Abstract

The cyclic prodigiosins are an important family of bioactive natural products that continue to be the subject of numerous structural, synthetic and biosynthetic studies. In particular, the structural assignments of the isomeric cyclic prodigiosins butylcycloheptylprodigiosin (BCHP) and streptorubin B have been cause for significant confusion. Herein, we report detailed studies regarding the Electron Impact (EI) mass spectra of synthetic BCHP and streptorubin B that have allowed us to distinguish the two compounds in the absence of quality historical isolation NMR data. Based upon these fragmentation differences, the status of BCHP as a natural product is challenged. The proposed mechanism of fragmentation is supported by the EI mass spectra of synthetic pentyl-chain analogues of BCHP and streptorubin B, X-ray crystallography, and DFT calculations. Elimination of BCHP from the prodigiosin family supports a proposed evolutionary hypothesis for the surprising biosynthesis of cyclic prodigiosins.

The prodigiosins are a family of bacterially-produced natural products which possess a defining tripyrrolic core.1 This tripyrrolic core is believed to be responsible for the wide range of interesting properties that the prodigiosins display, such as anion transport, radical generation, cation-binding, and protein-binding.2 These physical properties are further responsible for the potentially useful biological activities that the prodigiosins display, including immunosuppressive, anti-cancer, and anti-parasitic activities.3 A prodigiosin-inspired medicinal chemistry program at Gemin X led to the development of a synthetic small-molecule proapoptotic factor that is currently in multiple phase I and II clinical trials for the treatment of a variety of cancers.4

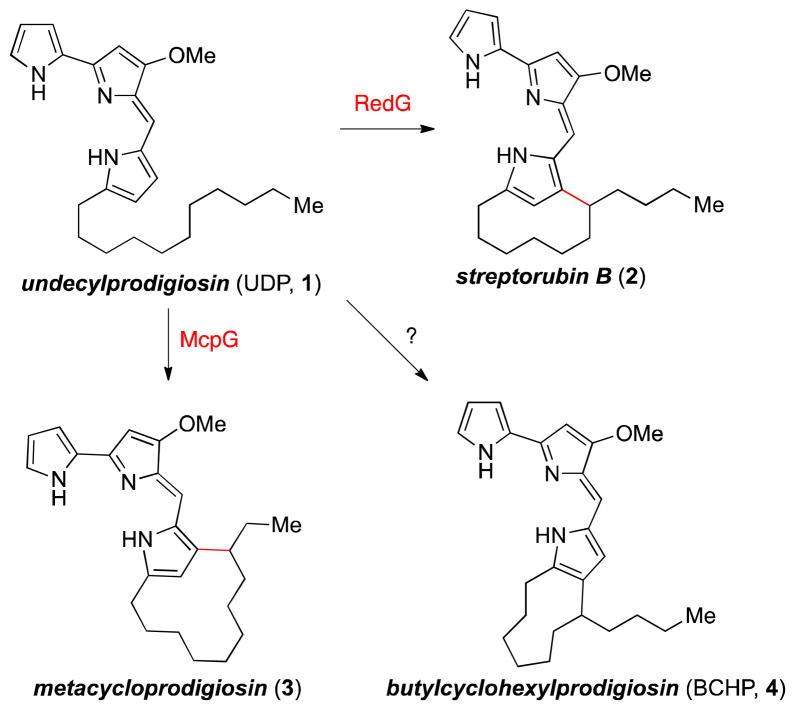

Bacteria biosynthesize pyrrolophane prodigiosins such as streptorubin B (2) and metacycloprodigiosin (3) through a Rieske-oxygenase (RedG or McpG) mediated radical cyclization from a common linear precursor, undecylprodigiosin (UDP, 1).5 These oxidative cyclizations are remarkable given the high degree of strain present within the products, leading us to speculate about the impact of the structural differences between UDP (1) and its cyclized products (i.e., 2 and 3). We hypothesized that the evolutionary purpose of this additional cyclization step may be due to advantageous enforcement of the geometry necessary for anion-or cation-binding (Figure 2).

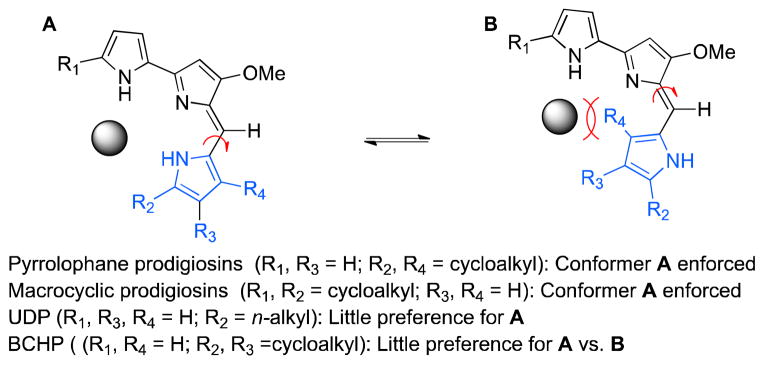

Figure 2.

Enforced conformations of cyclic prodigiosins

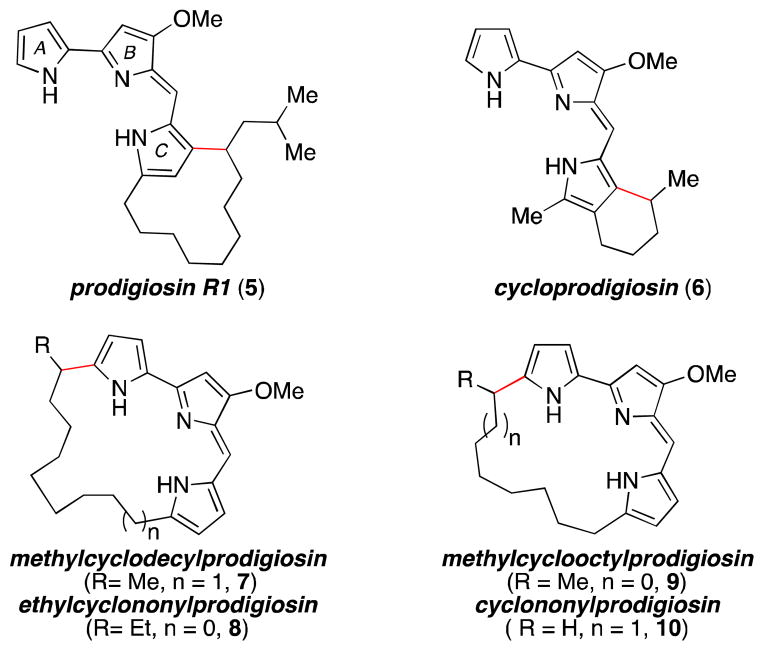

For the pyrrolophanes streptorubin B (2) and metacycloprodigiosin (3) cyclization introduces a source of conformational bias that is not present within UDP (1), which should lead to a predisposition for anion- or cation-binding (i.e., A vs. B, Figure 2).6 In fact, each cyclic prodigiosin so far discovered has possessed this conserved structural characteristic, introduced by either cyclization to C4 of the C-ring pyrrole or to C5 of the distal A-ring pyrrole (Figure 3).7

Figure 3.

Conserved structural trends for cyclic prodigiosins

Therefore, the appearance of butylcycloheptylprodigiosin (BCHP, 4) as an apparent natural product is intriguing, as this molecule would not appear to provide a significant conformational (and, hence, evolutionary) advantage over its likely linear progenitor, (i.e., UDP, 1). Amongst all known cyclic prodigiosin structures, BCHP (4) stands alone in this respect, which led us to reconsider its assignment as an actual natural product.

Historically, there has been some significant confusion as to whether BCHP is a natural product or not. The structure 4 was first proposed for a pink pigment isolated from Streptomyces sp. Y-42 and S. rubrireticuli by Gerber in 1975,8 but she reassigned the structure of this compound to that of 2 (i.e., streptorubin B) in 1978.9 In 1985, Floss and coworkers assigned the structure 4 to a pink pigment they isolated from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2).10 Given that Gerber had reassigned the structure of the pink pigment she isolated from 4 to 2, there was some doubt regarding the actual structure of Floss’s pink pigment. To provide insight into this quandry, Fürstner and coworkers synthesized BCHP (4) in 2005, and concluded that BCHP (4) was a natural product distinct from streptorubin B (2).11 They came to this conclusion based on comparisons between their NMR data and that of the authentic pigment, despite commenting that the authentic spectra was not entirely pure. Reeves supported this conclusion in his 2007 manuscript.12 Following these synthetic studies, Challis and coworkers reported the isolation of a cyclic prodigiosin from S. coelicolor M511 [a prototrophic derivative of S. coelicolor A3(2) lacking plasmids and the ability to produce actinorhodin] and identified it as streptorubin B (2), not BCHP (4).13 The findings by Challis are at odds to the report by Floss, and the subsequent confirmation of the BCHP structure by both Fürstner and Reeves. However, given that the organism Challis and coworkers studied was not exactly the same as the one Floss isolated the pink pigment from, there still remains room for doubt regarding the formulation of a definitive statement as to whether BCHP (4) is a natural product or not.

Because of our own interests in the synthesis, structure and biosynthesis of the cyclic prodigiosins,14 and in light of our evolutionary hypothesis (see above), we were motivated to reinvestigate the BCHP/streptorubin B question. The results of our structural investigations into BCHP (4) and its relationship to streptorubin B (2) are reported herein.

Results and Discussion

As part of our interest in the synthesis of prodigiosins, we had previously completed an enatioselective total synthesis of streptorubin B (2).14b Curiously, we observed that the EI mass spectrum of streptorubin B (2) matched the EI mass spectrum of the pink pigment isolated by Floss (i.e., BCHP, 4).15 While streptorubin B (2) and BCHP (4) bear some structural resemblance to one another, it seemed unlikely to us that they would have identical fragmentation patterns. We suspected that the strained meta-fusion of the pyrrolophane core of streptorubin B (2) would provide a characteristic fragmentation pattern that would be distinct from the ortho-linked pyrrole core of BCHP (4), and that perhaps a detailed analysis of mass spectra of the two compounds might finally answer the BCHP/streptorubin B question for good.

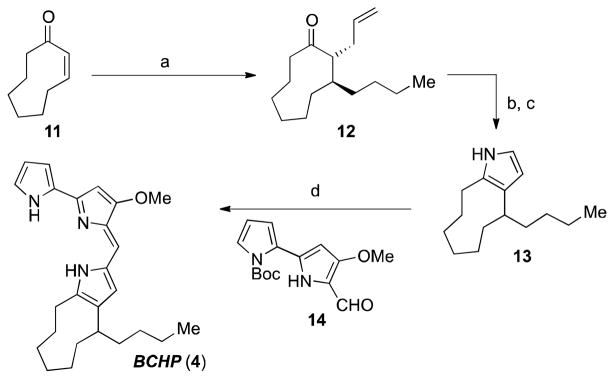

First, we sought to design a short synthesis of BCHP (4) that would quickly provide us with the material we needed. Previously, our research group had synthesized the pyrrolophane prodigiosins, metacycloprodigiosin (3), prodigiosin R1 (5) and streptorubin B (2),14 and due to the ease with which we were able to prepare 2 using a late-stage “biomimetic” condensation16 we sought to employ a similar strategy in the preparation of BCHP. Our synthesis was initiated with a one-pot conjugate-addition/Tsuji–Trost allylation17 on cyclononen-2-one (11) to afford compound 12 as a single diastereomer (Scheme 1). Subjecting the resulting alkene (i.e., 12) to Lemieux–Johnson oxidation18 conditions afforded a 1,4-dicarbonyl, which underwent smooth Paal–Knorr condensation19 with ammonium acetate to provide ortho-substituted pyrrole 13. A one-step condensation/deprotection sequence between pyrrole 13 and bispyrrole-aldehyde 1420 cleanly afforded the desired compound 4 as either the free base or the hydrochloride salt depending on isolation conditions (4 steps from 11, 49% overall yield).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of BCHP (5)

Reagents and Conditions a) n-BuMgCl, CuBr•DMS (20 mol%), −40 °C; then allylBr, Pd(PPh3)4 (10 mol%), 85%; b) OsO4 (3 mol%), NaIO4, EtOAc/H2O, 73%; c) NH4OAc, MeOH, reflux 98%; d) HCl, 14, then; NaOMe, MeOH, 80%.

NMR spectroscopic data (1H NMR, 13C NMR) of 4 were identical to those reported by both Fürstner11 and Reeves12 for synthetic BCHP (4), but there were discrepancies between our 1H NMR data and that of the 1H NMR spectrum of the authentic pigment.15 Although the spectrum of synthetic BCHP (4) and the authentic spectrum had some similar features, comparisons to streptorubin B (2) were likewise similar. Based upon NMR data alone, and in contrast to previous findings,11,12 we do not believe a definitive conclusion can be made as to whether BCHP is a natural product or not.

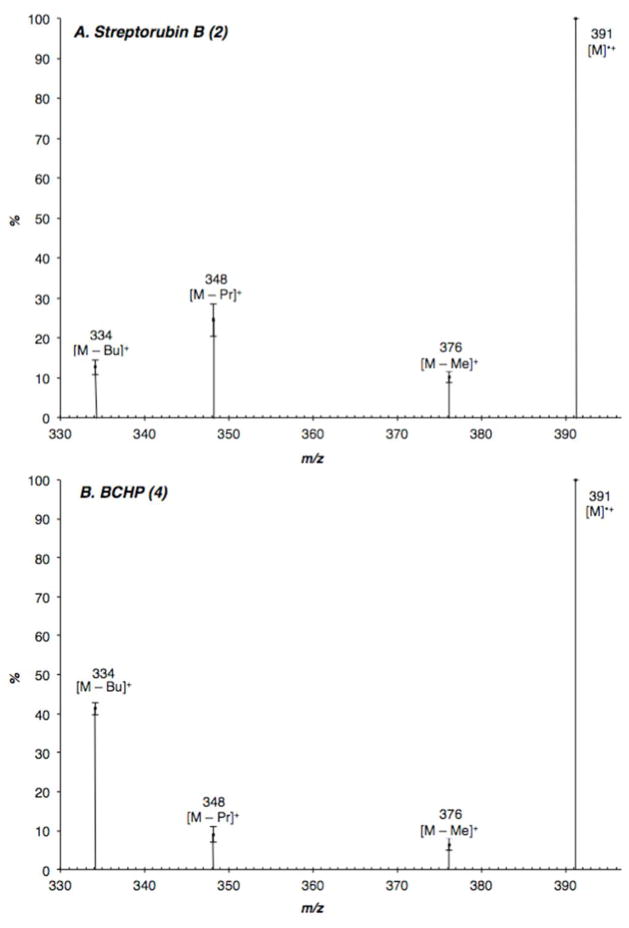

While the NMR data were not convincing, the electron impact (EI) mass spectra of synthetic BCHP (4) and streptorubin B (2) were, as we had hoped, characteristically distinct.21 Direct probe of the HCl salts of BCHP and streptorubin B revealed idiosyncratic differences in the % abundance of early fragments from the parent ion [M]+•, m/z 391 (expanded section shown in Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Higher molecular weight fragments within electron impact mass spectra of: A. Streptorubin B (2); and B BCHP (4). Error bars show one standard deviation of measured value from five separate runs.

We noted a reproducible (n = 5) pattern of the relative abundance between the m/z 376 [M – CH3]+, m/z 348 [M – C3H7]+, and m/z 334 [M – C4H9]+ ions. Most striking was the change in relative abundance of the ions from the loss of propyl and butyl for each molecule. For BCHP (4), [M – C3H7]+ and [M – C4H9]+ were 9% and 41%, respectively. In contrast, for streptorubin B (2) [M – C3H7]+ and [M – C4H9]+ were 25% and 13%, respectively. Thus, BCHP (4) undergoes more favorable loss of butyl relative to propyl, while for streptorubin B (2) the opposite is true. The EI mass spectra reported for the pink pigments isolated by both Gerber8 and Floss10 display the same characteristic relative abundance of these key fragment ions in 70 eV EI-MS as streptorubin B (2) and not BCHP (4). Thus, in light of this data we concluded that the pink pigment isolated by Floss was in fact streptorubin B (2) and not BCHP (4). Based upon this information we conclude that butylcycloheptylprodigiosin (4) is, at this time, not a known natural product.

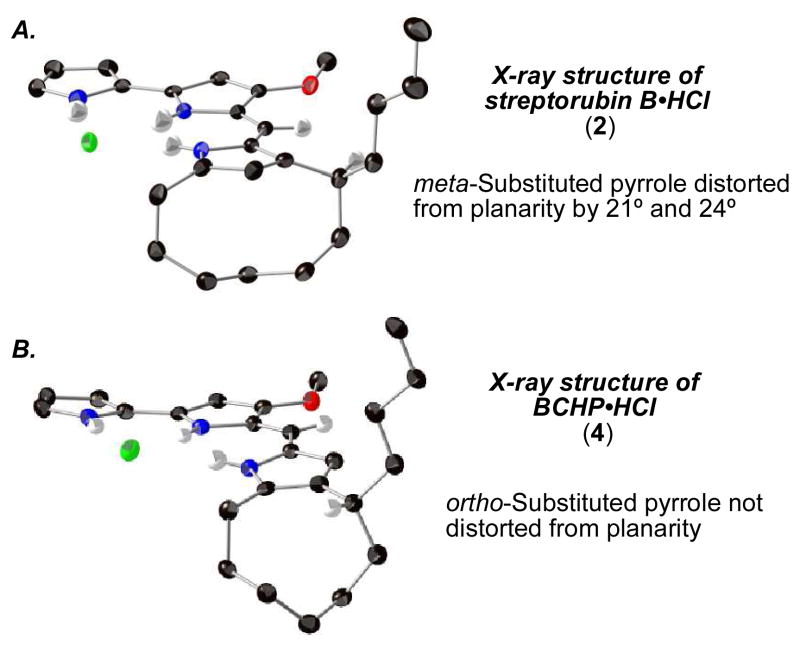

We were curious as to why the relative abundances of the peaks corresponding to the loss of propyl and butyl were so different between streptorubin B (2) and BCHP (4). These two compounds are constitutional isomers wherein the point of attachment of the undecyl-hydrocarbon chain to the pyrrole differs: ortho for BCHP (4) and meta for streptorubin B (2). This seemingly trivial difference has dramatic effects on the corresponding structures, however. Specifically, the strained meta-cyclophane nature of streptorubin B’s ten-membered ring leads to significant distortion of the σ-bonds attached to the pyrrole nucleus. An X-ray structure we obtained of 2•HCl revealed substantial pyramidalization of the pyrrole carbons attached to the meta-bridge (between 21° and 24° from planarity) (see Figure 5).14b, 22 Such deformation is not present within the X-ray structure of 4•HCl that we were also able to obtain, since the nine-membered ring is ortho-fused and does not suffer the additional strain that meta-fusion engenders.22

Figure 5.

A. X-ray crystal structure of streptorubin B•HCl (2). B. X-ray crystal structure of BCHP•HCl (4).

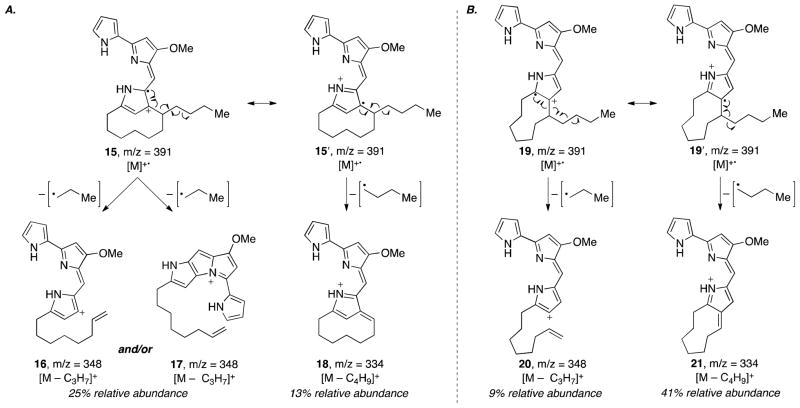

Based upon this structural analysis, we hypothesized that cleavage of the meta carbon–carbon bond adjacent to the butyl sidechain within streptorubin B (2) would be more favorable during fragmentation of the molecular ion (i.e., 15) under EI conditions for mass spectrometry (Figure 6). Following this logic, we rationalized the higher abundance of m/z 348 [M – C3H7]+ (i.e., 16 or 17) relative to m/z 334 [M – C4H9]+ (i.e., 18). Loss of propyl from [M]+•15, shown in Figure 6, with concomitant rupture of the cyclophane ring leads to fragment 16 or 17, which due to strain release should be kinetically more favorable than the corresponding loss of butyl to form 18 from [M]+•15′. In contrast to streptorubin B (2), BCHP (4) undergoes a more favorable loss of butyl from [M]+•19′ to generate fragment 21. The driving force for scission of the ortho-linked nine-membered ring within 4 is reduced relative to 2, and therefore loss of propyl to produce 20 occurs with lower frequency.

Figure 6.

Mechanistic hypothesis for electron impact mass spectrometry fragmentations. A. Streptorubin B; B. BCHP

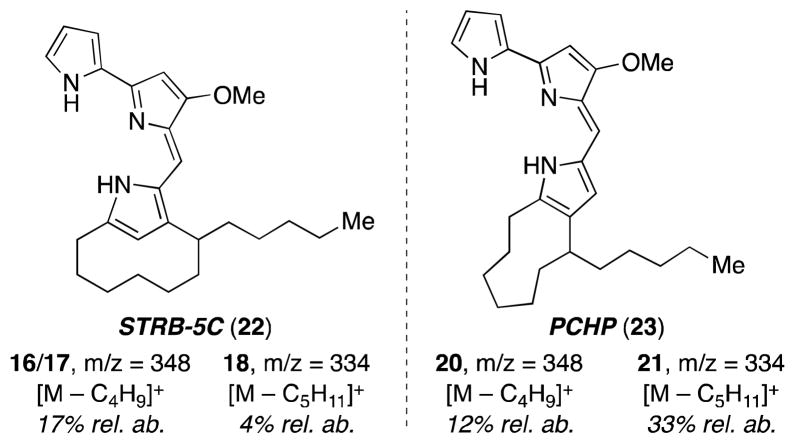

We provided evidence that these ions in the EI mass spectra are derived specifically from fragmentation of the aliphatic sidechains by synthesizing pentyl homologs of streptorubin B and BCHP, namely STRB-5C (22) and PCHP (23).23 For each pentyl homolog we observed the same trend of fragmentation patterns using EI mass spectrometry as we had seen for the butyl series (Figure 4).

Loss of butyl was now favored for the streptorubin B homolog 22 (i.e., to form 16/17), while loss of pentyl was favored for the BCHP homolog 23 (i.e., to form 21).

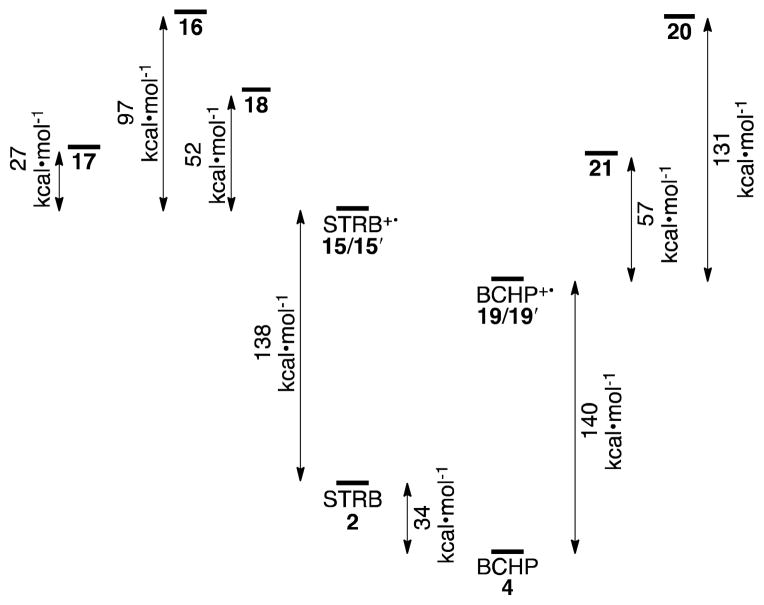

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to gain some insight into the stability of these proposed molecular fragments. Structure optimizations using Q-Chem24 at B3LYP-6-31+G* level of theory provided the relative energies shown in Figure 5. As expected, the ground state energy minimizations indicated that streptorubin B (2) was higher in energy than BCHP (4), most likely due to aforementioned ring strain induced by the meta-bridge. This energy difference is reflected in the relative energies of the radical–cation molecular ions for each compound (i.e., 15/15′ and 19/19′). Loss of butyl from each molecular ion produces fragments 18 and 21 through a process that is endothermic by 52 and 57 kcal•mol−1, respectively. The corresponding fragmentations of each molecular ion to generate ring-opened ions 16 and 20 were calculated as being endothermic by 98 and 131 kcal•mol−1, respectively. For the case of BCHP (4), the thermodynamic difference in energy between 20 and 21 is reflected in the observed relative abundances of each ion in the EI mass spectrum. For streptorubin B (2), however, the energy difference between the corresponding fragments (i.e., 16 and 18) is not reflected in their relative abundance. We considered the cyclized structure 17 in our analysis, which intuitively appeared to be a better candidate fragment than the sp2-cation 16. Indeed, energy minimization of 17 showed it was significantly more stable than both 16 and 18, and was only 27 kcal•mol−1 higher in energy than the molecular ion 15/15′. The analogous cyclized structure cannot form from BCHP (4) due to geometric constraints, and it is therefore tempting to conclude that the higher abundance of the m/z 348 ion in the mass spectrum of streptorubin B (2) is due to the formation of stable fragment 17. We conclude that a combination of this thermodynamic driving force, coupled to the facile kinetic scission of the strained meta-pyrrolophane ring system within streptorubin B (2), accounts for the observed fragmentation patterns.

Conclusions

Our studies into the structural assignment of BCHP (4) were motivated by a proposed evolutionary hypothesis for the biosynthesis of the cyclic prodigiosins. These studies, which involved detailed mass spectral analysis of BCHP (4) and streptorubin B (2), have concluded that BCHP (4) was not the compound isolated from S. coelicolor A3(2) by Floss in 1985. This species was in fact streptorubin B (2), as indicated by identical EI-MS fragmentation patterns; a finding that supports the 2008 isolation study by Challis and coworkers.25 If BCHP (4) was a natural product produced by S. coelicolor A3(2) there should be a second Rieske-oxygenase encoded within its genome that is analogous to the recently determined sequence that encodes the conversion of undecylprodigiosin (1) into streptorubin B (2), i.e., redG.5,25 No such homologous sequence has been found within S. coelicolor A3(2).26 Furthermore, constitutive expression of redG in an engineered mutant of S. veneuzelae (a bacteria that does not contain the prodigiosin gene cluster) converts undecylprodigiosin (1) into streptorubin B (2) with no evidence of BCHP (4) production.5 The combination of our mass spectral comparisons, with this genetic and biochemical data, provides overwhelming evidence that BCHP (4) is not a natural product produced by S. coelicolor. Further studies of these fascinating molecules will hopefully provide insights into the as yet unanswered questions surrounding their tightly regulated biosynthesis and their possible evolutionary purpose. Studies regarding the difference in anion-and cation-binding properties of the naturally occuring cyclic vs. acyclic prodigiosins, which are ongoing in our laboratories, will shine light on these questions. The results of these studies will be reported in due course.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

All reactions were carried out under a nitrogen atmosphere in flame-dried glassware with magnetic stirring unless otherwise stated. THF and CH2Cl2 were purified by passage through a bed of activated alumina. Reagents were purified prior to use unless otherwise stated. Purification of reaction products was carried out by flash chromatography using EM Reagent silica gel 60 (230–400 mesh). Analytical thin layer chromatography was performed on EM Reagent 0.25 mm silica gel 60-F plates. Visualization was accomplished with UV light and anisaldehyde followed by heating. Film infrared spectra were recorded using a BioRad Excalibur and a BioRad FTS-60. Diamond infrared spectra were recorded using a Thermo Mattson ATR. 1H-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advance III 500 (500 MHz) spectrometer and are reported in ppm using solvent as an internal standard (CDCl3 at 7.26 ppm) or tetramethylsilane (0.00 ppm). Two-dimensional NMR experiments were run on a Bruker Advance III 500 (500 MHz). Data are reported as: app = apparent, obs = obscured, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, h = hextet, sep = septet, o = octet, m = multiplet, b = broad; integration; coupling constant(s) in Hz. Proton-decoupled 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Advance III 500 (125 MHz) spectrometer and are reported in ppm using solvent as an internal standard (CDCl3 at 77.00 ppm). Mass spectral data were obtained on an Agilent 6210 Time-of-Flight LC/MS and a Waters GC-TOF Premier High Resolution Time of Flight MS with an EI source.

A: Synthesis of ortho-Butylcycloheptylprodigiosin (BCHP)

trans-2-Allyl-3-(n-butyl)-cyclononanone (12)

To a stirred suspension of CuBr·DMS (30 mg, 0.14 mmol) in THF (3 mL) at −40 °C was added n-BuMgCl (1.5M in THF, 528 μL, 1.1 eq). The suspension was stirred for 10 min before cyclonon-2-enone (100 mg, 0.72 mmol) was added dropwise in THF (1.5 mL). The solution became homogenous and bright yellow before turning heterogenous and black upon complete addition. After 45 min. freshly distilled allyl bromide (182 μL, 2.16 mmol) was quickly added, followed by addition of solid Pd(PPh3)4 (83 mg, 0.07 mmol). The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stir for an additional 6 hours. The solution was quenched with aq. AcOH (2 mL) and diluted with Et2O (3 mL). The organic phase was separated, and the aqueous layer extracted with Et2O (3 × 5 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried with MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (20% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound (145 mg, 85%). IR (neat) 2955, 2929, 2873, 1703, 1476, 1356, 995, 914; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 5.59 (dddd, 1H, J = 17.1, 10.0, 8.1, 6.1 Hz), 4.92 (dd, 1H, J= 17.1, 1.1 Hz), 4.88 (dd, 1H, J = 10.0, 1.1 Hz), 2.47 (m, 2H), 2.29 (m, 1H), 2.14 (m, 2H), 1.82 (m, 1H), 1.62 (m, 1H), 1.54 (m, 1H), 1.48-1.16 (m, 14H), 0.83 (t, 3H, J = 7.2 Hz); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) 218.6, 136.2, 116.7, 57.9, 42.5 (br), 39.2, 35.7, 32.4, 28.4, 27.3, 24.0, 23.5, 23.4, 23.0, 22.9, 14.1; HRMS (EI+): Exact mass calcd for C16H28O [M+], 236.2140. Found 236.2148.

trans-2-(Acetaldehyde)-3-(n-butyl)-cyclononanone (24)

To a stirred solution of allylcyclononanone 6 (38 mg, 0.16 mmol) in EtOAc (0.75 mL) was added NaIO4 (76 mg, 0.35 mmol), OsO4 (2.5 wt% in t-BuOH, 204 mg, 0.016 mmol), and H2O (0.75 mL). The solution was stirred vigorously overnight before being partitioned between Et2O (3 mL) and brine (3 mL). The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer extracted with Et2O (3 × 3 mL). The combined organic layers were dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (20% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound (28 mg, 73%). IR (neat) 2932, 2872, 2721, 1723, 1702, 1467, 1382, 1240, 1043; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 9.69 (s, 1H0, 2.98 (m, 2H0, 2.79 (ddd, 1H, J = 14.8, 7.3, 5.6 Hz), 2.68 (m, 1H), 2.56 (m, 1H), 1.80 (m, 2H), 1.70 (m, 1H), 1.59 (m, 1H), 1.53-1.16 (m, 14H), 0.88 (t, 3H, J = 8.1 Hz); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) 201.2, 50.4, 46.8, 45.7, 40.9, 33.3, 31.6, 28.2, 27.3, 26.5, 25.2, 24.7, 23.6, 22.9, 22.6, 14.1; HRMS (APPI+): Exact mass calcd for C15H28O2 [M+H+], 239.2010. Found 239.2010.

3-(n-Butyl)-ortho-cyclononylpyrrole (13)

To a solution of dicarbonyl 24 (65 mg, 0.273 mmol) in dry MeOH (3 mL) was added azeotropically dried NH4OAc (210 mg, 2.73 mmol). The solution was refluxed (65°C) for 30 min before being cooled to room temperature and diluted with hexanes (7 mL). The solution was directly subjected to flash column chromatography (20% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound as a clear oil (59 mg, 98%). IR (neat) 3377, 2923, 2853, 1686, 1457, 1082; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.65 (br s, 1H), 6.65 (t, 1H, J = 2.66 Hz), 5.96 (t, 1H, J = 2.8 Hz), 2.70 (m, 1H), 2.66 (m, 2H), 1.87 (m, 1H), 1.66-1.28 (m, 14H), 1.03 (m, 1H), 0.89 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) 129.6, 122.8, 115.0, 106.2, 37.16, 36.7, 35.8, 30.5, 27.7, 27.3, 27.0, 26.9, 23.4, 22.9, 14.2; HRMS (APPI+): Exact mass calcd for C15H26N [M+H+], 220.2060. Found 220.2067.

ortho-Butylcycloheptylprodigiosin (BCHP, 4)

To a solution of pyrrole 14 (7.5 mg, 0.34 mmol) and bispyrrole aldehyde 820 (12 mg, 1.2 eq) in MeOH (1 mL) was added dry HCl in MeOH (1 M, 34 μL, 1 eq, freshly prepared from AcCl and MeOH) at 0°C. The solution immediately turns a deep red color, and is allowed to stir for 1h 15 min. A suspension of NaOMe (36 mg) in MeOH (0.66 mL) was then added, causing the solution to turn dark orange. The reaction was monitored by LCMS, and after 1 hr, the solution was poured into ether (10 mL), washed with brine (5 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. The organic phase was concentrated en vacuo and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient: 5 to 20% EtOAc in hexanes with 2% NEt3, silica gel) to afford the title compound as a dark orange solid (10.6 mg, 80%). IR (neat) 3112, 2922, 2853, 1624, 1555, 1467, 1378, 1346, 1287, 1233; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.61 (s, 1H), 6.59 (s, 1H), 6.25 (s, 1H), 6.09 (t, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz), 6.01 (s, 1H), 3.88 (s, 3H), 2.46 (m, 1H), 2.16 (br s, 2H), 1.56 (m, 1H), 1.48-1.40 (m, 4H), 1.23 (m, 2H), 1.18-1.04 (m, 7H), 0.75 (t, 3H, J = 7.6Hz), 0.66 (br m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD2Cl2) 169.4, 159.8, 143.2, 138.8, 129.1, 128.3, 128.1, 122.5, 118.9, 116.5, 112.6, 110.5, 95.9, 58.9, 38.1, 37.0, 36.0, 30.6, 28.2, 28.1, 27.6 (2), 23.3, 23.1, 14.2; HRMS (ESI+): Exact mass calcd for C25H34N3O [M+H+], 392.2696. Found 392.2703.

The HCl salt of 4 was obtained using the same procedure but by purifying the product by silica gel chromatography under different conditions (gradient: CHCl3 to 1% MeOH/CHCl3, silica gel); (11 mg 4·HCl from 6 mg 7, 95%). IR (neat) 3156, 2953, 2869, 1632, 1602, 1572, 1346, 1268, 1115, 962; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): 12.80 (s, 1H), 12.63 (s, 2H), 7.25 (s, 1H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.65 (d, 1H, J = 3 Hz), 6.37 (s, 1H), 6.10 (s, 1H), 4.03 (s, 3H), 3.35 (m, 1H), 2.76 (m, 2H), 2.15 (m, 1H), 1.71 (m, 2H), 1.63-1.58 (m, 4H), 1.45-1.38 (m, 4H), 1.30-1.22 (m, 4H), 1.14 (m, 1H), 0.88 (t, 3H, J = 7.8 Hz); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) 165.9, 153.0, 147.8, 132.5, 127.1, 126.6, 125.8, 122.4, 120.8, 117.2, 116.2, 111.8, 92.9, 58.6, 37.0, 36.6, 35.9, 30.1, 27.3, 27.1, 26.9, 26.6, 23.6, 22.7, 14.1.

B. Synthesis of Streptorubin B–5C (STRB–5C)

trans-2-((Z)-Hept-1-enyl)cyclohexanol (25)

To a solution of heptanedial (0.26 g, 2 mmol) in dichloromethane (20 mL) was added (rac)-proline (23 mg, 0.2 mmol) at room temperature. The heterogenous mixture was stirred for 15 hours, after which the solution became clear and homogenous. To a heterogenous solution of hexyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (1.11 g, 2.6 mmol) in THF (20 mL) at 0 °C was added sodium hexamethyldisilazane (2.6 mL, 2.6 mmol, 1 M in THF), upon which the solution turned bright orange. The ylide solution was allowed to stir for 1h 20 min prior to addition of aldehyde solution via cannula at 0 °C upon which the solution turned cloudy and white. After 3h, the reaction mixture was quenched with saturated NH4Cl (20 mL), and the ether layer separated. The aqueous/halogenated layers were extracted with Et2O (3 × 20 mL), washed with brine (60 mL) and dried with NaSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (10% Et2O in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound as a 5:1 mixture of diastereomers (260 mg, 66%). IR (neat) 3430, 2998, 2927, 2856, 1449, 1076 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.63 – 5.55 (dt, J = 11.2, 7.4 Hz, 1H), 5.21 – 5.12 (ddt, J = 11.3, 9.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 3.24 – 3.15 (m, 1H), 2.28 – 2.17 (dtd, J = 12.9, 9.8, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 2.14 – 1.98 (m, 4H), 1.86 – 1.81 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 1.81 – 1.74 (dt, J = 8.1, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 1.69 – 1.56 (m, 4H), 1.45 – 1.19 (m, 13H), 1.19 – 1.07 (tdd, J = 13.3, 11.3, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 0.92 – 0.85 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 133.47, 131.55, 73.83, 44.85, 33.48, 31.51, 31.45, 29.62, 27.79, 25.26, 24.85, 22.58, 14.08; HRMS (TOF EI+): Exact mass calcd for C13H24O [M+], 196.1827. Found 196.1812.

(Z)-2-(Hept-1-enyl)cyclohexanone (26)

To a solution of freshly distilled oxalyl chloride (75 μL, 0.86 mmol) in DCM (3 mL) at −78°C was added dropwise DMSO (70 μL, 0.99 mmol). The solution was stirred for 5 minutes, after which a solution of secondary alcohol 25 (140 mg, 0.71 mmol) in DCM (3 mL) was added. The solution was stirred for 20 minutes, followed by addition of iPr2NEt (0.618 mL, 3.55 mmol) dropwise. The solution was stirred for 10 minutes before being warmed to 0 °C in an ice bath. The solution was further stirred at 0 °C for 30 minutes, then poured into H2O (15 mL). The organic phase was collected, and the aqueous layer extracted with DCM (2 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography (10% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) afforded the title compound (92 mg, 67%): IR (neat) 2930, 2859, 1712, 1449, 1340, 1310, 1126 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.61 – 5.48 (m, 2H), 3.33 – 3.21 (dddd, J = 10.7, 7.7, 5.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 2.52 – 2.38 (dtd, J = 13.8, 4.3, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 2.38 – 2.25 (dddd, J = 14.1, 12.9, 7.1, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.11 – 1.82 (m, 5H), 1.82 – 1.56 (m, 3H), 1.46 – 1.18 (m, 7H), 0.95 – 0.83 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 211.52, 132.38, 126.38, 77.29, 77.23, 77.03, 76.78, 49.43, 41.77, 34.94, 31.49, 29.22, 27.75, 27.57, 24.44, 22.56, 14.07; HRMS (ESI): Exact mass calcd for C13H23O [M+H+], 195.1743. Found 195.1752.

trans-1-((E)-3-(Benzyloxy)prop-1-enyl)-2-((Z)-hept-1-enyl)cyclohexanol (27)

To a solution of (E)-1-benzyloxy-3-iodo-2-propene27 (96 mg, 0.35 mmol) in Et2O (4.5 mL) at −78 °C was added a solution of n-BuLi in hexanes (135 μL, 2.52 M). The mixture was allowed to stir for 1 minute prior to addition of ketone 26 (40 mg, 0.20 mmol) in Et2O (1.5 mL) at −78°C. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 30 minutes before being warmed to 0 °C and quenched with saturated NH4Cl solution (2 mL). The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer extracted with EtOAc (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with brine (20 mL), dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography (5–10% EtOAc in hexanes) afforded the title compound (49 mg, 72%): IR (neat) 3476, 3010, 2929, 2855, 1452, 1359, 1114, 1068, 973, 909 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.37 – 7.31 (m, 4H), 7.30 – 7.27 (dt, J = 6.2, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 5.77 – 5.71 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H), 5.44 – 5.37 (dd, J = 11.1, 7.1 Hz, 1H), 5.35 – 5.26 (m, 1H), 4.51 – 4.44 (m, 2H), 4.04 – 3.96 (m, 2H), 2.40 – 2.25 (ddd, J = 11.4, 9.7, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 2.04 – 1.89 (m, 2H), 1.78 – 1.41 (m, 7H), 1.35 – 1.20 (m, 7H), 0.94 – 0.80 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.16, 138.40, 130.98, 129.65, 128.41, 128.36, 127.77, 127.75, 127.56, 123.70, 73.07, 71.79, 70.49, 43.55, 38.04, 31.59, 29.42, 28.46, 27.78, 25.22, 22.62, 21.34, 14.12; HRMS (ESI): Exact mass calcd for NaC23H34O2 [M+Na+], 365.2451. Found 365.2447.

trans-(E)-3-(Benzyloxymethyl)-4-pentylcyclodec-5-enone (28)

To a stirring suspension of KH (12 mg, 0.3 mmol) in Et2O (4 mL) at 0 °C was added hexamethyldisilazane (63 μL, 0.3 mmol). The suspension was stirred for 30 minutes at room temperature prior to addition into a stirring solution of allylic alcohol 27 (50 mg, 0.15 mmol) and 18-crown-6 ether (79 mg, 0.3 mmol) in Et2O (5 mL) at 0 °C. The resulting yellow solution was stirred for 18 h at room temperature. The reaction was quenched with sat. NH4Cl solution (1 mL) and poured into H2O (5 mL). The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phases were dried (Na2SO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography on silica gel (3–15% EtOAc in hexanes) afforded the title compound (23 mg, 49%): IR (neat) 2928, 2857, 1704, 1496, 1361, 1090, 736 cm−1; (note: NMR spectra were significantly obscured, presumably due to alkene anisotropy) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.29 – 7.25 (m, 4H), 7.24 – 7.20 (td, J = 5.2, 4.1, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.44 – 4.96 (m, 2H), 4.55 – 4.40 (m, 2H), 3.64 – 3.22 (m, 2H), 2.44 – 2.09 (m, 5H), 2.00 – 1.77 (m, 2H), 1.72 – 1.55 (m, 1H), 1.45 – 1.11 (m, 8H), 1.07 – 0.92 (m, 1H), 0.92 – 0.68 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 128.37, 127.67, 33.45, 22.70, 14.16; HRMS (ESI): Exact mass calcd for NaC23H34O2 [M+Na+], 365.2451. Found 365.2443.

trans-3-(Hydroxymethyl)-4-pentylcyclodecanone (29)

To a solution of cyclodecanone 28 (23 mg, 0.07 mmol) in dry MeOH (3 mL) was added 10% Pd/C (7 mg). The flask was purged with H2, and the solution allowed to stir under a balloon of H2 at room temperature for 19 h and recharged with an additional 5 mg 10% Pd/C. After an additional 18 h the solution was filtered through celite, eluting with 25 mL ethyl acetate, and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography (20% EtOAc in hexanes) afforded the title compound (15 mg, 85%): IR (neat) 3417, 2925, 2857, 1698, 1469, 1045 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.74 – 3.66 (dd, J = 10.4, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.55 – 3.46 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.93 – 2.82 (m, 1H), 2.61 – 2.50 (ddd, J = 14.2, 10.4, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.50 – 2.41 (ddd, J = 15.1, 7.6, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 2.41 – 2.31 (tt, J = 13.8, 4.3 Hz, 2H), 2.10 – 1.96 (m, 1H), 1.95 – 1.85 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 1.76 – 1.57 (m, 2H), 1.57 – 1.47 (m, 2H), 1.46 – 1.14 (m, 14H), 0.92 – 0.82 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 215.86, 77.29, 77.24, 77.04, 76.78, 64.55, 43.44, 41.83, 40.96, 36.33, 32.13, 31.71, 28.51, 27.67, 25.58, 25.52, 24.27, 23.99, 22.69, 14.14; HRMS (ESI): Exact mass calcd for NaC16H30O2 [M+Na+], 277.2138. Found 277.2138.

trans-9-Oxo-2-pentylcyclodecanecarbaldehyde (30)

To a solution of keto-alcohol 29 (10 mg, 0.04 mmol) in DCM (2 mL) was added Dess–Martin periodinane (25 mg, 0.06 mmol). The solution was allowed to stir for 30 min under N2 atmosphere. The solution was diluted in ether, and concentrated to a small volume in vacuo. The residue was taken up in ether and washed with 1:1 0.5 M Na2S2O3/sat. NaHCO3 (10 mL), H2O (10 mL), and brine (10 mL). The aqueous layers were back-extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL), and the combined organic layers were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo. Purification by flash chromatography (20% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) afforded the title compound (10 mg, 99%): IR (neat) 2926, 2859, 2708, 1723, 1703, 1467 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.75 – 9.72 (s, 1H), 3.21 – 3.13 (dt, J = 9.7, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.91 – 2.80 (dd, J = 16.2, 9.8 Hz, 1H), 2.69 – 2.61 (dd, J = 16.2, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 2.59 – 2.46 (dtdt, J = 15.3, 11.7, 7.6, 3.9 Hz, 2H), 2.18 – 2.08 (tt, J = 8.2, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 2.08 – 1.94 (m, 1H), 1.77 – 1.66 (m, 1H), 1.56 – 1.20 (m, 16H), 0.92 – 0.79 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 213.24, 203.62, 52.02, 43.11, 37.15, 35.60, 32.01, 31.92, 28.77, 27.45, 26.18, 25.19, 23.80, 23.45, 22.59, 14.08; HRMS (ESI): Exact mass calcd for NaC16H28O2 [M+Na+], 275.1982. Found 275.1991.

2-Pentyl-10-azabicyclo[7.2.1]dodeca-1(11),9(12)-diene (31)

To a solution of dicarbonyl 30 (6 mg, 0.024 mmol) in anhydrous methanol (1 mL) was added dry NH4OAc (18 mg, 0.24 mmol). The stirred solution was heated at reflux at 65 °C for 40 minutes under N2 and cooled to room temperature. The reaction mixture was concentrated and subjected to flash chromatography (10% ethyl acetate in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound (6 mg, 99%): 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.81 – 7.56 (s, 1H), 6.46 – 6.39 (t, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.24 – 6.16 (dd, J = 2.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 2.69 – 2.58 (m, 1H), 2.50 – 2.34 (m, 2H), 1.79 – 1.59 (m, 4H), 1.53 – 1.36 (m, 2H), 1.34 – 1.23 (m, 7H), 0.92 – 0.85 (m, 6H), 0.76 – 0.63 (tdd, J = 14.0, 9.4, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 0.56 – 0.44 (dt, J = 12.8, 10.8 Hz, 1H), −1.80 – −2.05 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 132.54, 130.02, 114.64, 111.67, 41.73, 41.25, 33.78, 32.55, 32.25, 30.02, 29.79, 29.38, 27.73, 26.71, 22.74, 14.19; HRMS (ESI) Exact mass calcd for C16H28N [M+H+], 234.2216. Found 234.2218.

Streptorubin B–5C HCl (22)

To pyrrole 31 (4.3 mg, 0.018 mmol) and bispyrrole aldehyde 820 (6.4 mg, 0.022 mmol) under N2 atmosphere was added anhydrous MeOH (0.4 mL). To the stirred solution in a water bath (18 °C) was added a solution of HCl in MeOH (18 μL, 1 M, freshly generated from AcCl in MeOH) dropwise, upon which the solution turned a brilliant red. The solution was stirred for 1 h 15 min before addition of NaOMe in MeOH (25 μL, 25% wt solution), upon which the solution turned a dark brown. After 45 min the reaction mixture was poured into Et2O (5 mL) and washed with H2O (5 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (3 × 5 mL) and the combined organic layers were dried with Na2SO4. Two iterations of column chromatography (15–20% EtOAc in Hexanes, then CHCl3 to 3% MeOH/CHCl3, silica gel) afforded the natural product as the HCl salt, as a ca. 1:1 mixture of atropisomers, which upon mild heating in CHCl3 in a closed vessel equilibrated to a single atropisomer (7 mg, 90%). IR (neat) 3151, 2928, 2858, 1599, 1543, 1516, 1255 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.73 – 12.68 (s, 1H), 12.67 – 12.62 (s, 1H), 12.61 – 12.53 (s, 1H), 7.26 – 7.18 (td, J = 2.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.14 – 7.10 (s, 1H), 6.93 – 6.87 (m, 1H), 6.53 – 6.49 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 6.37 – 6.30 (dt, J = 4.3, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.13 – 6.07 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 4.05 – 3.97 (s, 3H), 3.37 – 3.28 (ddd, J = 12.9, 4.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 3.14 – 3.06 (ddt, J = 8.1, 5.6, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 2.59 – 2.49 (td, J = 12.3, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 1.96 – 1.89 (m, 1H), 1.87 – 1.68 (m, 3H), 1.56 – 1.51 (m, 1H), 1.41 – 1.30 (m, 7H), 1.29 – 1.22 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 4H), 1.21 – 1.08 (m, 3H), 0.97 – 0.73 (m, 8H), −1.48 – −1.60 (dt, J = 15.7, 8.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.38, 154.68, 150.62, 146.99, 126.66, 125.02, 122.37, 120.28, 116.74, 116.54, 112.54, 111.54, 92.71, 77.29, 77.24, 77.03, 76.78, 58.65, 38.92, 37.48, 32.10, 31.64, 31.24, 29.98, 29.72, 29.14, 27.91, 27.72, 25.45, 22.66, 14.13; HRMS (TOF EI+) Exact mass calcd for C25H33N3O [M+], 405.2991 Found 405.2748.

C. Synthesis of Pentylcycloheptylprodigiosin (PCHP)

trans-2-Allyl-3-(n-pentyl)-cyclononanone (32)

To a stirred suspension of CuBr·DMS (14 mg, 0.07 mmol) in THF (3 mL) at −40 °C was added n-PentMgBr (2.0 M in hexanes, 400 μL, 1.1 eq). The suspension was stirred for 10 min before cyclonon-2-enone (100 mg, 0.72 mmol) was added dropwise in THF (1.5 mL). The solution became homogenous and bright yellow before turning heterogenous and black upon complete addition. After 1 hour, freshly distilled allyl bromide (183 μL, 2.16 mmol) was quickly added turning the reaction mixture purple. After 10 min, a solution of Pd(PPh3)4 (173 mg, 0.15 mmol) in THF (7 mL) was added, turning the reaction a yellow/brown color. The reaction was then warmed to room temperature and let stir for an additional 3 hours. The solution was quenched with aq. AcOH (2 mL) and diluted with Et2O (10 mL). The organic phase was separated, and the aqueous layer extracted with Et2O (3 × 10 mL). The organic layers were combined, dried with Na2SO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (3% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound (167 mg, 93%). IR (neat) 2922, 1703, 1640, 1475, 1169, 1038, 914 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.76 – 5.56 (dddd, J = 16.4, 10.1, 8.1, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 5.05 – 4.96 (dq, J = 17.0, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 4.96 – 4.92 (dd, J = 10.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 2.62 – 2.46 (tdd, J = 10.5, 8.0, 3.7 Hz, 2H), 2.43 – 2.31 (dddd, J = 13.9, 5.8, 3.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 2.28 – 2.12 (m, 2H), 1.92 – 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.76 – 1.65 (ddt, J = 11.0, 7.7, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 1.63 – 1.56 (m, 2H), 1.55 – 1.11 (m, 16H), 0.96 – 0.81 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 218.50, 136.01, 116.47, 57.74, 39.18, 35.44, 32.67, 32.20, 27.27, 25.92, 24.07, 23.49, 23.39, 22.91, 22.68, 14.13 ; HRMS (ESI+): Exact mass calcd for C17H31O [M+H] +, 251.2369. Found 251.2373.

trans-2-(Acetaldehyde)-3-(n-pentyl)-cyclononanone (33)

To a stirred solution of allylcyclononanone 32 (50 mg, 0.20 mmol) in EtOAc (1 mL) was added NaIO4 (94 mg, 0.44 mmol), OsO4 (2.5 wt% in t-BuOH, 250 μL, 0.02 mmol), and H2O (1 mL). The solution was let stir vigorously overnight before being partitioned between Et2O (3 mL) and brine (3 mL). The organic layer was separated and the aqueous layer extracted with Et2O (3 × 3 mL). The combined organic layers were dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography (10% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound (35 mg, 69%). IR (neat) 2926, 2857, 2720, 1722, 1701, 1465, 1381, 1222, 1121, 1043 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.74 – 9.63 (s, 1H), 3.06 – 2.91 (m, 2H), 2.85 – 2.73 (m, 1H), 2.73 – 2.52 (m, 2H), 1.85 – 1.78 (m, 2H), 1.75 – 1.67 (m, 1H), 1.63 – 1.57 (tt, J = 11.3, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 1.54 – 1.15 (m, 15H), 0.91 – 0.86 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 218.92, 201.18, 50.44, 46.79, 45.80, 40.99, 33.57, 32.11, 27.27, 26.51, 25.67, 25.18, 24.62, 23.57, 22.65, 14.11; HRMS (ESI+): Exact mass calcd for NaC16H28O2 [M+Na+], 275.1982. Found 275.1987.

3-(n-Pentyl)-ortho-cyclononylpyrrole (34)

To a solution of dicarbonyl 33 (20 mg, 0.08 mmol) in dry MeOH (1 mL) was added azeotropically dried NH4OAc (61 mg, 0.8 mmol). The solution was refluxed (65°C) for 30 min before being cooled to RT and diluted with hexanes (3 mL). The solution was directly subject to flash column chromatography (20% EtOAc in hexanes, silica gel) to afford the title compound (15 mg, 80%). IR (neat) 3478, 2283, 2922, 2852, 1458 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.72 – 7.57 (s, 1H), 6.65 – 6.61 (t, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 5.96 – 5.91 (t, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 2.74 – 2.65 (tdd, J = 11.2, 6.1, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 2.65 – 2.60 (m, 2H), 1.90 – 1.79 (m, 1H), 1.64 – 1.23 (m, 17H), 1.08 – 0.93 (dtdd, J = 16.6, 10.8, 4.8, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 0.90 – 0.82 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H).; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 129.62, 122.90, 115.03, 106.15, 37.15, 37.07, 35.92, 32.22, 27.98, 27.75, 27.38, 27.03, 26.89, 23.45, 22.70, 14.22. HRMS (ESI+): Exact mass calcd for C16H28N [M+H+], 234.2216. Found 234.2218.

Pentylcycloheptylprodigiosin·HCl (PCHP, 23)

To a solution of pyrrole 34 (7.6 mg, 0.033 mmol) and bispyrrole aldehyde 820 (12 mg, 0.04 mmol) in MeOH (1 mL) was added dry HCl in MeOH (1 M, 33 μL, 1 eq, freshly prepared from AcCl and MeOH) at 0°C. The solution immediately turns a deep red color, and is allowed to stir for 90 min. A solution of NaOMe (0.066 mL, 25%) was then added, causing the solution to turn dark orange. After 1 hr, the solution was poured into ether (10 mL), extracted in ether (10 × 10 mL) until the aqueous layer was colorless. The combined extracts were washed with brine (10 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. The organic phase was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient: CHCl3 to 1% MeOH/CHCl3, silica gel) to give the product as the hydrochloride salt (14 mg, 96%). IR (neat) 3155, 3131, 3102, 3057, 2924, 2853, 1629, 1604, 1545, 1507,1367, 1232, 1139 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.82 – 12.64 (s, 1H), 12.61 – 12.39 (s, 2H), 7.17 – 7.11 (m, 1H), 6.93 – 6.88 (s, 1H), 6.86 – 6.82 (dt, J = 3.2, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 6.60 – 6.50 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.32 – 6.23 (dt, J = 4.0, 1.9 Hz, 1H), 6.05 – 5.97 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.01 – 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.34 – 3.19 (m, 1H), 2.76 – 2.57 (dddd, J = 19.0, 11.7, 8.7, 3.6 Hz, 2H), 2.15 – 1.97 (dpd, J = 11.9, 6.0, 3.8, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 1.72 – 1.57 (m, 2H), 1.56 – 1.43 (m, 4H), 1.41 – 1.26 (m, 4H), 1.25 – 1.10 (m, 6H), 1.11 – 0.98 (m, 1H), 0.81 – 0.77 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H): 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.78, 152.97, 147.71, 132.42, 126.97, 126.60, 125.71, 122.26, 120.78, 117.03, 116.08, 111.72, 92.85, 58.75, 37.00, 36.88, 35.96, 31.97, 27.64, 27.27, 27.11, 26.89, 26.63, 23.68, 22.65, 14.15; HRMS (TOF EI+): Exact mass calcd for C26H35N3O [M+], 405.2780. Found 405.2798.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis of cyclic prodigiosins

Figure 7.

Relevant EI fragmentation data for the pentyl-homologs of streptorubin B and BCHP, STRB-5C (16) and PCHP (17).

Figure 8.

Relative energies of fragments calculated using Q-Chem (B3LYP-6-31+G* level). Energies for 16, 17, 18, 20 and 21 include the lost neutral radical fragment (i.e., Pr• or Bu•).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Northwestern University (NU), and the National Institutes of Health (1R01GM085322). We thank Prof. Heinz Floss for providing authentic NMR and mass spectra of the pink pigment. We also thank Dr. Amy Sarjeant (NU) and ChemMatCARS (Argonne Advanced Photon Source) for X-ray crystallography of 4•HCl.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds, plus cif files for 2•HCl and 4•HCl. 1H NMR spectra and EI mass spectra of synthetic BCHP (4) and streptorubin B (2), and copies of the corresponding data for the pigment isolated by Floss. DFT data for calculations depicted in Figure 8. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References and Notes

- 1.For general reviews of the chemistry and biology of the prodigiosins, see: Fürstner A. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:3582–3603. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300582.Williamson NR, Fineran PC, Leeper FJ, Salmond GPC. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:887–899. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1531.Williamson NR, Fineran PC, Gristwood T, Chawrai SR, Leeper FJ, Salmond GPC. Future Microbiol. 2007;2:605–618. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.6.605.

- 2.For selected examples, see: Yamamoto D, Kiyozuka Y, Uemura Y, Yamamoto C, Takemoto H, Hirata H, Tanaka K, Hioki K, Tsubura A. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:191–197. doi: 10.1007/s004320050032.Melvin MS, Tomlinson JT, Saluta GR, Kucera GL, Lindquist N, Manderville RA. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6333–6334.Fürstner A, Grabowski J. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:706–709. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010903)2:9<706::AID-CBIC706>3.0.CO;2-J.Gale PA, Light ME, McNally B, Navakhun K, Sliwinski KE, Smith BD. Chem Commun. 2005:3773–3775. doi: 10.1039/b503906a.Sessler JL, Eller LR, Cho W-S, Nicolaou S, Aguilar A, Lee J-T, Lynch VM, Magda DJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:5989–5992. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501740.Seganish JL, Davis JT. Chem Commun. 2005:5781–5783. doi: 10.1039/b511847f.Fürstner A, Radkowski K, Peters H, Seidel G, Wirtz C, Mynott R, Lehmann C. Chem Eur J. 2007;13:1929–1945. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601639.Nguyen M, Marcellus RC, Roulston A, Watson M, Serfass L, Madiraju SRM, Goulet D, Viallet J, Belec L, Billot X, Acoca S, Purisima E, Wiegmans A, Cluse L, Johnstone RW, Beauparlant P, Shore G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19512–19517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709443104.Davis JT, Gale PA, Okunola OA, Prados P, Iglesias-Sanchez JC, Torroba T, Quesada R. Nat Chem. 2009;1:138–144. doi: 10.1038/nchem.178.

- 3.For selected examples of biological activity, see: D’Alessio R, Bargiotti A, Carlini O, Colotta F, Ferrari M, Gnocchi P, Isetta A, Mongelli N, Motta P, Rossi A, Rossi M, Tibolla M, Vanotti E. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2557–2565. doi: 10.1021/jm001003p.Isaka M, Jaturapat A, Kramyu J, Tanticharoen M, Thebtaranonth Y. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1112–1113. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.1112-1113.2002.Ho TF, Ma CJ, Lu CH, Tsai YT, Wei YH, Chang JS, Lai JK, Cheuh PJ, Yeh CT, Tang PC, Chuang JT, Ko JL, Liu FS, Yen HE, Chang CC. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;225:318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.08.007.Papireddy K, Smilkstein M, Kelly JX, Shweta Salem SM, Alhamadsheh M, Haynes SW, Challis GL, Reynolds KAJ. Med Chem. 2011;54:5296–5306. doi: 10.1021/jm200543y. See also, ref. 1.

- 4.O’Brien SM, Claxton DF, Crump M, Faderi S, Kipps T, Keating MJ, Viallet J, Cheson BD. Blood. 2009;113:299–305. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sydor PK, Barry SM, Odulate OM, Barona-Gomez F, Haynes SW, Corre C, Song L, Challis GL. Nat Chem. 2011;3:388–392. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.See ref. 2 for structure-activity relationships related to anion binding and related effects. To the best of our knowledge, the hypothesis we have put forward here proposing a link between conformational restrictions imparted by specific biosynthetic cyclizations and evolutionary advantages thus obtained has not been made before.

- 7.(a) Gerber NN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970;11:809–812. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)97837-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gerber NN. J Antibiot. 1971;24:636–640. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.24.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gerber NN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1970;11:809–812. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)97837-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Laatsch H, Thomson RH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:2701–2704. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kawasaki T, Sakurai F, Hayakawa Y. J Nat Prod. 2008;71:1265–1267. doi: 10.1021/np7007494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Gerber NN. J Antibiot. 1975;28:194–199. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.28.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gerber NN, Stahly DP. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1975;30:807–810. doi: 10.1128/am.30.5.807-810.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber NN, McInnes AG, Smith DG, Walter JA, Wright JLC, Vining LC. Can J Chem. 1978;56:1155–1163.This reassignment was confirmed by NMR studies conducted by Weyland and coworkers in 1991, see: Laatsch H, Kellner M, Weyland HJ. Antibiot. 1991;44:187–191. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.187.

- 10.Tsao S, Rudd B, He X, Chang C, Floss HG. J Antibiot. 1985;38:128–131. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fürstner A, Radkowski K, Peters H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005;44:2777–2781. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeves JT. Org Lett. 2007;9:1879–1881. doi: 10.1021/ol070341i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mo S, Sydor PK, Corre C, Alhamadsheh MM, Stanley AE, Haynes SW, Song L, Reynolds KA, Challis GL. Chem Biol. 2008;15:137–148. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clift MD, Thomson RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14579–14593. doi: 10.1021/ja906122g.Hu DX, Clift MD, Lazarski KE, Thomson RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1799–1804. doi: 10.1021/ja109165f.For selected other prodigiosin syntheses, see: Wasserman HH, Keith DD, Nadelson JJ. Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:1264–1265. doi: 10.1021/ja01033a066.Boger DL, Patel M. J Org Chem. 1988;53:1405–1415.Fürstner A, Krause H. J Org Chem. 1999;64:8281–8286. doi: 10.1021/jo991022a.Fürstner A, Jaroslaw G, Lehmann CW. J Org Chem. 1999;64:8275–8280. doi: 10.1021/jo991021i.Fürstner A, Grabowski J, Lehmann C, Kataoka T, Nagai K. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:60–68. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010105)2:1<60::AID-CBIC60>3.0.CO;2-P.Schultz EE, Sarpong R. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:4696–4699. doi: 10.1021/ja401380d.

- 15.We thank Professor Heinz Floss for a copy of the 1H NMR and EI mass spectrum of the pink pigment, as contained within the following thesis: S.-W. Lee, Biosynthesis on Microbial Metabolites. Part I: Studies on a Red Pigment from Streptomyces. Part II: Tracers Studies on Ansamycin Type Antibiotics, Ph. D. Thesis, Purdue University, West Layfayette, 1983. Copies of the relevant spectra are found in the Supporting Information of this manuscript.

- 16.This condensation is biomimetic in the sense that a related condensation occurs in the biosynthesis of undecylprodigiosin, see: Haynes SW, Sydor PK, Stanley AE, Song L, Challis GL. Chem Commun. 2008:1865–1867. doi: 10.1039/b801677a.

- 17.Attempted direct allylation of the initially formed enolate in the absence of Pd gave reduced yields. Related tandem processes have been reported in the literature. For examples, see: Dijk EW, Panella L, Pinho P, Naasz R, Meetsma A, Minnaard AJ, Feringa BL. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:9687–9693.Alexakis A, Bäckvall JE, Krause N, Pàmies O, Diéguez M. Chem Rev. 2008;108:2796–2823. doi: 10.1021/cr0683515.Jarugumilli GK, Cook SP. Org Lett. 2011;13:1904–1907. doi: 10.1021/ol200059u.

- 18.Pappo R, Allen DS, Jr, Lemieux RU, Johnson WS. J Org Chem. 1956;21:478–479. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kürti L, Czako B. Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Elsevier Inc; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 328–329. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aldrich LN, Dawson ES, Lindsley CW. Org Lett. 2010;12:1048–1051. doi: 10.1021/ol100034p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Positive-ion electrospray tandem mass spectrometry (ES-MS/MS) has been used for structural studies on some prodigiosins, see: Chen K, Rannulu NS, Cai Y, Lane P, Liebl AL, Rees BB, Corre C, Challis GL, Cole RB. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:1856–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.08.002.

- 22.Cif files for 2•HCl and 4•HCl are available in the available online Supporting Information associated with this manuscript.

- 23.STRB-5C (22) was prepared in analogy to our previous synthesis of streptorubin B (2), see ref. 14b. PCHP (23) was prepared in an analogous manner to the synthesis of BCHP (2) outlined herein. See Experimental Section for complete details.

- 24.Shao Y, Molnar LF, Jung Y, Kussmann J, Ochsenfeld C, Brown ST, Gilbert ATB, Slipchenko LV, Levchenko SV, O’Neill DP, DiStasio RA, Jr, Lochan RC, Wang T, Beran GJO, Besley NA, Herbert JM, Yeh Lin C, Van Voorhis T, Hung Chien S, Sodt A, Steele RP, Rassolov VA, Maslen PE, Korambath PP, Adamson RD, Austin B, Baker J, Byrd EFC, Dachsel H, Doerksen RJ, Dreuw A, Dunietz BD, Dutoi AD, Furlani TR, Gwaltney SR, Heyden A, Hirata S, Hsu C-P, Kedziora G, Khalliulin RZ, Klunzinger P, Lee AM, Lee MS, Liang W, Lotan I, Nair N, Peters B, Proynov EI, Pieniazek PA, Min Rhee Y, Ritchie J, Rosta E, David Sherrill C, Simmonett AC, Subotnik JE, Lee Woodcock H, III, Zhang W, Bell AT, Chakraborty AK, Chipman DM, Keil FJ, Warshel A, Hehre WJ, Schaefer HF, III, Kong J, Krylov AI, Gill PMW, Head-Gordon M. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2006;8:3172–3191. doi: 10.1039/b517914a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerdeno AM, Bibb MJ, Challis GL. Chem Biol. 2001;8:817–829. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeno-Tarraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, Harris DE, Quail MA, Kieser H, Harper D, Bateman A, Brown S, Chandra G, Chen CW, Collins M, Cronin A, Fraser A, Goble A, Hidalgo J, Hornsby T, Howarth S, Huang CH, Kieser T, Larke L, Murphy L, Oliver K, O’Neil S, Rabbinowitsch E, Rajandream MA, Rutherford K, Rutter S, Seeger K, Saunders D, Sharp S, Squares R, Squares S, Taylor K, Warren T, Wietzorrek A, Woodward J, Barrell BG, Parkhill J, Hopwood DA. Nature. 2002;417:141–147. doi: 10.1038/417141a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prepared according to Huang Z, Negishi E-i. Org Lett. 2006;8:3675–3678. doi: 10.1021/ol061202o.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.