Abstract

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial to determine feasibility and acceptability of a patient navigation intervention. 47 smokers from one safety-net hospital were randomized to either a control condition, receiving a smoking cessation brochure and a list of smoking cessation resources; or to navigation condition, receiving the brochure/list of resources, as well as patient navigation. Follow-up data were obtained on 33 participants. 9/19 (47.4%) of navigation participants had engaged in smoking cessation treatment by three months versus 6/14 (42.9%) of control participants (chi-square p=NS). Patient navigation to promote engagement in smoking cessation treatment was feasible and acceptable to participants.

Keywords: smoking cessation, randomized trials, underserved populations, urban health, vulnerable populations

Cigarette smoking is a significant health threat, responsible for more than 430,000 deaths each year.(Centers for Disease Control, 2010) Low-income persons and some racial and ethnic minorities are at high risk, smoking at greater rates and having greater tobacco-related morbidity and mortality than other persons.(Abidoye, Ferguson, & Salgia, 2007; Kurian & Cardarelli, 2007; Unger et al., 2003; Yancy, 2007) Yet these smokers are less likely to receive advice to quit or to use cessation services.(Cokkinides, Halpern, Barbeau, Ward, & Thun, 2008) A primary care setting is ideal to reach low-income and minority smokers, as 61% of such smokers are engaged in medical care.(K. Lasser)

Few primary care-based interventions have attempted to connect poor and minority smokers to established evidence-based treatments. One approach is the use of proactive telephone support by trained counselors. When combined with free nicotine replacement therapy, proactive telephone support has been shown to promote short-term, but not long-term, smoking cessation in a low-income population.(Solomon et al., 2005) Another approach for poor and minority smokers may be the use of patient navigators. In contrast to counselors providing proactive telephone support, patient navigators guide patients through the health care system to ensure they receive appropriate services (e.g. colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening).(Dohan & Schrag, 2005) Patient navigators are “trained, culturally competent health care workers who work with patients, families, physicians and the health care system to ensure … patients’ needs are appropriately and effectively addressed.”(The Patient Navigator Research Program, 2006) Patient navigation differs from proactive telephone support in the following ways: 1) Many interactions with the navigator occur in-person, prior to or following scheduled appointments; 2) The navigator is not primarily charged with delivering smoking cessation counseling, but rather connecting the smoker with available cessation resources; and 3) The navigator is part of the primary care team, performing some of the tasks traditionally carried out by primary care providers (PCPs), as PCPs face time constraints in their efforts to guide patients through the medical system. This team-based approach to caring for patients is an integral principle in current primary care practice redesign efforts.

Patient navigation has shown promise in reducing health disparities in areas of cancer prevention such as cancer screening. (Battaglia, Roloff, Posner, & Freund, 2007; Fang, Ma, Tan, & Chi, 2007; K. E. Lasser et al., 2009; Percac-Lima et al., 2009) While patient navigation is already being implemented in primary care practices nationwide for a spectrum of health conditions and behaviors, including smoking, (Genesys HealthWorks Health Navigator in the Patient Centered Medical Home, 2008) rigorous research is needed to establish its feasibility and acceptability, and ultimately, its efficacy. To this end, we conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial to study the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of patient navigation to promote linkage to smoking cessation treatment in a primary care setting.

METHODS

Study design

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial, assigning 47 patients in four different primary care practices at an urban safety-net hospital to receive either a low literacy smoking cessation brochure (Massachusetts Health Promotion Clearinghouse, 2010) and a list of hospital and community resources for smoking cessation (enhanced traditional care [ETC] control condition; n = 23), or the brochure and list of resources as well as a maximum of four hours of patient navigation delivered over three months (ETC + navigation condition; n = 24). The patient navigation intervention component encouraged and assisted participants who were ready to quit smoking to enroll in QuitWorks (a fax-referral program offering pro-active telephone counseling), (Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention Program, 2011) call quit lines such as 1–800-QUIT-NOW, join a hospital-based smoking cessation group, or visit their PCP to discuss cessation, prescription medications and/or nicotine replacement therapy. Outcome measures included measures of feasibility (recruitment and retention) as well as engagement in smoking cessation treatment assessed at three-month follow-up. The Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Setting, participants, screening, and randomization

Boston Medical Center is an urban safety-net hospital with academic general internal medicine practices predominantly serving a low-income population. All practices use a common electronic health record (Centricity, General Electric Corporation) that supports computerized ordering of referrals. We included a sample of patients age ≥ 18 who smoked cigarettes in the past week, had a scheduled visit with a PCP in the next six months, had a telephone, spoke English, and were able and willing to participate in the study protocol and provide informed consent. We excluded patients who were planning to move out of the area within the next six months or who had a transient residence; who had cognitive impairments that precluded participation in study activities or who had severe illness or distress; or who were actively using evidence-based smoking cessation treatment.

A research assistant distributed informational sheets about the study in the practice waiting rooms, screening all patients to determine if they were smokers. Among potentially eligible smokers, she then administered a brief pre-screening survey to determine eligibility and assess stage of change (Prochaska, Redding, & Evers, 2002) with respect to smoking cessation, according to the following categories: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, or action. She then obtained written informed consent for eligible participants interested in participating. We randomized individual participants using the Urn Randomization Program (University of Connecticut Health Center, 2005) which allows for randomization of participants to two randomization groups while balancing on additional variables. We balanced the groups based on stage of change with respect to smoking cessation, enrolled participants from October 2011 to March 2012, and followed them for three months following enrollment.

INTERVENTION

ETC-Control Condition

Participants randomized to the ETC study arm received a low literacy smoking cessation brochure (Massachusetts Health Promotion Clearinghouse, 2010) and a list of hospital and community resources for smoking cessation. This intervention content was common to both treatment conditions, with the control condition standardizing the provision of information regarding evidence-based smoking cessation resources, allowing for a more rigorous evaluation of the patient navigation intervention component. The brochure and list of smoking cessation resources were not part of usual care in the primary care practices.

ETC + Navigation Intervention Condition

In addition to receiving the smoking cessation brochure and list of resources, participants randomized to the ETC + Navigation condition received up to four hours of patient navigation delivered over three months. This entailed a navigator contacting participants, educating them about smoking cessation resources, motivating participants (using motivational interviewing techniques (Lai, Cahill, Qin, & Tang, 2010)) to link with treatment, helping participants decide which treatment to pursue, helping participants make appointments to see their PCP or attend smoking cessation groups, and assessing and addressing socioeconomic problems (e.g. housing instability) that prevented them from being able to consider smoking cessation. One of the objectives of the navigation intervention component was that every participant receives at least one in-person navigation session; we defined this as a minimum intervention dose.

During the initial in-person meeting, the navigator used a structured interview instrument to assess stage of change with respect to cessation, explore barriers to cessation, and educate participants about smoking-related health risks. For participants who were contemplating quitting, the navigator discussed the options of quit lines, the Massachusetts QuitWorks program, smoking cessation groups, and PCP visits. The navigator presented the options in a neutral fashion, and did not emphasize the superiority of one approach over another. The navigator also employed flexible problem solving. For example, a participant with lung cancer who was about to be evicted from his apartment stated that he would be unable to quit smoking until he obtained stable housing (the current housing situation was causing him inordinate stress, which prompted him to smoke). The navigator referred him to the Medical-Legal Partnership at Boston Medical center (Medical-Legal Partnership Boston, 2006–2008) to obtain legal assistance.

Navigator Background, Training and Supervision

The navigator was a female certified nurse’s assistant (age 52), originally from Nicaragua, who was based centrally in the Section of General Internal Medicine. She had completed some college-level education, and had 20 years experience performing patient navigation and community health outreach. Prior to this study, the navigator had received training in motivational interviewing (Lai, et al., 2010) and patient navigation. As part of this study, she received three additional five-hour individual training sessions in September 2011. Developed by the study investigators and delivered by an experienced motivational interviewing trainer, the sessions included lectures and role plays about the following subjects: 1) the principles of motivational interviewing; 2) health risks associated with smoking; 3) logistics (“how-to,” pros, and cons) of different cessation modalities; 4) use of open-ended questions, reflective listening, and summarizing; 5) assessment of patient’s readiness to engage in treatment; and 6) approaches for patients who refuse treatment (pre-contemplation), are willing to think about it (contemplation), or are ready to act (action). (Prochaska J & C., 1986) During study implementation, one study investigator (KEL, who also attended the training sessions) audited transcripts of all in-person meetings the patient navigator had with the intervention participants to assess adherence to the script and motivational interviewing techniques. The study investigator met with the navigator on a bi-weekly basis to provide feedback from the audit of the transcripts, discuss challenges arising during the outreach calls/meetings, and review the use of motivational interviewing techniques.

After randomization, the navigator contacted intervention participants over a three-month period. In the initial three-week period, the patient navigator made up to 11 attempts to call each participant on different days and times (including evenings and weekends). The navigator also left at least two messages for the participant on voice mail or with a family member. If the navigator was unable to contact participants by phone (often due to the fact that many participants were reluctant to use their “pay-as-you-go” cell phone minutes), she tried to meet the participants prior to an upcoming medical appointment. Additionally, she made periodic attempts to contact participants over the remainder of the three-month intervention period.

Measures

The research assistant administered a baseline assessment survey including items about demographics, smoking characteristics such as level of nicotine dependence (measured by the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence), (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991) social support, attitudes about smoking cessation treatment and utilization of such treatment. Since we were interested in identifying barriers to cessation that might be particularly salient for a low socioeconomic status (SES) patient population, we administered the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) (e.g., “how often have you felt things were going your way?”; range: 0–16), the 9-item Abbreviated Hassles Index (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981) (e.g., “being out of work for a month or longer?; range: 0–9), and a 6-item Chaos Scale(Matheny AP, 1995) (e.g., “my life is unstable”; range: 6–30). For all measures, higher numbers indicate higher levels of the reported variable.

We ascertained preliminary efficacy by measuring engagement in smoking cessation treatment at three months. We defined treatment engagement as a dichotomous yes/no variable, based on a) completion of ≥ 1 quit line counseling session (based on self-report) OR b) ≥ 1 PCP visit in which smoking cessation treatment was discussed (participant self-report and medical record review of progress notes) OR c) completion of ≥ 1 session of a BMC smoking cessation group (medical record review). One study investigator (KEL) performed chart reviews; charts were reviewed twice to minimize error. The research assistant ascertained the self-reported elements of the treatment engagement variable at a three-month assessment conducted over the telephone. The three-month assessment also surveyed participants about their stage of change with respect to smoking cessation, and about their satisfaction with the navigator.

Statistical Analyses

We compared groups at baseline to determine whether randomization created equivalent groups, using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Because of significantly different rates of follow-up between the ETC-control and ETC + navigation groups, we performed analyses on those participants with complete data at follow-up as well as intent-to-treat analyses. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). We report two-tailed P values or 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all comparisons.

RESULTS

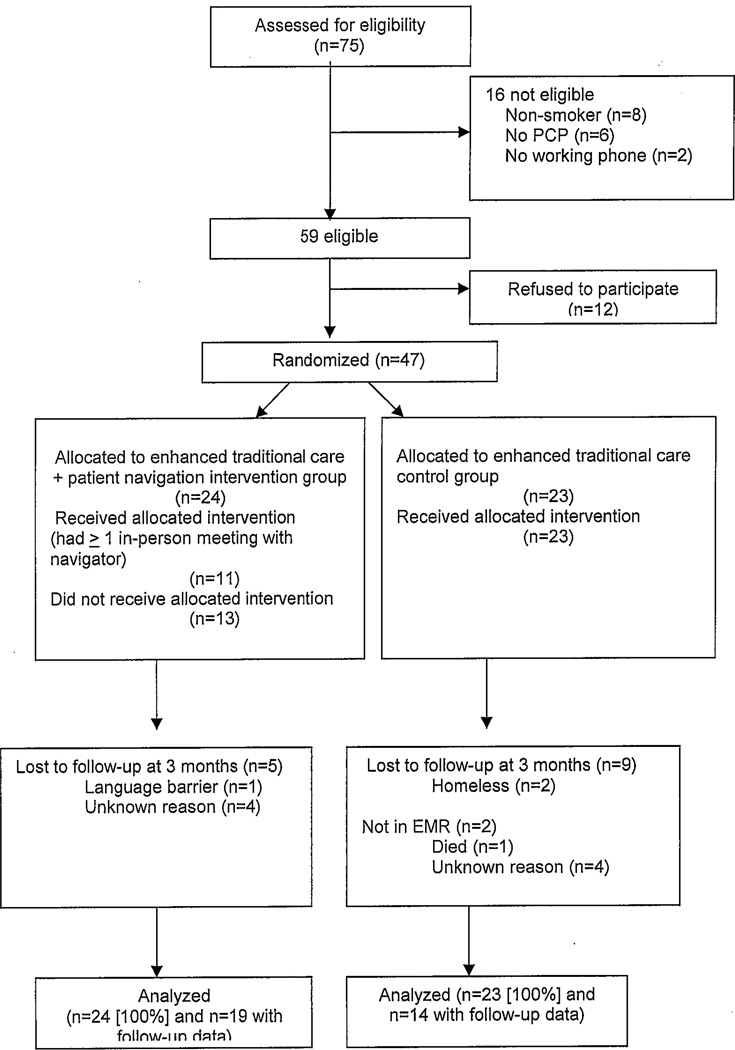

Figure 1 shows the number of participants accrued, randomized, and assessed for the primary outcome. Of the 75 participants screened, 59 were eligible (58.7%), and 47 (79.7%) of these were randomized into the two study arms. The research assistant was able to contact 33 participants (70.2%) by telephone to complete the three-month follow-up assessment: 60.9% of ETC control participants and 79.2% of ETC + navigation participants (p=.17 for differences between study groups). Among the 14 participants lost to follow up, two were homeless, two could not be located in the electronic medical record, one had died, and one had a language barrier; information was not available on the remaining eight participants.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic characteristics of the ETC-control and ETC + navigation groups; randomization resulted in groups with similar demographic characteristics. However, participants in the ETC- navigation group had smoked for fewer years and were more concerned about side effects to nicotine replacement therapy than were ETC-control participants. The mean age of the participants was 45 years; 51% were female. A substantial proportion of participants were non-white, low-income, and unemployed. Most participants had a time frame in mind for quitting and were in the preparation stage. One-fifth of respondents felt supported to quit by neither their PCP nor loved ones, and many participants were suspicious of nicotine replacement therapy. Levels of stress, daily hassles, and lifestyle chaos were high in the sample, but did not differ significantly between the ETC-control and ETC + navigation groups.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, tobacco-related, and psychosocial characteristics of sample by study condition.

| Characteristic | Enhanced Traditional Care Control Condition n= 23 (%) |

Enhanced Traditional Care+ Navigation n=24 (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and health characteristics | |||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 46.8 (11.3) | 42.9 (11.5) | 0.25 |

| Gender, female | 43.5 | 58.3 | 0.31 |

| Race | |||

| White | 36.4 | 29.2 | 0.60 |

| Non-White | 63.6 | 70.8 | |

| Hispanic | 13.0 | 25.0 | 0.30 |

| Household income ≤ $10,000 | 42.1 | 30.4 | 0.43 |

| Unemployed | 82.6 | 73.9 | 0.47 |

| Less than high school graduate | 17.4 | 20.8 | 0.76 |

| Married/living with a partner | 21.7 | 29.2 | 0.56 |

| In fair or poor health | 52.2 | 29.2 | 0.11 |

| Smoking characteristics | |||

| Time frame in mind for quitting | 69.6 | 62.5 | 0.61 |

| Stage of change regarding | |||

| Smoking cessation | |||

| Preparation | 68.8 | 53.3 | 0.38 |

| Contemplation | 18.7 | 26.7 | 0.60 |

| Precontemplation | 12.5 | 20.0 | 0.57 |

| Mean cigarettes/day, (SD) | 13.7 (5.4) | 11.8 (6.4) | 0.27 |

| Years smoked, (SD) | 30.6 (12.2) | 24.4 (9.4) | 0.06 |

| Mean age at initiation, years (SD) | 15.6 (5.0) | 14.9 (3.7) | 0.59 |

| Mean Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence score (SD) | 4.9 (2.0) | 3.9 (2.4) | 0.13 |

| Quit attempt in past year | 56.5 | 54.2 | 0.87 |

| Mean confidence to quit (1–10), (SD) | 5.0 (2.3) | 5.6 (2.3) | 0.39 |

| Utilization of treatment/attitudes about treatment | |||

| Asked primary care provider (PCP) about ways to quit | 69.6 | 62.5 | 0.61 |

| PCP advised to quit | 78.3 | 70.8 | 0.56 |

| Felt very supported/supported to quit by PCP | 52.2 | 45.8 | 0.66 |

| Felt very supported/supported to quit by loved ones | 52.4 | 50.0 | 0.87 |

| Felt very supported/supported to quit by neither loved ones nor PCP | 23.8 | 20.8 | 0.81 |

| Heard of quit line | 43.5 | 54.2 | 0.46 |

| Aware of local programs to quit | 73.9 | 62.5 | 0.40 |

| Concerned about side effects to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) | 43.5 | 79.2 | 0.01 |

| Suspicious of NRT | 47.8 | 50.0 | 0.88 |

| Concerned about dependence on NRT | 59.1 | 54.5 | 0.76 |

| Don’t need NRT to quit | 30.4 | 50.0 | 0.18 |

| Psychosocial characteristics | |||

| Mean Perceived Stress Scale (0–16) score, (SD) | 8.0 (3.2) | 7.0 (3.9) | 0.33 |

| Mean Hassles index (0–9), (SD) | 4.5 (2.5) | 3.8 (3.1) | 0.38 |

| Mean Chaos Scale (6–30), (SD) | 18.8 (4.5) | 16.5 (6.3) | 0.16 |

| Smoking falls near top of the list of things participants think or worry about | 43.5 | 37.5 | 0.68 |

Intervention Feasibility

The navigator was able to reach 19 (79.2%) of the 24 intervention participants, either in person or by telephone. She reached six participants (25.0%) by telephone alone, one (4.2%) only in an in-person meeting, and twelve (50.0%) by telephone and in an in-person meeting. Of the 13 participants whom the navigator met in person, two were unable to receive any navigation because of a language barrier that was not detected during screening (n=1) and very limited participant availability (n=1). Thus, 11 of the 24 patients allocated to the navigation arm (46%) received a minimum dose of the navigator intervention. The navigator spent a mean of 234 minutes navigating each of these 11 participants, which included time on the phone, sending e-mails regarding the participant, time spent in person with the participant, and maintaining a tracking log. While the navigator was allotted a maximum of 240 minutes to navigate each participant, she exceeded this limit among four participants, since she had “extra” navigation time that was unused on participants she was unable to contact. The navigator made a median of 2.5 telephone calls per participant (interquartile range, 1.5–3.5) and a total of two home visits. None of the participants refused additional navigation after the first contact.

Barriers to Treatment Engagement and Satisfaction with Patient Navigator

Table 2 summarizes the main barriers to smoking cessation treatment engagement reported by participants to the navigator. These included stress, financial problems, health beliefs about the effectiveness of nicotine and quit lines, medical illness, mental health symptoms, and hospital systems. Barriers encountered among people who engaged and did not engage in treatment were not appreciably different. One participant could not overcome barriers of housing problems to engage in treatment despite the navigator’s efforts to link the participant to legal and social services assistance. While the navigator perceived one participant’s mental and medical illness as being insurmountable barriers; and felt that she had inadequate time to navigate another participant, both of these participants achieved the goal of engagement in treatment. Two participants were firmly in the pre-contemplation stage and the navigator did not succeed in linking them to treatment in the three-month study period. One participant encountered major systems problems which prevented her from joining the hospital’s smoking cessation program (she was sent a letter with an incorrect date for the program; when the patient navigator attempted to call the clinic on her behalf, the staff answering the phone were not familiar with the program and kept the navigator on hold for twenty minutes); financial problems (an inability to afford minutes on her cell phone) prevented this participant from engaging in telephone counseling. The navigator successfully linked six participants who were motivated to quit smoking to treatment.

Table 2.

Barriers to Treatment Engagement

| Life experiences |

| Stress |

| [I] “could not even think about talking about smoking” [when the] “stress is killing me” [due to not having anything to eat at the house]. |

| “That they keep on denying me the help…I have struggled so much for it [SSI] and this has me very stressed…they denied it three times” [the stress makes patient smoke more] |

| Financial problems |

| One patient was $600.00 behind on her rent, and she had run out of cell phone minutes on her “government” cell phone (she receives 280 minutes per month, but had run out of minutes by the seventh of the month due to many phone calls to and from the hospital for her own medical appointments and those of her grandchildren). |

| Another patient could not participate in telephone quit line counseling because she could not afford minutes on her cell phone. |

| Housing problems |

| “We were paying too much money for a little room … there are a lot of mices (sic), and we call they don’t do nothing, the bathroom is broken, the windows are broken and the cold gets in…[We put] the heat up to 80 degrees but you can’t feel it because it is an old heating system so you spend on gas and heating for nothing because it doesn’t get warm …So I leave the gas alone because I can’t afford to be paying 400 or 500 for gas … so I need to use the electrical heating but the light goes up and this is why I am so stress out smoking…If I had everything fix, I wouldn’t smoke” |

|

Health Beliefs about Nicotine Lack of Trust in Doctors |

| Patient believes drinking a lot of water can help a person to quit smoking: “the water cleanses your system and it cleans the nicotine.” Patient does not believe in using the nicotine patch: “if one wants to quit one should not have any type of nicotine in your system…The doctors won’t tell you but it is true.” |

| Beliefs about quit lines |

| “What is the help line? The help line has nothing to do with people quitting smoking…When people make that decision they do that on their own free will. ‘Don’t buy a pack’ or ‘buy a pack’ ‘don’t buy a carton’ or ‘buy a carton’ … That [counseling] doesn’t stop people from smoking. Be real! … People smoke if they want to smoke…I don’t want to be in no group.” |

| Medical Illness |

| “Because of this illness it’s why smoking is so bad for me, but because of this illness it is why a lot of times I smoke a lot.” |

| Mental health symptoms |

| “When I get anxious in my way to places makes me smoke” |

| Belief that smoking is not causing harm |

| “I know all about it [health effects of smoking]. I don’t care. They checked my lungs and they are all clear…My heart is fine” |

| Family Relationships |

| One patient was concerned about her husband, and felt if he would quit, she would quit. Her daughter also smokes; having several family members who were smoking was a barrier for this patient engaging in treatment. |

| Hospital systems |

| The navigator referred one patient to the hospital smoking cessation group. Major systems problems interfered with the patient being able to attend the group. First, the letter that was sent to the patient had incorrect dates for the group meetings. When the patient tried to attend the group, she was told she could not participate because she had missed the first two sessions. When the navigator contacted the primary care office, the staff was unaware of the smoking cessation program. The navigator was subsequently kept on hold for 20 minutes (prior to hanging up) while waiting to speak with someone knowledgeable about the program. The patient subsequently missed an individual appointment with the smoking cessation counselor. |

Table 3 demonstrates that the majority of participants were satisfied with the interactions they had with the navigator, and did not feel pressured to make changes in their smoking behavior. In the words of one participant: “She [the navigator] was very, very supportive. If I didn't have someone calling me, I probably wouldn't even care about my health overall since I'm getting older. She always lifted me up, and when she'd call or I'd hear her voice, I knew I could try to quit smoking. She was … so caring that it felt like we had been friends even prior to the study. Without that personal care … I never would have cared as much about my own health.”

Table 3.

Participant Satisfaction with Patient Navigator

| Statement | Enhanced Traditional Care + Patient Navigation Condition n=14* % |

|---|---|

| Agree or strongly agree | |

| Navigator is easy to talk to | 92.9 |

| Listen to my problems | 85.7 |

| Is dependable | 92.9 |

| Is easy for me to reach | 85.7 |

| Cares about me personally | 100.0 |

| Is courteous and respectful to me | 100.0 |

| Gives me enough time | 92.9 |

| Figures out the important issues in my health care | 92.9 |

| Makes me feel comfortable | 100.0 |

| Score 4 or 5 on 5-point Likert scale (1= “not at all,” 5= “very much”) |

|

| Extent to which visits with navigator make you think about why you smoke | 71.4 |

| Extent to which visits with navigator make you think about effect of smoking on your family | 85.7 |

| Score 4 or 5 on 5-point Likert scale (1= “not at all,” 5= “very much”); |

|

| Extent to which… | |

| Navigator told you what to do about smoking, without taking your needs into account | 8.3 |

| Navigator understood what you were saying | 85.7 |

| Navigator made it comfortable for you to talk about your smoking | 100.0 |

| You felt pressured by your navigator to make changes | 7.1 |

| You felt like it was up to you to decide whether or not to make changes in your smoking | 100.0 |

| Score 4 or 5 on 5-point Likert scale (1= “not at all,” 5= “very much”); |

|

| Extent to which… | |

| Navigator helped you think about why quitting smoking might be important to you | 92.8 |

| Navigator helped you think about why quitting smoking might be important to your family | 92.8 |

| Navigator helped you feel like you could make changes in your smoking, if you wanted to | 100.0 |

| “Yes” response to Navigator… | |

| Helped you think about good and not so good things about your smoking | 100.0 |

| Talked with you about how smoking helps you to cope with difficulties | 92.9 |

| Offered to help you learn new ways of coping instead of smoking | 92.9 |

| Offered to help you quit (or stay quit) in the future | 92.9 |

| Expressed caring and understanding when talking with you about your smoking | 100.0 |

| Score 4 or 5 on 5-point Likert scale (1= “not at all helpful,” 5= “very helpful”); |

|

| How helpful… | |

| Was it to have your navigator talk with you about smoking? | 100.0 |

| This navigator might be to other smokers? | 100.0 |

| Score 4 or 5 on 5-point Likert scale (1= “not at all satisfied,” 5= “very satisfied”) |

|

| How satisfied were you with the care your navigator provided? | 92.9 |

Note that some respondents did not respond to all survey items.

Three-month outcomes

Of the 33 participants with follow-up survey data, nine of 19 (47.4%) ETC + navigation participants had engaged in smoking cessation treatment by three months after study entry versus six of 14 (42.9%) of ETC-control participants (chi-square p=0.80; Table 4). Among the ETC + navigation participants, two participants reported completing a quit line counseling session, and seven had a visit with their PCP in which smoking cessation treatment was discussed. Among ETC-control participants, six had visited their PCP to discuss smoking cessation treatment. None of the participants in either group had attended a hospital smoking cessation group. Patients in the navigator intervention arm who received the minimum intervention dose had higher rates of treatment engagement (7/10, 70.0%) than controls (6/14, 42.9%), although this difference did not achieve statistical significance (p=0.19). In our secondary intention-to-treat analysis, 37.5% (9 of 24) in the navigation arm vs. 30.4% (7 of 23) in control arm achieved engagement in treatment (p=0.61). Three months after study entry, 36.8% of intervention participants who had initially said that they did not have a time frame in mind for quitting reported that they now had a time frame in mind for quitting, relative to 7.1% of ETC-control participants (Fisher’s exact test p=.09). There were no significant differences in other 3-month outcomes between the two groups.

Table 4.

Three-month Outcomes

| Characteristic | Enhanced Traditional Care Control Condition |

Enhanced Traditional Care+ Navigation Condition |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n= 14 (%) |

n=19 (%) |

||

| Engagement in treatment* | 42.9 | 47.4 | 0.80 |

| Among participants who received minimum intervention dose | 42.9 | 70.0† | 0.19 |

| Established time frame for quitting (% change from “no” to “yes”) | 7.1 | 36.8 | 0.09 |

| Stage of change advanced regarding smoking cessation‡ | 28.6 | 31.6 | 0.85 |

| Smoking moves to near top of the list of things participants think or worry about | 28.6 | 26.3 | 0.89 |

| Smoked cigarettes in past week | 85.7 | 89.5 | 0.74 |

| Mean number of times stopped smoking for ≥ 24 hours not due to illness (SD) | 4.6 (7.6) | 3.5 (6.7) | 0.66 |

Defined as completion of ≥ 1 quit line counseling session (based on self-report) OR ≥ 1 PCP visit in which smoking cessation treatment is discussed (patient self-report and medical record review of progress notes) OR completion of ≥ 1 session of a hospital smoking cessation group (medical record review).

n=10 Enhanced Traditional Care+ Navigation participants received minimum intervention dose, at least one in-person meeting with the navigator.

Defined as moving from pre-contemplation to contemplation, or contemplation to preparation

COMMENT

A patient navigator-based intervention to promote engagement in smoking cessation treatment was feasible and acceptable to low-income and minority patients in a primary care setting. While small numbers of patients enrolled in this pilot study preclude definitive conclusions, there is evidence to suggest that patient navigation may be an effective intervention. First, a higher percentage of intervention participants had engaged in smoking cessation treatment by three months after study entry relative to control participants when the minimum navigation intervention was achieved (70% vs. 43%) – a difference which is clinically, although not statistically, significant. Second, more ETC + navigation participants who had initially said that they did not have a time frame in mind for quitting reported that they now had a time frame in mind for quitting, relative to ETC-control participants (37% vs. 7%).

How might patient navigation be effective in linking patients to treatment? Our finding that one-fifth of respondents lacked support to quit suggests that a patient navigator could play a role in supporting some patients in their efforts to quit smoking. The fact that many participants were suspicious of nicotine replacement therapy suggests a potential role for a navigator to educate participants about the safety of nicotine therapy. Patients may be more apt to believe a navigator they have come to trust, who communicates in a culturally sensitive and accessible fashion. Relative to other published studies, (Romano, Bloom, & Syme, 1991) levels of stress, daily hassles, and lifestyle chaos were high in the sample. This suggests a potential role for a navigator to link patients to social services or simply to help patients through a complex and stressful time which would further improve their ability to access treatment and successfully quit.

It is possible that, as in prior studies, (Solomon, et al., 2005) short-term process outcomes (e.g. speaking with a cessation counselor) do not translate into longer-term sustained smoking cessation outcomes. However, even limited contact of smokers with cessation counseling doubles the odds of quitting. (An et al., 2006; Fiore, Jaen, & Baker, May 2008; Zhu et al., 2002) Prior patient navigation studies (K. Lasser et al., 2011; Phillips et al., 2011) have demonstrated how navigators can motivate patients to engage in short-term behavior change such as undergoing a one-time procedure (e.g. colonoscopy or mammogram). While patient navigation may be sufficient to change short-term behaviors such as participation in screening, it may not be sufficiently intensive to promote longer-term behavior change as is necessary with smoking cessation. It is possible that combining patient navigation with another effective intervention could maximize its impact on promoting engagement in smoking cessation treatment. One such intervention could be financial incentives for smoking cessation (Volpp et al., 2009). Further, multi-component interventions have shown the most promise in reducing health disparities, (Chin, Walters, Cook, & Huang, 2007) suggesting that combining interventions may be one approach to promote smoking cessation among low-income and minority smokers. Patient navigation also may be more effective if targeted to patients who are ready to quit smoking. Two out of the 11 participants who received the minimum intervention dose were in the pre-contemplation stage; had these participants been excluded, the intervention would have been successful in 78% of participants.

Our study has several limitations. Over half of ETC + navigation participants did not receive the minimum intervention dose. Introducing patients to the navigator in the clinic setting, at the time patients express interest in smoking cessation treatment, could increase intervention uptake. Other limitations include a small sample size and differential follow-up across the two treatment arms. In addition, the duration of the intervention was short and the navigator worked part-time. Other successful navigation interventions have taken place over six months and have included full-time navigators.(K. Lasser, et al., 2011) While Lubetkin et al (Lubetkin, Lu, Krebs, Yeung, & Ostroff, 2010) have shown that PCPs serving low-income, racial and ethnic minority patients are interested in providing tobacco-related patient navigation services at their practices, we are unaware of prior studies that have examined the acceptability and feasibility of patient navigation for smoking cessation in practice. Our preliminary findings demonstrate that patient navigation (including a minimum of one face-to-face navigation session) to promote engagement in smoking cessation treatment merits further study.

Acknowledgements

Funding Source: This study was supported by NIH Grant UL1RR025771, funding the Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI). Dr. Wiener is supported by the National Cancer Institute (K07 CA138772) and by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors thank Maxim D. Shrayer for his comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript; and Denise Crooks for her assistance in manuscript preparation.

Role of the Sponsors: This study was supported by the NIH. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Dr. Karen Lasser had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This work was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, May 10, 2012, Orlando, FL.

Financial Disclosure: There are no financial conflicts of interest. I certify that all my affiliations with or financial involvement, within the past 5 years and foreseeable future, with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflicts with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript are completely disclosed.

References

- Abidoye O, Ferguson MK, Salgia R. Lung carcinoma in African Americans. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4(2):118–129. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An LC, Zhu SH, Nelson DB, Arikian NJ, Nugent S, Partin MR, Joseph AM. Benefits of telephone care over primary care for smoking cessation: a randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(5):536–542. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia TA, Roloff K, Posner MA, Freund KM. Improving follow-up to abnormal breast cancer screening in an urban population. A patient navigation intervention. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):359–367. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Smoking & Tobacco Use: Fast Facts Retrieved July 6, 2010. 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fast_facts/index.htm#facts.

- Chin MH, Walters AE, Cook SC, Huang ES. Interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5):7S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides VE, Halpern MT, Barbeau EM, Ward E, Thun MJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in smoking-cessation interventions: analysis of the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2008;34(5):404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104(4):848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Ma GX, Tan Y, Chi N. A multifaceted intervention to increase cervical cancer screening among underserved Korean women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevention. 2007;16(6):1298–1302. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M, Jaen C, Baker T. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service; 2008. May, [Google Scholar]

- Genesys HealthWorks Health Navigator in the Patient Centered Medical Home. 2008 Retrieved July 16, 2012, 2012, from http://www.pcpcc.net/content/genesys-healthworks-health-navigator-patient-centered-medical-home.

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journla of Addiction. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, Lazarus RS. Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. [Comparative Study Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1981;4(1):1–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00844845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian AK, Cardarelli KM. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review. Ethnicity and Disease. 2007;17(1):143–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai DT, Cahill K, Qin Y, Tang JL. Motivational interviewing for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review. 2010;(1):CD006936. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006936.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K. Unpublished analysis of the 2008–2009 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Murillo J, Lisboa S, Casimir N, Valley-Shah L, Emmons K, Ayanian J. Colorectal cancer screening among ethnically diverse, low-income patients: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(10):912–913. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser KE, Murillo J, Medlin E, Lisboa S, Valley-Shah L, Fletcher RH, Ayanian JZ. A multilevel intervention to promote colorectal cancer screening among community health center patients: results of a pilot study. BMC Family Practice. 2009;10:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubetkin EI, Lu WH, Krebs P, Yeung H, Ostroff JS. Exploring Primary Care Providers' Interest in Using Patient Navigators to Assist in the Delivery of Tobacco Cessation Treatment to Low Income, Ethnic/Racial Minority Patients. J Community Health. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Health Promotion Clearinghouse. You Can Quit Smoking: Massachusetts Department of Public Health. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation and Prevention Program. QuitWorks Services for Patients. 2011 Retrieved March 20, 2012, 2012, from http://quitworks.makesmokinghistory.org/about/quitworks-services-for-patients.html.

- Matheny APWT, Ludwig JL, Phillips K. Bring order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1995;16:429–444. [Google Scholar]

- Medical-Legal Partnership Boston. Raising the Bar for Health. 2006–2008 Retrieved June 6, 2012 from http://www.mlpboston.org/

- The Patient Navigator Research Program. 2006 Mar; (2006), 2012, from http://crchd.cancer.gov/attachments/brochures/pnrp_brochure.pdf.

- Percac-Lima S, Grant RW, Green AR, Ashburner JM, Gamba G, Oo S, Atlas SJ. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(2):211–217. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0864-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CE, Rothstein JD, Beaver K, Sherman BJ, Freund KM, Battaglia TA. Patient navigation to increase mammography screening among inner city women. [Comparative Study Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't] Journal of general internal medicine. 2011;26(2):123–129. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1527-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J CD. Toward a comprehensive model of change. In: Miller W, Healther N, editors. Treating Addictive Behaviours: Process of Change. New York: Plenum Pr.; 1986. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J, Redding C, Evers K. The Transtheoretical Model and Stages of Change, in Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Romano PS, Bloom J, Syme SL. Smoking, Social Support, and Hassles in an Urban African-American Community. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81(11):1415–1422. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon LJ, Marcy TW, Howe KD, Skelly JM, Reinier K, Flynn BS. Does extended proactive telephone support increase smoking cessation among low-income women using nicotine patches? Prev Med. 2005;40(3):306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger B, Kemp JS, Wilkins D, Psara R, Ledbetter T, Graham M, Thach BT. Racial disparity and modifiable risk factors among infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):E127–E131. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.e127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Connecticut Health Center. Project MATCH: Urn Randomization. 2005 Retrieved March 8, 2012 from http://www.commed.uchc.edu/match/urn/default.htm.

- Volpp KG, Troxel AB, Pauly MV, Glick HA, Puig A, Asch DA, Audrain-McGovern J. A randomized, controlled trial of financial incentives for smoking cessation. [Randomized Controlled Trial Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.] The New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(7):699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0806819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW. Executive summary of the African-American Initiative. Medscape General Medicine. 2007;9(1):28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, Rosbrook B, Johnson CE, Byrd M, Gutierrez-Terrell E. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(14):1087–1093. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]