Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine if thioredoxin-1 (Trx1) mediates the cardioprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in a model of ischemic-induced heart failure.

Approach/Results

Mice with a cardiac-specific overexpression of a dominant negative mutant of Trx1 (Tg-DN-Trx1) and wild-type littermates were subjected to ischemic-induced heart failure. Treatment with H2S as sodium sulfide (Na2S) not only increased the gene and protein expression of Trx1 in the absence of ischemia, but also augmented the heart failure-induced increase in both. Wild-type mice treated with Na2S experienced less left ventricular (LV) dilatation, improved LV function, and less cardiac hypertrophy after the induction of heart failure. In contrast, Na2S therapy failed to improve any of these parameters in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice. Studies aimed at evaluating the underlying cardioprotective mechanisms found that Na2S therapy inhibited heart failure-induced apoptosis signaling kinase-1 (ASK1) signaling and nuclear export of histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) in a Trx1-dependent manner.

Conclusions

These findings provide novel information that the upregulation of Trx1 by Na2S therapy in the setting of heart failure sets into motion events, such as the inhibition of ASK1 signaling and HDAC4 nuclear export, which ultimately leads to the attenuation of LV remodeling.

In response to myocardial injury, the geometry, mass, volume, and function of the left ventricle (LV) change during a process referred to as ventricular remodeling. Initially, this process is considered to be adaptive. However, in response to continuous stimuli following events such as myocardial infarction, LV remodeling becomes maladaptive leading to the development of heart failure.1 Moreover, the morphological and functional changes that accompany LV remodeling serve as predictors of morbidity and mortality.2 Therefore, it is necessary to elucidate cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie the development of heart failure so that pharmacotherapies designed to coincide with the standard means of care can be implemented to improve the prognosis of patients suffering from this debilitating disease3.

In this regard, therapeutic strategies aimed at increasing the levels of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) have come to be a focus of interest given their ability to exert cytoprotective effects in various models of injury. In the heart, treatment with exogenous H2S or modulation of the endogenous production of H2S through the cardiac-specific overexpression of the H2S-generating enzyme, cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), promotes cardioprotection against acute myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury and heart failure.4,5 In contrast, the pharmacological inhibition or genetic deficiency of CSE results in an exacerbation of myocardial injury.6,7 These and other studies demonstrate that H2S utilizes a variety of effects to counter ischemic injury, including its ability to attenuate oxidative stress, inhibit apoptosis, and reduce inflammation.7 While these studies provide important insights into the cardioprotective actions of H2S, they have not fully investigated the cellular mechanisms that underlie these cytoprotective effects.

Thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) is an oxidoreductase enzyme that acts as an antioxidant by facilitating the reduction of other proteins by cysteine thiol-disulfide exchange.8 Through its redox activity Trx1 regulates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1 (ASK1), nuclear factor κB, Ras, and Akt.9 Patients with acute coronary syndrome and dilated cardiomyopathy show elevated serum levels of Trx1 suggesting a possible association between Trx1 and the severity of heart failure.10 Experimental studies demonstrate that Trx1 plays a pro-survival role in response to myocardial injury. This is attributed to its ability to reduce cardiac hypertrophy in models of heart failure11,12 and to reduce apoptosis in models of heart failure13 and I/R injury.14 Therefore, Trx1 is an ideal cellular target for impeding the progression of heart failure.

H2S has previously been shown to increase the protein expression of Trx1 following a single injection.4 Based on this evidence and the evidence that Trx1 plays a protective role in the heart, one can speculate that Trx1 contributes to the cardioprotective mechanisms of H2S. Therefore, a major goal of this study was to determine if Trx1 mediates the cardioprotective effects of H2S in a model of ischemic-induced heart failure.

Results

Na2S Treatment Limited the Extent of Myocardial Injury Following Heart Failure

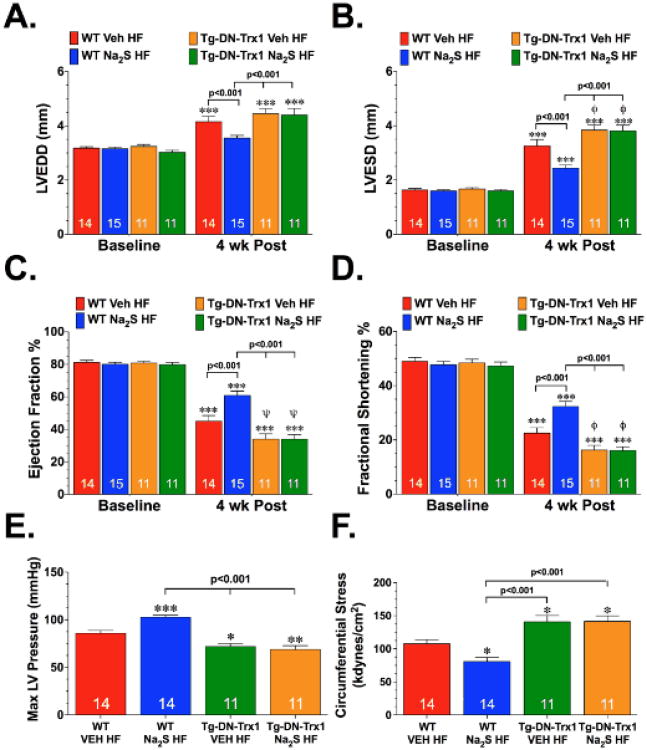

Initial experiments were conducted to investigate the extent of myocardial injury and the effects of H2S in the ischemic heart failure model. For these experiments, mice were subjected to 60 minutes of LCA ischemia followed by 4 weeks of reperfusion. H2S, administered in the form of Na2S (100 μg/kg), or vehicle was administered at reperfusion and then for the first 7 days of reperfusion. Heart failure increased LVEDD and LVESD in both groups (Figure 1A-B; p<0.01 vs. Baseline). However, the increase in LV dimensions was attenuated in mice treated with Na2S (WT Na2S HF) compared to vehicle-treated mice (WT Veh HF; p<0.001). Following heart failure, LV EF and LV FS decreased in both groups (Figure 1C-D, p<0.001 vs. Baseline). Na2S treatment, however, significantly improved LV function (p<0.001 vs. WT Veh HF). Along with the improvements in LV dimensions and function, Na2S-treated mice displayed better contractility and relaxation following the induction of heart failure when compared to the vehicle-treated mice, as evidenced by the improvements in LV dP/dt max, dP/dt min and the relaxation time constant Tau (Supplemental Figure I), as well as Max LV pressure, and circumferential stress (Figure 1E-F; p<0.05 vs. WT Veh HF).

Figure 1.

Na2S therapy failed to improve LV structure and function in Thioredoxin-1 dominant-negative transgenic mice following heart failure. (A) Left Ventricular End Diastolic Diameter (LVEDD), (B) Left Ventricular End Systolic Diameter (LVESD), (C) LV Ejection Fraction, and (D) LV Fractional Shortening (E) Max LV Pressure and (F) Circumferential Stress for wild-type (WT) and Trx1 dominant negative transgenic (Tg-DN-Trx1) mice treated with vehicle (WT Veh HF and Tg-DN-Trx1 Veh HF) or Na2S (100 μg/kg for 7 days; WT Na2S HF and Tg-DN-Trx1 Na2S HF) 4 weeks after myocardial ischemia. Numbers inside bars indicate sample size. Values are means ±SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. Baseline or WT Veh HF. (x003C6)p<0.05 and (x003C8)p<0.01 vs. WT Veh HF.

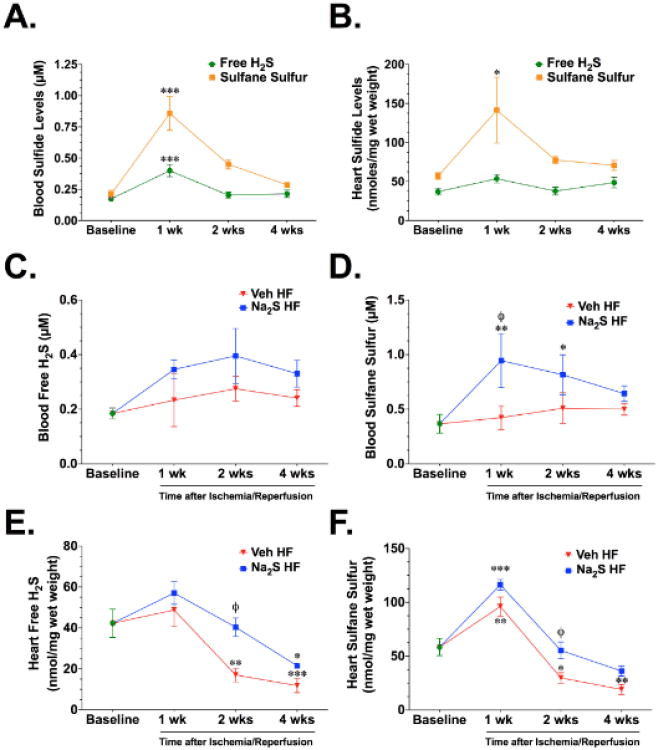

Additional experiments were then conducted to determine the circulating and cardiac levels of sulfide following treatment with Na2S in the presence and absence of heart failure. For the first set of experiments, mice were treated with Na2S for 7 days (daily tail vein injections) and then different groups were sacrificed at 1 week, 2 weeks, and 4 weeks after the start of treatment. At the end of the treatment period (1 week), free H2S and sulfane sulfur (bound sulfide) levels were significantly increased in the blood when compared to baseline levels (Figure 2A). However, these levels returned to baseline levels by 1 week after the end of the treatment period (2 week time point). In the heart, Na2S treatment did not significantly increase free H2S levels at any time point investigated (Figure 2B). Cardiac sulfane sulfur levels were increased at the end of the treatment period and then declined to baseline levels by 1 week after the end treatment (2 week time point). Experiments then were conducted to evaluate the circulating and cardiac levels of sulfide in the setting of heart failure. For these experiments, mice were subjected to heart failure and Na2S treatment as described above. Different groups were then sacrificed at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after reperfusion. Circulating levels of free H2S and sulfane sulfur were not altered in the Veh HF group at any time point investigated (Figure 2C-D). In contrast, free H2S levels trended (p=NS) to be higher in the Na2S group and sulfane levels were significantly higher at both 1 week (p<0.05 vs. Veh HF and p<0.01 vs. Baseline) and 2 weeks (p<0.05 vs. Baseline) of reperfusion. In the heart, free H2S and sulfane sulfur levels rose slightly higher than baseline levels at 1 week of reperfusion in the Veh HF group before significantly falling to levels below baseline at both 2 weeks and 4 weeks of reperfusion (Figure 2E-F). Cardiac levels of sulfide in the Na2S HF group displayed similar trends with the Veh HF group. However, the levels in the Na2S HF group were higher than the Veh HF levels at all time points evaluated, especially at 2 weeks after reperfusion (p<0.05 vs. Veh HF).

Figure 2.

Circulating and cardiac sulfide levels after Na2S therapy. (A) Circulating and (B) cardiac free H2S and sulfane sulfur (bound sulfide) levels from groups of mice treated with Na2S for 7 days and sacrificed at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after the start of treatment. (C-D) Circulating and (E-F) cardiac free H2S and sulfane sulfur levels from vehicle-treated (Veh HF) and Na2S-treated (Na2S HF) mice from 1 to 4 weeks of reperfusion. Values are means ±SEM for 6-8 mice per group. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. Baseline. (x003C6)p<0.05 vs. WT Veh HF.

Na2S Therapy Increases the Gene and Protein Expression of Trx1

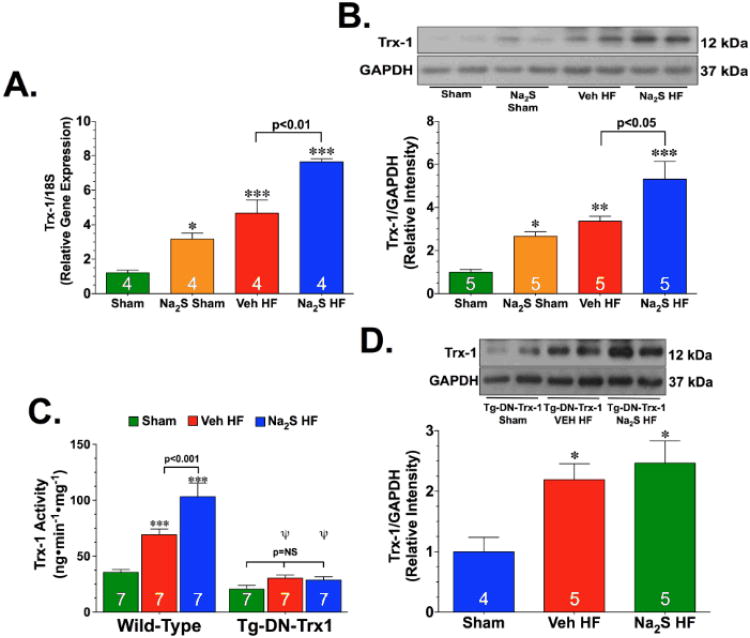

One of the potential mechanisms by which it is hypothesized that Na2S provides cytoprotection during the development of heart failure is through an increase in Trx1 signaling. Therefore, experiments were conducted to evaluate if Na2S therapy altered the expression of Trx1 in the setting of heart failure. For these experiments, mice were divided into sham or heart failure groups. The mice in the sham groups were administered vehicle (Sham) or Na2S (Na2S Sham) for 7 days. The mice in the heart failure groups were subjected to myocardial I/R injury and received either vehicle (Veh HF) or Na2S (Na2S HF) at reperfusion and then daily for 7 days after reperfusion. Mice were then sacrificed at this time and the hearts were processed to evaluate changes in the gene and protein expression of Trx1. PCR analysis revealed an increase in the gene expression of Trx1 in the Na2S Sham mice (Figure 3A; p<0.05 vs. Sham). Heart failure also significantly increased the gene expression of Trx1 when compared to the sham hearts (p<0.001). Importantly, the Trx levels were found to be the highest in the hearts from the Na2S HF mice (p<0.001 vs. Sham and p<0.01 vs. Veh HF). Western blot analysis confirmed the increase in Trx1 protein levels with similar trends (Figure 3B). Additionally, Trx1 activity was significantly increased after heart failure in both groups (Figure 3C; p<0.001 vs. Sham). Again, Trx activity was found to be the highest in the hearts from the Na2S HF mice (p<0.01 vs. Veh HF).

Figure 3.

Na2S therapy augments heart failure-induced upregulation of thioredoxin 1 expression. (A) Relative gene expression, (B) representative immunoblots and densitometric analysis of the protein expression of cardiac thioredoxin 1 (Trx1) from wild-type (WT) mice, and (C) cardiac Trx1 activity from WT and Tg-DN-Trx1 mice. (D) Representative immunoblots and densitometric analysis of the protein expression of cardiac Trx1 from Tg-DN-Trx1 mice. Mice were divided into sham or heart failure groups. The sham groups were administered vehicle (Sham) or Na2S (Na2S Sham) for 7 days. The heart failure groups received either vehicle (Veh HF) or Na2S (Na2S HF) at reperfusion and then daily for 7 days after reperfusion. Values are means ±SEM. *p<0.01, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 vs. Sham. (x003C8)p<0.01 vs. WT Veh HF.

Na2S Therapy Failed to Attenuate the Development of Heart Failure Without Functional Trx1

Experiments were then conducted to investigate if Trx1 was critical for the cardioprotection afforded by Na2S therapy. Tg-DN-Trx1 mice were subjected to heart failure and Na2S treatment as described above. Echocardiography at 4 weeks of reperfusion revealed that heart failure significantly increased LVEDD and LVESD in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice receiving vehicle (Tg-DN-Trx1 Veh HF) or Na2S (Tg-DN-Trx1 Na2S HF) (Figure 1A-B; p<0.05 vs. Baseline). The increase in LVESD was significantly higher in both groups of Tg-DN-Trx1 mice when compared to the WT Veh HF group (p<0.05). Heart failure also reduced LV EF and LV FS both groups (Figure 1C-D; p<0.001 vs. Baseline). Again the decrease in both LV EF and LV FS was significantly lower in both groups of Tg-DN-Trx1 mice when compared to the WT Veh HF group (p<0.05). Importantly, Na2S therapy failed to reduce the dimensions or improve LV function in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice. The failure of Na2S therapy to attenuate the development of heart failure without functional Trx1 was further confirmed with hemodynamic measurements. Na2S therapy failed to improve any of these measurements in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice (Figure 1E-F and Supplemental Figure I).

The Tg-DN-Trx1 possesses a cardiac-specific overexpression of a dominant negative mutant of Trx1, which results in diminished activity of endogenous Trx.11 Because this is not a true knockout model, experiments were conducted to determine how heart failure and Na2S treatment affect the expression and activity of endogenous Trx1 in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice. First, using an antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-18215) that recognizes both human and mouse Trx1 and an antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (2298S) that only recognizes mouse and rat Trx1, it was determined the cardiac expression of endogenous Trx1 was similar between Tg-DN-Trx1 and WT mice (Supplemental Figure IIA-B). Heart failure significantly increased the expression of endogenous Trx1 in both groups of Tg-DN-Trx1 mice (Figure 3D, p<0.05 vs. Sham). The increase in expression was not as high as the increase observed in the WT mice and Na2S treatment did not further increase Trx1 levels in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice. Additionally, the activity of Trx1 was not increased in either group of mice following the induction of heart failure (Figure 3C). Together, this data suggests that heart failure does increase the expression of endogenous Trx1 in the Tg-DN-Trx1, but the activity of Trx1 does not change.

Na2S Therapy Failed to Decrease Cardiac Hypertrophy Without Functional Trx1

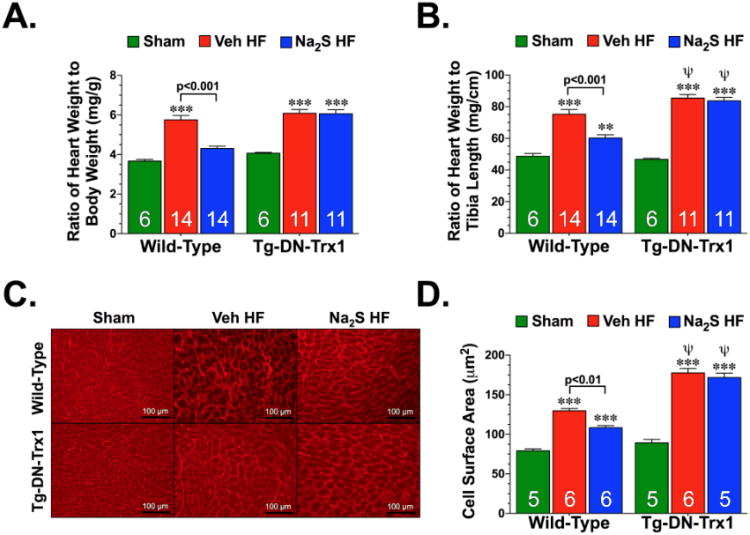

Cardiac hypertrophy was analyzed by determining heart weight to body weight ratios, heart weight to tibia length ratios, and myocardial cell surface area in both WT and Tg-DN-Trx1 mice (Figure 4). Analysis at 4 weeks of reperfusion revealed that heart failure significantly increased heart weight to body weight and heart weight to tibia length ratios, as well as myocardial cell surface area in the WT and Tg-DN-Trx1 mice receiving vehicle or Na2S treatment. When compared to the WT Veh HF group, the Tg-DN-Trx1 Veh HF and Tg-DN-Trx1 Na2S HF groups displayed more of an increase in cardiac hypertrophy based on the heart weight to tibia length ratios and myocardial cell surface area measurements (Figure 4B-D; p<0.01). Treatment with Na2S reduced cardiac hypertrophy in the WT mice, but failed to reduce hypertrophy in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice.

Figure 4.

Na2S therapy failed to improve cardiac hypertrophy without functional Trx1. (A) Ratios of heart to body weight (HW:BW) and (B) heart weight to tibia length (HW:TL) were used as a measure of cardiac hypertrophy in WT and Tg-DN-Trx1 mice 4 weeks after the induction of heart failure. (C) Representative photomicrographs of wheat germ agglutinin stained hearts from WT Sham, WT Veh HF, WT Na2S HF, Tg-DN-Trx1 Sham, Tg-DN-Trx1 Veh HF, and Tg-DN-Trx1 Na2S HF mice. (D) Summary of myocyte cell surface area measurements of wheat germ agglutinin stained hearts. Scale bar equals 100 μm. Values are means ±SEM. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. Sham. (x003C8)p<0.01 vs. WT Veh HF.

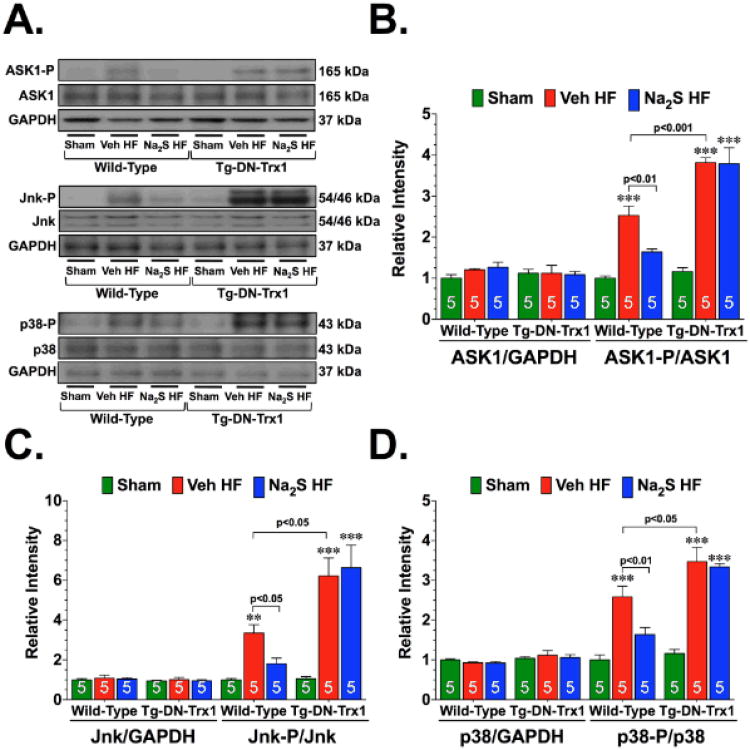

Na2S Therapy Decreased the Heart Failure-Induced Activation of the ASK1-JNK/p38 Signaling Cascade in a Trx1-dependent Manner

Experiments were then conducted to investigate potential mechanisms by which Trx1 mediates the protective effects of Na2S therapy. In the heart, Trx1 plays a pro-survival role in response to stress by inhibiting ASK115 and modulating the nuclear localization of class II histone deacetylases (HDACs).16 Therefore, subsequent experiments focused on these two downstream targets of Trx1.

ASK1 regulates cardiac remodeling in response to different heart failure stimuli via the activation of p38 MAPK and JNK.3,17,18 Experiments were therefore conducted to examine whether the activation of ASK1 signaling accompanied the development of ischemic-induced heart failure and whether Na2S therapy could alter any changes. Analysis of heart homogenates from WT mice revealed that 1-week after the induction of heart failure there was a significant increase (Figure 5A-B; p<0.001 vs. WT Sham) in the phosphorylation of ASK1 at threonine residue 845 (ASK1-P; phosphorylation here is indicative of activation). This was accompanied by a significant increase in the phosphorylation of Jnk (Jnk-P; threonine residue 183 and tyrosine residue 185), and p38 (p38-P; threonine residue 180 and tyrosine residue 182) (Figure 5A and 5C-D; p<0.001 and p<0.01 vs. WT Sham, respectively), suggesting that ASK1 signaling was activated in response to heart failure. However, treatment with Na2S attenuated the heart failure induction of ASK1 signaling, as evidenced by a significant decrease in the phosphorylation of ASK1, Jnk, and p38 (p<0.05 vs. WT Veh HF). No differences in total protein were observed in ASK1, Jnk, or p38.

Figure 5.

Na2S therapy attenuates the heart failure-induced activation of the ASK1-JNK/p38 signaling cascade in a Trx1-dependent manner. (A) Representative immunoblots and densitometric analysis of (B) total and phosphorylated Apoptosis Signaling Kinase 1 (ASK1) at threonine residue 845 (ASK1-P), (C) total and phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) at threonine residue 183 and tyrosine residue 185 (JNK-P), and (D) total and phosphorylated p38 at threonine residue 180 and tyrosine residue 182 (p38-P) from the hearts of WT Sham, WT Veh HF, WT Na2S HF, Tg-DN-Trx1 Sham, Tg-DN-Trx1 Veh HF, and Tg-DN-Trx1 Na2S HF mice collected 1 week after the induction of heart failure. Values are means ±SEM. **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 vs. Sham.

Next, experiments evaluated if Trx1 mediated the attenuation of the ASK1-JNK/p38 signaling cascade in response to Na2S therapy. For these experiments, Tg-DN-Trx1 mice were subjected to heart failure and Na2S treatment as before. Heart failure signaling increased the ASK1-Jnk/p38 signaling cascade in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice, as evidenced by an increased phosphorylation of ASK1, JNK, and p38 (Figure 5A-D, p<0.05, p<0.001, and p<0.05 vs. Tg-DN-Trx1 Sham, respectively). In all cases, the increase in the phosphorylation of ASK1, JNK, and p38 in the Tg-DN-Trx1 hearts was higher than the increase observed in the WT heart (p<0.05 or p<0.001 vs. WT Veh HF). Na2S therapy failed to decrease the heart failure-induced phosphorylation of ASK1, Jnk, or p38 in the Tg-DN-Trx1 mice. Again, no differences in total protein were observed in ASK1, Jnk, or p38. This data suggests that Na2S therapy requires Trx1 to inhibit the ASK1-Jnk/p38 signaling cascade initiated by heart failure.

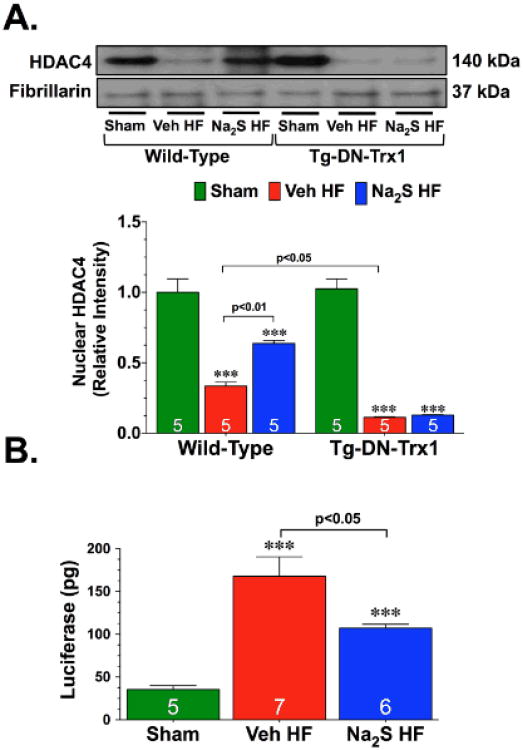

Na2S Therapy Attenuated the Heart Failure-Induced Nuclear Export of HDAC4 in a Trx1-dependent manner

HDACs regulate a number of biological processes, largely through their repressive influence on transcription.19 In particular, HDAC influences the activity of nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), a pro-cardiac hypertrophy transcription factor.20 Trx1 protects the heart from stress by modulating the nuclear export of HDAC4.16 Therefore, experiments were performed to determine if the attenuation in cardiac hypertrophy observed following Na2S therapy was associated with changes in HDAC4 nuclear expression and NFAT activity. Analysis revealed that 1-week after the induction of heart failure there was a significant decrease in the nuclear expression of HDAC4 (Figure 6A; p<0.001 vs. WT Sham). Importantly, Na2S therapy attenuated this heart failure-induced export of HDAC4 (p<0.05 vs. WT Veh HF). Further studies were then conducted to determine if the changes in nuclear HDAC4 levels resulted in the activation of NFAT. For these studies, NFAT-Luciferase reporter mice were subjected to heart failure and Na2S therapy. Heart failure induced a significant increase in the activity of NFAT, as evidenced by an increase in the luciferase activity measured in the hearts of Veh HF and Na2S HF mice (Figure 6B; p<0.001 vs. WT Sham). However, the Na2S HF mice displayed significantly lower luciferase activity when compared to the Veh HF mice (p<0.05). This data suggests that the reduction in cardiac hypertrophy observed in the Na2S HF mice could possibly be mediated through the actions of HDAC4 on NFAT transcriptional activity.

Figure 6.

Na2S therapy prevents the heart failure-induced nuclear export of HDAC4 in a Trx1-dependent manner. (A) Representative immunoblots and densitometric analysis of nuclear histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) from the hearts of WT Sham, WT Veh HF, WT Na2S HF, Tg-DN-Trx1 Sham, Tg-DN-Trx1 Veh HF, and Tg-DN-Trx1 Na2S HF mice collected 1 week after the induction of heart failure. (B) Cardiac luciferase activity from the hearts of NFAT-Luciferase reporter mice subjected to heart failure and Na2S treatment. Values are means ±SEM. ***p<0.001 vs. Sham.

To determine if Trx1 was needed for Na2S therapy to prevent the heart failure-induced nuclear export of HDAC4, Tg-DN-Trx1 mice were subjected to heart failure and Na2S treatment as before. These experiments found that heart failure increased the nuclear export of HDAC4 and that Na2S therapy failed to decrease this export (Figure 6A), suggesting that Na2S therapy requires Trx1 to prevent the nuclear export of HDAC4 after the imitation of heart failure.

Discussion

The cytoprotective effects of H2S have been documented in numerous models of injury, including heart failure. For instance, Mischra et al21 reported that treatment with H2S in the drinking water of mice attenuated the adverse remodeling of the LV in an arteriovenous fistula model of chronic heart failure. Additionally, Givvimani et al22 found that treatment with H2S in the drinking water mitigated the transition from compensatory hypertrophy to heart failure in response to aortic banding. Finally, it was reported that both endogenous and exogenous H2S improved survival and attenuated the morphological and functional impairments of the LV in mice following the initiation of ischemic-induced heart failure.5 The present study further supports these previous findings and provides evidence that treatment with Na2S during the first 7 days of reperfusion not only improves LV dilatation and function during the development of ischemic-induced heart failure, but also improves LV contractility and relaxation, as well as attenuates the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Together, these findings suggest that treatment with H2S attenuates adverse LV remodeling in response to different heart failure stimuli.

H2S has the ability to attenuate many of the processes that lead to LV remodeling.23 In terms of cellular targets, Na2S therapy increases the transcriptional activity of Nuclear-factor-E2-related factor-2, increases the phosphorylation of Akt5, suppresss matrix metalloproteinases21, and increases vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis.22 The activation/inhibition of these proteins certainly contributes to the protective effects observed in the current study. However, given the nature of H2S as a gasotransmitter to activate multiple signaling pathways at the same time4, it can be hypothesized that other cellular targets are involved. Therefore, the main goal of the current study was to evaluate the role that Trx1 plays in mediating the cardioprotective effects of Na2S therapy. Trx1, a small redox-active multifunctional protein, acts as a potent antioxidant and a redox-regulator24 of many cellular processes.25,26 Trx1 plays a pro-survival role in response to myocardial injury by reducing cardiac hypertrophy and apoptosis.11,13,14 Therefore, it was postulated that Trx1 could potentially mediate the protective effects of Na2S therapy in the setting of ischemic-induced heart failure because of these reported cardioprotective effect and because it was previously found that the protein expression of Trx1 was upregulated by a single injection of Na2S.4 However, it was not known if multiple injections of Na2S could maintain the elevated levels of Trx1. As such, the current study is the first to provide evidence that 7 days of Na2S therapy not only increases the gene and protein expression of Trx1 in the absence of ischemia, but that it augments the heart failure-induced increase in both, as well as increases Trx1 activity. More importantly, the current study provides direct evidence to support the hypothesis that Trx1 mediates the cardioprotective effects of Na2S therapy, as evidenced by the findings that Na2S therapy failed to improve cardiac dilatation, dysfunction, or hypertrophy in Tg-DN-Trx1 mice.

Another major finding of the current study relates to the mechanism that Na2S therapy signals through Trx1 to attenuate the adverse remodeling of LV during heart failure. Specifically, the current study provides important insights into the effects of Na2S therapy on ASK1-mediated signaling and HDAC nuclear expression. ASK1 is strongly activated in various cell types in response to stimuli such as oxidative stress and TNF alpha.27 In the heart, ASK1 has emerged as a kinase of essential importance given its prevailing role in regulating cell death and cardiac remodeling via the activation of p38 MAPK and Jnk.3,17,18 Numerous proteins interact with ASK1 through protein-protein interactions to regulate its activity. In particular, Trx1 was identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen as a negative regulator of the ASK1-Jnk/p38 pathway.28 Under normal conditions, ASK1 constantly forms an inactive complex with Trx1. However, in response to the oxidative stress following myocardial infarction, Trx1 releases ASK1 enabling it to phosphorylate Jnk and p3815, which ultimately leads to pathological LV structural and functional remodeling.3 The findings of the current study support the hypothesis that activation of ASK1 contributes to the development of heart failure following myocardial infarction, as evidenced by the finding that the improvements in LV dilatation and function in response to Na2S therapy are associated with a suppression of the ASK1-Jnk/p38 pathway. More importantly, the current study provides evidence for the first time that Na2S therapy inhibits ASK1-Jnk/p38 signaling in a Trx1-dependent manner, as evidenced by the findings that Na2S therapy fails to reduce the phosphorylation of ASK1, Jnk, or p38 in Tg-DN-Trx1 mice.

The control of histone deacetylation by HDACs has been reported to be central point for the control of cardiac growth and gene expression in response to acute and chronic stress stimuli.20 In response to stress stimuli, the expression of class II HDACs do not change. Rather, HDACs are shuttled from the nucleus to the cytosol, where then can no longer suppress target transcription factors.20 In the heart, pathophysiological stress signals associated with heart failure stimulate the nuclear export of HDAC4.29 This in turn elicits the activation of NFAT, which ultimately leads to the development of cardiac hypertrophy.20 Trx1 modulates the development of cardiac hypertrophy by regulating the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of HDAC4.16 Based on this evidence and the findings that Na2S therapy attenuated cardiac hypertrophy in a Trx1-dependent manner, the current study also sought to determine if Na2S therapy could alter the nuclear expression of HDAC4 in response to ischemic-induced heart failure. For the first time, the results of the current study provide evidence that Na2S therapy attenuated the heart failure-induced nuclear export of HDAC4 in a Trx1-dependent manner and attenuated the heart failure-induced activation of NFAT. Together these findings suggest that an additional mechanism of action for Na2S therapy in the setting of ischemic-induced heart failure involves the prevention of the nuclear export of HDAC4 resulting in the inhibition of NFAT.

Although the current study demonstrates a dependence on Trx1 for Na2S therapy to provide cardioprotection in the setting of heart failure, there are a few caveats that need to be noted. First, in the original description of the Tg-DN-Trx1 mouse11, it was reported that elevations in oxidative stress induced cardiac hypertrophy with maintained cardiac function under baseline conditions. Although this was not observed in the current study, care should be taken when considering the effects of Trx1 inactivity and Na2S treatment on the development of cardiac hypertrophy following ischemic-induced heart failure. Second, these experiments cannot completely rule out the contribution of Trx1-independent mechanisms. For example, Akt, which is activated by Na2S5, has been shown to inhibit ASK130 and could possibly contribute to the suppression of ASK1 signaling. Additionally, the activation of protein kinase C, which is also induced by Na2S4, can regulate the phosphorylation of Jnk and p38 in an ASK1-independent manner31.

In summary, this study provides novel evidence that Na2S therapy attenuates LV dilatation, LV dysfunction, and LV hypertrophy in the setting of ischemic-induced heart failure in a Trx1-dependent manner. Furthermore, these findings provide important information that the upregulation of cardiac Trx1 by Na2S in the setting of heart failure sets into motion events, such as the inhibition of ASK1 signaling and HDAC4 nuclear export, which ultimately leads to an attenuation of LV remodeling. Since, patients with major remodeling demonstrate progressive worsening of cardiac function, preventing, slowing or reversing remodeling is a goal of any heart failure therapy.3 Therefore, the findings of the current study continue to support the emerging concept that treatment strategies aimed at increasing the levels of H2S may be of clinical importance in reducing the mortality and morbidity associated with heart failure.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Therapeutic strategies aimed at increasing the levels of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) have been shown to exert cytoprotective effects in various models of heart failure. The current study expanded on these initial findings and sought to investigate the role that thioredoxin-1 (Trx1) plays in mediating these effects. Specifically, this study provides novel evidence that treatment with H2S in the form of sodium sulfide (Na2S) attenuates LV dysfunction and hypertrophy in the setting of ischemic-induced heart failure in a Trx1-dependent manner. Furthermore, these findings provide important information that the upregulation of cardiac Trx1 by Na2S sets into motion events, such as the inhibition of apoptosis signaling kinase-1 (ASK1) signaling and histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) nuclear export, which ultimately leads to an attenuation of LV remodeling. Together, these findings further support the emerging concept that H2S therapy may be of clinical importance in the treatment of heart failure.

Acknowledgments

None

Sources of funding: Supported by grants from the American Diabetes Association (7-09-BS-26) and the National Institutes of Health National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (5R01HL098481-03) to J.W.C. This work was also supported by funding from the Carlyle Fraser Heart Center (CFHC) of Emory University Hospital Midtown.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Koitabashi N, Kass DA. Reverse remodeling in heart failure--mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:147–157. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon SD, Pfeffer MA. The decreasing incidence of left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 1997;92:61–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00805561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguchi O, Higuchi Y, Hirotani S, et al. Targeted deletion of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 attenuates left ventricular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15883–15888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136717100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvert JW, Jha S, Gundewar S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Pattillo CB, Kevil CG, Lefer DJ. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through nrf2 signaling. Circ Res. 2009;105:365–374. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.199919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvert JW, Elston M, Nicholson CK, Gundewar S, Jha S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, Lefer DJ. Genetic and pharmacologic hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates ischemia-induced heart failure in mice. Circulation. 2010;122:11–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.920991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salloum FN, Chau VQ, Hoke NN, Abbate A, Varma A, Ockaili RA, Toldo S, Kukreja RC. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, tadalafil, protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion through protein-kinase g-dependent generation of hydrogen sulfide. Circulation. 2009;120:S31–36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.843979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvert JW, Coetzee WA, Lefer DJ. Novel insights into hydrogen sulfide--mediated cytoprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1203–1217. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordberg J, Arner ES. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidants, and the mammalian thioredoxin system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1287–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ago T, Sadoshima J. Thioredoxin and ventricular remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:762–773. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kishimoto C, Shioji K, Nakamura H, Nakayama Y, Yodoi J, Sasayama S. Serum thioredoxin (trx) levels in patients with heart failure. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:491–494. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto M, Yang G, Hong C, Liu J, Holle E, Yu X, Wagner T, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Inhibition of endogenous thioredoxin in the heart increases oxidative stress and cardiac hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1395–1406. doi: 10.1172/JCI17700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Ago T, Zhai P, Abdellatif M, Sadoshima J. Thioredoxin 1 negatively regulates angiotensin ii-induced cardiac hypertrophy through upregulation of mir-98/let-7. Circ Res. 2011;108:305–313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.228437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh M, Matter CM, Ogita H, Takeshita K, Wang CY, Dorn GW, 2nd, Liao JK. Inhibition of apoptosis-regulated signaling kinase-1 and prevention of congestive heart failure by estrogen. Circulation. 2007;115:3197–3204. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.657981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tao L, Gao E, Bryan NS, Qu Y, Liu HR, Hu A, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Yodoi J, Koch WJ, Feelisch M, Ma XL. Cardioprotective effects of thioredoxin in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion: Role of s-nitrosation [corrected] Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11471–11476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402941101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang K, Li X, Zheng MQ, Rozanski GJ. Role of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase-1-c-jun nh2-terminal kinase-p38 signaling in voltage-gated k+ channel remodeling of the failing heart: Regulation by thioredoxin. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:25–35. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ago T, Liu T, Zhai P, Chen W, Li H, Molkentin JD, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. A redox-dependent pathway for regulating class ii hdacs and cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 2008;133:978–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. Induction of apoptosis by ask1, a mammalian mapkkk that activates sapk/jnk and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Sargent MA, York AJ, Molkentin JD. Ask1 regulates cardiomyocyte death but not hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2009;105:1110–1117. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.200741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: Implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Backs J, Olson EN. Control of cardiac growth by histone acetylation/deacetylation. Circ Res. 2006;98:15–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000197782.21444.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra PK, Tyagi N, Sen U, Givvimani S, Tyagi SC. H2s ameliorates oxidative and proteolytic stresses and protects the heart against adverse remodeling in chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H451–456. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00682.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Givvimani S, Munjal C, Gargoum R, Sen U, Tyagi N, Vacek JC, Tyagi SC. Hydrogen sulfide mitigates transition from compensatory hypertrophy to heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2011;110:1093–1100. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01064.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson CK, Calvert JW. Hydrogen sulfide and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaimul AM, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Yodoi J. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin-binding protein-2 in cancer and metabolic syndrome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo N, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Yodoi J. Redox regulation of human thioredoxin network. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1881–1890. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Min W. Thioredoxin promotes ask1 ubiquitination and degradation to inhibit ask1-mediated apoptosis in a redox activity-independent manner. Circ Res. 2002;90:1259–1266. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000022160.64355.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishida K, Otsu K. The role of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1729–1736. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, Takeda K, Tobiume K, Sawada Y, Kawabata M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H. Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ask) 1. EMBO J. 1998;17:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calalb MB, McKinsey TA, Newkirk S, Huynh K, Sucharov CC, Bristow MR. Increased phosphorylation-dependent nuclear export of class ii histone deacetylases in failing human heart. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2009.00141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim AH, Khursigara G, Sun X, Franke TF, Chao MV. Akt phosphorylates and negatively regulates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:893–901. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.893-901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dana A, Skarli M, Papakrivopoulou J, Yellon DM. Adenosine a(1) receptor induced delayed preconditioning in rabbits: Induction of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and hsp27 phosphorylation via a tyrosine kinase- and protein kinase c-dependent mechanism. Circ Res. 2000;86:989–997. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.