Abstract

The interaction between a functional apolipoprotein A2 gene (APOA2) variant and saturated fatty acids (SFAs) for the outcome of body mass index (BMI) is among the most widely replicated gene-nutrient interactions. Whether this interaction can be extrapolated to food-based sources of SFAs, specifically dairy foods, is unexplored. Cross-sectional analyses were performed in 2 U.S. population–based samples. We evaluated interactions between dairy foods and APOA2 −265T > C (rs5082) for BMI in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study (n = 955) and tested for replication in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study (n = 1116). Dairy products were evaluated as total dairy, higher-fat dairy (>1%), and low-fat dairy (≤1%) in servings per day, dichotomized into high and low based on each population median and also as continuous variables. We identified a statistically significant interaction between the APOA2 −265T > C variant and higher-fat dairy food intake in the Boston Puerto Ricans (P-interaction = 0.028) and replicated this relation in the GOLDN study (P-interaction = 0.001). In both groups, individuals with the previously demonstrated SFA-sensitive genotype (CC) who consumed a greater amount of higher-fat dairy foods had greater BMI (P = 0.013 in Boston Puerto Ricans; P = 0.0007 in GOLDN women) compared with those consuming less of the higher-fat dairy foods. The results expand the understanding of the metabolic influence of dairy products, an important food group for which variable relations to body weight may be in part genetically based. Moreover, these findings suggest that other strongly demonstrated gene-nutrient relations might be investigated through appropriate food-based, translatable avenues and may be relevant to dietary management of obesity.

Introduction

The dual contributions of genetics and environmental factors to obesity are well recognized, but interaction studies that explore both aspects in combination are relatively few (1–4). Replicated interaction studies of specific genetic variants and dietary exposures are even less common. One notable exception has emerged from investigation of a functional promoter variant in the gene encoding apolipoprotein A2 (APOA2), the second most abundant protein on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol particles. Although the mechanistic link of the protein to obesity is poorly understood, dietary saturated fat has been shown to modulate the APOA2 −265T > C-associated risk of obesity in 5 populations of European, Asian, and Puerto Rican origin (1–3). Whether findings from this well-replicated gene-nutrient interaction could be extrapolated to include foods that supply the nutrient (saturated fats) is unexplored.

A growing number of epidemiologic studies are examining whole foods rather than food components (e.g., macronutrients) for their association with body weight (5–7). Most gene-diet interaction studies conducted so far have examined nutrients, but a few are beginning to investigate commonly consumed foods or food groups in combination with genotypes for obesity-related traits (4, 8). The dairy food group is relatively unexplored relative to genetic variants, although the conflicting data presenting protective, detrimental, or lack of effects on adiposity and body weight (9–14) might have some basis in genetics. A rationale for investigating these conflicting data from the perspective of gene-dairy interactions is provided by the well-documented evolutionary effect of dairy foods and their role in positive selection on the human genome.

Positive natural selection refers to a process by which advantageous genetic variants become common in a population, and when these selective factors include diet, a theoretical basis for examining gene-diet interactions is created (15). Coinciding with the emergence of dairy farming (∼8000 y ago), positive selective forces shaped the human genome to provide reproductive advantages to those capable of lifelong dairy consumption (16). Evidence of positive selection is strongest at the lactase locus; however, the evolutionary benefits of dairy foods are likely to have affected growth, body composition, and body size, implicating additional loci involved in energy and nutrient metabolism. As an important source of energy and nutrients in the U.S. diet, dairy foods are a logical choice for investigation of gene–food interactions for body weight.

Dairy foods are complex with diverse constituents, including minerals, branched chain amino acids, oligosaccharides, bioactive peptides, and fatty acids (17), and daily consumption is generally recommended. Of the many constituents and nutrients in milk, saturated fatty acids (as a nutrient) have been most extensively evaluated for their modulation of genetic risk of obesity. Despite the health benefits attributed to dairy foods, they are also a major source of saturated fats in the U.S. diet (18). Genetically based differential susceptibility to the potentially detrimental health effects of saturated fats may substantiate the eventual refinement of dairy food recommendations according to genotypes. Several loci have been shown to modulate the relation between saturated fats and body weight, but, as previously noted, the APOA2 −265T > C variant is the most convincingly replicated. This extensive previous evidence for APOA2, in combination with the strong positive selection signal associated with dairy tolerance, provides a scientific rationale for investigating interactions between APOA2 and dairy foods for the outcome of body weight.

In summary, investigation of the role of gene–food interactions may simultaneously contribute to the ongoing debates about the role of specific foods and obesity risk, with potential translational effect. Dairy foods, as an energy source closely linked to positive selection, are associated with variable effects on health outcomes, which may be related to saturated fats or other components. One APOA2 variant has been well replicated for its interaction with saturated fats, but its relation to dairy foods and body weight is unexplored. Findings from the exploration of APOA2 and dairy foods may facilitate the development of more tailored and genetically informed recommendations for adult dairy food intakes. Therefore, in the current study, we first investigated dairy foods × APOA2 −265T > C interactions for BMI in a population of U.S. Puerto Ricans. Next, we tested for replication in an independent U.S. population of European ancestry to increase the evidence level of the findings.

Methods

Boston Puerto Rican health study

Study design and participants.

Participants were recruited for a prospective 2-y cohort study of men and women of Puerto Rican origin aged 45–74 y and living in the Boston, Massachusetts, metropolitan area. Participation eligibility was defined by self-reported Puerto Rican origin, Boston area residence, and the ability to answer interview questions in Spanish or English. Interviews to collect baseline demographic information, medical history, and dietary data were conducted between 2004 and 2009 by trained bilingual staff (19). The Institutional Review Board at Tufts University/New England Medical Center approved the protocol of the current study. Anthropometric data, including height and weight, were measured in duplicate, consistent with the techniques used by the National Health and Nutrition Surveys.

Population ancestry admixture in Boston Puerto Ricans.

Puerto Rican individuals are characterized by variable admixture from three ancestral groups: 1) European; 2) Taíno American Indian; and 3) West African. To reduce confounding related to the population substructure created by multiple ancestries (20, 21), we estimated admixture from 100 ancestry informative markers using principal components analysis (22). The calculated first major principle component was added to multivariable regression analysis models as a covariate.

Dietary assessment in Boston Puerto Ricans.

Dietary intake was estimated with a questionnaire that was derived from the National Cancer Institute Block FFQ. The Block FFQ was extensively modified to improve its use in Hispanic Americans (23, 24). Changes included the addition of foods commonly consumed by Hispanics, as well as extended portion sizes. Based on its greater correlation with dietary recall data, this modified FFQ more accurately estimated nutrients and energy intake in older Hispanics compared with the original Block FFQ (23). Participants reported type, frequency, and portion size of foods consumed over the past year. As established previously for this population, energy intakes of <600 or >4800 kcal/d were considered implausible, and individuals with intakes outside of this range were excluded from analysis (19). Dairy intakes in servings per day were computed by combining intakes of individual dairy foods, including milk, cheese, yogurt, and ice cream. “Low-fat dairy foods” included fat-free, skim, or low-fat (≤1%) products. “Higher-fat dairy foods” included all other dairy products not designated as low fat. “Total dairy foods” included all low-fat and higher-fat dairy products combined. Serving size for milk is defined as 1 cup (237 mL).

Genetics of lipid lowering drugs and diet network study population

Study design and participants.

Participants were recruited from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study (25) for enrollment in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) study. The GOLDN study was designed to evaluate genetic factors that modulate dietary and fenofibrate responses, and its methods have been described previously (1). Field centers were located in Minnesota and Utah, and the participants were of Northern European ancestry. The study protocol approval was obtained from the Human Studies Committee of the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Minnesota, University of Utah, and Tufts University/Tufts Medical Center. All participants provided written informed consent. Demographic, lifestyle, medical history, medication, and dietary data were collected through questionnaires. Anthropometric data, including height and weight, were measured in duplicate, and techniques were consistent with those used in the National Health and Nutrition Surveys.

Dietary assessment in GOLDN.

Dietary intakes were estimated using the Diet History Questionnaire, an FFQ developed by the National Cancer Institute (version 1.0; National Institutes of Health, Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute, 2007). Data were analyzed with the Diet*Calc Analysis Program to estimate pyramid food groups (including servings per day for total dairy foods, milk, yogurt, and cheese) and nutrient intakes (version 1.4.3; National Cancer Institute, Applied Research Program, 2005). Ice cream was included as milk servings equivalents. Dairy foods, including milk and foods derived from milk, were categorized as “low fat” (≤1%) or “higher fat” (>1%) based on response to questions such as “What kind of milk do you usually drink (use on cereal/use in coffee)?” with choices including whole milk, 2% milk, 1% milk, skim, nonfat, or 1/2% milk, soy milk, rice milk, other. Total dairy foods included low-fat and higher-fat forms combined. Individuals with implausible dietary intakes (total daily energy intake outside the range of 800–5500 kcal in men or 600–4500 kcal in women) were excluded.

Genetic analyses in both populations

We isolated DNA from peripheral blood samples using routine DNA isolation sets (Qiagen). Genotyping of the APOA2 single-nucleotide polymorphism was conducted using a Taqman assay with allele-specific probes on the ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) according to routine laboratory protocols. Standard quality-control procedures were applied. The rs5082 variant did not deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium expectations.

Statistical analyses

Interactions between genotype and dietary factors were evaluated by ANOVA techniques. In both populations, daily intakes of total dairy, higher-fat dairy foods, and low-fat dairy foods were tested as categorical and continuous variables. To construct categorical variables, intakes were classified into 2 groups according to the median intake of each population. Interactions between dairy food intakes and the APOA2 polymorphism were tested in multivariate interaction models with control for potential confounders, including age, sex, alcohol, smoking, physical activity, and diabetes status. In the Boston Puerto Ricans, control for ancestral admixture was added. In the GOLDN population, control for field center (Utah vs. Minnesota) was added. In each population, the population medians for total dairy, higher-fat dairy, and low-fat dairy foods were used as cutoffs to dichotomize these variables into high and low intakes. In the GOLDN population, we used the generalized estimating equation approach with exchangeable correlation structure implemented in the SAS GENMOD procedure to adjust for familial relationships. Interaction analyses were performed in the populations combined by sex, in men and women separately in GOLDN, and in women alone in the Boston Puerto Ricans. Dairy food intake was also evaluated as a continuous variable by computing predicted values for BMI for each participant from the adjusted regression model and plotting those predicted values against dairy food intake depending on the APOA2 genotype. For both populations, SAS (version 9.1 for Windows) was used to analyze data. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics.

Demographic, biochemical, anthropometric, and genotypic data for both populations are presented (Table 1). The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study population is 72% women.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics of Boston Puerto Rican Health Study and GOLDN populations by sex1

| Characteristics | Boston Puerto Rican women (n = 683) | Boston Puerto Rican men (n = 272) | GOLDN women (n = 582) | GOLDN men (n = 534) |

| Age, y | 57 ± 8 | 57 ± 8 | 48 ± 16 | 49 ± 16 |

| Female, n (%) | 683 (100) | 272 (0) | 582 (100) | 0 (0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.8 ± 6.9 | 29.6 ± 5.1* | 28.0 ± 6.2 | 28.6 ± 4.9 |

| Obese, n (%) | 431 (63) | 116 (43)* | 197 (34) | 174 (33) |

| Overweight or obese, n (%) | 599 (88) | 223 (82)* | 370 (64) | 420 (79)* |

| Energy intake, kcal/d | 2010 ± 862 | 2380 ± 857* | 1740 ± 641 | 2390 ± 923* |

| Total fat intake, % energy | 30.7 ± 5.1 | 32.1 ± 5.3* | 34.9 ± 6.7 | 36.2 ± 6.5* |

| Saturated fat intake, % energy | 9.3 ± 2.2 | 9.8 ± 2.4* | 11.6 ± 2.7 | 12.2 ± 2.7* |

| Total dairy foods, servings/d | 2.3 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 2.2 ± 1.7* |

| Low-fat dairy foods, servings/d | 0.42 ± 0.60 | 0.39 ± 0.60 | 0.86 ± 1.1 | 0.81 ± 1.2 |

| Higher-fat dairy foods, servings/d | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 0.81 ± 1.0 | 1.3 ± 1.5* |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 133 (19) | 85 (31)* | 44 (8) | 42 (8) |

| Current drinker, n (%) | 228 (33) | 139 (51)* | 296 (51) | 265 (50) |

| Type 2 diabetes, n (%) | 279 (41) | 110 (40) | 52 (9) | 37 (7) |

| APOA2 genotype, n (%) | ||||

| TT | 311 (46) | 132 (49) | 219 (38) | 193 (36) |

| CT | 305 (45) | 107 (39) | 271 (46) | 259 (49) |

| CC | 67 (9) | 33 (12) | 92 (16) | 82 (15) |

Data are means ± SDs or n (%) in genotyped individuals. *Different from corresponding women, P > 0.05. APOA2, apolipoprotein A2; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network.

Data for the Boston Puerto Ricans are presented by sex. Compared with Boston Puerto Rican women, the men demonstrated lower BMI (P < 0.0001), lower likelihood of obesity (P < 0.0001), lower likelihood of being overweight or obese (P = 0.03), greater energy intake (P < 0.0001), greater total fat intake (P < 0.0001), greater saturated fat intake (P = 0.0007), and greater higher-fat dairy foods (P = 0.041) and were more likely to be current smokers (P < 0.0001) and current drinkers (P < 0.0001). Data for the GOLDN population are presented by sex. Compared with GOLDN women, GOLDN men demonstrated greater likelihood of being overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25; P < 0.0001), greater total energy intake (P < 0.0001), greater total fat intake (P = 0.002), greater saturated fat intake (P < 0.0001), greater total dairy food intake (P = 0.0002), and greater intake of higher-fat dairy foods (P < 0.0001). The minor allele frequencies for the APOA2 −265T > C variant were 0.32 in the Boston Puerto Ricans and 0.39 in the GOLDN population.

Interactions between APOA2 −265T > C and dairy food intake in determining BMI in Boston Puerto Ricans.

Associations between APOA2 genotype and anthropometric, dietary, lifestyle, and biochemical traits have already been reported for both populations and were not replicated between Boston Puerto Ricans and GOLDN participants (2). Because the interaction between total saturated fat and genotype for BMI has been replicated extensively in multiple cohorts (1–3), we began by testing interactions between dairy intake and the APOA2 variant in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Based on previous publications using a recessive genetic model (1–3), we created 2 genotype groups (individuals homozygous for the major allele were combined with heterozygotes and compared with minor allele homozygotes).

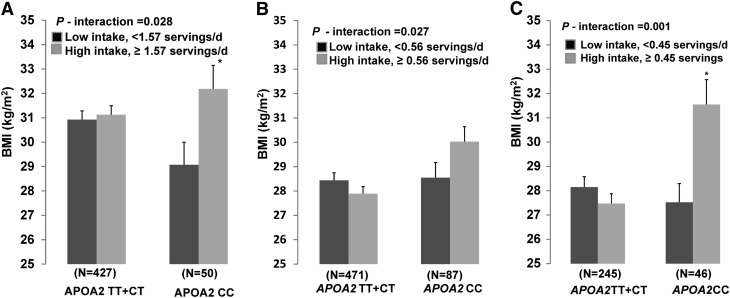

Dairy food intake (total dairy foods, higher-fat dairy foods, and low-fat dairy foods) were dichotomized based on median intake (1.9, 1.57, and 0.25 servings per day, respectively) into high and low intakes, and interactions with APOA2 genotype were tested for each type of dairy food. Interaction between total dairy intake and APOA2 genotype was not significant in the population as a whole in men or in women. For higher-fat dairy foods, a significant interaction term with genotype was obtained for the outcome of BMI (P-interaction = 0.028; Fig. 1A). For individuals with 2 copies of the minor allele (CC), those consuming greater amounts (≥1.57 servings/d) of higher-fat dairy foods had greater BMI (P = 0.013) compared with individuals with lower (<1.57 servings/d) intake of higher-fat dairy foods. BMI did not differ according to higher-fat dairy food intake in participants with 0 or 1 copy of the minor allele (TT + CT) A significant interaction term between APOA2 genotype and low-fat dairy was not obtained in the combined population or in women.

FIGURE 1.

BMI by APOA2 rs5082 genotype and intake of higher-fat dairy foods in Boston Puerto Ricans (A), in the GOLDN study (B), and in women from the GOLDN study (C). Median low and high intakes of higher-fat dairy foods are shown. Values are means ± SEMs, adjusted for age, sex, smoking and alcohol intake, physical activity, diabetes status, ancestral admixture (Boston Puerto Ricans), and family structure and field center (GOLDN study). *Different from low intake of higher-fat dairy foods, P ≤ 0.013. APOA2, apolipoprotein A2; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network.

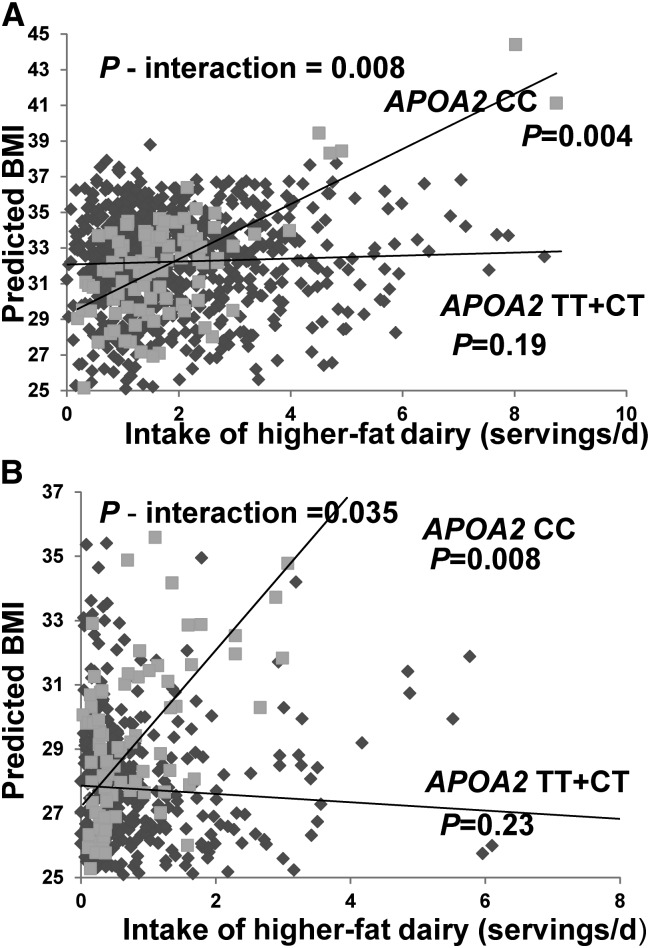

We next examined interactions between higher-fat dairy food intake as a continuous variable and APOA2 −265T > C for BMI in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Predicted values for BMI are presented as a scatter plot according to higher-fat dairy food intake for TT + CT and the CC individuals in Figure 2A. We obtained a significant interaction term between genotype and higher-fat dairy intake for predicted BMI (P-interaction = 0.008). For individuals with 2 copies of the minor allele (CC), as higher-fat dairy food intake increased, predicted BMI increased (P = 0.004). Predicted BMI did not increase with greater intake of higher-fat dairy foods in participants with 0 or 1 copy of the minor allele (TT + CT).

FIGURE 2.

Predicted BMI by APOA2 rs5082 genotype and higher-fat dairy food intake as a continuous variable in Boston Puerto Ricans (A) and GOLDN study women (B). Data were adjusted for age, sex, smoking and alcohol intake, physical activity, diabetes status, ancestral admixture (Boston Puerto Ricans), and family structure and field center (GOLDN study). APOA2, apolipoprotein A2; GOLDN, Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network.

Finally, we examined interactions between higher-fat dairy food intake and APOA2 −265T > C for BMI in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study for women, who comprise 72% of the population. The interaction term was not significant when higher-fat dairy foods were evaluated dichotomously or continuously.

Interactions between APOA2 −265T > C and dairy food intake in determining BMI in the GOLDN Study.

In the GOLDN population, we then tested for replication of the APOA2 × dairy foods interaction. As performed in the first population, we dichotomized total, higher-fat dairy foods and low-fat dairy food intakes into high and low based on the median intakes in the GOLDN population (1.59, 0.56, and 0.42 servings/d, respectively). As in the Boston Puerto Ricans, we obtained a significant interaction term (P-interaction = 0.027) for higher-fat dairy foods but not for total fat or low-fat dairy foods. Individuals with 2 copies of the minor allele (CC) who consumed greater amounts (≥0.56 servings/d) of higher-fat dairy foods tended to have greater BMI compared to individuals with low (<0.56 servings/d) intake of higher-fat dairy foods (P = 0.07), but this difference was not significant (Fig. 1B). BMI also did not differ according to higher-fat dairy food intake in individuals with 0 or 1 copy of the minor allele (TT + CT).

We next evaluated gene × diet relations separately by sex in the GOLDN population, in which the proportions of men and women are similar. We began by dichotomizing intakes into high and low based on the median intakes of total, higher-fat, and low-fat dairy foods in GOLDN women (1.48, 0.45, and 0.45 servings/d, respectively). As observed in the Boston Puerto Rican population, total dairy food intake did not interact with genotype, but higher-fat dairy food intake interacted with genotype for the outcome of BMI (P-interaction = 0.001; Fig. 1C). Women with 2 copies of the minor allele (CC) who consumed greater amounts (≥0.45 servings/d) of higher-fat dairy foods had greater BMI (P = 0.0007) compared with women with low (<0.45 servings/d) intake of higher-fat dairy foods. BMI did not differ according to higher-fat dairy food intake in individuals with 0 or 1 copy of the minor allele. We did not observe significant interactions for any dairy food intakes evaluated dichotomously (total, higher fat, low fat), in GOLDN men.

We then examined interactions between higher-fat dairy food intake as a continuous variable and APOA2 −265T > C for BMI in the GOLDN women, in which the dichotomously evaluated interaction was stronger than with both sexes combined. Consistent with the Boston Puerto Ricans, we obtained a significant interaction term (P-interaction = 0.035). Predicted values for BMI are presented as a scatter plot according to higher-fat dairy food intake for TT + CT and the CC participants in Figure 2B. For women with 2 copies of the minor allele (CC), as intake of higher-fat dairy foods increased, predicted BMI increased significantly (P = 0.008). The relation between genotype and higher-fat dairy food intake for individuals lacking 2 copies of the minor allele was not significant for BMI. Interactions between total dairy food intake evaluated continuously and the APOA2 variant in GOLDN women were not significant.

Finally, we evaluated interactions between low-fat dairy foods and APOA2 genotype in GOLDN women. In contrast to the Boston Puerto Ricans, we obtained a significant interaction term (P-interaction = 0.027; data not shown) for low-fat dairy foods evaluated as a dichotomous variable in the GOLDN women. For individuals consuming less low-fat dairy foods (<0.45 servings/d), BMI was greater (P = 0.0009) in those with 2 copies of the minor allele (30.7 ± 0.9 kg/m2) compared with those with 0 or 1 copy (27.4 ± 0.4 kg/m2). Although lower intake of low-fat dairy foods was associated with greater BMI in the CC individuals (the genotype shown previously to be SFA-sensitive) compared with TT + CT individuals, no genotype-based difference in BMI was observed when intake of low-fat dairy foods was high (data not shown). Interactions between APOA2 genotype and low-fat dairy foods evaluated continuously were not significant in GOLDN women.

We did not observe significant interactions for any dairy food intakes evaluated continuously (total, higher fat, low fat) in GOLDN men.

Correlations between higher-fat dairy foods and saturated fat intake in both populations.

We evaluated correlations between higher-fat dairy foods (servings per day) and saturated fat intake (g/d) in both populations. In the Boston Puerto Ricans, the correlation coefficient was 0.70 (P < 0.0001) and in the GOLDN study was 0.66 (P < 0.0001).

Discussion

We identified a statistically significant interaction between the APOA2 −265T > C polymorphism and dairy food intake in a U.S. Puerto Rican population, which we then replicated in an independent U.S. population of Northern European ancestry. In both populations, greater intake of higher-fat dairy foods was associated with greater BMI, only in the context of a specific APOA2 genotype. These findings represent a logical extrapolation of the most consistently replicated gene-diet interaction reported so far, may help to explain the heterogeneity in previous studies analyzing the effects of dairy food intake on obesity (9–14), and may suggest ways in which well-established findings might eventually be translated into clinical recommendations. These data are also interesting from a genomics perspective, in light of the strong positive selection signal associated with the capacity for lifelong dairy foods consumption, and suggest that additional gene-dairy analyses could be fruitful.

Previous studies of APOA2 genotype and obesity showed that saturated fat intake modulated the association of genotype with obesity, such that BMI was greater in those with the CC genotype only when intake of saturated fat was high (1). A series of subsequent human studies confirmed this gene-nutrient interaction in populations of diverse ancestry, cultures, and nationalities, including the GOLDN population and the Boston Puerto Ricans (2, 3). In addition, a single human study suggested that saturated fat intake modulates the relation between APOA2 genotype and plasma concentration of the orexigenic hormone ghrelin along with obesity-related eating behaviors (26). The current findings are conceptually similar to previous studies, in that only those individuals with genetically greater sensitivity to saturated fat intake were also more susceptible to higher body weight with greater intake of higher-fat dairy foods. These interactions were detectable with higher-fat dairy food intake evaluated continuously as well as dichotomously, lending support to a dose-response relation.

Our analysis of foods that supply saturated fat, rather than saturated fat itself, may have contributed to differences in the interactions detected in the 2 populations. In both populations, higher-fat (>1%) dairy foods interacted with APOA2 genotype for the outcome of BMI, but interaction of genotype with low-fat dairy foods was observed only in the GOLDN population. Low-fat dairy food intake has been sometimes (27) but not always (28) associated with lower risk of obesity in nongenetic studies. In GOLDN women, low intake of low-fat dairy foods was associated with greater BMI only in individuals with the saturated fat-susceptible genotype (CC). In other words, consuming greater amounts of low-fat dairy appears to reduce obesity risk in the CC individuals. The apparent protective effect of low-fat dairy foods may be related to its lower proportion of saturated fat and the potential displacement of high–saturated fat foods by foods lower in saturated fat. Alternatively, low-fat dairy products may supply other protective nutrients in relatively greater concentrations compared with higher-fat dairy. For example, the proportion of protein is slightly higher in low-fat milk compared with higher-fat milk, and dairy-based whey protein has been associated with lower subsequent energy intakes (29). Finally, our inability to detect an interaction for low-fat dairy foods in the Boston Puerto Ricans may be related to the lower consumption of low-fat dairy foods in this population, such that the exposure was insufficient for statistical detection.

Potential mechanisms to account for genetic interactions between dairy fat and the APOA2 variant can be hypothesized based on human, animal, and cell studies that have accumulated over 2 decades. Early evidence that APOA2 may both modulate and be modulated by intake behaviors began with a study of 495 Japanese individuals in whom drinking behavior modulated the relation of serum APOA2 with BMI (30). Subsequently, serum APOA2 was shown to be a biomarker for self-administered alcohol intake in monkeys (31), and APOA2 overexpression was linked to obesity in transgenic mice with ad libitum access to food (32). Evidence of a potentially mechanistic connection to saturated fat, specifically, is also provided by animal and human data. For example, saturated fat intake increased serum APOA2 in postmenopausal women (33) and increased hepatic APOA2 expression in an animal (hamster) model (34). If we consider these physiologic data in conjunction with genetic evidence, in which the APOA2 −265T > C variant was associated with lower basal transcription, as well as lower plasma APOA2 concentration in men (35), we might hypothesize that the APOA2 variant alters the response to dietary saturated fat as reflected by APOA2 concentration. In other words, exposure to dietary saturated fat may modulate APOA2 concentration differently according to APOA2 genotype, with downstream effects on intake behavior and, ultimately, BMI.

The results from the current study of dairy are not unexpected based on the strength of previous studies of APOA2 −265T > C and saturated fat, with which it shares some challenges and limitations. We cannot infer causality from these observational studies. In the current study, the populations differ genetically, culturally, and phenotypically, with a greater prevalence and severity of obesity, predominance of women, and greater prevalence of diabetes in the Boston Puerto Ricans. Although GOLDN women exhibit obesity prevalence that is similar to the overall U.S. population, obesity prevalence is greater than the U.S. average in the GOLDN men, and overweight prevalence is higher than the U.S. average in both GOLDN population and the Boston Puerto Ricans. All of these characteristics may limit generalizability to other U.S. regions, other countries, or healthier individuals. Patterns of dairy foods consumption also appear to differ between the GOLDN population and the Puerto Ricans, with a greater proportional intake of low-fat dairy foods in the GOLDN population and greater higher-fat dairy foods in the Puerto Ricans. Despite the considerable differences in these 2 U.S. groups, we observed similar interaction patterns. Although we hypothesize that the observed relations reflect an underlying interaction with dairy-based saturated fat, we cannot rule out the possibility that other dairy components, such as whey protein (29) and calcium (9, 10), may modulate the association of APOA2 genotype with BMI. In a related vein, saturated fat and dairy foods both represent markers, albeit contrasting markers, of overall dietary quality. High saturated fat intake tends to reflect a less healthy pattern, whereas dairy food intake is generally regarded as a marker for an overall healthy eating pattern, particularly in its low-fat forms. However, in both of the current populations, strong correlations (0.66 and 0.70; both P < 0.0001) between higher-fat dairy food intake and saturated fat reinforce the contribution of higher-fat dairy foods to overall saturated fats, supporting these foods as potential direct modulators of APOA2 genotype.

In summary, our study represents an extension of the most consistently replicated nutrient-gene interaction (APOA2 −265T > C × saturated fat) as a food-gene interaction (APOA2 −265T > C × dairy foods). Our results expand understanding of the metabolic influence of dairy products, an important food group that supplies unique and beneficial components but for which variable effects on adiposity may be in part genetically based. Additional studies that investigate gene × dairy interactions in a wider range of individuals, particularly outside of the United States, are warranted. Moreover, these findings support the possibility that additional, strongly demonstrated gene-nutrient relations might be investigated through appropriate food-based avenues, with potential, eventual translation into dietary recommendations.

Acknowledgments

K.L.T., D.K.A., J.M.O., D.C., and I.B.B. designed and conducted research; S.E.N., C.-Q.L.,Y.-C.L., and L.D.P. provided essential materials and data; C.E.S. and S.E.N. analyzed data; C.E.S., D.C., K.L.T., S.A., M.F.F., and J.M.O. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Literature Cited

- 1.Corella D. Arnett DK, Tsai MY, Kabagambe EK, Peacock JM, Hixson JE, Straka RJ, Province M, Lai CQ, Parnell LD, et al. The -256T>C polymorphism in the apolipoprotein A-II gene promoter is associated with body mass index and food intake in the genetics of lipid lowering drugs and diet network study. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1144–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corella D. Peloso G, Arnett DK, Demissie S, Cupples LA, Tucker K, Lai CQ, Parnell LD, Coltell O, Lee YC, et al. APOA2, dietary fat and body mass index: replication of a gene-diet interaction in three independent populations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1897–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corella D, Tai ES, Sorlí JV, Chew SK, Coltell O, Sotos-Prieto M, García-Rios A, Estruch R, Ordovas JM. Association between the APOA2 promoter polymorphism and body weight in Mediterranean and Asian populations: replication of a gene-saturated fat interaction. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:666–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qi Q, Chu AY, Kang JH, Jensen MK, Curhan GC, Pasquale LR, Ridker PM, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Rimm EB, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and genetic risk of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1387–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bes-Rastrollo M. Sabate J, Gomez-Gracia E, Alonso A, Martinez JA, Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Nut consumption and weight gain in a Mediterranean cohort: the SUN study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vang A, Singh PN, Lee JW, Haddad EH, Brinegar CH. Meats, processed meats, obesity, weight gain and occurrence of diabetes among adults: findings from Adventist Health Studies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2008;52:96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2392–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corella D, Arregui M, Coltell O, Portolés O, Guillem-Sáiz P, Carrasco P, Sorlí JV, Ortega-Azorín C, González JI, Ordovás JM. Association of the LCT-13910C>T polymorphism with obesity and its modulation by dairy products in a Mediterranean population. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19:1707–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zemel MB, Richards J, Milstead A, Campbell P. Effects of calcium and dairy on body composition and weight loss in African American adults. Obes Res. 2005;13:1218–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zemel MB, Richards J, Mathis S, Milstead A, Gebhardt L, Silva E. Dairy augmentation of total and central fat loss in obese subjects. Int J Obes (Lond). 2005;29:391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajpathak SN, Rimm EB, Rosner B, Willett WC, Hu FB. Calcium and dairy intakes in relation to long-term weight gain in US men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:559–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snijder MB, van der Heijden AA, van Dam RM, Stehouwer CD, Hiddink GJ, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, Dekker JM. Is higher dairy consumption associated with lower body weight and fewer metabolic disturbances? The Hoorn Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:989–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abargouei AS, Janghorbani M, Salehi-Marzijarani M, Esmaillzadeh A. Effect of dairy consumption on weight and body composition in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36:1485–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen M, Pan A, Malik VS, Hu FB. Effects of dairy intake on body weight and fat: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:735–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parnell LD, Lee YC, Lai CQ. Adaptive genetic variation and heart disease risk. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:116–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bersaglieri T, Sabeti PC, Patterson N, Vanderploeg T, Schaffner SF, Drake JA, Rhodes M, Reich DE, Hirschhorn JN. Genetic signatures of strong recent positive selection at the lactase gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:1111–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haug A, Hostmark AT, Harstad OM. Bovine milk in human nutrition—a review. Lipids Health Dis. 2007;6:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute 2010. Sources of saturated fat, stearic acid, & cholesterol raising fat among the US population, 2005–06. Risk factor monitoring and methods branch web site. Applied Research Program. National Cancer Institute [updated 2010 Dec 21; accessed 2013 Feb 9]. Available from: http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/diet/foodsources/sat_fat/.

- 19.Tucker KL, Mattei J, Noel SE, Collado BM, Mendez J, Nelson J, Griffith J, Ordovas JM, Falcon LM. The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort study on health disparities in Puerto Rican adults: challenges and opportunities. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cardon LR, Palmer LJ. Population stratification and spurious allelic association. Lancet. 2003;361:598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marchini J, Cardon LR, Phillips MS, Donnelly P. The effects of human population structure on large genetic association studies. Nat Genet. 2004;36:512–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai CQ, Tucker KL, Choudhry S, Parnell LD, Mattei J, Garcia-Bailo B, Beckman K, Burchard EG, Ordovas JM. Population admixture associated with disease prevalence in the Boston Puerto Rican health study. Hum Genet. 2009;125:199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker KL, Bianchi L, Maras J, Bermudez O. Adaptation of a food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of Puerto Rican and non-Hispanic adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:507–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin H, Bermudez OI, Tucker KL. Dietary patterns of Hispanic elders are associated with acculturation and obesity. J Nutr. 2003;133:3651–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins M, Province M, Heiss G, Eckfeldt J, Ellison RC, Folsom AR, Rao DC, Sprafka JM, Williams R. NHLBI Family Heart Study: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:1219–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith CE, Ordovas JM, Sanchez-Moreno C, Lee YC, Garaulet M. Apolipoprotein A-II polymorphism: relationships to behavioural and hormonal mediators of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36:130–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poddar KH, Hosig KW, Nickols-Richardson SM, Anderson ES, Herbert WG, Duncan SE. Low-fat dairy intake and body weight and composition changes in college students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hendrie GA, Golley RK. Changing from regular-fat to low-fat dairy foods reduces saturated fat intake but not energy intake in 4–13-y-old children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:1117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Astbury NM, Stevenson EJ, Morris P, Taylor MA, Macdonald IA. Dose-response effect of a whey protein preload on within-day energy intake in lean subjects. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1858–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosokai H, Tamura S, Koyama H, Satoh H. Drinking habits influence the relationship between apolipoprotein AII and body mass index. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 1993;39:235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freeman WM, Gooch RS, Lull ME, Worst TJ, Walker SJ, Xu AS, Green H, Pierre PJ, Grant KA, Vrana KE. Apo-AII is an elevated biomarker of chronic non-human primate ethanol self-administration. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castellani LW, Gargalovic P, Febbraio M, Charugundla S, Jien ML, Lusis AJ. Mechanisms mediating insulin resistance in transgenic mice overexpressing mouse apolipoprotein A-II. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:2377–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez-Muniz FJ, Merinero MC, Rodríguez-Gil S, Ordovas JM, Ródenas S, Cuesta C. Dietary fat saturation affects apolipoprotein A-II levels and HDL composition in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2002;132:50–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahn YS, Smith D, Osada J, Li Z, Schaefer EJ, Ordovas JM. Dietary fat saturation affects apolipoprotein gene expression and high density lipoprotein size distribution in golden syrian hamsters. J Nutr. 1994;124:2147–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van ’t Hooft FM, Ruotolo G, Boquist S, de Faire U, Eggertsen G, Hamsten A. Human evidence that the apolipoprotein A-II gene is implicated in visceral fat accumulation and metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Circulation. 2001;104:1223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]