Abstract

Group Motivational Interviewing (MI) interventions that target youth at-risk for alcohol and other drug (AOD) use may prevent future negative consequences. Youth in a teen court setting (n=193; 67% male, 45% Hispanic; mean age 16.6 (SD = 1.05) were randomized to receive either a group MI intervention, Free Talk, or usual care (UC). We examined client acceptance, intervention feasibility and conducted a preliminary outcome evaluation. Free Talk teens reported higher quality and satisfaction ratings, and MI integrity scores were higher for Free Talk groups. AOD use and delinquency decreased for both groups at three months, and 12-month recidivism rates were lower but not significantly different for the Free Talk group compared to UC. Results contribute to emerging literature on MI in a group setting. A longer term follow-up is warranted.

1. Introduction

An unacceptably high proportion of youth still report using alcohol (33% of 8th graders, 70% of 12th graders) and marijuana (16% of 8th graders, 45% of 12th graders) in their lifetime (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012). It is well known that regular use of alcohol and other drugs (AOD) during adolescence is associated with serious negative consequences. For example, many youth report having unprotected sex while under the influence of AOD (Levy, Sherritt, Gabrielli, Shrier, & Knight, 2009), and AOD use is associated with poorer physical and mental health and delinquent behavior (D'Amico, Edelen, Miles, & Morral, 2008; Ford, 2005). In addition, AOD use during this developmental period may significantly affect normal brain maturation and cognitive development (Manzar, Cervellione, Cottone, Ardekani, & Kumra, 2009; Tapert & Schweinsburg, 2005), and increase the likelihood of psychosocial, health, emotional, and financial problems in early and late adulthood (Aseltine & Gore, 2005; Brown, et al., 2009; Jackson & Sartor, in press; Oesterle, Hill, Hawkins, Guo, & Catalano, 2004; Patton, et al., 2007).

Interventions that target at-risk youth who report AOD use may reduce the risk of these consequences by potentially decreasing use before more intensive treatment is required. One approach that has demonstrated particular promise with youth of different ages and races/ethnicities is motivational interviewing (MI) (Miller & Rollnick, 2012; Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2008). The transportability of MI has made it ideal in reaching youth across a variety of settings, including juvenile justice, medical clinics, homeless shelters, and schools (Baer, Garrett, Beadnell, Wells, & Peterson, 2007; D'Amico, Miles, Stern, & Meredith, 2008; Feldstein & Ginsburg, 2006; Martin & Copeland, 2008; McCambridge, Slym, & Strang, 2008; Peterson, Baer, Wells, Ginzler, & Garrett, 2006; Spirito, et al., 2004; Stein, et al., 2011; Walker, Roffman, Stephens, Wakana, & Berghuis, 2006). Not only is this collaborative and strength-based intervention transportable, it has also been shown to be effective across a number of substance use and health risk behaviors (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005; Jofre-Bonet & Sindelar, 2001; Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010). Moreover, it appears to be particularly effective at facilitating therapeutic alliance with individuals ambivalent to behavioral change, such as non-treatment-seeking youth who report at-risk AOD use (D'Amico, Miles, et al., 2008; McCambridge, et al., 2008; Peterson, et al., 2006). Additionally, studies using qualitative methods have suggested that the MI approach resonates with adolescents, with high percentages of youth reporting that they enjoyed the MI intervention and would recommend it to a friend (D'Amico, Osilla, & Hunter, 2010; D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2012; D'Amico, Tucker, et al., 2012; Martin & Copeland, 2008; Stern, Meredith, Gholson, Gore, & D’Amico, 2007). This is likely due to the non-judgmental, empathic, and collaborative approach of MI (Miller, Villanueva, Tonigan, & Cuzmar, 2007), whereby adolescents’ own values, opinions, and arguments for change are emphasized and reflected as part of the therapeutic discussion.

MI approaches have typically been delivered in one-on-one (i.e., individualized) interventions and only recently has this approach been used in group settings with youth (D'Amico, Feldstein Ewing, et al., 2010; Wagner & Ingersoll, 2012). Currently, there is only one published randomized controlled trial (RCT) that has examined MI in a group setting with at-risk youth. This study included a single-session of group motivational enhancement therapy (MET) to augment an intervention targeting risky sexual behavior among youth (n=484) in detention centers (Schmiege, et al., 2009). MET is an adaptation of MI that includes one or more sessions in which normative feedback is presented to the client and discussed in an explicitly non-confrontational manner (Miller, 2000). In this study, youth randomized to the augmented intervention received an additional component addressing risky alcohol use and its relation to sexual risk-taking behavior. Youth were provided with feedback regarding their alcohol use. Fidelity checks were conducted throughout the study to ensure that the intervention material was covered and that facilitators were using MET. Three-month outcome data revealed that youth who received the session with the MET component showed greater reductions in sexual risk behavior compared to youth in a control group that only received the sexual risk reduction intervention (Schmiege, et al., 2009), suggesting the efficacy of group MI to reduce risk behaviors.

Another small quasi-experimental study conducted group MI among adolescents and young adults ages 14–20 who were receiving treatment for substance abuse or dependence (Breslin, Li, Sdao-Jarvie, Tupker, & Ittig-Deland, 2002). They compared youth who sought additional help (First Contact program; n =22) and youth who did not seek additional help (n=28). The First Contact program provided four group sessions, including structured feedback, addressing the costs and benefits of change, identifying high-risk situations associated substance use, discussing life goals and how substance use affects the achievement of these life goals, and learning about the “stages of change” concept. They indicated that the intervention was delivered using MI. They found that receiving the First Contact program was associated with reduced use and consequences and increased confidence in high-risk situations up to six months after youth started the program (Breslin, et al., 2002).

Overall, findings using MI with at-risk youth in an individual format have been mixed (Spas, Ramsey, Paiva, & Stein, 2012). Some studies have shown that MI is effective in reducing AOD use and consequences in the short- and long-term (D'Amico, Miles, et al., 2008; Grenard, Ames, Pentz, & Sussman, 2006; Stein, et al., 2011), whereas other studies with at-risk youth have not found any significant effects (Baer, et al., 2007; Thush, et al., 2009). A recent meta-analysis by Jensen et al. that examined 25 studies utilizing individual MI with adolescents age 12–22 found that 11 of the 25 studies had an effect size (ES) of .30 or less (a small effect) and 7 had an ES of .20 or less. Furthermore, this meta-analysis showed that most adolescent MI studies had samples of youth that were mainly white (Jensen, et al., 2011).

The current study adds substantially to the literature in this area by evaluating a group MI intervention, Free Talk (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2010), for an ethnically diverse group of youth with a first time AOD offense. This Stage 1b study (Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001) was focused on (a) understanding client acceptance of Free Talk; (b) determining the feasibility of training facilitators to deliver MI in the group setting by examining and reporting treatment integrity and adherence; and (c) conducting a preliminary evaluation of Free Talk’s efficacy. We expected that youth in Free Talk would find the intervention acceptable and satisfactory compared to usual care (UC) given the extensive testing we conducted of the MI group protocol (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2010). We also expected that facilitators would be able to deliver MI with integrity and adherence in the group setting. We further hypothesized that youth who participated in Free Talk would report better outcomes at three months compared to a UC group on a variety of measures, including past month alcohol and marijuana use, consequences, delinquency, and AOD use before sex. We also collected recidivism data during the year following their initial offense and expected that the Free Talk group would have lower rates of recidivism compared to the UC group.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Setting

We collaborated with the Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse (CADA) in Santa Barbara County. CADA is a nonprofit community-based organization that operates a diversion program called Santa Barbara Teen Court (SBTC) that serves families in south Santa Barbara County. Adolescents who commit a first-time offense and are deemed by the Probation department as not in need of more intensive intervention are offered the opportunity to participate in the Teen Court program in lieu of formal processing in the juvenile justice system. As part of this voluntary program, youth who commit an AOD offense receive six AOD education groups, along with other sanctions (e.g., community service, service on the Teen Court jury, and fees). Adolescents who successfully complete their Teen Court requirements have their AOD offense expunged from their juvenile probation record.

2.2 Design and Randomization

Parents and youth who had agreed to participate in the Teen Court program were recruited to be in the study. To be part of the study, they had to consent and assent to 1) complete surveys and 2) to be randomized to either the MI intervention group (Free Talk) or the usual care (UC) group based on a permuted block randomization procedure. Each group of five participants was randomized 3:2, with 3 teens assigned to the Free Talk group and two teens to the control group. This unequal randomization procedure ensured that there were always a sufficient number of participants in the Free Talk group to allow the group to run successfully. An unequal randomization strategy is appropriate in such circumstances, and has only a small effect on power (Dumville, Hahn, Miles, & Torgerson, 2006). The UC participants in our study attended a group that also included attendees that were not eligible for our study because they did not meet study criteria (e.g., they were under the age of 14; they had a medical marijuana prescription card; or they had a different offense); however, all youth in the usual care group, whether in our study or not reported AOD problems.

2.3 Intervention Condition: Free Talk groups

Free Talk was developed over a one year period using a stage based approach (Rounsaville, et al., 2001) that involved iterative testing of each session to determine feasibility and acceptability of intervention content (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2010). From this testing, we developed a protocol for each of the six sessions. All content was delivered using a MI approach (Miller & Rollnick, 2012; Rollnick, et al., 2008). Free Talk facilitators were four psychology doctoral graduate students at the University of California, Santa Barbara who all had prior experience working with at-risk teens. At the beginning of each session, the facilitator discussed the guidelines and rules for the group (e.g., confidentiality, respect for others in the group) as one would do in any group setting. These guidelines were provided in an MI consistent way (e.g., asking permission to discuss the rules with group members) with the focus on supporting MI adherent actions among the group members (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2012). MI strategies were used in every session to deliver content (D'Amico, Feldstein Ewing, et al., 2010; D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2010). Specifically, the facilitator discussed the pros and cons of continued AOD use versus cutting back or quitting, used willingness and confidence rulers to determine where teens were in terms of wanting to change (or not change) their AOD use, and supported where teens were at in terms of their AOD use. Each session covered different content about AOD use. For example, one session focused on the myths around AOD use (e.g., using alcohol will make me more sociable) and the facilitator reflected concerns teens might have about how their personal beliefs may be affecting their subsequent use. One session focused on discussing with teens their thoughts about the path from no use to experimental use to addiction and how they might make changes to exit this path if they wanted to. Teens also discussed how AOD use might contribute to other risk-taking behavior such as unsafe sex and driving under the influence and the pros and cons of planning ahead and making different choices. Sessions also focused on communication and AOD use, and the facilitator used open ended questions to determine teens’ ideas about how to communicate more effectively. Teens were also provided with information on the effects of AOD use on the brain, and the facilitator engaged the teens using open ended questions and reflections to discuss how the information might affect their personal AOD use in the future. When feedback was delivered briefly in one of the sessions, it mirrored typical information given in feedback reports, such as amount of AOD use by the teen compared to other teens their age, consequences, etc. In all sessions, use of open-ended rather than close-ended questions was emphasized as well as the use of reflective statements. D’Amico, Osilla et al. (2010) provides further information on Free Talk intervention content and delivery. Each session lasted about 55 minutes.

2.4 Control Condition: Usual Care groups

The UC group also consisted of six sessions led by one facilitator employed by the CADA. The curriculum followed an abstinence-based Alcoholics Anonymous approach. Topics included group check-in/discussion of personal triggers, consequences of AOD use, educational videos, discussion of personal experiences with AOD use, and myths about AOD use. Similar to the Free Talk groups, teens could also begin at any session, successfully completed the groups after attending six sessions, and each session lasted about 55 minutes.

2.4.1. Integrity and adherence monitoring of Free Talk and the UC groups

We monitored both groups for MI integrity and collected data on the types of activities that occurred in each session. Free Talk facilitators received approximately 40 hours of MI training prior to facilitating the groups. Training included a one-day workshop on MI, which was delivered by two clinical psychologists affiliated with the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (MINT). In addition, the facilitators were trained on the group session protocol by role-playing each session with feedback from the MINT trainers. All Free Talk groups were digitally recorded and reviewed by the MINT trainers who then provided weekly group supervision for one hour to the facilitators.

We used the Motivational Integrity Treatment Integrity (MITI) Scale (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller, & Ernst, 2010) to assess integrity to MI for both Free Talk and UC groups. Per the MITI protocol, a randomly selected 20-minute segment was coded for each group session (Moyers, et al., 2010). Free Talk sessions were digitally audio recorded and the MITI was used to help monitor the facilitators’ performance and to provide feedback and coaching during supervision. The digital recordings also allowed supervisors to monitor whether there were any problems among group members (e.g., group members acting out, not being respectful) and to ensure that if this occurred that it was addressed during the session. As some youth in the UC groups were not enrolled in the study, these groups could not be digitally recorded; thus each group was evaluated by a trained coder who observed the group in-person and coded a randomly selected 20-minute segment using the MITI.

We also coded both the Free Talk sessions (134) and UC sessions (135) using the Interview Rating guide found in the National Institute on Drug Abuse/Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration manual for clinician adherence and competence (Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter, & Carroll, 2008; NIDA/SAMHSA Motivational Interviewing Blending Team Initiative, 2012) to determine the types of activities and content that occurred in each session. This measure focused on intervention content during each session versus integrity to MI, which was measured with the MITI. Specifically, for this measure, coders rated the entire session and assessed the extent to which the facilitator discussed his/her personal use of alcohol or drugs, the percent time that videos or movies were utilized, how often there was an emphasis on abstinence, whether the facilitator asserted authority, and whether the facilitator provided skills training.

Four raters received approximately 40 hours of training on both the MITI and the Interview Rating Guide. This included practice coding assignments (http://casaa.unm.edu/codinginst.html). Similar to other studies (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005; Tollison, et al., 2008), raters met weekly to discuss discrepancies. All UC and Free Talk sessions were coded by at least one rater, with 85 (27%) of the FT and UC sessions coded by two raters and 46 (15%) Free Talk sessions coded by three raters. We did not have three raters code UC sessions, given that these groups were coded “live” and this would have been disruptive to the group process. Inter-rater agreement levels were good over the course of the study and the raters were in fairly close agreement (for MITI global ratings, raters were within 0.5 points, for behavioral counts, raters were within 3–5 points) (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2012).

2.5 Participants and Recruitment

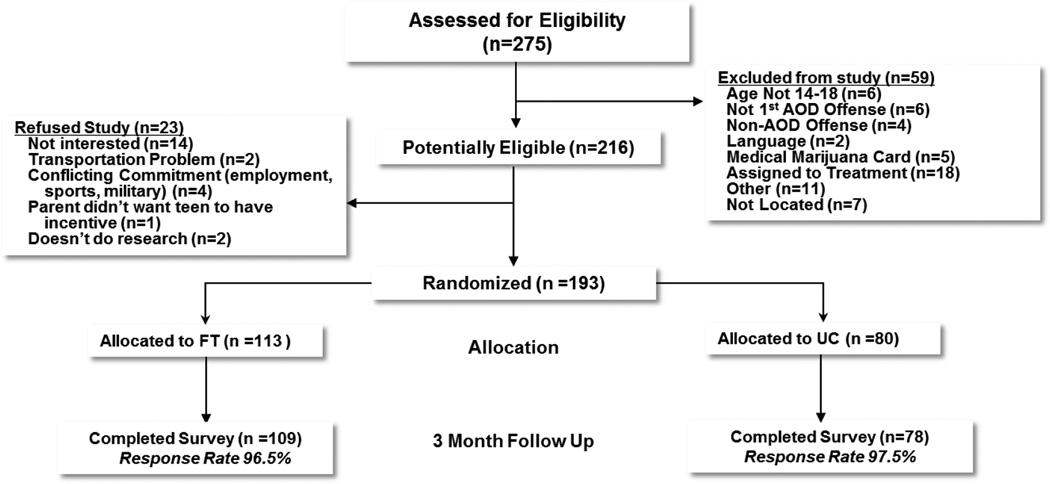

Between January 2009 and October 2011, 275 teens were screened for the study. We recruited teens aged 14–18 that had been referred to Teen Court for a first-time alcohol or marijuana offense. Teen court received approximately 1–15 referrals per month for an average of 8 teens per month and a total of 96 teens per year. Those parents and teens who agreed to participate in the study had to consent/assent to 1) teens completing surveys and 2) teens being randomized to either Free Talk or UC. Of the teens screened for the study, 59 were excluded (see Figure 1). We excluded teens that did not speak and read English well enough to complete the self-administered surveys or had a medical marijuana prescription card. Others were excluded because they were determined by Teen Court staff to need more intensive treatment or they were unlocatable. Of those that were eligible (n = 216), 193 were randomly assigned to the Free Talk or UC condition. Twenty-three parents/youth (11%) refused to participate in the study. The most common reason for refusal was lack of interest or time.

Figure 1.

Study enrollment and data collection

2.6 Procedure

All project procedures were approved by the institution’s Internal Review Board and we received a National Institute of Health Certificate of Confidentiality to protect participant privacy. Parents were required to provide consent for their adolescent to participate (if they were under 18) and youth had to assent. All teens that met study criteria and were scheduled to participate in Teen Court during the study recruitment period were approached by project staff. Teens were asked if they wanted to be part of a project focused on testing a new group program about AOD use. They were told that the project involved completing surveys and being randomized to a new group or a UC group. Participants completed a baseline survey before they attended a Teen Court hearing where they received their sentence; participants completed another survey approximately three months after they completed six AOD education group sessions or approximately 180 days from the time of the baseline interview. Participants were paid $25 for completing the baseline survey and $45 for completing the three-month follow-up survey.

Participants were referred to the AOD education groups once they had their Teen Court hearing and received a sentence to attend the groups. Teens were not paid for the groups as this was part of their sentence. The groups allowed rolling admission; thus each session could stand alone without a teen having to complete a previous session—that is attending session 2 did not require information from session 1. For example, some teens entered the program beginning with session 5 and ending with session 4, whereas others started the program with session 1 and ended with session 6. Thus, teens did not have to wait to enter the program and could begin as soon as possible.

As part of the Teen Court contract, teens had 90 days to complete all six AOD group sessions, and 95% of teens completed their sessions within this time frame. In addition, as part of the Teen Court contract, all teens were randomly drug tested throughout the time that they were attending the group sessions by Teen Court staff. Our study was not provided with drug test results because data were collected by the Teen Court and were therefore confidential.

2.7 Measures

2.7.1 Client acceptance

Satisfaction and quality of services

At the end of the groups, participants reported on the quality and satisfaction with Teen Court services (Larsen, Atkinson, Hargreaves, & Nguyen, 1979). Teens also reported on therapeutic alliance with three items (the group leader and I worked together to set goals; the group leader and I respected each other; things we did in group will help me to make the changes I want) (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006), and on session style (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2010) with two items (the group leader respected where I was at with my AOD use; the group leader valued my opinion). The quality item ranged from 1 (poor) to 4 (excellent); the satisfaction item ranged from 1 (quite dissatisfied) to 4 (very satisfied); all other items were rated on a 1 to 5 scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

2.7.2 MI Integrity and Clinician Adherence and Competence

Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Scale

The MITI is a widely used instrument for coding competency and adherence to MI (e.g., Moyers, et al., 2005; Tollison, et al., 2008; Turrisi, et al., 2009). The MITI is used to assess the facilitator’s behavior during a session and focuses solely on the facilitator’s behavior; thus the MITI can easily be utilized to assess a group facilitator’s behavior (e.g., D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2012; Engle, Macgowan, Wagner, & Amrhein, 2010). Version 3.1 of the MITI has five global scales (collaboration, empathy, evocation, autonomy/support, and direction) that are scored on a scale from 1 (low) to 5 (high). MITI competency is defined as a mean of 4 on the global ratings (Moyers, et al., 2010). As noted in the MITI manual, collaboration occurs when there is little power differential, there is agreement on goals, and clients are encouraged to share the talking. Empathy occurs when the facilitator expresses client understanding and attempts to understand client point of view. Evocation occurs when the facilitator encourages clients to brainstorm reasons and ideas for how to change. Autonomy/support occurs when the facilitator emphasizes and supports client's personal choice. Direction occurs when the facilitator exerts influence on the session and generally does not miss opportunities to direct client toward the target behavior or referral question (Moyers, et al., 2010). In the group setting, the facilitator responds to group members, thus group members influence the facilitator’s behavior. For example, if a facilitator is not collaborative and does not ask open ended questions, then there will be less participation and less sharing of the talking (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2012). Facilitator responsiveness to group member behavior is captured by the MITI global scores. The rater also counts specific behaviors that occur during each coded segment including open-ended questions, closed-ended questions, MI adherent (e.g., “if it’s ok with you, I’d like to share some information with you”) and non-adherent statements (e.g., “you need to stop drinking”), and simple (e.g., “some of you are ready to make changes”) and complex reflections (e.g., “some of you are hoping that by making changes, things will improve in your lives”). Whereas global scores have a range limit (1–5), behavioral counts have no upper end on the scale; thus these scores can vary by session to a greater degree.

Clinician adherence and competence

Six items from the Interview Rating Guide (Martino, et al., 2008; NIDA/SAMHSA Motivational Interviewing Blending Team Initiative, 2012) assessed whether the group facilitator conducted any of the following behaviors: asserted authority (e.g., making decisions about what is best for teen, such as “you really need to show up on time”), confronted teen (e.g., confronting teens about failures, such as “you need to be honest with yourself”), emphasized abstinence (e.g., abstinence as the only possibility), emphasized teen was powerless or had no control over their substance use (e.g., “if you use again, you will pick up where you left off”), provided skills training (e.g., problem solving techniques, discussion of strategies to prevent use), or provided unsolicited advice or direction giving (e.g., specific suggestions about what teen should do such as “you need to talk to your family about your AOD use.”). In addition, we also measured whether facilitators provided didactics or lecture and whether the facilitators discussed their own personal use of alcohol or drugs. Finally, we measured whether there were disruptions in the group (e.g., teens arriving late, phones ringing, staff interrupting group), videos presented, and how often teens discussed their own use of alcohol or drugs (e.g., “I still smoke marijuana”; “I have made changes in my drinking”). All items were rated on a 1–7 (not at all to extensively) Likert scale depending on how frequent each item happened during the session.

2.7.3 Outcomes

AOD use and consequences

Past month frequency of alcohol and marijuana use were assessed using measures from the RAND Adolescent/Young Adult Panel Study (Ellickson, Tucker, & Klein, 2001; Tucker, Orlando, & Ellickson, 2003), which was developed based on established items and scales from Monitoring the Future (Johnston, et al., 2012) and DSM-IV criteria. Frequency of consumption was assessed by asking “During the past month, how many times [or days] have you tried alcohol [marijuana]?” Respondents were also queried about heavy drinking in the past month by asking how frequently they had drunk “five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours.” A “drink” was defined as one whole drink of alcohol (not including a few sips of wine for religious purposes). Two sets of questions based on DSM-IV criteria addressed whether adolescents had experienced consequences due to alcohol or marijuana use (Tucker, et al., 2003). There were 6 items for alcohol (e.g., missed school or work, passed out) and 5 for marijuana (e.g., got into trouble at school or home, had difficulty concentrating). Both scales average responses across items that are rated on a 4-point scale (never, 1 time, 2 times, 3 or more times) and are reliable with adolescents (α = .77 for marijuana and α = .81 for alcohol).

Delinquency

Delinquency was assessed using a 10-item scale that asked teens how often they participated in undesirable behaviors (e.g. cheated on a test at school, been drunk or high in a public place) in the past year or since the last survey (Ellickson, McCaffrey, Ghosh-Dastidar, & Longshore, 2003; Ellickson, Tucker, Klein, & Saner, 2004). Each item ranged from 1 (not at all) to 6 (20 or more times). The ten items were summed to create a scale that ranged from 10 to 60 (α = .70).

AOD use before sex

One item from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012) assessed whether the youth had used AOD before sex. Responses were: I have never had sexual intercourse, yes, or no.

Recidivism

Recidivism data were obtained from the Santa Barbara County Probation department for the Free Talk and UC groups. Due to legal restrictions on identifying minors who have committed crimes, we were not allowed access to individual information about who recidivated. Rather data about the total number of youth who recidivated one year after their first offense for the Free Talk and UC groups was shared. We also examined recidivism rates for a subgroup of youth in each condition that completed all six group sessions.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Satisfaction and quality of services

For the quality item, we compared the percent of teens between the Free Talk and UC groups who reported “excellent”; for satisfaction with Teen Court services, we compared the percent of teens who reported “very satisfied.” For therapeutic alliance and session style, we compared the percent of adolescents who reported “strongly agree”. All analyses controlled for age, gender, and race/ethnicity and were analyzed using logistic regression.

MI integrity and clinician adherence and competence

For analysis of MITI scores, we analyzed data at the level of the session, and compared the mean level of each of the MITI scores between Free Talk and UC. For clinician adherence and competence, we compared the mean number of times that different activities occurred during each session between Free Talk and UC.

AOD use, consequences, delinquency and AOD use before sex

Each outcome was compared between groups, controlling for baseline covariates age, gender, race/ethnicity and the baseline measure of the variable of interest. Because of our rolling group design (also called open enrollment) where individuals may join and leave the group at any time, there is no specific ‘group’ structure of teens at any given session (Morgan-Lopez & Fals-Stewart, 2008; Paddock, Hunter, Watkins, & McCaffrey, 2010), and therefore we used methods to calculate appropriate standard errors that account for this non-independence. To do so, we used a multiple membership model (a cross classified model) (Browne, Goldstein, & Rasbash, 2001), in which each session was deemed to be a group, and individuals were assigned a weight for each group they attended, such that each person’s weights summed to 1.0. For the outcome which related to use of alcohol or drugs before sex, a logistic analysis was used. We are not aware of software which would allow us to incorporate a weighted multiple membership logistic model; thus, we did not use the approach for this outcome and will interpret results with caution.

Recidivism

We conducted a chi square test to determine whether the percentage who recidivated were different between the Free Talk and UC group1.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

For the current study, 113 teens participated in the Free Talk group and 80 teens participated in the UC group (see Figure 1). Examples of offenses included possession of alcohol or marijuana, driving under the influence, or driving with an open container. Overall, 67% of teens were male, with 45% of teens reporting Hispanic race/ethnicity, 45% white (non-Hispanic), and 10% mixed and other. The mean age at baseline was 16.6 years (SD = 1.05). There were no statistically significant differences between the groups on these demographic variables. We did, however, find some differences on AOD use despite our randomization procedure, with more teens in the Free Talk group reporting lifetime alcohol use, alcohol consequences, being drunk or high in public, and past 30 day prescription drug use at baseline (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Group mean estimates (standard deviations) or N at baseline and follow-up on outcomes

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Free Talk Mean (SD) |

UC Mean (SD) |

Free Talk Mean (SD) |

UC Mean (SD) |

Est (SE) | 95% CI | d | p |

| Alcohol Use – Past 30 Days | 2.65 (1.72) | 2.31 (1.45) | 2.80 (1.60) | 2.24 (1.40) | 0.38 (0.23) | (−0.07,0.83) | 0.25 | 0.097 |

| Heavy Drinking – Past 30 Days | 2.06 (1.65) | 1.71 (1.29) | 1.95 (1.20) | 1.65 (1.20) | 0.17 (0.21) | (−0.23,0.58) | 0.14 | 0.402 |

| Alcohol Consequences | 1.59 (2.68) | 1.06 (2.33) | 1.24 (2.06) | 0.72 (1.35) | 0.43 (0.33) | (−0.23,1.08) | 0.24 | 0.201 |

| MJ Use – past 30 Days | 3.15 (2.36) | 2.96 (2.22) | 2.75 (1.23) | 2.38 (2.03) | 0.20 (0.32) | (−0.42,0.83) | 0.12 | 0.519 |

| MJ Consequences | 1.27 (2.26) | 0.93 (2.07) | 0.62 (1.30) | 0.64 (1.66) | −0.07 (0.23) | (−0.53,0.39) | −0.03 | 0.772 |

| Delinquency | 15.32 (4.54) | 14.75 (4.29) | 12.67 (3.28) | 12.41 (3.12) | 0.12 (0.41) | (−0.68,0.93) | 0.04 | 0.766 |

| Number Used Alcohol or Drugs Before Sexa | 21 (29.2%) | 13 (24.5%) | 21 (25.3%) | 14 (22.6%) | −0.60 (2.09) | (−4.75,3.55) | NA | 0.775 |

Note:This n is out of the number of teens who reported having sex: N=72 for Free Talk and 53 for Usual Care.

MJ = marijuana.

Cohen’s d is calculated as the estimate of the difference from the multilevel regression divided by the pooled standard error of the two groups at follow up.

3.2. Client acceptance

Satisfaction and Quality of Services

Table 1 provides information on teens’ perceptions of and quality and satisfaction with services, therapeutic alliance and the session style. For quality ratings, 35% of Free Talk teens reported “excellent” compared to 22% of UC teens, p=.047. For overall satisfaction, 40% of Free Talk teens reported “very satisfied” compared to 23% of UC teens, p=.009. Overall, for items measuring therapeutic alliance and session style, teens who reported “strongly agree” ranged from about one-third (the group leader and I worked together to set goals) to more than two-thirds (the group leader valued my opinion). Although we did not find any statistically significant differences on the therapeutic alliance or session style items, Table 2 shows that more teens in the Free Talk group tended to report “strongly agree” on these items, including “the group leader and I respected each other”, “the group leader valued my opinion”, and “things we did in group will help me to make the changes I want.”

Table 1.

Percent of teens endorsing most positive response concerning satisfaction and quality of services

| Free Talk % |

Usual Care % |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Quality How would you rate the quality of services you received from teen court?1 |

35 | 22* |

|

Satisfaction In an overall general sense, how satisfied are you with the services you received from teen court? 1 |

40 | 23** |

|

Therapeutic Alliance The group leader respected where I was at with my AOD use and that change was up to me |

83 | 83 |

| The group leader and I worked together to set goals | 38 | 33 |

| Things we did in group will help me to make the changes I want | 61 | 54 |

|

Group leader style The group leader and I respected each other |

81 | 74 |

| The group leader valued my opinion | 86 | 76 |

Note: for quality, percent reflects teens who reported “excellent”; for satisfaction, percent reflects teens who reported “very satisfied.” P value controls for race, gender and age.

p<0.05,

p<0.01

Table 2.

MITI scores for Free Talk and Usual Care

| Follow-up | Difference | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Free Talk Mean (SD) |

UC Mean (SD) |

Est (SE) |

| Global Scores | |||

| Evocation | 4.54 (0.45) | 2.10 (0.81) | 2.45 (0.08)*** |

| Collaboration | 4.82 (0.36) | 2.51 (0.76) | 2.31 (0.71)*** |

| Autonomy / Support | 4.80 (0.38) | 2.47 (0.79) | 2.33 (0.07)*** |

| Direction | 4.81 (0.32) | 4.10 (0.86) | 0.71 (0.08)*** |

| Empathy | 4.58 (0.46) | 2.87 (0.97) | 1.72 (0.09)*** |

| Behavioral Counts | |||

| Giving Information | 10.69 (4.91) | 11.72 (7.25) | −1.03 (0.73) |

| MI Adherent | 22.36 (6.77) | 8.69 (5.47) | 13.7 (0.69)*** |

| MI Non-Adherent | 0.09 (0.34) | 1.13 (2.31) | −1.04 (0.20)*** |

| Open Questions | 24.8 (7.89) | 7.6 (5.02) | 17.19 (0.73)*** |

| Closed Questions | 14.25 (5.97) | 17.11 (11.03) | −2.86 (1.05)** |

| Simple Reflections | 16.74 (5.83) | 7.60 (5.02) | 9.11 (0.64)*** |

| Complex Reflections | 11.84 (4.36) | 0.74 (1.15) | 11.10 (0.34)*** |

Note: Global scores range from 1 (low) to 5 (high). Competency is considered to be an average score of 4 or above. Behavioral counts do not have an upper bound. Overall, higher behavioral counts on MI adherent, open ended questions, and simple and complex reflections are associated with greater use of MI strategies (Moyers, et al., 2010).

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<.001

3.3 MI integrity and clinician adherence

MITI mean scores (along with SDs) are shown in Table 2. The difference between the means, along with the standard error and p-value are also shown in the table. The Free Talk and UC groups were significantly different on all MITI scores in the expected direction. The only exception was for “giving information”, in which we did not anticipate significant group differences because both groups focused on providing some education. Scores indicated that a higher MI-consistent style was observed in the Free Talk compared to the Usual Care group. For example, on the global counts measure that ranges from 1–5, Free Talk scored between 4 and 5 while Usual Care scored between 2 and 3. Similarly, the Free Talk facilitators had higher counts of MI-consistent behaviors, including reflections and open ended questions compared to UC.

Table 3 provides information on the types of activities that occurred during each group session for Free Talk and UC. The Free Talk groups were significantly higher on two activities: skills training and teens’ discussion of personal AOD use. The UC groups were significantly higher on all other activities: asserting authority, confrontation of denial and defensiveness, didactics/lecture, disruptions during group, emphasis on abstinence, facilitator discussion of personal AOD use, discussion of legal issues, discussion of powerlessness and loss of control over AOD, unsolicited advice or direction giving, and showing videos.

Table 3.

Clinician adherence and competence during each group session

| Free Talk | Usual Care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | tValue |

| Asserting authority | 1.26 | 0.46 | 2.74 | 1.18 | −13.57*** |

| Confrontation of denial and defensiveness | 1.01 | 0.10 | 1.09 | 0.40 | −2.23** |

| Didactics/lecture | 1.11 | 0.43 | 2.97 | 1.79 | −11.71*** |

| Disruptions in middle of group | 2.04 | 0.87 | 3.26 | 1.34 | −8.83*** |

| Emphasis on abstinence | 1.01 | 0.10 | 1.53 | 0.84 | −7.04*** |

| Facilitator discussed his/her personal use of alcohol and drugs | 1.11 | 0.37 | 4.53 | 1.62 | −23.78*** |

| Legal issues surrounding alcohol and drugs use were discussed | 2.09 | 1.17 | 3.47 | 1.66 | −7.91*** |

| Powerless and loss of control | 1.01 | 0.09 | 1.61 | 0.85 | −8.08*** |

| Skills training | 4.44 | 2.02 | 1.28 | 0.72 | 17.11*** |

| Teens discussed their personal use of alcohol and drugs | 5.04 | 1.48 | 4.40 | 1.42 | 3.60*** |

| Unsolicited advice or direction giving | 1.08 | 0.28 | 3.11 | 1.47 | −15.71*** |

| Videos | 1.00 | 0.00 | 2.55 | 1.62 | −11.04*** |

Note: 1=not at all; 2=a little; 3=infrequent; 4=somewhat; 5=quite a bit; 6=considerably; 7=extensively;

3.4 Outcomes

At the three month follow-up, 187 individuals (97% of the sample) completed the survey. Table 4 shows results for each outcome. For past month alcohol and marijuana use, both groups either maintained or slightly reduced use. Similarly, for alcohol and marijuana consequences, both groups showed a reduced number of reported consequences. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups for use and consequences. We also saw reductions in delinquency for both groups with no significant difference between the groups. Finally, the number of youth who reported using AOD before sex decreased in both groups from 21 youth to 13 youth (Free Talk) and from 21 youth to 14 youth (UC) youth at the three month follow-up. Recidivism data for the groups indicated that just over 1 in 4 teens (28%) in the UC group committed an offense within one year following their first offense compared to a little over 1 in 5 teens in the Free Talk group (22%). The odds ratio was 0.63 (95% CI = 0.30, 1.12; p=.218). Among youth who completed all six sessions, still a little over 1 in 4 youth in the UC group had committed another offense (28%) whereas less than 1 in 5 (19%) among the FT group committed an offense (odds ratio = 0.59; 95% CI = 0.28, 1.23; p = 0.157).

4. Discussion

The current study takes an important first look at group MI for at-risk adolescents and examines client acceptance, feasibility and preliminary outcomes. Our findings highlight that not only is it feasible to conduct MI in an adolescent group setting with high integrity as noted by MITI scores, but also that an MI approach garners greater acceptance from adolescents than usual care, and youth feel that the quality of the MI group is superior compared to usual care groups. Youth who received Free Talk also tended to strongly agree with items such as feeling respect from the group leader and feeling like their opinion is valued. Overall, this suggests that Free Talk created a more satisfying experience for teens in which the guiding approach of MI gave them an opportunity to safely discuss their views on what change might look like for them and to feel that their voice was heard and respected in this setting.

In terms of what actually occurred in the group sessions, significant differences emerged between the UC and MI groups concerning group content. Specifically, adherence data indicated that the MI groups had more discussion of skills training, such as discussion of how to make choices that did not involve AOD use, and also included more discussion of adolescents’ personal AOD use, such as whether or not they were ready to make changes in their AOD use, and how they might go about making those changes if they wanted to take that next step. In contrast, the UC group content had a more confrontational approach, tended to utilize more didactic techniques, provided more advice giving, and had more discussion of abstinence only and powerlessness and loss of control. In sum, both observers and youth in the groups reported different experiences related to both session content and style of the group, emphasizing that the MI group looked and felt very different from the UC group. It is important to note that the UC group had to be coded by live observation; thus, it is possible that some information was missed or that observing a live interaction might affect coding. However, raters coded both Free Talk and UC with one pass and there was good reliability with both the live and audio recorded coding (D'Amico, Osilla, et al., 2012); thus, we feel confident that raters captured most of the behaviors during the UC sessions. In addition, it was necessary to use different facilitators in the Free Talk and UC groups to avoid contamination. Although using the same facilitators would have increased power as we could have controlled for facilitator effects, it would be extremely difficult for a facilitator trained in MI to use a non-MI approach when leading the UC group.

Although group work is often a practical and economical approach, some research has suggested that group work for youth may be iatrogenic (Dishion, McCord, & Poulin, 1999; Kaminer, 2005; Shapiro, Smith, Malone, & Collaro, 2010), which may be due, in part, to youth responding positively in the group setting to bravado about use, such as “I’ll never quit” or “smoking pot is a good way to relax” (Engle, et al., 2010), and in part, to how the facilitator may respond to these situations. For example, facilitator empathy is strongly associated with positive commitment language (e.g., “I am quitting for the summer”) in the group setting (Engle, et al., 2010). Our analysis of preliminary outcomes showed that over time, both groups tended to reduce their AOD use, delinquency, and AOD use before sex. These findings are particularly important given that youth in these groups were at-risk: they were referred to participate due to an earlier AOD offense. Often, these are the types of groups where one might expect to see iatrogenic effects (Dishion, Bullock, & Granic, 2002; Shapiro, et al., 2010). In fact, some might speculate that the MI approach, which encourages youth to talk about their AOD use in the group setting could potentially lead to more AOD use as it could provide more opportunities for youth to “glorify” their use. One important finding from this research is that although the MI groups provided a forum for teens to discuss their personal AOD use, with some teens indicating a readiness to make changes and others indicating that they were not willing to make changes. Preliminary process data from these groups indicate that having this type of discussion was not associated with iatrogenic effects. For example, use of MI strategies, such as open ended questions and reflections focused on change talk (e.g., “Although you enjoy smoking marijuana, you also mentioned that you would probably do better in school if you smoked less”) significantly increased the positive change talk among the group members (D’Amico, et al., 2013). Findings support our MITI coding data; that is, facilitators in Free Talk skillfully utilized MI with reflections and open ended questions and were not confrontational when teens discussed their AOD use. Overall, results emphasize the importance of providing a safe space for discussion of these issues with a facilitator who is trained to respond effectively and encourage positive change talk language.

This Stage 1b study allowed us to take a first look at how MI in the group setting may affect AOD use and other risk behaviors. Given that this was a pilot study, we had a short follow-up time frame and so our findings only provide a small snapshot in time. It is important to acknowledge that getting into trouble with the police, going to teen court, being sentenced by peers, participating in 6 weeks of classes and getting drug tested is likely a very powerful experience for both teens and parents. Anecdotally, both parents and teens reported that this “teen court experience” made a strong impression on them. Having this kind of “teachable moment” may be enough in the short-term to create some positive change, perhaps because parents increase their monitoring and/or teens cut back on their AOD use because of these intense consequences. Other research has shown, for example, that when teens have this type of intense experience, such as going to the emergency room for an alcohol related incident, that this can have significant effects on subsequent drinking behavior such that teens in all treatment groups decrease their use (e.g., Barnett, et al., 2002; Monti, et al., 2007; Spirito, et al., 2011). In addition, in many studies of MI with at-risk youth, it is not uncommon to find non-statistically significant results between groups (Baer, et al., 2007; Bernstein, et al., 2010; Jensen, et al., 2011; Naar-King, Parsons, Murphy, Kolmodin, & Harris, 2010; Peterson, et al., 2006; Spirito, et al., 2011; Stein, Colby, Barnett, & Monti, 2006). Overall, the effect sizes were small in our study; which is typical of most MI intervention studies with adolescents (Jensen, et al., 2011). Thus, further work is needed to examine effects of Free Talk with a larger sample and with a longer-term follow up period to provide a better indication of the intervention’s effectiveness.

Our recidivism data provide some insight into the long-term effects of the Free Talk and UC groups. Teens in both groups recidivated after one year; however, more than 1 in 4 recidivated in the UC group compared to about 1 in 5 in the Free Talk group suggesting that the MI youth may be doing better in the long-term. These data suggest that future research examining individual-level long-term outcomes would be worthwhile.

Due to the nature of this pilot work, our sample size was small and for many of our measures, such as recidivism and AOD use before sex, we had even smaller numbers of teens, which limited our power to detect differences. Even though we used a randomized design, there were observable differences between the groups that we controlled for in our analyses. However, unobservable differences may still have influenced our outcomes. Future work is needed with larger samples to increase the power to detect effects. Additionally, we had a very rigorous training and supervision protocol to ensure that MI occurred in the group setting, which may not be feasible in real world settings. Research must begin to balance what amount of training and supervision is “enough” to ensure integrity and fidelity of MI for adolescent group work and be realistic for providers in these settings. Finally, all data were self-report, the limitations of which are well-known, although possibly exaggerated (Chan, 2008). In fact, much research has shown that self-report among youth is valid when procedures, such as those used in the current study are implemented, for example, discussing confidentiality and providing a safe and private space to complete the survey.

In summary, this study demonstrates that a group MI intervention is both acceptable and feasible for delivery in community diversion settings for at-risk adolescents. A short-term follow-up showed reductions in AOD use and consequences, but the changes were not significantly different from UC. Twelve month recidivism rates indicated that group MI may reduce recidivism more compared to UC. A longer term follow-up with other comparison groups is warranted as many youth who receive a first time offense for AOD typically do not receive any intervention. A better understanding of the group process (i.e., how peers and facilitators may influence participants) is also needed; we currently have a study underway to examine the effects of facilitator and peer speech on both change and sustain talk in the adolescent group setting. In conclusion, these results contribute to the emerging literature on providing MI in a group setting and support its value for treating at-risk adolescents.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Sarah Feldstein-Ewing and Dr. Angela Bryan for their help in developing content for this intervention. We thank the Council on Alcoholism and Drug Abuse in Santa Barbara, CA, especially Penny Jenkins and Ed Cué for their support of this project. We would also like to thank the facilitators, coders, and survey staff who worked on the project: Kristen Sullivan, Kristin Katz, Cally Sprague, Chelsea Nagata, Amber Clemens, Susana Lopez, Megan Zander-Cotugno, Emily Cansler, Alexa Calfee, Nelly Gonzalez, and Rosie Martinez. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Michael Woodward in formatting the manual and developing the Free Talk logo. The current study was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01DA019938) to Elizabeth D’Amico. Portions of the integrity and fidelity data were presented at conferences and published in a separate paper.

Footnotes

Covariates were not taken into account in the recidivism analyses. Due to legal restrictions about juvenile identification, we were unable to obtain individual level recidivism rates so covariates could not be used in our analyses comparing the two groups.

References

- Aseltine RH, Jr, Gore S. Work, postsecondary education, and psychosocial functioning following the transition from high school. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2005;20(6):615–639. [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Garrett SB, Beadnell B, Wells EA, Peterson PL. Brief motivational intervention with homeless adolescents: Evaluating effects on substance use and service utilization. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:582–586. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Lebeau-Craven R, O'Leary TA, Colby SM, Wollard R, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Predictors of motivation to change after medical treatment for drinking-related events in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:106–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J, Heeren T, Edward E, Dorfman D, Bliss C, Winter M, et al. A brief motivational interview in a pediatric emergency department, plus 10-day telephone follow-up, increases attempts to quit drinking among youth and young adults who screen positive for problematic drinking. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17(8):890–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin C, Li S, Sdao-Jarvie K, Tupker E, Ittig-Deland V. Brief treatment for young substance abusers: A pilot study in an addiction treatment setting. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16(1):10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, Hingson R, Swartzwelder S, et al. Underage alcohol use: Summary of developmental processes and mechanisms: Ages 16–20. [Article] Alcohol Research & Health. 2009;32(1):41–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne WJ, Goldstein H, Rasbash J. Multiple membership multiple classification (MMMC) models. Statistical Modelling. 2001;1:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed on [1/15/09]];Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. 2012 Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbss.

- Chan D. So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? In: Lance CE, Vandenberg RJ, editors. Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences. New York: Psychology Press; 2008. pp. 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Edelen MO, Miles JNV, Morral AR. The longitudinal association between substance use and delinquency among high risk youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Feldstein Ewing SW, Engle B, Hunter SB, Osilla KC, Bryan A. Group alcohol and drug treatment. In: Naar-King S, Suarez M, editors. Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. pp. 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Miles JNV, Stern SA, Meredith LS. Brief motivational interviewing for teens at risk of substance use consequences: A randomized pilot study in a primary care clinic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Osilla KC, Hunter SB. Developing a group motivational interviewing intervention for adolescents at-risk for developing an alcohol or drug use disorder. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2010;28:417–436. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2010.511076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Osilla KC, Miles JNV, Ewing B, Sullivan K, Katz K, et al. Assessing motivational interviewing integrity for group interventions with at-risk adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, Epub ahead of print. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0027987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Tucker JS, Miles JNV, Zhou AJ, Shih RA, Green HDJ. Preventing alcohol use with a voluntary after school program for middle school students: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of CHOICE. Prevention Science. 2012;13(4):415–425. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Houck JM, Miles JNV, Hunter SB, Osilla KC, Ewing BA. What happens during group and does it matter? An analysis of change talk of at-risk adolescents in a teen court setting. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2013;37(s2):276a. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Bullock BM, Granic I. Pragmatism in modeling peer influence: Dynamics, outcomes, and change processes. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:969–981. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F. When interventions harm: Peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist. 1999;54:755–764. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumville JC, Hahn S, Miles JNV, Torgerson DJ. The use of unequal allocation ratios in clinical trials: A review. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2006;27:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Longshore DL. New inroads in preventing adolescent drug use: Results from a large-scale trial of project ALERT in middle schools. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1830–1836. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.11.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. Sex differences in predictors of adolescent smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 2001;20:186–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ, Saner H. Antecedents and outcomes of marijuana use initiation during adolescence. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle B, Macgowan MJ, Wagner EF, Amrhein P. Markers of marijuana use outcomes within adolescent substance abuse group treatment. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein SW, Ginsburg JID. Motivational interviewing with dually diagnosed adolescents in juvenile justice settings. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2006;6(3):218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ford JA. Substance use, the social bond, and delinquency. Sociological Inquiry. 2005;75:109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Ames SL, Pentz MA, Sussman S. Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults for drug-related problems. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2006;18(1):53–67. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2006.18.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher R, Gillaspy J. Development and validation of a revised short version of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychotherapy Research. 2006;16(1):12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1(1):91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sartor CE. The natural course of substance use and dependence. In: Sher KJ, editor. The Oxford handbook of substance use disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CD, Cushing CC, Aylward BS, Craig JT, Sorell DM, Steele RG. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79(4):433–440. doi: 10.1037/a0023992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jofre-Bonet M, Sindelar JL. Drug treatment as a crime fighting tool. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 2001;4:175–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume II: College students and adults ages 19–50. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminer Y. Challenges and opportunities of group therapy for adolescent substance abuse: A critical review. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(9):1765–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen D, Atkinson C, Hargreaves W, Nguyen T. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1979;2:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Sherritt L, Gabrielli J, Shrier LA, Knight JR. Screening adolescents for substance use-related high-risk sexual behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:473–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20(2):137–160. [Google Scholar]

- Manzar A, Cervellione K, Cottone J, Ardekani BA, Kumra S. Diffusion abnormalities in adolescents and young adults with a history of heavy cannabis use. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Copeland J. The adolescent cannabis check-up: Randomized trial of a brief intervention for young cannabis users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;34(4):407–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter T, Carroll KM. Community program therapist adherence and competence in motivational enhancement therapy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96(1–2):37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Slym RL, Strang J. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing compared with drug information and advice for early intervention among young cannabis users. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1809–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Motivational enhancement therapy: Description of a counseling approach. In: Boren JJ, Onken LS, Caroll KM, editors. Approaches to drug abuse counseling. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2000. pp. 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Villanueva M, Tonigan JS, Cuzmar I. Are special treatments needed for special populations? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25(4):63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(8):1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Lopez A, Fals-Stewart W. Analyzing data from open enrollment groups: Current considerations and future directions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SML, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst D. Revised Global Scales: Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1.1) 2010 Retrieved from http://casaa.unm.edu/mimanuals.html.

- Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Murphy D, Kolmodin K, Harris DR. A multisite randomized trial of a motivational intervention targeting multiple risks in youth living with HIV: Initial effects on motivation, self-efficacy, and depression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(5):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA/SAMHSA Motivational Interviewing Blending Team Initiative. Motivational interviewing rating guide: A manual for rating clinician adherence and competence. NIDA, SAMHSA; 2012. http://www.oregon.gov/oha/amh/ebp/fidelity/mi-supv-rate-forms.pdf: [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF. Adolescent heavy episodic drinking trajectories and health in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(2):204–212. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock S, Hunter S, Watkins K, McCaffrey D. Analysis of rolling group therapy data using conditionally autoregressive priors; Vancouver, Canada. Paper presented at the Joint Statistical Meeting; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Coffey C, Lynskey MT, Reid S, Hemphill S, Carlin JB, et al. Trajectories of adolescent alcohol and cannabis use into young adulthood. Addiction. 2007;102(4):607–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson PL, Baer JS, Wells EA, Ginzler JA, Garrett SB. Short-term effects of a brief motivational intervention to reduce alcohol and drug risk among homeless adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:254–264. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege SJ, Broaddus MR, Levin M, Taylor SC, Seals KM, Bryan A. Sexual and alcohol risk reduction among incarcerated adolescents: Mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of a brief group-level motivational interviewing-based intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:38–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro CJ, Smith BH, Malone PS, Collaro AL. Natural experiment in deviant peer exposure and youth recidivism. [Empirical Study Quantitative Study] Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(2):242–251. doi: 10.1080/15374410903532635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spas J, Ramsey S, Paiva AL, Stein LAR. All might have won, but not all have the prize: Optimal treatment for substance abuse among adolescents with conduct problems. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2012;6:141–155. doi: 10.4137/SART.S10389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Sindelar H, Rohsenow D, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Sindelar-Manning H, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Lewander JW, Rohsenow D, et al. Individual and family motivational interventions for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(3):269–274. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LA, Clair M, Lebeau R, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Golembeske C, et al. Motivational interviewing to reduce substance-related consequences: Effects for incarcerated adolescents with depressed mood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Epub ahead of print. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein LA, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM. Enhancing substance abuse treatment engagement for incarcerated adolescents. Psychological Services. 2006;3:25–34. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.3.1.0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern SA, Meredith LS, Gholson J, Gore P, D’Amico EJ. Project CHAT: A brief motivational substance abuse intervention for teens in primary care. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Schweinsburg AD. The human adolescent brain and alcohol use disorders. Recent Developments in Alcoholism. 2005;17:177–197. doi: 10.1007/0-306-48626-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thush C, Wiers RW, Moerbeek M, Ames SL, Grenard JL, Sussman S, et al. Influence of motivational interviewing on explicit and implicit alcohol-related cognition and alcohol use in at-risk adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(1):146–151. doi: 10.1037/a0013789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollison S, Lee C, Neighbors C, Neil T, Olson N, Larimer M. Questions and reflections: The use of motivational interviewing microskills in a peer-led brief alcohol intervention for college students. Behavior Therapy. 2008;2:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Orlando M, Ellickson PL. Patterns and correlates of binge drinking trajectories from early adolescence to young adulthood. Health Psychology. 2003;22:79–87. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Larimer M, Mallett K, Kilmer J, Ray A, Mastroleo N, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:555–567. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner CC, Ingersoll KS. Motivational interviewing in groups. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Roffman RA, Stephens RS, Wakana K, Berghuis J. Motivational enhancement therapy for adolescent marijuana users: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):628–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]