Abstract

The effects of inbreeding on the health of offspring can be studied by measuring genome-wide autozygosity as the proportion of the genome in runs of homozygosity (Froh) and relate Froh to outcomes such as psychiatric phenotypes. To successfully conduct these studies, the main patterns of variation for genome-wide autozygosity between and within populations should be well understood and accounted for. Within population variation was investigated in the Dutch population by comparing autozygosity between religious and non-religious groups. The Netherlands have a history of societal segregation and assortment based on religious affiliation, which may have increased parental relatedness within religious groups. Religion has been associated with several psychiatric phenotypes, such as major depressive disorder (MDD). We investigated whether there is an association between autozygosity and MDD, and the extent to which this association can be explained by religious affiliation. All Froh analyses included adjustment for ancestry-informative principal components (PCs) and geographic factors.

Religious affiliation was significantly associated with autozygosity, showing that Froh has the ability to capture within population differences that are not captured by ancestry-informative PCs or geographic factors. The non-religious group had significantly lower Froh values and significantly more MDD cases, leading to a nominally significant negative association between autozygosity and depression. After accounting for religious affiliation, MDD was not associated with Froh, indicating that the relation between MDD and inbreeding was due to stratification.

This study shows how past religious assortment and recent secularization can have genetic consequences in a relatively small country. This warrants accounting for the historical social context and its effects on genetic variation in association studies on psychiatric and other related traits.

Keywords: autozygosity, runs of homozygosity, major depressive disorder, religion, population stratification, assortative mating

Introduction

There is an increasing interest in the association between runs of homozygosity (ROHs) and human disease. Alleles in long ROHs are likely to be identical-by-descent (i.e., autozygous) (Keller et al. 2011). ROHs can have harmful effects through deleterious recessive alleles that combine when related individuals mate and have offspring. Deleterious recessive alleles are usually rare because selection is unable to completely purge such mutations, since they are not damaging to heterozygote carriers; a process known as mutation-selection balance (Charlesworth and Willis 2009). The closer or more recent inbreeding is, the longer the ROHs will be, increasing the chances of combining deleterious recessive alleles in offspring (Szpiech et al. 2013). Studies on the association between autozygosity and psychiatric traits may help provide insights into both the evolutionary history and the genetic etiology of complex psychiatric disorders. Strong selection against deleterious variants should results in a bias toward both rarity and recessivity of causal variants, which in turn should increase damaging effects of inbreeding (DeRose and Roff 1999). Recent reports on autozygosity as a schizophrenia risk factor suggest that purifying (negative) selection caused dominant schizophrenia risk alleles to disappear at a faster rate over evolutionary time than recessive risk alleles (Keller et al. 2012; Lencz et al. 2007). This raises the question to which extent there may be an association between autozygosity and other psychiatric disorders. One of the goals of this study was to evaluate the relation between autozygosity and major depressive disorder (MDD), the most prevalent psychiatric disorder in adults (Kessler et al. 2005; Kessler et al. 1994). In contrast to schizophrenia, MDD is less heritable (31–42%) (Lubke et al. 2012; Sullivan et al. 2000), and has had limited success in identifying reliably associated genetic variants (Ripke et al. 2012; Sullivan et al. 2012).

Before studies on autozygosity can be successfully conducted, the main patterns of variation for autozygosity between and within populations should be well understood and accounted for. Inbreeding is a matter of degree (Keller et al. 2011), and the total length of ROHs reflects relatively recent inbreeding patterns and varies between worldwide populations (McQuillan et al. 2008; Pemberton et al. 2012). This variation is mainly due to a combination of geographic factors leading to isolation and/or bottlenecks and differences in the prevalence of consanguineous matings. Variation within populations may be driven by assortment on cultural factors and attitudes, such as religious beliefs or political preferences (Alford et al. 2011; Watson et al. 2004). Such a positive assortative mating strategy has been hypothesized to improve inclusive fitness by increasing genetic relatedness within groups, which can facilitate communication and altruism (Thiessen and Gregg 1980). Religious affiliation has been reported to facilitate genetic stratification that is detectable by principal component analysis (PCA) on genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (Haber et al. 2013). We investigate whether religious assortment may have led to increased parental relatedness by testing for systematic autozygosity differences within the Netherlands, which is a relatively small country with a high population density. If autozygosity differences exist between religious subgroups, this may affect the outcomes of autozygosity studies on traits associated with religion.

This study focuses on variation in autozygosity within a country that had a long and relatively strict segregation in society based on religious affiliation, with religious groups for example having their own political parties, unions, schools, and universities (Knippenberg 1992), inducing isolation, decreasing mating options, and potentially increasing parental relatedness. Studies on Dutch marriage records of the 19th and early 20th century show considerable religious assortment (Beekink et al. 1998; Kok 1998; Polman 1951). Religion is also associated with geography. The Netherlands can be roughly divided into three regions: (1) below the major rivers, where the population is mainly Catholic; (2) the middle-band, which is largely Orthodox-Protestant; (3) the Northern part, which consists largely of more liberal Protestants (Donk et al. 2006; Knippenberg 1992). These three regions also show subtle genetic differences previously detected by PCA on genome-wide SNPs (Abdellaoui et al. 2013). The geographic distribution of religious groups has been relatively stable for the last four centuries (Knippenberg 1992), and has only started to change in the second half of the last century, due to increasing secularization and the influx of immigrants from other parts of the world (Knippenberg 1992).

Religion shows significant associations with several traits, such as personality and psychiatric disorders (Boomsma et al. 1999; King et al. 2012; Koenig 2009; Miller et al. 2012; Willemsen and Boomsma 2007). Religion and psychiatry display complex associations, with studies showing both stress-buffering as well as depression-evoking effects of religious involvement (Braam et al. 2004; Dein et al. 2010; King et al. 2012; Koenig 2009; Miller et al. 2012; Seybold and Hill 2001). However, the majority of the many studies on the relationship between religiosity and psychiatric disease (in different settings, ethnic backgrounds, age groups, and locations) reports a protective influence of religion on psychiatric disorders (Koenig 2009).

Here, we investigated associations between autozygosity as quantified by ROHs based on genome-wide measured SNPs, major depressive disorder as assessed by DSM4 diagnoses, and self-reported religion to answer whether differences between religious and non-religious groups can lead to a false positive association between ROHs and MDD. Ancestry-informative PCs and living in an urban versus rural environment were accounted for, since ancestry-informative PCs can correlate with homozygosity (Abdellaoui et al. 2013), and larger cities show a higher prevalence for psychiatric disorders (Marcelis et al. 1998; Sundquist et al. 2004; Van Os 2004) and more intermediate values of ancestry-informative PCs due to incoming migration flows (Abdellaoui et al. 2013).

Methods

Participants

Genotyped subjects took part in the Netherlands Twin Register (NTR) biobank project (Boomsma et al. 2006; Willemsen et al. 2010) and in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) (Penninx et al. 2008). The NTR subjects (N=6,685; 2,678 males and 4,007 females) were randomly sampled from twin families across the Netherlands. The NESDA subjects (N=2,380; 806 males, and 1,574 females) were recruited from the general population, primary care and mental healthcare organizations. Analyses were done on unrelated individuals only. Unrelated individuals were chosen using GCTA (Yang et al. 2011), by excluding one of each pair of individuals with an estimated genetic relationship of >0.025 (i.e., more related than third or fourth cousin). There were 4,022 genotyped unrelated individuals with religious affiliation and current living address, and 2,916 genotyped unrelated individuals with religious affiliation, current living address, and MDD case/hyper-control status. Ancestry-informative PCs were computed using 5,166 unrelated subjects and were projected onto the rest of the subjects. In addition to the genotyped subjects, data on religious affiliation were available for 25,450 subjects from the total group of NTR participants. These data were used to display the geographic distribution of religious affiliations and included 3,042 spouse pairs used to test for non-random assortment between spouses on religious affiliation.

Only individuals with Dutch ancestry were included. Individuals with a non-Dutch ancestry were identified by projecting PCs from 1000 Genomes populations on the dataset, and with additional help of the birth country of the parents. This procedure is described in more detail elsewhere (Abdellaoui et al. 2013).

NTR and NESDA studies were approved by the Central Ethics Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects of the VU University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, an Institutional Review Board certified by the US Office of Human Research Protections (IRB number IRB-2991 under Federal-wide Assurance-3703; IRB/institute codes, NTR 03-180, NESDA 03-183). All subjects provided written informed consent.

Phenotypes

Subjects were included as MDD cases when they had a lifetime diagnosis of DSM-IV MDD as determined by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, version 2.1) (WHO 1997). The control group consisted of screened hypercontrols who never scored high on a general factor score for anxious depression and never reported a history of MDD in any survey or at the blood sampling visit (either as a complaint for which treatment was sought, reported medication use, or via the CIDI). Further details on the collection and classification of MDD cases and controls are described elsewhere (Boomsma et al. 2008; Wray et al. 2010). There was a total of 1834 MDD cases and 2131 controls.

Religious affiliation was measured in a longitudinal questionnaire studies in the NTR and NESDA with the question “What is your religion?”. Three answer categories that overlapped between NTR and NESDA were constructed: (1) none (N=2,114), (2) Roman Catholic (N=1,069), and (3) Protestant (N=839).

For the current living addresses, the postal codes were translated into geographic coordinates (longitude and latitude) for each participant using the open source 6PP database (Broek 2012) and used to create Figure 2. Population sizes of the cities were obtained from the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS 2012) and recoded into a dichotomous variable reflecting whether a subject lives in a city with >100k inhabitants.

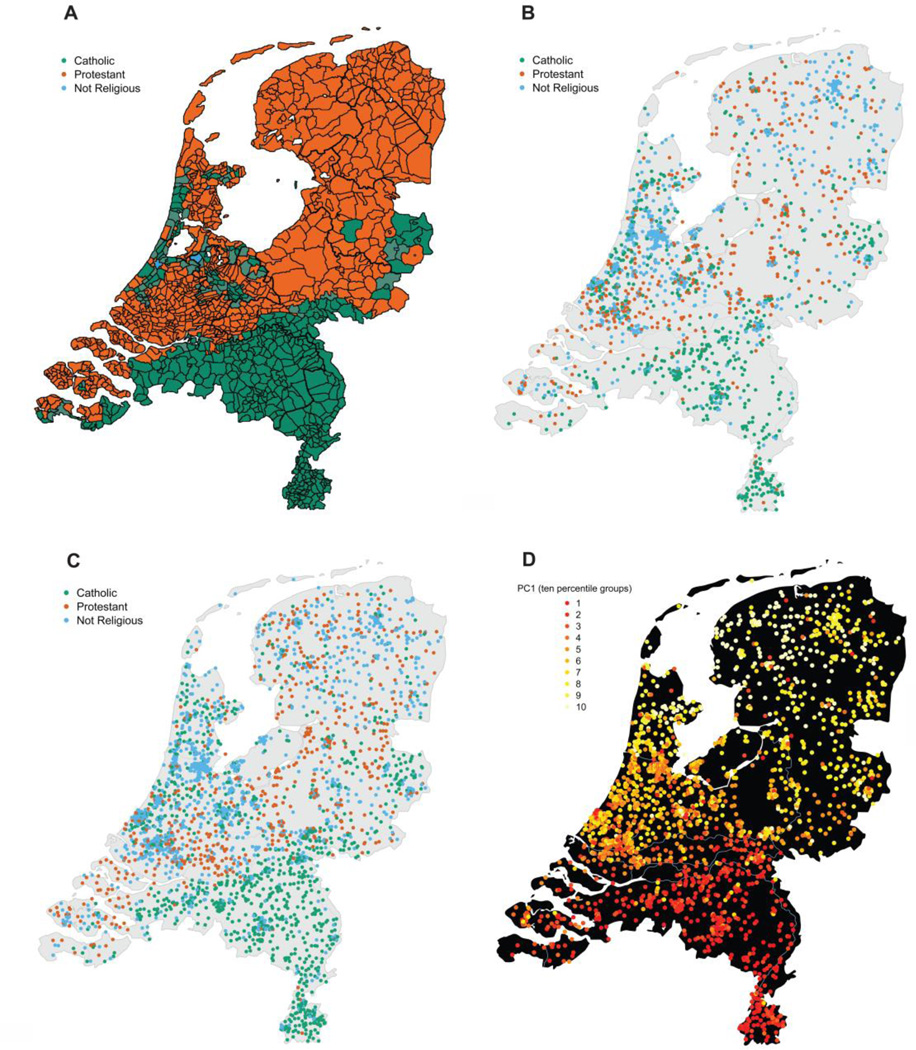

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of religious groups in the Netherlands.

A shows the geographical distribution of Catholic, Protestant and not religious groups in the Netherlands in 1849 (Dimitri 2007; Knippenberg 1992). B and C show the distribution of the current genotyped dataset (including related individuals: N=6,464) and the full dataset with a measurement for religious affiliation respectively (N=25,450). Each postal code was given the color of its most prevalent religious group. D shows the geographic distribution of the North-South PC, where the mean PC value per postal code (current living address) was computed, divided into 10 percentiles, and plotted.

Genotyping, quality control (QC), and principal component analysis (PCA)

Methods for blood and buccal swab collection, genomic DNA extraction, and genotyping have been described previously (Abdellaoui et al. 2013; Scheet et al. 2012). Genotyping was performed on the Affymetrix Human Genome-Wide SNP 6.0 Array (containing ~906,600 SNP probes) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Only autosomal SNPs were analyzed. SNPs were removed if they: (1) had probes that mapped badly against NCBI Build 37/UCSC hg19 (i.e., to a “random” region, to >1 region, or to 0 regions); (2) showed a minor allele frequency (MAF) smaller than 5%; (3) had a missing rate greater than 5%; (4) deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) with a p-value smaller than 0.001. After QC, 498,592 SNPs remained.

Individuals were removed if they: (1) showed a Contrast QC < .4 (CQC, a quality metric from Affymetrix representing how well allele intensities separate into clusters); (2) fell outside of the main cluster of a PC reflecting a batch effect (Abdellaoui et al. 2013); (3) had a missing rate greater than 5%; (4) had excess genome-wide heterozygosity / inbreeding levels (F, as calculated in Plink on an LD-pruned set, must be greater than −0.10 and smaller than 0.10); (5) had non-European/non-Dutch ancestry (Abdellaoui et al. 2013); (6) had genotypes with inconsistencies regarding reported sex or reported relatedness within families.

PCA was conducted using Eigenstrat (Price et al. 2006). The first three PCs correlated significantly with geography: PC1=North-South PC, PC2=East-West PC, PC3=middle-band PC. The procedure for the PCA and the three ancestry-informative PCs are described in detail elsewhere (Abdellaoui et al. 2013).

ROH calling

ROHs were called in Plink (Purcell et al. 2007), which was found to optimally predict autozygous stretches in a recent study comparing several software packages designed for this goal (Howrigan et al. 2011). Howrigan et al (2011) used simulated data based on the Affymetrix 6.0 chip, making their density of SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) close to the data analyzed in our study. We followed their recommendations in calling ROHs: (1) SNPs were pruned for LD (window size = 50, number of SNPs to shift after each step = 5, based on a variance inflation factor [VIF] of 2), resulting in 131,325 SNPs; (2) an ROH was defined as ≥65 consecutive homozygous SNPs with no heterozygote calls allowed. To calculate the proportion of the autosome in ROHs, the total length of ROHs were summed for each individual, and then divided by the total SNP-mappable autosomal distance (2.77 × 109 bases), resulting in the Froh measure.

Statistical analyses

Chi-squared tests were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 19 to test the association between religion and city size, and to test for non-random assortment between spouses on religious affiliation. All other statistical analyses were done in purpose written perl scripts. Regression analyses were computed with the help of the PDL::Stats::GLM perl module (see http://search.cpan.org/~maggiexyz/PDL-Stats-0.6.2/GLM/glm.pp), which allows for the computation of the R2 change and its significance. The R2 change in this study is the difference in explained variance of Froh between regressions with and without the predictor of interest (religious affiliation or MDD). All regressions on Froh also included as predictors: three PCs reflecting ancestry, city size (dichotomous), and Contrast QC (CQC, a quality metric from Affymetrix representing how well allele intensities separate into clusters, and known to correlate with heterozygosity).

Religion and autozygosity

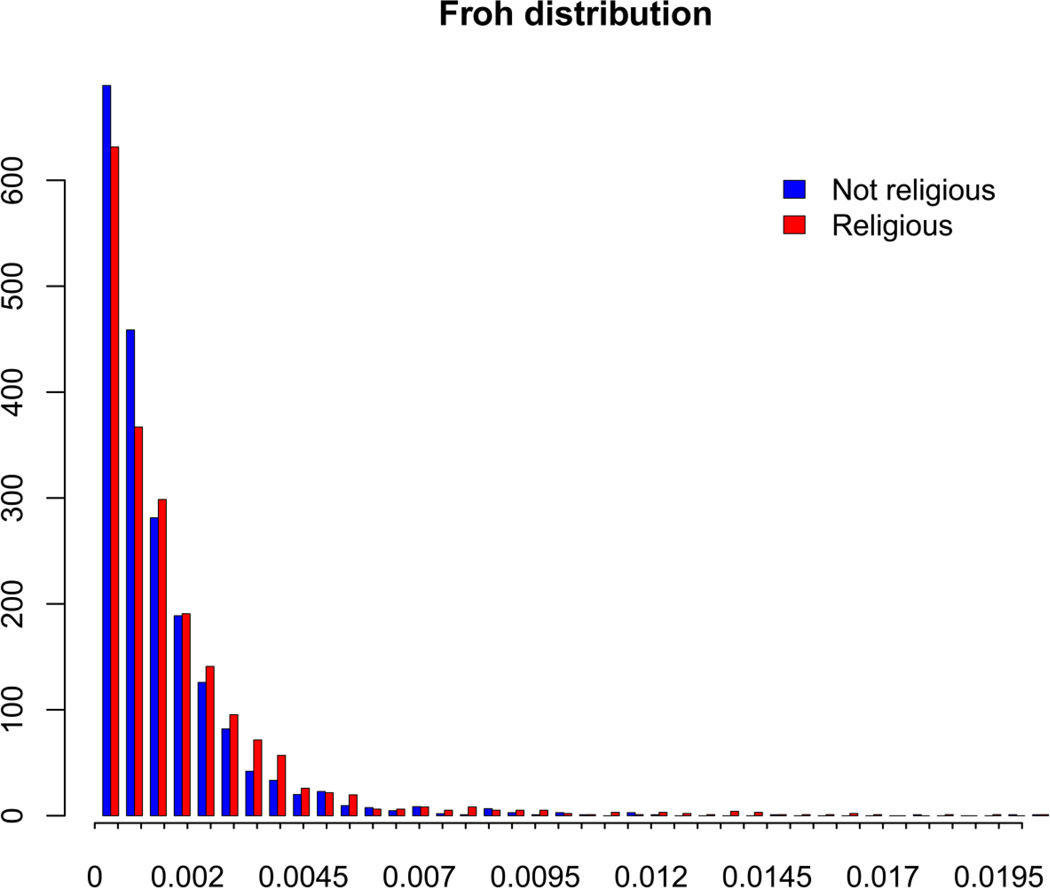

R2 change was computed between multiple regression analyses on Froh with and without religious affiliation as a predictor of Froh. To account for the non-normal distribution of Froh (see Figure 3), Froh was permuted 100,000 times.

Figure 3. Density plot of the Froh distribution for religious and non-religious individuals.

The bars have been scaled to have a total density of 1 for both groups in order to allow a comparison between the groups.

Permutation analyses were repeated using the residual of Froh as the dependent variable, and the residual of religious affiliation as the independent variable (i.e., residuals from regressions on the predictors used as control variables: PCs, city size, and CQC). We performed these analyses in order to check whether the association with the control variables caused a bias in the permutation analyses, since only Froh was permuted. Results (data not shown) were similar and significant in the same directions.

Religion and MDD

A logistic regression analysis was run with MDD case/control status as the dependent variable, and as a predictors religion (religious versus non-religious), and city size (small versus large).

MDD and autozygosity

R2 change was computed between multiple regressions on Froh with and without MDD as a predictor. Analyses were permuted 100,000 times and were repeated adding religion as an additional predictor.

These permutations were also repeated using the residual of Froh and the residual of MDD. The results (data not shown) were similar and significant in the same directions.

ROH mapping analysis

The --homozygous-group command in Plink (Purcell et al. 2007) was used to obtain ROH segments that overlap between individuals. This was done separately for analyses on religious groups (resulting in 2,506 ROH segments, in which 2,879 allelically distinct ROHs were observed in ≥2 individuals) and MDD (resulting in 1,858 ROH segments, in which 1,773 allelically distinct ROHs were observed in ≥2 individuals). Table 3 (column “All subjects”) and Table 4 (row “All subjects”) show the sample sizes for these analyses. Two genome-wide association analyses were conducted: (1) logistic regressions for each ROH segment, where a dichotomous independent variable indicated the presence of an ROH for each individual, which may or may not allelically match; (2) logistic regressions for each allelically distinct ROH, where a dichotomous independent variable indicated the presence of an ROH for each individual. These analyses were done for four dichotomous phenotypes: (1) Catholics versus others, (2) Protestants versus others, (3) non-religious versus others, and (4) MDD cases versus controls. The dependent variable was permuted 1000 times. All regressions were corrected for PCs, city size, and CQC. The analyses for MDD also included religion (dichotomous) as a covariate.

Table 3.

Sample size and mean Froh for each religious group per additional Froh cutoff

| All subjects | ZFroh < 1.96 | Froh < .03125 | Froh < .005 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious group | N | Mean Froh (SD) | N | Mean Froh (SD) | N | Mean Froh (SD) | N | Mean Froh (SD) |

| Catholic | 1,069 | .00159 (.0031) | 1,036 | .00119 (.0013) | 1,067 | .00151 (.0024) | 1,013 | .00109 (.0011) |

| Protestant | 839 | .00186 (.0031) | 806 | .00138 (.0013) | 838 | .00180 (.0026) | 792 | .00131 (.0012) |

| Not Religious | 2,114 | .00133 (.0024) | 2,081 | .00112 (.0012) | 2,112 | .00128 (.0020) | 2,050 | .00105 (.0011) |

Table 4.

Sample size and mean Froh for MDD cases and controls per additional Froh cutoff

| Cases | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean Froh (SD) | N | Mean Froh (SD) | |

| All subjects (N = 2,916) | 1,608 | .00143 (.0025) | 1,308 | .00156 (.0024) |

| ZFroh < 1.96 (N = 2,835) | 1,570 | .00116 (.0012) | 1,265 | .00124 (.0013) |

| Froh < .03125 (N = 2,914) | 1,607 | .00140 (.0022) | 1,307 | .00154 (.0023) |

| Froh < .005 (N = 2,787) | 1,549 | .00110 (.0011) | 1,238 | .00114 (.0011) |

Results

Geographic distribution and assortment on religion

Figure 2 shows that the North-South distribution of Protestants and Catholics in the Netherlands seen in previous generations is maintained today, but with an overall increase (especially in the larger cities displayed in Figure 1) of non-religious groups. When comparing the 26 cities in the Netherlands with a population size >100k with the rest of the Netherlands, the more densely populated cities show significantly fewer religious individuals (χ2(1) = 289.05, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .261). The fact that the North-South distribution of Protestants and Catholics is still visible today may have been influenced by strong religious assortment. Spouse pairs (3,042 pairs who had a measure for religious affiliation) showed highly significant religious assortment (χ2(4) = 3226.67, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .728; see Table 1). Of the 3,042 spouse pairs, 2,486 (81.72%) reported the same religious affiliation (Protestant, Catholic, or no affiliation).

Figure 1.

Map of the Netherlands, its major rivers, and its 26 largest municipalities (population size >100k as of April 2012) (CBS 2012).

Table 1.

Distribution of religious affiliation in 3,042 spouse pairs, including χ2 test for non-random assortment between spouses and the spouse correlation (Cramer’s V).

| χ2 (4) = 3226.67, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .728 |

Wife | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protestant | Catholic | Not Religious | ||

| Husband | Protestant | 646 (202.5) | 52 (324.8) | 69 (239.8) |

| Catholic | 42 (312) | 1049 (500.5) | 91 (369.5) | |

| Not Religious | 115 (288.5) | 187 (462.8) | 791 (341.7) | |

The numbers between brackets is the expected number of spouse pairs in that cell under the null hypothesis of no religious assortment. Observed values higher than the expected values are in bold.

These results confirm the stability of the religious distribution of Catholics and Protestants. The PC explaining most variation, thus showing the greatest ancestry differences in the Dutch population, shows a high correlation with the North-South gradient based on current living address (r=.603), and mainly separates the Catholic and Protestant regions of the Netherlands (see Figure 2d). The association between geographic proximity and shared ancestry within the Catholic and Protestant regions is in line with the stable geographic distribution of religions during the last centuries, and indicates that current religious affiliation (Figures 2b and 2c) is likely to correspond to those of a person’s ancestors (Figure 2a) for Catholics and Protestants.

Religion and autozygosity

Data on religious affiliation were available for 4,022 unrelated individuals with Dutch ancestry in three categories: Catholic (N=1,069; mean Froh = .0016), Protestant (N=839; mean Froh = .0019), and non-religious (N=2,114; mean Froh = .0013). Linear regressions with Froh as the dependent variable were performed to test whether the Froh differences between these three groups were significant. Regressions included: ancestry-informative PCs (PC1=North-South PC, PC2=East-West PC, PC3=middle-band PC), city size, and CQC. To account for the non-normal distribution of Froh (see Figure 3), Froh was permuted 100,000 times.

Without religion as a predictor, only the North-South PC, East-West PC, and city size contributed significantly to Froh variation (see Appendix 1), with the most significant contribution coming from the North-South PC, where the southern part has fewer/shorter ROHs. Including religion in the regression analysis led to a significant increase in explained variance of Froh. Post-hoc analyses showed that this was due to the significant difference between the non-religious group and the two religious groups, since there was no significant difference between the two religious groups (see Table 2, Appendix 1, and Figure 3). To further investigate whether this effect is due to closer inbreeding, we removed subjects with more extreme Froh values and repeated the analyses. When removing the 2.5% tail (ZFroh > 1.96, N=103, of which 66% is religious, compared to 47% of the remaining individuals), the effect remains the same, and significant. Removing outliers with an approximate equivalent of half-cousin inbreeding (Froh > .03125) or even distant inbreeding (Froh > .005) also results in a significant effect (Table 2 and Appendix 1). This suggests that these effects are not due to recent or close inbreeding. The highest observed Froh value was .0583, so there were no individuals with values higher than or equivalent to cousin-cousin inbreeding (Froh > .0625).

Appendix 1.

Regression coefficients (p-values between brackets) for each of the predictors included in the linear regressions.

| Religious Affiliation | Religious Affiliation | PC1 (North-South) | PC2 (East-West) | PC3 (Middle-Band) | City Size | CQC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All available individuals (N=4,022) | |||||||

| No religion included | NA | NA | .0211 (3.96 × 10−11) | .0067(.037) | .0060(.060) | −.0003 (1.77 × 10−4) | .0001 (.102) |

| Two dummy variables | .0004 (.002) | .0004 (1.09 × 10−4) | .0230 (1.09 × 10−11) | .0071 (.025) | .0063 (.052) | −.0002 (.014) | .0001 (.093) |

| Not religious vs. Protestant | NA | .0004 (.001) | .0261(8.56 × 10−11) | −.0010 (.790) | .0107 (.005) | −.0002(.106) | 8.15 × 10−5 (.372) |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | NA | .0004 (3.68 × 10−5) | .0235 (3.79 × 10−11) | .0114 (.001) | .0016 (.657) | −.0002 (.055) | .0002 (.019) |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | NA | −4.76 × 10−5 (.766) | .0207 (1.57 × 10−4) | .0120 (.014) | .0081 (.109) | −.0004 (.011) | .0001 (.366) |

| Individuals with ZFroh < 1.96 (i.e., excluding the 2.5 % tail; N=3,923) | |||||||

| No religion included | NA | NA | .0178 (< 10−15) | .0007 (.644) | −.0030 (.039) | −.0002 (7.65 × 10−5) | .0001 (.001) |

| Two dummy variables | .0002 (.002) | .0002 (7.63 × 10−5) | .0187 (< 10−15) | .0009 (.523) | −.0029 (.052) | −.0001 (.008) | .0001 (.0009) |

| Not religious vs. Protestant | NA | .0002 (.003) | .0228 (< 10−15) | −.0005 (.756) | .0009 (.604) | −4.44 × 10−5 (.341) | 7.93 × 10−5 (.067) |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | NA | .0002 (1.52 × 10−4) | .0175 (< 10−15) | .0023 (.175) | −.0033 (.046) | −.0001 (.010) | .0002 (7.39 × 10−5) |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | NA | 2.25 × 10−6 (.974) | .0168 (6.999e-13) | .0010 (.646) | −.0059 (.0059) | −.0002 (.0017) | .0001 (.019) |

| Individuals with Froh < .03125 (i.e., excluding half-cousin inbreeding; N=4,017) | |||||||

| No religion included | NA | NA | .0205 (2.89 × 10−15) | .0018 (.480) | .0039 (.134) | −.0003 (2.50 × 10−4) | .0001 (.065) |

| Two dummy variables | .0004 (7.49 × 10−5) | .0004 (2.28 × 10−5) | .0219 (1.78 × 10−15) | .0023 (.382) | .0040 (.127) | −.0002 (.029) | .0001 (.056) |

| Not religious vs. Protestant | NA | .0004 (1.44 × 10−4) | .0261 (6.00 × 10−15) | .0005 (.875) | .0090 (.004) | −.0001 (.123) | 8.95 × 10−5 (.238) |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | NA | .0004 (7.12 × 10−6) | .0218 (2.75 × 10−14) | .0046 (.110) | −9.74 × 10−5 (.973) | −.0001 (.109) | .0002 (.011) |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | NA | 3.30 × 10−5 (.798) | .01855 (2.54 × 10−5) | .0014 (.722) | .0048 (.240) | −.0003 (.026) | 9.85 × 10−5 (.365) |

| Individuals with Froh <.005 (i.e., excluding elevated levels of distant inbreeding; N=3,855) | |||||||

| No religion included | NA | NA | .0161 (< 10−15) | .0018 (.182) | −.0024 (.069) | −8.03 × 10−5 (.022) | 9.22 × 10−5 (.006) |

| Two dummy variables | .0002 (7.81 × 10−5) | .0002 (9.61 × 10−5) | .0167 (< 10−15) | .0020 (.136) | −.0024 (.075) | −3.32 × 10−5 (.361) | 9.32 × 10−5 (.005) |

| Not religious vs. Protestant | NA | .0002 (2.31 × 10−4) | .0202 (< 10−15) | .0011 (.492) | .0006 (.708) | 5.85 × 10−6 (.889) | 5.75 × 10−5 (.137) |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | NA | .0002 (1.13 × 10−4) | .0156 (< 10−15) | .0029 (.051) | −.0021 (.159) | −2.41 × 10−5 (.542) | .0001 (.002) |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | NA | 4.60 × 10−5 (.446) | .0149 (9.54 × 10−13) | .0018 (.353) | −.0056 (.004) | −.0001 (.048) | .0001 (.025) |

Table 2.

Results of 100k Permutations of multiple linear regression on Froh, including the three Dutch PCs, whether the subject lives in a city with >100k residents and CQC as predictors.

| Included in model | F (df) | R2 change | p-value | Empirical p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All available individuals (N=4,022) | |||||

| Main test | Two religious groups and non religious group (as two dummy variables) | 9.78 (2 4014) | .005 | 5.80 × 10−5 | 7 × 10−5 |

| Post-hoc tests | Not religious vs. Protestant | 10.27 (1 2946) | .003 | 1.36 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−3 |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | 17.08 (1 3176) | .005 | 3.67 × 10−5 | 8 × 10−5 | |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | .088 (1 1901) | 4.57 × 10−5 | .766 | .770 | |

| Individuals with ZFroh < 1.96 (i.e., excluding the 2.5% tail; N=3,923) | |||||

| Main test | Two religious groups and non religious group (as two dummy variables) | 9.99 (2 3915) | .005 | 4.70 × 10−5 | 3 × 10−5 |

| Post-hoc tests | Not religious vs. Protestant | 8.62 (1 2880) | .003 | 3.35 × 10−3 | 3.18 × 10−3 |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | 14.38 (1 3110) | .004 | 1.52 × 10−4 | 1.8 × 10−4 | |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | .001 (1 1835) | 5.75 × 10−7 | .973 | .973 | |

| Individuals with Froh < .03125 (i.e., excluding half-cousin inbreeding; N=4,017) | |||||

| Main test | Two religious groups and non religious group (as two dummy variables) | 13.08 (2 4009) | .006 | 2.17 × 10−6 | <10−5 |

| Post-hoc tests | Not religious vs. Protestant | 14.49 (1 2943) | .005 | 1.44 × 10−4 | 1.1 × 10−4 |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | 20.23 (1 3172) | .006 | 7.12 × 10−6 | <10−5 | |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | .065 (1 1898) | 3.38 × 10−5 | .798 | .797 | |

| Individuals with Froh < .005 (i.e., excluding elevated levels of distant inbreeding; N=3,855) | |||||

| Main test | Two religious groups and non religious group (as two dummy variables) | 12.04 (2 3847) | .006 | 6.11 × 10−6 | <10−5 |

| Post-hoc tests | Not religious vs. Protestant | 13.59 (1 2835) | .005 | 2.31 × 10−4 | 2.4 × 10−4 |

| Not religious vs. Catholic | 14.94 (1 3056) | .005 | 1.13 × 10−4 | 1.3 × 10−4 | |

| Catholic vs. Protestant | .580 (1 1798) | 3.08 × 10−4 | .446 | .445 | |

Significance threshold for post-hoc tests = .05/3 = 0.0167. Bold = significant.

MDD and autozygosity

Being religious was protective for MDD, while living in a larger city increased the chance for MDD: a logistic regression with MDD case/control status as the dependent variable, religion as a dichotomous (religious versus non-religious) predictor (β = −.84, p < 10−16), and city size as a dichotomous predictor (β = .62, p = 5.71 × 10−15) showed a significant negative relation between MDD and religion and a significant positive relation between MDD and city size.

MDD controls showed higher Froh values than MDD cases for each Froh cutoff (see Table 4). Linear regressions with Froh as the dependent variable were performed that included the three ancestry PCs, city size, and CQC as predictors. We did the analysis for the entire dataset (2,916 unrelated individuals with MDD and religion measured), and repeated it for the datasets excluding positive outliers (i.e., excluding closer inbreeding). MDD showed a nominally significant association with Froh for the dataset excluding the 2,5% Froh tail (significantly more variance is explained with than without MDD as an independent variable: empirical p = .042). When repeating this analysis with religion added as a predictor, the effect disappears (empirical p = .236), while religion remains highly significant (p = 2.09 × 10−5; see Table 5 and Appendix 2).

Table 5.

R2 change, and its significance, between multiple regressions on Froh with and without MDD as independent variable (once with, and once without religion as a covariate). Froh was permuted 100,000 ×.

| F (df) | R2 change | p | Empirical p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals | No religion included | 1.65 (1, 2909) | .0006 | .199 | .200 |

| N = 2,916 | Religion included | .07 (1 2908) | 2.4 × 10−5 | .787 | .788 |

| ZFroh < 1.96 | No religion included | 4.14 (1, 2828) | .0014 | .042 | .042 |

| N = 2,835 | Religion included | 1.41 (1 2827) | .0005 | .235 | .236 |

| Froh < .03125 | No religion included | 2.84 (1, 2907) | .0010 | .092 | .093 |

| N = 2,914 | Religion included | .46 (1 2906) | .0002 | .497 | .496 |

| Froh < .005 | No religion included | 2.51 (1, 2780) | .0009 | .113 | .113 |

| N = 2,787 | Religion included | .71 (1 2779) | .0002 | .400 | .399 |

Appendix 2.

Regression coefficients (p-values between brackets) for each of the predictors included in the linear regressions of the MDD analyses. These results are from analyses done on individuals with ZFroh < 1.96.

| Religious Affiliation (dichotomous) |

MDD | PC1 (North-South) | PC2 (East-West) | PC3 (Middle-Band) | City Size | CQC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Religion & No MDD | NA | NA | .0156 (<10−15) | .0038 (.030) | −.0053 (.002) | −.0001 (.003) | .0001 (.006) |

| No Religion & MDD | NA | −.0001 (.042) | .0159 (<10−15) | .0038 (.031) | −.0052 (.003) | −.0001 (.013) | .0001 (.004) |

| Religion & No MDD | .0002 (4.99 × 10−6) | NA | .0162 (<10−15) | .0042 (.017) | −.0051 (.003) | −7.81 × 10−5 (.097) | .0001 (.005) |

| Religion & MDD | .0002 (2.09 × 10−5) | −5.66 × 10−5 (.235) | .0163 (<10−15) | .0041 (.018) | −.0050 (.003) | −7.00 × 10−5 (.141) | .0001 (.004) |

ROH mapping analysis

In order to test whether specific regions of the genome were overrepresented in one of the religious groups, or in MDD cases/controls, genome-wide analyses were conducted on ROHs. Analyses were done on each ROH segment that showed overlap between individuals. Each segment was tested in genome-wide analyses with the following dichotomous dependent variables: (1) Catholics versus others, (2) Protestants versus others, (3) non-religious versus others, and (4) MDD cases versus controls (see Tables 3–4 for sample sizes). Association analyses were run on (1) the overall burden of ROHs at each location throughout the genome, and (2) on each allelically distinct ROH. All regressions included the three ancestry PCs, city size, and CQC as covariates, and the analyses for MDD also included religion as a covariate. There were no significant results (all empirical p’s > .05), indicating no association between specific genomic regions and religion or MDD.

Discussion

We observed significant autozygosity differences between religious and non-religious groups, due to by greater levels of background parental relatedness in the religious groups and a more outbred non-religious group. Individuals with the same religious affiliation are more likely to share ancestry due to a combination of geographic proximity and the strong assortment and segregation of religious groups throughout the past centuries. The non-religious group showed a significantly lower ROH burden, which could not be explained by the fact that these groups are more prevalent in urban areas that attract people with a greater variation in genetic background. The decrease of ROHs in non-religious groups is likely caused by increasing variation in the gene pool of possible mates, induced by the relatively recent absence of denominational restrictions on mate selection.

In the non-religious groups there were significantly more MDD cases. Religion has often been reported to be an important coping mechanism with a positive influence on mental health (Koenig 2009). Numerous studies have been conducted on the relation between religion and depressive disorder, of which the majority reported religious people to have significantly lower rates of depressive disorder or fewer depressive symptoms (Koenig 2009). The association between religion and MDD led to a nominally significant negative association between autozygosity and MDD. Without knowledge of the relationship between religion and autozygosity, and between religion and MDD, the significant association may have led to the hypothesis that inbreeding protects against MDD (i.e., that recessive alleles unmasked by ROH are protective and an important part of the genetic architecture of MDD). This could be interpreted as a result of selection against the inability to develop MDD. This would be in line with the analytical rumination hypothesis which poses that MDD is an evolved response to complex problems, which functions by focusing the limited cognitive processing recourses on the analysis of the problems in the individuals life (Andrews and Thomson Jr 2009). However, after including religion as a covariate, MDD did not show a significant association with ROHs, while religion still contributed significantly to Froh variation. This suggests that the relation between autozygosity and MDD is a consequence of a stratification artifact.

The North-South PC contributed most significantly to Froh variation in all regressions. This was no surprise, as the Dutch North-South cline significantly correlates with genome-wide homozygosity (F), making the stratification captured by the North-South PC also well detectable by Froh. This correlation is likely due to a serial founder effect that is also visible in the European North-South cline that correlates highly (r = .66) with the Dutch North-South cline (Abdellaoui et al. 2013). Unlike Froh, F does not require a minimum amount of consecutive homozygous SNPs, and thus is able to capture much shorter (hence older) ROHs. Given that the serial founder effect captured by the North-South PC is expected to have occurred in more ancient times (during the European South-North expansions), we would expect a higher correlation between PC1 and F than between PC1 and Froh, which is indeed what we observe (rPC1,F = .245, p < .001; rPC1,Froh = .082, p < .001).

Genome-wide ROH mapping analyses did not reveal any genomic regions that were significantly more homozygous in any religious group, or in MDD cases or controls. This was not unexpected, as there was no reason to assume that past religious assortment was based on specific genomic regions, and there was no association between Froh and MDD.

A larger meta-analysis also found no significant relationship between autozygosity (Froh/ROHs) and MDD (9,238 MDD cases and 9,521 controls, including a subsample of the current study genotyped on a different microarray), and observed inconsistent directions of effect between the datasets (Power et al. 2013). The study included nine datasets from 5 countries (1 UK, 2 Australian, 3 German, 2 US, and 1 Dutch dataset), and the direction of the effects were consistent across countries (higher Froh protective for MDD: Australia, Netherlands, and US; lower Froh protective for MDD: UK and Germany). This suggests that there may be similar demographic/social factors associated with both autozygosity and MDD in other populations as well. In-depth analyses similar to those in the present study are needed to further explore this hypothesis in other populations.

Differences in autozygosity between social groups can unveil additional dimensions of stratification within populations. It shows in the Netherlands how recent secularization can have genetic consequences in a relatively small country. This can confound studies on traits associated with the stratifying factor, even when correcting for PCs reflecting ancestry and geographic factors. To detect effect sizes seen from known inbreeding studies in outbred populations, larger sample sizes than that of the current dataset are needed (~12,000–65,000) (Keller et al. 2012; Keller et al. 2011). The effects of within population differences as observed in the current study however are well detectable with the current sample size. It is crucial to the investigation of the effects of inbreeding on the well-being of offspring to take social factors into account that are predictive for both parental relatedness and the trait under investigation. Considering the sensitivity of Froh for social stratification not detected by PCAs, we also encourage to consider accounting for these effects in GWASs.

Acknowledgements

Funding was obtained from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO: MagW/ZonMW grants 904-61-090, 985-10-002,904-61-193,480-04-004, 400-05-717, Addiction-31160008 Middelgroot-911-09-032, Spinozapremie 56-464-14192, Geestkracht program grant 10-000-1002), Center for Medical Systems Biology (CSMB, NWO Genomics), NBIC/BioAssist/RK(2008.024), Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI –NL, 184.021.007), the VU University’s Institute for Health and Care Research (EMGO+) and Neuroscience Campus Amsterdam (NCA), the European Science Foundation (ESF, EU/QLRT-2001-01254), the European Community's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013), ENGAGE (HEALTH-F4-2007-201413); the European Science Council (ERC Advanced, 230374), Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (NIMH U24 MH068457-06), the Avera Institute for Human Genetics, Sioux Falls, South Dakota (USA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01D0042157-01A). Part of the genotyping was funded by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) of the Foundation for the US National Institutes of Health, the (NIMH, MH081802) and by the Grand Opportunity grants 1RC2MH089951-01 and 1RC2 MH089995-01 from the NIMH. AA was supported by CSMB/NCA. Statistical analyses were carried out on the Genetic Cluster Computer (http://www.geneticcluster.org), which is financially supported by the Netherlands Scientific Organization (NWO 480-05-003), the Dutch Brain Foundation, and the department of psychology and education of the VU University Amsterdam.

References

- Abdellaoui A, Hottenga JJ, de Knijff P, Nivard MG, Xiao X, Scheet P, Brooks A, Ehli EA, Hu Y, Davies GE, Hudziak JJ, Sullivan PF, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Willemsen G, de Geus EJ, Penninx BWJH, Boomsma DI. Population Structure, Migration, and Diversifying Selection in the Netherlands. Eur J Hum Genet Advance online publication. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alford JR, Hatemi PK, Hibbing JR, Martin NG, Eaves LJ. The politics of mate choice. J Pol. 2011;73(2):362–379. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews PW, Thomson JA., Jr The bright side of being blue: depression as an adaptation for analyzing complex problems. Psychol Rev. 2009;116(3):620. doi: 10.1037/a0016242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beekink E, Liefbroer AC, van Poppel F. Changes in choice of spouse as an indicator of a society in a state of transition: Woerden, 1830–1930. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung. 1998:231–253. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC, van Baal GCM, Koopmans JR. A religious upbringing reduces the influence of genetic factors on disinhibition: Evidence for interaction between genotype and environment on personality. Twin Res Hum Genet. 1999;2(02):115–125. doi: 10.1375/136905299320565988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC, Vink JM, Stubbe JH, Distel MA, Hottenga JJ, Posthuma D, van Beijsterveldt TCEM, Hudziak JJ, Bartels M. Netherlands Twin Register: from twins to twin families. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9(6):849–857. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, Willemsen G, Sullivan PF, Heutink P, Meijer P, Sondervan D, Kluft C, Smit G, Nolen WA, Zitman FG. Genome-wide association of major depression: description of samples for the GAIN Major Depressive Disorder Study: NTR and NESDA biobank projects. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(3):335–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braam AW, Hein E, Deeg DJH, Twisk JWR, Beekman ATF, van Tilburg W. Religious involvement and 6-year course of depressive symptoms in older Dutch citizens: results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. J Aging Health. 2004;16(4):467–489. doi: 10.1177/0898264304265765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broek Kvd. 6PP database: http://www.d-centralize.nl/projects/6pp/downloads/ 2012

- CBS. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand, April 2012. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D, Willis JH. The genetics of inbreeding depression. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(11):783–796. doi: 10.1038/nrg2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dein S, Cook CCH, Powell A, Eagger S. Religion, spirituality and mental health. The Psychiatrist. 2010;34(2):63–64. [Google Scholar]

- DeRose MA, Roff DA. A comparison of inbreeding depression in life-history and morphological traits in animals. Evolution. 1999:1288–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb04541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri Kaart van Nederland met godsdienstverhoudingen per gemeente bij de volkstelling van 1849. [date retrieved: January 15, 2013];Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Donk WBHJ, Jonkers A, Kronjee G, Plum R. Geloven in het publieke domein: verkenningen van een dubbele transformatie. Amsterdam University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haber M, Gauguier D, Youhanna S, Patterson N, Moorjani P, Botigué LR, Platt DE, Matisoo-Smith E, Soria-Hernanz DF, Wells RS. Genome-Wide Diversity in the Levant Reveals Recent Structuring by Culture. PloS Genet. 2013;9(2):e1003316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howrigan DP, Simonson MA, Keller MC. Detecting autozygosity through runs of homozygosity: A comparison of three autozygosity detection algorithms. BMC Genomics. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Simonson MA, Ripke S, Neale BM, Gejman PV, Howrigan DP, Lee SH, Lencz T, Levinson DF, Sullivan PF. Runs of Homozygosity Implicate Autozygosity as a Schizophrenia Risk Factor. PloS Genet. 2012;8(4):e1002656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Visscher PM, Goddard ME. Quantification of inbreeding due to distant ancestors and its detection using dense single nucleotide polymorphism data. Genetics. 2011;189(1):237–249. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Marston L, McManus S, Brugha T, Meltzer H, Bebbington P. Religion, spirituality and mental health: results from a national study of English households. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knippenberg H. De religieuze kaart van Nederland: omvang en geografische spreiding van de godsdienstige gezindten vanaf de Reformatie tot heden. Uitgeverij Van Gorcum. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: A review. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):283–291. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok J. Vrijt daar je zijt”: huwelijk en partnerkeuze in Zeeland tussen 1830 en 1950. In: Mandemakers K, Hoogerhuis en O, de Klerk A, editors. Over Zeeuwse mensen Demografische en sociale ontwikkelingen in Zeeland in de negentiende en begin twintigste eeuw Themanummer Zeeland. 1998. pp. 7131–7143. [Google Scholar]

- Lencz T, Lambert C, DeRosse P, Burdick KE, Morgan TV, Kane JM, Kucherlapati R, Malhotra AK. Runs of homozygosity reveal highly penetrant recessive loci in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(50):19942–19947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710021104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubke GH, Hottenga JJ, Walters R, Laurin C, de Geus EJ, Willemsen G, Smit JH, Middeldorp CM, Penninx BW, Vink JM. Estimating the genetic variance of major depressive disorder due to all single nucleotide polymorphisms. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(8):707–709. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelis M, Navarro-Mateu F, Murray R, Selten J-P, Van Os J. Urbanization and psychosis: a study of 1942–1978 birth cohorts in The Netherlands. Psychological medicine. 1998;28(4):871–879. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan R, Leutenegger AL, Abdel-Rahman R, Franklin CS, Pericic M, Barac-Lauc L, Smolej-Narancic N, Janicijevic B, Polasek O, Tenesa A. Runs of homozygosity in European populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83(3):359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Sage M, Tenke CE, Weissman MM. Religiosity and major depression in adults at high risk: a ten-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):89–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton TJ, Absher D, Feldman MW, Myers RM, Rosenberg NA, Li JZ. Genomic patterns of homozygosity in worldwide human populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(2):275–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, Beekman ATF, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Nolen WA, Spinhoven P, Cuijpers P, De Jong PJ, Van Marwijk HWJ, Assendelft WJJ. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Meth Psych Res. 2008;17(3):121–140. doi: 10.1002/mpr.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman A. Geografische en confessionele invloeden bij de huwelijkskeuze in Nederland. Stenfert Kroese. 1951 [Google Scholar]

- Power RA, Keller MC, Ripke S, Abdellaoui A, Wray NR, Sullivan PF, Group MPW, Breen G. A Recessive Genetic Model and Runs of Homozygosity in Major Depressive Disorder. Submitted. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38(8):904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, De Bakker PIW, Daly MJ. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripke S, Lewis CM, Lin DYU, Wray N. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheet P, Ehli EA, Xiao X, van Beijsterveldt CE, Abdellaoui A, Althoff RR, Hottenga JJ, Willemsen G, Nelson KA, Huizenga PE. Twins, Tissue, and Time: An Assessment of SNPs and CNVs. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2012;15(6):737. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seybold KS, Hill PC. The role of religion and spirituality in mental and physical health. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001;10(1):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O'Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(8):537–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1552–1562. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist K, Frank G, Sundquist J. Urbanisation and incidence of psychosis and depression Follow-up study of 4.4 million women and men in Sweden. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184(4):293–298. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpiech ZA, Xu J, Pemberton TJ, Peng W, Zöllner S, Rosenberg NA, Li JZ. Long Runs of Homozygosity Are Enriched for Deleterious Variation. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiessen D, Gregg B. Human assortative mating and genetic equilibrium: An evolutionary perspective. Ethol Sociobiol. 1980;1(2):111–140. [Google Scholar]

- Van Os J. Does the urban environment cause psychosis? The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;184(4):287–288. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Klohnen EC, Casillas A, Nus Simms E, Haig J, Berry DS. Match makers and deal breakers: Analyses of assortative mating in newlywed couples. J Pers. 2004;72(5):1029–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. World Health Organisation: Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 2.1. [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen G, Boomsma DI. Religious upbringing and neuroticism in Dutch twin families. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10(2):327–333. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemsen G, de Geus EJC, Bartels M, van Beijsterveldt CEMT, Brooks AI, Estourgie-van Burk GF, Fugman DA, Hoekstra C, Hottenga JJ, Kluft K. The Netherlands Twin Register biobank: a resource for genetic epidemiological studies. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2010;13(3):231. doi: 10.1375/twin.13.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray N, Pergadia M, Blackwood D, Penninx B, Gordon S, Nyholt D, Ripke S, Macintyre D, McGhee K, Maclean A. Genome-wide association study of major depressive disorder: new results, meta-analysis, and lessons learned. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;17(1):36–48. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]