Abstract

Background

Although heart failure (HF) is a syndrome with important differences in response to therapy by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), existing risk stratification models typically group all HF patients together. The relative importance of common predictor variables for important clinical outcomes across strata of LVEF is relatively unknown.

Methods and Results

We identified all members with HF between 2005 and 2008 from 4 integrated health care systems in the Cardiovascular Research Network. LVEF was categorized as preserved (LVEF ≥50% or normal), borderline (41-49% or mildly reduced), and reduced (≤40% or moderately to severely reduced). We used Cox regression models to identify independent predictors of death and hospitalization by LVEF category. Among 30,094 ambulatory adults with HF, mean age was 74 years and 46% were women. LVEF was preserved in 49.5%, borderline in 16.2%, and reduced in 34.3% of patients. Over a median follow up of 1.8 years (IQR 0.8-3.1), 8,060 (26.8%) patients died, 8,108 (26.9%) were hospitalized for HF, and 20,272 (67.4%) were hospitalized for any reason. In multivariable models, nearly all tested covariates performed similarly across LVEF strata for the outcome of death from any cause, as well as for HF-related and all-cause hospitalizations.

Conclusions

We found that in a large, diverse contemporary HF population, risk assessment was strikingly similar across all LVEF categories. These data suggest that, although many HF therapies are uniquely applied to patients with reduced LVEF, individual prognostic factor performance does not appear to be significantly related to level of left ventricular systolic function.

Keywords: heart failure, outcomes, prognosis, risk factor

Heart failure (HF) is associated with high morbidity and mortality,1 but prognosis can vary significantly between individual patients. Accurate risk stratification is important for understanding patient factors associated with poor outcomes and, by extension, communicating expectations with patients, identifying potential targets for intervention, tailoring the intensity of care decisions, and creating risk-standardized outcomes measures.2

While several different HF prognostic models have been published,3-9 existing models are limited by several factors, including a lack of standardization in the choice and evaluation of candidate predictor variables, derivation and validation within narrow patient cohorts, and a focus on death alone as the outcome of interest. As a consequence, we have limited insights into how various factors relate to prognosis across different categories of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) for both fatal and non-fatal endpoints. With the changing epidemiology of HF over the past several decades, the majority of patients with HF in the United States now have preserved LVEF (HF-PEF) rather than reduced LVEF (HF-REF).10 While HF-PEF patients have high rates of adverse outcomes,11, 12 there are very limited clinical trial data to guide treatment in these patients. Another notable knowledge gap involves the subset of patients with neither preserved nor frankly reduced LVEF (i.e., borderline or mildly reduced LVEF [HF-BREF]). As such, it is unclear under what circumstances and to what extent we can and should be grouping HF patients together with varying level of LVEF for risk assessment, versus considering risk uniquely in different HF patient populations.

Understanding the relative importance of common predictor variables for important clinical outcomes among different groups of left ventricular systolic function should provide needed clarity to the field of HF risk prediction. Therefore, the objective of this study was to model a common set of demographic and clinical characteristics across categories of LVEF for predicting death and hospitalization in a large, multi-center, community-based, contemporary cohort of adults with HF.

Methods

Patients

The Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN) served as the source population.13 Participating sites for the current analysis were Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, and the Fallon Community Health Plan.14 Participating sites provide care to an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse population across varying clinical practice settings and geographically diverse areas. A Virtual Data Warehouse at each site served as a distributed standardized data resource comprised of electronic datasets, populated with linked demographic, administrative, ambulatory pharmacy, outpatient laboratory test results, and health care utilization data (ambulatory visits and network and non-network hospitalizations with diagnoses and procedures) for members receiving care at participating sites.15 Institutional review boards at participating sites approved the study and waiver of consent was obtained due to the nature of the study.

We first identified all persons aged ≥21 years with diagnosed HF between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2008. Patients were included if they were hospitalized with a primary discharge diagnosis of HF and/or had ≥3 ambulatory visits with a diagnosis of HF with at least one visit being with a cardiologist during the sampling frame. We used the following International Classification of Diseases, 9thEdition (ICD-9) codes: 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, 428.x. Prior studies have shown a positive predictive value of >95% for HF based on this inpatient coding algorithm when compared against chart review and Framingham clinical criteria16-18.

Covariates

Assessments of left ventricular systolic function were ascertained for each HF patient from echocardiograms, radionuclide scintigraphy, other nuclear imaging modalities, and left ventriculography test results available from site-specific databases complemented by manual chart review. We defined 3 categories of left ventricular systolic function: preserved (HF-PEF) as a reported quantitative LVEF ≥50% or a physician's qualitative assessment of “preserved” or “normal” LVEF; borderline reduced (HF-BREF) as LVEF 41-49% or “mildly” decreased; and reduced (HF-REF) as LVEF ≤40% or “moderately” or “severely” reduced.19 If the quantitative and qualitative assessments disagreed, the summary qualitative measure was used. The measure obtained closest to but after the index date of study entry was used. Patients without a documented LVEF measurement were excluded from the cohort (N=6,998; 18.9%).

Variables included in the respective models were chosen a priori based on previously published HF prognostic models3-9 and availability within the VDW. We determined the presence of coexisting illnesses based on diagnoses or procedures using relevant ICD-9 codes, laboratory results, or filled outpatient prescriptions from health plan databases, as well as site-specific diabetes mellitus and cancer registries. We collected baseline and follow-up data on diagnoses and procedures based on previously described ICD-9 codes and CPT procedure codes.20 We ascertained available ambulatory results for blood pressure, cholesterol measurements, and hemoglobin level on or before the index hospitalization and during follow-up from health plan ambulatory visit and laboratory databases. Some potentially available factors known to correspond with risk were nonetheless excluded due to technical issues. Covariates notably missing from model construction included medication use, serum natriuretic peptide levels, and measures of renal function.

Outcomes

Deaths were identified from hospital and billing claims databases, administrative health plan databases, state death certificate registries, and Social Security Administration files as available at each site. These approaches have yielded >97% vital status information in prior studies.14, 17 Hospitalizations were determined from each site's VDW. Hospitalizations for HF were identified from each site's VDW based on a primary discharge diagnosis for HF using the same inclusion criteria ICD-9 codes described previously.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software, version 9.1 (Cary, NC). We characterized baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by LVEF categories. Continuous variables were categorized using cut points chosen based on clinically meaningful values. Missing covariate data for continuous variables were treated as a separate category. Due to large sample size, in addition to P-values we also calculated D-values from the standardized difference between means across LVEF strata to compare the magnitude of difference between groups. We considered a value of d > 0.1 to signify a meaningful difference.

We constructed multivariable extended Cox regression models for each outcome stratified by LVEF category. All variables listed in Table 1 were considered for model inclusion and those with a p-value ≤0.2 at baseline comparison for each outcome within each LVEF strata were included in the final regression model. Subjects were censored at the time they disenrolled from the health plan or reached the end of study follow-up on December 31, 2008; patients were also censored at the time of death for hospitalization models. We applied a robust sandwich estimator to account for clustering of multiple observations within the same subject and explored whether additional adjustment for clustering at the site level was necessary.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among 30,094 patients identified between 2005-2008, overall and stratified by left ventricular ejection fraction.

| Characteristic | Overall Cohort N = 30,094 | Preserved LVEF N = 14,907 | Borderline LVEF N = 4,862 | Reduced LVEF N = 10,325 | d-values Reduced v Preserved | d-values Reduced v Borderline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year; mean (SD) | 73.7 (12.4) | 75.6 (11.6) | 73.0 (12.2) | 71.2 (13.0) | ||

| Age categories, year | 0.29 | 0.09 | ||||

| Age <45 | 694 (2.3) | 212 (1.4) | 102 (2.1) | 380 (3.7) | ||

| Age 45-54 | 1823 (6.1) | 636 (4.3) | 326 (6.7) | 861 (8.3) | ||

| Age 55-64 | 4408 (14.7) | 1757 (11.8) | 778 (16.0) | 1873 (18.1) | ||

| Age 65-74 | 7496 (24.9) | 3553 (23.8) | 1277 (26.3) | 2666 (25.8) | ||

| Age 75-84 | 10,388 (34.5) | 5608 (37.6) | 1597 (32.9) | 3183 (30.8) | ||

| Age ≥85 | 5285 (17.6) | 3141 (21.1) | 782 (16.1) | 1362 (13.2) | ||

| Female gender, n (%) | 13,848 (46.0) | 8610 (57.8) | 1920 (39.5) | 3318 (32.1) | ||

| Medical History, n (%) | ||||||

| Prevalent heart failure | 18,090 (60.1) | 8695 (58.3) | 2990 (61.5) | 6405 (62.0) | 0.09 | 0.01 |

| Acute myocardial Infraction | 4172 (13.9) | 1588 (10.7) | 861 (17.7) | 1723 (16.7) | 0.31 | 0.04 |

| Unstable angina | 2129 (7.1) | 1026 (6.9) | 411 (8.5) | 692 (6.7) | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery | 1938 (6.4) | 911 (6.1) | 402 (8.3) | 625 (6.1) | 0.006 | 0.20 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 3220 (10.7) | 1294 (8.7) | 674 (13.9) | 1252 (12.1) | 0.23 | 0.09 |

| Ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack | 2422 (8.1) | 1299 (8.7) | 378 (7.8) | 745 (7.2) | 0.12 | 0.05 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6361 (21.1) | 3299 (22.1) | 1069 (22.0) | 1993 (19.3) | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Other thromboembolic event | 252 (0.8) | 126 (0.9) | 48 (1.0) | 78 (0.8) | 0.07 | 0.16 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 11,363 (37.8) | 6353 (42.6) | 1812 (37.3) | 3198 (31.0) | 0.31 | 0.17 |

| Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation | 975 (3.2) | 245 (1.6) | 180 (3.7) | 550 (5.3) | 0.74 | 0.23 |

| Mitral and/or aortic valvular disease | 7330 (24.4) | 4094 (27.5) | 1173 (24.1) | 2063 (20.0) | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 2782 (9.2) | 1417 (9.5) | 502 (10.3) | 863 (8.4) | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 705 (2.3) | 421 (2.8) | 93 (1.9) | 191 (1.9) | 0.26 | 0.02 |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy | 82 (0.3) | 16 (0.1) | 25 (0.5) | 41 (0.4) | 0.79 | 0.16 |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 1007 (3.4) | 164 (1.1) | 151 (3.1) | 692 (6.7) | 1.13 | 0.49 |

| Pacemaker | 2104 (7.0) | 974 (6.5) | 363 (7.5) | 767 (7.4) | 0.08 | 0.003 |

| Dyslipidemia | 20,229 (67.2) | 9866 (66.2) | 3427 (70.5) | 6936 (67.2) | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Hypertension | 23,613 (78.5) | 12,615 (84.6) | 3850 (79.2) | 7148 (69.2) | 0.54 | 0.32 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7219 (24.0) | 3552 (23.8) | 1208 (24.9) | 2459 (23.8) | <0.001 | 0.03 |

| Hospitalized bleeds | 2014 (6.7) | 1158 (7.8) | 319 (6.6) | 537 (5.2) | 0.26 | 0.15 |

| Diagnosed dementia | 2193 (7.3) | 1226 (8.2) | 329 (6.8) | 638 (6.2) | 0.19 | 0.06 |

| Diagnosed depression | 5526 (18.4) | 2984 (20.0) | 911 (18.7) | 1631 (15.8) | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| Chronic lung disease | 12,369 (41.1) | 6706 (45.0) | 1920 (39.5) | 3743 (36.3) | 0.22 | 0.08 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1197 (4.0) | 626 (4.2) | 182 (3.7) | 389 (3.8) | 0.07 | 0.004 |

| Mechanical fall | 1042 (3.5) | 618 (4.2) | 166 (3.4) | 258 (2.5) | 0.32 | 0.19 |

| Systemic cancer | 2234 (7.4) | 1192 (8.0) | 346 (7.1) | 696 (6.7) | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L; mean (SD) | 13.1 (1.9) | 12.8 (1.8) | 13.1 (1.9) | 13.5 (1.9) | ||

| Hemoglobin category, g/L; n (%) | 0.19 | 0.11 | ||||

| > 16.0 | 1655 (5.5) | 597 (4.0) | 261 (5.4) | 797 (7.7) | ||

| 15.0-15.9 | 2736 (9.1) | 1057 (7.1) | 462 (9.5) | 1217 (11.8) | ||

| 14.0-14.9 | 4818 (16.0) | 2146 (14.4) | 788 (16.2) | 1884 (18.3) | ||

| 13.0-13.9 | 5938 (19.7) | 3047 (20.4) | 951 (19.6) | 1940 (18.8) | ||

| 12.0-12.9 | 5367 (17.8) | 2946 (19.8) | 845 (17.4) | 1576 (15.3) | ||

| 11.0-11.9 | 3919 (13.0) | 2228 (15.0) | 648 (13.3) | 1043 (10.1) | ||

| 10.0-10.9 | 2328 (7.7) | 1374 (9.2) | 387 (8.0) | 567 (5.5) | ||

| 9.0-9.9 | 1045 (3.5) | 632 (4.2) | 154 (3.2) | 259 (2.5) | ||

| <9.0 | 427 (1.4) | 258 (1.7) | 77 (1.6) | 92 (0.9) | ||

| Missing | 1861 (6.2) | 622 (4.2) | 289 (5.9) | 950 (9.2) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg; mean (SD) | 131.1 (19.4) | 133.4 (19.9) | 131.2 (19.1) | 127.7 (18.2) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure category, mmHg; n (%) | 0.28 | 0.19 | ||||

| ≥180 | 689 (2.3) | 433 (2.9) | 109 (2.2) | 147 (1.4) | ||

| 160-179 | 1832 (6.1) | 1124 (7.5) | 291 (6.0) | 417 (4.0) | ||

| 140-159 | 5217 (17.3) | 2906 (19.5) | 866 (17.8) | 1445 (14.0) | ||

| 130-139 | 5646 (18.8) | 2943 (19.7) | 914 (18.8) | 1789 (17.3) | ||

| 121-129 | 4496 (14.9) | 2238 (15.0) | 729 (15.0) | 1529 (14.8) | ||

| 110-120 | 8275 (27.5) | 3564 (23.9) | 1363 (28.0) | 3348 (32.4) | ||

| 100-109 | 1571 (5.2) | 679 (4.6) | 235 (4.8) | 657 (6.4) | ||

| < 100 | 904 (3.0) | 345 (2.3) | 142 (2.9) | 417 (4.0) | ||

| Missing | 1464 (4.9) | 675 (4.5) | 213 (4.4) | 576 (5.6) | ||

| HDL cholesterol, g/dL; mean (SD) | 47.4 (14.7) | |||||

| HDL cholesterol category, g/dL; n (%) | 0.16 | 0.05 | ||||

| ≥60 | 4736 (15.7) | 2669 (17.9) | 691 (14.2) | 1376 (13.3) | ||

| 50-50.9 | 5153 (17.1) | 2676 (18.0) | 789 (16.2) | 1688 (16.4) | ||

| 40-49.9 | 8188 (27.2) | 4056 (27.2) | 1348 (27.7) | 2784 (27.0) | ||

| 35-39.9 | 4134 (13.7) | 1969 (13.2) | 702 (14.4) | 1463 (14.2) | ||

| <35 | 4728 (15.7) | 2105 (14.1) | 873 (18.0) | 1750 (17.0) | ||

| Missing | 3155 (10.5) | 1432 (9.6) | 459 (9.4) | 1264 (12.2) | ||

| LDL cholesterol, g/dL; mean (SD) | 96.5 (34.2) | |||||

| LDL cholesterol category, g/dL; n (%) | 0.02 | 0.03 | ||||

| ≥200 | 262 (0.9) | 108 (0.7) | 50 (1.0) | 104 (1.0) | ||

| 160-199.9 | 1011 (3.4) | 477 (3.2) | 165 (3.4) | 369 (3.6) | ||

| 130-159.9 | 2820 (9.4) | 1357 (9.1) | 462 (9.5) | 1001 (9.7) | ||

| 100-129.9 | 6442 (21.4) | 3304 (22.2) | 1011 (20.8) | 2127 (20.6) | ||

| 70-99.9 | 10,617 (35.3) | 5355 (35.9) | 1725 (35.5) | 3537 (34.3) | ||

| <70 | 5539 (18.4) | 2763 (18.5) | 956 (19.7) | 1820 (17.6) | ||

| Missing | 3403 (11.3) | 1543 (10.4) | 493 (10.1) | 1367 (13.2) | ||

| Total cholesterol, g/dL; mean (SD) | 173.4 (44.2) | 173.8 (43.2) | 172.5 (45.8) | 173.2 (44.9) | ||

| Total cholesterol category, g/dL; n (%) | 0.04 | 0.05 | ||||

| >240 | 1817 (6.0) | 876 (5.9) | 313 (6.4) | 628 (6.1) | ||

| 200-240 | 4667 (15.5) | 2367 (15.9) | 730 (15.0) | 1570 (15.2) | ||

| <200 | 20764 (69.0) | 10378 (69.6) | 3418 (70.3) | 6968 (67.5) | ||

| Missing | 2846 (9.5) | 1286 (8.6) | 401 (8.2) | 1159 (11.2) | ||

| Serum sodium, mmol/L; mean (SD) | 139.7 (3.5) | 139.6 (3.6) | 139.8 (3.7) | 139.7 (3.3) | ||

| Serum sodium category, mmol/l; n (%) | 0.15 | 0.07 | ||||

| ≥150 | 16 (0.1) | 9 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 4 (0.0) | ||

| 140-149 | 15503 (51.5) | 7854 (52.7) | 2506 (51.5) | 5143 (49.8) | ||

| 130-139 | 11299 (37.5) | 5751 (38.6) | 1796 (36.9) | 3752 (36.3) | ||

| <130 | 310 (1.0) | 195 (1.3) | 41 (0.8) | 74 (0.7) | ||

| Missing | 2966 (9.9) | 1098 (7.4) | 516 (10.6) | 1352 (13.1) |

In order to assess whether the association of a potential predictor variable differed based on LVEF category, we calculated interaction model results for HF-PEF versus HF-REF and separately for HF-BREF versus HF-REF for each of the 3 outcomes. In order to maintain simplicity for interpretation, we dichotomized categorical variables at the median value. We calculated p-values and hazard ratios associated with each interaction (e.g., gender*LVEF category) for the outcome of interest. Due to the systematic nature of the analysis thereby creating multiple comparisons, we chose to highlight only those interactions with a P-value of <0.01 (recognizing that a highly conservative Bonferroni correction for approximately 150 tests of interaction would use a P-value of 0.0003 for significance).

Results

We identified 30,094 adults with HF. Their mean age was 74 years, and 46% were women (Table 1). Overall, 49.5% of patients had HF-PEF, 16.2% had HF-BREF, and the remaining 34.3% had HF-REF. There was a high burden of co-morbidity across all LVEF categories. Median follow-up was 1.8 years (interquartile range 0.8-3.1). During follow up 8,060 (26.8%) patients died, 8,108 (26.9%) were hospitalized for HF, and 20,272 (67.4%) were hospitalized for any reason. In comparison to the study cohort, patients excluded due to absence of an LVEF measure were older (mean age 75.6 v. 73.7 years, p <0.001), more often white (78.9% v. 75.3%, p <0.001), trended towards more often female (47.3% v. 46.0%, p=0.06), had more prevalent HF (73.0% v. 60.1%, p<0.001), had less myocardial infarction (12.3 v. 13.9%), and generally had more comorbidity, including cerebrovascular disease (23.0% v. 21.1%, p<0.001), diabetes (26.2% v. 24.0%, p<0.001), dementia (10.0% v. 7.3%, p<0.001), and chronic lung disease (43.3% v. 41.1%); during follow up there was not a significant difference between death (27.8% for those without a measure of LVEF, p=0.08) but lower rates of HF hospitalization (22.6%, p<0.001) and all-cause hospitalization (63.4%, p<0.001).

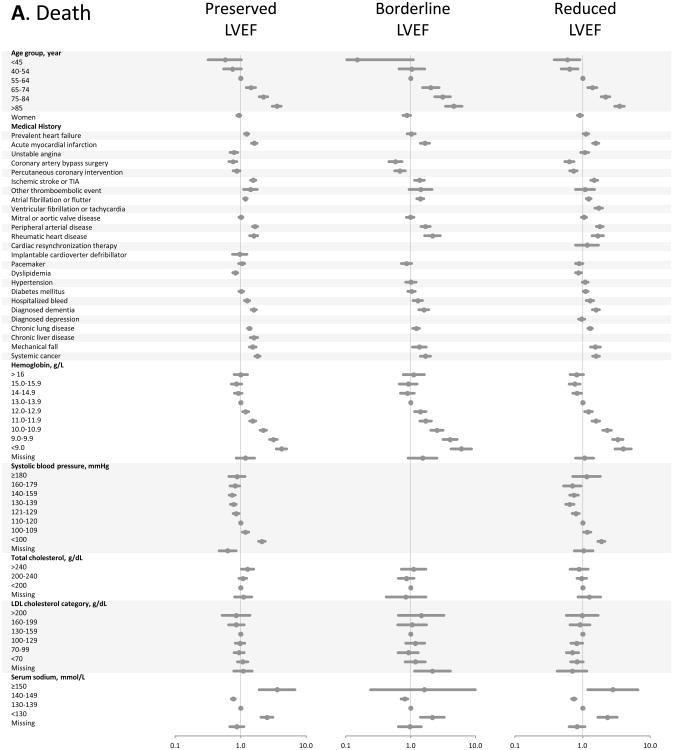

In multivariable Cox models for all-cause death (Figure, Panel A), advanced age and severe anemia showed the strongest association with the outcome across all strata of LVEF (recognizing that models did not include a measure of renal function). Only systolic blood pressures <100 mmHg showed significant association with increased mortality. Past medical history factors were either neutral or weakly associated with death, except for prior coronary revascularization which was associated with survival.

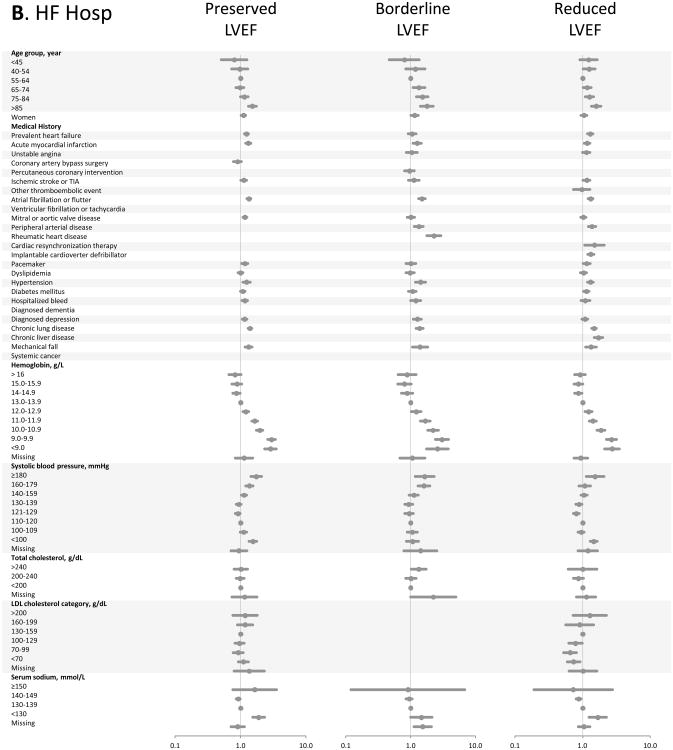

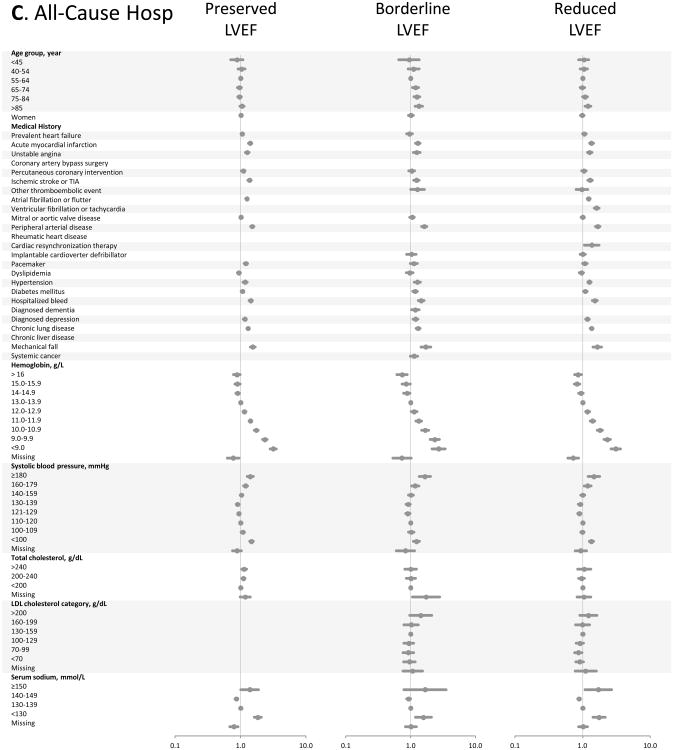

Figure.

Multivariable predictors of various clinical outcomes among 30,056 adults with heart failure and documented left ventricular systolic function assessment (2005-2008). Panel A: death from any cause across LVEF strata; Panel B: hospitalization for heart failure across LVEF strata; Panel C: hospitalization for any cause across LVEF strata. HDL included in modeling, but not shown in Forest plots; see supplemental material for full model details.

In multivariable models for hospitalization from HF (Figure, Panel B), advanced age and anemia continued to be strong predictors of the outcome across all strata of LVEF. Only patients older than age 85 years appeared to have a significantly increased risk of HF hospitalization. Hypertension, more than hypotension, was predictive of HF hospitalization. A variety of medical history carried small increased risk of HF hospitalization; notably prior coronary revascularization was not associated with hospitalization from HF.

Multivariable models for all-cause hospitalization (Figure, Panel C) were quite similar to those for HF hospitalization, despite the majority of all-cause admissions having a non-HF primary discharge diagnosis code. Anemia continued to show the largest adjusted hazards ratios for the outcome. Progressive hypertension was increasingly predictive of all-cause hospitalization; systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg was also associated with an increase in all-cause hospitalization, creating a U-shaped association for systolic blood pressure overall. Advanced age was not predictive of all-cause hospitalization, except for mild associations in the HF-BREF group and at age ≥85 years in the HF-REF group.

We found that multivariable models for each of the 3 outcomes were highly consistent across HF-PEF, HF-BREF, and HF-REF patients (Figure; complete data included as tables in the supplemental material). In simplified interaction models (Table 2), very few of the risk factors had a significant interaction with LVEF for any of the 3 outcomes (using P-value <0.01). For the outcome of all-cause mortality, only a baseline history of dyslipidemia and hypertension performed differently by HF-PEF versus HF-REF and only low-density lipoprotein differed by HF-BREF versus HF-REF. For the outcome of heart failure hospitalization, only systolic blood pressure differed by HF-PEF versus HF-REF and only age differed by HF-BREF versus HF-REF. For the outcome of all-cause hospitalization, only systolic blood pressure differed by HF-PEF versus HF-REF and only age and hemoglobin differed by HF-BREF versus HF-REF.

Table 2.

Baseline multivariable interactions between predictors and documented left ventricular systolic function assessment for death from any cause, hospitalization for heart failure, and hospitalization for any reason among 30,094 adults with heart failure (2005-2008).

| Death from Any Cause Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) Reference = Reduced LVEF | Heart Failure Hospitalization Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) Reference = Reduced LVEF | Hospitalization for Any Cause Adjusted Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) Reference = Reduced LVEF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Preserved vs. Reduced N = 14,907 | Borderline vs. Reduced N = 4,862 | Preserved vs. Reduced N = 14,907 | Borderline vs. Reduced N = 4,862 | Preserved vs. Reduced N = 14,907 | Borderline vs. Reduced N = 4,862 |

| Age group, yr | p-value=0.77 | p-value=0.10 | p-value=0.35 | p-value=0.003 | p-value=0.35 | p-value=0.003 |

| <65 | 1.10 (0.94-1.29) | 1.45 (1.16-1.80) | 1.29 (1.15-1.44) | 1.48 (1.27-1.72) | 1.29 (1.16-1.45) | 1.48 (1.27-1.72) |

| >65 | 1.13 (1.07-1.19) | 1.19 (1.11-1.28) | 1.21 (1.15-1.28) | 1.14 (1.06-1.23) | 1.22 (1.15-1.29) | 1.14 (1.06-1.23) |

| Gender | p-value=0.44 | p-value=0.65 | p-value=0.02 | p-value=0.08 | p-value=0.01 | p-value=0.05 |

| Men | 1.15 (1.07-1.23) | 1.23 (1.13-1.35) | 1.30 (1.21-1.39) | 1.26 (1.16-1.38) | 1.31 (1.22-1.40) | 1.27 (1.16-1.38) |

| Women | 1.10 (1.02-1.19) | 1.19 (1.07-1.33) | 1.15 (1.06-1.24) | 1.12 (1.01-1.24) | 1.15 (1.07-1.24) | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) |

| Prevalent heart failure | p-value=0.81 | p-value=0.05 | p-value=0.21 | p-value=0.52 | p-value=0.24 | p-value=0.58 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.11 (1.01-1.23) | 1.09 (0.95-1.24) | 1.29 (1.18-1.41) | 1.16 (1.03-1.31) | 1.29 (1.18-1.41) | 1.17 (1.04-1.32) |

| Present at baseline | 1.13 (1.06-1.20) | 1.27 (1.17-1.37) | 1.20 (1.13-1.28) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) | 1.21 (1.14-1.29) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | p-value=0.84 | p-value=0.61 | p-value=0.51 | p-value=0.85 | p-value=0.62 | p-value=0.82 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.06-1.19) | 1.21 (1.12-1.30) | 1.24 (1.17-1.31) | 1.21 (1.12-1.30) | 1.24 (1.17-1.31) | 1.21 (1.12-1.30) |

| Present at baseline | 1.14 (1.01-1.29) | 1.26 (1.08-1.47) | 1.18 (1.04-1.34) | 1.19 (1.02-1.38) | 1.20 (1.05-1.36) | 1.18 (1.02-1.38) |

| Unstable angina | p-value=0.01 | p-value=0.44 | p-value=0.11 | p-value=0.23 | p-value=0.04 | p-value=0.24 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.11 (1.05-1.17) | 1.21 (1.12-1.30) | 1.21 (1.15-1.28) | 1.19 (1.11-1.27) | 1.21 (1.15-1.28) | 1.19 (1.11-1.27) |

| Present at baseline | 1.44 (1.19-1.74) | 1.33 (1.05-1.68) | 1.41 (1.18-1.67) | 1.37 (1.10-1.70) | 1.47 (1.23-1.74) | 1.36 (1.10-1.69) |

| Coronary artery bypass | p-value=0.21 | p-value=0.04 | p-value=0.66 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 1.20 (1.11-1.28) | 1.22 (1.16-1.29) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Present at baseline | 1.29 (1.03-1.61) | 1.65 (1.23-2.22) | 1.28 (1.05-1.56) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | p-value=0.88 | p-value=0.41 | N/A | p-value=0.50 | p-value=0.89 | p-value=0.50 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.13 (1.07-1.19) | 1.21 (1.12-1.30) | N/A | 1.19 (1.11-1.28) | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1.19 (1.11-1.28) |

| Present at baseline | 1.11 (0.94-1.31) | 1.32 (1.07-1.63) | N/A | 1.28 (1.06-1.53) | 1.22 (1.05-1.42) | 1.28 (1.06-1.53) |

| Ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack | p-value=0.49 | p-value=0.44 | p-value=0.05 | p-value=0.42 | p-value=0.05 | p-value=0.38 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.13 (1.07-1.20) | 1.23 (1.14-1.32) | 1.25 (1.18-1.32) | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) | 1.25 (1.19-1.32) | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) |

| Present at baseline | 1.07 (0.92-1.24) | 1.13 (0.92-1.38) | 1.05 (0.89-1.24) | 1.11 (0.89-1.37) | 1.06 (0.90-1.24) | 1.10 (0.89-1.36) |

| Other thromboembolic event | p-value=0.84 | p-value=0.98 | p-value=0.52 | p-value=0.59 | p-value=0.53 | p-value=0.58 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.07-1.19) | 1.22 (1.14-1.31) | 1.23 (1.16-1.29) | 1.20 (1.12-1.28) | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1.20 (1.12-1.28) |

| Present at baseline | 1.18 (0.74-1.88) | 1.23 (0.67-2.25) | 1.45 (0.88-2.38) | 1.44 (0.75-2.76) | 1.45 (0.88-2.39) | 1.45 (0.75-2.77) |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | p-value=0.49 | p-value=0.91 | p-value=0.11 | p-value=0.11 | p-value=0.10 | p-value=0.11 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.11 (1.04-1.19) | 1.22 (1.12-1.34) | 1.27 (1.19-1.35) | 1.26 (1.15-1.37) | 1.27 (1.19-1.36) | 1.25 (1.15-1.36) |

| Present at baseline | 1.15 (1.06-1.24) | 1.21 (1.09-1.35) | 1.17 (1.08-1.26) | 1.12 (1.01-1.25) | 1.17 (1.08-1.27) | 1.12 (1.01-1.25) |

| Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation | p-value=0.43 | p-value=0.83 | N/A | N/A | p-value=0.96 | p-value=0.79 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 1.22 (1.13-1.30) | N/A | N/A | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1.21 (1.13-1.29) |

| Present at baseline | 1.26 (0.95-1.68) | 1.26 (0.90-1.77) | N/A | N/A | 1.24 (0.92-1.68) | 1.15 (0.83-1.59) |

| Mitral or aortic valve disease | p-value=0.60 | p-value=0.95 | p-value=0.83 | p-value=0.50 | p-value=0.84 | p-value=0.46 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.05-1.19) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) | 1.23 (1.16-1.31) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) | 1.24 (1.17-1.31) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) |

| Present at baseline | 1.15 (1.05-1.27) | 1.21 (1.07-1.38) | 1.22 (1.10-1.34) | 1.16 (1.02-1.32) | 1.22 (1.11-1.35) | 1.15 (1.01-1.31) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | p-value=0.86 | p-value=0.83 | p-value=0.57 | p-value=0.53 | p-value=0.50 | p-value=0.50 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.06-1.19) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) | 1.22 (1.16-1.29) | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) | 1.23 (1.16-1.29) | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) |

| Present at baseline | 1.14 (0.99-1.31) | 1.20 (0.99-1.44) | 1.28 (1.10-1.49) | 1.14 (0.94-1.38) | 1.30 (1.11-1.51) | 1.13 (0.93-1.37) |

| Rheumatic heart disease | p-value=0.35 | p-value=0.08 | N/A | p-value=0.05 | N/A | N/A |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 1.23 (1.15-1.32) | N/A | 1.22 (1.14-1.30) | N/A | N/A |

| Present at baseline | 1.27 (0.98-1.65) | 0.88 (0.62-1.27) | N/A | 0.78 (0.50-1.20) | N/A | N/A |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy | p-value=0.17 | p-value=0.59 | p-value=0.13 | p-value=0.26 | p-value=0.15 | p-value=0.27 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.07-1.18) | 1.22 (1.14-1.30) | 1.23 (1.16-1.29) | 1.20 (1.12-1.28) | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1.20 (1.12-1.28) |

| Present at baseline | 2.69 (0.78-9.32) | 1.54 (0.65-3.65) | 3.88 (0.89-16.90) | 2.02 (0.83-4.93) | 3.68 (0.84-16.04) | 1.98 (0.81-4.84) |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | p-value=0.19 | N/A | p-value=0.38 | p-value=0.38 | p-value=0.31 | p-value=0.39 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | N/A | 1.22 (1.16-1.29) | 1.20 (1.12-1.28) | 1.23 (1.17-1.29) | 1.20 (1.12-1.28) |

| Present at baseline | 1.42 (1.00-2.02) | N/A | 1.43 (1.01-2.04) | 1.41 (0.99-2.00) | 1.48 (1.04-2.10) | 1.40 (0.99-2.00) |

| Pacemaker | p-value=0.92 | p-value=0.53 | p-value=0.77 | p-value=0.65 | p-value=0.83 | p-value=0.62 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.07-1.19) | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) | 1.22 (1.16-1.29) | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) |

| Present at baseline | 1.13 (0.96-1.34) | 1.30 (1.04-1.63) | 1.26 (1.06-1.50) | 1.15 (0.92-1.43) | 1.26 (1.05-1.50) | 1.14 (0.92-1.42) |

| Dyslipidemia | p-value=0.005 | p-value=0.13 | p-value=0.50 | p-value=0.47 | p-value=0.44 | p-value=0.42 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.02 (0.93-1.11) | 1.12 (0.99-1.27) | 1.20 (1.09-1.31) | 1.16 (1.02-1.31) | 1.20 (1.09-1.31) | 1.15 (1.01-1.31) |

| Present at baseline | 1.18 (1.11-1.26) | 1.26 (1.16-1.37) | 1.24 (1.17-1.32) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) | 1.25 (1.17-1.33) | 1.22 (1.13-1.32) |

| Hypertension | p-value <0.001 | p-value=0.66 | p-value=0.99 | p-value=0.67 | p-value=0.95 | p-value=0.67 |

| Not present at baseline | 0.92 (0.83-1.03) | 1.18 (1.00-1.38) | 1.23 (1.09-1.38) | 1.24 (1.06-1.45) | 1.23 (1.09-1.38) | 1.24 (1.06-1.45) |

| Present at baseline | 1.18 (1.12-1.25) | 1.23 (1.14-1.32) | 1.23 (1.16-1.30) | 1.20 (1.11-1.29) | 1.23 (1.17-1.31) | 1.20 (1.11-1.29) |

| Diabetes mellitus | p-value=0.22 | p-value=0.57 | p-value=0.16 | p-value=0.13 | p-value=0.19 | p-value=0.11 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.11 (1.04-1.17) | 1.20 (1.11-1.30) | 1.20 (1.13-1.28) | 1.17 (1.08-1.26) | 1.21 (1.14-1.28) | 1.17 (1.08-1.26) |

| Present at baseline | 1.18 (1.07-1.30) | 1.26 (1.10-1.43) | 1.30 (1.18-1.43) | 1.31 (1.15-1.48) | 1.30 (1.18-1.43) | 1.31 (1.16-1.49) |

| Hospitalized bleed | p-value=0.40 | p-value=0.59 | p-value=0.62 | p-value=0.87 | p-value=0.78 | p-value=0.85 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.13 (1.07-1.20) | 1.23 (1.14-1.32) | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1.21 (1.13-1.29) | 1.24 (1.17-1.30) | 1.21 (1.13-1.29) |

| Present at baseline | 1.05 (0.90-1.24) | 1.15 (0.92-1.43) | 1.18 (0.99-1.40) | 1.18 (0.94-1.49) | 1.20 (1.01-1.44) | 1.18 (0.93-1.49) |

| Diagnosed dementia | p-value=0.50 | p-value=0.67 | N/A | N/A | N/A | p-value=0.24 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | 1.22 (1.14-1.32) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.22 (1.14-1.30) |

| Present at baseline | 1.18 (1.02-1.36) | 1.17 (0.96-1.43) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.04 (0.81-1.34) |

| Diagnosed depression | p-value=0.048 | p-value=0.48 | p-value=0.81 | p-value=0.28 | p-value=0.64 | p-value=0.33 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.10 (1.04-1.16) | 1.20 (1.12-1.30) | 1.22 (1.16-1.30) | 1.23 (1.14-1.32) | 1.23 (1.16-1.30) | 1.22 (1.14-1.32) |

| Present at baseline | 1.25 (1.11-1.40) | 1.28 (1.09-1.50) | 1.24 (1.11-1.39) | 1.12 (0.97-1.30) | 1.26 (1.13-1.41) | 1.13 (0.98-1.30) |

| Chronic lung disease | p-value=0.13 | p-value=0.42 | p-value=0.54 | p-value=0.31 | p-value=0.58 | p-value=0.31 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.16 (1.09-1.25) | 1.19 (1.09-1.30) | 1.24 (1.16-1.33) | 1.17 (1.07-1.28) | 1.25 (1.17-1.33) | 1.17 (1.07-1.27) |

| Not present at baseline | 1.08 (1.00-1.16) | 1.26 (1.13-1.40) | 1.21 (1.12-1.30) | 1.25 (1.13-1.39) | 1.21 (1.13-1.31) | 1.25 (1.13-1.39) |

| Chronic liver disease | p-value=0.83 | N/A | p-value=0.84 | p-value=0.12 | N/A | N/A |

| Not present at baseline | 1.13 (1.07-1.19) | N/A | 1.23 (1.16-1.29) | 1.19 (1.11-1.27) | N/A | N/A |

| Present at baseline | 1.10 (0.87-1.39) | N/A | 1.26 (0.99-1.59) | 1.56 (1.12-2.18) | N/A | N/A |

| Mechanical fall | p-value=0.455 | p-value=0.99 | p-value=0.19 | p-value=0.21 | p-value=0.21 | p-value=0.17 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.13 (1.07-1.19) | 1.22 (1.13-1.31) | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1.21 (1.14-1.30) | 1.24 (1.18-1.31) | 1.21 (1.14-1.30) |

| Present at baseline | 1.04 (0.85-1.28) | 1.22 (0.92-1.62) | 1.04 (0.80-1.34) | 0.98 (0.71-1.36) | 1.05 (0.81-1.35) | 0.96 (0.70-1.34) |

| Systemic cancer | p-value=0.10 | p-value=0.34 | N/A | N/A | N/A | p-value=0.50 |

| Not present at baseline | 1.14 (1.08-1.21) | 1.23 (1.15-1.32) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.20 (1.12-1.28) |

| Present at baseline | 0.99 (0.85-1.16) | 1.10 (0.89-1.37) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1.30 (1.03-1.65) |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | p-value=0.04 | p-value=0.55 | p-value=0.03 | p-value=0.003 | p-value=0.04 | p-value=0.002 |

| <13.0 | 1.18 (1.10-1.26) | 1.24 (1.13-1.36) | 1.16 (1.08-1.25) | 1.09 (0.99-1.19) | 1.17 (1.08-1.26) | 1.08 (0.98-1.19) |

| >13.0 or missing | 1.07 (0.99-1.15) | 1.19 (1.08-1.32) | 1.29 (1.20-1.38) | 1.32 (1.20-1.45) | 1.29 (1.21-1.39) | 1.32 (1.21-1.45) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | p-value=0.39 | p-value=0.31 | p-value=0.003 | p-value=0.18 | p-value=0.002 | p-value=0.19 |

| ≤120 or missing | 1.15 (1.07-1.24) | 1.27 (1.14-1.40) | 1.35 (1.24-1.46) | 1.27 (1.15-1.40) | 1.35 (1.25-1.46) | 1.27 (1.15-1.40) |

| >120 | 1.10 (1.03-1.18) | 1.18 (1.07-1.29) | 1.15 (1.08-1.23) | 1.16 (1.06-1.26) | 1.16 (1.08-1.24) | 1.16 (1.06-1.26) |

| HDL cholesterol, g/dL | p-value=0.89 | p-value=0.17 | p-value=0.09 | p-value=0.86 | p-value=0.08 | p-value=0.89 |

| <40 or missing | 1.12 (1.04-1.21) | 1.16 (1.04-1.28) | 1.29 (1.19-1.40) | 1.21 (1.10-1.34) | 1.30 (1.20-1.40) | 1.21 (1.10-1.34) |

| ≥40 | 1.13 (1.06-1.21) | 1.27 (1.16-1.40) | 1.19 (1.11-1.27) | 1.20 (1.10-1.31) | 1.19 (1.11-1.27) | 1.20 (1.10-1.31) |

| LDL cholesterol, g/dL | p-value=0.998 | p-value=0.003 | p-value=0.38 | p-value=0.31 | p-value=0.37 | p-value=0.30 |

| <140 or missing | 1.13 (1.06-1.19) | 1.18 (1.09-1.26) | 1.22 (1.15-1.29) | 1.19 (1.11-1.28) | 1.22 (1.16-1.29) | 1.19 (1.11-1.27) |

| ≥140 | 1.12 (0.97-1.30) | 1.67 (1.34-2.09) | 1.30 (1.13-1.48) | 1.31 (1.10-1.57) | 1.31 (1.14-1.49) | 1.31 (1.10-1.57) |

| Total cholesterol, g/dL | p-value=0.68 | p-value=0.15 | p-value=0.73 | p-value=0.42 | p-value=0.66 | p-value=0.45 |

| <200 or missing | 1.13 (1.07-1.20) | 1.19 (1.11-1.28) | 1.22 (1.15-1.29) | 1.19 (1.10-1.28) | 1.23 (1.16-1.30) | 1.19 (1.10-1.28) |

| ≥200 | 1.10 (0.98-1.24) | 1.37 (1.15-1.62) | 1.25 (1.12-1.39) | 1.27 (1.10-1.47) | 1.26 (1.13-1.40) | 1.27 (1.09-1.46) |

| Serum sodium, mmol/l | p-value=0.52 | p-value=0.29 | p-value=0.96 | p-value=0.16 | p-value=0.96 | p-value=0.20 |

| <140 or missing | 1.11 (1.03-1.19) | 1.26 (1.15-1.39) | 1.23 (1.14-1.32) | 1.26 (1.15-1.39) | 1.23 (1.15-1.33) | 1.26 (1.14-1.38) |

| ≥140 | 1.14 (1.07-1.23) | 1.17 (1.07-1.29) | 1.23 (1.14-1.31) | 1.15 (1.05-1.26) | 1.23 (1.15-1.32) | 1.16 (1.05-1.27) |

N/A denotes a variable was not adjusted for in the model. Variables were not included if baseline comparison p-value was greater than 0.2.

Discussion

Within a large, contemporary, multicenter cohort of patients with HF, we found that commonly available risk factors carried surprisingly similar prognostic information for a variety of outcomes across all LVEF categories. Despite the existence of a variety of published HF risk models, this systematic assessment of relative risk factor performance across three LVEF strata for death, HF-related hospitalization, and all-cause hospitalization within a diverse, representative HF population provides novel HF risk information. For example, the popularized Seattle Heart Failure Model4 was derived and validated in randomized trial populations of patients with HF-REF. Its performance has subsequently been tested in a variety of other cohorts, including patients with a range of LVEF,21,22 but this piece-meal approach makes comparisons of individual risk factor performance across different LVEF categories more difficult. Others have begun to look at the comparative prognostic performance of single risk factors by LVEF categories, such as a recent analysis showing that for a given serum B-type natriuretic peptide level the prognosis is essentially the same for patients with HF-PEF as those with HF-REF.23 Here the analytic approach was specifically designed to provide information on comparative risk factor performance across a wide range of covariates by LVEF categories. We essentially found that none of the risk factors consistently interacted with LVEF.

While LVEF dictates responsiveness to certain HF therapies,24 our data demonstrate that common risk factors have quite similar prognostic performance across major strata of LVEF. The number of statistically significant differences in risk factor performance across LVEF strata in our models were not much different than would have been predicted by chance alone. We conclude that a parsimonious approach to HF risk modeling is appropriate in most circumstances, at least for discrimination among singular endpoints. This may have important practical implications for HF risk stratification efforts, particularly since LVEF has been difficult to automatically extract from most electronic medical records without manual chart review.

Our findings extend those of previous HF risk studies, particularly into the population of patients with HF-PEF and HF-BREF. Our results are consistent with several smaller studies of hospitalized patients with HF-PEF, which have observed higher risks of hospitalization in patients with diabetes, depressive symptoms, and anemia25-27.

Potential Limitations

Due to the large sample size, some associations within individual risk models may be statistically significant but not clinically meaningful. More important, even with the relative power of this sample size we found strikingly few statistically and even fewer clinically significant differences between risk models, strengthening the primary conclusion that risk factor and overall model performance was quite similar within LVEF strata. Second, insured populations in our participating health plans may not be fully representative of the general population. Nevertheless, the breadth of geographic and demographic diversity represented across 4 geographically diverse health plans, as well as the community-based nature of health care delivery, suggest that findings from our cohort are likely to be highly generalizable to HF patients with any level of LVEF in “real-world” practice settings. This is in stark contrast to previously reported studies focused on highly selected patient samples enrolled into clinical trials or referral-based tertiary care academic medical centers. Finally, model construction did not include an exhaustive list of all previously known risk factors for adverse outcomes in HF. For example, measures of renal function, natriuretic peptide levels, and medication utilization were absent from the list of independent variables. Unlike the construction of risk models for clinical use where the goal is to optimize prognostic performance, the purpose of this analysis was to compare the relative performance of a variety of predictor variables across clinically important LVEF categories for common clinical end points. While inclusion of additional predictor variables may have led to quantitative adjustments in the reported adjusted hazards ratios (e.g., degree of association of anemia in a model with and without a measure of kidney dysfunction), meaningful relative comparisons across LVEF strata and clinical outcomes should qualitatively not be contingent upon a single variable. Additionally, both natriuretic peptide levels and measures of renal function have been shown to be strongly predictive in both HFPEF and HFREF populations such that their addition to the current analysis would not be expected to disrupt the overall symmetry seen with the current list of covariates23.

Conclusion

This study systematically assessed predictor covariate performance across clinically important LVEF strata for relevant clinical outcomes. We found that in a large contemporary HF population, despite important therapeutic distinctions currently dictated by LVEF, risk assessment was strikingly similar regardless of LVEF. These data suggest that HF risk models using traditional risk markers can be applied to broad HF populations.

Clinical Summary.

Heart failure (HF) is generally associated with high morbidity and mortality, but prognosis can vary significantly between patients. A variety of risk models exist to help risk stratify patients, thereby refining patients' and families' expectations for the future, guiding decisions around aggressiveness of care, and enabling for case mix adjustment in institutional outcome measures. Although HF is a syndrome with important differences in response to therapy by left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), existing models are typically derived and validated without careful consideration of potential differences in risk factor performance by LVEF. Therefore, we systematically assessed the relative performance of risk factors across clinically important LVEF strata for the relevant clinical outcomes of death and hospitalization. We found that in a large contemporary HF population, risk assessment was strikingly similar regardless of LVEF; we identified no clinically important interactions between LVEF and a wide range of predictor variables. These data suggest that it is unlikely for LVEF-specific HF risk models to provide markedly better prognostic information than general HF risk models; a parsimonious approach of HF risk modeling using traditional risk markers derived from broad HF populations appears reasonable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all of the project managers, data programmers, and analysts for their critical technical contributions and support that made this study possible.

Sources of Funding: This study was conducted within the Cardiovascular Research Network sponsored by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (U19HL91179-01) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (NHLBI 1RC1HL099395). Dr. Allen is supported by funding from the NHLBI (1K23HL105896). Dr. Saczynski was supported in part by funding from the National Institute on Aging (K01AG33643) and the NHLBI (U01HL105268).

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB on behalf of the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2013 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hlatky MA, Greenland P, Arnett DK, Ballantyne CM, Criqui MH, Elkind MS, Go AS, Harrell FE, Jr, Hong Y, Howard BV, Howard VJ, Hsue PY, Kramer CM, McConnell JP, Normand SL, O'Donnell CJ, Smith SC, Jr, Wilson PW. Criteria for evaluation of novel markers of cardiovascular risk: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2009;119:2408–2416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: Derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA. 2003;290:2581–2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, Anand I, Maggioni A, Burton P, Sullivan MD, Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Mann DL, Packer M. The seattle heart failure model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaronson KD, Schwartz JS, Chen TM, Wong KL, Goin JE, Mancini DM. Development and prospective validation of a clinical index to predict survival in ambulatory patients referred for cardiac transplant evaluation. Circulation. 1997;95:2660–2667. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fonarow GC, Adams KF, Jr, Abraham WT, Yancy CW, Boscardin WJ. Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: Classification and regression tree analysis. JAMA. 2005;293:572–580. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Connor CM, Hasselblad V, Mehta RH, tasissa G, Califf RM, Fiuzat M, Rogers JG, Leier CV, Stevenson LW. Triage after hospitalization with advanced heart failure: The escape (evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness) risk model and discharge score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:872–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, Yusuf S, McMurray JJ, Swedberg KB, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Pieper KS, Granger CB. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. European heart journal. 2006;27:65–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komajda M, Carson PE, Hetzel S, McKelvie R, McMurray J, Ptaszynska A, Zile MR, Demets D, Massie BM. Factors associated with outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Findings from the irbesartan in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction study (i-preserve) Circulation Heart failure. 2011;4:27–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.932996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinberg BA, Zhao X, Heidenreich PA, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC. Trends in patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: Prevalence, therapies, and outcomes. Circulation. 2012;126:65–75. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.080770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, Gong Y, Liu PP. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:260–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Go AS, Magid DJ, Wells B, Sung SH, Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Greenlee RT, Langer RD, Lieu TA, Margolis KL, Masoudi FA, McNeal CJ, Murata GH, Newton KM, Novotny R, Reynolds K, Roblin DW, Smith DH, Vupputuri S, White RE, Olson J, Rumsfeld JS, Gurwitz JH. The cardiovascular research network: A new paradigm for cardiovascular quality and outcomes research. Circ Qual Care Outcomes. 2008;1:138–147. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.801654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Go AS, Yang J, Gurwitz JH, Hsu J, Lane K, Platt R. Comparative effectiveness of different beta-adrenergic antagonists on mortality among adults with heart failure in clinical practice. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168:2415–2421. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magid DJ, Gurwitz JH, Rumsfeld JS, Go AS. Creating a research data network for cardiovascular disease: The CVRN. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:1043–1045. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.8.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Go AS, Lee WY, Yang J, Lo JC, Gurwitz JH. Statin therapy and risks for death and hospitalization in chronic heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:2105–2111. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.17.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Go AS, Yang J, Ackerson LM, Lepper K, Robbins S, Massie BM, Shlipak MG. Hemoglobin level, chronic kidney disease, and the risks of death and hospitalization in adults with chronic heart failure: The anemia in chronic heart failure: Outcomes and resource utilization (anchor) study. Circulation. 2006;113:2713–2723. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.577577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: The framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendel RC, Budoff MJ, Cardella JF, Chambers CE, Dent JM, Fitzgerald DM, Hodgson JM, Klodas E, Kramer CM, Stillman AE, Tilkemeier PL, Ward RP, Weigold WG, White RD, Woodard PK. Acc/aha/acr/ase/asnc/hrs/nasci/rsna/saip/scai/scct/scmr/sir 2008 key data elements and definitions for cardiac imaging a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical data standards (writing committee to develop clinical data standards for cardiac imaging) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:91–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalogeropoulos AP, Georgiopoulou VV, Giamouzis G, Smith AL, Agha SA, Waheed S, Laskar S, Puskas J, Dunbar S, Vega D, Levy WC, Butler J. Utility of the seattle heart failure model in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorodeski EZ, Chu EC, Chow CH, Levy WC, Hsich E, Starling RC. Application of the seattle heart failure model in ambulatory patients presented to an advanced heart failure therapeutics committee. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3:706–714. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Veldhuisen DJ, Linssen GCM, Jaarsma T, van Gilst WH, Hoes AW, Tijssen JGP, Paulus WJ, Voors AA, Hillege HL. B-type natriuretic peptide and prognosis in heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1498–1506. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 focused update incorporated into the acc/aha 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines: Developed in collaboration with the international society for heart and lung transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:e391–479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felker GM, Shaw LK, Stough WG, O'Connor CM. Anemia in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function. Am Heart J. 2006;151:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marechaux S, Six-Carpentier MM, Bouabdallaoui N, Montaigne D, Bauchart JJ, Mouquet F, Auffray JL, Le Tourneau T, Asseman P, Lejemtel TH, Ennezat PV. Prognostic importance of comorbidities in heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart Vessels. 2011;26:313–320. doi: 10.1007/s00380-010-0057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song EK, Lennie TA, Moser DK. Depressive symptoms increase risk of rehospitalisation in heart failure patients with preserved systolic function. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:1871–1877. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]