Abstract

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is a eukaryotic cytokine that affects a broad spectrum of immune responses and its activation/inactivation is associated with numerous diseases. During protozoan infections MIF is not only expressed by the host, but, has also been observed to be expressed by some parasites and released into the host. To better understand the biological role of parasitic MIF proteins, the crystal structure of the MIF protein from Giardia lamblia (Gl-MIF), the etiological agent responsible for giardiasis, has been determined at 2.30 Å resolution. The 114-residue protein adopts an α/β fold consisting of a four-stranded β-sheet with two anti-parallel α-helices packed against a face of the β-sheet. An additional short β-strand aligns anti-parallel to β4 of the β-sheet in the adjacent protein unit to help stabilize a trimer, the biologically relevant unit observed in all solved MIF crystal structures to date, and form a discontinuous β-barrel. The structure of Gl-MIF is compared to the MIF structures from humans (Hs-MIF) and three Plasmodium species (falciparum, berghei, and yoelii). The structure of all five MIF proteins are generally similar with the exception of a channel that runs through the center of each trimer complex. Relative to Hs-MIF, there are differences in solvent accessibility and electrostatic potential distribution in the channel of Gl-MIF and the Plasmodium-MIFs due primarily to two “gate-keeper” residues in the parasitic MIFs. For the Plasmodium MIFs the gate-keeper residues are at positions 44 (Y⇒R) and 100 (V⇒D) and for Gl-MIF it is at position 100 (V⇒R). If these gate-keeper residues have a biological function and contribute to the progression of parasitemia they may also form the basis for structure-based drug design targeting parasitic MIF proteins.

Keywords: Macrophage migration inhibitory factor, Giardiasis, SSGCID, X-ray crystal structure, Sulphur SAD phasing, Parasite infections

Introduction

Giardia lamblia is an enteric protozoan parasite responsible for giardiasis, an infection of the small intestines that often causes diarrhea. World-wide, the Center for Disease Control estimates this organism infects more than 2.5 million people annually [1] and the World Health Organization includes giardiasis in their “Neglected Disease Initiative” list [2]. In the United States G. lamblia is the most common parasitic protist [3] with over 19,000 confirmed cases reported in 2008 [4]. The organism is transmitted in the latent cyst stage usually via water contaminated by animal or human fecal waste. It is also transmitted among people with poor fecal-oral hygiene (day-care centers, sexual activity). In the presence of host digestive enzymes and bile, the cysts enter a trophozoite stage and attach to epithelial cells in the small intestines. There, feeding and propagating, the organism manifests the symptoms of the disease (diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, and weight loss) by interfering with nutrient absorption without eliciting a strong inflammatory response [5]. Giardiasis generally is not life threatening and symptoms are not observed in approximately one third of those infected. Symptomatic giardiasis can be self-limiting, however, due to the potential for chronic or intermittent symptoms treatment is recommended [6]. Furthermore, studies in the developing world have shown that children with giardiasis are generally malnourished and develop poorly and underperform in school [7].

Drugs commonly used to treat giardiasis include metronidazole, tinidazole, furazolidone, albendazole, nitazoxanide, paraomomycin, and quinacrine [8]. These drugs belong to six different classes of compounds that work with different mechanisms [6]. Unfortunately, potential side effects associated with these drugs contribute to poor compliance and treatment failure. In turn, there is the fear that poor compliance may lead to drug resistant strains of G. lamblia, and indeed, metronidazole tolerant strains have now been identified. Better compliance could be achieved with new drugs that have less severe side effects and shorter dose schedules. To develop new therapies to treat giardiasis or prevent its transmission it is necessary to better understand the obligate parasitic lifestyle of G. lamblia.

An important window into G. lamblia's lifestyle was opened with the recent sequencing of its genomic DNA [9]. The G. lamblia genome contains 6,470 open reading frames distributed over five chromosomes [9]. Included in its genome is a gene encoding a 114-residue protein that is 30 % identical and 43 % similar to human macrophage migration inhibitory factor (Hs-MIF) [10], a ubiquitous multifunctional protein and major mediator of the innate and adaptive immune response against infectious diseases.

Macrophage migratory inhibitory factor was first identified in 1966 as a cytokine released by activated T-cells [11, 12]. Since then, other types of immune cells (macrophophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophiles) and pituitary cells have been shown to release MIF and the protein has been shown to also have enzymatic [13], hormonal [14], and even chaperone-like [15] activities. As suggested by its name, MIF inhibits the random migration of macrophage in vitro [10]. Additionally, MIF has also been associated with other diverse cellular processes including the modulation of cell differentiation and proliferation [16], cell cycle progression [17], regulation of glucocorticoid activity [14, 18], transcriptional regulation of inflammatory gene products [19], and inactivation of the p53 tumor suppressor factor [20]. Despite the association of MIF with multiple cellular functions, the molecular mechanism and structural basis for these functions are still poorly understood [21, 22]. To date, CD4 [23], CXCR2 [24], Jab-1 [16], and the ribosomal protein S19 [25] are the only functional MIF-binding proteins identified.

The activation/inactivation of MIF is associated with numerous diseases including cancer [26], diabetes [27], cardiovascular disease [28], multiple sclerosis [29], asthma [30], and rheumatoid arthritis [30]. With regards to protozoan infections, it has been observed that Hs-MIF may play either a protective or deleterious role depending on the parasite [31]. Interestingly, DNA coding for MIF proteins have been identified in the sequenced genomes of some other protozoan parasites, including Plasmodium falciparum, the etiological agent responsible for malaria [32]. Moreover, in individuals infected with P. falciparum, parasitic MIF has been identified in the serum [33]. The latter observation, coupled with the importance of Hs-MIF in initiating an immune response and the identification of DNA coding for MIF proteins in the sequenced genomes of some (but not all) protozoan species, has led to the hypothesis that parasitic MIF proteins may play a role in the progression of parasitemia and the evasion of a host immune response [34]. To gain some insights into the possible role of parasitic MIF proteins in malaria infections, crystal structures were previously determined for MIF proteins from P. falciparum (Pf-MIF) [34], Plasmodium berghei (Pb-MIF) [34], and Plasmodium yoelii (Py-MIF) [35] and compared to the structure of Hs-MIF. Following this line of logic we have determined the crystal structure for Gl-MIF and compare it to the structures for Pf-MIF, Pb-MIF, Py-MIF, and Hs-MIF in search of structural differences or similarities that may provide new hypotheses into any biological role Gl-MIF may play during the invasion of its host.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression, and purification of Gl-MIF

The Gl-MIF gene (GL50803_12091) was amplified using the genomic DNA of G. lamblia ATCC 50803 strain and the oligonucleotide primers 5′-GGGTCCTGGTTCGATGCCTTGCGCCATTGTCACCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTGTTCGTGCTGTTTATTAAAACGTGCTGCCATTAAAGCCCC-3′ (reverse) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The amplified Gl-MIF gene was then inserted into the expression vector AVA0421 at the NruI/PmeI restriction sites that provided a 21-residue tag (MAHHHHHHMGTLEAQTQGPGS-) at the N-terminal of the expressed protein [36]. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)-R3-pRARE2 cells (gift from SGC-Toronto, Toronto, ON) using a heat shock method. Uniformly 15N-labeled Gl-MIF was obtained by growing the transformed cells (37 °C) in 500 mL of auto-induction minimal media [37] containing NH4Cl (1.4 mg/mL) supplemented with trace metals and vitamins, MgSO4 (120 μg/mL), and the antibiotics chloramphenicol (30 μg/mL) and ampicillin (100 μg/mL). After the cells reached an OD600 reading of ∼ 1.5, the media was cooled to 25 °C, incubated overnight (∼16 h), harvested by mild centrifugation, and frozen at -80 °C. After thawing and re-suspending in ∼ 35 mL of ice chilled lysis buffer (0.3 M NaCl, 50 mM sodium phosphate, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) brought to 0.2 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, the cells were passed through a pre-chilled (5–10 °C) French press (SLM Instruments, Rochester, NY) three times. Following sonication of the suspension for 60 s, the insoluble cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 25,000g for 1 h in a JA-20 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). The supernatant was passed through a 0.45 μm syringe filter and applied to a Ni-NTA affinity column (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) containing ∼ 25 mL of resin. Using gravity, the column was washed sequentially with 40 mL of buffer (0.3 M NaCl, 50 mL sodium phosphate, pH 8.0) containing increasing concentrations of imidazole (5, 10, 20, 50, and 250 mM). Gl-MIF eluted mainly with the 250 mM imidazole wash. The protein was concentrated to ∼5 mL (Amicon Centriprep-10, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and 1–2 mL aliquots loaded on a Superdex75 HiLoad 16/60 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min to simultaneously further purify the protein and exchange it into crystallization buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM TrisHCl, 1.0 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.1). The peak containing Gl-MIF (retention time of 68 min) was collected and the volume reduced (Amicon Centriprep-10, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) to generate samples in the 4 mg/mL range (Lowry analysis) that were ready for crystal screens and biophysical characterization. The expression clones can be freely obtained from BEI Resources (www.beiresources.org/StructuralGenomicsCenters.aspx).

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

A calibrated Aviv Model 410 spectropolarimeter (Lakewood, NJ) was used to collect circular dichroism data on an ∼0.03 mM Gl-MIF sample in crystallization buffer. Steady-state wavelength spectra were recorded in a quartz cell of 0.1 cm path length at 0.5 nm increments between 200 and 260 nm at 25 °C. The average of two steady-state wavelength spectra, recorded with a bandwidth of 1.0 nm and a time constant of 1.0 s, is reported. This spectrum was obtained by subtracting a blank average spectrum from the average protein spectrum and automatically line smoothing the result using Aviv software. A thermal denaturation curve was obtained by recording the ellipticity at 220 nm in 2.0 °C intervals from 10 to 80 °C (30 s equilibrium after temperature stabilization). A quantitative estimation of the melting temperature, Tm, was acquired by taking the average of a first derivative of the thermal denaturation curve [38] from three separate experiments (new sample for each measurement).

NMR spectroscopy

Data was collected at 20 °C on a Varian Inova-600 spectrometer equipped with a 1H{13C, 15N} triple resonance probe and pulse field gradients.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystallization conditions for Gl-MIF were identified using the Precipitant Synergy screens from Emerald Bio (Bain-bridge Island, WA) and the hanging-drop, vapor-diffusion method. Screens were set-up at room temperature (∼22 °C) using equal volumes (1.5 μL) of protein (∼4 mg/mL) and precipitant. Crystals appeared 2–4 days later under conditions #15 (5 % 2-propanol (v/v), 2 M Li2SO4, 100 mM MgSO4) and #30 (30 % MPD (v/v), 4 % PEG 1,500 (v/v), 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5). Native XRD data was collected from crystals grown in the former condition that were cyro-protected in ∼20 % glycerol (v/v). A single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) data set was collected on similar crystals quickly dipped in precipitant containing ∼20 % glycerol and 1 mM NaI. Crystals were mounted on nylon CryoLoops (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA), flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored under liquid nitrogen. A SAD data set for the iodide soaked crystals was collected on beamline X29 at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory, SAD data) at a long wavelength (1.54 Å) in order to increase the anomalous signal of iodide and sulfur. Data were collected on an ADSC Quantum 315 detector in 0.5° frames over 360 images. A higher resolution data set was collected on beamline 23-IDD at GMCA-AT at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory) at a shorter wavelength (0.97934 Å) on a MAR 300 detector with 0.5° frames over 120 images. Data statistics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. X-ray data and refinement statistics for Gl-MIF.

| Crystal parameters | Iodide | Native |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | I213 | I213 |

| Cell dimensions a=b=c (Å), α=β=γ | 95.6, 90 | 95.55; 90 |

| Data set | ||

| X-ray source | X29A, NSLS | 23-IDD, APS |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.54 | 0.97934 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–2.6 (2.67–2.60) | 50–2.30 (2.36–2.30) |

| Rmerge | 0.044 (0.529) | 0.032 (0.441) |

| I/sigma (I) | 71.0 (9.3) | 33.9 (4.4) |

| Completeness | 100 % (100 %) | 100 % (100 %) |

| # reflections overall | 198,979 (15,450) | 47,688 (6,594) |

| # reflections, unique | 4,744 (359) | 6,594 (494) |

| Multiplicity | 42 (43) | 7.2 (7.3) |

| Phasing statistics | ||

| FOM (PHASER, 50–2.6 Å) | 0.39 | |

| FOM (PARROT, 50-2.6Å) | 0.64 | |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Rwork | 0.223 | |

| Rfree | 0.268 | |

| RMSD bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 | |

| RMSD bond angles (Å) | 1.63 | |

| Ramachandran: | ||

| Preferred (%) | 91 (97.9 %) | |

| Allowed (%) | 2 (2.1 %) | |

| Disallowed | 0 (0 %) | |

| Molprobity clash score | 7.65 (97th) | |

| Molprobity score | 1.75 (97th) |

Structure solution and refinement

Data from the iodide soaked crystal were reduced with XDS/XSCALE [39] to 2.6 Å resolution. The crystals belong to the cubic space group I213. One molecule was estimated per asymmetric unit with Vm=2.6 Da/Å3, corresponding to 52 % solvent. The highly multiple data showed a distinct anomalous signal out to about 3 Å resolution as estimated by SigDano in XSCALE. Using data to 3 Å resolution, PHENIX.HYSS [40] identified eight anomalous sites per asymmetric unit. The sites were refined and phases calculated with PHASER_EP [41] using data up to 2.6 Å resolution. The program PARROT was then used to improve the original 2.6 Å resolution phase set. The Figure of Merit (FOM) increased from 0.39 to 0.64 after this density modification. An initial model was built into this density-modified map using BUCCANEER [42] at 2.6 Å resolution that was then refined against the 2.3 Å native data set using REFMAC5.6 [43]. The model contained 110 residues in three chains and was refined to Rwork=0.27 and Rfree=0.34. In hindsight, one iodide ion and seven sulphur atoms contributed to phasing of the initial structure [43]. Refinement was alternated with manual model building using COOT [44].

Structure validation and deposition

The final model consisted of residues S0 (one residual residue of the purification tag) through E101 with one sulfate ion, one chloride ion, and ten water molecules per protein unit. The quality of the final structure was assessed using Molprobity [45] and a summary of this analysis along with the diffraction data and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1. The atomic coordinates and structure factors are available in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 3T5S.

Results and discussion

Crystal structure and solution state of Gl-MIF

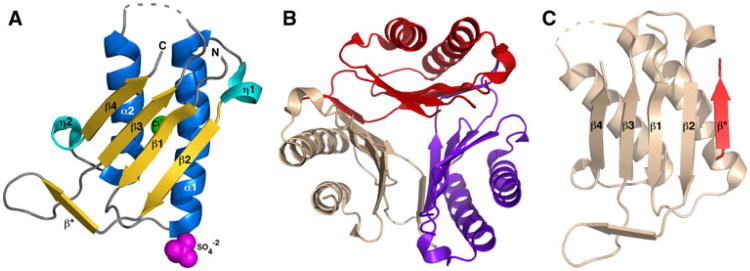

As shown in the ribbon representation of a monomer in Fig. 1a, Gl-MIF adopts an α/β fold composed of a four-strand β-sheet (β2-β1-β3-β4 with the exterior two β-strands parallel and the interior two β-strands anti-parallel) packed against two anti-parallel α-helices. Interpretable electron density was absent for all but the last serine residue (S0) of the 21-residue N-terminal tag, the last 13 residues at the C-terminal (A102 – F114), and a region between β3 and α2 (V67-A71). Electron density could not be fully modeled for the complete side chains of 14 residues, including K14, K30, K34, I65, K72, I76, and K89. While one protein molecule was observed in the asymmetric unit of the Gl-MIF crystal structure, analysis of the inter-subunit interactions with the PDBe PISA server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/prot_int/pistart.html) indicates that the most stable biological unit is a trimer as shown in Fig. 1b. The surface area of the Gl-MIF monomer is 5,414 Å2 while 5,180 Å2 (32 %) becomes buried upon trimer formation. As shown in Fig. 1c, the region between β2 and β3 of one protein unit forms a small β-strand (D47 – F50) that aligns anti-parallel to β4 of the adjacent protein unit to help stabilize the trimer and form a discontinuous β-barrel. Size exclusion chromatography and NMR spectroscopy indicate that the major oligomerization species of Gl-MIF in solution is also a trimer. The predicted molecular weight of Gl-MIF is 14,651 Da. Upon application to a Superdex75 size exclusion column the major band eluted with a retention time of 68 min, a value more inline with a ∼45 kDa trimer than a ∼ 15 kDa monomer under the conditions employed. A solution oligomerization state greater than a monomer was supported by NMR spectroscopic data. The 1H–15N HSQC spectrum for an ∼ 1 mM sample of 15N-labelled Gl-MIF (data not shown) consisted of broad, poorly resolved cross peaks characteristic of a large molecular weight species.

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of the macrophage migratory inhibitory factor (MIF) from Giardia lamblia. a Ribbon representation of a single molecule of Gl-MIF in the asymmetric unit of the crystal. The elements of secondary structure are labelled and coloured marine (α-helix), cyan (310-helix (η)), and gold (β-strand). The sulfate and chloride ions are shown as spheres coloured magenta and green, respectively. The dashed grey line represents a region of the protein with no interpretable electron density suggesting the region is disordered. b The biological relevant Gl-MIF trimer viewed down the three-fold axis with each protein subunit coloured red, wheat, and purple. c Example of the intermolecular β-strand formation between two protein units in the trimer

Circular dichroism profile and thermal stability of Gl-MIF

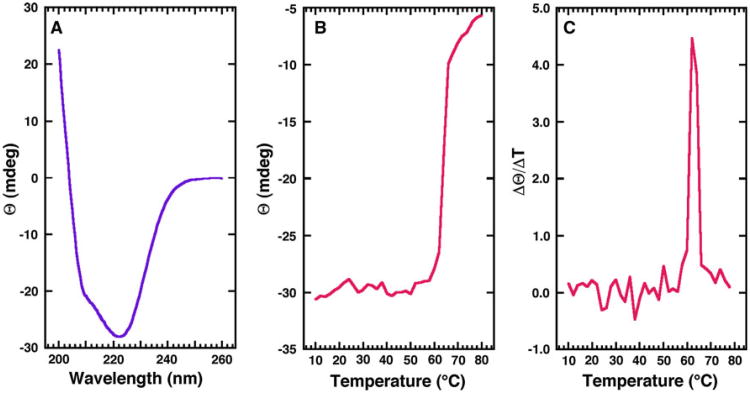

The crystal structure of Gl-MIF shows that the protein is composed of a mixture α-helical and β-strand secondary structure elements. The far-UV CD spectrum for Gl-MIF obtained in crystallization buffer at 25 °C, shown in Fig. 2a, suggests a similar mixture of secondary structure elements exists in solution. The dominant feature of the spectrum is a double minimum at 222 and 208–210 nm and an extrapolated maximum around 195 nm. Such features suggest the presence of α-helical secondary structure in the protein [38, 46]. However, the magnitude of each band of the double minimum is substantially uneven, suggesting a significant contribution of β-strand features to the spectrum [47].

Fig. 2.

Steady-state circular dichroism profile and thermal stability of Gl-MIF. a Circular dichroism steady-state wavelength spectrum for Gl-MIF (0.03 mM) in CD buffer collected at 25 °C. b The CD thermal melt for Gl-MIF obtained by measuring the ellipticity at 220 nm in 2.0 °C intervals between 10 and 80 °C. c First derivative of the thermal melt data showing that the protein has a melting temperature of 62.0 ± 0.3 °C

By following the wavelength specific change in the ellipticity of a protein as a function of increasing temperature, the thermal stability of a protein may be measured and the melting temperature (Tm) estimated for the transition between a folded and unfolded state [48]. As shown in Fig. 2b, the ellipticity at 220 nm is essentially unaffected by temperature from 10 to ∼58 °C followed by a rapid increase in ellipticity that begins leveling-off at ∼65 °C. Visual inspection of the sample after heating to 80 °C shows evidence for protein precipitation, indicating that the unfolding transition is irreversible and the CD data cannot be analyzed thermodynamically [48]. However, a quantitative estimation of the Tm may still be obtained from the CD data by assuming a two-state model and taking a first derivative of the curve shown in Fig. 2b [38]. The average maximum of this first derivative, shown for one trial in Fig. 2c, is 62.0 ± 0.3 °C. A Tm of 79 °C has been reported for Hs-MIF [21], a protein that also irreversibly unfolds upon heating, suggesting that Gl-MIF is thermodynamically less stable than Hs-MIF. The physical basis for the Tm difference may be the greater buried surface area in the Hs-MIF trimer (6,480 Å2) relative to the Gl-MIF trimer (5,180 Å2). If this difference in melting temperature between Gl-MIF and Hs-MIF has any biological significance under physiological temperature (37 °C) and conditions, then one consequence may be a slightly greater population of Gl-MIF in the monomeric state relative to Hs-MIF. Recently, considerable size heterogeneity has been reported for native bovine MIF isolated from brain tissue [49] and it has been suggested that the different cellular functions of MIF may be related to the oligomeric state of the protein [22]. If this hypothesis turns out to be true and Gl-MIF can mimic some of the biological functions of host MIF, then the response affected by Gl-MIF in the host may be modulated by differences in the oligomeric state of Gl-MIF and contribute to the progression of parasitemia. Hence, a potential drug strategy may be to design agents that alter the oligomeric state of the host or parasitic MIF proteins.

Comparison to Hs-MIF and Plasmodium-MIF structures

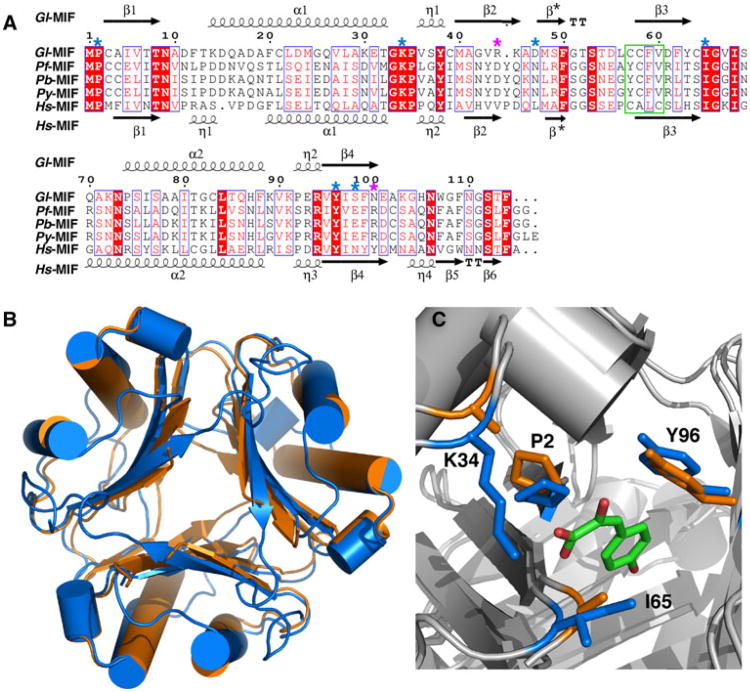

The amino acid sequences of Gl-MIF and Hs-MIF are 30 % identical and 44 % similar (Table 2). The secondary structure elements for Gl-MIF and Hs-MIF, respectively provided above and below their sequence alignment in Fig. 3a, suggests that the topology of both proteins is similar. This is apparent in Fig. 3b, a superposition of the trimeric structures of Gl-MIF (3T5S) and Hs-MIF (1MIF). All the major elements of secondary structure generally overlap and the pairwise RMSD between the Cα positions in the two structures is 1.81 Å (Table 2). Likewise, while the amino acid sequence of Gl-MIF and the other Plasmodium MIF structures are 25–30 % identical and 42–43 % similar, the pairwise RMSD between the Ca positions in Gl-MIF and each Plasmodium-MIF structure vary from 1.55–2.69 Å (Table 2) indicating that the gross features of these structures are similar.

Table 2. Pairwise RMSD difference between the Cα positions in Gl-MIF and other MIF trimer structures.

| Protein | PDB-ID | Identity/similarity (%) | RMSD (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hs-MIF | 1MIF | 30/44 | 1.81 |

| Pf-MIF | 2WKF | 25/43 | 2.48 |

| Pb-MIF | 2WKB | 28/42 | 2.69 |

| Py-MIF | 3GAD | 30/43 | 1.55 |

Fig. 3.

Sequence alignment of selected MIF proteins and structural comparison. a ClustalW2 amino acid sequence alignment of MIF proteins from G lamblia, P. falciparum, P. berghei, P. yoelii, and H. sapiens illustrated with ESPript [55]. Red shaded regions highlight invariant residues in the alignment with invariant and conserved residues inside a blue box. Key, evolutionarily conserved residues necessary for tautomerase activity are indicated by a blue asterisk above the Gl-MIF sequence. Position of the two gate-keeper residues is indicated with a purple asterisk above the Gl-MIF sequence. The oxidoreductase motif in Hs-MIF in outlined with a green box. b Superposition of the ribbon representations of the crystal structures of the Gl-MIF (3T5S, orange) and Hs-MIF (1MIF, blue) trimers. c Superposition of the crystal structures of Gl-MIF (3T5S) and Hs-MIF bound to p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (HPP) (1CA7) highlighting the side chains of four of the important substrate binding residues (P2, K34, I65, Y96 in Gl-MIF) of the tautomerase site. The HPP is coloured by atom type (green = carbon, red = oxygen) and the Gl-MIF and Hs-MIF residues coloured orange and blue, respectively. The structure were superimposed using the program SuperPose [56]

In addition to its role as a cytokine, the MIF proteins also function as an enzyme. Hs-MIF has two enzymatic activities, oxidoreductase [13] and tautomerase. The physiological relevance of these activities, their physiological substrates, and roles in disease are unknown. The thiol-protein oxido-reductase activity in Hs-MIF is mediated by a C56ALC59 motif. While the equivalent region in Gl-MIF adopts the same structure (Fig. 3a), the sequence (C57CFV60) is not conserved. Consequently, any oxidore-ductase activity in Gl-MIF may be reduced relative to Hs-MIF as observed for Plasmodium-MIF proteins which only contain one cysteine residue in the equivalent region [50]. The keto-enol tautomerase activity is mediated by an N-terminal proline, P2, with the active site lined by evolutionarily conserved residues (highlighted with blue asterisks in Fig. 3a). In Fig. 3c the structure of Gl-MIF is superposed upon the structure of Hs-MIF containing the substrate p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate (HPP) bound to the tautomerase active site. The side chains of all the observable active site residues of Gl-MIF superimpose upon those for Hs-MIF in the “open state” of the protein. This is in contrast to the “closed state” observed in some other MIF crystal structures, such as Pb-MIF, where P2 is located in the area where the substrate, HPP, binds [34]. Note that electron density was not observed for the side chains of two residues in the tautomerse active site of Gl-MIF, K34 and I65, perhaps due to increased motion of these side chains in the absence of a substrate.

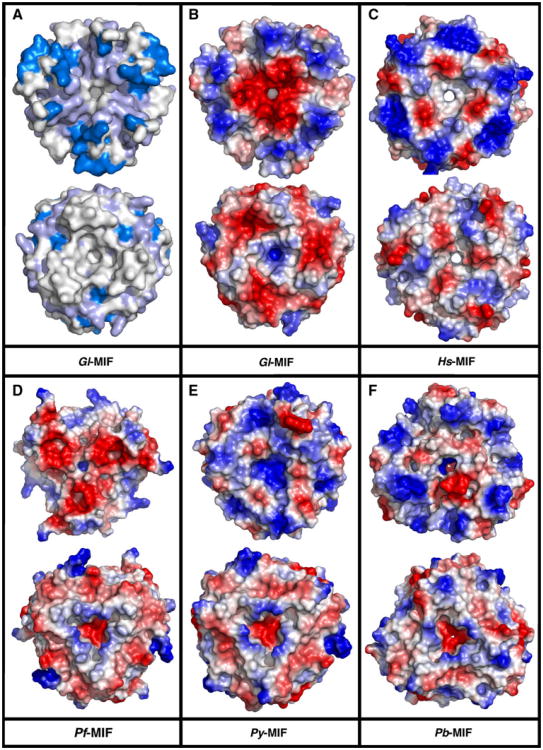

To date a trimer, either in the asymmetric unit or as the biological unit, has been reported for the crystal structure of all other MIF proteins deposited in the Protein Data Bank [34, 35, 51]. A common feature of these trimers is a channel that runs through the center of the complex coincident with the molecular threefold axis. For Hs-MIF it has been speculated that the solvent accessibility and the asymmetric electrostatic potential along this channel's surface may be related to an as yet undiscovered biological function for this channel [51]. These features of the channel are illustrated for Hs-MIF in Fig. 4c, the electrostatic potential at the solvent-accessible surface. A hole through the Hs-MIF trimer is clearly visible with a primarily negative (red) electrostatic potential at both ends. On the other hand, in Gl-MIF (Fig. 4b) the channel is not fully solvent accessible (as measured with Pymol by rolling a sphere of 1.6 Å diameter over the coordinates) and there is a more significant asymmetric distribution of electrostatic potential at both ends of the channel (one side heavily negative and the other side positive). Similarly, the channel in Pf-MIF (Fig. 4d) and Py-MIF (Fig. 4e) is not completely solvent accessible with the accessibility of the channel in Pb-MIF (Fig. 4f) reduced relative to Hs-MIF. Analysis of the structures shows that the side chains of two residues are responsible for reducing the minimal diameter of the channel in Gl-MIF and the Plasmodium MIFs. These two “gate-keepers”, indicated by purple asterisks in Fig. 3a, are residues 44 and 100 (following the Gl-MIF numbering).

Fig. 4.

ClustalW2 summary and comparison of the electrostatic potential at the solvent-accessible surface. Structures are aligned looking through the channel formed by the trimer with both faces shown. In each pair the top structure is the face with the N- and C-termini pointing towards the viewer. a Summary of the ClustalW2 results from Fig. 3a with the invariant residues colored dark blue and the invariant and conserved residues colored light blue. Electrostatic pontential at the solvent-accessible surface for b Gl-MIF (3T5S) c Hs-MIF (1CGQ) d Pf-MIF (2WKF) e Py-MIF (3GAD), and f Pb-MIF (2WKB). Note that electron density is absent at the C-terminus for Gl-MIF (A102-F114) Pf-MIF (N107-G116), Py-MIF (E117, 2 out of 3 chains), and Pb-MIF (F103-S106, 2 out of 3 chains). The missing C-terminal electron density for Py-MIF and Pb-MIF is responsible for the apparent absence of three-fold symmetry in the electrostatic potential pattern in the top face of these two structures

The minimum inter-residue distances at the two gatekeeper sites in all five MIF proteins are summarized in Table 3, At position 44, the site is occupied with a tyrosine residue in Hs-MIF and replaced with an arginine residue in the Plasmodium MIFs with shorter minimum inter-residue side chain separations (3.8–3.6 vs. 5.3 Å) for two out of the three arginines (in Pb-MIF one of the three arginine side chains is “flipped” relative to the other two, creating a larger gap). On the other hand, in Gl-MIF an asparagine residue occupies position 44 with a minimal inter-residue side chain distance similar (5.5 Å) to that observed for Hs-MIF (5.3 Å). At position 100, the site is occupied with a valine residue in Hs-MIF and replaced with a aspartic acid residue in the Plasmodium MIFs with shorter minimum inter-residue side chain separations (4.9–4.3 vs. 6.7 Å). On the other hand, in Gl-MIF an arginine residue occupies position 100 with a much shorter (3.9 Å) minimal inter-residue side chain distance than that observed for Hs-MIF (6.7 Å). In summary, an arginine at position 44 in Pf-MIF and Py-MIF and position 100 in Gl-MIF is the primary residue responsible reducing the solvent accessibility of the channel in Gl-MIF and the Plasmodium MIFs. In the Plasmodium MIFs an aspartic residue at position 100 further contributes to channel constriction. In addition to channel diameter, these amino acid changes also alter the electrostatic potential distribution at both ends of the channel. If the channel in Hs-MIF does have a biological function, perhaps the differences in solvent accessibility and electrostatic potential distribution in Gl-MIF and the Plasmodium-MIFs, due to amino acid differences at positions 44 and 100, contributes to the biological role these parasitic MIF proteins play during invasion of its host. If further studies show this hypothesis to be true, then these differences may form the basis for structure-based drug design targeting parasitic MIF proteins [52].

Table 3. Average minimum heavy-atom distance between “gatekeeper” residues in the channel of Hs-MIF, Gl-MIF, Pf-MIF, Pb-MIF, and Py-MIF.

| Protein | PDB-ID | Residue 44 (X, Å) | Residue 100 (X, Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gl-MIF | 3T5S | N, 5.5 | R, 3.9 |

| Hs-MIF | 1MIF | Y, 5.3 | V, 6.7 |

| Pf-MIF | 2WKF | R, 3.6 | D, 4.6 |

| Pb-MIF | 2WKB | R, 5.8* | D, 4.9 |

| Py-MIF | 3GAD | R, 3.8 | D, 4.3 |

One of the three arginine side chains in the trimer is “flipped” such that there is no three-fold symmetry between the three arginines. Consequently, the “hole” is larger at this site in Pb-MIF

Human MIF has been observed to interact with the CD74 cell surface receptor [21, 23] as do the Plasmodium MIFs Pf-MIF and Pb-MIF [34]. Because antagonists of Hs-MIF-CD74 interactions also inhibit tautomerase activity, the CD74 binding site is inferred to be on the same face of the Hs-MIF trimer [53]. Additional indirect support for this assumption is Consurf [34] and ClustalW2 (Fig. 4a) analyses that show the tautomerase face (top structure each pair in Fig. 4) is the most conserved surface on the MIF trimer. While the molecular details of the MIF-CD74 interface are not known, the structure of the cell surface exposed ectodomain of CD74 is also a symmetric trimer [54] and it has been proposed that this shared three-fold rotational symmetry may play a role in MIF-CD74 interactions [34]. Given the differences in the surface electrostatic potential distributions on the tautomerase face of Hs-Mif, Py-MIF, and Pb-Mif, it is unlikely that electrostatic interactions play a dominant role in MIF-CD74 association.

Summary

The G. lamblia macrophage migration inhibitory factor assembles into a trimer with each monomer adopting an α/β fold composed of two anti-parallel α-helices packed against a four-strand β-sheet. While the general features of the monomer and trimer structure of Gl-MIF are similar to other MIF protein structures, including Hs-MIF and the Plasmodium-MIFs discussed here, there are some differences in the details that arise due to the amino acid sequence non-identity (>70 %) and non-similarity (>56 %) between Gl-MIF and the MIF proteins compared here. Most notable is the minimal diameter of a channel running through the center of the trimer complexes and the electrostatic potential distribution at both ends of the channel that are due to amino acid substitutions at two gate-keeper sites, position 44 and 100. If these and other differences prove to be related to the progression of parasitemia, it may be possible to exploit these differences in structure-based drug design targeting parasitic MIF proteins. However, to properly exploit the Gl-MIF structure presented here, further studies are required to determine if Gl-MIF interacts with the same cellular proteins that Hs-MIF is known to interact with (CD4, CXCR2, Jab-1, and the ribosomal protein S19) and to identify the biochemical mechanism and residues responsible for the association.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Federal Contract number HHSN272201200025C and HHSN272200700057C. The SSGCID internal ID for Gl-MIF is GilaA.00834.a. Part of the research presented here was conducted at the W.R. Wiley Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a national scientific user facility sponsored by U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER) program located at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). Battelle operates PNNL for the U.S. Department of Energy. The assistance of the X29A beam line scientists at the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory is appreciated. Support for beamline X29A at the National Synchrotron Light Source comes principally from the Offices of Biological and Environmental Research and of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy, and from the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- Gl-MIF

Giardia lamblia macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- HPP

p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate

- Hs-MIF

Homo sapien macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- MIF

Macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- Pb-MIF

Plasmodium berghei macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- Pf-MIF

Plasmodium falciparum macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- Py-MIF

Plasmodium yoelii macrophage migration inhibitory factor

- SSGCID

Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease

Contributor Information

Garry W. Buchko, Email: garry.buchko@pnnl.gov, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National, Laboratory, Richland, WA 99352, USA; Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, Seattle, WA, USA.

Jan Abendroth, Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, Seattle, WA, USA; Emerald Bio, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110, USA.

Howard Robinson, Biology Department, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, NY 11973-5000, USA.

Yanfeng Zhang, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National, Laboratory, Richland, WA 99352, USA.

Stephen N. Hewitt, Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 99185-7185, USA

Thomas E. Edwards, Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, Seattle, WA, USA; Emerald Bio, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110, USA

Wesley C. Van Voorhis, Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 99185-7185, USA

Peter J. Myler, Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease, Seattle, WA, USA; Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, Seattle, WA 99109-5219, USA; Department of Medical Education and Biomedical Informatics and Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 99195, USA

References

- 1.Furness BW, Beach MJ, Roberts JM. Giardiasis surveillance–United States, 1992–1997. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2000;49:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savioli L, Smith H, Thompson A. Giardia and Cryptosporidium join the “Neglected Diseases Initiative”. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22(5):203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krappus KD, Lundgren RG, Juranek DD, Roberts JM, Spencer HC. Intestinal parasitism in the United States: update on a continuing problem. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50(6):705–713. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoder JS, Harral C, Beach MJ. Giardiasis Surveillance–United States, 2006–2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2010;59:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farthing MJ. Giardiasis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:493–515. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson LJ, Hanevik K, Escobedo AA, Morch K, Langeland N. Giardiasis–why do the symptoms sometimes never stop? Trends Parasitol. 2009;26(2):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrant RL, Oria RB, Moore SR, Oria MOB, Lima AAM. Malnutrition as an enteric infectious disease with long-term effects on child development. Nutr Rev. 2008;66(9):487–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escobedo AA, Cimerman S. Giardiasis: a pharmacotherapy review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8(12):1885–1902. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.12.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison HG, McArthur AG, Gillin FD, Aley SB, Adam RD, Olsen GJ, Best AA, Cande WZ, Chen F, Cipriano MJ, Davids BJ, Dawson SC, Elmendorf HG, Hehl AB, Holder ME, Huse SM, Kim UU, Lasek-Nesselquist E, Manning G, Nigam A, Nixon JE, Palm D, Passamaneck NE, Prabhu A, Reich CI, Reiner DS, Samuelson J, Svard SG, Sogin ML. Genomic minimalism in the early diverging intestinal parasite Giardia lamblia. Science. 2007;317(5846):1921–1926. doi: 10.1126/science.1143837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lue HQ, Kleemann R, Calandra T, Roger T, Bernhagen J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): mechanisms of action and role in disease. Microbes Infect. 2002;4(4):449–460. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bloom BR, Bennett B. Mechanism of a reaction in vitro associated with delayed-type hydrpersensitivity. Science. 1966;153(3731):80–82. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3731.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David JR. Delayed hypersensitivity in vitro: its mediation by cell-free substances formed by lymphoid cell-antigen interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1966;56(1):72–77. doi: 10.1073/pnas.56.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleemann R, Kapurniotu A, Frank RW, Gessner A, Mischke R, Flieger O, Juttner S, Brunner H, Bernhagen J. Disulfide analysis reveals a role for macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) as thiol-protein oxidoreductase. J Mol Biol. 1998;280(1):85–102. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bucala R. MIF rediscovered: cytokine, pituitary hormone, and glucocorticoid-induced regulator of the immune response. FASEB J. 1996;10(14):1607–1613. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.14.9002552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherepkova O, Lyutova EM, Eronina TB, Gurvits BY. Chaperone-like activity of macrophage inhibitory factor and host innate immune defense against bacterial sepsis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(1):43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleemann R, Hausser A, Geiger G, Mischke R, Burger-Kentischer A, Flieger O, Johannes FJ, Roger T, Calandra T, Kapurniotu A, Grell M, Finkelmeier D, Brunner H, Bernhagen J. Intracellular action of the cytokine MIF to modulate AP-1 activity and the cell cycle through Jab1. Nature. 2000;408(6809):211–216. doi: 10.1038/35041591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takahashi A, Iwabuchi K, Suzuki M, Ogasawara K, Nishihira J, Onoe K. Antisense macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) prevents anti-IgM mediated growth arrest and apoptosis of a murine B cell line by regulating cell cycle progression. Microbiol Immunol. 1999;43(1):61–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calandra T, Bernhagen J, Metz CN, Spiegel LA, Bacher M, Donnelly T, Cerami A, Bucala R. MIF is a glucocorticoid-induced modulator of cytokine production. Nature. 1995;377(6544):68–71. doi: 10.1038/377068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calandra T, Froidevaux C, Martin C, Roger T. Macro-phage migration inhibitory factor and host innate immune defenses against bacterial sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(S2):S385–S390. doi: 10.1086/374752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fingerle-Rowson G, Petrenko O, Metz CN, Forsthuber TG, Mitchell R, Huss R, Moll U, Muller W, Bucala R. The p53-dependent effects of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(16):9354–9359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533295100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El-Turk F, Cascella M, Ouertatani-Sakouhi H, Narayanan RL, Leng L, Bucala R, Zweckstetter M, Rothlisberger U, Lashuel HA. The conformational flexibility of the carboxy terminal residues 105–114 is a key modulator of the catalytic activity and stability of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Biochemistry. 2008;47(40):10740–10756. doi: 10.1021/bi800603x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai F, Asojo OA, Cirillo P, Ciustea M, Ledizet M, Aristoff PA, Leng L, Koski RA, Powell TJ, Bucala R, Anthony KG. A novel allosteric inhibitor of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) J Biol Chem. 2012;287(36):30653–30663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leng L, Metz CN, Fang Y, Xu J, Donnelly S, Baugh J, Delohery T, Chen Y, Mitchell RA, Bucala R. MIF signal transduction initiated by binding to CD74. J Exp Med. 2003;197(11):1467–1476. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernhagen J, Krohn R, Lue HQ, Koenen RR, Dewor M, Georgiev I, Schober A, Leng L, Kooistra T, Fingerle-Rowson G, Ghezzi P, Kleemann R, McColl SR, Bucala R, Hickey MJ, Weber C. MIF is a noncognate ligand of CXC chemokine receptors in inflammatory and atherogenic cell recruitment. Nat Med. 2007;13(5):587–596. doi: 10.1038/nm1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filip AM, Klug J, Cayli S, Frohlich S, Henke T, Lacher P, Eickhoff R, Bulau P, Linder M, Carlsson-Skwirut C, Leng L, Bucala R, Kraemer S, Bernhagen J, Meinhardt A. Ribosomal protein S19 interacts with macrophage migration inhibitory factor and attenuates its pro-inflammatory function. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(12):7977–7985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808620200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bucala R, Donnelly SC. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a probable link between inflammation and cancer. Immunity. 2007;26(3):281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yabunaka N, Nishihira J, Mizue Y, Tsuji M, Kumagai M, Ohtsuka Y, Imamura M, Asaka M. Elevated serum content of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(2):256–258. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.2.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zernecke A, Bernhagen J, Weber C. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117(12):1594–1602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.729125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoi AY, Iskander MN, Morand EF. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a therapeutic target across inflammatory diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2007;6(3):183–190. doi: 10.2174/187152807781696455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calandra T, Roger T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a regulator of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(10):791–800. doi: 10.1038/nri1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Dios Rosado J, Rodriquez-Sosa M. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): a key player in protozoan infections. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7(9):1239–1256. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardner MJ, Hall N, Fung E, White O, Berriman M, Hyman RW, Carlton JM, Pain A, Nelson KE, Bowman S, Paulsen IT, James K, Eisen JA, Rutherford K, Salzberg SL, Craig A, Kyes S, Chan MS, Nene V, Shallom SJ, Suh B, Peterson J, Angiuoli S, Pertea M, Allen J, Selengut J, Haft D, Mather MW, Vaidya AB, Martin DM, Fairlamb AH, Fraunholz MJ, Roos DS, Ralph SA, McFadden GI, Cummings LM, Subramanian GM, Mungall C, Venter JC, Carucci DJ, Hoffman SL, Newbold C, Davis RW, Fraser CM, Barrell B. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2002;419(6906):498–511. doi: 10.1038/nature01097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shao D, Han Z, Lin Y, Zhang L, Zhong X, Feng M, Guo Y, Wang H. Detection of Plasmodium falciparum derived macrophage migration inhibitory factor homologue in the sera of malaria patients. Acta Trop. 2008;106(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dobson SE, Augustin KD, Brannigan JA, Schnick C, Janse CJ, Dodson EJ, Waters AP, Wilkinson AJ. The crystal structures of macrophage migration inhibitory factor from Plamodium falciparum and Plasmodium berghei. Protein Sci. 2009;18(12):2578–2591. doi: 10.1002/pro.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao D, Zhong X, Zhou YF, Han Z, Lin Y, Wang Z, Bu L, Zhang L, Su XD, Wang H. Structural and functional comparison of MIF ortholog from Plasmodium yoelii with MIF from its rodent host. Mol Immunol. 2010;47(4):726–737. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi R, Kelly A, Hewitt SN, Napuli AJ, Van Voorhis WC. Immobilized metal-affinity chromatography protein-recovery screening is predictive of crystallograhic structure success. Acta Cryst. 2011;F67(9):998–1005. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111017374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Studier WF. Production of auto-induction in high-density shaking cultures. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41(1):207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenfield NJ. Using circular dichroism collected as a function of temperature to determine the thermodynamics of protein unfolding and binding interactions. Nat Prot. 2006;6(6):2527–2535. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabsch W. Xds Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr. 2007;40(4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cowtan K. The Buccaneer software for automated model building. 1. Tracing protein chains. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62(9):1002–1011. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906022116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1997;53(3):240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(12):2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WBI, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(2):W375–W383. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holzwarth GM, Doty P. The ultraviolet circular dichroism of polypeptides. J Amer Chem Soc. 1965;87(2):218–228. doi: 10.1021/ja01080a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchko GW, Edwards TE, Abendroth J, Arakaki TL, Law L, Napuli AJ, Hewitt SN, Van Voorhis WC, Stewart LJ, Staker BL, Myler PJ. Structure of a Nudix hydrolase (MutT) in the Mg2+-bound state from Bartonella henselae, the bacterium responsible for cat scratch fever. Acta Cryst. 2011;F67(9):1078–1083. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111011559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karantzeni I, Ruiz C, Liu CC, LiCata VJ. Comparative thermal denaturation of Thermus aquaticus and Escherichia coli type 1 DNA polymerases. Biochem J. 2003;374(3):785–792. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cherepkova O, Gurvits BY. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Identification of the 30-kDa MIF-related protein in bovine brain. Neurochem Res. 2004;29(7):1399–1404. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000026403.06238.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Augustin KD, Kleemann R, Thompson J, Kooistra T, Crawford CE, Reece SE, Pain A, Siebum AH, Janse CJ, Waters AP. Functional characterization of the Plasmodium falciparum and P. berghei homologues of macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Infect Immun. 2007;75(3):1116–1128. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00902-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun HE, Bernhagen J, Bucala R, Lolis E. Crystal structure at 2.6 Å resolution of human macrophage migration inhibitory factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(11):5191–5196. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Myler PJ, Stacy R, Stewart LJ, Staker BL, Van Voorhis WC, Buchko GW. Seattle Structural Genomics Center for Infectious Disease (SSGCID) Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2009;9(5):493–506. doi: 10.2174/187152609789105687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cournia Z, Leng L, Gandavadi S, Du X, Bucala R, Jorgensen WL. Discovery of human macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)-CD74 antagonists via virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2009;52(2):416–424. doi: 10.1021/jm801100v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jasanoff A, Wagner G, Wiley DC. Structure of a trimeric domain of the MHC class II-associated chaperonin and targeting protein Ii. EMBO J. 1998;17(23):6812–6818. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in Postscript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15(4):305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maiti R, van Domselaar GH, Zhang H, Wishart DS. SuperPose: a simple server for sophisticated structural superposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;23:W590–W594. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]