Abstract

Background

Microsomal (m) prostaglandin (PG) E2 synthase (S)-1 catalyzes the formation of PGE2 from PGH2, a cyclooxygenase (COX) product that is derived from arachidonic acid. Previous studies in mice suggest that targeting mPGES-1 may be less likely to cause hypertension or thrombosis than COX-2 selective inhibition or deletion in vivo. Indeed, deletion of mPGES-1 retards atherogenesis and angiotensin II-induced aortic aneurysm formation. The role of mPGES-1 in the response to vascular injury is unknown.

Methods and Results

Mice were subjected to wire injury of the femoral artery. Both neointimal area and vascular stenosis were reduced significantly four weeks after injury in mPGES-1 knock out (KO) mice compared to wild type (WT) controls (65.6±5.7 vs 37.7±5.1×103 pixel area and 70.5±13.4% vs 47.7±17.4%, respectively; p < 0.01). Induction of tenascin C (TN-C) after injury, a pro-proliferative and promigratory extracellular matrix protein, was attenuated in the KOs. Consistent with in vivo rediversion of PG biosynthesis, mPGES-1 deleted vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) generated less PGE2, but more PGI2 and expressed reduced TN-C when compared with WT cells. Both suppression of PGE2 and augmentation of PGI2 attenuate TN-C expression, VSMC proliferation and migration in vitro.

Conclusions

Deletion of mPGES-1 in mice attenuates neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury, in part by regulating TN-C expression. This raises for consideration the therapeutic potential of mPGES-1 inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for percutaneous coronary intervention.

Keywords: Injury, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, prostacyclin, prostaglandins, vascular response

Arachidonic acid is metabolized by cyclooxygenases (COXs) to an endoperoxide intermediate, prostaglandin (PG) H2, which is subsequently converted by terminal isomerases to specific PGs. Traditional non-steroidal antinflammatory drugs (tNSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, relieve pain and fever by inhibiting COXs 1 and 2. Some tNSAIDs, such as diclofenac and meloxicam, are selective inhibitors of COX-2. Purposefully designed (pd)NSAIDs selective for inhibition of COX-2, such as celecoxib, predispose patients to myocardial infarction and stroke 1–3. Diverse lines of evidence indicate that this is attributable to suppression of COX-2-derived prostacyclin (PGI2) 4.

Microsomal (m) PGE synthase (S)-1, which catalyzes the isomerization of PGH2, into PGE2, has emerged as an alternative drug target to COX-2 5–7. Two other PGE synthases have also been identified, mPGES-2 8 and cytosolic PGES 9, 10. mPGES-1, however, is the dominant source of PGE2 biosynthesis, at least under basal conditions and in inflammatory syndromes in mice 11. Targeting of mPGES-1 may be less likely cause hypertension or thrombosis than COX-2 selective inhibitors in vivo 11, 12. While this distinction may not be absolute 13, deletion of mPGES-1 also retards atherogenesis 14 and attenuates angiotensin II induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation in LDLR−/− mice 15,

COXs and PGs differentially modulate the response to vascular injury. For example, wire induced vascular proliferation is enhanced in mice that are genetically deficient in the PGI2 receptor (IP), while deletion of the TxA2 receptor (TP) depresses this response 16. Despite the association of pdCOX-2 inhibitors with a cardiovascular hazard, there are conflicting reports of the impact of disrupting this pathway on vascular remodeling. For example, pharmacological suppression of COX-2 derived PGI2 promotes adverse vascular remodeling in a flow-induced injury model, an effect replicated by deletion of the IP17. However, celecoxib, with presumed inhibition of the same pathway, reduces neointimal hyperplasia in balloon-injured carotid arteries in rats and rabbits18, 19. Furthermore, a small controlled clinical trial suggests that celecoxib reduces in-stent late luminal loss at 6 months in patients with coronary artery disease who are receiving aspirin plus clopidogrel 20. While Wu et al21 found that celecoxib, but not mPGES-1 deletion increased mortality in mice after experimental myocardial infarction, Degousse et al observed delayed adverse ventricular remodeling in mPGES-1 knockouts22.

Tenascin-C (TN-C) is a multifunctional extracellular matrix (ECM) glycoprotein that regulates cell differentiation 23, proliferation 24, 25, survival 26 and migration 27 during development and tissue remodeling. TN-C is highly expressed during the embryonic branching morphogenesis and dissipated in the adult lungs28. TN-C is re-expressed during wound healing and regenerationas well as under the pathological conditions. In the latter setting, TN-C promotes pulmonary 29 and systemic 30, 31 vascular neointimal hyperplasia by promoting VSMC growth. In the case of pulmonary hypertension, TN-C regulates VSMC growth in part by inducing integrin associated EGF-R activation followed by regulation of downstream cell survival24 . A role for PGs in regulation of TN-C expression is suggested by earlier studies. Inhaled iloprost, a prostacyclin analog, reverses TN-C expression and vascular remodeling in experimental pulmonary hypertension in rats 32. PGE2 induces expression of TN-C in stromal cells of the murine uterus 33. Matix metalloproteinases (MMPs) upregulate TN-C by generating β3 integrin ligands in type I collagen 26 , while mPGES-1 promotes vascular MMP2 activity in a vascular inflammatory condition - aortic aneurysm15.

Here, we demonstrate that deletion of mPGES-1 in mice attenuates neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury. Both suppression of PGE2 and rediversion of the accumulated PGH2 substrate to PGI2 may contribute to impaired VSMC proliferation, dysregulated expression of TN-C expression and impaired VSMC migration in the KOs. These studies indicate a potential utility of targeting mPGES-1 in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods

Mice and the vascular injury model

mPGES-1 knockout (KO) and their wild type (WT) controls were generated by corresponding homozygous breeders derived from mPGES-1+/− mice, which are backcrossed to C57B6 for 7 generations from the original mPGES-1−/− mice which were a kind gift from Pfizer 6. The femoral artery wire injury was performed as previously described 34 with modifications. Briefly, one-side of the femoral artery was exposed by blunt dissection while mice were under anaesthesia. The accompanying femoral nerve and femoral vein were carefully separated from the artery. The femoral artery was looped proximally and distally with 6-0 silk suture for temporary blood flow cessation during the procedure. A small branch between the rectus femoris and vastus medialis muscles was isolated, a transverse arteriotomy was performed in the branch and a flexible angioplasty wire (0.35 mm diameter; Cook Inc., IN) was inserted into the femoral artery for more than 5 mm toward the iliac artery. The wire was left in place for 3 min to denude and dilate the artery. Then, the wire was removed and the silk suture looped at the proximal portion of the muscular branch artery was secured. Blood flow in the femoral artery was restored by releasing the sutures and the skin incision was closed with a 5-0 silk suture. The femoral artery on the other side was sham-operated and served as a control. Alzet osmotic minipumps (Model 2002, Alza Scientific Products, CA) were placed subcutaneously via a midback incision and loaded with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to deliver 25 mg per kg per day. Twenty-eight days after injury, animals were euthanized and perfused with 0.9% NaCl followed by Prefer (Anatech, Battle Creek, Mich). Femoral arteries were harvested and were embedded in paraffin for morphometric or histological analysis. All animals were housed according to guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Pennsylvania, and all experiments were approved by the IACUC.

Biochemical, molecular and cellular methods

PGs, or metabolites were determined using UPLC-tandem mass spectrometry as previously described 15, 35. The UPLC column used was a Hypersil GOLD, 200 mm × 2.1 mm, with a particle size of 1.9 µ (Thermo Scientific), which allows distinction of the authentic peak of 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α(PGI-M) from a endogenous peak of unknown identity at the specified ion transition. VSMCs were isolated from the aortae of WT, mPGES-1 or IP KO mice 16, as previously described 14, and only VSMCs below passage 5 were used. For RNA interference (RNAi) studies, VSMCs were trypsinized and re-seeded (7.5 × 105 cells per 100-mm dish) in media without antibiotics overnight. The next day, Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; 1 ul per 25,000 cells) and Tenascin-C(TN-C) siRNA (Ambion ID s75240; 100 nM) or control siRNA (ID: D-00121002, Dharmacon Inc., Lafayette, CO.) were diluted in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and added to the cells for 4 h before switching the cells to fresh serum-containing media overnight 36. VSMCs (70–80% confluent) were then seeded onto 35-mm diameter dishes containing autoclaved glass cover slips, after attachment they were serum starved for 48 h and then stimulated with 2% FBS for 48 h in the presence or absence of PGE2 or an IP agonist or IP antagonist before analyzing for BrdU incorporation. BrdU incorporation was determined as described previously37. Migration studies and TN-C staining was carried out 60 hours after siRNA transfection with over-night serum starvation.

Morphometry and histology

Cross-sections of the injured arteries of individual animals were serially obtained at 10 levels from the distal branch point of the femoral artery at 140 µm intervals (eight levels were sectioned for assessment of early cell infiltration/migration) and were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Images were acquired using a CCD camera coupled to an inverted Nikon E600 microscope. Images were then digitized using Image Pro software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). Morphometric analysis was performed using a customized program (Phase 3 Imaging Systems, Glen Mills, PA) of Image Pro to measure the area of the lumen, the area inside the internal elastic lamina, and the area inside the external elastic lamina. This system was also used to count BrdU-labeled cells within the media and intima of vessels. Percentage stenosis was calculated as the ratio of the intimal area to the area inside the original internal elastic lamina and the ratio of intima to media calculated. Sections with the maximal lesion area were selected to represent the animal from which femoral arteries had been harvested. Histology staining is detailed in the online supplemental material.

Measurements of cell motility

Cell motility was studied by post hoc analysis of movies that record cell behavior after seeding onto thin film of fibrillar type I collagen, prepared as described previously 38. Neutralized collagen solutions were applied to flat-bottom, non-tissue cultured treated polystyrene plates (BD Biosiences, San Jose, CA, USA), and then placed at 37°C overnight to initiate fibrillogenesis. After incubation, the gelled collagen film (monolayer) was rinsed with PBS (~10 times) and deionized water (~10 times). Samples were then dried under a stream of filtered N2 and immediately placed back into a PBS solution. Such prepared collagen films have increased rigidity which can cause cells to assume a proliferative phenotype, mimicking an injured state in vivo39. Twenty-four hours prior to the experiments, cells were treated with complete medium containing 2% Fetal Bovine Serum. Prior to seeding, cells were trypsinized with 0.25% trypsin- ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (Gibco BRL, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), and seeded in 0.5 mL of 2% FBS-Medium at a density of 2×104 cells/well (~5000 cells/cm2). Recording of cell motility was started 10 min after seeding to allow the setting of the microscope. Three or four fields of view (movies) were recorded for SMC from each animal and two animals of each genotype were used.

The live cell culture imaging system consists of a custom made biochamber with humidified atmosphere at 37°C with 5% CO2 incorporating a digitalized controlled x-y-z motorized stage driven by a stepper motor drive systems mounted on an inverted microscope (Nikon TE 2000-U, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were acquired using a high-resolution cooled CCD camera (Photometrics Ropert Scientific, Tucson, AZ) at 5 min intervals over 24 hours using a 10X phase-contrast objective lens. Image sequences were processed using Nikon Elements Software (version 3.0 Nikon), and were then converted to an 8-bit image and enhanced for contrast and brightness using Image J software (version 1.38×, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA). The percentage of spreading cells at a given time point after cell seeding was calculated from the movies. Five cells per movie were randomly chosen for velocity calculation with the only criteria being that cells should be within an observation frame from recording start till the end. The center point of the selected cells, i.e., the average of the x and y coordinates of all of the pixels in the image or selection was used to calculate the position of the cells at each time point. Distance traveled between each current time point and the immediate past time point was used to calculate the velocity at an individual time point.

Cell motility was also studied by both a scratch wound healing assay and a transwell assay. VSMCs were plated for 24 h in complete media and were then serum starved overnight before scratching the monolayer with a pipette tip for the scratch wound healing assay. Cell motility was recorded as described above every 30 min for 24 h, and serial images were converted to TIFF and MPEG movie formats for analysis. The distance cell traveled between the time when surface was scratched and 24 hours after was measured (n=5 cells per field, repeated 3 times per experiment setting). The transwell assay was used to examine effects of supplementing exogenous TN-C on SMC migration. Transwell plates (8um pore size, Corning Inc., Corning, NY) were coated with 50µl PBS-reconstituted 20µg/ml TN-C (Millipore Corporation, Temecula, CA) on both sides, at 37°C for 1 hour. Serum-starved SMCs were seeded to the upper chamber at 10,000/well, in media with 2% serum. Twenty-four hours later, cells were fixed with Prefer for 5min, and non-migrated cells on the upper well side of the membrane were gently wiped off with a cotton stick, the membrane was removed and stained with DAPI and the migrated cells were counted with high-power magnification (20X) for ten fields using a fluorescent microscope. The average cell number of the ten fields was used to represent an individual transwell reading.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM unless indicated otherwise. Comparisons of multiple groups were performed by ANOVA, and when only two mean values were compared, the two-tailed t-test was used. Bonferroni correction or Dunnett’s test was applied where appropriate as indicated in the text. In all cases, statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Deletion of mPGES-1 reduces neointimal hyperplasia in the wire-injured femoral artery

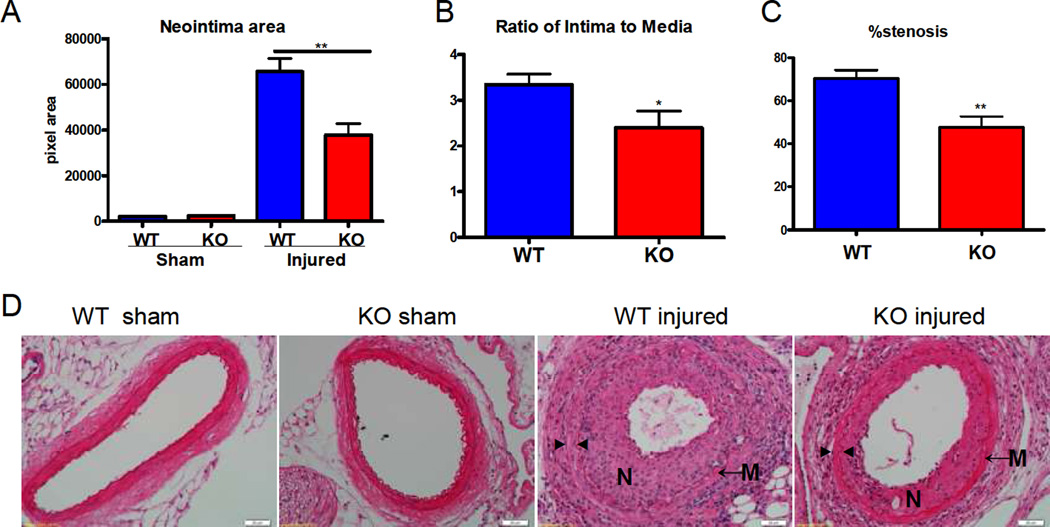

To examine the role of mPGES-1 in vascular remodeling, mice were subject to endothelial denudation by wire injury to the femoral artery and were examined 28 days later. Injured vessels from mPGES-1-deficient mice show reduced neointimal formation, a reduced intima-media ratio, and less stenosis (Figure 1 A–D). Furthermore, the percentage of proliferating cells detected following BrdU incorporation, was also reduced in the KOs (102 ± 17 vs 50 ± 12 cells/cross section). mPGES-1 was expressed in medial VSMCs, as well as in the endothelium and perivascular region within the injured vessel in WT mice (Supplemental Figure 1). Cellular infiltration/migration to subendothelium was also limited by mPGES-1 deletion 7 days following the injury (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1. Deletion of mPGES-1 reduced neointimal formation.

Neointimal area (A), the ratio of intima to media (B) and stenosis (C) were reduced significantly in mPGES-1 KO mice compared to WT controls. (*: p<0.05; **: p < 0.01. n=4 per group for sham-operated animals; n=13 for WT injured animals; n=12 for KO injured animals). Representative H&E staining of cross sections from sham operated or wire-injured arteries is shown (D). N denotes neointima; M denotes media; ► indicates internal elastin; ◄ indicates external elastin. Scale bar denotes 20 µm.

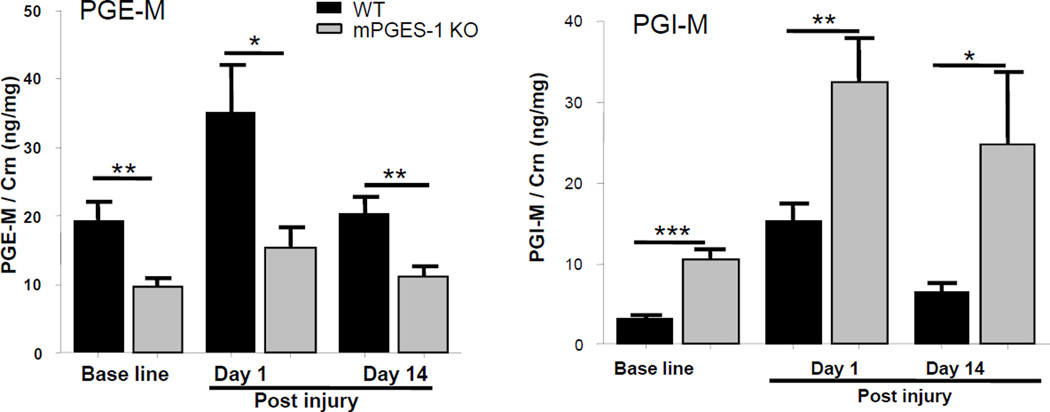

Vascular injury resulted in a procedure related increase in PG biosynthesis. Deletion of mPGES-1 significantly reduced synthesis of PGE2, while augmenting the endoperoxide rediversion products, PGI2 and PGD2. This contrast in product formation was even more pronounced when WT and KO mice were subject to injury. In that setting, formation of thromboxane (Tx) was also augmented in the KOs (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2. Depression of PGE2 and shift to augment PGI2 during vascular remodeling in mPGES-1 KO mice.

Urinary metabolites of PGE2 (A) and PGI2 (B), PGE-M and dinor-6-keto PGF1α, respectively, were compared between genotypes at baseline, day 1 and day 14 post injury. (t-test with Bonferroni correction. *: p<0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001. n=14–16 per group)

mPGES-1 deletion modulates TN-C expression and VSMC migration

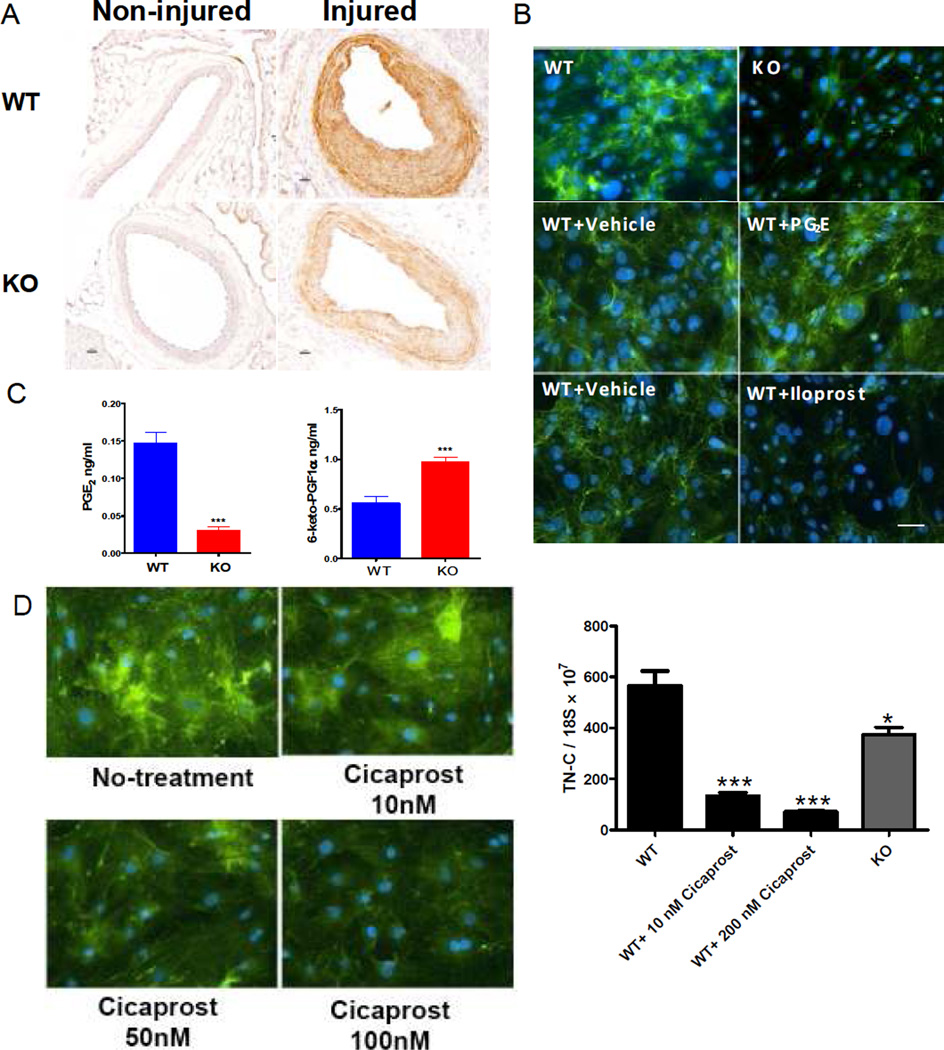

Expression of TN-C was upregulated in medial and neointimal VSMC layers in response to injury and this response was attenuated by mPGES-1 deletion (Figure 3A). Consistent with these in vivo studies, mPGES-1 deletion also reduced TN-C expression in cultured VSMCs (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. mPGES-1 modulates TN-C expression.

A: Reduced TN-C expression in injured vessel of mPGES-1 KOs. TN-C was stained in WT (upper panel) or KO (lower panel) non-injured (left column) and injured vessels (right column), as labeled in the panel. Scale bar denotes 20 µm. B: TN-C expression in cultured VSMCs. TN-C was stained as green and nuclei as blue by DAPI. TN-C expression was suppressed in mPGES-1KO VSMCs compared to WT VSMCs (upper panel). While PGE2 treatment only slightly increased expression of TN-C in WT VSMCs (middle panel), Iloprost reduced TN-C expression (lower panel), with both drugs applied at 280 nM. Bar = 20µm. C: Levels of PGE2 and 6-keto-PGF1α (the PGI2 hydrolysis product) in cultured VSMCs. (**: p < 0.01. n=6 per group). D: Expression of TN-C in SMCs treated with Cicaprost (PGI2 analogue) at indicated concentration, as reflected by immuno-fluorescence (left panel) and quantitative RT-PCR (right panel). KO SMCs produced less TN-C than WT SMCs. *: p<0.05; **: p<0.01; ***: p<0.001, n=4. All comparison is relative to WT group. Data presented are representative of three independent experiments.

Formation of the two most abundant prostanoids formed by VSMCs, PGE2 and PGI2, was differentially regulated by mPGES-1 deletion in vivo and a similar divergent pattern of formation was observed in VSMCs cultured ex vivo (Figure 3C). Here, we failed to detect production of PGD2 by VSMCs and the trivial amounts of Tx formation were unaltered by gene deletion (and data not shown). Treating WT VSMCs with PGE2 at 28 or 280 nM slightly increased TN-C expression. In contrast, the IP agonist, iloprost40 strikingly decreased TN-C expression at the same concentrations (Figure 3B and data not shown). Cicaprost11, another IP agonist also dose-dependently suppressed TN-C expression (Figure 3D). Thus, the increased levels of PGI2 may substantially contribute to the suppression of TN-C in mPGES-1 KO SMCs.

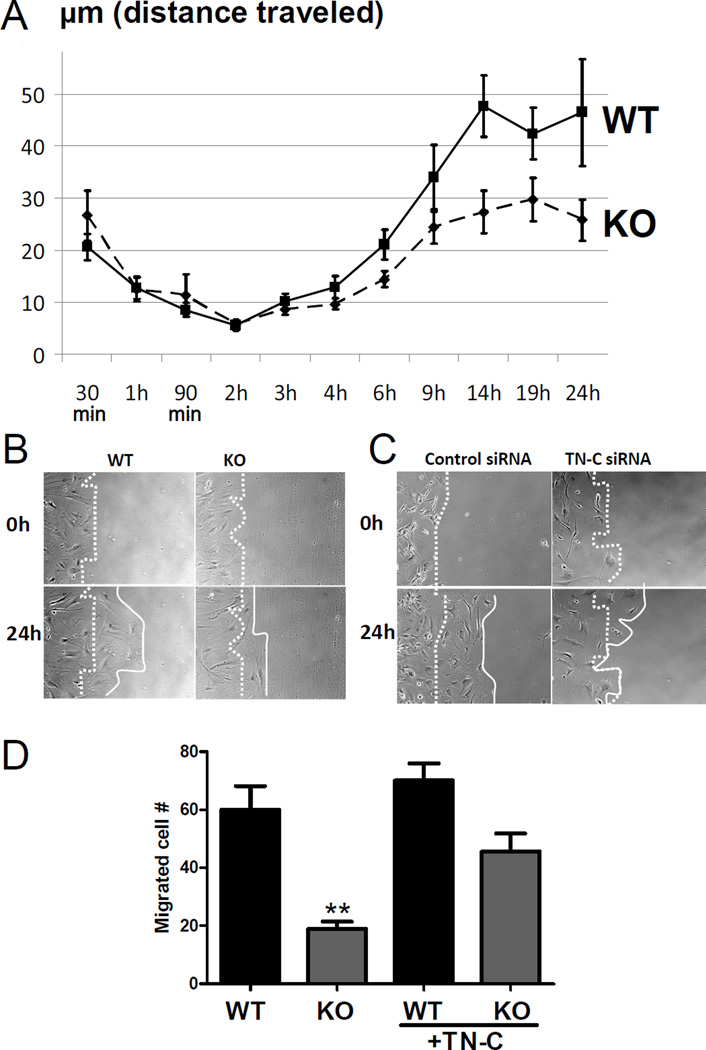

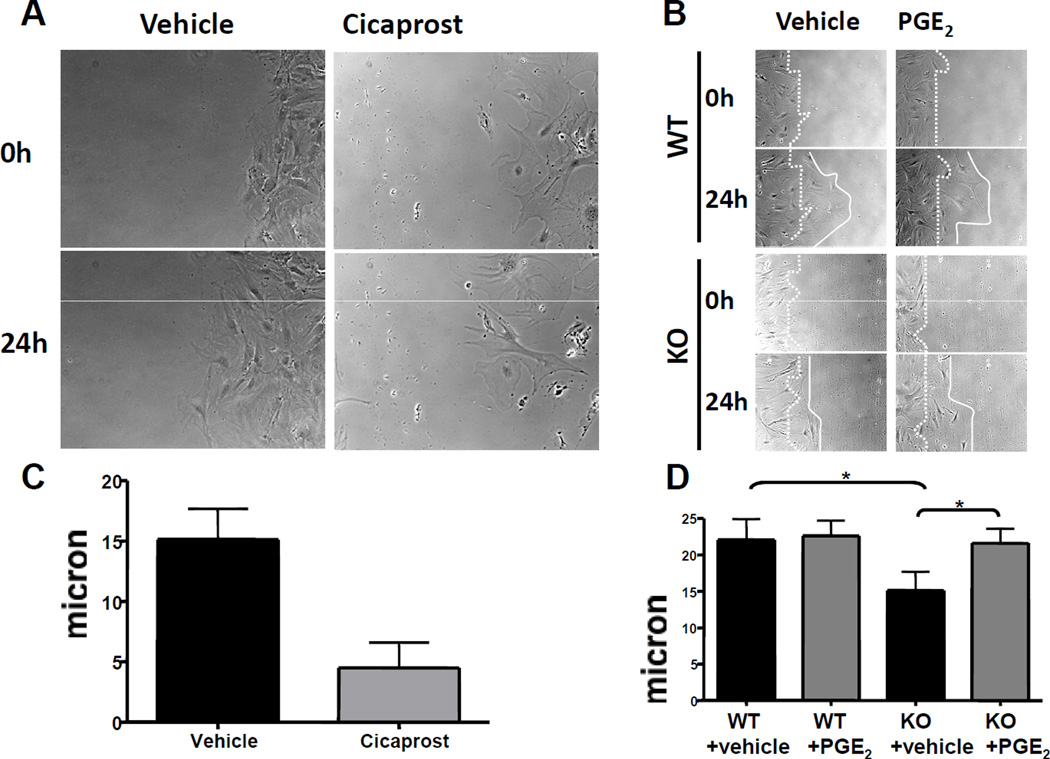

Increased expression of TN-C after injury affords a scaffold upon which VSMC may migrate in the process of neointima formation 41. Consistent with the restraint in expression of TN-C, migration of mPGES-1 KO VSMCs on a collagen coated surface was impaired (Figure 4A, representative movies shown in online Supplementary data). During the initial portion of the motility assays, attachment and spreading of VSMCs from KO mice was delayed (Supplementary Figure 4). mPGES-1 deletion also attenuated VSMC migration in a scratch-induced ‘wound healing’ assay (Figure 4B). Knock-down of TN-C (Supplemental Figure 5) similarly impaired VSMC migration in this assay (Figure 4 C). Treatment with exogenous TN-C partially rescued the impaired migration of mPGES-1 KO VSMCs in the transwell migration assay (Figure 4D). Consistent with their divergent effects on TN-C expression, the IP agonists, iloprost (28 or 280 nM ) and cicaprost42(10nM), each inhibited VSMC migration (Figure 5A&C and data not shown), while PGE2 (28 nM) rescued the impaired migration of mPGES-1 KO VSMCs (Figure 5B&D).

Figure 4. Impaired motility in mPGES-1−/− VSMCs.

VSMC motility was examined for 24 hours after plating VSMCs on collagen thin films, as detailed in methods. Seven or eight movies were recorded for WT or mPGES-1 KO cells that were isolated from two animals of each genotype. VSMC velocity was decreased in mPGES-1 KOs. Distance traveled between each current time point and the immediate past time point was used to calculate velocity at individual time points. The Fisher combined p-vaue is 0.0128 for the two 2-way ANOVA p-values coming from each of the two WT/KO pairs. The scratch wound healing assay (B) also shows that mPGES-1 KO cells (lower panel) migrated more slowly than WT VSMCs (upper panel). Photos shown were taken at base line (0h) and 24 h post wounding, and the dotted line and solid lines demark, respectively, the starting and ending edge of cells during the 24 h scratch healing process. Knock-down TN-C with siRNA results in an impaired healing process (C). Representative graphs of three independent studies with triplicate treatments in each study are shown (B and C). TN-C partially rescues the impaired migration of mPGES-1 KO VSMCs (D). The migration assay was conducted as detailed in the Methods, with a transwell plate that was pre-coated with or without TN-C. **: P<0.01, n=4. Data presented are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 5. Differential impacts of PGE2 and PGI2 signaling on VSMC migration.

A: Treatment of WT VSMCs with 10nM cicaprost significantly inhibits cell migration in the scratch wound healing assay. B: Treatment with PGE2 at 28 nM (upper right two panels) promoted WT VSMC migration, compared to vehicle treated cells (upper left two panels), and rescued the impaired migration in the mPGES-1 KO VSMCs. Photos taken at 0 and 24 hours after wounding are shown. C and D are quantifications of cell migration distance in 24hours (A and B, respectively). Representative photos of three independent studies with triplicate treatments in each study are shown.

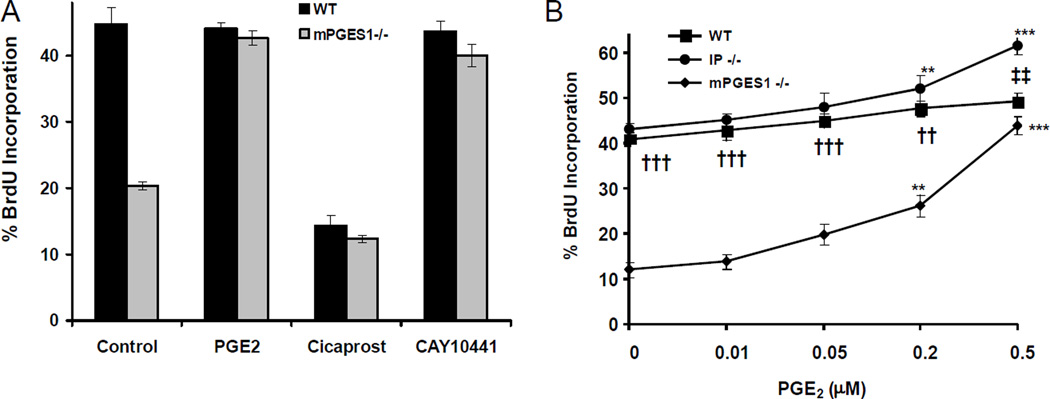

Differential regulation of VSMC cell cycle by PGs in mPGES-1 KOs

VSMC proliferation was also influenced by mPGES-1 deletion. S-phase entry was suppressed in VSMCs cultured from KOs (Figure 6 A & B). PGE2 dose-dependently promoted proliferation and rescued this phenotype (Figure 6A). PGE2 similarly affected proliferation in both WT and IP KO SMCs (Figure 6B) without changing PGI2 release into the media (data not shown), indicating that the proliferative effect of PGE2 does not depend on signaling via the IP. On the other hand, cicaprost inhibits S-phase entry in WT VSMCs, while CAY1044143, an IP antagonist, promotes this phenomenon (Figure 6A). Thus, both suppression of PGE2 and augmentation of PGI2 may each contribute to the restraint on injury induced VSMC proliferation observed in mPGES-1 KOs.

Figure 6. Regulation of S-phase entry in SMCs by mPGES-1 modulated prostanoids.

A: Both WT and KO VSMCs were serum starved for 48 h and stimulated with 2% FBS for 48 h in the absence or presence of PGE2 (0.5 µM), the IP agonist, cicaprost (200 nM) or the IP antagonist, CAY10441 (50 nM). VSMCs were fixed and analyzed for BrdU incorporation by immunofluorescence. The data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. B: Dose-response curve of PGE2 treatment (0.01–1µM) on cell proliferation in WT, mPGES-1 KO and IP KO SMCs. The data are presented as mean ± SD of four independent experiments. PGE2 treatment is compared to baseline for each genotype. (ANOVA with Dunnett’s test. **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001, n=4). At each dose, significant difference between WT and mPGES-1 KO and between WT and IP KO is indicated with † and ‡, respectively. (ANOVA with Bonferroni correction was applied. †† or ‡‡: p < 0.01; †††: p < 0.001, n=4).

Discussion

The role of COX-2 inhibition and mPGES-1 deletion in cardiovascular remodeling is complex. While COX-2 inhibition restrains neointima formation in response to wire- or balloon vascular injury18 19 , it exacerbates the remodeling response to restriction of blood flow in ligated arteries 17. Although global mPGES-1 deletion, unlike COX-2 inhibition, does not increase mortality after coronary artery ligation in mice21, it does adversely influence myocardial remodeling22. Here, we report that in contrast, the vascular remodeling response to injury is restrained in mPGES-1 deficient mice. While the mechanistic distinctions that account for this phenotypic divergence in mPGES-1 KOs is presently unclear, it likely reflects two fundamental properties; the contrasting biological responses evoked by prostanoids and the contrasting predominant products of substrate rediversion products of mPGES-1 deletion in distinct cell types14. Furthermore, despite mPGES-1 deletion, PGE2 formation is actually sustained in the peri - infarct myocardium due to infiltration of myeloid cells expressing alternate PGES enzymes 22, while in the setting of vascular injury, biosynthesis of PGE2 and its formation by VSMC is suppressed.

Intimal hyperplasia is a feature of vascular remodeling, either caused by injury or changes in blood flow. It is characterized by abnormal migration and proliferation of SMCs coincident with de novo deposition of the surrounding ECM 41. TN-C, an ECM glycoprotein is upregulated during neointimal hyperplasia and associated with the synthetic proliferative phenotype of VSMC after balloon injury44, in pulmonary hypertension24 and vascular grafting30, 45. It may afford a scaffold along which proliferating VSMCs can migrate to form the neointima. Interestingly, TN-C is subject to regulation by PGs in this study and others32, 33. Thus, TN-C constitues a focus for mechanistic elucidation of mPGES-1 modulated vascular remodeling. We have demonstrated that the deletion of mPGES-1 attenuates upregulation of TN-C in response to injury and knock down of TN-C impairs VSMC migration in vitro. In VSMCs, the dominant effect of mPGES-1 deletion on VSMC PG formation is to depress PGE2 and to augment PGI2. Cicaprost, a highly selective PGI receptor agonist, dose-dependantly down-regulates TN-C expression in VSMC, while PGE2 slightly upregulates TN-C. In this study, we show that these prostanoids have contrasting effects on TN-C expression and thereby, may both have contributed to the impact of mPGES-1 on VSMC migration and proliferation. It is possible that mPGES-1 deletion may regulate expression of other ECM molecules besides TN-C, which may mediate VSMC behavior. Global production of ECM was examined, as reflected by trichrome stain (Supplemental Figure 6). ECM was increased by injury in both WT arteries and mPGES-1 KOs, however the composition of ECM cannot be identified by this approach and awaits elucidation.

Deletion of mPGES-1 also suppresses VSMC proliferation in response to vascular injury. This response is mimicked by knockdown of TN-C (Supplemental Figure 7). As with VSMC migration, the effects of mPGES-1 deletion on both PGE2 and PGI2 may have been relevant. Thus, PGE2 dose dependently restores impaired proliferation of mPGES-1 in mPGES-1 KOs. By contrast, activation of the IP by cicaprost suppresses proliferation in both WT and KO VSMCs. Thus, both depression of PGE2 and augmented formation of PGI2 may each have contributed to the suppression of VSMC proliferation in mPGES-1 KO mice.

These studies raise the possibility of mPGES-1 inhibition as a strategy to limit restenosis after PCI. However, a limitation may prove to be the contrasting effect on myocardial remodeling after coronary ligation 22. Despite the risk of myocardial infarction conferred by celecoxib in placebo controlled trials1–3, preliminary evidence suggests that in patients receiving platelet inhibitors to limit this risk, restenosis might be reduced by this pdNSAID selective for inhibition of COX-2 20. While mPGES-1 inhibitors might be expected to confer a diminished risk of myocardial infarction compared to COX-2 inhibitors 11, the comparative safety and efficacy of these compounds in the setting of PCI remains to be determined.

In summary, deletion of mPGES-1 decreases vascular injury-induced VSMC proliferation, in part by regulating TN-C expression and subsequent neointimal hyperplasia. Both suppression of PGE2 and augmented formation of PGI2 may contribute to these effects. The therapeutic potential of locally delivered mPGES- 1 inhibitors as an adjuvant for PCI merits further consideration.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs specific for the inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) confer a risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Microsomal (m) prostaglandin (PG) E2 synthase (S)-1 represents an alternative anti-inflammatory target downstream COX-2. Inhibition of mPGES-1 may be less likely to predispose patients to thrombotic events than inhibition of COX-2. Despite the risk of myocardial infarction conferred by celecoxib in placebo controlled trials, preliminary evidence suggests that in patients receiving platelet inhibitors to limit this risk, restenosis might be reduced by this purposefully designed (pd)NSAID selective for inhibition of COX-2. Here, we demonstrate that deletion of mPGES-1 in mice attenuates neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury. Both suppression of PGE2 and rediversion of the accumulated PGH2 substrate to PGI2 may contribute to dysregulated expression of tenascin-C — an extracellular matrix glycoprotein, resulting in impaired vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) migration and proliferation in the knockouts. These studies raise the possibility of mPGES-1 inhibition as a strategy to limit restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). However, a limitation may prove to be the contrasting effect on myocardial remodeling after coronary ligation. While mPGES-1 inhibitors might be expected to confer a diminished risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and mortality after MI, compared to COX-2 inhibitors, the safety and efficacy of these compounds in the setting of PCI remains to be determined. The therapeutic potential of locally delivered mPGES- 1 inhibitors as an adjuvant for PCI merits further consideration.

Acknowledgments

Technical support was kindly provided by Weili Yan, Bao Ha, Helen Zou, Wenxuan Li-Feng, Graham King, Catherine Steenstra, Yubing Yao, and Lucia Xiong.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by American Heart Association [0735397N to Dr. Wang, 09SDG2080312 to Dr. Ihida-Stansbury] and the National Institutes of Health [HL083799 to Dr. FitzGerald, HL083367 and HL62250 to Dr. Assoian].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Dr. FitzGerald is the McNeil Professor of Translational Medicine and Therapeutics. He has consulted in the past year for Astra Zeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Logical Therapeutics, Lilly and Nicox on NSAIDs and related compounds.

References

- 1.Bresalier RS, Sandler RS, Quan H, Bolognese JA, Oxenius B, Horgan K, Lines C, Riddell R, Morton D, Lanas A, Konstam MA, Baron JA. Cardiovascular events associated with rofecoxib in a colorectal adenoma chemoprevention trial. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1092–1102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon SD, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Wittes J, Fowler R, Finn P, Anderson WF, Zauber A, Hawk E, Bertagnolli M. Cardiovascular risk associated with celecoxib in a clinical trial for colorectal adenoma prevention. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1071–1080. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FitzGerald GA. Cox-2 in play at the aha and the fda. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosser T, Yu Y, FitzGerald GA. Emotion recollected in tranquility: Lessons learned from the cox-2 saga. Ann Rev Med. 2010;61:17–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-011209-153129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakobsson PJ, Thoren S, Morgenstern R, Samuelsson B. Identification of human prostaglandin e synthase: A microsomal, glutathione-dependent, inducible enzyme, constituting a potential novel drug target. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7220–7225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trebino CE, Stock JL, Gibbons CP, Naiman BM, Wachtmann TS, Umland JP, Pandher K, Lapointe JM, Saha S, Roach ML, Carter D, Thomas NA, Durtschi BA, McNeish JD, Hambor JE, Jakobsson PJ, Carty TJ, Perez JR, Audoly LP. Impaired inflammatory and pain responses in mice lacking an inducible prostaglandin e synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9044–9049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332766100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuelsson B, Morgenstern R, Jakobsson PJ. Membrane prostaglandin e synthase-1: A novel therapeutic target. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:207–224. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murakami M, Kudo I. Prostaglandin e synthase: A novel drug target for inflammation and cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:943–954. doi: 10.2174/138161206776055912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pini B, Grosser T, Lawson JA, Price TS, Pack MA, FitzGerald GA. Prostaglandin e synthases in zebrafish. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:315–320. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000152355.97808.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanioka T, Nakatani Y, Semmyo N, Murakami M, Kudo I. Molecular identification of cytosolic prostaglandin e2 synthase that is functionally coupled with cyclooxygenase-1 in immediate prostaglandin e2 biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32775–32782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng Y, Wang M, Yu Y, Lawson J, Funk CD, Fitzgerald GA. Cyclooxygenases, microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1, and cardiovascular function. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1391–1399. doi: 10.1172/JCI27540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Francois H, Facemire C, Kumar A, Audoly L, Koller B, Coffman T. Role of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase 1 in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1466–1475. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Facemire CS, Griffiths R, Audoly LP, Koller BH, Coffman TM. The impact of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase 1 on blood pressure is determined by genetic background. Hypertension. 2010;55:531–538. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.145631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Zukas AM, Hui Y, Ricciotti E, Pure E, FitzGerald GA. Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 augments prostacyclin and retards atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14507–14512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606586103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang M, Lee E, Song W, Ricciotti E, Rader DJ, Lawson JA, Pure E, FitzGerald GA. Microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 deletion suppresses oxidative stress and angiotensin ii-induced abdominal aortic aneurysm formation. Circulation. 2008;117:1302–1309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.731398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y, Austin SC, Rocca B, Koller BH, Coffman TM, Grosser T, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Role of prostacyclin in the cardiovascular response to thromboxane a2. Science. 2002;296:539–541. doi: 10.1126/science.1068711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudic RD, Brinster D, Cheng Y, Fries S, Song WL, Austin S, Coffman TM, FitzGerald GA. Cox-2-derived prostacyclin modulates vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2005;96:1240–1247. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000170888.11669.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang HM, Kim HS, Park KW, You HJ, Jeon SI, Youn SW, Kim SH, Oh BH, Lee MM, Park YB, Walsh K. Celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, reduces neointimal hyperplasia through inhibition of akt signaling. Circulation. 2004;110:301–308. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135467.43430.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang K, Tarakji K, Zhou Z, Zhang M, Forudi F, Zhou X, Koki AT, Smith ME, Keller BT, Topol EJ, Lincoff AM, Penn MS. Celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, decreases monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression and neointimal hyperplasia in the rabbit atherosclerotic balloon injury model. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2005;45:61–67. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200501000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koo BK, Kim YS, Park KW, Yang HM, Kwon DA, Chung JW, Hahn JY, Lee HY, Park JS, Kang HJ, Cho YS, Youn TJ, Chung WY, Chae IH, Choi DJ, Oh BH, Park YB, Kim HS. Effect of celecoxib on restenosis after coronary angioplasty with a taxus stent (corea-taxus trial): An open-label randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:567–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu D, Mennerich D, Arndt K, Sugiyama K, Ozaki N, Schwarz K, Wei J, Wu H, Bishopric NH, Doods H. Comparison of microsomal prostaglandin e synthase-1 deletion and cox-2 inhibition in acute cardiac ischemia in mice. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2009;90:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degousee N, Fazel S, Angoulvant D, Stefanski E, Pawelzik SC, Korotkova M, Arab S, Liu P, Lindsay TF, Zhuo S, Butany J, Li RK, Audoly L, Schmidt R, Angioni C, Geisslinger G, Jakobsson PJ, Rubin BB. Microsomal prostaglandin e2 synthase-1 deletion leads to adverse left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117:1701–1710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.749739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones PL, Boudreau N, Myers CA, Erickson HP, Bissell MJ. Tenascin-c inhibits extracellular matrix-dependent gene expression in mammary epithelial cells. Localization of active regions using recombinant tenascin fragments. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 2):519–527. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.2.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones PL, Rabinovitch M. Tenascin-c is induced with progressive pulmonary vascular disease in rats and is functionally related to increased smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res. 1996;79:1131–1142. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taraseviciute A, Vincent BT, Schedin P, Jones PL. Quantitative analysis of three-dimensional human mammary epithelial tissue architecture reveals a role for tenascin-c in regulating c-met function. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:827–838. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones PL, Crack J, Rabinovitch M. Regulation of tenascin-c, a vascular smooth muscle cell survival factor that interacts with the alpha v beta 3 integrin to promote epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation and growth. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:279–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKean DM, Sisbarro L, Ilic D, Kaplan-Alburquerque N, Nemenoff R, Weiser-Evans M, Kern MJ, Jones PL. Fak induces expression of prx1 to promote tenascin-c-dependent fibroblast migration. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:393–402. doi: 10.1083/jcb.jcb.200302126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young SL, Chang LY, Erickson HP. Tenascin-c in rat lung: Distribution, ontogeny and role in branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 1994;161:615–625. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowan KN, Jones PL, Rabinovitch M. Regression of hypertrophied rat pulmonary arteries in organ culture is associated with suppression of proteolytic activity, inhibition of tenascin-c, and smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Circ Res. 1999;84:1223–1233. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto K, Onoda K, Sawada Y, Fujinaga K, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Shimpo H, Yoshida T, Yada I. Tenascin-c is an essential factor for neointimal hyperplasia after aortotomy in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawada Y, Onoda K, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Maruyama J, Yamamoto K, Yoshida T, Shimpo H. Tenascin-c synthesized in both donor grafts and recipients accelerates artery graft stenosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schermuly RT, Yilmaz H, Ghofrani HA, Woyda K, Pullamsetti S, Schulz A, Gessler T, Dumitrascu R, Weissmann N, Grimminger F, Seeger W. Inhaled iloprost reverses vascular remodeling in chronic experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:358–363. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200502-296OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noda N, Minoura H, Nishiura R, Toyoda N, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Sakakura T, Yoshida T. Expression of tenascin-c in stromal cells of the murine uterus during early pregnancy: Induction by interleukin-1 alpha, prostaglandin e(2), and prostaglandin f(2 alpha) Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1713–1720. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sata M, Maejima Y, Adachi F, Fukino K, Saiura A, Sugiura S, Aoyagi T, Imai Y, Kurihara H, Kimura K, Omata M, Makuuchi M, Hirata Y, Nagai R. A mouse model of vascular injury that induces rapid onset of medial cell apoptosis followed by reproducible neointimal hyperplasia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2097–2104. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Damera G, Zhao H, Wang M, Smith M, Kirby C, Jester WF, Lawson JA, Panettieri RA., Jr Ozone modulates il-6 secretion in human airway epithelial and smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L674–L683. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90585.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein EA, Yung Y, Castagnino P, Kothapalli D, Assoian RK. Cell adhesion, cellular tension, and cell cycle control. Methods Enzymol. 2007;426:155–175. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)26008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kothapalli D, Zhao L, Hawthorne EA, Cheng Y, Lee E, Pure E, Assoian RK. Hyaluronan and cd44 antagonize mitogen-dependent cyclin d1 expression in mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:535–544. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott JT, Woodward JT, Langenbach KJ, Tona A, Jones PL, Plant AL. Vascular smooth muscle cell response on thin films of collagen. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDaniel DP, Shaw GA, Elliott JT, Bhadriraju K, Meuse C, Chung KH, Plant AL. The stiffness of collagen fibrils influences vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Biophys J. 2007;92:1759–1769. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schror K, Darius H, Matzky R, Ohlendorf R. The antiplatelet and cardiovascular actions of a new carbacyclin derivative (zk 36 374)--equipotent to pgi2 in vitro. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1981;316:252–255. doi: 10.1007/BF00505658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davies MG, Hagen PO. Pathobiology of intimal hyperplasia. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1254–1269. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skuballa W, Schillinger E, Sturzebecher CS, Vorbruggen H. Synthesis of a new chemically and metabolically stable prostacyclin analogue with high and long-lasting oral activity. J Med Chem. 1986;29:313–315. doi: 10.1021/jm00153a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark RD, Jahangir A, Severance D, Salazar R, Chang T, Chang D, Jett MF, Smith S, Bley K. Discovery and sar development of 2-(phenylamino) imidazolines as prostacyclin receptor antagonists [corrected] Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1053–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hedin U, Holm J, Hansson GK. Induction of tenascin in rat arterial injury. Relationship to altered smooth muscle cell phenotype. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:649–656. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujinaga K, Onoda K, Yamamoto K, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Takao M, Shimono T, Shimpo H, Yoshida T, Yada I. Locally applied cilostazol suppresses neointimal hyperplasia by inhibiting tenascin-c synthesis and smooth muscle cell proliferation in free artery grafts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.