Abstract

The baiji, or Yangtze River dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer), is a flagship species for the conservation of aquatic animals and ecosystems in the Yangtze River of China; however, this species has now been recognized as functionally extinct. Here we report a high-quality draft genome and three re-sequenced genomes of L. vexillifer using Illumina short-read sequencing technology. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that cetaceans have a slow molecular clock and molecular adaptations to their aquatic lifestyle. We also find a significantly lower number of heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms in the baiji compared to all other mammalian genomes reported thus far. A reconstruction of the demographic history of the baiji indicates that a bottleneck occurred near the end of the last deglaciation, a time coinciding with a rapid decrease in temperature and the rise of eustatic sea level.

Despite major conservation efforts, the Yangtze river dolphin, or baiji, is now recognised as functionally extinct. Here, Zhou et al. report a high quality draft baiji genome, as well as three re-sequenced genomes, and highlight evolutionary adaptations to aquatic life.

Despite major conservation efforts, the Yangtze river dolphin, or baiji, is now recognised as functionally extinct. Here, Zhou et al. report a high quality draft baiji genome, as well as three re-sequenced genomes, and highlight evolutionary adaptations to aquatic life.

The baiji, or Yangtze River dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer), is endemic to the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River of China. Nicknamed ‘Goddess of the Yangtze’ or ‘panda in water’, the baiji has become one of the most famous species in aquatic conservation. Unfortunately, this species has experienced a catastrophic population collapse in recent decades due largely to various extreme anthropogenic pressures1. Although great efforts have been made to conserve the baiji, the most recent internationally organized survey, which was conducted in late 2006, failed to identify any living individuals. This led the survey organizers to declare it functionally extinct2.

In addition to being a symbol of conservation, as a fully sequenced genome from the order Cetacea, the baiji genome is also unique in an evolutionary and phylogenetic context. Particularly, cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises), which represent 4% of the mammalian diversity, are adapted to a permanent aquatic life and exhibit with distinctive and highly specialized characteristics including (but not limited to) loss of external hind limbs, echolocation, and changes in respiratory and cardiovascular anatomy and physiology, thereby diverging from the other mammalian orders3,4. Furthermore, paleontological, morphological, and molecular evidence has suggested that cetaceans are nested within Artiodactyla and became secondarily aquatic more than 50 million years ago, accompanied by a long ‘ghost’ lineage, masking the origin of this group of mammals5. Thus, adequate genomic information from this group is critical for understanding the evolutionary history and myriad of adaptations in cetaceans.

Here, using a whole-genome shotgun strategy and Illumina Hiseq2000, we report a draft genome sequence with ~114x coverage for a male baiji. Comparative genomic analyses provide insight into the evolutionary adaptations of cetaceans and the genetic basis underlying the recent demographic decline of the baiji. In addition, the genome provides valuable resources for further research on the biology and conservation of mammals and cetaceans in particular.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly

We applied a whole-genome shotgun strategy to sequence the genome of a single non-breeding male baiji. After filtering low-quality and duplicated reads, 320.87 Gb (approximately114.6-fold coverage) of clean data were retained for assembly (Supplementary Table S1). The genome size was estimated to be 2.8 Gb based on the frequency distribution of 17-base oligonucleotides (17-mer) in the usable sequencing reads and the sequencing depth6 (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S2), which is comparable to cow (2.87 Gb) and horse (2.7 Gb). The final genome assembly was 2.53 Gb (contigs), with contig and scaffold N50, values of 30 kb and 2.26 Mb, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). Approximately 90% of the total sequence was contained in the 1,295 longest scaffolds (>345 kb), with the largest scaffold spanning 11.54 Mb. The assembly metrics of the baiji genome were comparable to those of other animal genomes generated using next-generation sequencing technology (NGS)7 (Supplementary Table S3). The peak sequencing depth was 102-fold and 99% of the genome assembly was more than 50-fold (Supplementary Fig. S2). In general, the average GC content of the baiji was similar to that of other mammals, and all genomic regions with GC contents between 30% and 70% had more than 50-fold coverage (Supplementary Figs S2 and S3). To assess the large-scale and local assembly accuracy of the scaffolds, 17 fosmid library clones were independently sequenced and assembled using shotgun sequencing technology. Most of the fosmid clones were best aligned to only one scaffold, and no obvious misassembly was observed (Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Fig. S4).

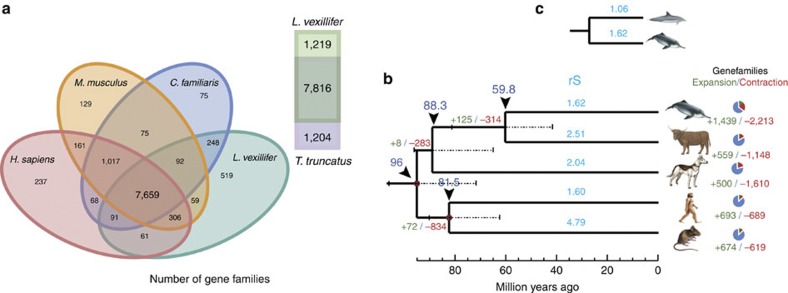

Similar to other well-annotated mammalian genomes, approximately 43% of the baiji genome comprised transposon-derived repeats, and the predicted baiji gene set contained 22,168 genes (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Tables S5–S8). Based on homology approaches, more than 98% of baiji genes showed similarity with functionally known genes of five frequently used databases (Supplementary Table S9). We identified 55,639 recent segmental duplications (SDs) (>1 kb in length,>90% identity) with a total length of 51.3 Mb (~2%) in the baiji genome, which is less than what was observed in human and mouse but more than in giant panda (Supplementary Table S10 and Supplementary Figs S5 and S6). In the baiji genome, genes in SDs were significantly enriched in the gene ontology (GO) terms ‘cytoskeleton’ (GO:0005856, P=6.68 × 10−15, hypergeometric test), ‘GTPase activity’ (GO:0003924, P=2.69 × 10−9, hypergeometric test), and ‘microtubule-based process’ (GO:0007017, P=4.13 × 10−9, hypergeometric test).

Figure 1. Comparison of gene families and the phylogenetic tree.

(a) Venn diagram showing unique and overlapping gene families in the baiji, common bottlenose dolphin, dog, human, and mouse. (b and c) Phylogenetic tree and divergence times estimated for the baiji and other mammals. Numbers associated with each terminal branch in light blue are mean rates of synonymous substitution values (rS). Numbers associated with each branch designate the number of gene families that have expanded (green) and contracted (red) since the split from the common ancestor. Triangle arrows and the numbers under them denote the most recent common ancestor (TMCRA), and the scale units are million years ago. The standard error range for each age is represented by the dashed line. The red solid circles on the branch nodes denote the node as an ‘age constraint’ used in the estimation of the time of divergence.

Substitution rate and turnover of gene families

The rates of molecular evolution vary in different lineages and can be inferred by estimating the rate at which neutral substitutions accumulate in protein-coding genes8. Previous studies have suggested that the point mutation rate has decreased in apes, especially in humans (the ‘hominid slowdown’)9,10, and studies have indicated that whales have a slow molecular clock11. The baiji genome enables an estimation of the rate of neutral substitutions in Cetacea, and Odontoceti in particular, because single copy genes and fourfold degenerate sites were sampled. All terminal lineages have similar mean dN/dS (the ratio of the rate of non-synonymous substitutions to the rate of synonymous substitutions) values except for the baiji (Supplementary Table S11 and Supplementary Fig. S7). The high value of dN/dS in the baiji arose from a low dS rather than a high dN, indicating a comparatively low substitution rate and slower molecular clock in cetaceans. The mean rates of synonymous substitution (rS) along the cetacean lineage (baiji and the bottlenose dolphin) are the slowest among the seven mammalian branches measured (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table S12). Additionally, the rates of synonymous substitution in cetaceans, especially in the baiji, were comparable to that of the human lineage12. The absolute rates for each species also revealed that substitution rates in cetaceans (1.22 × 10−9 substitutions per site per year for baiji and 0.84 × 10−9 substitutions per site per year for the common bottlenose dolphin) were lower than those for the other species in our comparative set and lower than the average mammalian mutation rate13. The mechanistic basis for the mutation rate variation in mammalian genomes is mostly unclear14, and previous studies suggested that lineage-specific rate variation might be correlated with some species-specific biological features, particularly in mammals15. The single variable regressions conducted with the present dataset support the notion that species with greater mass or longer generation times have lower rates of substitution (generation time, rS: slope=−0.71, r2=0.82, P=0.003; body weight, rS: slope=−0.25, r2=0.59, P=0.0274) (Supplementary Table S12).

We determined the expansion and contraction of gene ortholog clusters, which showed that the baiji has undergone twice the amount of variation of in gene families compared with the other mammals examined (Fig. 1b). Among the gene families that underwent the most significant turnover in the baiji, genes involved in oxidoreductase activity (GO:0016491, P=5.54 × 10−54, hypergeometric test), ferric iron binding (GO:0008199, P=1.35 × 10−43, hypergeometric test), metabolic processes (GO:0008152, P=2.04 × 10−10, hypergeometric test), and ATPase activity (GO:0016887, P=2.04 × 10−10, hypergeometric test) were found to have expanded significantly, whereas genes involved in olfactory receptor activity (GO:0004984, P=2.914 × 10−85, hypergeometric test) decreased most significantly. Both changes may be correlated with the basic physiological activities required for underwater living, such as oxygen carrying and sensing. Pseudogenes have also been identified, which were mainly involved in binding (GO:0005488, 63.9%), cell part (GO:0044464, 43.9%), metabolic process (GO:0008152, 41.6%), and catalytic activity (GO:0003824, 33.3%) (Supplementary Table S13 and Supplementary Fig. S8). Many genes associated with pigmentation (GO:0043473, 15.3%) were pseudogenes, which might relate to the overall dull color and simplistic skin pigmentation pattern in the baiji.

PSGs and molecular adaptation in cetaceans

Investigating positively selected genes (PSGs) in the baiji genome can provide insights into the secondary aquatic adaptations of this unique group of mammals. Of the 10,423 1:1 orthologues from the six species shown in Fig. 1b,c, 423 PSGs were found in the baiji lineage and 24 PSGs were found in the common branch to the baiji and dolphin (Supplementary Table S14) using the branch site-mode16 under a conservative 1% false-discovery-rate criterion with a Bonferroni correction of less than 0.01. The relatively large number of PSGs in the baiji could have resulted from a generally higher mean dN/dS along the cetacean lineage (Supplementary Fig. S7). GO classification of the baiji PSGs reflects gene enrichment in protein binding (GO:0005515, P=0.00017, hypergeometric test), cellular process (GO:0009987, P=0.022, hypergeometric test), and intracellular signal transduction (GO:0035556, P=0.036, hypergeometric test). It should be noted that PSGs in the baiji lineage were also involved in DNA repair (GO:0006281) and response to DNA damage stimulus (GO:0006974), which have not been noted in previous analyses of mammals17 or dolphin18,19. Pathways related to DNA repair and damage are known to have a major impact on the development of the brain and have been implicated in diseases such as microcephaly20,21, whereas the evolution of DNA damage pathways might also have contributed to the slowdown of the substitution rate22, which was observed in cetaceans.

In addition to positive selection, the aquatic adaptations of cetaceans could be driven by other functional changes. For example, river dolphins, such as the baiji, have convergently reduced the size of their eyes and the acuity of their vision, likely in response to poor visibility in fluvial and estuarine environments23. Upon examining 209 genes related to vision in humans (GO:0007601: visual perception) in the baiji genome, we identified four genes (OPN1SW, OPN3, ARR3, and PDZD7) that may have lost their function due to a frameshift mutation or premature stop codons (Supplementary Table S15). Of the three essential opsins in mammals, baiji possess the inactivated short wavelength-sensitive opsin (SWS1), functional rod opsin (RH1), and long wavelength-sensitive opsin (LWS), similar to most of the toothed whales24,25.

Odontocete cetaceans have also evolved a complex system of echolocation that involves the production and perception of high-frequency sound under water4. The independent origin of echolocation in toothed whales and echolocating bats is a classic model of convergent evolution26,27. Previous genetic studies have documented parallel sequence evolution and positive selection in five genes in bats and dolphins (SLC26A5, Cdh23, Pcdh15, TMC1, and DFNB59) 26,27,28,29. When combined with the assembly of the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), 74 1:1 orthologs of candidate genes associated with hearing and vocalization were identified and examined in Myotis and the five species in Fig. 1b. To identify genes exhibiting convergent evolution in the baiji and Myotis lineages, the dN/dS of branches leading to echolocating mammals (ω2) were estimated and compared to those of all other branches (ω1) as well as to the average ω across the tree (ω0). Seven genes (including SLC26A5 and TMC1) were found to have evolved under significant accelerated evolution (Table 1), and 17 genes contained parallel amino acid changes in echolocating mammals (Supplementary Table S16).

Table 1. Tests of accelerated and parallel evolution of genes associated with hearing and vocalization in baiji and the little brown bat.

| Symbol | Description | ω0 | ω1/ω2* | P-value† |

Number of sites‡ |

Probability§ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Expected |

Observed | Poisson | JTT | ||||||

| Poisson | JTT | ||||||||

| MMP14 | matrix metallopeptidase 14 (membrane-inserted) | 0.09488 | 0.04293/0.2402 | 3.22E-12 | 0.0209 | 0.0747 | 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| PAX2 | paired box 2 | 0.08193 | 0.01945/0.20917 | 2.10E-07 | 0.0040 | 0.0142 | 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| DZIP1 | DAZ interacting protein 1 | 0.31375 | 0.24442/0.59685 | 2.61E-07 | 0.2659 | 0.9455 | 4 | 0.00017 | 0.01583 |

| TMC1 | transmembrane channel-like 1 | 0.04032 | 0.02007/0.1103 | 3.53E-06 | 0.0107 | 0.0385 | 3 | 0.000 | <0.0001 |

| SLC26A5 | solute carrier family 26, member 5 (prestin) | 0.0953 | 0.05424/0.27278 | 1.88E-04 | 0.0158 | 0.0572 | 2 | 0.000124 | 0.00158 |

| WNT8A | wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 8A | 0.18529 | 0.14991/0.40997 | 3.31E-03 | 0.0454 | 0.1643 | 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| SPARC | secreted protein, acidic, cysteine-rich | 0.03018 | 0.01913/0.06775 | 6.71E-03 | 0.0064 | 0.0232 | 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

*ω2 are dN/dS values for echolocation mammals (baiji and the little brown bat) and ω1 are for the other mammals in the analyses.

†The significance of differences between the alternative and null models was evaluated using likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) by calculating twice the log-likelihood (2DL) of the difference following a chi-square distribution.

‡The number of the parallel evolutionary sites between two lineages compared and the observed number are estimated by comparing the present day and the ancestral sequences inferred by the Bayesian method.

§The probability of parallel–change sites can be explained by random chance.

A previous study revealed that genes encoding sweet, umami, and bitter taste receptors were nonfunctional in the bottlenose dolphin30. We confirmed these results, and further, we discovered that all taste receptor genes in the baiji and dolphin are pseudogenes, with the exception of the salt receptor ENaC, a hetero-oligomeric complex comprising by three homologous subunits (SCNN1A, SCNN1B, and SCNN1G) (Supplementary Tables S17 and S18). Secondarily aquatic amniotes also have reduced olfactory capacity; 248 olfactory receptor (OR) genes can be identified in the baiji genome (Supplementary Table S19), which is less than that in many other mammals31,32. As in other cetaceans, nearly half of the OR genes (49%), as well as TRPC2, are potentially nonfunctional due to frameshifts and/or inserted stop codons. Our results revealed that OR gene family groups 1/3/7 (25%) and 2/13 (23%) had the highest proportion of functional ORs in the baiji, suggesting that these genes might assume other functions in addition to olfaction31. The massive loss of ORs in the baiji genome is consistent with the complete loss of the olfactory bulb or olfactory tract in odontocetes33,34.

Heterozygosity rate and demographic history

The baiji genome provides us the opportunity to investigate what role, if any, the genome played in the functional extinction of this organism. We used the assembled baiji genome sequence as a reference and realigned all usable sequencing reads from all four sequenced individuals. A total of 825,504 and 672,755 heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified with the most relaxed and stringent filters, respectively. Of the 683 genes with SNPs, genes involved in protein complex (GO:0043234, P=0.006, hypergeometric test), plasma membrane (GO:0005886, P=0.02, hypergeometric test), protein binding (GO:0005515, P=4.66 × 10−5, hypergeometric test), and cell adhesion (GO:0007155, P=0.01, hypergeometric test) were significantly enriched. The estimated mean heterozygosity rate of the baiji genomes was 1.21 × 10−4 (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S20), which is approximately 11 times lower than the rate estimated for the panda genome (1.32 × 10−3)35,36, another critically endangered animal, and approximately 6 times lower than that of naked mole rat (0.7 × 10−3) which was recognized as an inbreeding species37. The heterozygosity rate in the X chromosome was about 73% that of the autosomes and Y chromosome, and the transition/transversion ratio was 1.40 (Table 2). To our knowledge, the baiji has the lowest SNP frequency of all other individual mammalian genomes reported thus far. This low frequency could be related to the relatively low rate of molecular evolution in cetaceans; however, considering that the decrease in the rate of molecular evolution in the baiji was not as great as the decrease in the heterozygosity rate, it is likely that much of the low genetic diversity observed was caused by the precipitous decline in the total baiji population in recent decades and the associated inbreeding.

Table 2. Statistics of identified heterozygous SNPs in baiji genomes.

| Type | Mean effective position | Mean heterozygote SNP No. | Mean heterozygote SNP rate ( × 10−3) | Mean transition/transversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome | 2,373,544,701 | 287,948 | 0.121 | 1.24 |

| Autosomes+ChrY | 2,239,847,611 | 275,912 | 0.123 | 1.24 |

| ChrX | 130,245,650 | 11,729 | 0.090 | 1.40 |

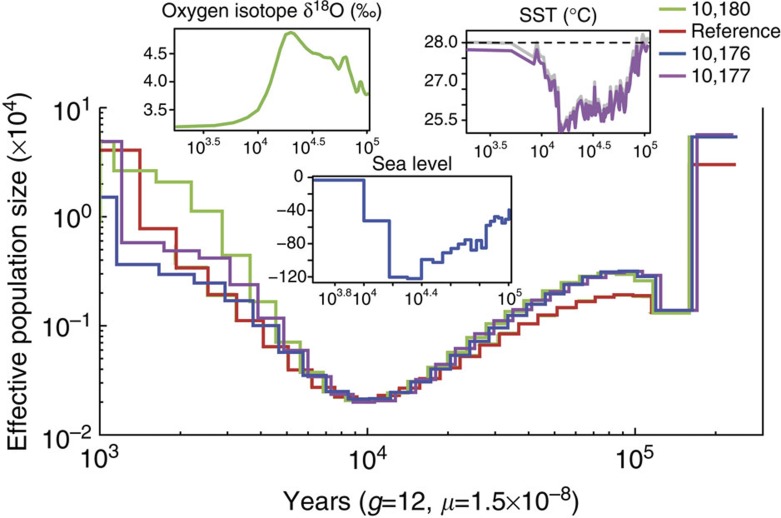

A reconstruction of the population demography of the baiji uncovered a historical bottleneck, which may have contributed to its low level of genetic variability. The pairwise sequentially Markovian coalescent (PSMC) model38 was used to examine the changes in the local density of heterozygotes across the baiji genome and to reconstruct its demographic history. Our analyses uncovered distinct demographic trends from 100,000 to 1,000 years ago (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S9); the baiji experienced a consistent and unidirectional contraction of its population with the smallest effective population size (bottleneck) ~10 thousand years ago (KYA ). The population then expanded to reach its greatest size ~1 KYA. Overall, our reconstructed demographic history correlates well with global climate39 and the Pleistocene and Holocene temperature record of the South China Sea with one major exception40: the nadir of population size postdates the nadir in temperature by approximately 10 KYA. One possible explanation for this inconsistency is that the population size of the baiji was influenced by temperature and rates of sea level rise41. The smallest population coincides with the last deglaciation and the most rapid rises in eustatic sea level over the last 100 KYA (approximately 1–1.5 cm/yr). The rapid rise in sea level would have drowned the Yangtze River valley and led to a dramatic reduction in available freshwater habitats. Once the rate of rise slowed, the now submerged valley would have infilled42, and the resulting decrease in the river gradient would have led to a more complex river system (i.e., meanders, gradients) and new habitats for recovering baiji populations. Regardless of the exact cause(s) of the historical bottleneck, the constant population growth after 10 KYA indicates that the recent declines and eventual functional extinction of the baiji are not a direct consequence of this historical bottleneck but instead were caused by extreme human impacts to the Yangtze River in recent decades1.

Figure 2. Demographic histories of the baiji reconstructed using the PSMC model.

Smoothed curves on the top represent global climate39, sea surface temperature (SST) of South China Sea40, and global sea-level fluctuations41. Horizontal dashed line marks present SST for modern times. The age units for all graphs are years.

Discussion

We found a generally slow substitution rate in cetaceans through genome sequencing of the Yangtze River dolphin and comparative analyses with other mammalian genomes. New insights into potential molecular adaptations to secondary aquatic life were outlined, such as a decrease in olfactory and taste receptor genes, changes in vision and hearing genes, and positive selection on genes related to expansion of the brain.

Notably, baiji genomes have the lowest density of SNPs among the available mammal genomes, which is consistent with the small and rapidly declining population size of this organism. The reconstructed demographic history over the last 100 KYA featured a continual population contraction through the last glacial maximum, a serious bottleneck during the last deglaciation, and sustained and rapid population growth after the eustatic sea level approached the current levels. The close correlation between population trends, regional temperatures, and eustatic sea level suggests a dominant role for global and local climate changes in shaping the baiji’s ancient population demography. Future genetic sequencing from additional individuals would allow for further reconstruction of the demographic history of the baiji, allow us to test our hypothesis regarding the correlation between baiji population dynamics and global climate fluctuations, and uncover the role of genetic factors in the functional extinction of this organism.

Methods

Baiji samples

An adult male baiji that has been stored at Nanjing Normal University at −20 °C since 1985 was chosen for de novo sequencing. One male and two female animals were used for resequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted from abdominal muscle and the quality and quantity of DNA obtained was sufficient for whole-genome sequencing.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Libraries for genomic DNA sequencing were constructed according to the Illumina standard protocol. In total, 22 standard libraries (insert size=180 bp to 20 kb) and one PCR-free library (insert size=350 bp) were constructed and sequenced using an Illumina Hiseq2000. Finally, 503.87 Gb of raw data were generated, and after filtering, 320.8 Gb of data remained for de novo assembly. Whole-genome assembly was performed using SOAPdenovo43, and Gapcloser (version1.12, http://soap.genomics.org.cn/soapdenovo.html) was used to fill gap (N) regions. Additionally, 17 fosmid clones were sequenced using Sanger methods and used as reference data to determine genomic coverage.

Genome annotation and evolution

Interspersed repeats were characterized by homolog-based identification using RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org) and the repeat database, Repbase44. Repeated proteins were identified using RepeatProteinMask, and de novo interspersed repeat annotation was performed using RepeatModeler (http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler.html.). An additional round of RepeatMasker analysis was applied following de novo repeat identification. All repeats identified in this way were defined as total interspersed repeats. Tandem repeats were identified using Tandem Repeat Finder45. Protein sequences from cow, dog, horse, human, mouse, and dolphin were obtained and aligned against the baiji genome assembly using tblastn46. Loci with aligned proteins were extracted, and GeneWise47 was used to predict the gene model. Augustus48, GENSCAN49, and GlimmerHMM50 were used for de novo gene prediction. GLEAN51 was applied to integrate the predicted genes and form the final gene set. To infer gene functions, we searched the final gene set against the protein databases KEGG52, SwissProt53, and TrEMBL54. InterProScan (Pfam, PRINTS, PROSITE, ProDom, and SMART databases) 55 was used to determine motifs and domains in the final gene set.

Phylogenetic analyses and substitution rate

The phylogenetic tree was constructed in MrBayes 3.1.2 (ref. 56) using single-copy orthologous genes (Supplementary Methods). The best-fit model was determined using MRMODELTEST 2.3 (ref. 57). Bayesian molecular dating was adopted to estimate the neutral evolutionary rate and species divergence time using MCMCTREE, implemented in PAML (v. 4.4b)16. Branch-specific evolutionary analyses of selection pressure were conducted on concatenated alignments using the free ratio model of the codeml package in PAML16. The absolute neutral substitution rate per year (nt/years) was estimated under both global58 and local clock models, using baseml within PAML16.

Positively selected genes and demographics

The branch-site model59 was used to detect positive selection along a target branch. We compared Model A1, in which sites may evolve either neutrally or under purifying selection, with Model A, which allows sites to be under positive selection. SOAPsnp (version 1.15)60, which uses a Bayesian statistical model, was used to call heterozygous SNPs in the baiji assembly. The recently developed PSMC model38 was utilized to estimate demographic history using heterozygous sites across the genome.

Author contributions

G.Y. conceived this study, and designed and managed this project. S.X., Y.Y. and G.Y prepared samples. G.F. and J.Z. performed genome sequencing and assembly. X.Z. and G.F. supervised genome sequencing and assembly. B.H. and T.L. performed genome annotation. X.Z., G.F., F.S., K.Z., Z.H., W.Z., H.H., J.C., C.S. Y.F.C., D.Y., Y.C., X.G., H.W. and Z.W. performed genetic analyses. X.Z., G.Y., and G.F. discussed the data. X.Z. wrote the paper with significant contribution from F.S., X.L., X.F., and F.W. All authors contributed to data interpretation.

Additional information

Accession Codes The whole genome sequences have been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank nucleotide core database under the accession AUPI00000000. The version described in this paper is version AUPI01000000.

How to cite this article: Zhou, X. et al. Baiji genomes reveal low genetic variability and new insights into secondary aquatic adaptations. Nat. Commun. 4:2708 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3708 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S9, Supplementary Tables S1-S20, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan H. Geisler and Michael R. McGowen very much for their hard work in preparing the manuscript and molecular analyses. We thank Yongjin Wang and Carles Pelejero for their help in supplying references and the raw data in drawing figure. We thank Qi Wu and Yibo Hu for their valuable suggestions. We thank Li Liao for her assist in management of this project. This project is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 30830016, 31000953, 31172069), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education, the Ministry of Education of China (grant nos. 20103207120010 and 20113207130001), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

References

- Yang G., Bruford M. W., Wei F. & Zhou K. Conservation options for the Baiji: time for realism? Conserv Biol. 20, 620–622 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey S. T. et al. First human-caused extinction of a cetacean species? Biol. Lett. 3, 537–540 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgelard C., Douzery E. & Michaux J. Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Cetacea, Whales, Porpoises and Dolphins Science Publishers, Inc. Enfield: New Hampshire, (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Reidenberg J. Anatomical adaptations of aquatic mammals. Anat. Rec. A 290, 507–513 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Xu S., Yang Y., Zhou K. & Yang G. Phylogenomic analyses and improved resolution of Cetartiodactyla. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 61, 255–264 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. et al. The genomes of Oryza sativa: a history of duplications. PLoS Biol. 3, e38 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Q. et al. The yak genome and adaptation to life at high altitude. Nat. Genet. 44, 946–949 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution Cambridge Univ. Press (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Bromham L., Rambaut A. & Harvey P. H. Determinants of rate variation in mammalian DNA sequence evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 43, 610–621 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Molecular clocks: four decades of evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 654–662 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J. A. et al. Big and slow: phylogenetic estimates of molecular evolution in baleen whales (suborder mysticeti). Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 2427–2440 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M. et al. Phylogenomic analyses reveal convergent patterns of adaptive evolution in elephant and human ancestries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 20824–20829 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. & Subramanian S. Mutation rates in mammalian genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 803–808 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson A. & Eyre-Walker A. Variation in the mutation rate across mammalian genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 756–766 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A. P. & Palumbi S. R. Body size, metabolic rate, generation time and the molecular clock. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 4087–4091 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosiol C. et al. Patterns of positive selection in six mammalian genomes. PLoS. Genet. 4, e1000144 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowen M. R., Grossman L. I. & Wildman D. E. Dolphin genome provides evidence for adaptive evolution of nervous system genes and a molecular rate slowdown. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 3643–3651 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. B. et al. Genome-Wide Scans for Candidate Genes Involved to the Aquatic Adaptation of Dolphins. Genome Biol Evol 5, 130–139 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Driscoll M. & Jeggo P. A. The role of the DNA damage response pathways in brain development and microcephaly: insight from human disorders. DNA Repair (Amst.) 7, 1039–1050 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon P. J. DNA repair deficiency and neurological disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 100–112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten R. J. Rates of DNA sequence evolution differ between taxonomic groups. Science 231, 1393–1398 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillieri G. The eye of Pontoporia blainvillei and Inia boliviensis and some remarks on the problem of regressive evolution of eye in Platanistoidea. Invest. Cetacea 11, 58–108 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Meredith R. W., Gatesy J., Emerling C. A., York V. M. & Springer M. S. Rod monochromacy and the coevolution of cetacean retinal opsins. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003432 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson D. H. & Dizon A. Genetic evidence for the ancestral loss of short-wavelength-sensitive cone pigments in mysticete and odontocete cetaceans. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270, 673–679 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. et al. Convergent sequence evolution between echolocating bats and dolphins. Curr. Biol. 20, R53–R54 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Rossiter S. J., Han X., Cotton J. A. & Zhang S. Cetaceans on a molecular fast track to ultrasonic hearing. Curr. Biol. 20, 1834–1839 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. Y., Liang L., Li G. S., Murphy R. W. & Zhang Y. P. Parallel evolution of auditory genes for echolocation in bats and toothed whales. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002788 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K. T., Cotton J. A., Kirwan J. D., Teeling E. C. & Rossiter S. J. Parallel signatures of sequence evolution among hearing genes in echolocating mammals: an emerging model of genetic convergence. Heredity 108, 480–489 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P. et al. Major taste loss in carnivorous mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 4956–4961 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden S. et al. Ecological adaptation determines functional mammalian olfactory subgenomes. Genome Res. 20, 1–9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowen M. R., Clark C. & Gatesy J. The vestigial olfactory receptor subgenome of odontocete whales: phylogenetic congruence between gene-tree reconciliation and supermatrix methods. Syst. Biol. 57, 574–590 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelschläger H. H. A. & Oelschläger J. S. Brain. In:Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals second ed. Perrin W. F., Würsig B., Thewissen J. G. M. (Eds.)Elsevier (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Kishida T. & Thewissen J. G. Evolutionary changes of the importance of olfaction in cetaceans based on the olfactory marker protein gene. Gene 492, 349–353 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome. Nature 463, 311–317 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of giant pandas provides insights into demographic history and local adaptation. Nat. Genet. 45, 67–71 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E. B. et al. Genome sequencing reveals insights into physiology and longevity of the naked mole rat. Nature 479, 223–227 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. & Durbin R. Inference of human population history from individual whole genome sequences. Nature 475, 493–496 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachos J., Pagani M., Sloan L., Thomas E. & Billups. K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686–693 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelejero C., Grimalt J. O., Sarnthein M., Wang L. & Flores J. A. Molecular biomarker record of sea surface temperature and climatic change in the South China Sea during the last 140,000 years. Mar. Geol. 156, 109–121 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Miller K. G. et al. The Phanerozoic record of global sea-level change. Science 310, 1293–1298 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. X. Sedimentary processes in the Yangtze Delta since late Pleistocene. Coll Ocean Works 7, 116–126 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J. et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz E. M., Yu Y. K., Agarwala R., Schaffer A. A., Altschul S. F. Composition-based statistics and translated nucleotide searches: improving the TBLASTN module of BLAST. BMC Boil. 4, 41 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birney E., Clamp M. & Durbin R. GeneWise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 14, 988–995 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W435–W439 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamov A. A. & Solovyev V. V. Ab initio gene finding in Drosophila genomic DNA. Genome Res. 10, 516–522 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majoros W. H., Pertea M. & Salzberg S. L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics 20, 2878–2879 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsik C. G. et al. Creating a honey bee consensus gene set. Genome Boil. 8, R13 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. & Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A. & Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence database and its supplement TrEMBL in 2000. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 45–48 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann B. et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 365–370 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zdobnov E. M. & Apweiler R. InterProScan--an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics 17, 847–848 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J. P. & Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17, 754–755 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D., Taboada G. L., Doallo R. & Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. methods 9, 772 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. Estimating the rate of molecular evolution: incorporating non-contemporaneous sequences into maximum likelihood phylogenies. Bioinformatics 16, 395–399 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Nielsen R. & Yang Z. Evaluation of an improved branch-site likelihood method for detecting positive selection at the molecular level. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 2472–2479 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R. et al. SNP detection for massively parallel whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res. 19, 1124–1132 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S9, Supplementary Tables S1-S20, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References