Summary

One of the most straightforward approaches to making novel biological discoveries is the forward genetic screen. The time is ripe for forward genetic screens in the mouse, since the mouse genome is sequenced but the function of many of the genes remains unknown. Today, with careful planning, such screens are within the reach of even small individual labs. In this chapter we first discuss the types of screens in existence, as well as how to design a screen to recover mutations that are relevant to the interests of a lab. We then describe how to create mutations using the chemical N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU), including a detailed injection protocol. Next, we outline breeding schemes to establish mutant lines for each type of screen. Finally, we explain how to map mutations using recombination and how to ensure that a particular mutation causes a phenotype. Our goal is to make forward genetics in the mouse accessible to any lab with the desire to do it.

Keywords: ENU, mutagenesis, mutant, phenotype-driven screen

1. Introduction

Recent years have brought an explosion of whole-genome sequencing in a wide variety of organisms. From this explosion, comparative genomics has emerged as a powerful tool for shedding light on a range of biological processes, with the potential to reveal much about human variation, development, and disease. However, comparative genomics will not fulfill its potential until we have a more complete understanding of the functions of the individual genes in these genomes, so they can be related back to their human counterparts. For example, the function of a third of the genes in the mouse genome is still completely unknown. Of the approximately 26,000 genes in the mouse genome, 8,154 (31%) genes have no functional annotation (1). Perhaps more remarkably, 17,904 (68%) genes in the mouse genome have no mutant alleles (1). Several international projects are underway to produce null alleles of every gene in the mouse genome, so that gene function can be inferred from the resulting phenotype (2, 3). Such a “reverse genetics” approach will provide valuable resources to the mouse community and fill many gaps in our knowledge. Complementary to this approach is forward genetics, which begins with a mutant phenotype in a biological process of interest, and then asks what gene is disrupted to produce that particular phenotype. Forward genetic screens, therefore, can give us an unbiased view of a biological process from which novel discoveries can flow. Furthermore, the nature of the allele obtained in a mutagenesis screen can tell us a great deal about a particular protein's role in a specific process in a way that deletion of the protein cannot. Finally, another benefit of alleles created via chemical mutagenesis is that they tend to mimic human disease alleles (4).

Reverse genetics has become the preferred method for individual labs studying specific mammalian genes. Recently, however, a growing number of labs are interested in forward genetics, largely for two reasons. First, the availability of the mouse genome sequence has made positional cloning much more straightforward, due in part to a denser set of markers that allows one to more easily narrow down the region in which a mutation lies. Further, we now know exactly how many genes are in any particular region. This information, combined with available gene expression data, makes it easier to prioritize which genes to sequence to find the causative mutation. Second, mutagenesis screens in the mouse have the unique ability to impartially reveal a collection of genes involved in a biological process of interest. In the current genomics era, where the focus is shifting from understanding single gene products to understanding how networks of gene products interact and influence one another, forward genetics is a particularly apt and powerful tool.

How practical is it for an individual lab to perform a forward genetic screen in the mouse? General concerns are time, breeding space required, and cost. Although the time from mutagenization to the establishment of mutant lines is about one year, much of this is passive time spent waiting for males to recover fertility after mutagenization and setting up crosses. The active screening time is four or five months. The amount of breeding space required reflects this passive/active time pattern, with a long period of housing relatively few mice, followed by the active screening phase, when a burst of mice are produced (Fig. 11.1). Once mutant lines are established, active positional cloning takes several months to about a year to complete. However, next-generation resequencing technology holds promise that we will further accelerate of this step, as longer portions of a chromosome can be sequenced for less time and cost. Overall, it is quite feasible for an individual lab to carry out a mutagenesis screen, and the goal of this chapter is to provide the reader with practical considerations and instructions to do just that.

Figure 11.1.

Approximate breeding space required per month in a generic yearlong screen for recessive mutations.

2. Materials

Mice: 7- to 8-week-old males of the desired strain for mutagenization (see section 3.2).

N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)

95% ethanol: Make fresh each time.

Phosphate/citrate buffer: 0.1 M dibasic sodium phosphate, 0.05 M sodium citrate, adjust to pH 5.0 with phosphoric acid. Make fresh each time.

- ENU inactivating solution: Use one of the following:

- 0.1 M potassium hydroxide

- Alkaline sodium thiosulfate: 0.1 M sodium hydroxide, 1.3 M sodium thiosulfate

Syringes/needles: For ENU dilution: 18-gauge needles, 10 mL syringes, 30 to 50 mL syringes. For ENU injections: 25-gauge needles and 1 mL syringes.

Squirt bottles

Waste containers: Hazardous waste plastic bags, container for deactivated ENU, sharps disposal box

Personal protective equipment for handling ENU: Disposable gowns, masks, gloves

Disposable bench paper to line hood during ENU injections

3. Methods

3.1. Designing a screen

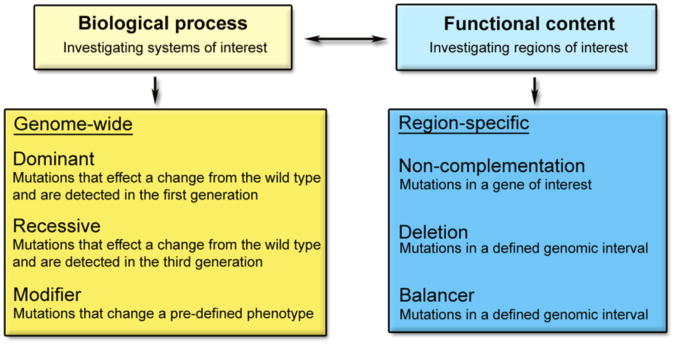

The initial consideration is a critical one: how to design a screen to recover mutations that suit the interests and goals of the lab? One way to approach this question is to first determine whether you are interested in a general biological process or a particular gene or region of the genome (Fig. 11.2). Those interested in a general biological process are best served by a genome-wide screen, since it is likely that numerous genes scattered throughout the genome control the process of interest. Those more interested in the functional content of a given region of the genome, or in generating an allelic series of a particular gene, will find a region-specific screen more appropriate. Another consideration is the time it will take to map and clone causative mutations once the screening is complete. In a genome-wide screen, the recovered mutations can be at any position on any chromosome. Positional cloning takes several months to a year to complete, because one must generate enough embryos to allow up to 1,500 opportunities for recombination, design primers to find polymorphic markers, and sequence. Since region-specific screens are limited to a defined portion of the genome, finding the causative mutation is greatly simplified, reducing the overall time and cost. We will examine several classes of both genome-wide and region-specific genetic screens below.

Figure 11.2.

Classes of genome-wide and region-specific forward genetic screens. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nat Rev Genet (33), copyright 2005.

Having defined screening criteria is another important factor to consider when designing a screen, for ease of phenotype identification and reproducibility. For example, our lab recently completed a screen for recessive mutations that affect embryonic development. We broadly examined embryos for morphological abnormalities, but for consistency we chose nine key features to score, such as brain lobes, eyes, and pharyngeal arches. Increasingly complex assays can lead to lengthy or slow screening. For instance, screens that include criteria such as serum analysis or behavioral assays may limit the number of mutant lines that can be screened. Each lab must weigh for itself the relative costs and benefits of including extra steps in a screen.

Genome-wide screens

Genome-wide screens can be designed to recover mutations that create either dominant or recessive alleles. Dominant alleles cause a phenotype that is observed in the heterozygous state, either because two normal alleles are required for normal function of the gene (haploinsufficiency), because the mutant allele disrupts the function of the normal allele (dominant negative), or because the mutant allele has new or increased activity (gain-of-function). One purely practical reason to screen for dominant alleles is that they can be recovered in the fewest number of crosses, thereby reducing time and cost (see section 3.3). Another possible rationale for performing a dominant screen is to model a human disease condition with a dominant mode of transmission (for examples, see 5).

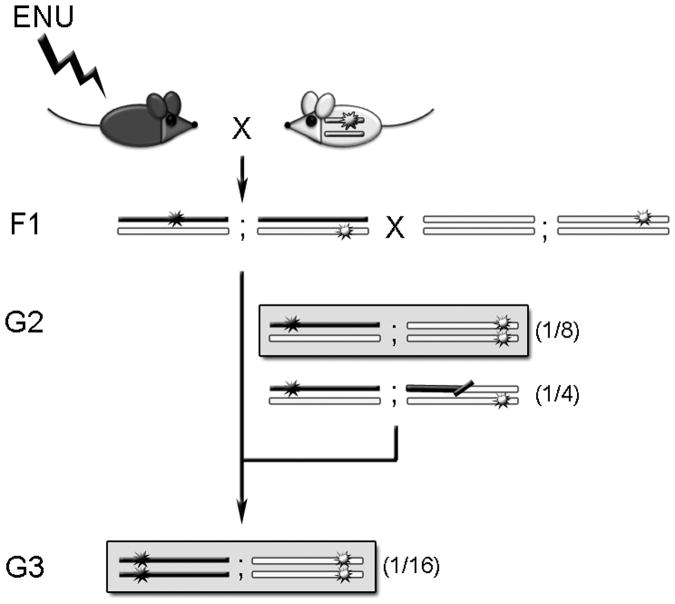

Recessive alleles can be partial or total loss-of-function, and both alleles must be mutant to produce a phenotype. Therefore, three crosses are required to recover mutations that create recessive alleles (Fig. 11.3). The additional breeding time can be justified, however, since it is easier to infer normal gene function from recessive alleles, as they are generally loss-of-function.

Figure 11.3.

Crossing scheme for dominant (upper grey box) or recessive (lower grey box) mutant alleles. In this and all subsequent figures, chromosomes from the mutagenized black mouse are represented as black bars; chromosomes from the white mouse are represented as white bars. Additionally, in all figures stars represent mutant alleles.

The final class of genome-wide screen is the modifier screen: recovering new genes that suppress or enhance a phenotype of interest. Modifier screens are performed when at least one gene is known to be necessary for a biological process of interest, and the goal is to discover other genes in the same pathway or same process. Modifier screens can be designed to recover dominant or recessive alleles, as above. They can also be performed with known alleles that are not viable in the homozygous state, although the crossing scheme is more involved (Fig. 11.4).

Figure 11.4.

Crossing scheme for dominant (upper grey box) or recessive (lower grey box) modifier alleles. In this crossing scheme the allele to be modified (in the white mouse) is assumed to be homozygous lethal or sterile. The half-black/half-white chromosome in the second generation indicates that either allele is acceptable in this cross.

Region-specific screens

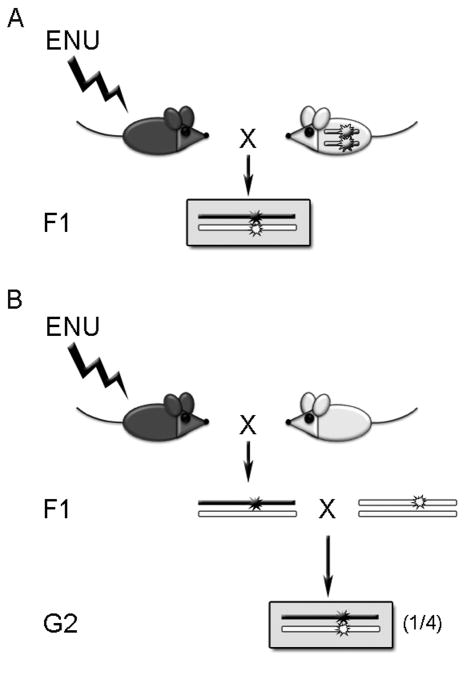

The narrowest type of region-specific screen is the non-complementation screen. The purpose of a non-complementation screen is to find new alleles of a gene of interest, because mutations in different protein domains can reveal much about the function of those domains, and/or can help to define specific interactions with other proteins. In a non-complementation screen, one crosses an animal carrying a known mutation in a particular allele with an animal carrying random mutations (Fig. 11.5). If the progeny of such a cross exhibit the mutant phenotype of the known allele, the newly mutagenized allele is said to “fail to complement” the original allele. It is important to note that since mutations are induced randomly in the genome, a failure to complement can be either allelic or non-allelic; if it is allelic, then the mutation will be revealed through sequencing the gene in the new mutant background. If it is non-allelic, the mutation must be mapped via meiotic recombination (see section 3.4).

Figure 11.5.

Non-complementation crossing scheme. (A) The allele to be tested (in white mouse) is viable and fertile as a homozygote. (B) The allele to be tested (in white mouse) is lethal or sterile as a homozygote.

Deletion screens incorporate mouse strains with deletions in known portions of their genome. A number of deletion strains are available in the mouse, with about half of the chromosomes having at least one “deletion complex,” or collection of overlapping deletions (Table 11.1). The first seven deletion complexes were generated by irradiating or chemically mutating mice, and then crossing them to mice with visible markers. In this way deletions could be located to the region surrounding the visible marker (specific locus test, (6). These initial deletion complexes each contain many available mouse strains with overlapping deletions (Table 11.1, grey rows). More recently, deletion complexes are created in genomic areas of interest using embryonic stem cells (ES cells). Deletions are generated in ES cells through irradiation or through Cre-loxP-mediated recombination, and then mice bearing the deletions are produced from the ES cells, when possible (Table 11.1, white rows) (7-10). In addition to simplifying the mapping process, another practical reason to perform a deletion screen is that recessive mutations can be recovered in fewer crosses than in a genome-wide recessive screen (Fig. 11.6). The only caveat is that the deletion strain used in the screen must be viable as a heterozygote (i.e., cannot be haploinsufficient), a fact not yet known for the deletions that only exist as ES cells.

Table 11.1.

Mouse chromosomal deletion complexes. The number of available mouse lines per deletion complex is estimated based on the primary literature and current information from Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI). If no mouse lines have been established, but embryonic stem (ES) cell lines have been generated, they are listed. The deletion complexes are named after the loci that served as the deletion focal point. Rows colored dark grey indicate deletion complexes identified in the specific locus test (6). The light grey row is a deletion complex that includes two closely linked loci identified in the specific locus test.

| Chr | Deletion Complex | No. mouse/cell lines | Mode of generation | Total span of nested deletions, if known | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Non-agouti (a) | ∼17 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of mouse/germ cells | (1, 6, 34, 35) | |

| 2 | Notch1 | 10 cell lines | ES cell: recombination-mediated deletion | 6.2-7.7 cM (10.4 Mb) | (36) |

| 4 | Brown (Tyrp1b) | ∼35 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of mouse/germ cells | ∼21 Mb | (1, 6, 37−39) |

| 5 | Hdh, Dpp6, Gabrb1 | 10 mouse lines | ES cell: X ray irradiation | 40 cM | (40) |

| 7 | Albino (Tyrc) | ∼55 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of mouse/germ cells | 6-11 cM for 29 of the lines | (1, 6, 41, 42) |

| 7 | Pink-eyed dilution (p) | ∼65 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of whole mouse | (1, 6, 43-45) | |

| 9 | Dilute (Myo5ad) | ∼16 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of mouse/germ cells | (1, 6, 46, 47) | |

| 9 | Short ear (Bmp5se) | ∼4 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of mouse/germ cells | (1, 6, 47, 48) | |

| 9 | Dilute and Short ear (d se) | ∼29 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of mouse/germ cells | (1, 6, 47) | |

| 9 | Ncam | 28 cell lines | ES cell: X & UV irradiation | 28 cM | (8) |

| 11 | Hsd17b1 [Del(11)Brd] | 8 mouse lines | ES cell: recombination-mediated deletion | 8 Mb | (49) |

| 14 | Piebald (Ednrbs) | 20 mouse lines | Mixed (chemical & radiation) of mouse/germ cells | 15.7-18 cM | (1, 6, 50, 51) |

| 15 | Sox10 | 2 mouse lines | ES cell: X ray irradiation | 577 kb | (52) |

| 15 | Oc90 | 2 mouse lines | ES cell: X ray irradiation | 658 kb-5Mb | (52) |

| 15 | Cpt1b | 192 cell lines | ES cell: X ray irradiation | (52) | |

| 17 | D17Aus9 | 3-7 mouse lines | ES cell: X ray irradiation | <1-7 cM | (9) |

| 17 | Sod2, D17Leh94 | 8 mouse lines | ES cell: X ray irradiation | ∼14 Mb | (53) |

| X | Hprt | 4 cell lines | ES cell: recombination-mediated deletion | ∼1 cM | (49) |

| X | Hprt | 9 cell lines | ES cell: X & UV irradiation | 1-3 cM | (8) |

| X | Hprt | 2 mouse lines | ES cell: X ray irradiation | 200-700 kb | (54) |

Figure 11.6.

Deletion screen crossing scheme. The chromosome with a gap indicates the region that is deleted. Mutant alleles are recovered in the second generation (grey box).

The final region-specific screen is the balancer screen, modeled after successful screens performed in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. A “balancer chromosome” is one that contains inversions to prevent recombination with its homolog, plus a dominant marker, so that animals carrying it can be recognized. Balancer chromosomes may contain recessive lethal mutations as well. They are called “balancers” because they prevent any lethal or sterile mutations on the homologous chromosome from being removed from a population (i.e. they maintain heterozygosity). Screens performed with balancer chromosomes therefore have several advantages: the visible marker allows one to identify and select the G2 and G3 mice that are potentially carrying mutations, in contrast to performing blind crosses, as one must in genome-wide screens (Fig. 11.7). In addition, the ability to genotype using visible markers is not only faster and cheaper than PCR-based methods, but provides an advantage in determining whether the mutation segregates to the balancer region. Finally, if the mutant phenotype is recessive lethal or sterile, the line can be more easily maintained, since it is balanced. One drawback of performing a balancer screen is that currently there are not yet many balancer mouse strains available (see Table 11.2). However, they can be generated using recombination in ES cells (7, 11, 12). Furthermore, more G0 males may need to be injected, because only half of the F1 males will be subsequently used (those carrying the balancer, see Fig. 11.7). Finally, when screening for embryonic lethal phenotypes it is best to use a balancer that is viable when homozygous, to prevent confusion about the cause of lethality

Figure 11.7.

Balancer screen crossing scheme. The white bar with double-sided arrows indicates the balanced chromosome. In the first generation, F1 mice are crossed to mice carrying the inversion in trans to a WT chromosome marked with a dominant visible mutation (dotted bar with black circle). Mutant alleles are recovered in the third generation (grey box).

Table 11.2.

Mouse balancer strains. Strains that are viable as homozygotes are indicated.

| Chr | Name | Dominant marker phenotype (gene) | Recessive lethal? (gene, if known) | Mode of generation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Inv(4)Brd1Mit281-Mit51 | Coat color (Tyrosinase & K14-agouti) | No | Cre-loxP mediated recombination | (55) |

| 4 | Inv(4)Brd1Mit117-Mit281 | Coat color (Tyrosinase & K14-agouti) | No | Cre-loxP mediated recombination | (55) |

| 5 | Rump white (Rw) | Coat color (Kit receptor tyrosine kinase) | Yes | Irradiation | (56, 57) |

| 10 | Steel panda (Slpan) | Coat color (Kit ligand) | No | Irradiation | (58) |

| 11 | Inv(11)Trp53-Wnt3 | Coat color (K14-agouti) | Yes (Wnt3) | Cre-loxP mediated recombination | (12) |

| 11 | Inv(11)Wnt3-D11Mit69 | Coat color (K14-agouti) | Yes (Wnt3) | Cre-loxP mediated recombination | (59) |

| 11 | Inv(11)Trp53-EgfR | Coat color (K14-agouti) | No | Cre-loxP mediated recombination | (59) |

| 15 | In(15)2R1 | Short, hairy ears (Eh) | Yes | Chemical mutagenesis or irradiation | (60) |

| 15 | In(15)21Rk | Coat color (K14-agouti) | Yes | Modification of line derived from chemical mutagenesis or irradiation | (61) |

3.2. Mutagenization

There are several methods to mutagenize the mouse genome: chemicals like N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) and chlorambucil, irradiation with X-rays or gamma rays, and transposons such as sleeping beauty (6, 13-17). For the purposes of this chapter we focus on the most widely used method, the chemical ENU. ENU is a powerful mutagen. Depending on the strain of mouse and the dose given, ENU induces a point mutation every 0.5-16 Mb throughout the genome (18-22), which is about 100 times higher than the spontaneous mutation rate per generation in humans (23). Further, ENU primarily affects spermatogonial stem cells, so that one male mouse will produce multiple clones of mutated sperm after completion of spermatogenesis (24). In addition to its efficient nature, another advantage of ENU is the variety of protein altercations that can result from this form of mutagenization. Since ENU is an alkylating agent that induces point mutations, nonsense (10%), missense (63%), splicing (26%), and “make-sense” (1%) mutations can all occur (reviewed in 25-27). Therefore, in addition to null alleles, other alleles will also be generated, including hypomorphs, hypermorphs, and dominant-negative alleles. This ability to generate an allelic series is one of the great strengths of forward genetics.

Inbred strains and ENU dose

One of the first practical considerations is which strain of mice to mutagenize. A popular choice is C57BL/6J, because the effective dose of ENU is well defined and the genome is sequenced for this strain, facilitating future mapping and analysis portions of the screen. Nevertheless, with the increased density of genetic markers and cheaper and more advanced resequencing technologies, choosing other strains has become feasible. Such advancements allow more flexibility in screen design, for instance by enabling one to incorporate visible markers (such as GFP) that may only be available on a particular genetic background. When choosing the strain of mice to mutagenize, it is important to note that ENU affects inbred strains differently (Table 11.3). In all strains, ENU initially depletes all spermatogonia from the testes, leading to a period of sterility from which some males never recover. In addition, some mice may die during the sterile period due to somatic mutations that lead to cancer or increase susceptibility to pathogens. The length of the sterile period and the deaths vary with ENU dosage and each inbred strain; some strains (like BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J) can tolerate a relatively high dose, whereas others (like FVB/N) are very sensitive to ENU. For successful mutagenesis, one must balance the highest possible mutation load with the lowest rates of sterility and death.

Table 11.3.

| Inbred mouse strain | Recommended Dose (mg/kg)* | No. days of sterility | Percent regained fertility |

|---|---|---|---|

| A/J | 3 × 90 | 74-113 | 90% (n=10) |

| BALB/cJ | 3 × 100 | 89-154 | 83% (n=6) |

| BTBR/N | 1 × 150-200 | 70-210 | 50-83% (ND) |

| C3He/J | 3 × 85 | 96-148 | 70% (n=10) |

| C3HeB/FeJ | 3 × 75 | 89-142 | 90% (n=10) |

| C57BL/6J | 3 × 100 | 90-105 | 80% (n=10) |

The doses are recommended based on the least amount of death and shortest period of sterility. For details and alternate doses, see the original papers. ND=no data.

Thanks to careful analysis and experimentation by Justice et al., 2000 and Weber et al., 2000 (28, 29), the optimal ENU dose for various inbred strains can be estimated; we provide a summary in Table 11.3. As indicated in Table 11.3, a fractionated series of injections at weekly intervals is generally more effective than one single large injection, since a series maximizes the mutagenic effect and minimizes animal lethality (30). For instance, rather than a single dose of 300 mg/kg, inject 3 doses of 100 mg/kg at weekly intervals (written as 3 × 100 mg/kg).

Number of mice to inject

The number of males to inject depends on how many genes in the genome one wishes to survey. Each F1 animal is estimated to be heterozygous for about 20-30 gene-inactivating mutations, based on the specific locus test and data from other mutagenesis screens (6, 31). In a genome-wide screen, 100 F1 lines will therefore interrogate 2,000-3,000 genes, about 8-12% of the genome. Since ENU mutagenizes spermatogonial stem cells leading to clones of mutant sperm, no more than eight F1 animals should come from any particular G0 father, to avoid rescreening the same mutation. In theory, for 100 F1 lines, a minimum of 12-13 G0 males should be injected. However, since some percentage of the G0 males will either fail to recovery fertility, or die (or both), it is good practice to inject about three times the minimum number of males. For example, in a recently completed genetic screen in our lab, we injected 50 C57/BL6 males with 3 × 100 mg/kg ENU. After 10-12 weeks, about half the males had died before recovering fertility. From the remaining G0 males, we recovered 122 F1 males.

ENU injection protocol (modified from 32)

ENU is carcinogenic and must be handled with extreme care. Most institutions require an IACUC safety approval justification and common FAQs on ENU. ENU can be obtained as 1 g of powder in a light-protected ISOPAC container. ENU is sensitive to light, humidity, and pH. For this reason, it should be stored at −20°C in the dark until use and then diluted no more than three hours before injection.

Prior to injection

Complete all institutional IACUC safety approval procedures (varies from institution to institution).

Order male mice of the strain to be injected so that they will be 7 to 8 weeks old at the time of injection, keeping in mind that they will need at least one week to adjust to their new environment after arrival.

Day of injection

Make all solutions and gather all materials (see above).

-

Weigh all males to be injected and calculate the amount of ENU to inject per mouse, based on the following formula:For example, if you want a final concentration of 100 mg/kg ENU in a 20 g C57BL/6J mouse:

- Dissolve and dilute ENU to 10 mg/ml (see Note 4.1):

- Inject 10 mL of 95% ethanol into the ISPOAC container. Swirl gently to dissolve. When dissolved, ENU is a clear yellow liquid.

- Vent ISOPAC with an 18-gauge needle. Inject 90 mL of phosphate/citrate buffer into container.

Inject mice: an experienced person familiar with intraperitoneal injections should inject each mouse with the proper volume (determined from the formula above) following standard procedures.

After injection, the mice will become uncoordinated from the alcohol and lose consciousness for a short time, usually about 20 minutes. During this time they should be monitored to ensure they recover consciousness.

Deactivate and dispose of ENU: ENU should be completely deactivated. Since it has a short half-life under alkaline conditions, use one of the two inactivating solutions given above to thoroughly rinse all materials that came in contact with ENU. In our experience it is best to minimize handling the materials on the day of injection; therefore, we leave all materials in the hood with the light on overnight to further ensure that the ENU is deactivated. Prominent signs should be displayed on the hood and room in which ENU is deactivating, alerting unknowing staff and coworkers to the presence of ENU.

After injection

After the last weekly injection, let males recover for 2 to 3 weeks.

A good indication that the mutagenesis was successful is sterile males. To ensure that males are sterile, mate them with females (at this time the females can be any strain and can likely be used for other experiments if the males are indeed sterile). Males are sterile if mating plugs are observed but the females do not become pregnant

Starting 2 to 3 weeks before the males are expected to regain fertility (see Table 11.3), set males up with 1 or 2 females of the desired strain (usually different from the G0 strain, for mapping purposes, see below).

3.3. Breeding crosses and establishment of mutant lines

Once the G0 males have recovered fertility, the more active phase of the screening process begins: breeding crosses to screen for mutant phenotypes and establish mutant lines. The class of screen dictates the series of crosses to perform; each crossing scheme is outlined below.

Genome-wide screen: dominant mutations (Fig. 11.3)

1st cross

Cross the mutagenized G0 male to one or two females of a different (preferably inbred) strain. It is advantageous to cross the G0 males to females of a different strain, as polymorphic markers between the strains permit straightforward mutation mapping (see section 3.4). The number of polymorphisms between strains varies, so this should be taken into account when choosing the crossing strain (Table 11.4).

Table 11.4.

The number of informative SNPs between common inbred strains. The polymorphic SNPs are derived from a low density whole genome SNP panel of 768 SNPs. From the Mutation Mapping and Developmental Analysis Project (MMDAP), with permission from J. L. Moran and D. R. Beier (personal communication).

| C57BL/ 6J | 129×1/ SvJ | BALB/ cJ | C3H/ HeJ | DBA/2J | FVB/NJ | A/J | CBA/J | C57BL/ 10J | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6J | 508 | 497 | 598 | 555 | 539 | 581 | 562 | 68 | |

| 129×1/SvJ | 315 | 333 | 365 | 316 | 367 | 313 | 455 | ||

| BALB/cJ | 233 | 323 | 285 | 203 | 262 | 448 | |||

| C3H/HeJ | 241 | 294 | 226 | 111 | 552 | ||||

| DBA/2J | 323 | 325 | 235 | 518 | |||||

| FVB/NJ | 274 | 281 | 492 | ||||||

| A/J | 276 | 547 | |||||||

| CBA/J | 514 |

Dominant mutations will be recovered in the first generation (F1) (upper grey box in Fig. 11.3). Since the mutations occur randomly in the sperm of the G0 male, each F1 animal represents a unique suite of mutations and is thus considered a “line”. However, since the G0 spermatogonial stem cells are mutated, it is best to screen no more than eight F1 animals from any one G0 male, to avoid rescreening the same mutation. Collect F1 animals and screen for the phenotype of interest. Once F1 animals with an interesting phenotype are identified, they must be maintained as separate lines. If the dominant mutation is viable and fertile, it is simply a matter of breeding the F1 animal to the same inbred strain chosen in cross #1.

Genome-wide screen: recessive mutations (Fig. 11.3)

1st cross

Same as above. Collect eight F1 males per G0 male and allow them to come to breeding age. Discard F1 females.

2nd cross

Breed each F1 male individually to two wild-type females of the same inbred strain used in the 1st cross. Collect G2 females only and allow them to come to breeding age; discard G2 males to save mouse room space and cost (new G2 males can be obtained later, if needed, to establish lines of interest).

3rd cross

Back-cross G2 females to their F1 fathers. Mate at least six G2 females to each F1 male. When a phenotype has been observed in at least two G3 animals from two separate G2 females, it is likely genetic. To maintain the line, collect G2 males and mate them to their sibling G2 females to determine whether the G2 male is a carrier; carrier males are then kept for subsequent breeding and analysis (see section 3.4).

Alternative 3rd cross

A theoretical drawback to backcrossing the G2 females to F1 males is that it places reproductive strain on the F1 male, since he will be needed to produce many litters. In our experience, however, we have not encountered problems with this. Nonetheless, an alternative to backcrossing is intercrossing G2 male and female siblings. This method has the advantage that G2 carrier males are immediately identified; a drawback is that both G2 males and females must be weaned from the second cross, above, increasing mouse room space and cost.

Genome-wide screen dominant or recessive modifier (Fig. 11.4)

The breeding scheme presented here assumes that the mutation to be modified is not viable in the homozygous state (white mouse in Fig. 11.4).

1st cross

Cross G0 males to females of a different strain who are heterozygous for the allele to be modified. Collect F1 animals (no more than eight per G0 male, as above) and allow them to come to breeding age.

2nd cross

Cross F1 animals to animals of the same strain as the females crossed to G0 males, above. Dominant modifiers will be seen in G2 animals; collect and screen for enhancement or suppression of the phenotype of interest.

3rd cross

Back-cross G2 females to their F1 fathers. Recessive modifiers will be seen in G3 animals; collect and screen for enhancement or suppression of the phenotype of interest.

Region-specific screen: non-complementation (Fig. 11.5)

If the starting allele is homozygous viable and fertile (white mouse in Fig. 11.5A)

1st cross

Cross G0 males with females of a different inbred strain who are homozygous for the allele of interest. Collect F1 animals (no more than eight per G0 male, as above) and screen them for failure to complement the mutation (i.e., exhibit the same phenotype as animals homozygous for the starting allele).

If the starting allele is homozygous lethal or sterile (white mouse in Fig. 11.5B)

1st cross

Cross G0 males with wild-type females of the same genetic background as those containing the allele of interest. Collect F1 animals (no more than eight per G0 male, as above) and allow them to come to breeding age.

2nd cross

Cross F1 animals to animals that are heterozygous for the allele of interest. Screen the resulting G2 progeny for a failure to complement the allele of interest. As mentioned above, a failure to complement can be either allelic or non-allelic, and this can be determined through direct sequencing of the gene in the new mutant background.

Region-specific screen: deletion screen for lethal or sterile recessive mutations (Fig. 11.6)

1st cross

Cross G0 males to wild-type females from the same genetic background as the deletion strain used in the 2nd cross, below. Collect F1 animals and allow them to come to breeding age.

2nd cross

Cross F1 animals to animals hemizygous for a deleted region of interest. Any recessive mutations that occur in trans to the deleted region will be observable in the G2 progeny.

Region-specific screen: using balancers (Fig. 11.7)

1st cross

Cross G0 males to females of a different inbred strain who are heterozygous for a balancer chromosome. Collect F1 animals carrying the balancer chromosome (one-half of the F1 progeny) and allow them to come to breeding age.

2nd cross

Cross F1 animals carrying the balancer to animals carrying the balancer in trans to a wild-type chromosome marked with a dominant visible marker that is distinct from the visible marker on the balancer chromosome. Collect G2 animals that are heterozygous for the newly mutated chromosome over the balancer chromosome (can be distinguished based on visible markers). Discard the rest of the progeny.

3rd cross

Back-cross G2 animals to their F1 parents. The G3 animals can again be distinguished by their visible markers. If a G3 animal is not carrying a balancer chromosome, then it is homozygous for the newly mutated chromosome. If such animals exhibit a phenotype, then the mutation lies in the balanced region of the genome. However, if a G3 animal has a phenotype but is heterozygous for the balancer, then the mutation lies outside the balanced region, elsewhere in the genome.

3.4. Analysis and cloning

The excitement of establishing a new mutant line with an interesting phenotype may only be surpassed by discovering the underlying genetic change that causes the phenotype. Traditionally, there are three main steps to accomplish this goal: recombination mapping to narrow down the genomic interval in which a mutation lies, sequencing candidate genes in this genomic interval, and confirming that a particular mutation is indeed responsible for the observed phenotype.

Mapping based on recombination

Since mice from one inbred strain (“x”) are mutagenized, and then crossed to mice of another inbred strain (“y”), the F1 generation is 50% x and 50% y. In the process of establishing and maintaining mutant lines, mice are continually crossed to the non-mutagenized (y) background, all the while selecting for the mutation. Over several generations, therefore, the genome of the mutant lines will largely be of the y background, while the region surrounding the mutation will be of the x background. The premise of recombination mapping is that the causative mutation will be linked to the x background, which can be distinguished by polymorphisms that differ between the x and y backgrounds. There are two main classes of polymorphisms used in recombination mapping: simple sequence length polymorphisms (SSLPs), which are short repeated segments that differ in length between inbred strains, and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Both classes can be used to create polymorphic “markers.” SSLP markers are created by designing PCR primers around the SSLP, so that the size of the PCR product differs between two strains. SNP markers can be created by finding SNPs that create restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs), also detectable by PCR. In addition, SNPs can be genotyped directly using array-based SNP panels (see below).

The first step of recombination mapping is to determine on which chromosome the mutation lies. This is achieved by performing a genome-wide scan using polymorphic markers that are spaced at regular intervals throughout the genome at low density. Several commercially available SNP panels have been designed for this purpose. For example, Illumina's mouse Low Density (LD) and Medium Density (MD) Linkage Panels contain 377 and 1,449 SNPs, respectively, spaced across the entire mouse genome. DNA from affected (mutant) animals is obtained, and the SNPs contained in the linkage panels are genotyped to determine which chromosome has the largest cluster of DNA from the mutagenized background. The required starting amount of DNA is low (750 ng-1.5 μg), and can be obtained from tissue from a single animal. To detect linkage, DNA from eight or nine affected animals should be SNP genotyped.

The next step is high-resolution mapping, which is essentially the same process, but using markers that are more closely spaced. In the course of mapping their own mutations, several groups have created polymorphic markers and made them available to the public (see online resources, below). You should first determine whether any of the available markers are appropriate for your use. If there are no informative markers in the region of interest, then markers will need to be created. Step-by-step instructions are available from the Sloan-Kettering site, below. Use the markers to genotype both affected and non-affected animals from each line. Since affected animals are known to carry the mutation, and the mutation lies in a region of mutagenized background DNA (e.g., “x”), informative animals will be recombinants that have wild-type DNA (e.g., “y”) adjacent to mutagenized DNA. Since the portion of the chromosome containing wild-type DNA cannot contain the mutation, that portion can be ruled out. As more affected recombinant animals are genotyped, longer portions of the chromosome are eliminated. Conversely, non-affected recombinant animals are used to rule out portions of the chromosome that are homozygous for mutagenized DNA (for recessive alleles). It is important to note that, if there are any issues with penetrance of the phenotype one can easily be misled by apparently non-affected animals and may want to exclude them from analysis.

Below is a partial list of online resources to locate or design appropriate markers:

Sloan-Kettering Mouse Project website

MarkerBase: Provides a list of available Sloan-Kettering Institute (SKI) developed makers, a searchable database of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) markers, and a guide to create your own.

Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI)

Integrated Whitehead/MIT Linkage and Physical maps: Provides a list of available MIT markers by chromosome: www.informatics.jax.org/reports/mitmap

- Strains, SNPs, and Polymorphisms

- SNP query: search for SNPs by strain, SNP attributes, genomic position, or associated genes.

- Search for RFLP or PCR-based polymorphisms by strain, locus symbol, or map position.

Ensembl genome browser

www.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/Info/Index

Browse for SNPs by chromosome (karyotype) or enter genomic location.

Genetic variation: resequencing data for nine inbred strains is compared with the C57BL/6J genomic sequence, and SNPs are highlighted.

Sequencing

Once the genomic interval in which a mutation lies has been narrowed sufficiently, the next step is to sequence candidate gene(s) in the interval. A number of factors influence the decision of when and what to begin sequencing. One consideration is whether there are additional polymorphisms that could potentially narrow the interval further. However, the chance of obtaining recombinant animals decreases as the interval is narrowed. Perhaps the best indicator that the time to sequence has come is that there are a manageable number of genes in the interval, which may or may not be correlated with the physical size of the interval. What is “manageable” depends on the investigator, but larger collections of genes can be prioritized for sequencing based on expression data or any available phenotypic data. In addition, since ENU causes mutations in exons and splice sites in the vast majority of cases, sequencing entire genes is not necessary.

The availability of next-generation resequencing technologies is poised to change how investigators perceive what is a manageable number of genes to sequence. It is becoming practical to sequence very long portions of a chromosome at a time, and for less money. This technology may drastically alter the balance of time spent mapping versus sequencing, to the point that, ultimately, one may only need to know which chromosome contains the mutation before beginning to sequence.

Confirmation

How do you know that a mutation actually causes the observed phenotype? Direct evidence includes genetic rescue or complementation. Genetic rescue occurs when a wild-type copy of the gene is introduced into the mutant background, and the mutant phenotype is no longer observed. Although direct, this method is time-consuming because it involves creating transgenic mice. The other direct method is a complementation analysis, which involves creating mice that have one copy of your mutant allele and one copy of a known mutant allele in the suspected gene. If the mutant phenotype is seen in such an animal, then your allele fails to complement the phenotype and is an allele of the suspected gene. While this is faster than genetic rescue, it depends on the availability of mutant alleles in the gene of interest. There can also be indirect evidence that a mutation causes the observed phenotype, including disruption of gene expression, protein production, protein activity, or cellular/tissue localization. Other indirect evidence may be that the observed mutant phenotype is similar to other alleles of the suspected gene, or is similar to the mutant phenotype of genes in the same pathway.

4. Notes

4.1 ENU injections: To spec or not to spec?

The concentration of ENU can be determined by spectrophotometry after dilution in phosphate/citrate buffer. This is the best way to be absolutely certain about the exact amount of ENU you are injecting into the mice, since it is possible that there is not exactly one gram of ENU in the container provided by Sigma. Problems can result if the amount of ENU injected is too high (e.g., all the G0 males die or fail to recover fertility) or too low (e.g., failure to obtain relevant mutant lines). If you are experiencing one of these problems despite having taken the inbred mouse strain into consideration, you may need to spec the ENU. A good protocol can be found in (32). However, in our experience we have found that handling the ENU as little as possible is best, and following the strain guidelines and injecting a sufficient number of males yields good results.

4.2 Screening

It may be hard to tell if a particular phenotype is truly genetic, or just a random phenomenon. A good rule of thumb is that the phenotype should be seen in multiple animals from separate litters, at a frequency of approximately 25% (for recessive alleles). If screening for embryonic lethal mutations, the G2 females will be dissected to view the G3 embryos. To avoid an overwhelming number of dissections on any one day, it is best to mate only two G2 females to the F1 male at a time. As mating plugs are observed, place the pregnant females in a separate cage and replenish the mating cage with new G2 females.

Table 1.

Recommended dose of ENU for different inbred mouse strains, modified from Justice et al 2000 and Weber et al 2000.

| Inbred mouse strain | Recommended Dose (mg/kg) | No. days of sterility | Percent regained fertility |

|---|---|---|---|

| A/J | 3 ×90 | 74-113 | 90%(n=10) |

| BALB/cJ | 3 × 100 | 89-154 | 83% (n=6) |

| BTBR/N | 1 × 150-200 | 70-210 | 50-83% (ND) |

| C3He/J | 3 × 85 | 96-148 | 70%(n=10) |

| C3HeB/FeJ | 3 × 75 | 89-142 | 90%(n=10) |

| C57BL/6J | 3 × 100 | 90-105 | 80%(n=10) |

| FVB/N | 1 × 150 | 147 | 75% (n=4) |

The doses are recommended based on the least amount of death and shortest period of sterility. For details and alternate doses, see the original papers.

References

- 1.Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Blake JA. The Mouse Genome Database (MGD): mouse biology and model systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D724–728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins FS, Finnell RH, Rossant J, Wurst W. A new partner for the international knockout mouse consortium. Cell. 2007;129:235. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FS, Rossant J, Wurst W Consortium, T. I. M. K. A mouse for all reasons. Cell. 2007;128:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien TP, Frankel WN. Moving forward with chemical mutagenesis in the mouse. J Physiol. 2004;554:13–21. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D514–517. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell WL, Kelly EM, Hunsicker PR, Bangham JW, Maddux SC, Phipps EL. Specific-locus test shows ethylnitrosourea to be the most potent mutagen in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:5818–5819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills AA, Bradley A. From mouse to man: generating megabase chromosome rearrangements. Trends Genet. 2001;17:331–339. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02321-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas JW, LaMantia C, Magnuson T. X-ray-induced mutations in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1114–1119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.You Y, Bergstrom R, Klemm M, Lederman B, Nelson H, Ticknor C, Jaenisch R, Schimenti J. Chromosomal deletion complexes in mice by radiation of embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 1997;15:285–288. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You Y, Browning VL, Schimenti JC. Generation of radiation-induced deletion complexes in the mouse genome using embryonic stem cells. Methods. 1997;13:409–421. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hentges KE, Justice MJ. Checks and balancers: balancer chromosomes to facilitate genome annotation. Trends Genet. 2004;20:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng B, Sage M, Cai WW, Thompson DM, Tavsanli BC, Cheah YC, Bradley A. Engineering a mouse balancer chromosome. Nat Genet. 1999;22:375–378. doi: 10.1038/11949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flaherty L, Messer A, Russell LB, Rinchik EM. Chlorambucil-induced mutations in mice recovered in homozygotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2859–2863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russell LB, Hunsicker PR, Cacheiro NL, Bangham JW, Russell WL, Shelby MD. Chlorambucil effectively induces deletion mutations in mouse germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:3704–3708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell LB, Russell WL. Frequency and nature of specific-locus mutations induced in female mice by radiations and chemicals: a review. Mutat Res. 1992;296:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(92)90035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell WL. X-ray-induced mutations in mice. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1951;16:327–336. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1951.016.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda J, Keng VW, Horie K. Germline mutagenesis mediated by Sleeping Beauty transposon system in mice. Genome Biol. 2007;8(1):S14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-s1-s14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beier DR. Sequence-based analysis of mutagenized mice. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:594–597. doi: 10.1007/s003350010113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Yee D, Dains K, Chatterjee A, Cavalcoli J, Schneider E, Om J, Woychik RP, Magnuson T. Genotype-based screen for ENU-induced mutations in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2000;24:314–317. doi: 10.1038/73557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coghill EL, Hugill A, Parkinson N, Davison C, Glenister P, Clements S, Hunter J, Cox RD, Brown SD. A gene-driven approach to the identification of ENU mutants in the mouse. Nat Genet. 2002;30:255–256. doi: 10.1038/ng847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Concepcion D, Seburn KL, Wen G, Frankel WN, Hamilton BA. Mutation rate and predicted phenotypic target sizes in ethylnitrosourea-treated mice. Genetics. 2004;168:953–959. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.029843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gondo Y, Fukumura R, Murata T, Makino S. Next-generation gene targeting in the mouse for functional genomics. BMB Rep. 2009;42:315–323. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2009.42.6.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nachman MW, Crowell SL. Estimate of the mutation rate per nucleotide in humans. Genetics. 2000;156:297–304. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell LB. Effects of male germ-cell stage on the frequency, nature, and spectrum of induced specific-locus mutations in the mouse. Genetica. 2004;122:25–36. doi: 10.1007/s10709-004-1443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balling R. ENU mutagenesis: analyzing gene function in mice. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2001;2:463–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Justice MJ, Noveroske JK, Weber JS, Zheng B, Bradley A. Mouse ENU mutagenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1955–1963. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.10.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noveroske JK, Weber JS, Justice MJ. The mutagenic action of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea in the mouse. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:478–483. doi: 10.1007/s003350010093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Justice MJ, Carpenter DA, Favor J, Neuhauser-Klaus A, Hrabe de Angelis M, Soewarto D, Moser A, Cordes S, Miller D, Chapman V, Weber JS, Rinchik EM, Hunsicker PR, Russell WL, Bode VC. Effects of ENU dosage on mouse strains. Mamm Genome. 2000;11:484–488. doi: 10.1007/s003350010094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber JS, Salinger A, Justice MJ. Optimal N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) doses for inbred mouse strains. Genesis. 2000;26:230–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell WL, Hunsicker PR, Carpenter DA, Cornett CV, Guinn GM. Effect of dose fractionation on the ethylnitrosourea induction of specific-locus mutations in mouse spermatogonia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:3592–3593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson L, Ching YH, Farias M, Hartford SA, Howell G, Shao H, Bucan M, Schimenti JC. Random mutagenesis of proximal mouse chromosome 5 uncovers predominantly embryonic lethal mutations. Genome Res. 2005;15:1095–1105. doi: 10.1101/gr.3826505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salinger AP, Justice MJ. Mouse Mutagenesis Using N-Ethyl-N-Nitrosourea (ENU) Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2008 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kile BT, Hilton DJ. The art and design of genetic screens: mouse. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:557–567. doi: 10.1038/nrg1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barsh GS, Epstein CJ. Physical and genetic characterization of a 75-kilobase deletion associated with al, a recessive lethal allele at the mouse agouti locus. Genetics. 1989;121:811–818. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.4.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller MW, Duhl DM, Vrieling H, Cordes SP, Ollmann MM, Winkes BM, Barsh GS. Cloning of the mouse agouti gene predicts a secreted protein ubiquitously expressed in mice carrying the lethal yellow mutation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:454–467. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LePage DF, Church DM, Millie E, Hassold TJ, Conlon RA. Rapid generation of nested chromosomal deletions on mouse chromosome 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10471–10476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett DC, Huszar D, Laipis PJ, Jaenisch R, Jackson IJ. Phenotypic rescue of mutant brown melanocytes by a retrovirus carrying a wild-type tyrosinase-related protein gene. Development. 1990;110:471–475. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.2.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smyth IM, Wilming L, Lee AW, Taylor MS, Gautier P, Barlow K, Wallis J, Martin S, Glithero R, Phillimore B, Pelan S, Andrew R, Holt K, Taylor R, McLaren S, Burton J, Bailey J, Sims S, Squares J, Plumb B, Joy A, Gibson R, Gilbert J, Hart E, Laird G, Loveland J, Mudge J, Steward C, Swarbreck D, Harrow J, North P, Leaves N, Greystrong J, Coppola M, Manjunath S, Campbell M, Smith M, Strachan G, Tofts C, Boal E, Cobley V, Hunter G, Kimberley C, Thomas D, Cave-Berry L, Weston P, Botcherby MR, White S, Edgar R, Cross SH, Irvani M, Hummerich H, Simpson EH, Johnson D, Hunsicker PR, Little PF, Hubbard T, Campbell RD, Rogers J, Jackson IJ. Genomic anatomy of the Tyrp1 (brown) deletion complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3704–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600199103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rinchik EM. Molecular genetics of the brown (b)-locus region of mouse chromosome 4. II. Complementation analyses of lethal brown deletions. Genetics. 1994;137:855–865. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schimenti JC, Libby BJ, Bergstrom RA, Wilson LA, Naf D, Tarantino LM, Alavizadeh A, Lengeling A, Bucan M. Interdigitated deletion complexes on mouse chromosome 5 induced by irradiation of embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 2000;10:1043–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rikke BA, Johnson DK, Johnson TE. Murine albino-deletion complex: high-resolution microsatellite map and genetically anchored YAC framework map. Genetics. 1997;147:787–799. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.2.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shibahara S, Okinaga S, Tomita Y, Takeda A, Yamamoto H, Sato M, Takeuchi T. A point mutation in the tyrosinase gene of BALB/c albino mouse causing the cysteine----serine substitution at position 85. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:455–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardner JM, Nakatsu Y, Gondo Y, Lee S, Lyon MF, King RA, Brilliant MH. The mouse pink-eyed dilution gene: association with human Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Science. 1992;257:1121–1124. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson DK, Stubbs LJ, Culiat CT, Montgomery CS, Russell LB, Rinchik EM. Molecular analysis of 36 mutations at the mouse pink-eyed dilution (p) locus. Genetics. 1995;141:1563–1571. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell LB, Montgomery CS, Cacheiro NL, Johnson DK. Complementation analyses for 45 mutations encompassing the pink-eyed dilution (p) locus of the mouse. Genetics. 1995;141:1547–1562. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mercer JA, Seperack PK, Strobel MC, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Novel myosin heavy chain encoded by murine dilute coat colour locus. Nature. 1991;349:709–713. doi: 10.1038/349709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rinchik EM, Russell LB, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Molecular genetic analysis of the dilute-short ear (d-se) region of the mouse. Genetics. 1986;112:321–342. doi: 10.1093/genetics/112.2.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kingsley DM, Bland AE, Grubber JM, Marker PC, Russell LB, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. The mouse short ear skeletal morphogenesis locus is associated with defects in a bone morphogenetic member of the TGF beta superfamily. Cell. 1992;71:399–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90510-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su H, Wang X, Bradley A. Nested chromosomal deletions induced with retroviral vectors in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;24:92–95. doi: 10.1038/71756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roix JJ, Hagge-Greenberg A, Bissonnette DM, Rodick S, Russell LB, O'Brien TP. Molecular and functional mapping of the piebald deletion complex on mouse chromosome 14. Genetics. 2001;157:803–815. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.2.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hosoda K, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Baynash AG, Cheung JC, Giaid A, Yanagisawa M. Targeted and natural (piebald-lethal) mutations of endothelin-B receptor gene produce megacolon associated with spotted coat color in mice. Cell. 1994;79:1267–1276. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chick WS, Mentzer SE, Carpenter DA, Rinchik EM, Johnson D, You Y. X-ray-induced deletion complexes in embryonic stem cells on mouse chromosome 15. Mamm Genome. 2005;16:661–671. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Browning VL, Bergstrom RA, Daigle S, Schimenti JC. A haplolethal locus uncovered by deletions in the mouse T complex. Genetics. 2002;160:675–682. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.2.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kushi A, Edamura K, Noguchi M, Akiyama K, Nishi Y, Sasai H. Generation of mutant mice with large chromosomal deletion by use of irradiated ES cells--analysis of large deletion around hprt locus of ES cell. Mamm Genome. 1998;9:269–273. doi: 10.1007/s003359900747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nishijima I, Mills A, Qi Y, Mills M, Bradley A. Two new balancer chromosomes on mouse chromosome 4 to facilitate functional annotation of human chromosome 1p. Genesis. 2003;36:142–148. doi: 10.1002/gene.10207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hough RB, Lengeling A, Bedian V, Lo C, Bucan M. Rump white inversion in the mouse disrupts dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein 6 and causes dysregulation of Kit expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13800–13805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stephenson DA, Lee KH, Nagle DL, Yen CH, Morrow A, Miller D, Chapman VM, Bucan M. Mouse rump-white mutation associated with an inversion of chromosome 5. Mamm Genome. 1994;5:342–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00356552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bedell MA, Brannan CI, Evans EP, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Donovan PJ. DNA rearrangements located over 100 kb 5′ of the Steel (Sl)-coding region in Steel-panda and Steel-contrasted mice deregulate Sl expression and cause female sterility by disrupting ovarian follicle development. Genes Dev. 1995;9:455–470. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klysik J, Dinh C, Bradley A. Two new mouse chromosome 11 balancers. Genomics. 2004;83:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davisson MT, Roderick TH, Akeson EC, Hawes NL, Sweet HO. The hairy ears (Eh) mutation is closely associated with a chromosomal rearrangement in mouse chromosome 15. Genet Res. 1990;56:167–178. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300035266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chick WS, Mentzer SE, Carpenter DA, Rinchik EM, You Y. Modification of an existing chromosomal inversion to engineer a balancer for mouse chromosome 15. Genetics. 2004;167:889–895. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.026468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]