Abstract

Objectives

This study was conducted to examine the therapeutic efficacy and anti-inflammatory effect of ramelteon in elderly patients with insomnia associated with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), who visited our urology department.

Methods

The study included 115 patients (102 men, 13 women) who scored ≥4 on the Athens Insomnia Scale and who wished to receive treatment. The assessment scales for therapeutic efficacy included the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) for LUTS and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) for sleep disorders. The high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) test was used to an objective assessment. The patients were treated with ramelteon (8 mg/day) for an average of 10 weeks and were then reexamined using the questionnaires and hs-CRP test to evaluate therapeutic efficacy.

Results

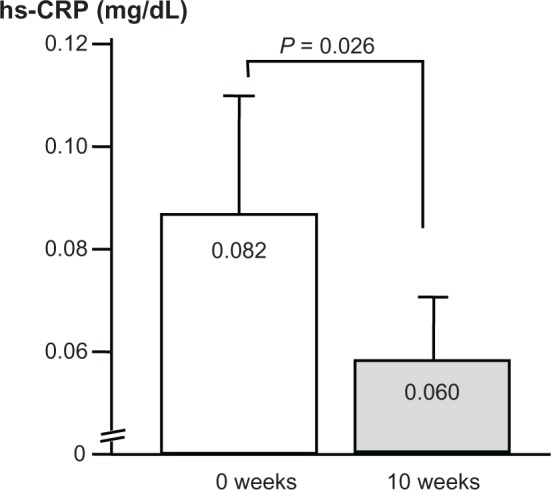

IPSS total scores declined significantly from 11.39 ± 8.78 to 9.4 ± 7.72. ISI total scores improved significantly from 11.6 ± 5.2 to 9.2 ± 5.3 (P < 0.0001). The levels of hs-CRP decreased significantly from 0.082 (standard deviation [SD] upper limit, 0.222; SD lower limit, −0.059) to 0.06 (SD upper limit, 0.152; SD lower limit, −0.032). The ISI scores ≥ 10 (n = 51) showed a weak correlation with the hs-CRP levels.

Conclusion

Ramelteon had a systemic anti-inflammatory effect and improved sleep disorders and LUTS, suggesting that it may be a useful treatment for patients with LUTS-associated insomnia.

Keywords: sleep disorders, inflammation, lower urinary tract symptoms, ramelteon

Introduction

In today’s society of high stress and nightshift work, there has been a surge in the number of people who suffer from insomnia or disturbed body rhythm, to the point where one out of five Japanese individuals complains of sleep disorder.1 A study by the Institute of Public Health (now the National Institute of Public Health) showed that approximately one in 20 people had used sleeping pills in the previous month, with particularly high rates found among elderly individuals.2 Sleep disorders can cause deterioration in the quality of life (QOL), induce inflammation, and put individuals at risk of developing lifestyle-related diseases and specifically, cardiovascular diseases.3,4

We previously reported that lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and sleep disorders are closely related; the prevalence of the two increases as the population ages, and high LUTS scores are associated with a high prevalence of sleep disorders.5 Benzodiazepines (mainstream sleeping drugs) have a muscle relaxant effect that can result in staggering and falling. These adverse effects can last through the following morning, requiring that particular caution be exercised in elderly patients, who tend to have a number of complications, such as nocturia. In fact, there have been reports of an increased death rate from staggering-associated falls, in people who rise to urinate during the night.6,7 Urination-related arousal has also been argued to compromise sleep quality in the elderly.8

Ramelteon, a melatonin receptor (MT) agonist, is a drug with a novel mechanism of action. It induces sleep not through sedative action but rather, by adjusting the sleep–wake rhythm. The use of ramelteon has not induced staggering in elderly patients with insomnia.9 We previously used ramelteon to increase the nighttime bladder capacity of patients with nocturia-induced insomnia and found that it successfully reduced the number of nocturnal voids and improved sleep disorders.10 There has been only one study in which the use of ramelteon resulted in the improvement of both nocturia and overall LUTS.10 However, body rhythm disturbances caused by irregular shifts at work have been reported to result in inflammation induced by transient sleep disorders.11 Thus, in the present study, we administered ramelteon to patients with LUTS-associated insomnia to examine the drug’s ability to improve sleep disorders and LUTS, and we used an inflammatory marker – high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) – to evaluate the objective findings.

Subjects and methods

This was an open and nonrandomized study. The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)12 and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS)13 questionnaires were approved by the ethics committee of Kinki University. Consent was obtained from patients before the start of the study. Study subjects were selected from among those who received outpatient treatment at the Department of Urology, Kinki University Faculty of Medicine, between November 2011 and May 2012 and who complained of insomnia, with an Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS)14 score ≥ 4, for which they wished to receive treatment while continuing on their current therapy. The study included 115 patients (102 men, mean age 72.5 ± 10.0 years; and 13 women, mean age 70.5 ± 8.0 years), from whom the interview sheet could be collected before and after ramelteon treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with insomnia and lower urinary tract symptoms

| Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| n | 115 |

| Gender: male/female | 102/13 |

| Age (years) | 72.3 ± 9.8 |

| IPSS total | 11.39 ± 8.78 |

| AIS | 6.4 ± 3.6 |

| ISI | 11.6 ± 5.2 |

| Study period (weeks) | 10.3 ± 5.1 |

| Characteristics of patients | |

| BPH | 47 |

| Prostate cancer | 34 |

| Overactive bladder | 47 |

| Neurogenic bladder | 2 |

| Nocturia only | 16 |

Notes: Values are expressed as means ± SD.

Abbreviations: AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; SD, standard deviation.

The subjects took one 8 mg ramelteon tablet once a day for 10 weeks.. Because ramelteon, as a melatonin receptor agonist, has a mechanism of action that is completely different from that of existing benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines, the study allowed its concomitant use with other hypnotic agents, and no changes were made to the subjects’ existing treatment regimens during the evaluation period. In addition, when combined, the dose of the α1-blocker and the anticholinerigic drugs targeting LUTS remained unaltered during the evaluation period. Patients who had a history of hypersensitivity to ramelteon, severe hepatic dysfunction, or who were currently taking fluvoxamine, were excluded from the study.

Sleep disorders

Subjects were first evaluated for the use of a hypnotic agent and were then evaluated with the AIS, a scale developed in the Worldwide Project on Sleep and Health that was launched by the World Health Organization. The scale scores were interpreted as: ≤4, no concern about sleep disorder; 4–5, sleep disorder slightly suspected; and ≥6, sleep disorder suspected. Subjects were assessed using the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, second edition (ICSD-2)15 to determine whether they had any of the following: subjective insomnia; presence of insomnia within an environment suited for sleep; and functional impairments during the day (eg, daytime sleepiness, impaired attentive ability, and impaired concentration). An evaluation of insomnia improvement was then performed using a questionnaire survey that was based on a combination of the ISI and a subjective symptom improvement scale investigating: ease of falling asleep, arousal during nighttime sleep, the presence of a refreshed feeling in the morning, daytime drowsiness, and staggering. Sleeping disorders were classified into four types: (1) insomnia; (2) hypersomnia; (3) sleep apnea; and (4) circadian rhythm disorder. This study focused only on the evaluation of insomnia.

LUTS

The IPSS is an eight-question (seven symptom questions plus one QOL question) written screening tool that was designed to screen for, rapidly diagnose, track the symptoms of, and propose the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). It is currently used to evaluate BPH and a wide range of other LUTS in both men and women. The seven symptom questions probe: feeling of incomplete emptying; daytime frequency; intermittency; urgency; slow stream; hesitancy; and nocturia. These questions refer to the period during the previous month and are rated on a scale of 1–5 for a maximum of 35 points. The QOL question is assigned a score of 1–6. Total scores of 0–7 represent mild symptoms, 8–9 represent moderate symptoms, and ≥20 represent severe symptoms.

QOL

The QOL subscale (0, delighted; 1, pleased; 2, mostly satisfied; 3, mixed; 4, mostly dissatisfied; 5, unhappy; and 6, terrible) of the IPSS questionnaire was also used.

Evaluation of inflammation

For patients whose hs-CRP levels could be measured biochemically before and after ramelteon treatment, the association between inflammation and improvements in sleep disorders and LUTS was examined. When we were able to collect blood at other opportunities, we used this CRP data instead. While a urinary tract infection was not present in any of these cases, information about potential confounding variables (eg, smoking, hypertension, and diabetes) was collected. A 7700 Hitachi Automatic Analyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used to measure hs-CRP.

Statistical analysis

The PASW Statistics 18.02 software package for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. Changes in IPSS scores, QOL subscores, and ISI scores were evaluated using the Wilcoxon test, whereas the correlation between the ISI and IPSS scores was evaluated using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Geometric means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for hs-CRP levels as a measure of the anti-inflammatory effect. A paired t-test was performed to evaluate the relationship between changes in ISI scores and changes in hs-CRP levels. The relationship between the changes in IPSS scores and the changes in hs-CRP levels was evaluated using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

Results

The primary underlying disease was prostatic hyperplasia in 47 subjects, prostate cancer in 34 subjects, overactive bladder in 47 subjects, and neurogenic bladder in two subjects, while 16 subjects had nocturia only (Table 1). The total number of these subjects exceeded 115 because some subjects had comorbidities. Fifty-two patients had difficulty falling asleep, 72 were aroused during sleep, 72 had problem waking up too early, and seven were dissatisfied with sleep.

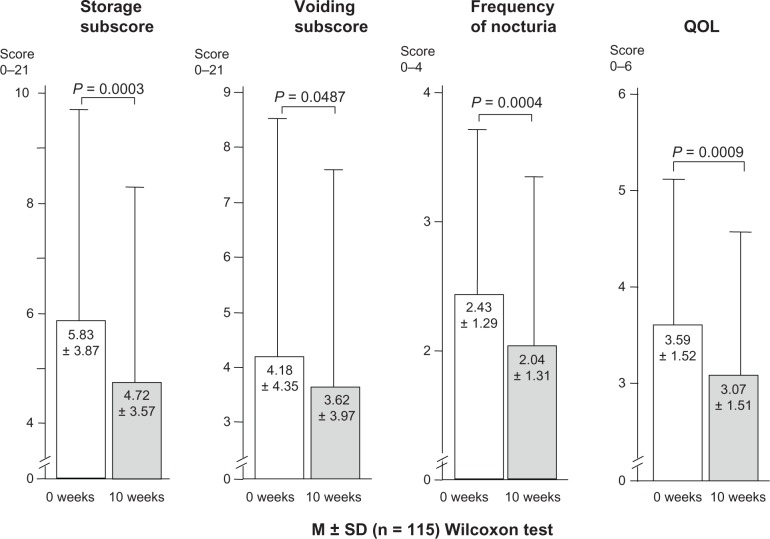

Changes in IPSS scores and QOL subscores

The IPSS total scores declined from 11.39 ± 8.78 to 9.4 ± 7.72 (P = 0.0013). Significant improvements were observed in the scores for storage symptoms (frequency + urgency + noctuira), which declined from 5.83 ± 3.87 to 4.72 ± 3.57 (P = 0.0003); voiding symptoms (intermittency + slow stream + hesitancy), which changed from 4.18 ± 4.35 to 3.62 ± 3.97 (P = 0.0487); nocturia, which changed from 2.43 ± 1.29 to 2.04 ± 1.31 (P = 0.0004); and QOL, which changed from 3.59 ± 1.52 to 3.07 ± 1.51 (P = 0.0009) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in storage subscores, voiding subscores, nocturia frequency, and quality of life before and after ramelteon administration.

Notes: Values were expresses as mean ± SD (n = 115), Wilcoxon test. IPSS storage subscores were based on daytime frequency + urgency + nocturia; IPSS voiding subscores were based on intermittency + slow stream + hesitancy.

Abbreviations: IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; QOL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

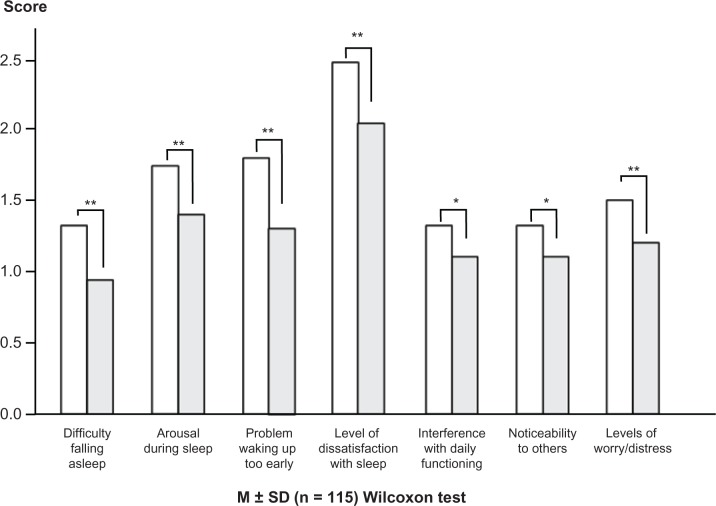

Changes in ISI scores

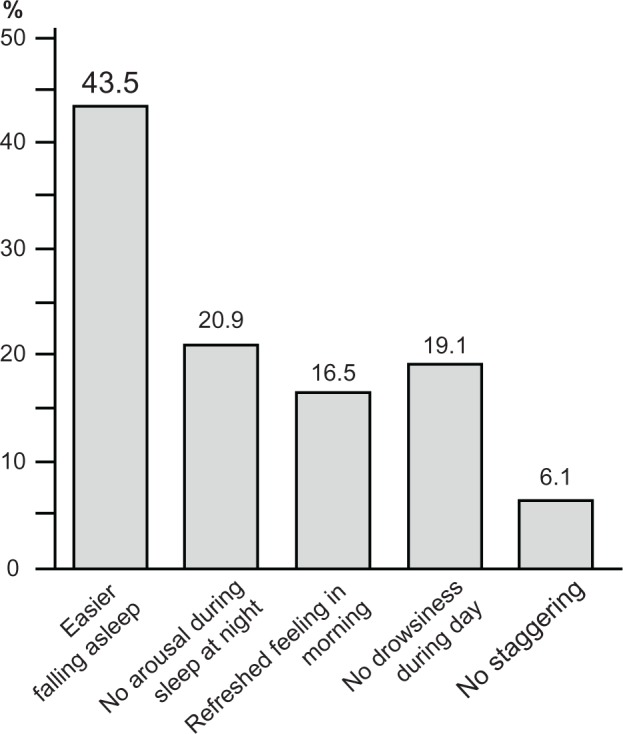

Significant improvements were observed in the scores for: (1) difficulty falling asleep, which changed from 1.3 ± 1.0 to 0.9 ± 0.9 (P = 0.0002); (2) arousal during sleep, which changed from 1.7 ± 1.0 to 1.4 ± 1.0 (P = 0.0021); (3) waking up too early, which changed from 1.8 ± 1.2 to 1.3 ± 1.1 (P < 0.0001); (4) level of dissatisfaction with sleep, which changed from 2.5 to 2.1 (P < 0.0001); (5) interference with daily functioning, which changed from 1.3 to 1.1 (P = 0.0128); (6) noticeability to others, which changed from 1.3 to 1.1 (P = 0.0289); (5) the level of worry/distress, which changed from 1.5 ± 0.28 to 1.2 ± 1.0 (P = 0.0003); and for (7) the total score, which changed from 11.6 ± 5.2 to 9.2 ± 5.3 (P < 0.0001) (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Change in ISI score before and after ramelteon administration.

Notes: Significant improvements were observed in all categories. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 (vs 0 weeks).

Abbreviations: ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 3.

The percentage of patients showing improvement for each category.

Note: Values were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 115), Wilcoxon test.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

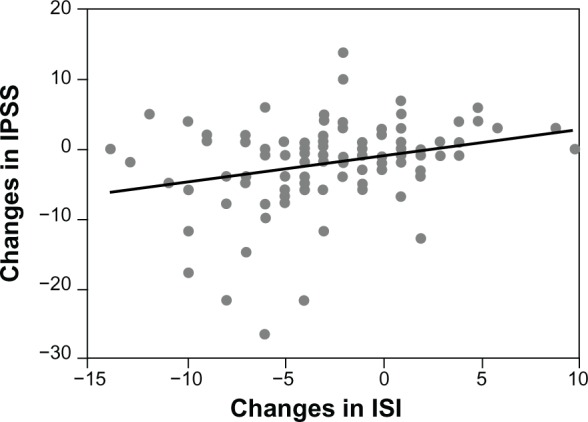

Correlation between ISI and IPSS scores

A weak correlation (r = 0.278) was observed between the changes in the ISI and IPSS scores (P = 0.0026) (Figure 4). The score of patients arousing during sleep correlated with the amount of residual urine (r = 0.414, P < 0.0001), disrupted urine flow (r = 0.434, P < 0.0001), and voiding (r = 0.460, P < 0.0001) subscores. The scores of patients dissatisfied with sleep showed correlation with the amount of residual urine (r = 0.434, P < 0.0001), the daytime urinary frequency (r = 0.459, P < 0.0001), disrupted urine flow (r = 0.428, P < 0.0001), voiding (r = 0.429, P < 0.0001), and storage (r = 0.447, P < 0.0001) subscores. The nocturia score also correlated with the subscore of patients dissatisfied with their sleep (r = 0.295, P < 0.0014).

Figure 4.

Correlation between ISI and IPSS scores.

Notes: Spearman rank correlation coefficient, r = 0.278; P = 0.0026.

Abbreviations: IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index.

Anti-inflammatory effect

The changes in hs-CRP levels are shown in Figure 5. The geometric mean before treatment was 0.082 (SD upper limit, 0.222; SD lower limit, −0.059), which declined significantly by 26.8% to 0.06 (SD upper limit, 0.152; SD lower limit, −0.032) after treatment (P = 0.026).

Figure 5.

Changes in hs-CRP levels.

Note: n = 51.

Abbreviation: hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein.

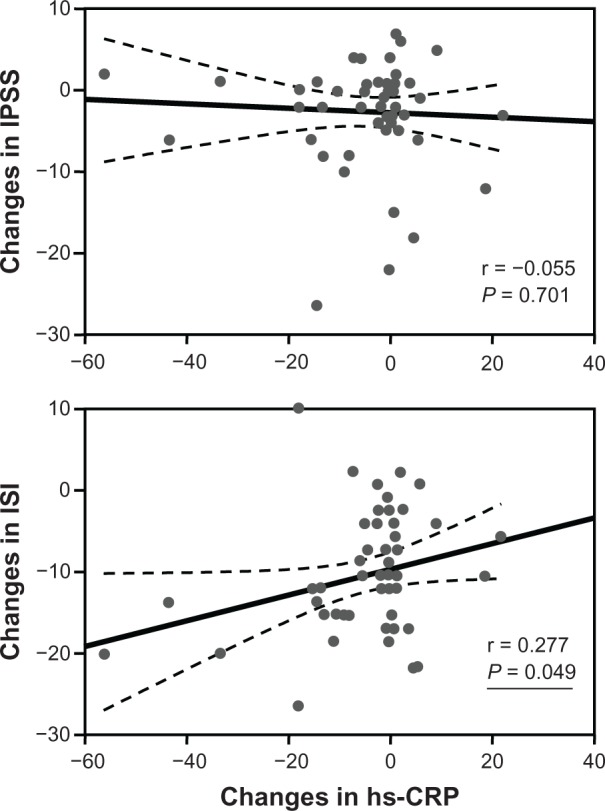

The changes in ISI scores and in hs-CRP levels were not significantly correlated among all subjects (n = 77); however, a weak correlation was observed in the population diagnosed with insomnia, namely, those that scored ≥ 10 on the ISI scale (n = 51). No significant correlation was observed between changes in IPSS scores and changes in hs-CRP levels (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Association between changes in IPSS or ISI scores and changes in hs-CRP levels.

Abbreviations: hs-CRP, high sensitivity C-reactive protein; IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index.

Discussion

In the present study, ISI total scores significantly declined from 11.6 ± 5.2 to 9.2 ± 5.3, below the pathological threshold cut-off point of 10. This finding demonstrated the effect of ramelteon in improving sleep disorders, with significant improvements observed in storage symptoms, voiding symptoms, nocturia, and QOL. This study also found that ramelteon treatment improved sleep quality, which in turn improved LUTS. Although the mechanism for the improvement of these symptoms is not yet clear, it is presumably related to LUTS and sleep disorders, as shown by an earlier report that the bladder has a “body clock” that is responsible for the circadian rhythm in urine collection, while clock genes are involved in the circadian rhythm in voiding.16

Ramelteon treatment significantly reduced hs-CRP levels by 26.8%. Inflammation and oxidation are closely related, and the antioxidant effect of melatonin is thought to be a direct result of its potent radical-scavenging ability, although recent reports have also suggested that the effect occurs via the MT receptor.17,18 It has also been reported that ramelteon, which shows high affinity only for the MT1 and MT2 receptors, improved hepatic function and liver perfusion in models of hepatic dysfunction caused by hemorrhagic shock, even though it was not shown to have direct antioxidant effect.19 The same report also confirmed that at least part of the effect was mediated by MT receptors and that ramelteon reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), which is involved in oxidative stress. Based on these reports, we believe that the declines seen in hs-CRP levels in the present study may have involved an antioxidant effect caused by MT receptor stimulation.

It has been reported that transient sleep disorders caused by body rhythm disturbances owing to irregular shifts at work induce inflammation.11 The significant correlation between ISI scores and hs-CRP levels obtained in subjects who scored ≥ 10 on the ISI scale, namely, those who were above the pathological threshold, suggests that the ramelteon treatment–induced sleep-quality improvements may have indirectly induced the anti-inflammatory effect. A report from a study conducted in 1452 Chinese men showed an association between hs-CRP levels and LUTS, in which the higher the former, the more severe was the latter.20 The present study did not find a definitive correlation between changes in hs-CRP levels and changes in IPSS scores; this may have been because hs-CRP levels are not determined solely by LUTS but are affected by systemic conditions, or may have been the result of differences in patient demographics or the small number of subjects. The study was not placebo controlled and a placebo effect cannot be completely excluded. Since the LUTS examination was only a subjective evaluation, an objective examination of the effect of uroflometry is required.

Conclusion

Ramelteon had a systemic anti-inflammatory effect and improved both sleep disorders and LUTS. These results suggest that ramelteon may be a useful treatment option for patients with LUTS-associated insomnia.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Kim K, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Liu X, Ogihara R. An epidemiological study of insomnia among the Japanese general population. Sleep. 2000;23(1):41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doi Y, Minowa M, Okawa M, Uchiyama M. Prevalence of sleep disturbance and hypnotic medication use in relation to sociodemographic factors in the general Japanese adult population. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(2):79–86. doi: 10.2188/jea.10.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaneita Y, Uchiyama M, Yoshiike N, Ohida T. Associations of usual sleep duration with serum lipid and lipoprotein levels. Sleep. 2008;31(5):645–652. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(12):1484–1492. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu N, Nagai Y, Yamamoto Y, et al. Survey on lower urinary tract symptoms and sleep disorders in patients treated at urology departments. Nat Sci Sleep. 2013;5:7–13. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S40618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakagawa H, Niu K, Hozawa A, et al. Impact of nocturia on bone fracture and mortality in older individuals: a Japanese longitudinal cohort study. J Urol. 2010;184(4):1413–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupelian V, Fitzgerald MP, Kaplan SA, Norgaard JP, Chiu GR, Rosen RC. Association of nocturia and mortality: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Study. J Urol. 2011;185(2):571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asplund R. Nocturia in relation to sleep, health, and medical treatment in the elderly. BJU Int. 2005;96(Suppl 1):S15–S21. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zammit G, Wang-Weigand S, Rosenthal M, Peng X. Effect of ramelteon on middle-of-the-night balance in older adults with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(1):34–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu N, Sugimoto K, Nozawa M, et al. The efficacy of ramelteon in patients with insomnia and nocturia. LUTS. 2013;5(2):69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-5672.2012.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rauchenzauner M, Ernst F, Hintringer F, et al. Arrhythmias and increased neuro-endocrine stress response during physicians’ night shifts: a randomized cross-over trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(21):2606–2613. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ThaBastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barry MJ, Fowler FJ, Jr, O’Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148:1549–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. discussion 1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. The diagnostic validity of the Athens Insomnia Scale. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(3):263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00604-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. 2nd ed. Rochester, MN: Sleep Disorders Association; 2005. (ICSD-2) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Negoro H, Kanematsu A, Doi M, et al. Involvement of urinary bladder Connexin43 and the circadian clock in coordination of diurnal micturition rhythm. Nat Commun. 2012;3:809. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez C, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, et al. Regulation of antioxidant enzymes: a significant role for melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2004;36(1):1–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-079x.2003.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomás-Zapico C, Coto-Montes A. A proposed mechanism to explain the stimulatory effect of melatonin on antioxidative enzymes. J Pineal Res. 2005;39(2):99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathes AM, Kubulus D, Waibel L, et al. Selective activation of melatonin receptors with ramelteon improves liver function and hepatic perfusion after hemorrhagic shock in rat. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2863–2870. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318187b863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu Z, Gao Y, Tan A, et al. Increased high-sensitivity C-reactive protein predicts a high risk of lower urinary tract symptoms in Chinese male: Results from the Fangchenggang Area Male Health and Examination Survey. Prostate. 2012;72(2):193–200. doi: 10.1002/pros.21421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]