration, and matrix assembly have been covered by several groups.179–181

The ultimate aim of tissue scaffolding strategies is to mimic the actual 3D microenvironment that is the ECM. As with all scaffolds, it is important to consider the pore structure of the native ECM of the tissue that is to be replaced or reconstructed. Different tissues have their own unique ECM composition and structure.182 In general, the ECM is a porous mesh network of proteins and GAGs that can be altered by cross-linking and enhancing the barrier function of the matrix.183 Cross-linking of the ECM is associated with local cross-linking of collagen and elastin by lysyl oxidase.184–186 The increase in cross-linking also inevitably results in a reduction of the matrix porosity. Collagenases can increase the matrix porosity by disrupting the ECM network through uncoiling the triple-helical structure of collagen and exposing sites for proteolysis to occur. ECM degradation, which is associated with matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), also leads to an increase in porosity.187,188 Normally, remodeling of the ECM is dependent on the balance between MMPs and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases. Remodeling of the ECM is essential to promote normal physiological processes such as development, wound repair, and morphogenesis.174,187 In fact, changes in ECM structure and composition is also an indication of tissue health and disease progression.189,190 Some groups have attempted to incorporate biological cues such as MMPs and vascular endothelial growth factor to facilitate ECM degradation, cell proliferation, angiogenesis, or regeneration.191–193 Amino acid sequence-Arg-Gly-Asp- (RGD) peptide can also be attached to scaffolds to enhance cell attachment or mineralization.194–197 Besides these biological factors, another approach taken to mimic the ECM properties is to directly conjugate ECM molecules to the scaffolds during fabrication or to use decellularized tissues as ECM scaffolds.198–201 The ECM can be obtained from decellularized tissues and organs, for example, nerve, liver, and respiratory tract.202–205 The advantage of incorporating ECM into the scaffolds is to improve tissue specificity and to facilitate maintenance of cell functions and phenotype.205 On the whole, all these different approaches intend to create a 3D microenvironment that behaves like the actual tissue ECM to be successfully used in various tissue engineering applications.

Tunable Scaffolds

Most conventional methods used to fabricate porous scaffolds typically do not allow the porosity or pore size to be tuned once the scaffold is created. In this situation, the use of scaffolds that do not degrade fast enough results in restricted cell migration and proliferation, and nutrient and oxygen deficiencies within the developing tissue. On the other hand, a scaffold that degrades too fast can compromise mechanical and structural integrity of the implant before the tissue is sufficiently well developed. In both cases, tissue regeneration is inhibited due to a mismatch between the rates of tissue growth and scaffold degeneration. The engineering of a “smart” tunable scaffold system that can accommodate widely different regeneration rates of different tissues due to individual differences in age, dietary intake, healing rates, and lifestyle-related factors is thus highly crucial yet challenging. Such scaffolds with postfabrication tunability are essential so as to provide a suitable microenvironment for these dynamic changes, for example, migration and differentiation.206,207

Amongst limited literature, the use of photostimulus seems to be popular for on-demand triggered functionalities and tunability in scaffolds. Works reported by Kloxin et al. have demonstrated the synthesis of photodegradable macromers and their subsequent polymerization to form hydrogels whose physical, chemical, and biological properties can be tuned in situ and in the presence of cells by ultraviolet, visible, or two-photon irradiation.208,209 These macromers are cytocompatible and allows remote manipulation of gel properties in situ. Postgelation control of the gel properties was demonstrated to introduce temporal changes, creation of arbitrarily shaped features, and on-demand pendant functionality release, which allows cell migration and chondrogenic differentiation of encapsulated stem cells in vitro. These photodegradable gels can be used for culturing cells in three dimensions and allowing real-time, externally triggered manipulation of the cell microenvironment to examine its dynamic effect on cell function. However, one disadvantage of this system is the longer degradation time with 365 nm light that may affect cell viability.208,210

Various studies on reversible hydrogel fabrication by dimerization of nitrocinnamate have also been tested, but the disadvantage of this system is the requirement of irradiation light in the cytotoxic range (254 nm).211,212 In another attempt to improve this system, Griffin and Kasko incorporated the photodegradable o-NB linker to various PEG-based macromers such that they can photolyze over a broad range of rates.212 These hydrogels have been used to encapsulate human MSCs (hMSCs) and the biased release of one stem cell population (green-fluoroescent protein expressing hMSCs) over another (red-fluorescent protein expressing hMSCs) by exploiting the differences in reactivity of two different o-NB linkers was demonstrated.

Conclusion

Porous 3D scaffolds are commonly used in tissue engineering applications and can be fabricated from various conventional and rapid prototyping techniques, depending on the type of materials used or type of pore structures needed. These scaffolds serve to provide suitable microenvironments to support cell growth and function. The structural properties of the scaffolds, for example, porosity and pore size have direct implications on their functionality both in vitro and in vivo. Generally, interconnected porous scaffold networks that enable the transport of nutrients, removal of wastes, and facilitate proliferation and migration of cells are essential. The porosity and pore size influences cell behavior and determine the final mechanical property of the scaffold. Various techniques, equipments, or computer software have also been developed and used for pore size and porosity measurements.

The purpose of fabricating scaffolds is to produce tissue-like materials such that they can eventually perform like the native tissues. Currently, the idea of scaffold fabrication is based on creating materials with optimum pore size, structure, and porosity for various applications. Generally, scaffolds are first created and cells are subsequently cultured on these scaffolds. As such, there are some existing limitations to this current approach. These prefabricated scaffolds have certain material property that may or may not be suitable to support normal cell growth or differentiation. Incompatibility of the scaffold with the cellular application will eventually lead to the failure of the entire tissue-engineered scaffolding system. Hence, an in-depth analysis is necessary to evaluate the exact porosity and pore size that is optimal for each scaffold system such that they complement the intended type of tissue engineering application. Also, to mimic the actual situation where the ECM undergoes continuous remodeling or healing processes, scaffolds with postfabrication tunability are essential so as to provide a suitable microenvironment for these dynamic changes.

This review provides a general overview that facilitates the understanding of porous scaffold fabrication and pore size and porosity measurement techniques. In addition, the effect of porosity and pore size on cellular behavior and mechanical property of scaffolds was also covered to illustrate the whole concept of the importance of the role of porosity and pore size in tissue engineering applications.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Luu Y.K. Kim K. Hsiao B.S. Chu B. Hadjiargyrou M. Development of a nanostructured DNA delivery scaffold via electrospinning of PLGA and PLA-PEG block copolymers. J Control Release. 2003;89:341. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cabral J. Moratti S.C. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Future Med Chem. 2011;3:1877. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiselt P. Yeh J. Latvala R.K. Shea L.D. Mooney D.J. Porous carriers for biomedical applications based on alginate hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1921. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaigler D. Wang Z. Horger K. Mooney D.J. Krebsbach P.H. VEGF scaffolds enhance angiogenesis and bone regeneration in irradiated osseous defects. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:735. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu Y.C. Larson J.C. Isom A. Brey E.M. Generation of porous poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels by salt leaching. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:905. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salerno A. Di Maio E. Iannace S. Netti P. Tailoring the pore structure of PCL scaffolds for tissue engineering prepared via gas foaming of multi-phase blends. J Porous Mater. 2012;19:181. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollister S. Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2005;4:518. doi: 10.1038/nmat1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Tsang V. Bhatia S.N. Three-dimensional tissue fabrication. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1635. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chevalier E. Chulia D. Pouget C. Viana M. Fabrication of porous substrates: a review of processes using pore forming agents in the biomaterial field. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:1135. doi: 10.1002/jps.21059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Causa F. Netti P.A. Ambrosio L. A multi-functional scaffold for tissue regeneration: the need to engineer a tissue analogue. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5093. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karageorgiou V. Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung H.J. Meredith C. Johnson C. Galis Z.S. The effect of scaffold degradation rate on three-dimensional cell growth and angiogenesis. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5735. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buckley C. O'Kelly K. Regular scaffold fabrication techniques for investigations in tissue engineering. In: Prendergast P.J., editor; McHugh P.E., editor. Topics in bio-mechanical engineering. Dublin, Ireland: Trinity Centre for Bioengineering & National Centre for Biomedical Engineering Science; 2004. pp. 147–166. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma P.X. Scaffolds for tissue fabrication. Mater Today. 2004;7:30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pompe W. Worch H. Epple M. Friess W. Gelinsky M. Greil P. Hempel U. Scharnweber D. Schulte K. Functionally graded materials for biomedical applications. Mater Sci Eng A. 2003;362:40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeong W.Y. Chua C.K. Leong K.F. Chandrasekaran M. Rapid prototyping in tissue engineering: challenges and potential. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:643. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goulet R.W. Goldstein S.A. Ciarelli M.J. Kuhn J.L. Brown M.B. Feldkamp L.A. The relationship between the structural and orthogonal compressive properties of trabecular bone. J Biomech. 1994;27:375. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu T.M.G. Orton D.G. Hollister S.J. Feinberg S.E. Halloran J.W. Mechanical and in vivo performance of hydroxyapatite implants with controlled architectures. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1283. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherwood J.K. Riley S.L. Palazzolo R. Brown S.C. Monkhouse D.C. Coates M. Griffith L.G. Landeen L.K. Ratcliffe A. A three-dimensional osteochondral composite scaffold for articular cartilage repair. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4739. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leong K.F. Chua C.K. Sudarmadji N. Yeong W.Y. Engineering functionally graded tissue engineering scaffolds. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2008;1:140. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leong K.F. Cheah C.M. Chua C.K. Solid freeform fabrication of three-dimensional scaffolds for engineering replacement tissues and organs. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2363. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang S. Leong K.F. Du Z. Chua C.K. The design of scaffolds for use in tissue engineering. Part II. Rapid prototyping techniques. Tissue Eng. 2002;8:1. doi: 10.1089/107632702753503009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichol J.W. Khademhosseini A. Modular tissue engineering: engineering biological tissues from the bottom up. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1312. doi: 10.1039/b814285h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C. Vepari C. Jin H.J. Kim H.J. Kaplan D.L. Electrospun silk-BMP-2 scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3115. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zong X. Bien H. Chung C.Y. Yin L. Fang D. Hsiao B.S. Chu B. Entcheva E. Electrospun fine-textured scaffolds for heart tissue constructs. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5330. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K. Yu M. Zong X. Chiu J. Fang D. Seo Y.S. Hsiao B.S. Chu B. Hadjiargyrou M. Control of degradation rate and hydrophilicity in electrospun non-woven poly(D,L-lactide) nanofiber scaffolds for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4977. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00407-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung H.J. Park T.G. Surface engineered and drug releasing pre-fabricated scaffolds for tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:249. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei B. Shin K.H. Noh D.Y. Jo I.H. Koh Y.H. Choi W.Y. Kim H.E. Nanofibrous gelatin–silica hybrid scaffolds mimicking the native extracellular matrix (ECM) using thermally induced phase separation. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:14133. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montero R.B. Vial X. Nguyen D.T. Farhand S. Reardon M. Pham S.M. Tsechpenakis G. Andreopoulos F.M. bFGF-containing electrospun gelatin scaffolds with controlled nano-architectural features for directed angiogenesis. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:1778. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seyednejad H. Gawlitta D. Kuiper R.V. de Bruin A. van Nostrum C.F. Vermonden T. Dhert W.J.A. Hennink W.E. In vivo biocompatibility and biodegradation of 3D-printed porous scaffolds based on a hydroxyl-functionalized poly(ɛ-caprolactone) Biomaterials. 2012;33:4309. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seck T.M. Melchels F.P.W. Feijen J. Grijpma D.W. Designed biodegradable hydrogel structures prepared by stereolithography using poly(ethylene glycol)/poly(D,L-lactide)-based resins. J Control Release. 2010;148:34. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeong W.Y. Sudarmadji N. Yu H.Y. Chua C.K. Leong K.F. Venkatraman S.S. Boey Y.C.F. Tan L.P. Porous polycaprolactone scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering fabricated by selective laser sintering. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2028. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melchels F. Wiggenhauser P.S. Warne D. Barry M. Ong F.R. Chong W.S. Hutmacher D.W. Schantz J.T. CAD/CAM-assisted breast reconstruction. Biofabrication. 2011;3:034114. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/3/3/034114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duan B. Wang M. Zhou W.Y. Cheung W.L. Li Z.Y. Lu W.W. Three-dimensional nanocomposite scaffolds fabricated via selective laser sintering for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4495. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elomaa L. Teixeira S. Hakala R. Korhonen H. Grijpma D.W. Seppälä J.V. Preparation of poly(ɛ-caprolactone)-based tissue engineering scaffolds by stereolithography. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:3850. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma P.X. Langer R. Fabrication of biodegradable polymer foams for cell transplantation and tissue engineering. Methods Mol Med. 1999;18:47. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-516-6:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu L. Peter S.J. Lyman M.D. Lai H.L. Leite S.M. Tamada J.A. Vacanti J.P. Langer R. Mikos A.G. In vitro degradation of porous poly(L-lactic acid) foams. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1595. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee S.B. Kim Y.H. Chong M.S. Hong S.H. Lee Y.M. Study of gelatin-containing artificial skin V: fabrication of gelatin scaffolds using a salt-leaching method. Biomaterials. 2005;26:1961. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G. Ushida T. Tateishi T. Scaffold design for tissue engineering. Macromol Biosci. 2002;2:67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nam Y.S. Yoon J.J. Park T.G. A novel fabrication method of macroporous biodegradable polymer scaffolds using gas foaming salt as a porogen additive. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;53:1. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(2000)53:1<1::aid-jbm1>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mooney D.J. Baldwin D.F. Suh N.P. Vacanti J.P. Langer R. Novel approach to fabricate porous sponges of poly(D,L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) without the use of organic solvents. Biomaterials. 1996;17:1417. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)87284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keskar V. Marion N.W. Mao J.J. Gemeinhart R.A. In vitro evaluation of macroporous hydrogels to facilitate stem cell infiltration, growth, and mineralization. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1695. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wachiralarpphaithoon C. Iwasaki Y. Akiyoshi K. Enzyme-degradable phosphorylcholine porous hydrogels cross-linked with polyphosphoesters for cell matrices. Biomaterials. 2007;28:984. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mikos A. Temenoff J. Formation of highly porous biodegradable scaffolds for tissue engineering. Electron J Biotechnol. 2000;3:23. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nam Y.S. Park T.G. Porous biodegradable polymeric scaffolds prepared by thermally induced phase separation. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;47:8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199910)47:1<8::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schugens C. Maquet V. Grandfils C. Biodegradable and macroporous polylactide implants for cell transplantation: 1. Preparation of macroporous polylactide supports by solid-liquid phase separation. Polymer. 1996;37:1027. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199604)30:4<449::AID-JBM3>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schugens C. Maquet V. Grandfils C. Jerome R. Teyssie P. Polylactide macroporous biodegradable implants for cell transplantation. II. Preparation of polylactide foams by liquid-liquid phase separation. J Biomed Mater Res. 1996;30:449. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199604)30:4<449::AID-JBM3>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sachlos E. Czernuszka J.T. Making tissue engineering scaffolds work. Review: the application of solid freeform fabrication technology to the production of tissue engineering scaffolds. Eur Cell Mater. 2003;5:29. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v005a03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whang K. Thomas C. Healy K. Nuber G. A novel method to fabricate bioabsorbable scaffolds. Polymer. 1995;36:837. [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Brien F.J. Harley B.A. Yannas I.V. Gibson L. Influence of freezing rate on pore structure in freeze-dried collagen-GAG scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1077. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu C. Luo Y. Cuniberti G. Xiao Y. Gelinsky M. Three-dimensional printing of hierarchical and tough mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds with a controllable pore architecture, excellent mechanical strength and mineralization ability. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:2644. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seitz H. Rieder W. Irsen S. Leukers B. Tille C. Three-dimensional printing of porous ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2005;74:782. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Curodeau A. Sachs E. Caldarise S. Design and fabrication of cast orthopedic implants with freeform surface textures from 3-D printed ceramic shell. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;53:525. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200009)53:5<525::aid-jbm12>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim S.S. Utsunomiya H. Koski J.A. Wu B.M. Cima M.J. Sohn J. Mukai K. Griffith L.G. Vacanti J.P. Survival and function of hepatocytes on a novel three-dimensional synthetic biodegradable polymer scaffold with an intrinsic network of channels. Ann Surg. 1998;228:8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199807000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams J.M. Adewunmi A. Schek R.M. Flanagan C.L. Krebsbach P.H. Feinberg S.E. Hollister S.J. Das S. Bone tissue engineering using polycaprolactone scaffolds fabricated via selective laser sintering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4817. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hutmacher D. Sittinger M. Risbud M. Scaffold-based tissue engineering: rationale for computer-aided design and solid free-form fabrication systems. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:354. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paul B. Baskaran S. Issues in fabricating manufacturing tooling using powder-based additive freeform fabrication. J Mater Proc Technol. 1996;61:168. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tan K.H. Chua C.K. Leong K.F. Cheah C.M. Cheang P. Abu Bakar M.S. Cha S.W. Scaffold development using selective laser sintering of polyetheretherketone-hydroxyapatite biocomposite blends. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3115. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rimell J.T. Marquis P.M. Selective laser sintering of ultra high molecular weight polyethylene for clinical applications. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;53:414. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(2000)53:4<414::aid-jbm16>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dhariwala B. Hunt E. Boland T. Rapid prototyping of tissue-engineering constructs, using photopolymerizable hydrogels and stereolithography. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1316. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Draget K. Skjak-Braek G. Smidsrod O. Alginate based new materials. Int J Biol Macromol. 1997;21:47. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(97)00040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang W.L. Cheah C.M. Fuh J.Y.H. Lu L. Influence of process parameters on stereolithography part shrinkage. Materials and Design. 1996;17:205. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harris R. Newlyn H. Hague R. Dickens P. Part shrinkage anomilies from stereolithography injection mould tooling. Int J Mach Tools Manufacture. 2003;43:879. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zein I. Hutmacher D.W. Tan K.C. Teoh S.H. Fused deposition modeling of novel scaffold architectures for tissue engineering applications. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1169. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xia Z. Ye H. Choong C. Ferguson D.J.P. Platt N. Cui Z. Triffitt J.T. Macrophagic response to human mesenchymal stem cell and poly(ɛ-caprolactone) implantation in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient mice. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;71:538. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choong C. Triffitt J. Cui Z. Polycaprolactone scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: effects of a calcium phosphate coating layer on osteogenic cells. Food Bioproducts Proc. 2004;82:117. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cipitria A. Skelton A. Dargaville T. Dalton P. Hutmacher D. Design, fabrication and characterization of PCL electrospun scaffolds—a review. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:9419. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lim S. Mao H. Electrospun scaffolds for stem cell engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:1084. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mi F.L. Shyu S.S. Chen C.T. Schoung J.Y. Porous chitosan microsphere for controlling the antigen release of Newcastle disease vaccine: preparation of antigen-adsorbed microsphere and in vitro release. Biomaterials. 1999;20:1603. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pham Q. Sharma U. Mikos A. Electrospun poly (ɛ-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/microfiber scaffolds: characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2796. doi: 10.1021/bm060680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lannutti J. Reneker D. Ma T. Tomasko D. Farson D. Electrospinning for tissue engineering scaffolds. Mater Sci Eng C. 2007;27:504. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liang D. Hsiao B. Chu B. Functional electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:1392. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pramanik S. Pingguan-Murphy B. Osman N. Progress of key strategies in development of electrospun scaffolds: bone tissue. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2012;13:043002. doi: 10.1088/1468-6996/13/4/043002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lin S. Bhattacharyya D. Fakirov S. Matthews B. Cornish J. Comparison of nanoporous scaffolds manufactured by electrospinning and nanofibrillar composite concept. 18th International Conference on Composite Materials; Edinburgh, Scotland. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fang J. Zhang L. Sutton D. Wang X. Lin T. Needleless melt-electrospinning of polypropylene nanofibres. J Nanomater. 2012;2012:16. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dalton P.D. Grafahrend D. Klinkhammer K. Klee D. Möller M. Electrospinning of polymer melts: phenomenological observations. Polymer. 2007;48:6823. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lyons J. Li C. Ko F. Melt-electrospinning part I: processing parameters and geometric properties. Polymer. 2004;45:7597. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ogata N. Yamaguchi S. Shimada N. Lu G. Iwata T. Nakane K. Ogihara T. Poly (lactide) nanofibers produced by a melt-electrospinning system with a laser melting device. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;104:1640. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Deng R. Liu Y. Ding Y. Xie P. Luo L. Yang W. Melt electrospinning of low-density polyethylene having a low-melt flow index. J Appl Polym Sci. 2009;114:166. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Orive G. Hernández R.M. Gascón A.R. Calafiore R. Chang T.M.S. De Vos P. Hortelano G. Hunkeler D. Lacík I. Shapiro A.M.J. Pedraz J.L. Cell encapsulation: promise and progress. Nat Med. 2003;9:104. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hu Y. Grainger D.W. Winn S.R. Hollinger J.O. Fabrication of poly (α-hydroxy acid) foam scaffolds using multiple solvent systems. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:563. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hunt N. Grover L. Cell encapsulation using biopolymer gels for regenerative medicine. Biotechnol Lett. 2010;32:733. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nicodemus G.D. Bryant S.J. Cell encapsulation in biodegradable hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14:149. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Diaspro A. Silvano D. Krol S. Cavalleri O. Gliozzi A. Single living cell encapsulation in nano-organized polyelectrolyte shells. Langmuir. 2002;18:5047. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Karoubi G. Ormiston M.L. Stewart D.J. Courtman D.W. Single-cell hydrogel encapsulation for enhanced survival of human marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5445. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Uludag H. De Vos P. Tresco P.A. Technology of mammalian cell encapsulation. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;42:29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Vos P. Marchetti P. Encapsulation of pancreatic islets for transplantation in diabetes: the untouchable islets. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:363. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Loh Q.L. Wong Y.Y. Choong C. Combinatorial effect of different alginate compositions, polycations, and gelling ions on microcapsule properties. Colloid Polymer Sci. 2012;290:619. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Acarregui A. Murua A. Pedraz J.L. Orive G. Hernández R.M. A perspective on bioactive cell microencapsulation. BioDrugs. 2012;26:283. doi: 10.1007/BF03261887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Städler B. Price A.D. Zelikin A.N. A critical look at multilayered polymer capsules in biomedicine: drug carriers, artificial organelles, and cell mimics. Adv Funct Mater. 2011;21:14. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maspero F.A. Ruffieux K. Müller B. Wintermantel E. Resorbable defect analog PLGA scaffolds using CO2 as solvent: structural characterization. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:89. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim H.W. Knowles J.C. Kim H.E. Hydroxyapatite/poly(ɛ-caprolactone) composite coatings on hydroxyapatite porous bone scaffold for drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1279. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guarino V. Causa F. Taddei P. di Foggia M. Ciapetti G. Martini D. Fagnano C. Baldini N. Ambrosio L. Polylactic acid fibre-reinforced polycaprolactone scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3662. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L. Semnani D. Morshed M. A novel method for porosity measurement of various surface layers of nanofibers mat using image analysis for tissue engineering applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;106:2536. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mayer R. Stowe R. Mercury porosimetry—breakthrough pressure for penetration between packed spheres. J Colloid Sci. 1965;20:893. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shum A.W. Li J. Mak A.F. Fabrication and structural characterization of porous biodegradable poly(dl-lactic-co-glycolic acid) scaffolds with controlled range of pore sizes. Polym Degrad Stability. 2005;87:487. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ma J. Wang C. Peng K. Electrophoretic deposition of porous hydroxyapatite scaffold. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3505. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li W. Laurencin C. Caterson E. Tuan R. Ko F. Electrospun nanofibrous structure: a novel scaffold for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;60:613. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pham Q. Sharma U. Mikos A. Electrospun poly (ɛ-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/microfiber scaffolds: characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:2796. doi: 10.1021/bm060680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Min B. Lee G. Kim S. Nam Y. Lee T. Park W. Electrospinning of silk fibroin nanofibers and its effect on the adhesion and spreading of normal human keratinocytes and fibroblasts in vitro. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1289. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.y Leon L. Carlos A. New perspectives in mercury porosimetry. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 1998;76:341. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shi G. Cai Q. Wang C. Lu N. Wang S. Bei J. Fabrication and biocompatibility of cell scaffolds of poly(L-lactic acid) and poly(L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) Polym Adv Technol. 2002;13:227. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang Y. Zhang M. Synthesis and characterization of macroporous chitosan/calcium phosphate composite scaffolds for tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55:304. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010605)55:3<304::aid-jbm1018>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhao F. Yin Y. Lu W.W. Leong J.C. Zhang W. Zhang J. Zhang M. Yao K. Preparation and histological evaluation of biomimetic three-dimensional hydroxyapatite/chitosan-gelatin network composite scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2002;23:3227. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nazarov R. Jin H.J. Kaplan D.L. Porous 3-D scaffolds from regenerated silk fibroin. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:718. doi: 10.1021/bm034327e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang R. Ma P.X. Poly(alpha-hydroxyl acids)/hydroxyapatite porous composites for bone-tissue engineering. I. Preparation and morphology. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;44:446. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19990315)44:4<446::aid-jbm11>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Oh S.H. Kang S.G. Kim E.S. Cho S.H. Lee J.H. Fabrication and characterization of hydrophilic poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend cell scaffolds by melt-molding particulate-leaching method. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4011. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Damien E. Hing K. Saeed S. Revell P.A. A preliminary study on the enhancement of the osteointegration of a novel synthetic hydroxyapatite scaffold in vivo. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:241. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.El-Ghannam A.R. Advanced bioceramic composite for bone tissue engineering: design principles and structure-bioactivity relationship. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;69:490. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kim H.D. Valentini R.F. Retention and activity of BMP-2 in hyaluronic acid-based scaffolds in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:573. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Park S.N. Park J.C. Kim H.O. Song M.J. Suh H. Characterization of porous collagen/hyaluronic acid scaffold modified by 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide cross-linking. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1205. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ho S.T. Hutmacher D.W. A comparison of micro CT with other techniques used in the characterization of scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1362. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Grove C. Jerram D.A. jPOR: an ImageJ macro to quantify total optical porosity from blue-stained thin sections. Comput Geosci. 2011;37:1850. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sun W. Starly B. Darling A. Gomez C. Computer-aided tissue engineering: application to biomimetic modelling and design of tissue scaffolds. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2004;39:49. doi: 10.1042/BA20030109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sun W. Starly B. Nam J. Darling A. Bio-CAD modeling and its applications in computer-aided tissue engineering. Comput Aided Des. 2005;37:1097. [Google Scholar]