Abstract

This descriptive, cross-sectional, secondary data analysis was conducted to examine racial disparities in pain management of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain using chronic opioid therapy. Data from 891 patients, including 201 African Americans and 691 Caucasians were used to test an explanatory model for these disparities. We predicted that: (1) African American patients would report worse pain management and poor quality of life (QOL) than Caucasians; (2) the association between race and pain management would be mediated by perceived discrimination relating to hopelessness; and (3) poor pain management would negatively affect QOL. Results revealed significant differences between African Americans and Caucasians on pain management and QOL, with African Americans faring worse. The proposed mediational model, which included race, perceived discrimination, hopelessness, and pain management was supported: (1) African Americans compared to Caucasians had higher perceived discrimination, (2) perceived discrimination was positively associated with hopelessness, and (3) higher hopelessness was associated with worse pain management. Further, pain management predicted QOL. This is the first study in which an explanatory model for the racial disparities in pain management of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain was examined. Perceived discrimination and hopelessness were implicated as explanatory factors for the disparities.

Keywords: Pain Management, Chronic nonmalignant pain, Model of racial disparities, racial and ethnic minorities, perceived discrimination

INTRODUCTION

There are racial disparities in pain management in the United States. Systematic literature reviews revealed that African Americans are more at risk than Caucasians for experiencing under-treatment of pain (Cintron & Morrison, 2006; Ezenwa, Ameringer, Ward, & Serlin, 2006; Meghani, Byun, & Gallagher, 2012). There are several important gaps in our understanding of disparities in pain management, including a lack of attention to disparities in pain management in primary care settings. Investigators of only one study examined racial disparities in the pain management of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain (Chen et al., 2005). Chen and colleagues found that African Americans reported worse pain scores than Caucasians (Chen, et al., 2005). No study, however, provides insights about explanatory models that would further our understanding of disparities. The purpose of this study was to examine whether there are racial disparities in pain management of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain using chronic opioid therapy and to test an empirical model that proposes an explanation for these disparities.

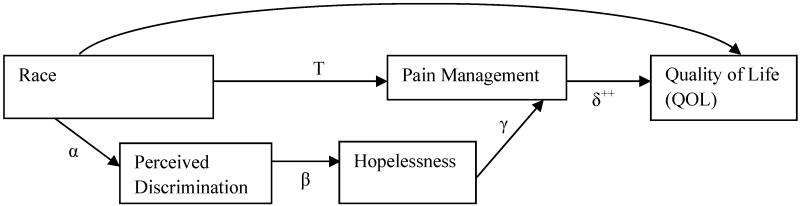

The proposed explanatory model, which addresses relationships among perceived discrimination, hopelessness, and racial disparities in proximal [pain management] and distal [quality of life] pain outcomes, is based on a synthesis of research on pain treatment, perceived discrimination, and hopelessness and their impact on health outcomes. We define everyday perceived discrimination as chronic, routine, and relatively minor experiences of unfair treatment (Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Hopelessness is defined as a negative expectation about one’s present and future life (Everson, Kaplan, Goldberg, Salonen, & Salonen, 1997). These concepts have been examined in other healthcare areas. For example, African Americans who reported perceived discrimination are more likely to have higher diastolic blood pressure than their Caucasian counterparts (Lewis et al., 2009). Further, African Americans who reported feelings of hopelessness are more at risk for mortality than their Caucasian counterparts (Fiscella & Franks, 1997). Investigators have not examined the effects of perceived discrimination and hopelessness on pain management disparities, especially not in primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain who were using chronic opioid therapy.

However, the available research evidence supports several assertions. Investigators have found that the experience of racial discrimination is more common among African Americans than Caucasians (Feagin & Feagin, 1991; Krieger, 1990). For example, 43% of African Americans compared to 4% of Caucasians report experiencing discrimination regularly (Ren, Amick, & Williams, 1999). Others have reported that hopelessness adversely affects health and that there are differential racial effects in which African Americans suffer the most compared to Caucasians (Anda et al., 1993; Fiscella & Franks, 1997). For instance, 40% of African Americans report having a hopeless outlook compared to 28% of Caucasians (Fiscella & Franks, 1997). The experience of perceived discrimination may evoke fear, self-doubt, and anger (Krieger, 1990). Others have reported that patients who blamed discrimination for their failures also reported greater hopelessness (Rusch et al., 2009). In this study, we focused on the effect of everyday perceived discrimination on hopelessness. Perceived discrimination, which is related to feelings of hopelessness, could, at least in part, explain racial disparities in pain management. Finally, investigators have suggested that quality of life (QOL) issues are huge concerns in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Patients with chronic nonmalignant pain usually report lower quality of life compared to the general population (Dillie, Fleming, Mundt, & French, 2008; Fredheim et al., 2008; Tuzun, 2007).

Using these research findings to better understand the relationship among these variables in primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain, we proposed that: (1) African American patients will report worse pain management and poorer QOL than Caucasians; (2) the association between race and pain management will be mediated by perceived discrimination relating to hopelessness; and (3) poor pain management will negatively affect QOL. Unfortunately, previous investigators have not explored the influence of perceived discrimination on hopelessness and pain management in primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain who were using chronic opioid therapy. The specific study aims were to: (1) examine the relationship between race and proximal (pain management) and distal (QOL) pain outcomes, (2) test whether perceived discrimination relating to hopelessness mediates the relationship between race and pain management, and (3) test whether pain management influences QOL (See Figure).

Figure.

Conceptual Model of Racial Disparities in Pain Management.

Note. α = race - perceived discrimination path; β = perceived discrimination – mediator (Hopelessness) path; γ = mediator – pain management path; and δ = pain management – quality of life path; ++ A separate aim. Not part of the mediator factor.

METHODS

Design

This study was a descriptive, cross-sectional, secondary analysis of an existing dataset. Data were collected from primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain in a single state in the Midwestern United States.

Parent study

Human Subjects Committees in each of six participating healthcare systems approved the parent study. Eligibility criteria were: being 18 years or older, having chronic nonmalignant pain that had lasted for at least three months, and being treated with opioid therapy. Note that the perceived discrimination questionnaire was added after the study began. The first group of recruited participants (N = 93) did not complete this questionnaire. More details about the methods of the parent study are reported elsewhere (Fleming, Balousek, Klessig, Mundt, & Brown, 2007).

Subjects and Procedures

Of the 1009 participants in the original dataset, 914 (90.6%) completed the perceived discrimination questionnaire. We had a total of 892 participants when the inclusion criteria of being African American or Caucasian and having completed the perceived discrimination questionnaire were applied to the dataset. The mean (SD) age of participants was 49.07 (10.54) years; ranged from 18-81 years. The majority were Caucasian (n = 691, 77.5%) and female (n = 624, 70.0%). Other patients’ sociodemographic characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Variables of all Participants and broken down by African Americans versus Caucasians (N=892).

| Variable | All participants | African American |

Caucasian | Test Statistics and P-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| N= 892 | N= 201 | n= 691 | ||

| Age-Mean (SD) | 49.07 (10.54) | 49.42 (9.61) | 48.97 (10.81) |

U =67399.00, p =.52 |

| Min-Max | 18-81 | 19-71 | 18-81 | |

| Gender- n (%) | X2 = .01, p = .95 | |||

| Male | 268 (30.00) | 60 (29.90) | 208 (30.10) | |

| Female | 624 (70.00) | 141 (70.10) | 483 (69.90) | |

| Education (yrs)- Mean (SD) |

13.15 (2.51) | 11.88 (2.12) | 13.51 (2.49) |

U =42845.00, p < .001 |

| Min-Max | 1-24 | 1-18 | 4-24 | |

| Monthly income ($) -Mean (SD) |

772 (1,684) | 220 (752) | 932 (1,840) |

U =48388.00, p <.001 |

| Min-Max | 0-24,400 | 0-7,300 | 0-24,400 | |

| Employment- n (%) |

X2 = 56.69, p<.001 | |||

| Full time | 279 (31.30) | 29 (14.40) | 250 (36.20) | |

| Part time | 75 (8.40) | 9 (4.50) | 66 (9.60) | |

| Part time (irreg., daywork) |

37 (4.10) | 7 (3.50) | 30 (4.30) | |

| Student | 11 (1.20) | 1 (0.50) | 10 (1.40) | |

| Retired/disability | 402 (45.10) | 134 (66.70) | 268 (38.80) | |

| Unemployed | 88 (9.90) | 21 (10.40) | 67 (9.70) | |

| Religion- n (%) | X2 = 53.04, p<.001 | |||

| Protestant | 430 (48.20) | 129 (64.20) | 301 (43.60) | |

| Catholic | 171 (19.20) | 18 (9.00) | 153 (22.10) | |

| Jewish | 5 (0.60) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (0.70) | |

| Islamic | 2 (0.20) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.30) | |

| Other | 69 (7.70) | 27 (13.40) | 42 (6.10) | |

| None | 215 (24.10) | 27 (13.40) | 188 (27.20) | |

| Disability- n (%) | X2 = 56.46, p<.001 | |||

| No | 491 (55.00) | 64 (31.80) | 427 (61.80) | |

| Yes | 401 (45.00) | 137 (68.20) | 264 (38.20) | |

| Comorbidity- n (%) |

Not obtained | |||

| No | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Yes | 892 (100.00) | 201 (100.0) | 691 (100.00) | |

| Years since pain diagnosis- Mean |

18.03 (12.71) | 18.21 (12.85) | 17.98 (12.68) |

U =68488.00, p=.79 |

| (SD) | ||||

| Years since first clinic visit- M(SD) |

16.61 (11.80) | 17.08 (12.13) | 16.48 (11.71) |

U =67037.00, p=.52 |

| Years since first opioid use- Mean (SD) |

13.92 (71.34) | 12.71 (10.51) | 14.28 (81.21) | U =51475.00, p=.14 |

MEASURES

We used two outcome measures as shown in Table 2. The Pain Management Composite Score was created in two steps using pain severity (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994; Tan, Jensen, Thornby, & Shanti, 2004), opioid dose used, and satisfaction with pain treatment (Ho & LaFleur, 2004) according to the procedure described by Marascuilo and Levin (Marascuilo & Levin, 1983). Scholars recommend that when the main outcome scores are equally important, as is the case with these three concepts that make up the pain management construct, they should be replaced with a single outcome summary score, such as pain management composite score (Schouten, 2000). Using this approach, we preserve degrees of freedom, conserve sample size, and improve the power of statistical tests (Schouten, 2000). Further, these measures have demonstrated adequate reliability alphas in previous studies (Cleeland & Ryan, 1994; Tan, et al., 2004). In the current study, the reliability alpha of pain severity scale was .76, and for the satisfaction scale the alpha was .86. Opioid dose used was computed by converting all opioid medications to morphine equivalents per day and this was the value used in data analyses. For example, a larger opioid dose used for moderate to severe pain intensity indicated better pain management.

To create the pain management composite score, first, Z-scores of pain severity, opioid dose used, and satisfaction with pain treatment were created in order to standardize them to the same scale with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. Second, the Z-scores of opioid dose used and satisfaction with pain treatment were added together, and the Z-score of pain severity was then subtracted. The Z-scores for opioid dose used and satisfaction with pain treatment were added because higher scores on these variables are desirable. The Z-score for pain severity was subtracted because higher score on this variable is not desirable. A higher pain management composite score reflects better pain management. The pain management composite score demonstrated its validity in this sample. The score correlated in the predicted direction with quality of life [SHARP X2(1, N = 888) = 54.96, p < .001], showing the validity of the score.

Quality of life was measured using the RAND-36 Health Survey 1.0 (a modified SF-36 Health Survey), a multi-item measure of health-related QOL in eight domains (Goertz, 1994). Scores ranged from 0 (low) to 100 (high), with lower scores indicating poor QOL. Items were averaged to form 8 subscales. The internal consistency of the eight subscales in a previous study ranged from .73 to .96 (Brazier et al., 1992) and in this sample ranged from .72 to .91. A QOL composite score was created by converting scores to Z-scores. The reliability alpha for the QOL composite score in this sample was .85.

Two mediating measures were used: Everyday perceived discrimination and hopelessness. Perceived discrimination was measured with 9 items (Williams, et al., 1997). Response options ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). An overall perceived discrimination score was computed by taking the mean of these items. Higher scores indicated greater perceived discrimination. This scale has a good reliability (α) of .88 (Williams, et al., 1997) and has been validated in both younger and older populations (Barnes et al., 2004; Finch, Kolody, & Vega, 2000; Williams, et al., 1997) and in this sample the reliability alpha was .89. Hopelessness was measured with two items, which were part of the Pain Patient Profile (P-3) that measured emotional functioning in patients with pain (Willoughby, Hailey, & Wheeler, 1999). Each item is followed by three general statements about expectations about one’s present and future life, indicating: (1) low, (2) moderate, and (3) high hopelessness. A total hopelessness score was calculated by taking the mean of these two items. Higher scores indicated higher hopelessness. The reliability alpha in this sample was .73.

ANALYSIS

SPSS for Windows Version 16.0 (2007; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses. Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the demographic and clinical variables of the sample. Mann-Whitney U-tests were used to compare African Americans and Caucasians on ordered variables, whereas the Fisher exact test and exact p-values were used to compare African Americans and Caucasians on unordered categorical variables. The Serlin-Harwell Aligned-Ranked Procedure (SHARP), a non-parametric regression analysis technique appropriate for non-normally distributed data (Serlin & Harwell, 2004), was used to test for differences between the medians of African Americans and Caucasians on pain outcomes: pain management composite score and QOL composite score (Serlin & Harwell, 2004). Each analysis was allotted a Type I error rate of 0.05.

Further, a series of multiple regression analyses were used to test for mediation based on the joint significance test approach (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). The joint significance approach to mediation is the best of the all the causal steps approaches because it has more statistical power and the lowest Type I error rate (Krause et al., 2010). Table 3 lists the variables tested in the model. Evidence of mediation effects was deduced when tests of the race – perceived discrimination path (α), perceived discrimination – hopelessness path (β), and hopelessness – pain management path (γ) were all significant. To test the α path, age, income, education, and disability were used as covariates, race and gender, were used as the independent variables, and perceived discrimination was the dependent variable. In testing the β path, the pooled within-group relationship between perceived discrimination and hopelessness was evaluated, controlling for covariates, with race and gender as independent variables. To test the γ path, the pooled within-group relationship between hopelessness and pain management was examined, controlling for perceived discrimination and covariates, with race, gender as independent variables. Further, the pain management – QOL path (δ) was examined. In testing the δ path, the pooled within-group relationship between pain management and QOL was examined using the pain management composite score as the independent variable and QOL composite score as the dependent variable, controlling for perceived discrimination, hopelessness, race, gender, and covariates– age, income, education, and disability. Paths were tested using the SHARP procedure. Each analysis was assigned a Type I error rate of 0.05.

Table 3. Variables Included in Testing the Model of Racial Disparities in Pain Management.

| Paths | Covariates | Independent variable(s) |

Dependent variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race-perceived discrimination (α) |

Age Income Education Disability |

Race** Gender |

Perceived discrimination |

| Perceived discrimination– mediator (Hopelessness) path (β) |

Age Income Education Disability |

Race Gender Perceived discrimination** |

Hopelessness |

| Mediator – pain management path (γ) |

Age Income Education Disability |

Race Gender Perceived discrimination Hopelessness** |

Pain management |

| Pain management – quality of life path (δ) |

Age Income Education Disability |

Race Gender Perceived discrimination Hopelessness Pain Management** |

Quality of life |

Note. Independent variable(s) being tested in each path.

RESULTS

Comparison of African Americans and Caucasians on Demographic and Clinical Variables

African Americans and Caucasians were compared on demographic and clinical variables (Table 1). We found that African Americans earned less income than Caucasians Mann-Whitney U = 48388.00, n1 = 691, n2 = 201, p < .001, α = .35 (α is a measure of stochastic superiority that indicates the probability that an observation from one population will exceed an observation from another population; here, α = .35 indicates that the probability is .65 that an African American will have lower income than a Caucasian), and had fewer years of education than Caucasians, Mann-Whitney U = 42845.00, n1 = 691, n2 = 201, p < .001, α = .31 (probability is .69 that an African Americans will have fewer years of education). There was a statistically significant difference between African Americans and Caucasians regarding employment X2(1, N = 892) = 56.69, p < .001, φ = .25. Greater proportions of Caucasians were working a full-time job (36.2%) or part-time job (9.6%) than the proportions of African Americans working a full-time job (14.4%) or part-time job (4.5%). Greater proportions of African Americans were retired/disabled (66.7%) or unemployed (10.4%) than the proportions of Caucasians who were retired/disabled (38.8%) or unemployed (9.7%). There were no significant differences between African Americans and Caucasian on median age and gender.

Further, African Americans were significantly more likely to report chronic pain-related disability than Caucasians [X2(1, N = 892) = 56.46, p < .001, φ = .25]. There were no significant differences between African Americans and Caucasians on years since pain diagnosis, years since first visit to pain clinic, and years since first opioid use.

Relationship between Race and Pain Outcomes

There was a statistically significant difference between the medians of African Americans and Caucasians on pain management composite scores SHARP [X2(1, N = 890) = 38.94, p < .001, Squared Partial Correlation Coefficient = .04] controlling for age, gender, income, education, and disability. The direction of the slope indicates that African Americans reported worse pain management scores than Caucasians. Further, race was a significant predictor of QOL SHARP [X2(1, N = 889) = 10.76, p < .001, Squared Partial Correlation Coefficient = .02] controlling for age, income, education, disability, and gender. The race slope indicated that African Americans reported lower QOL scores than Caucasians.

Test of Mediation Model

Tables 2 and 3 provide the description of variables included for testing each path in the model. The race–perceived discrimination path (α) was significant, which indicated that race was a significant predictor of perceived discrimination SHARP [X2(1, N = 891) = 5.57, p = .02, Squared Partial Correlation Coefficient = .01]. The slope for race indicated that African Americans reported more perceived discrimination than Caucasians. The perceived discrimination – hopelessness path (β) was significant, demonstrating that perceived discrimination was a significant predictor of hopelessness SHARP [X2(1, N = 890) = 39.87, p < .001, Squared Partial Correlation Coefficient = .05]. The slope for perceived discrimination indicated that higher scores on perceived discrimination were associated with higher hopelessness scores. The hopelessness – pain management path (γ) was significant, which shows that hopelessness was a significant predictor of pain management SHARP [X2(1, N = 890) = 42.11, p < .001, Squared Partial Correlation Coefficient = .05]. The slope for hopelessness indicated that lower hopelessness was related to better pain management.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Mediating and Outcome Variables by Race (N = 892). African Americans (n = 201) and Caucasians (n = 691).

| Variable and Race | Mean (SD) | Median | Mode | Min-Max (Obtained) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived discrimination | ||||

| African Americans | 2.01 (0.81) | 1.89 | 1.00 | 1-5 |

| Caucasians | 1.77 (0.65) | 1.67 | 1.00 | 1-4.78 |

| Hopelessness | ||||

| African Americans | 1.52 (0.63) | 1.50 | 1.00 | 1-3 |

| Caucasians | 1.50 (0.59) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1-3 |

| Pain Management | ||||

| African Americans | −.78 (1.78) | −.94 | −2.43 | −5.34-5.57 |

| Caucasians | .22 (1.74) | .21 | .08 | −4.70-7.15 |

| Quality of Life | ||||

| African Americans | −2.12 (4.88) | −2.30 | −11.74 | −11.74-12.42 |

| Caucasians | .63 (5.66) | .21 | −12.57 | −12.57-16.26 |

Relationship between Proximal and Distal Pain Outcomes

The test of delta path (δ) involved using the pain management composite score as the independent variable and QOL composite score as the dependent variable. This path was significant SHARP [X2(1, N = 888) = 54.96, p < .001, Squared Partial Correlation Coefficient = .06], which indicates that pain management was a significant predictor of QOL. The slope for pain management showed that worse pain management scores were associated with lower QOL.

DISCUSSION

This study provides evidence of racial disparities in pain management of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain who were using chronic opioid therapy in that African Americans reported worse pain management and lower QOL than Caucasians, and provides support for the conceptual model of racial disparities in pain management. The data support the link between race and perceived discrimination. African Americans reported more perceived discrimination than Caucasians. This is the first study to report a relationship between perceived discrimination and hopelessness in primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Higher perceived discrimination was associated with higher hopelessness. This study is also the first to report a relationship between hopelessness and pain management. Lower hopelessness was related to better pain management. Finally, as shown in previous studies in other populations, the findings support the relationship between pain management and QOL in that worse pain management was associated with lower QOL.

One of the major findings of this study is that there are racial disparities in pain management of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. African Americans reported significantly worse pain management scores than Caucasians. These relationships were significant in analyses that controlled for age, income, education, and disability. This finding supports the only previous study of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain, wherein Chen and colleagues found that African Americans with chronic nonmalignant pain also reported worse pain management than Caucasians (Chen, et al., 2005). Similar findings have been reported by other investigators in other pain patient populations including cancer (Bernabei et al., 1998; Cleeland, Gonin, Baez, Loehrer, & Pandya, 1997; Cleeland et al., 1994) and postoperative patients (Karpman, Del Mar, & Bay, 1997; Todd, Deaton, D’Adamo, & Goe, 2000; Todd, Samaroo, & Hoffman, 1993). Several patient-related factors have been suggested such as attitudinal barriers (Ng, Dimsdale, Rollnik, & Shapiro, 1996; Ward & Hernandez, 1994) language barriers, (McDonald, 1994; Todd, et al., 1993) and finances (Rust et al., 2004; Tamayo-Sarver et al., 2003) as explanations for racial disparities for pain management in the United States. Despite the important contributions from these studies, at least three gaps remain: (1) as a body of literature, the results of these studies is inconsistent and limits our conclusions about the findings; (2) none of these factors have been empirically and systematically tested; and (3) majority of these studies did not examine possible psychological factors that explain the disparities in pain management.

The second major finding of this study is that our data supported an empirically and systematically tested model that implicated perceived discrimination and hopelessness as explanatory factors for the racial disparities found in this sample. Regarding perceived discrimination, healthcare researchers have established that perceived discrimination has adverse effects on health outcomes (Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999; Schulz et al., 2006). They have also found racial disparities in the negative impact of perceived discrimination (Lee, Ayers, & Kronenfeld, 2009; Lewis, et al., 2009). For example, African Americans who reported perceived discrimination also had higher diastolic blood pressure than their Caucasian counterparts (Lewis, et al., 2009). The mechanism of action of perceived discrimination on the racial disparities in pain management as proposed in this study was through its relationship to hopelessness. Investigators have found that hopelessness has negative effects on health outcomes and that African Americans are more likely to experience the adverse health consequences of hopelessness than Caucasians (Anda, et al., 1993; Everson et al., 1996; Fiscella & Franks, 1997). Given findings from this body of literature, primary care providers caring for these patients need to be aware that African Americans reporting everyday perceived discrimination may also have a hopeless outlook in life, which may negatively affect their pain management. Assessing and addressing perceived discrimination and feelings of hopelessness during clinical encounters may be important firsts step to help ameliorate the adverse effects of both factors on pain outcomes.

This conceptual model of racial disparities in pain management could be viewed as a “blaming the victim” model. That is, one could view the model as blaming African Americans for perceiving discrimination or having feelings of hopelessness that could possibly lead to poor pain management. We would argue, however, that in this racial disparities model, individuals are not blamed for perceiving discrimination and having feelings of hopelessness. Instead, the blame is placed on the sociopolitical and cultural systems that perpetrated and condoned racism and discrimination, and created an environment that is psychologically toxic to African Americans. African Americans’ world view is, for the most part, through the lenses of racism and discrimination they experienced and over which they had no control. Thus, the society in which this kind of negative experience is possible for only certain members of the population and not others is culpable. For example, one scholar has written that genetics, environmental factors, and the socioeconomic status shape the future of an individual from the moment of birth and that people are “not free to be other than what they are” instead, “they are reflections of their genetics, and the social and economic environment they inhabit”(Dougherty, 1993, p. 114). The contributions of genetics, sociocultural and economic environment as explanatory factors for the racial disparities in pain management in this population will be an invaluable addition to this body of literature.

Since pain management involves patient, provider, and healthcare system interactions, there are patient-related, provider-related, patient-provider-related, and healthcare systems factors that could explain racial disparities in pain management. For example, findings on patient-provider racial concordance and poor patient-provider communication as explanatory factors for racial disparities in pain management will be invaluable in designing patient-provider educational pain management interventions. Examining these factors is outside the scope of the current study, but they need to be examined in future studies.

An alternative model for racial disparities in pain management may be suggested. For example, one may argue that African Americans who experienced worse pain management may also report having feelings of hopelessness compared to Caucasians. That is, poor pain management may precede hopelessness rather than the other way round as suggested by the current model. This alternative model is plausible because hopelessness has been recognized as a psychological response to a physical illness (Dunn, 2005). Thus, it is logical to state that African Americans who report experiencing worse pain management may subsequently report having feelings of hopelessness. Future research could examine other alternative models, and psychological mediators of the relationship between perceived discrimination and pain management disparities such as anger, hostility, and especially depression. A group of investigators found that 66% of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain also reported major depression (Arnow et al., 2006).

Our finding that African Americans reported lower QOL than Caucasians is also important. Similar findings have been reported by others who found racial disparities in QOL in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain (Ibrahim, Burant, Siminoff, Stoller, & Kwoh, 2002). Pain researchers have found that African Americans with chronic nonmalignant pain reported poorer QOL than their Caucasian counterparts (Green, Baker, Smith, & Sato, 2003; Jordan, Lumley, & Leisen, 1998). In cancer patients, it has been reported that African Americans reported poorer QOL than Caucasians (Rao, Debb, Blitz, Choi, & Cella, 2008).

Further, worse pain management was related to lower quality of life. A similar finding has been noted in patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome (Tripp, Curtis Nickel, Landis, Wang, & Knauss, 2004). Taken together, this body of literature suggests that in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain, there are racial disparities in QOL wherein African Americans fair worse. It behooves primary care providers who encounter these patients to routinely assess their QOL and suggest coping strategies for them.

Some limitations of a secondary data analysis detract from this study. Although the relationships proposed in the conceptual model of racial disparities in pain management were supported, one needs to be cautious about claiming that these relationships were causal due to the correlational nature of the study. For example, we could not claim that the experience of perceived discrimination caused the feeling of hopelessness. In addition, because of the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the study, other alternative directions of the relationships among concepts are possible. To overcome this limitation in the future, it is necessary to replicate this study using a prospective longitudinal design. The complete model needs to be tested again in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Another limitation of this study is that patients were recruited from a single state where the ethnic origins of the Caucasians is mostly made up of Germans, Norwegians, and Eastern Europeans who as a group may have a stoic world view. They may respond differently to the perceived discrimination questionnaire than other Caucasians. The same argument is also true of the African American group, which could have included patients from Africa, second generation Africans in the United States, and Caribbeans. An examination of the intra-ethnic differences in response to perceived discrimination would have been invaluable for further interpretation of our findings, but one that is outside the scope of this study, and will be examined in a future study.

Our findings have some policy and research implications. As indicated in the 2011 Institute of Medicine report on Relieving Pain in America, nurses and physicians lack systematic training about the barriers to pain treatment, especially in the primary care settings (Institute of Medicine, 2011) Policymakers, should advocate for increased funding for pain research including research that focus on developing patient-centered pain management interventions for patients and culturally-sensitive educational interventions for providers. Furthermore, patient-provider variables, such as racial concordance, communication skill, and mutual trust should be examined in future studies to ascertain the moderating effect of patient-provider interaction on racial disparities in pain management in primary care settings.

In conclusion, this is the first study to examine an explanatory model for the racial disparities in pain management of primary care patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Perceived discrimination and hopelessness were implicated as explanatory factors for the disparities. Further research is needed to replicate this study using a prospective longitudinal design. These results were obtained after controlling for several demographic and clinical variables that previous research has shown to be confounding variables. Therefore, the findings are interpreted with high confidence.

Acknowledgements

The first author thanks Sandra E. Ward, PhD, RN, FAAN, the Chair of her Dissertation Committee and Ronald C. Serlin, PhD, the Secondary Advisor for their conceptual contributions in their respective substantive areas. The first author also thanks Diana J. Wilkie, PhD, RN, FAAN, her research Faculty Mentor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Patrick J. McGrath, OC, PhD, FRSC, FCAHS for their contribution with manuscript revisions.

Funding Support: The Funding for this work was made possible by the National Institute of Nursing Research-National Research Service Award (NINR-NRSA) grant: 1F31NR010820 (Principal Investigation: Miriam O. Ezenwa, PhD, RN) and R01DAO13686 (Principal Investigator: Michael Fleming, MD, MPH).

Contributor Information

Miriam O. Ezenwa, College of Nursing, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Michael F. Fleming, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Northwestern University, m-fleming@northwestern.edu.

REFERENCES

- Anda R, Williamson D, Jones D, Macera C, Eaker E, Glassman A, Marks J. Depressed affect, hopelessness, and the risk of ischemic heart disease in a cohort of U.S. adults. Epidemiology. 1993;4(4):285–294. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA, Hunkeler EM, Blasey CM, Lee J, Constantino MJ, Fireman B, Hayward C. Comorbid depression, chronic pain, and disability in primary care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(2):262–268. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. doi: 68/2/262 [pii] 10.1097/01.psy.0000204851.15499.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Mendes De Leon CF, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Racial differences in perceived discrimination in a community population of older blacks and whites. J Aging Health. 2004;16(3):315–337. doi: 10.1177/0898264304264202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernabei R, Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, Landi F, Gatsonis C, Mor V. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(23):1877. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, O’Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Usherwood T, Westlake L. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. Bmj. 1992;305(6846):160–164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen I, Kurz J, Pasanen M, Faselis C, Panda M, Staton LJ, Cykert S. Racial differences in opioid use for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):593–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintron A, Morrison RS. Pain and ethnicity in the United States: A systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(6):1454–1473. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Baez L, Loehrer P, Pandya KJ. Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(9):813–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-9-199711010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, Edmonson JH, Blum RH, Stewart JA, Pandya KJ. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):592–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillie KS, Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT. Quality of life associated with daily opioid therapy in a primary care chronic pain sample. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(2):108–117. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.02.070144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty CJ. Bad faith and victim-blaming: the limits of health promotion. Health Care Anal. 1993;1(2):111–119. doi: 10.1007/BF02197104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn SL. Hopelessness as a response to physical illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37(2):148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson SA, Goldberg DE, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Pukkala E, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. Hopelessness and risk of mortality and incidence of myocardial infarction and cancer. Psychosom Med. 1996;58(2):113–121. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Salonen R, Salonen JT. Hopelessness and 4-year progression of carotid atherosclerosis. The Kuopio Ischemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17(8):1490–1495. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.8.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezenwa MO, Ameringer S, Ward SE, Serlin RC. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain management in the United States. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(3):225–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, Feagin JR. THE CONTINUING SIGNIFICANCE OF RACE: ANTIBLACK DISCRIMINATION IN PUBLIC PLACES. American Sociological Review. 1991;56(1):101. [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(3):295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Franks P. Does psychological distress contribute to racial and socioeconomic disparities in mortality? Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(12):1805–1809. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Balousek SL, Klessig CL, Mundt MP, Brown DD. Substance use disorders in a primary care sample receiving daily opioid therapy. J Pain. 2007;8(7):573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.02.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredheim OM, Kaasa S, Fayers P, Saltnes T, Jordhoy M, Borchgrevink PC. Chronic non-malignant pain patients report as poor health-related quality of life as palliative cancer patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2008;52(1):143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goertz CMH. Measuring functional health status in the chiropractic office using self-report questionnaires. Topics in Clinical Chiropractic. 1994;1(1):51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Green CR, Baker TA, Smith EM, Sato Y. The effect of race in older adults presenting for chronic pain management: a comparative study of black and white Americans. J Pain. 2003;4(2):82–90. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho M-J, LaFleur J. The treatment outcomes of pain survey (TOPS): a clinical monitoring and outcomes instrument for chronic pain practice and research. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2004;18(2):49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim SA, Burant CJ, Siminoff LA, Stoller EP, Kwoh CK. Self-assessed global quality of life: a comparison between African-American and white older patients with arthritis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(5):512–517. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00501-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research: Institute of Medicine. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MS, Lumley MA, Leisen JC. The relationships of cognitive coping and pain control beliefs to pain and adjustment among African-American and Caucasian women with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11(2):80–88. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpman RR, Del Mar N, Bay C. Analgesia for emergency centers’ orthopaedic patients: does an ethnic bias exist? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(334):270–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause MR, Serlin RC, Ward SE, Rony RY, Ezenwa MO, Naab F. Testing mediation in nursing research: beyond Baron and Kenny. Nurs Res. 2010;59(4):288–294. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dd26b3. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181dd26b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N. Racial and gender discrimination: risk factors for high blood pressure? Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(12):1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90307-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ. The association between perceived provider discrimination, healthcare utilization and health status in racial and ethnic minorities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(3):330–337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Lackland DT, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF. Perceived discrimination and blood pressure in older African American and white adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(9):1002–1008. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marascuilo LA, Levin JR. Multivariate statistics in the social sciences: A researcher’s guide. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DD. Gender and ethnic stereotyping and narcotic analgesic administration. Res Nurs Health. 1994;17(1):45–49. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01310.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng B, Dimsdale JE, Rollnik JD, Shapiro H. The effect of ethnicity on prescriptions for patient-controlled analgesia for post-operative pain. Pain. 1996;66(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)02955-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Debb S, Blitz D, Choi SW, Cella D. Racial/Ethnic differences in the health-related quality of life of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(5):488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren XS, Amick BC, Williams DR. Racial/ethnic disparities in health: the interplay between discrimination and socioeconomic status. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(2):151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N, Corrigan PW, Powell K, Rajah A, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, Batia K. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: II. Emotional stress responses, coping behavior and outcome. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;110(1-3):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.005. doi: S0920-9964(09)00035-8 [pii] 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust G, Nembhard WN, Nichols M, Omole F, Minor P, Barosso G, Mayberry R. Racial and ethnic disparities in the provision of epidural analgesia to Georgia Medicaid beneficiaries during labor and delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(2):456–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schouten HJ. Combined evidence from multiple outcomes in a clinical trial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00238-9. doi: S0895-4356(00)00238-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel BA, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among african american women in detroit: results from a longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serlin RC, Harwell MR. More powerful tests of predictor subsets in regression analysis under nonnormality. Psychol Methods. 2004;9(4):492–509. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.492. doi: 2004-21445-007 [pii] 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo-Sarver JH, Dawson NV, Hinze SW, Cydulka RK, Wigton RS, Albert JM, Baker DW. The effect of race/ethnicity and desirable social characteristics on physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioid analgesics. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(11):1239–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2004;5(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, Goe L. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(1):11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. Jama. 1993;269(12):1537–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp DA, Curtis Nickel J, Landis JR, Wang YL, Knauss JS. Predictors of quality of life and pain in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: findings from the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort Study. BJU Int. 2004;94(9):1279–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuzun EH. Quality of life in chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21(3):567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SE, Hernandez L. Patient-related barriers to management of cancer pain in Puerto Rico. Pain. 1994;58(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-economic Status, Stress and Discrimination. Health and socio-economic position. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby SG, Hailey BJ, Wheeler LC. Pain Patient Profile: a scale to measure psychological distress. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(10):1300–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]