Abstract

Background:

The diagnosis of pityriasis rosea (PR) is generally clinical. Previous studies usually recruited relatively small numbers of patients and control subjects, leading to low power of study results. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses cannot be readily performed, as the inclusion and exclusion criteria of these studies were not uniform. We have previously validated a set of diagnostic criteria (DC) in Chinese patients with PR.

Aim:

Our aim is to evaluate the validity and applicability of the DC of PR in Indian patients with PR.

Study Design:

Prospective unblinded pair-matched case-control study.

Materials and Methods:

The setting is a dermatology clinic in India served by one board-certified dermatologist. We recruited all 88 patients seen by us during five years diagnosed to have PR to join our study. For each study subject, we recruited the next patient who consulted us with differential diagnoses of PR as control subjects. We applied the DC of PR on all study and control subjects.

Result:

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of the DC were all 100%. Two-tailed Fisher's exact probability test result was 0.036. Φ was 1.00.

Conclusion:

The set of DC can be validly applied to Indian patients with PR.

Keywords: Exclusion criteria, human herpesvirus, inclusion criteria, infectious disease, meta-analysis, power of studies, systematic review, viral exanthem

Introduction

What was known?

1. Pityriasis rosea (PR) might incur significant impact on the quality of life of patients. It is important to accurately diagnose PR. The literature available on diagnostic criteria is inadequate.

2. Power of results can be increased by systematic reviews and meta-analyzes. However, as per the Cochrane report, it is difficult to conduct such reviews and analyzes as the diagnosis of PR is essentially clinical and non-standardized in previous studies.

3. One set of diagnostic criteria was proposed and validated in Chinese patients with PR.

Numerous recent studies in search for the etiology of pityriasis rosea (PR) did not pinpoint a definite viral,[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17] other infectious,[18] or other causes.[19] Results of these studies might not be directly comparable to each other as the clinically setting in these studies, the methods of diagnosis, the inclusion criteria, the exclusion criteria, and the investigations performed to confirm or refute the diagnosis varied to large extents.

Apart from microbiological investigations, treatment trials for PR also differed to each other for inclusion and exclusional criteria.[20] Some studies included atypical eruptions,[21] while others excluded drug-induced PR or PR-like atypical eruptions.[22] Some studies did not mention whether atypical PR and drug-related PR were included or not at all.[23]

It was commented in a Cochrane review on interventions in PR[24] that meta-analyzes for previous etiological, epidemiological, and interventional studies were impractical owing to patients with different clinical manifestations being included in various studies. A set of diagnostic criteria (DC) for PR would allow the results of future studies to be directly comparable with each other.

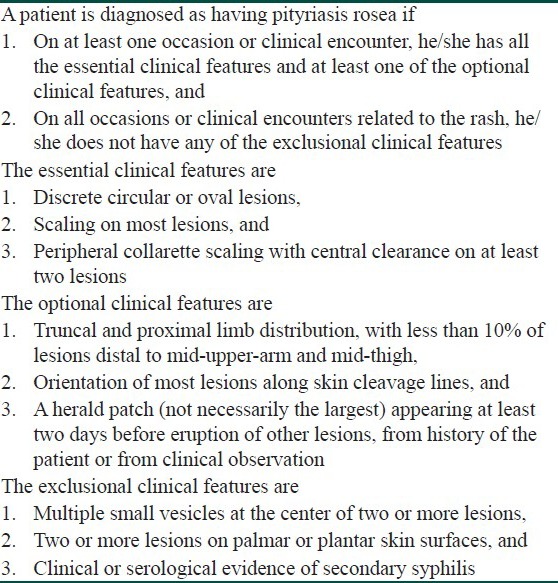

We have previously validated a set of DC [Table 1][25] for typical and atypical PR. All our patients were Chinese patients. Whether this set of DC can be applied to other populations and other ethnic groups is yet unknown. We report here a prospective case-control study to investigate the validity and feasibility of applying this DC on patients with PR in India.

Table 1.

A proposed diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea[25]

Aim

The aim of this study is to evaluate whether a set of DC for PR, previously validated only for Chinese patients with PR and differential diagnoses of PR, is valid and applicable to another ethnic group of patients with PR and differential diagnoses of PR, namely Indian patients.

Materials and Methods

Our setting was a dermatology clinic in India served by one board-certified dermatologist with experience and expertise in diagnosing and managing patients with viral and paraviral exanthems. Our time frame was 5 calendar years (1 April 2001-31 March 2006). The inclusion criteria were all patients of Indian origin having consulted the clinic on at least one occasion during the recruitment period for a skin rash, with the final diagnosis being PR. The diagnoses were made clinically by the dermatologist without referring to any DC. Patients with atypical manifestations of PR were included as long as the final diagnoses were atypical PR. Drug-induced PR or PR-like rashes were excluded. Patients with the final diagnosis being suspected PR were excluded. Whether investigations were performed on these patients did not affect inclusion or exclusion.

Once a study subject was recruited, we recruited the next patient of Indian origin who consulted the practice for skin rashes with the final diagnosis being a pre-determined set of differential diagnoses of PR (tinea corporis, secondary syphilis, guttate psoriasis, parapsoriasis, truncal pityriasis versicolor, truncal pityriasis lichenoid, nummular dermatitis mainly involving the trunk, erythema annulare centrifugum, truncal lichen planus, scabies) to be control subjects.

We obtained written content from all case subjects and control subjects. We assured all subjects that accepting or declining to join our study would not affect our clinical service for them. We took clinical photographs when such was permitted by the subjects. Whether photography was performed or not, all clinical features of all study and control subjects were carefully documented during all visits to the clinic.

We then applied the DC of PR on all study and control subjects and analyzed the results with Fisher's exact probability test and Phi coefficient of correlation (Φ). As the sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values of individual items of the DC have been previously evaluated and reported by us,[25] we evaluated the DC as a whole in this study. We employed Fisher's rather than Chi-squared as some of the entries in the contingency table to be analyzed might be less than 5. We considered two-tailed P values of less than 0.05 as being statistically significant.

Results

We identified 88 patients with PR during the recruitment period. All agreed to participate in the study. The response rate was 100%. Clear written documentations of their symptoms and signs over the entire disease period were available. The completion rate was 100%. All these patients were of Indian origin. 40 were males and 48 were females. The male/female ratio was 1:1.2. The range of age was 6 months to 54 years. The mean and median ages were 28.2 and 26.5 years, respectively.

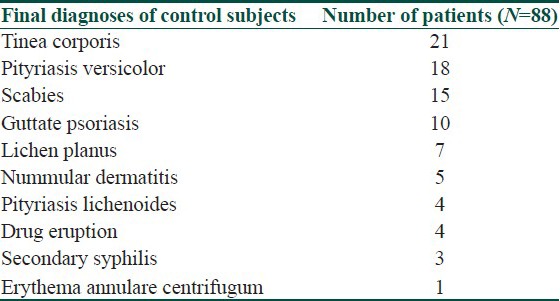

88 subjects of Indian origin who presented after individual study subjects and who were subsequently diagnosed as having differential diagnoses of PR were requested to join as control subjects. 50 were males and 38 were females. All agreed to participate. The response rate was 100%. Clear written documentations of their symptoms and signs over their disease episodes were available. The completion rate was 100%. The range of their age was 5 to 46 years. The mean and median ages for these controls were 29.1 and 26.4 years, respectively. The distribution of their final diagnoses is depicted in [Table 2].

Table 2.

The final diagnosis of 88 control subjects with a predetermined list of differential diagnoses of pityriasis rosea

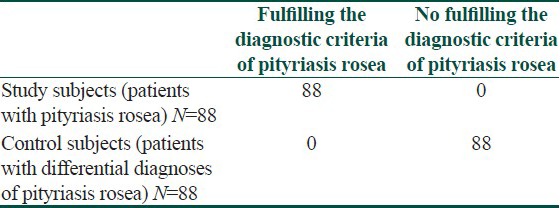

We then applied the DC to these case and control subjects. The results were depicted in [Table 3]. The sensitivity and specificity of the DC were 1.00 (95% CI: 0.97-1.00) and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.97-1.00), respectively. The positive and negative predictive values were 1.00 (95% CI: 0.97-1.00) and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.97-1.00), respectively. Fisher's exact probability test gave a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05. Φ was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.94-1.00). The number needed to diagnose was 1.00 (95% CI: 1.00-1.07).

Table 3.

Results on the application of the diagnostic criteria[25] on 88 patients with pityriasis rosea and 88 control patients

Discussion

PR frequently presents with atypical forms.[20,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] These atypical components are not all-or-nothing. We have, for example, presented case reports on patients with variable magnitudes of atypical PR rash.

For most patients with typical PR, minimally atypical PR, moderately atypical PR, and prominently atypical PR, clinical acumens of the dermatologists should be adequate to discuss with the patient on how likely or unlikely a diagnosis of PR is. As most patients with PR do not necessitate specific treatment modalities, experienced dermatologists and other clinicians might cope with the variable degrees of diagnostic uncertainty without the need of a DC in usual clinical settings. We, therefore, believe that clinical diagnoses are adequate in these settings.

However, the requirements for more definite diagnoses are entirely different in academic settings, such as epidemiological research, research on the clinical features, virological and other anti-microbial investigations, and treatment trials. Generally, the number of patients is relatively small for investigations on PR,[24,32] and thus the power of individual studies is low. The small number of patients might lead to a lower acceptance rate for reports on PR to be accepted for publication, thus leading to publication bias.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyzes can theoretically elevate the power of the results. Funnel plots and other methodologies can be employed to detect the presence and extent of publication bias. However, all these avenues are not possible unless the populations of these studies incur high homogeneity.

With clinical diagnoses alone in recruiting patients with PR in studies, different experts might put different emphases on various clinical features (such as truncal distribution of the rash and the orientation of lesions), varying disease courses (such as prodromal symptoms, presence and timings of herald patch, and time for spontaneous remission), and tolerance on atypical variants. The adoption of a universal DC in future studies will allow for systematic reviews and meta-analyzes to be conducted, which can boost up the power of the studies as well as correcting for publication bias. DC might also streamline clinical audits and surveillance of PR and other paraviral exanthems from community health perspectives.[33]

However, there exist significant limitations and disadvantages for adopting a universal DC, such as over-dependence on these DC leading to delays in investigating for other important differential diagnoses of PR including secondary syphilis, the need for validation and re-validation of the DC in view of the emergence of novel atypical variants, and difficulties for the clinicians and the patients when applications of the DC lead to marginally positive or marginally negative results.[34]

In this study, we assumed that the gold diagnostic standard were such made by a single dermatologist. This was our independent variable. We evaluated the parameters of the DC according to the ratings of the DC made by the same dermatologist. This was our dependent variable. A significant limitation was, therefore, that as the dermatologist and the patients (who could communicate with the dermatologist) were not blinded, systemic bias could not be avoided. Even in the case that we adhered 100% diagnostic confidence to the dermatologist, we could harvest high validity for the independent variable only, not the dependent variable. We had no means to evaluate such validity. Moreover, the involvement of only one dermatologist negated any efforts to evaluate and minimize intra-rater and inter-rater reliabilities.

A much more desirable approach with higher validity and reliabilities would be for several dermatologists to diagnose patients with PR and differential diagnoses of PR, followed by another group of dermatologists or clinicians having little or no knowledge of the diagnoses to apply the DC independently. Still another approach would be to train a group of medical students or non-dermatology medical residents to recognize the signs such as the orientation of the lesions, and then asking them to apply the DC on standardized clinical photographs of the patients presented in random order to the raters.

We regret that owing to constraints in resources, we had no means to establish such a setting for our study. We thus recommend further studies on this Zawar and Chuh's Diagnostic Criteria on Pityriasis Rosea, such as studies on other ethnic groups of patients, to incorporate more stringent methods in order to attain higher validity and reliabilities in their findings.

Conclusion

We conclude that within the limitations in our study settings, the set of DC for PR previously validated on Chinese patients with PR and differential diagnoses of PR, can also be validly applied to Indian patients with PR and with differential diagnoses of PR.

What is new?

The proposed set of diagnostic criteria for PR can be validly applied to Indian patients. If these criteria can be shown to be validly applicable to other ethnic and geographical groups of patients with PR, it might facilitate future studies on PR adopting such criteria, and systemic reviews and meta-analyzes can be readily performed.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Rebora AE, Drago F. A novel influenza a (H1N1) virus as a possible cause of pityriasis rose? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:991–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen JF, Chiang CP, Chen YF, Wang WM. Pityriasis rosea following influenza (H1N1) vaccination. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011;74:280–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prantsidis A, Rigopoulos D, Papatheodorou G, Menounos P, Gregoriou S, Alexiou-Mousatou I, et al. Detection of human herpesvirus 8 in the skin of patients with pityriasis rosea. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:604–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drago F, Broccolo F, Rebora A. Pityriasis rosea: An update with a critical appraisal of its possible herpesviral etiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:303–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canpolat Kirac B, Adisen E, Bozdayi G, Yucel A, Fidan I, Aksakal N, et al. The role of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus in the aetiology of pityriasis rosea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parija M, Thappa DM. Study of role of streptococcal throat infection in pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:171–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.44787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chia JK, Shitabata P, Wu J, Chia AY. Enterovirus infection as a possible cause of pityriasis rosea: Demonstration by immunochemical staining. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:942–3. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.7.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chuh AA, Chan PK, Lee A. The detection of human herpesvirus-8 DNA in plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells in adult patients with pityriasis rosea by polymerase chain reaction. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:667–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuh AA, Molinari N, Sciallis G, Harman M, Akdeniz S, Nanda A. Temporal case clustering in pityriasis rosea: A regression analysis on 1379 patients in Minnesota, Kuwait, and Diyarbakýr, Turkey. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:767–71. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.6.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broccolo F, Drago F, Careddu AM, Foglieni C, Turbino L, Cocuzza CE, et al. Additional evidence that pityriasis rosea is associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus-6 and -7. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1234–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chuh AA. The association of pityriasis rosea with cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and parvovirus B19 infections-a prospective case control study by polymerase chain reaction and serology. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe T, Kawamura T, Jacob SE, Aquilino EA, Orenstein JM, Black JB, et al. Pityriasis rosea is associated with systemic active infection with both human herpesvirus-7 and human herpesvirus-6. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:793–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drago F, Malaguti F, Ranieri E, Losi E, Rebora A. Human herpes virus-like particles in pityriasis rosea lesions: An electron microscopy study. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:359–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.290606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karabulut AA, Koçak M, Yilmaz N, Eksioglu M. Detection of human herpesvirus 7 in pityriasis rosea by nested PCR. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:563–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chuh AA, Chiu SS, Peiris JS. Human herpesvirus 6 and 7 DNA in peripheral blood leucocytes and plasma in patients with pityriasis rosea by polymerase chain reaction: A prospective case control study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:289–90. doi: 10.1080/00015550152572958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Offidani A, Pritelli E, Simonetti O, Cellini A, Giornetta L, Bossi G. Pityriasis rosea associated with herpesvirus 7 DNA. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:313–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drago F, Ranieri E, Malaguti F, Losi E, Rebora A. Human herpesvirus 7 in pityriasis rosea. Lancet. 1997;349:1367–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuh AA, Chan HH. Prospective case-control study of chlamydia, legionella and mycoplasma infections in patients with pityriasis rosea. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chuh AA. A prospective case control study of autoimmune markers in patients with pityriasis rosea. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:449–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01285_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuh A, Zawar V, Lee A. Atypical presentations of pityriasis rosea – case presentations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:120–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazaro-Medina A, Villena-Amurao C, Dy-Chua NS, Sit-Toledo MSW, Villanueva B. A clinicohistopathologic study of a randomized double-blind clinical trial using oral dexchlorpheniramine 4mg, betamethasone 500mcg and betamethasone 250mg with dexchlorpheniramine 2mg in the treatment of pityriasis rosea: A preliminary report. J Phil Dermatol Soc. 1996;5:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villarama C, Lansang P. Philippines: 2005. The efficacy of erythromycin stearate in pityriasis rosea: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (unpublished, retrieved by a Cochrane review) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu QY. The curative effect observation of Glycyrrhizin for pityriasis rosea. J Clin Dermatol. 1992;21:43. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chuh AA, Dofitas BL, Comisel GG, Reveiz L, Sharma V, Garner SE, et al. Interventions for pityriasis rosea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005068.pub2. CD005068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuh AA. Diagnostic criteria for pityriasis rosea: A prospective case control study for assessment of validity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:101–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2003.00519_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz MJ, Baudrier T, Azevedo F. Atypical pityriasis rosea in a pregnant woman: First report associating local herpes simplex virus 2 reactivation. J Dermatol. 2011;39:490–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2011.01349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zawar V. Pityriasis amiantacea-like eruptions in scalp: A novel manifestation of pityriasis rosea in a child. Int J Trichol. 2010;2:113–5. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.77524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zawar V. Unilateral pityriasis rosea in a child. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2010;4:54–6. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2010.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zawar V. Oligo-lesional eruptions rapidly following a herald plaque: Abortive pityriasis rosea. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:450–1. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zawar V, Godse K. Annular groin eruptions: Pityriasis rosea of vidal. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:195–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zawar V. Giant pityriasis rosea. Ind J Dermatol. 2010;55:192–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.62750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinha S, Sardana K, Garg VK. Coexistence of two atypical variants of pityriasis rosea: A case report and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:538–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balci DD, Hakverdi S. Vesicular pityriasis rosea: An atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chuh A, Zawar V, Sciallis G, Law M. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, pityriasis rosea, asymmetrical periflexural exanthem, unilateral mediothoracic exanthem, eruptive pseudoangiomatosis, and papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome - succinct reviews and arguments for a diagnostic criteria. Infect Dis Rep. 2012;4 doi: 10.4081/idr.2012.e12. [In Press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]