Abstract

How tissue damage is detected to induce inflammatory responses is unclear. Most studies have focused on damage signals released by cell breakage and necrosis1. Whether tissues utilize other cues besides cell lysis to detect that they are damaged is unknown. We find that osmolarity differences between interstitial fluid and the external environment mediate rapid leukocyte recruitment to sites of tissue damage in zebrafish by activating cytosolic phospholipase a2 (cPLA2) at injury sites. cPLA2 initiates the production of non-canonical arachidonate metabolites that mediate leukocyte chemotaxis via a 5-oxo-ETE receptor (OXE-R). Thus, tissues can detect damage through direct surveillance of barrier integrity. By this mechanism, cell-swelling likely functions as a pro-inflammatory intermediate.

Epithelial tissue injury is associated with cell damage, disruption of cell-cell interactions, and direct exposure of cells inside the tissue to the outside environment. Leukocytes detect and migrate towards epithelial breaches over distances of several hundred micrometers within minutes. Leakage of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) from broken cells leads to leukocyte necrotaxis and is currently the best characterized paradigm for tissue damage detection1. By contrast, detection mechanisms that provide surveillance at the tissue barrier level remain poorly studied. For skin injuries, collapse of the trans-epithelial electrostatic potential has been proposed to produce an instructive, electrotactic signal2, but how this could steer leukocytes to the site of injury is unclear. Epithelia can maintain large concentration differences between the extracellular space of tissues and the external environment. The skin of freshwater organisms, such as zebrafish, as well as the mucosal surfaces of the oral cavity, esophagus, and potentially the lung3, 4 of land-mammals are exposed to hypotonicity. These epithelial barriers separate interstitial fluid that contains ions and metabolites in the high mOsm range (∼270-300 mOsm, i.e. the common extracellular tonicity of vertebrates) from the external environment that contains ions in the low mOsm range (freshwater: ∼10 mOsm, saliva: ∼ 30 mOsm). This leads to significant differences in chemical potential of specific ions and osmotic pressure across the epithelium, and disruption of these gradients could potentially be sensed by cells at the injury site.

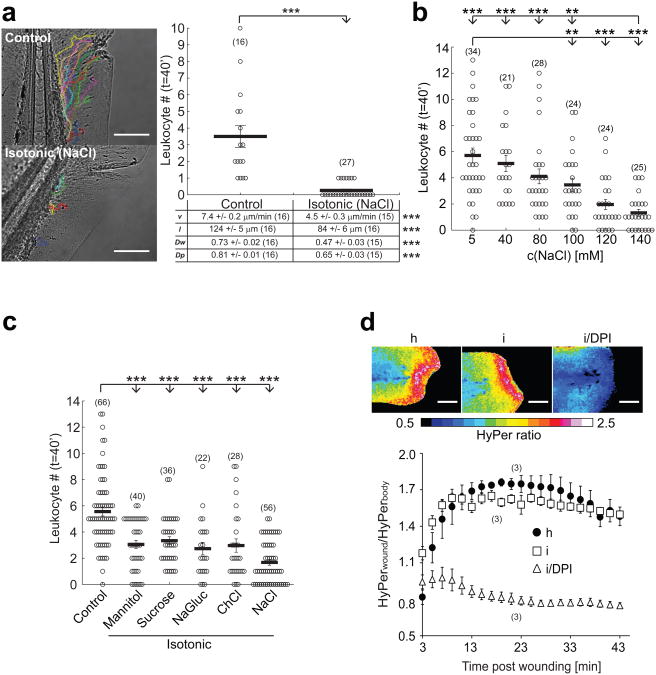

The immune system of zebrafish closely resembles that of mammals5-8. The optical transparency of their larvae allows non-invasive imaging and interrogation of tissue damage detection mechanisms by live microscopy in the intact animal. Zebrafish tail fin wounds are initially (i.e. within 40-60′ after injury) detected by neutrophils and macrophages9, 10. Migration of these myeloid leukocytes to wounds can be monitored by light transmission microscopy. To test if changes in ion concentrations or osmotic pressure are detected by leukocytes following epithelial barrier injury, we generated tail fin wounds in zebrafish larvae incubated either in hypotonic medium (resembling freshwater), or medium adjusted to the ionic composition and tonicity characteristic of vertebrate interstitial fluid by addition of NaCl. We observed a concentration-dependent (Fig. 1a, b; Supplementary Movie 1), and reversible (Supplementary Fig. S1a, b, Supplementary Movie 2) inhibition of leukocyte recruitment to the wound site, associated with decreased migration velocity and path-length (Fig. 1a, table), without obvious signs of impaired animal health under these conditions. To test if leukocyte migration inhibition was caused by increased external medium tonicity or by ion-specific effects, we replaced Cl− and Na+ ions with choline or gluconate, respectively, and used sucrose and mannose as non-ionic osmolytes. Whereas isotonic NaCl exerted the most pronounced anti-inflammatory effect, all conditions that reduced the osmolarity difference between tissue and external medium inhibited recruitment (Fig. 1c). This indicates that exposure of the zebrafish tail fin to low tonicity is required to trigger rapid recruitment of leukocytes after wounding.

Fig. 1.

Hypotonicity is required for rapid leukocyte recruitment to larval zebrafish tail fin wounds. (a) Recruitment of leukocytes to incisional tail fin wounds imaged in zebrafish larvae by light transmission microscopy. During wounding and subsequent imaging, larvae were kept either in normal, hypotonic E3 embryo medium (‘Control’, containing 5 mM NaCl) or in embryo medium that had been adjusted to the common extracellular tonicity of vertebrates (∼270-300 mOsm) by addition of 140 mM NaCl (‘Isotonic (NaCl)’, 145 mM NaCl). Left panel, representative leukocyte tracks capturing all visible cell movements within 40 min after injury. Graph: mean number of leukocytes reaching the wound within t = 40 min after injury. Table: quantification of mean velocity (v), pathlength (l), wound directionality (Dw), and path persistence (Dp). (b) Mean leukocyte recruitment to larval tail fin wounds within 40 min after injury plotted vs. salt concentration of the medium. (c) Mean leukocyte recruitment within 40 min after injury as a function of different isotonic medium compositions. ‘Control’, 5 mM NaCl. ‘Mannitol’, control + 270 mM Mannitol. ‘Sucrose’, control + 270 mM Sucrose. ‘NaGluc’, control + 135 mM sodium gluconate. ‘ChCl’, control + 135 mM choline chloride. ‘NaCl’, control + 135 mM NaCl. (d) HyPer imaging of wound margin H2O2 production in response to wounding in hypotonic (h), isotonic (i), or isotonic medium + 100 μM of the NADPH oxidase inhibitor diphenyl iodonium chloride (i/DPI). Upper panel, representative HyPer-ratio images. Red, high [H2O2]. Blue, low [H2O2]. Lower panel, normalized HyPer-ratio as a function of time after wounding. Number of larvae (n) used for the analyses is given in parentheses on the graphs. Error bars, SEM. **, t-test p< 0.005. ***, t-test p<0.0005. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Hypotonic exposure results in cell swelling through osmotic water influx11. Subnanometer-sized ionic osmolytes (e.g. Na+ and Cl−) easily diffuse through a micrometer-sized wound. Thus, cells inside the tail fin are bound to experience osmotic pressure changes following wounding in hypotonic bathing medium. The precise amount of interstitial hypotonicity and cell swelling will depend on wound size, wound-opening time, cell-distance from the wound, and efficiency of regulatory volume decrease mechanisms12. In extreme cases, osmotic cell swelling may lead to injury or lysis, which could promote leukocyte recruitment through DAMP-signaling. To test this idea, we wounded zebrafish in hypo- or isotonic medium supplemented with the small, membrane impermeable DNA-dye Sytox-Orange, which enters cells following plasma-membrane damage. DNA-binding enhances Sytox-Orange fluorescence ∼ 500-fold, highlighting damaged or lysed cells. As expected, we frequently detected cell damage along the wound margin, but the tonicity of the medium did not significantly affect the amount of detected damage (Supplementary Fig. S1c). Orthogonally, we wounded fish in the presence of ATP or epithelial cell extract to test if exogenous DAMPs could bypass isotonic inhibition of leukocyte recruitment. Neither of these treatments reconstituted leukocyte recruitment after isotonic injury (Supplementary Fig. S1d). Isotonicity also did not significantly alter epithelial NADPH oxidase (DUOX) activity at the wound margin (Fig. 1d), which was previously identified as a physiological cue necessary for initial leukocyte recruitment 13-16. In conclusion, our data do not provide evidence that cell lysis or cytoplasmic leakage instruct initial leukocyte recruitment in our system, and suggest that additional pathways besides DUOX activation are required.

Cell swelling activates a wide variety of ion channels, tyrosine kinases, and lipases including PLA2 in different cell types12. PLA2 enzymes regulate inflammation and cell volume homeostasis by releasing fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (AA) from the sn-2 position of phospholipids, but how cell swelling activates PLA2 remains unclear12. Secreted (sPLA2) and Ca2+ independent (iPLA2) members of the PLA2 family accept phospholipid substrates of broadly varying sn-2 fatty acid chain length. We therefore focused on cPLA2, which specifically releases the inflammatory mediator AA17. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR on RNA pools from FACS-sorted cell populations of transgenic larvae expressing the far-red fluorescent protein mKate2 in leukocytes indicated uniform cpla2 message expression in leukocyte-enriched and leukocyte-depleted cell fractions (Supplementary Fig. S2a).

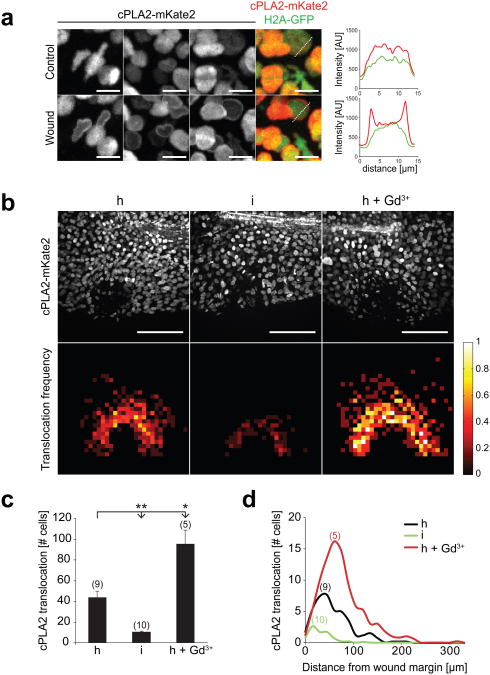

cPLA2 translocation to the nuclear membrane, where key enzymes of AA metabolism (e.g. cyclooxygenases, and lipoxygenases) localize, is associated with phospholipid hydrolysis at that site18, 19 and provides a microscopically tractable, steady-state readout for cPLA2 activation in live cells. cPLA2 was N-terminally fused to mKate2 and the reporter mRNA was injected into one-cell stage embryos. Spinning disk confocal microscopy of live larvae revealed that cPLA2-mKate2 was localized within the nucleus regardless of expression level (Fig. 2a, upper panel) resembling the endogenous cPLA2 localization in proliferating cells 20, 21. Following tail fin wounding with a UV-laser, cPLA2-mKate2 translocated to the nuclear membrane within seconds (Fig. 2a, lower panel; Supplementary Movie 3). The localization and translocation of endogenous cPLA2 was also confirmed by immunofluorescence staining (Supplementary Fig. S2b). We typically observed ∼80% translocation in the first 2-3 rows of wound margin cells and a gradually decreasing translocation frequency over a distance of ∼100-150 μm into the tissue. Larval fin epithelium consists of various cell types 22 and we observed translocation in at least two distinct cell populations, likely epithelial and fibroblast-like cells23, as judged by inspection of nuclear shapes (Fig. 2a, first image column; compare round vs. irregular shaped nuclei).

Fig. 2.

Hypotonicity locally activates cPLA2 at the wound site. (a) Confocal imaging of injury induced cPLA2-mKate2 translocation to nuclear membranes in live zebrafish larvae. Left panel, representative of maximal intensity projections showing cPLA2-mKate2 localization before (upper image panel) or 30 sec after (lower image panel) laser injury of the tail fin. N.b. the cell cytoplasm and cell periphery are not visible, since cPLA2 localizes exclusively to the nucleus. These magnifications were derived from tissue regions near the (prospective) injury site. Outmost right image column, superposition of nuclear H2A-GFP (green) cPLA2-mKate2 (red) fluorescence. Right panel: representative intensity profile plots of H2A-GFP (green) and cPLA2-mKate2 (red) derived from neighbouring image data (dashed lines). Scale bar, 10 μm. (b) Upper panel: full field of view images of cPLA2-mKate2 fluorescence in live tail fins subjected to hypotonic (h), isotonic (i), or hypotonic laser injury in the presence of 500 μM Gd3+ (h+Gd3+) 30 sec post wounding. Lower panel: average cPLA2-mKate2 translocation density projected onto normalized wound coordinates at indicated conditions (see Methods section for details). Colour-scale, relative translocation densities (white=high, red=low, black=none). Scale bar: 100 μm. (c) Average number of nuclei per animal that show cPLA2-mKate2 translocation in response to wounding at indicated conditions. Number of larvae (n) used for the analyses is given in parentheses on the graphs. Error bars: SEM. *: t-test p< 0.05. **: t-test p< 0.005. (d) Average number of nuclei per animal with cPLA2-mKate2 translocation in response to wounding at indicated conditions shown as a function of distance from the wound margin.

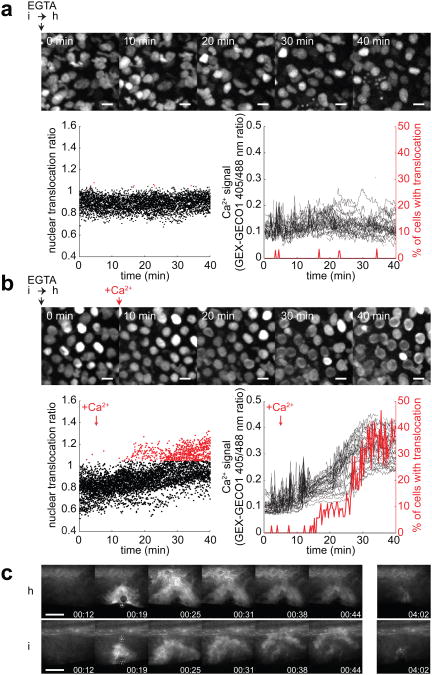

To determine whether cPLA2 translocation depends on cell volume 24-27, fish were wounded in isotonic medium to inhibit osmotic cell swelling. cPLA2-mKate2 translocation was severely inhibited under these conditions (Fig. 2b, c, d). Conversely, we blocked regulatory volume decrease with gadolinium (Gd3+) or ethylene glycol tetra-acetic acid (EGTA) as previously described 28 to augment osmotic cell swelling. Gd3+ exposure enhanced wound margin swelling, as judged by visual inspection of light transmission time-lapse movies (Supplementary Movie 4), and significantly enhanced cPLA2-mKate2 translocation around the injury site (Fig. 2b, right vs. left panel, Fig. 2c, d). By contrast, EGTA treatment completely inhibited cPLA2-mKate2 translocation even in response to hypotonic wounding (Supplementary Movie 5). This is consistent with cPLA2 translocation being Ca2+ dependent 17. Following bath medium supplementation with additional Ca2+ to overcome EGTA mediated extracellular Ca2+ sequestration (after cells were already swollen), cPLA2-mKate2 rapidly translocated to nuclear membranes within the complete field of view (Supplementary Movie 5). Simultaneous imaging of cPLA2-mKate2 translocation and cytoplasmic Ca2+ influx in EGTA treated fish revealed a tight spatiotemporal correlation of both events (Fig. 3a, b). Wound-induced Ca2+ waves have been observed in different tissues across phylae29, 30, but their downstream effectors have remained largely unclear. Tail fin injury rapidly increases cytoplasmic [Ca2+] at the wound site irrespective of medium tonicity (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Movie 6), whereas cPLA2 translocation only occurs under hypotonic conditions. This suggests that in this physiological context, Ca2+ alone is not sufficient to induce cPLA2 activation, which is different from what has been reported in cell culture experiments18. Such co-requirement for Ca2+ and swelling may function as a physiological AND gate to suppress erroneous inflammatory outputs in response to non-correlated fluctuations of [Ca2+] or cell volume in the absence of a wound.

Fig. 3.

Extracellular Ca2+ is required for cPLA2 activation. (a-b) Parallel confocal imaging of cPLA2-mKate2 and cytosolic Ca2+ signals using the GEX-GECO1 Ca2+ indicator in live zebrafish larvae. Larvae were wounded manually in isotonic medium without Ca2+, supplemented with 1mM EGTA and mounted in a small volume of low melting isotonic agarose. Hypotonic medium without Ca2+, supplemented with 1mM EGTA was added on top of the isotonic agar pad at t = 0 min. cPLA2-mKate2 fluorescence (montage) and GEX-GECO1 405nm/488nm excitation ratio images were acquired over the indicated time without (a) or with readdition of CaCl2 to reach a final [Ca2+]free of 0.3 mM at 5 min (b). Left panel, cPLA2-mKate2 perinuclear translocation as a function of time, measured by automatic perinuclear/nuclear fluorescence ratio calculation (see Methods section for details). Points represent individual nuclei with threshold of translocation ratio empirically set to 1.05 (red). Right panel, cytosolic Ca2+ signal of the same cells (left axis) and the percentage of cells with a translocation ratio over 1.05 (right axis, red) as a function of time. Scale bar, 10 μm. (c) Cystosolic Ca2+ measurements in larval tail fins of live zebrafish expressing GCaMP3 during UV-laser induced wounding at 19 sec, under hypotonic (‘h’) or isotonic (‘i’) conditions. Scale bar, 100 μm.

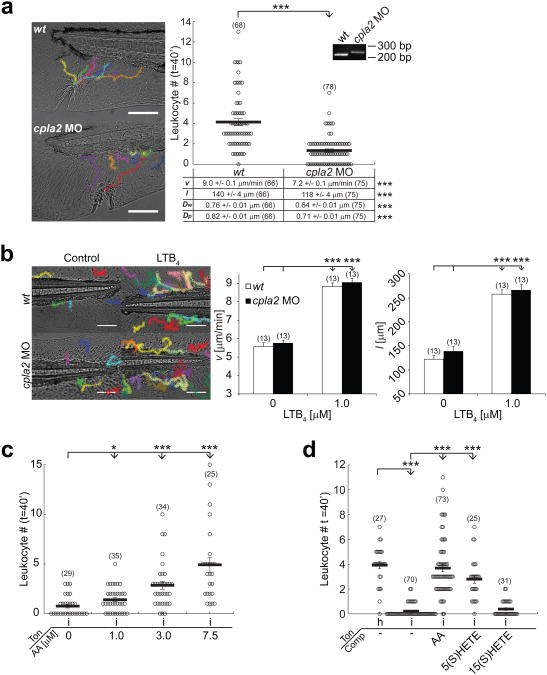

To test if cPLA2 is required for leukocyte recruitment to tail fin wounds, we depleted functional cpla2 message using a splice interfering morpholino. This generated a truncated cpla2 mRNA, and strongly inhibited leukocyte recruitment by impairing both migration velocity and directionality (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Movie 7). Morphant embryos had no morphological defects even at high morpholino concentrations (2-4 pmol/embryo). Leukocyte recruitment in response to bath application of the chemoattractant LTB4 was unperturbed (Fig. 4b), excluding nonspecific and/or permissive effects of cpla2 knockdown. Likewise, leukocyte recruitment in cpla2 morphants was partially rescued by co-injection of mRNA coding for cPLA2-mKate2 (Supplementary Fig. S2c), which also confirms the functionality of our cPLA2 reporter. Non-selective pharmacological inhibition of PLA2 activity with N-(p-amylcinnamoyl) anthranilic acid (ACA) inhibited leukocyte recruitment (Supplementary Fig. S2d), corroborating the morpholino experiments. Together with our translocation data, this suggests that hypotonic swelling activates cPLA2 in cells at the wound margin by a Ca2+-dependent mechanism, and raises the possibility that AA metabolites are involved in leukocyte recruitment.

Fig. 4.

cPLA2 is required for rapid leukocyte recruitment to larval zebrafish tail fin wounds. (a) Average recruitment and migratory parameters of leukocytes within 40 min after tail fin wounding of wt and cpla2 morphant larvae. Inset: RT-PCR on RNA derived from wt and cpla2 morphant larvae using cpla2 specifc primers (b) Migratory parameters (v, l) of leukocytes tracked for 60 min in unwounded wt or cpla2 morphant larvae in response to bath application of LTB4. (c) Leukocyte recruitment to isotonic tail fin incisions at indicated concentrations of arachidonic acid (AA) within 40 min. (d) Leukocyte recruitment (within 40 min) in response to tail fin incisions in hypotonic (‘h’) or isotonic (‘i’) medium tonicities (‘Ton’) in the presence or absence of AA, 5(S)-HETE, or 15(S)-HETE. Indicated compounds (‘Comp’) were used at 5 μM. Number of larvae (n) used for the analyses is given in parentheses on the graphs. Error bars, SEM. *, t-test p< 0.05. **, t-test p< 0.005. ***, t-test p<0.0005. Scale bar, 100 μm.

To explore this possible role of AA metabolites, we attempted to rescue leukocyte recruitment to wounds in the absence of cPLA2 activation, using isotonic medium. AA in the fish medium caused a concentration-dependent rescue of leukocyte recruitment (Fig. 4c), which was similar to the endogenous wound response in terms of speed and radius of leukocyte recruitment. To test if non-specific, biophysical effects (alterations of membrane fluidity, amphiphilic modulation of channel activation, etc.) contribute to AA-induced leukocyte activation, we tested the effect of two structurally related AA downstream metabolites 5(S)- and 15(S)-HETE, which have an additional hydroxyl group at different positions compared to AA. The wound response was reconstituted with 5(S)-HETE, but not by its positional isomer 15(S)-HETE (Fig. 4d). Thus, AA and its metabolite 5(S)-HETE mediate leukocyte migration by a molecule-specific signaling mechanism. Preferential entry through the epithelial barrier breach, or local wound metabolism into different chemotactic species, may explain the ability of these cell-permeable lipids to generate spatially instructive wound cues following uniform application in fish bathing solution.

The small tissue size rendered biochemical quantification of local AA production and oxidation in wounded tail fin tips impossible. AA oxidation can occur via enzymatic or non-enzymatic routes. A gross pharmacological characterization of the enzymes known to act on AA indicated a possible role for 5-lipoxygenase (ALOX5), but not cyclooxygenases or LTA4 hydrolase (LTA4H) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Concordant with studies showing leukotriene precursor production by non-myeloid cells of the skin31, 32, and ubiquitous alox5 mRNA expression in embryonic zebrafish33, we detected alox5 message both in leukocytes and leukocyte-depleted tissue (Supplementary Fig. S3f). These experiments indicated the participation of chemotactic lipoxygenase metabolites other than classic LTA4H-derived leukotrienes.

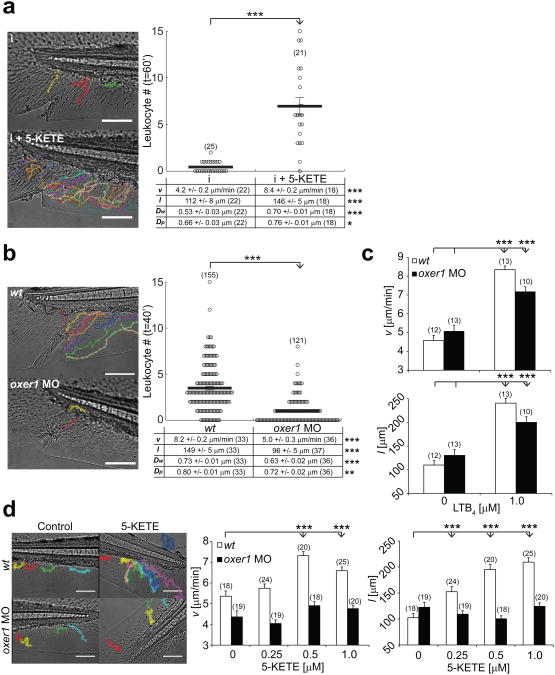

The ALOX5 product 5(S)-HETE can undergo oxidation to 5-KETE (also termed 5-oxo-ETE) by 5-hydroxyeicosanoid dehydrogenase in various cell types including myeloid and epithelial cells34. The non-canonical eicosanoid 5-KETE is a potent neutrophil and eosinophil chemoattractant in mammals35, but its physiological role remains little understood. Confirming its chemoattractive function in zebrafish, addition of 5-KETE to isotonic tail fin wounds restored dynamic parameters and recruitment of leukocytes to hypotonic control levels (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Movie 8). In human cells, 5-KETE signals via a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) termed OXE-R. To investigate if OXE-R signaling contributes to the zebrafish wound response, we identified in the zebrafish genome a predicted GPCR gene and ortholog to human OXE-R (OXER1), henceforth referred to as oxer1 (GPR81-4, ENSDARG00000087084). FACS sorting and semi-quantitative RT-PCR revealed that oxer1 mRNA was robustly expressed both in leukocytes and leukocyte depleted tissue (Supplementary Fig. S4d). Oxer1 knockdown with a translation blocking morpholino inhibited leukocyte recruitment to tail fin wounds by reducing leukocyte migration velocity and directionality (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Movie 9), while it did not significantly affect embryo survival or gross morphology even at high morpholino concentrations (∼ 2 pmol/embryo). To probe for potential morpholino off-target effects and permissive functions of OXE-R, we quantified leukocyte migration in unwounded fish in response to bath application of LTB4. LTB4 produced strong migration in both wt and oxer1 morphant fish (Fig. 5c). By contrast, migration in response to bath application of 5-KETE was blocked only in oxer1 morphants, but not in wt embryos (Fig. 5d). Receptor desensitization by prolonged preincubation with exogenous 5-KETE significantly reduced hypotonic (i.e. control) wound recruitment of leukocytes (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Leukocyte chemotaxis to isotonic wounds in response to bath application of AA was also inhibited in oxer1 morphants (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Together, these data suggest that zebrafish OXE-R mediates 5-KETE and AA responses, and rapid, endogenous leukocyte recruitment to tail fin wounds.

Fig. 5.

OXE-R is required for rapid leukocyte recruitment to larval zebrafish tail fin wounds. (a) Average recruitment and migratory parameters of leukocytes within 60 min after isotonic tail fin wounding of wt larvae in the presence or absence of 2 μM 5-KETE in the supernatant medium (see Methods section for details). (b) Average recruitment and migratory parameters of leukocytes within 40 min after hypotonic tail fin wounding of wt and oxer1 morphant larvae. (c) Migratory parameters (v, l) of leukocytes tracked for 60 min in unwounded wt or oxer1 morphant larvae in response to bath application of LTB4. (d) Migratory parameters of leukocytes tracked for 60 min in unwounded wt or oxer1 morphant larvae in response to bath application of 5-KETE. Number of larvae (n) used for the analyses is given in parentheses on the graphs. Error bars, SEM. *, t-test p< 0.05. **, t-test p< 0.005. ***, t-test p<0.0005. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Activation of the epithelial NADPH oxidase DUOX at the wound site is necessary for rapid leukocyte chemotaxis13. Isotonic inhibition of cPLA2 activation, as well as cpla2 and oxer1 knockdown inhibit leukocyte recruitment, but not NADPH oxidase activity at the wound margin (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. S4e). This indicates that DUOX activation alone is not enough to trigger leukocyte chemotaxis, and we now show that osmotically-induced production of AA is also required. Oxo-eicosanoids, such as 5-KETE, are preferentially produced in response to oxidative stress e.g. caused by H2O2 or cytoplasmic NADPH depletion, respectively34. Thus, it is possible that DUOX activity, which generates extracellular H2O2 by consuming cytoplasmic NADPH, mediates tissue damage detection by promoting production of oxidized, chemotactic AA metabolites at the wound site, besides directly signaling to leukocytes through extracellular H2O2 14, 36, 37 (Supplementary Fig. S5).

We have demonstrated the existence of an osmotic signaling circuit that directly monitors tissue barrier integrity. In contrast to current danger signaling paradigms, our findings suggest that tissues can sense injury even in the absence of dead cells by harnessing cell swelling as pro-inflammatory intermediate. Some human pathologies, e.g. cystic fibrosis, cause defective cell volume homeostasis38 and inflammation. Tissue-necrosis (e.g. during ischemia) produces excessive cell swelling and leukocyte recruitment39. Leukocyte necrotaxis has been typically linked to cytoplasmic leakage. Given our results, leakage-independent contributions of necrotic cell swelling, which generally precedes necrotic lysis, warrant closer investigation.

Osmotic surveillance of barrier integrity probably evolved in freshwater organisms to ensure reliable detection and safeguarding of epithelial breaches. Those present major infection risks, but can easily occur with minimal cell-death. Notably, major parts of the upper digestive tract, and potentially also the lungs3, 4 of land living mammals are covered with hypotonic fluid. Human saliva is initially isotonic, and becomes desalted by ductal passage. Although the tonicity of lung fluid is debated40, it is clear that our bodies establish a freshwater-like environment (saliva: ∼30 mOsm) within the oral cavity and esophagus. The physiological purpose of this remains unclear, but it is conceivable that luminal hypotonicity presents part of an ancestral barrier defense mechanism of wet epithelia that proved useful during evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Mitchison, Alan Hall, Michael Overholtzer, and András Kapus for their valuable thoughts and suggestions on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant GM099970 and a Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. Young Investigator award.

Footnotes

Author contributions: P.N. conceived the project. B.E. and P.N. designed the experiments. B.E., P.N., S.K., and T.N.Z. performed the experiments. P.N. and B.E. wrote the paper.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Seong SY, Matzinger P. Hydrophobicity: an ancient damage-associated molecular pattern that initiates innate immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:469–478. doi: 10.1038/nri1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao M, et al. Electrical signals control wound healing through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase-gamma and PTEN. Nature. 2006;442:457–460. doi: 10.1038/nature04925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilljam H, Ellin A, Strandvik B. Increased bronchial chloride concentration in cystic fibrosis. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1989;49:121–124. doi: 10.3109/00365518909105409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joris L, Dab I, Quinton PM. Elemental composition of human airway surface fluid in healthy and diseased airways. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1633–1637. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redd MJ, Cooper L, Wood W, Stramer B, Martin P. Wound healing and inflammation: embryos reveal the way to perfect repair. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological sciences. 2004;359:777–784. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huttenlocher A, Poznansky MC. Reverse leukocyte migration can be attractive or repulsive. Trends in cell biology. 2008;18:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renshaw SA, Trede NS. A model 450 million years in the making: zebrafish and vertebrate immunity. Disease models & mechanisms. 2012;5:38–47. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieschke GJ, Trede NS. Fish immunology. Current biology: CB. 2009;19:R678–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberts B, et al. Molecular biology of the cell. 4th. Garland Science; New York: 2002. supplementary movie entitled “Leukocytes homing to fin wound” by Redd, M.J. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathias JR, et al. Resolution of inflammation by retrograde chemotaxis of neutrophils in transgenic zebrafish. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2006;80:1281–1288. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van't Hoff JH. The role of osmotic pressure in the analogy between solutions and gases. Journal of Membrane Science. 1995;100:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiological reviews. 2009;89:193–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niethammer P, Grabher C, Look AT, Mitchison TJ. A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature. 2009;459:996–999. doi: 10.1038/nature08119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoo SK, Starnes TW, Deng Q, Huttenlocher A. Lyn is a redox sensor that mediates leukocyte wound attraction in vivo. Nature. 2011;480:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature10632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreira S, Stramer B, Evans I, Wood W, Martin P. Prioritization of competing damage and developmental signals by migrating macrophages in the Drosophila embryo. Current biology: CB. 2010;20:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng Y, Santoriello C, Mione M, Hurlstone A, Martin P. Live imaging of innate immune cell sensing of transformed cells in zebrafish larvae: parallels between tumor initiation and wound inflammation. PLoS biology. 2010;8:e1000562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke JE, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 structure/function, mechanism, and signaling. Journal of lipid research. 2009;50 Suppl:S237–242. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800033-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glover S, et al. Translocation of the 85-kDa phospholipase A2 from cytosol to the nuclear envelope in rat basophilic leukemia cells stimulated with calcium ionophore or IgE/antigen. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:15359–15367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peters-Golden M, Song K, Marshall T, Brock T. Translocation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 to the nuclear envelope elicits topographically localized phospholipid hydrolysis. The Biochemical journal. 1996;318(Pt 3):797–803. doi: 10.1042/bj3180797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sierra-Honigmann MR, Bradley JR, Pober JS. “Cytosolic” phospholipase A2 is in the nucleus of subconfluent endothelial cells but confined to the cytoplasm of confluent endothelial cells and redistributes to the nuclear envelope and cell junctions upon histamine stimulation. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1996;74:684–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grewal S, Morrison EE, Ponnambalam S, Walker JH. Nuclear localisation of cytosolic phospholipase A2-alpha in the EA.hy.926 human endothelial cell line is proliferation dependent and modulated by phosphorylation. Journal of cell science. 2002;115:4533–4543. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien GS, et al. Coordinate development of skin cells and cutaneous sensory axons in zebrafish. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2012;520:816–831. doi: 10.1002/cne.22791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mateus R, et al. In vivo cell and tissue dynamics underlying zebrafish fin fold regeneration. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thoroed SM, Lauritzen L, Lambert IH, Hansen HS, Hoffmann EK. Cell swelling activates phospholipase A2 in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. The Journal of membrane biology. 1997;160:47–58. doi: 10.1007/s002329900294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basavappa S, Pedersen SF, Jorgensen NK, Ellory JC, Hoffmann EK. Swelling-induced arachidonic acid release via the 85-kDa cPLA2 in human neuroblastoma cells. Journal of neurophysiology. 1998;79:1441–1449. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen S, Lambert IH, Thoroed SM, Hoffmann EK. Hypotonic cell swelling induces translocation of the alpha isoform of cytosolic phospholipase A2 but not the gamma isoform in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. European journal of biochemistry/FEBS. 2000;267:5531–5539. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vriens J, et al. Cell swelling, heat, and chemical agonists use distinct pathways for the activation of the cation channel TRPV4. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:396–401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303329101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hua SZ, Gottlieb PA, Heo J, Sachs F. A mechanosensitive ion channel regulating cell volume. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2010;298:C1424–1430. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00503.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Razzell W, Evans IR, Martin P, Wood W. Calcium flashes orchestrate the wound inflammatory response through DUOX activation and hydrogen peroxide release. Current biology: CB. 2013;23:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sieger D, Moritz C, Ziegenhals T, Prykhozhij S, Peri F. Long-range Ca2+ waves transmit brain-damage signals to microglia. Developmental cell. 2012;22:1138–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kowal-Bielecka O, et al. Evidence of 5-lipoxygenase overexpression in the skin of patients with systemic sclerosis: a newly identified pathway to skin inflammation in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2001;44:1865–1875. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)44:8<1865::AID-ART325>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo M, Lee S, Brock TG. Leukotriene synthesis by epithelial cells. Histology and histopathology. 2003;18:587–595. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cannon JE, et al. Global analysis of the haematopoietic and endothelial transcriptome during zebrafish development. Mechanisms of development. 2013;130:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant GE, Rokach J, Powell WS. 5-Oxo-ETE and the OXE receptor. Prostaglandins & other lipid mediators. 2009;89:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell WS, Chung D, Gravel S. 5-Oxo-6,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid is a potent stimulator of human eosinophil migration. Journal of immunology. 1995;154:4123–4132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klyubin IV, Kirpichnikova KM, Gamaley IA. Hydrogen peroxide-induced chemotaxis of mouse peritoneal neutrophils. European journal of cell biology. 1996;70:347–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuiper JW, Sun C, Magalhaes MA, Glogauer M. Rac regulates PtdInsP(3) signaling and the chemotactic compass through a redox-mediated feedback loop. Blood. 2011;118:6164–6171. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-310383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valverde MA, et al. Impaired cell volume regulation in intestinal crypt epithelia of cystic fibrosis mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:9038–9041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jennings RB, Reimer KA. The cell biology of acute myocardial ischemia. Annual review of medicine. 1991;42:225–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.42.020191.001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsui H, et al. Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell. 1998;95:1005–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.