Abstract

Background

A herpes simplex virus (HSV) 2 candidate vaccine consisting of glycoprotein D (gD2) in alum and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) reduced genital herpes disease in HSV-1 seronegative women, but not in men or HSV-1 seropositive women.

Methods

To determine the effect of HSV-1 serostatus on effectiveness of different vaccines, we tested gD2 in alum/MPL, gD2 in Freund's adjuvant, and dl5-29 (a replication-defective HSV-2 mutant) in seropositive or seronegative guinea pigs.

Results

In HSV-1 seronegative animals, dl5-29 induced the highest titers of neutralizing antibody, and after vaginal challenge with wild-type virus, dl5-29 resulted in lower rates of vaginal shedding, lower levels of HSV DNA in ganglia, and a trend for less acute and recurrent genital herpes than the gD2 vaccines. In HSV-1 seropositive animals, all three vaccines induced similar titers of neutralizing antibodies and showed similar levels of protection against acute and recurrent genital herpes after vaginal challenge with wild-type virus, but dl5-29 reduced vaginal shedding after challenge more than the gD2 vaccines.

Conclusions

dl5-29 is an effective vaccine in both HSV-1 seropositive and seronegative guinea pigs, and was superior to gD2 vaccines in reducing virus shedding after challenge in both groups of animals which might reduce transmission of HSV-2.

Keywords: Herpes simplex virus 1, Herpes simplex virus 2, Vaccine, Replication-Defective Virus, Glycoprotein D

Introduction

Primary infection of herpes simplex virus (HSV) results in life-long latent infection. HSV-2 is usually latent in sacral ganglia where reactivation results in genital herpes. HSV-2 can cause neonatal herpes, and HSV-2 is a risk factor for acquisition of human immunodeficiency virus [1, 2].

Two trials found that HSV-2 glycoprotein D (gD2) and glycoprotein B (gB2) in MF59 adjuvant failed to protect persons from new HSV-2 infections [3]. Stanberry and colleagues [4] performed two trials using gD2 in alum and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and showed that the vaccine reduced genital herpes disease in HSV-1 seronegative women, but not HSV-1 seropositive women or in men. The difference in results in these clinical trials may have been due to differences in adjuvants or immunogens. The HSV-1 serostatus prior to vaccination may also affect the efficacy of an HSV-2 glycoprotein vaccine. Seropositivity for HSV-1 does not significantly reduce the rate of HSV-2 infection [5], but does reduce symptomatic HSV-2 infection [6]. Since seroprevalence rates of HSV-1 are >50% for healthy adults in the United States, the lack of effectiveness of an HSV-2 vaccine in HSV-1 seropositive women represents a substantial impediment.

Previously we reported that a replication-defective HSV-2 candidate vaccine, HSV-2 dl5-29, and gD2 in complete Freund's adjuvant followed by incomplete Freund's adjuvant (CFA/IFA) had similar efficacy for protection against acute and recurrent disease in guinea pigs [7]. HSV-2 dl5-29, however, induced higher levels of neutralizing antibodies in guinea pigs. Few studies have compared the effects of different vaccines and different adjuvants on the effectiveness of HSV-2 vaccines in animals, and none have tested HSV-2 vaccines in HSV-1 seropositive animals. We used a guinea pig model of genital HSV-2 to evaluate the ability of vaccines to induce immunity and protect against acute and recurrent HSV-2 disease. In one series of experiments we compared HSV-2 dl5-29 with recombinant gD2 vaccines in two different adjuvants in HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs, and in another set of experiments we compared these vaccines in HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs.

METHODS

Viruses and vaccines

Replication-defective HSV-2 dl5-29 was described previously [8, 9]. Recombinant glycoprotein D of HSV-2 (gD2) [10] was a gift from Chiron Corp (Emeryville, CA). Each animal received gD2 (3μg) mixed with CFA or IFA (50μL, Sigma-Aldrich Corp. St. Louis, MO) or absorbed to alum (75μg, Imject Alum, Pierce, Rockford, IL) by mixing on a rotating wheel for 30 min at room temperature followed addition of MPL (7.5μg, Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, AL).

Guinea pig genital herpes model

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. For HSV-1 seropositive guinea pig experiments, 4 to 6 week old female Hartley guinea pigs (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Fredrick, MD) were infected with 1 × 106 of HSV-1 (strain KOS) intranasally and 7 weeks later HSV-1 neutralizing antibody titers were measured. HSV-1 seropositive animals were immunized with PBS or gD2 i.m. in the thigh or with 1×106 pfu of HSV-2 dl5-29 s.c. on the back. Each vaccine was given on days 49 and 28 before intravaginal challenge with 1 × 106 or 4 × 106 of HSV-2 strain 333. A higher challenge dose of HSV-2 strain 333 was required in HSV-1 seropositive animals to induce genital herpes disease than for HSV-1 seronegative animals (unpublished data) as was expected since HSV-1 has been shown to reduce symptomatic HSV-2 infection [6]. In preliminary experiments, HSV-1 seropositive animals did not develop genital herpes disease after challenge with the same dose of wild-type virus (2 × 105 pfu) that routinely causes disease in HSV-1 seronegative animals. We empirically found that increasing the dose of the challenge inoculum by 5-20 fold resulted in genital disease in most HSV-1 seronegative animals after challenge with wild-type HSV-2. For HSV-1 seronegative animal experiments, 4 to 6 week old female Hartley guinea pigs were vaccinated with same vaccines described above and challenged intravaginally with 2 × 105 HSV-2 stain 333. Animals that died early after challenge were included in the analysis until their death and then were omitted from further analysis. Lesion severity after challenge was determined by direct examination of each animal daily for up to 60 days based on a scale of 0 for no lesions, 1 for erythema, 2 for single or a few small vesicles, 3 for large or fused vesicles, and 4 for ulcerated lesions [7]. Animals were sacrificed after the last day of scoring and lumbosacral ganglia were stored at −20°C.

Neutralizing antibody responses, titration of virus shedding, and real-time PCR

Neutralizing antibody titers to HSV-2 strain 333 or HSV-1 strain KOS were quantified as described previously [7]. Vaginal fluid was collected after challenge, and HSV-2 titers were determined as previously described [7]. Animals that were negative for shedding after challenge (1-3 animals from each group) were considered inadequately challenged and excluded from further analysis; these animals showed no change in HSV antibody titers after challenge (data not shown).

DNA from lumbosacral ganglia of individual latently infected guinea pigs was isolated using a 5Prime, ArchivePure DNA isolation kit (Fischer Scientific Company, LLC, Pittsburgh, PA). Latent HSV-2 DNA was quantified by real-time PCR using a Taqman System, 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with primers and probes specific for HSV gD (which detect both HSV1 and HSV2 gD) [7] or HSV-1 gG [11]. For statistical purposes, reactions yielding less than 4 copies of HSV-2 DNA (the lower limit of detection of the assay) were assumed to contain 2 copies. The mean result for three independent experiments was determined.

Luciferase Immunoprecipitation-assay System (LIPS)

A LIPS assay [12] for quantifying antibody titers was described previously [13]. Briefly, Renilla luciferase-HSV-2 gB2, gD2, and ICP8 fusion proteins were harvested from transfected cell lysates and activity of lysates (light units (LU)/ ml) was determined by luminometry. Antibody titers were measured in LIPS assays by adding guinea pig serum to 1 × 107 light units (LU) of cell extract, immunoprecipitation was performed with addition of protein A/G beads, and LU were determined by luminometry. Background LU values were determined by sera from 3 uninfected guinea pigs. A cut-off threshold limit was derived from the mean value plus 3 standard deviations of background LU for each HSV-2 antigen. All LU data shown represent the average of two independent experiments after the cut-off threshold values have been subtracted out.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was done using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple comparisons with Student t-test, unless otherwise described.

RESULTS

HSV-2 dl5-29 induces significantly higher neutralizing antibodies compared with gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2 (alum/MPL) in guinea pigs despite lower gD2-specific antibody responses

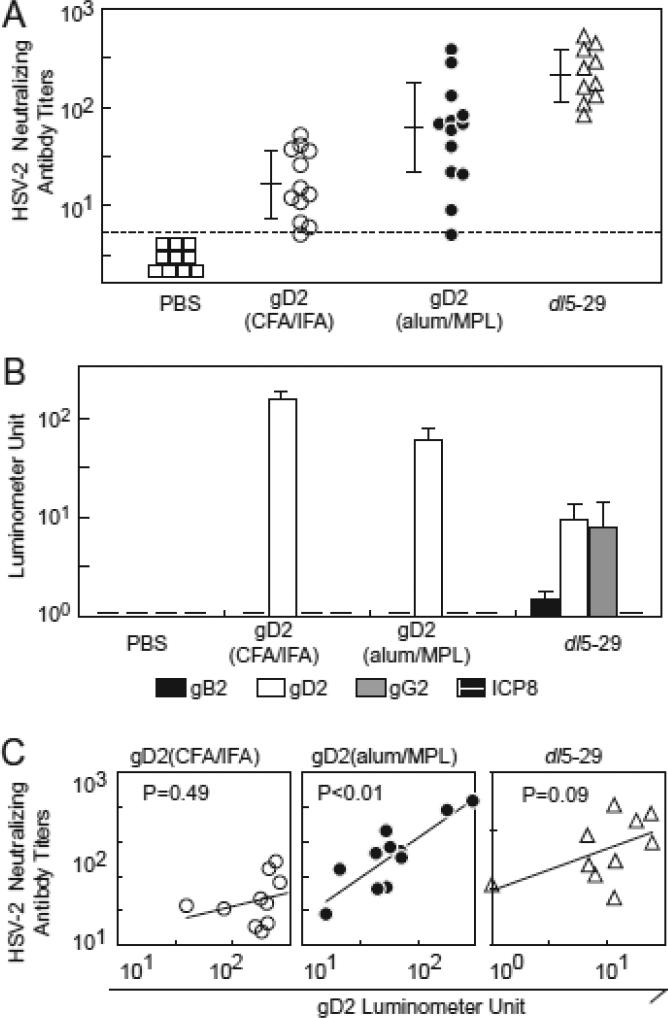

Serum neutralizing titers of HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs receiving dl5-29 were significantly higher than those receiving gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2(alum/MPL) (p<0.01, Fig. 1A). Neutralizing titers in animal receiving gD2 (alum/MPL) were significantly higher than those receiving gD2(CFA/IFA) (p<0.01). These results confirm our previous finding that dl5-29 induces higher neutralizing antibody titers than gD2(CFA/IFA) in guinea pigs.

Figure. 1.

Neutralizing and HSV-2 antigen-specific antibody titers induced by vaccines in guinea pigs. (A) Neutralizing antibody titers (50% plaque reduction) of sera from HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs were determined three weeks after the second vaccination. Each symbol represents an individual animal, short horizontal bars represent mean ± standard deviation for each group, vertical lines represent standard errors, and broken line indicates the limit of detection. Antibody titers were determined in 10, 12, 13, and 10 animals that received PBS (control), gD2(CFA/IFA), gD2(alum/MPL), and dl5-29, respectively. (B) Anti-gB2, gD2, gG2 and HSV-2 ICP8 antibody titers induced by the different vaccines (x axis) before challenge were assayed using the LIPS assay and antibody titers are shown in light units on the y axis. Short horizontal bars on the x-axis indicate that no animal in the group showed a detectable antibody response. All titers shown have background activity (mean plus 3 times the standard deviation of negative control serum) subtracted from the data shown. (C) Correlation between anti-gD2 antibody titers induced by gD2 and dl5-29 vaccines (x axis) and neutralizing antibody titers (y axis). Lines in panels C indicate linear regression lines.

Vaccination with dl5-29 induced anti-gB2, -gD2 and -gG2 antibodies, but not anti-ICP8 which is deleted in dl5-29 (Fig. 1B). Anti-gD2 titers were significantly higher in animal receiving gD2(CFA/IFA) than gD2(alum/MPL) (p<0.01), although HSV-2 neutralizing antibody titers were significantly higher with gD2(alum/MPL) than gD2(CFA/IFA) (p<0.01) (Fig. 1A). Anti-gD2 titers in animals receiving dl5-29 were significantly lower than those receiving gD2(alum/MPL) or gD2(CFA/IFA) (p<0.01). HSV-2 neutralizing antibody titers showed a significant correlation with gD2-specific antibody titers in animal receiving gD2(alum/MPL) (p<0.01), but not gD2(CFA/IFA) (p=0.49) dl5-29 (p=0.09) (Fig 1C). No correlation was seen for HSV-2 neutralizing antibody titers with gB2 antibody in animals receiving dl5-29 (data not shown). These data indicate that titers of gD2 antibody do not necessarily correlate with neutralizing antibody titers, and that the contribution of individual viral proteins to the neutralizing antibody is dependent on context of the vaccine and the adjuvant used.

HSV-2 dl5-29 reduces vaginal shedding in guinea pigs more effectively than gD2(alum/MPL) or gD2(CFA/IFA) after challenge with wild-type HSV-2

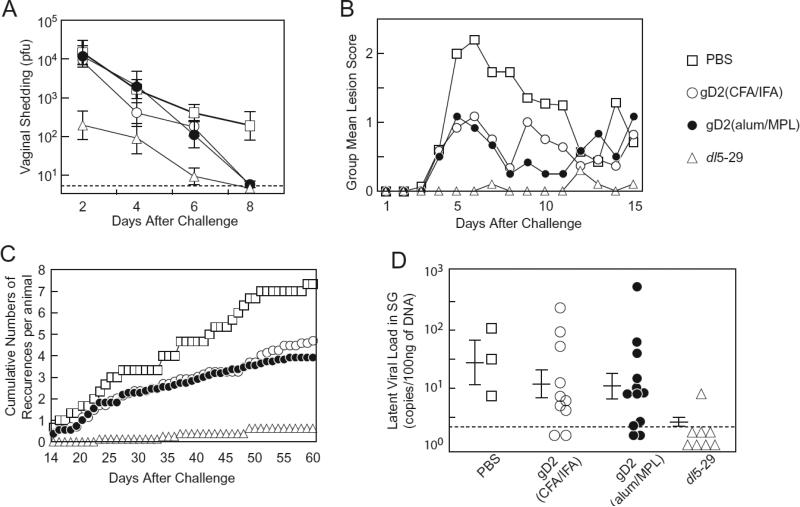

After challenge with wild-type HSV-2, titers of HSV-2 shed from the vaginal tract were consistently and significantly lower (p<0.01) in animals vaccinated with dl5-29 than with gD2(alum/MPL) at all time points except day 8, and lower than gD2(CFA/IFA) on days 2 and 6 (Figure 2A). HSV-2 titers were significantly lower for dl5-29 vs. PBS at all time points (p<0.01). HSV-2 titers in animals receiving gD2(alum/MPL) and gD2(CFA/IFA) were similar. Thus, dl5-29 was the most effective vaccine to reduce HSV-2 vaginal shedding after challenge, while gD2(alum/MPL) and gD2(CFA/IFA) each had a modest effect.

Figure 2.

Vaccination of HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs with dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), gD2(alum/MPL), or PBS. Animals were vaccinated twice with either PBS (control), gD2(CFA/IFA), gD2(alum/MPL), or dl5-29 separated by a 3 week interval, and challenged with wild-type HSV-2 intravaginally at 3 weeks after the second vaccination. (A) HSV-2 shedding from the vaginal tract on days 2, 4, 6 and 8 after challenge with wild-type HSV-2. Titers of HSV-2 were not different for PBS vs. gD2(alum/MPL) or vs. gD2(CFA/IFA) on days 2, 4 and 6 (p>0.15), and not different for gD2(alum/MPL) vs. gD2(CFA/IFA) at any time point (p>0.15). The number of animals vaccinated that shed virus after challenge was 13, 12, 12, 8 for PBS (control), gD2(CFA/IFA), gD2(alum/MPL), or dl5-29, respectively. Five animals did not become infected after challenge (2 received PBS, 1 received gD2(alum/MPL), 2 received dl5-29). (B) Acute disease scores for the 3 vaccinated groups were significantly lower than that of the PBS group (p=0.035, 0.044, and <0.01 for gD2(CFA/IFA), gD2(alum/MPL), and dl5-29 vs.PBS, respectively). Differences between dl5-29 and gD2(alum/MPL) or gD2(CFA/IFA), or between gD2(alum/MPL) and gD(CFA/IFA) were not significant (p≥0.08). (C) Cumulative number of recurrences in animals vaccinated with dl5-29 or gD2(alum/MPL) were significantly lower than those receiving PBS (p<0.01 for dl5-29 vs. PBS, p =0.035 for gD2(alum/MPL) vs. PBS); recurrences for animals vaccinated with gD2(CFA/IFA) was not significantly lower than those receiving PBS (p=0.09). (D) Latent HSV-2 load in pooled sacral ganglia (SG) after challenge with wild-type virus. Each symbol indicates individual animals from the same group. Horizontal bars indicate mean ± SE, vertical bars indicate standard errors, and the broken line indicates the limit of detection. The number of animals surviving and analyzed for latent viral DNA was 3, 10, 12, 8 for PBS (control), gD2(CFA/IFA), gD2(alum/MPL), or dl5-29, respectively.

Acute disease scores and numbers of recurrences after wild-type HSV-2 challenge in guinea pigs vaccinated with HSV-2 dl5-29, gD2(alum/MPL), or gD2(CFA/IFA)

Animals vaccinated with dl5-29 had minimal disease scores during the first two weeks after challenge, while those vaccinated with gD2(alum/MPL) or gD2(CFA/IFA) had lower disease scores than those receiving PBS, but higher than those vaccinated with dl5-29 (Figure 2B). The acute disease scores for the vaccinated groups (p<0.01, p=0.04, and p=0.04 for dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), and gD2(alum/MPL), respectively) were significantly lower than that of the PBS group, but were not significantly different from each other. Animals vaccinated with dl5-29 had fewer numbers of recurrences than those receiving gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2(alum/MPL) (Figure 2C). The differences between the dl5-29 and gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2(alum/MPL) groups were not significant.

The latent viral load of guinea pigs vaccinated with HSV-2 dl5-29 is significantly lower than those vaccinated with gD2(alum/MPL) or gD2(CFA/IFA) after challenge with HSV-2

The latent viral load of HSV-2 in sacral ganglia of animals vaccinated with dl5-29 was significantly lower than that of other groups (p<0.03) (Figure 2D). The latent viral loads were not significantly different among PBS, gD2(CFA/IFA) and gD2(alum/MPL) groups. In the present experiment 77% of animals in the PBS control group died after HSV-2 challenge, while in prior experiments [7] 23% died (p<0.01, PBS vs. any vaccine group, data not shown). While the dose of challenge virus was the same in both experiments, animals were from a different supplier and had lower body weights in the present experiment. Since only 3 animals survived in the PBS group, the statistical power for comparison between this group and the other groups was low.

Antibody responses against HSV-2 gB, gD, gG, and ICP8 were detected in all vaccine groups after challenge using the LIPS assay (data not shown). Anti-gD2 antibody titers were increased in all vaccine groups including gD2 vaccine recipients after challenge. Antibody titers to gB2, gG2, and ICP8 (absent in the dl5-29) were also increased in dl5-29 group after challenge, even though these animals showed minimal acute and recurrent disease. Antibody to ICP8 was detected in some animals that received dl5-29 (which is deleted for this protein) after challenge; however, the titer of ICP8 antibody was low in animals receiving dl5-29, which mirrored the mild acute and recurrent disease in these animals after challenge.

Analysis of antibody titers after vaccination, but before challenge, showed that the level of HSV-2 neutralizing titers or gD2 titers did not correlate with severity of acute disease, shedding, numbers of recurrences, or latent viral loads in animals receiving the gD2 vaccines (data not shown), suggesting that neutralizing antibody alone is insufficient for protection from HSV-2 genital disease.

Neutralizing titers against HSV-2 are similar in HSV-1 seropositive animals vaccinated with HSV-2 dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), and gD2(alum/MPL)

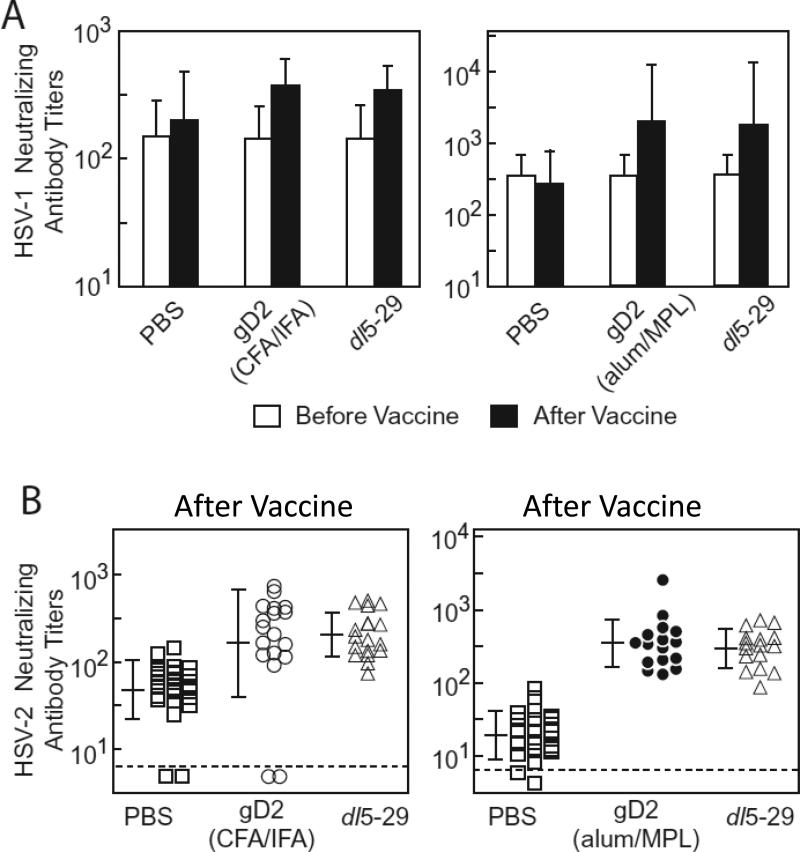

Guinea pigs were infected with HSV-1, virus neutralizing antibody titers were determined in each animal, and the animals were divided into 3 groups so that levels of HSV-1 neutralizing antibody titers would be similar for subsequent vaccine studies (Figure 3A). HSV-1 neutralizing antibody titers were significantly increased after vaccination with gD2(CFA/IFA), gD2(alum/MPL), or dl5-29 compared to the titers before vaccination (p<0.01 for each group before vs. after vaccination) (Figure 3A). HSV-1 neutralizing antibody titers in the PBS group were similar before and after vaccination. HSV-1 neutralizing titers in animals vaccinated with each of the three vaccines were significantly higher than those that received PBS (p<0.02), while the HSV-1 neutralizing titers were not significantly different between the vaccinated groups. (Figure 3A). Therefore, the three vaccines boosted anti-HSV-1 neutralizing antibody titers to similar levels.

Figure 3.

HSV-1 and HSV-2 neutralizing antibody titers in HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), and gD2(alum/MPL). (A) Guinea pigs previously infected with HSV-1 were vaccinated with either PBS (control), gD2(CFA/IFA), or dl5-29 (left panel) or PBS, gD2(alum/MPL), or dl5-29 (right panel). Neutralizing antibody titers against HSV-1 before (open bars) and after (solid bars) two doses of vaccine are shown. Open and solid bars indicate geometric mean titer in each group and vertical lines indicate standard deviations. (B) HSV-2 neutralizing antibody titers were determined in animals vaccinated with PBS, gD2(CFA/IFA), or dl5-29 (left panel), and PBS, gD2(alum/MPL) or dl5-29 (right panel). Individual symbols indicate the titer for each animal, horizontal bars indicate mean titers, vertical lines show standard deviations, and broken lines indicates the limit of detection. The number of animals infected with HSV-1 and vaccinated was 27, 18, 18, for PBS (control), gD2(CFA/IFA), or dl5-29, respectively, left panels in A and B, and 23, 16, 16, for PBS (control), gD2(alum/MPL), or dl5-29, respectively, right panels in A and B.

HSV-2 neutralizing antibody titers in animals vaccinated with dl5-29 vs. gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2(alum/MPL) were not significantly different (Figure 3B). HSV-2 neutralizing titers in HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs of PBS group were significantly lower than those of dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), or gD2(alum/MPL) (p<0.01).

HSV-2 dl5-29 reduces vaginal shedding after challenge in HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs more effectively than gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2(MPL/alum)

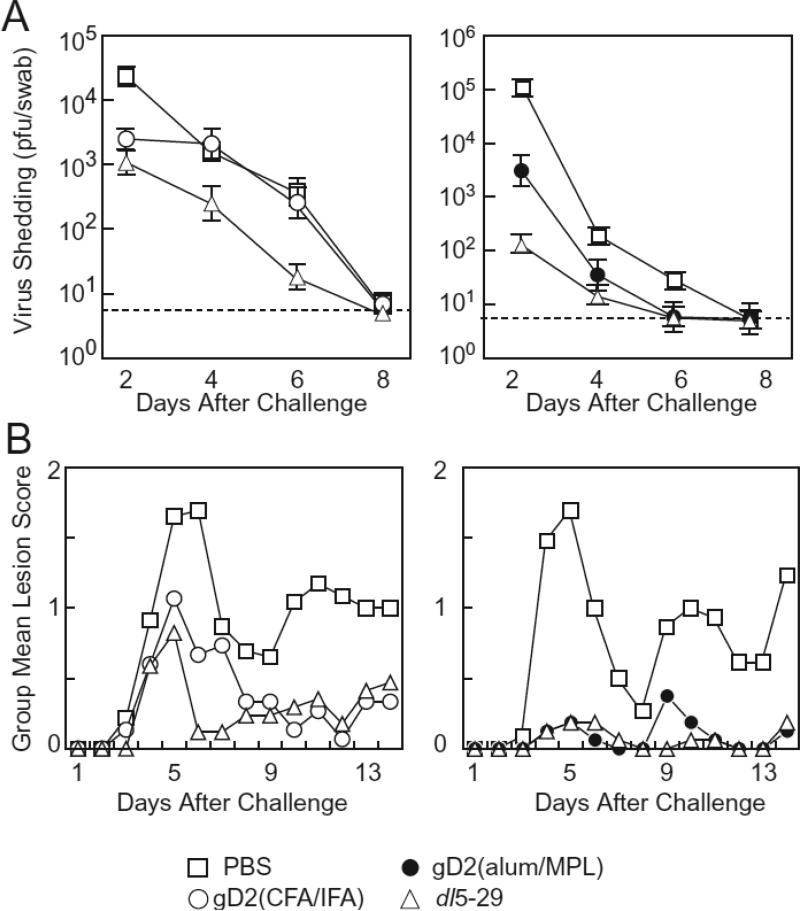

HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs were vaccinated twice and then challenged with wild-type HSV-2 intravaginally (1×106 or 4×106 pfu for left and right panel, respectively, Figure 4A). Titers of HSV-2 shed from animals vaccinated with dl5-29 or gD2(alum/MPL) were significantly lower than those that received PBS on day 2, 4 and 6 (p<0.01), but not day 8 after challenge. Titers of HSV-2 of gD2(CFA/IFA) group were significantly lower than that of PBS only on day 2 (p<0.01), but not on day 4, 6 or 8. The differences in HSV-2 shedding between animals vaccinated with dl5-29 and gD2(alum/MPL) were significant on day 2 (p<0.01), but not day 4, 6 or 8. Titers of HSV-2 shed from animals receiving dl5-29 were significantly lower than those of gD2(CFA/IFA) on day 4 and 6 (p<0.01), but not days 2 and 8. Therefore, animals vaccinated with dl5-29 had the lowest levels of HSV-2 shedding after challenge, while those vaccinated with gD2(alum/MPL) had the next lowest levels.

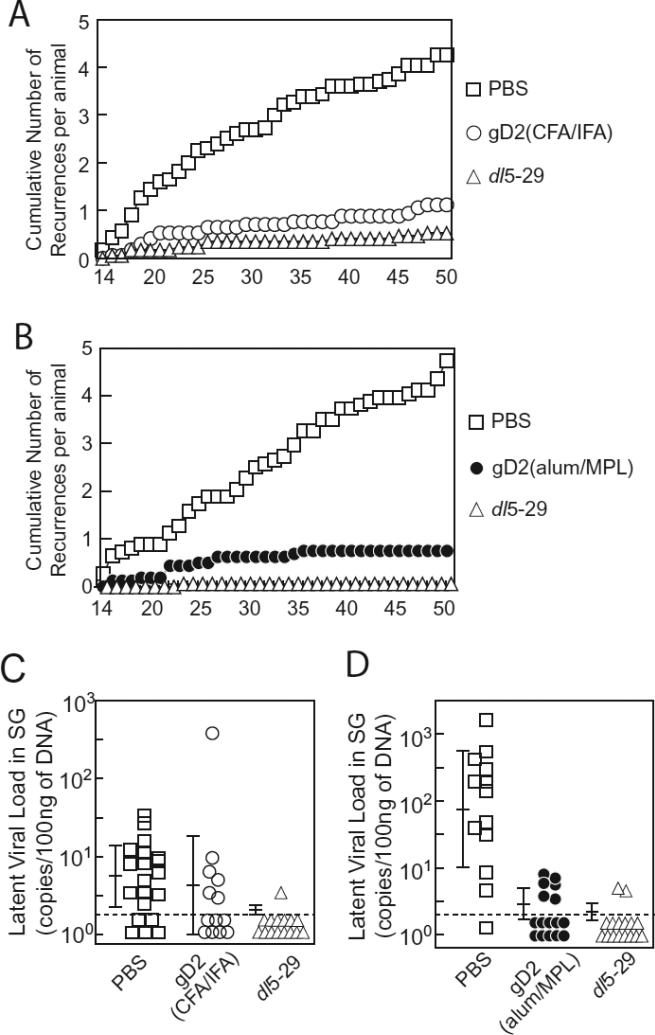

Figure 4.

Shedding of HSV-2 and acute disease scores in HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), and gD2(alum/MPL). (A) Geometric mean titers of HSV-2 shed from the vaginal tract on day 2, 4, 6 and 8 of animals vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), or PBS (left panel), and animals vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(alum/MPL), or PBS (right panel). Vertical bars indicate standard errors and broken lines indicate the limit of detection. (B) Group mean lesion scores for acute infection in animals vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), or PBS (left panel), and animals vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(alum/MPL), or PBS (right panel). The number of animals analyzed for shedding and acute disease was 26, 18, 18, for PBS (control), gD2(CFA/IFA), or dl5-29, respectively (left panels in A and B), and 23, 16, 16, for PBS (control), gD2(alum/MPL), or dl5-29, respectively (right panels in A and B). One animal (in the PBS group in the left panels) did not become infected after challenge.

HSV-2 dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), and gD2(alum/MPL) protect HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs from acute and recurrent disease after challenge

Acute disease scores of HSV-1 seropositive animals were significantly lower in dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA) and gD2(alum/MPL) groups than in PBS group (p<0.01), while the difference between dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), or gD2(alum/MPL) were not significant (Figure 4B). The mean number of cumulative recurrences was significantly lower for animals vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), or gD2(alum/MPL) than for those vaccinated with PBS (p<0.01). Animals vaccinated dl5-29 had fewer recurrences than those receiving gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2(alum/MPL), but the differences were not significant (Figure 4A, B), due to the low reactivation rates in the gD2 recipients.

HSV-2 dl5-29 and gD2(alum/MPL) significantly reduce the HSV latent viral load in HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs

The latent viral loads in animals vaccinated with dl5-29 were significantly lower than those receiving PBS (p<0.01) (Figure 5C, D). The latent viral loads in the gD2(CFA/IFA) and PBS groups were similar, but the difference between gD2(CFA/IFA) and dl5-29 was significant (p=0.043) (Figure 5C). The latent viral load in animals receiving gD2(alum/MPL) was significantly lower than that of PBS (p<0.01) (Figure 6D), while the latent viral load of the dl5-29 and gD2(alum/MPL) groups were similar. Animals were challenged with 4-fold higher titers of wild-type HSV-2 in the experiment with gD2(alum/MPL) than animals in the experiment with gD2(CFA/IFA), which is reflected in the higher latent viral load in the PBS group in Figure 5D than that of PBS group in Figure 5C. Therefore, the low latent viral loads of dl5-29 and gD2(alum/MPL) suggest that these vaccines were especially effective in reducing the viral load.

Figure 5.

Cumulative number of recurrences and latent viral loads in HSV-1 seropositive animals vaccinated with dl5-29, gD2(CFA/IFA), and gD2(alum/MPL). Cumulative numbers of recurrences in animals vaccinated with PBS (n=26), gD2(CFA/IFA) (n=18), or dl5-29 (n=18) (A), and animals vaccinated with PBS (n=23), gD2(alum/MPL) (n=16), or dl5-29 (n=16) (B). Latent HSV-2 loads in sacral ganglia (SG) in animals were analyzed in animals vaccinated with PBS (n=20), gD2(CFA/IFA) (n=13), or dl5-29 (n=15) (C), and animals vaccinated with PBS (n=13), gD2(alum/MPL) (n=16), or dl5-29 (n=16) (D). Each symbol indicates individual animals from the same group. Horizontal bars indicate mean ± standard deviation, and the broken line indicates the limit of detection.

Discussion

We have shown that in HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs dl5-29 induces higher titers of HSV-2 neutralizing antibodies than gD2(alum/MPL) or gD2(CFA/IFA), and that dl5-29 results in lower rates of virus shedding, lower latent viral loads in ganglia, and a tendency for less acute and recurrent genital herpes disease compared with gD2(alum/MPL) or gD2(CFA/IFA) after challenge with wild-type virus. In HSV-1 seropositive guinea pigs, all three vaccines showed similar titers of HSV-2 neutralizing antibody and equivalent protection against acute and recurrent HSV-2 disease after challenge; however, dl5-29 resulted in the lowest virus shedding, and dl5-29 and gD2(alum/MPL) significantly reduced the latent viral load. Detection of antibody to HSV ICP8, albeit at low titers in animals that received dl5-29, suggests that this antibody might be useful as a marker of infection if such a vaccine was used in humans. We have previously shown that antibody to ICP-8 can readily be detected in HSV-2 seropositive humans [13].

To date, all animal studies of genital herpes vaccines have been done in HSV-1 seronegative animals. We found that gD2 in alum/MPL (as well as gD2(CFA/IFA) and dl5-29) was effective in protecting HSV-1 seropositive female guinea pigs, indicating that the animal model did not recapitulate the lack of efficacy of gD2 in alum/MPL observed in HSV-1 seropositive women. Several features of the model might explain the differences in the animal and human studies. First, guinea pigs were vaccinated 2 to 3 months after HSV-1 infection, while in the clinical trial the interval between HSV-1 infection and vaccination was many years. Immune responses are known to mature after infection with an increasing avidity [14] and the long period between HSV-1 infection and vaccination in the clinical trial may have favored better protection to HSV-2. Second, the interval between vaccination and HSV-2 infection was shorter in the animal experiments than in the clinical trial. In a clinical trial of gD2 and gB2 in MF59 adjuvant, while the vaccine was not effective during the one-year follow-up period, there was a lower rate of genital herpes during the first 5 months after vaccination [3]. Third, the challenge dose of wild-type virus might be higher in animal experiments where nearly all the animals are infected by the challenge dose, than after natural infection of humans. Cross-protection against HSV-2 in HSV-1 seropositive animals might be insufficient to protect animals from a high titer HSV-2 challenge, while it might protect humans from a low titer virus challenge and mask the efficacy of a HSV-2 vaccine.

We also compared gD2 in two different adjuvants, CFA/IFA and alum/MPL, for their ability to protect HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs. Rupp et al [15] reviewed human trials of gD2 vaccines and noted that gD2 and gB2 in MP59 adjuvant [3] induced higher levels of neutralizing antibody, while gD2 in alum/MPL [4] induced higher Th-1 cell-mediated immune responses. Bourne and colleagues [16] compared guinea pigs vaccinated with gD2 in alum versus gD2 in alum/MPL and found that the both provided similar protection against acute disease after intravaginal challenge with HSV-2, but that gD2 in alum/MPL provided better protection against recurrent disease than gD2 in alum. Berman et al [17] vaccinated guinea pigs with gD1 in CFA or alum and challenged the animals with HSV-2 by intravaginal infection; animals receiving gD2 in CFA were protected from acute genital disease, while those receiving gD2 in alum were only partially protected. Sanchez-Pescador and colleagues [18] compared guinea pigs immunized with gD1 in CFA and alum, and found that gD1 in CFA resulted in lower acute disease scores than gD1 in alum after intravaginal challenge with HSV-2. We performed the first comparison of gD2 in alum/MPL versus gD2 in CFA and found that gD2(alum/MPL) was as effective as gD2(CFA/IFA) in protecting HSV-1 seronegative or seropositive guinea pigs from acute and recurrent HSV-2.

We found that dl5-29 significantly reduced the latent viral load compared with gD2(CFA/IFA) or gD2(alum/MPL) in HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs after challenge with HSV-2 and that dl5-29 vaccinated animals had a reduced acute and recurrent genital herpes disease (but this did not reach statistical significance). In our prior experiments [7] there was no significant different in the latent viral load in HSV-1 seronegative guinea pigs receiving dl5-29 and gD2 in CFA/IFA, and the different in acute and recurrent genital herpes disease was less apparent in the two vaccines. While the dose of challenge virus was the same, in the current experiment more animals died in control group. Thus dl5-29 may be more effective than the gD2 vaccines at effectively higher challenge inocula.

We found that neutralizing antibody titers prior to challenge did not correlate with reduced severity of acute or recurrent disease in animals that received the gD2 vaccines, indicating that other factors besides, or in addition to, neutralizing antibodies are important for protection for HSV-2 disease. While both antibody and cellular immunity are important, the true immunologic correlates of protection from HSV-2 genital disease are not known [19]; therefore animal studies continue to be important for testing vaccines. In human trials, the gender and HSV-1 serostatus of vaccine recipients have been important determinants for vaccine efficacy. Since 50% or more of adults are HSV-1 seropositive and the immune response to HSV-1 affords some level of cross-protection from HSV-2 disease, future studies of HSV-2 vaccines need to be performed in HSV-1 seropositive animals. Our experiments have shown that dl5-29 is an effective candidate vaccine in both HSV-1 seronegative and seropositive guinea pigs, and that dl5-29 reduces vaginal shedding significantly better than gD2 vaccines in both HSV-1 seronegative and seropositive guinea pigs. Mathematical modeling suggests that reduced shedding of HSV-2 by vaccination may have a substantial impact at the population level by limiting transmission of genital herpes [20]. Thus, these studies indicate that dl5-29 represents an excellent candidate HSV-2 vaccine for clinical trials in humans.

Acknowledgements

We thank Caleb Canders and Juan Lacayo for scoring guinea pigs, and Samuel Myerowitze-Vanderhoek and Akiko Ohira for measuring neutralizing antibody titers. This study was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and NIH grant AI057552 to DMK.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: D.M.K. is an inventor on a patent that has been licensed from Harvard by Sanofi Pasteur involving one of the vaccines, and is a consultant for Sanofi Pasteur. The other authors do not have a conflict of interest.

We have indicated funding sources in the acknowledgements.

Part of this work was presented at the American Society for Virology 27th Annual Meeting, Ithaca, NY, July 2008

References

- 1.Freeman EE, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Cross PL, Whitworth JA, Hayes RJ. Herpes simplex virus 2 infection increases HIV acquisition in men and women: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. AIDS. 2006;20:73–83. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198081.09337.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schacker T, Ryncarz AJ, Goddard J, Diem K, Shaughnessy M, Corey L. Frequent recovery of HIV-1 from genital herpes simplex virus lesions in HIV-1-infected men. JAMA. 1998;280:61–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corey L, Langenberg AG, Ashley R, et al. Recombinant glycoprotein vaccine for the prevention of genital HSV-2 infection: two randomized controlled trials. Chiron HSV Vaccine Study Group. JAMA. 1999;282:331–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stanberry LR, Spruance SL, Cunningham AL, et al. Glycoprotein-D-adjuvant vaccine to prevent genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1652–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Looker KJ, Garnett GP. A systematic review of the epidemiology and interaction of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:103–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.012039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langenberg AG, Corey L, Ashley RL, Leong WP, Straus SE. A prospective study of new infections with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. Chiron HSV Vaccine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1432–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911043411904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino Y, Dalai SK, Wang K, et al. Comparative efficacy and immunogenicity of replication-defective, recombinant glycoprotein, and DNA vaccines for herpes simplex virus 2 infections in mice and guinea pigs. J Virol. 2005;79:410–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.410-418.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Costa X, Kramer MF, Zhu J, Brockman MA, Knipe DM. Construction, phenotypic analysis, and immunogenicity of a UL5/UL29 double deletion mutant of herpes simplex virus 2. J Virol. 2000;74:7963–71. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.7963-7971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Da Costa XJ, Jones CA, Knipe DM. Immunization against genital herpes with a vaccine virus that has defects in productive and latent infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6994–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanberry LR, Bernstein DI, Burke RL, Pachl C, Myers MG. Vaccination with recombinant herpes simplex virus glycoproteins: protection against initial and recurrent genital herpes. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:914–20. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pevenstein SR, Williams RK, McChesney D, Mont EK, Smialek JE, Straus SE. Quantitation of latent varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus genomes in human trigeminal ganglia. J Virol. 1999;73:10514–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10514-10518.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramanathan R, Burbelo PD, Groot S, Iadarola MJ, Neva FA, Nutman TB. A luciferase immunoprecipitation systems assay enhances the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:444–51. doi: 10.1086/589718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burbelo PD, Hoshino Y, Leahy H, et al. Serological diagnosis of human HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection by luciferase immunoprecipitation systems (LIPS) assay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:366–71. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00350-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow RA, Friedrich D, Krantz E, Wald A. Development and use of a type-specific antibody avidity test based on herpes simplex virus type 2 glycoprotein G. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:508–15. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000135993.06508.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rupp R, Rosenthal SL, Stanberry LR. Pediatrics and herpes simplex virus vaccines. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;16:31–7. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourne N, Bravo FJ, Francotte M, et al. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2 glycoprotein D subunit vaccines and protection against genital HSV-1 or HSV-2 disease in guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:542–9. doi: 10.1086/374002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman PW, Gregory T, Crase D, Lasky LA. Protection from genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection by vaccination with cloned type 1 glycoprotein D. Science. 1985;227:1490–2. doi: 10.1126/science.2983428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanchez-Pescador L, Burke RL, Ott G, Van Nest G. The effect of adjuvants on the efficacy of a recombinant herpes simplex virus glycoprotein vaccine. J Immunol. 1988;141:1720–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koelle DM, Corey L. Recent progress in herpes simplex virus immunobiology and vaccine research. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:96–113. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.96-113.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garnett GP, Dubin G, Slaoui M, Darcis T. The potential epidemiological impact of a genital herpes vaccine for women. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:24–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2002.003848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]