Abstract

Rituximab combined with chemotherapy has improved the survival of previously untreated patients with follicular lymphoma (FL). Nevertheless, many patients neither want nor can tolerate chemotherapy, leading to interest in biological approaches. Epratuzumab is a humanized anti-CD22 monoclonal antibody with efficacy in relapsed FL. Since both rituximab and epratuzumab have single agent activity in FL, we evaluated the antibody combination as initial treatment of patients with FL.

Patients and Methods

Fifty-nine untreated patients with FL received epratuzumab 360 mg/m2 with rituximab 375 mg/m2 weekly for four induction doses. This combination was continued as extended induction in weeks 12, 20, 28, and 36. Response assessed by CT was correlated with clinical risk factors, FDG-PET findings at week 3, Fcg polymorphisms, immunohistochemical markers, and statin use.

Results

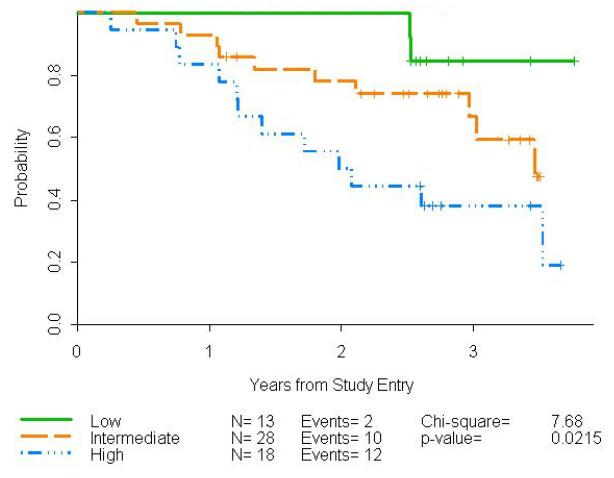

Therapy was well-tolerated with toxicities similar to expected with rituximab monotherapy. Fifty-two (88.2%) evaluable patients responded, including 25 complete responses (CR)(42.4%), and 27 partial responses (45.8%). At 3 years follow-up, 60% of patients remain in remission. Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) risk strongly predicted progression-free survival (p=0.022).

Conclusions

The high response rate and prolonged time to progression observed with this antibody combination are comparable to those observed after standard chemo-immunotherapies and further support the development of biologic, non-chemotherapeutic approaches for these patients.

Introduction

Incorporation of rituximab into chemotherapy regimens for the initial treatment of follicular lymphoma (FL) has improved response rates, and overall survival 1-3. However, not all patients require or tolerate chemoimmunotherapy, and there are acute and long-term toxicities. Thus, studies have evaluated non-cytotoxic strategies for initial treatment of patients with FL. Ghielmini et al published a randomized trial in which patients received 4 weekly doses of rituximab alone or followed by rituximab maintenance every other month for 4 additional doses, demonstrating superior event-free survival and response duration with extended treatment 4. Using this treatment schedule, the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) Lymphoma Committee conducted a series of phase II studies to explore novel biologic combinations with promising agents in combination with rituximab. Rituximab and galiximab achieved a response rate of 72.1% with 47.6% complete responses (CRs) in untreated patients, including a 92% overall response rate (ORR) with 75% CRs in patients with a low Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score 5.

Epratuzumab is a humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against the B-cell specific antigen, CD22, a 135-kDa transmembrane phosphoglycoprotein found on pre-B and mature, normal and lymphoma B cells that acts as a signaling molecule in cellular adhesion, regulation of B-cell homing, and modulation of B-cell activation 6. Although CD22 is internalized into cells following antibody binding, the mechanisms underlying the clinical efficacy of epratuzumab are not entirely clear 7, 8. The highest response rates to epratuzumab in phase I/II studies were observed in patients with FL 9. No dose-limiting toxicity was identified at doses of up to 1000 mg/m2 weekly for four consecutive weeks 9. Epratuzumab plus rituximab has been tested in a weekly x 4 schedule in patients with relapsed FL, with response rates of 54-67% and remissions lasting 13 to 18 months 7, 10. Nevertheless, responses to monoclonal antibody therapy may take weeks to months to occur 11, 12. Herein we report a phase II trial conducted in CALGB evaluating the combination of epratuzumab with rituximab given with extended induction in the treatment of newly diagnosed FL.

This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT00553501.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Objectives

The primary objective of the study was to estimate the ORR within 12 months of study enrollment. ORR is defined as achievement of a complete or partial response as the best-observed response between trial entry and 12 months from enrollment. The Simon minimax design used had a 10% type I error rate at an ORR rate of 70% and 90% power for an ORR of 85%. 13 The experimental therapy was considered sufficiently promising for further investigation if at least 16 of 22 patients had an ORR from the first stage and at least 41 patients had an OR from the cumulative 52 patients after the second stage. Secondary endpoints included time to progression after treatment with epratuzumab and rituximab extended induction therapy, the toxicity profile of the combination, and the correlation of change in FDG uptake early after treatment with response rate and time to progression.

Patient Selection

This multi-institution phase II trial enrolled sixty patients from May, 2008-July, 2009 by 17 CALGB institutions. The trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution, and all patients gave written consent.

Eligibility criteria included age >18 with previously untreated, histologically confirmed FL, grade 1, 2 or 3a with stage III, IV, or bulky (ie, single mass > 7 cm) stage II disease, ECOG performance status 0-2; measureable (e.g. tumor mass > 1.5 cm) disease; no known CNS involvement; and adequate baseline renal and liver function. In addition, the lymphomas were required to be CD20 positive, but CD22 positivity was not required to be documented at study entry. Patients classified as high risk according to the FLIPI were to be considered for another phase III trial, but were allowed on this trial.

Study Treatment

Therapy consisted of rituximab (375 mg/m2/dose) and epratuzumab (360 mg/m2/dose)(Provided by Immunomedics Corp, Morris Plains, N.J.). In week one, rituximab was administered on day 1 and epratuzumab on day 3 to define specific toxicities. Thereafter, the antibodies were given on the same day, with rituximab administered first, followed by epratuzumab, and infusions delivered days 8,15 and 22, and then week 12, 20, 28 and 36 for a total of 8 doses over 9 months. Thirty minutes prior to each rituximab treatment, patient received premedication including diphenhydramine and oral acetaminophen.

Assessments

Patients were restaged during weeks 10, 24 (month 6), and week 40 (month 10), every 4 months for 2 years, then every 6 months until disease progression or for a maximum of 10 years from study entry. Responses and progression were defined according to the revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma 14. CT imaging was used to define response, assessing the sum of the product of the diameters (SPD) of up to six nodes defined on baseline imaging.

Evaluation of interim FDG-PET was exploratory, and the results not included in determining response to treatment for the primary study objective. All baseline and 18-22 day interim PET scans followed a standard protocol. No more than a 10 minute difference in the time from injection to scanning was allowed between baseline and interim PET scans. FDG PET images obtained before treatment were compared to day18-22 PET scans during E + R therapy by a central reviewer blinded to clinical information using visual assessment based on International Harmonization Project criteria 15. A secondary reading was performed using Deauville criteria with the liver uptake as a cut-off for defining positive lesions at all disease sites with focal uptake including the bone marrow and solid organs 16. A semi-quantitative analysis was also performed by determining percent changes in SUVmax between the baseline and interim PET scans in up to 12 lesions measuring above 2.0 cm. ROC curves for SUVmax changes were created to determine a cut off to define a positive and a negative metabolic response.

Pretreatment samples for analyses of V/F 158 FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIa 131 H/R polymorphisms were available for all patients. DNA was extracted using the QIAamp kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Assessment of the of FcγRIIIa and FcγRIIa polymorphisms was performed as previously described 17. All samples were analyzed in duplicate, with identical results.

Tissue microarrays were constructed using duplicate 1mm cores (Beecher Instruments, Sun Prairie, WI) and immunostained using an automated stainer (Benchmark, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) with antibodies to CD10 (56C6, Ventana), CD22 (Sp104, Ventana), CD68 (PGM1, Dako, Carpinteria CA), BCL6 (PGB6p, DAKO), MUM1(MUM1p, DAKO), FOXP1 (JC12, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), FOXP3(236A/E7, Novus, Littleton, CO), BCL2 (124, CellMarque, Rocklin, CA), PD1(NAT, Abcam), and Ki67(30-9, Ventana). Stains (except Ki67 and CD22) were evaluated independently by 2 experienced hematopathologists blinded to clinical outcome. Recorded scores were the average of the 2 estimates. In cases where estimates were >20% different, a third pathologist reviewed the stain to resolve the discrepancy and render a score. CD10 and BCL6 was scored as negative (0% tumor cells), weak (1-30% tumor cells), or strong (>30% tumor cells) and MUM1 was scored positive with a cutoff of >20% in tumor cells 18, 19. BCL2 was scored positive with a cutoff of 30% tumor cells.

The architectural pattern of FOXP3+ T-cells is an independent predictor of survival in patients with follicular lymphoma, and FOXP3 was evaluated for follicular pattern defined by accentuation of FOXP3+ T-cells within or around follicles 20. CD68 was scored by counting the number of positive cells (macrophages) in intra- and inter-follicular cells/hpf (average of 3 fields) 21. FOXP1 in tumor cells was scored in 10% increments. PD1 was scored in follicles as 0 (<2%), 1+ (2-10%); and 3+ (>10%). Nuclear Ki67 staining was scored by image analysis (ImagePro 5.0, MediCybernetics, Rockville, MD). CD22 expresion in lymphoma cells was scored to nearest 10% by one pathologist (EDH).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

One patient who was determined to have stage 1 disease was excluded from all analyses. Baseline characteristics of the remaining 59 treated patients are presented in Table 1: 96.6% of patients had stage III/IV lymphoma, and 30.5% had a high FLIPI score. Three patients received steroids for supportive care in the first two weeks and were excluded from the evaluation of PET data.

Table 1.

Summary of Base-line Patient Characteristics (n=59)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (Range) | 54 (32-90) |

| CD22 Expression | |

| Median (Range) | 50% (10-100%) |

| Missing | 17 |

| n (%) | |

| Age | |

| ≤ 60 | 44 (74.6) |

| > 60 | 15 (25.4) |

| Race | |

| White | 54 (94.7%) |

| Black | 2 (3.5%) |

| Asian | 1 (1.8%) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Male | 24 (40.7) |

| Stage | |

| II | 2 (3.4) |

| III | 19 (32.2) |

| IV | 38 (64.4) |

| B Symptoms | 4 (7.0) |

| Missing | 2 |

| WHO Classification | |

| Grade 1 | 32 (56.1) |

| Grade 2 | 22 (38.6) |

| Grade 3a | 3 (5.3) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Performance Status | |

| 0 | 37 (62.7) |

| 1 | 22 (37.3) |

| FLIPI | |

| Low | 13 (22.0) |

| Intermediate | 28 (47.5) |

| High | 18 (30.5) |

| Statin Use | 16 (27.6) |

| Missing | 1 |

| FcgR2A | |

| Arg/His | 30 (54.5%) |

| Arg | 14 (25.5%) |

| His | 11 (20.0%) |

| Missing | 4 |

| FcgR3A | |

| V/F (n=16) | 16 (29.1%) |

| V (n=10) | 10 (18.2%) |

| F (n=29) | 29 (52.7%) |

| Missing | 4 |

| IHP-Based PET | |

| Pos | 42 (87.5%) |

| Neg | 6 (12.5%) |

| Missing | 11 |

| Liver-Based PET | |

| Pos | 37 (77.1%) |

| Neg | 11 (22.9%) |

| Missing | 11 |

Responses

With all 59 eligible patients having completed protocol therapy, the ORR was 88.2%; with 25 achieving a CR (42.4%) and 27 a PR (45.8%), and 6 (10.2%) had stable disease. One patient (1.7%) completed all courses of treatment but was inevaluable for response because of death due to MRSA before the time of response assessment. Accounting for the two-stage design, the uniformly minimum variance unbiased estimate 22 of the ORR is 88.1%, its 80% confidence interval 23 is (80.9%,93.3%), and the p-value 24 is 0.0009, concluding that the ORR of the study is significantly higher than 70%

All 25 patients with CR completed all treatment, as did 25 (92.6%) of 27 PRs. Four of 6 non-responders completed all therapy, one died during induction, and one was taken off due to progression at month 5.

At the time of this analysis, 24 (40.7%) of the 59 patients have reached a study endpoint, including three deaths and 21 lymphoma progressions. Progression has been observed in 4 of the 25 CRs, 13 of the 30 PRs, and 4 of 6 patients with stable disease.

There have been 5 deaths to date, including one endocarditis, one MRSA septic shock, one patient with stable disease who progressed but died from necrotizing bronchopneumonia, one patient who progressed after achieving a PR, and one from cardio-pulmonary collapse/peritonitis.

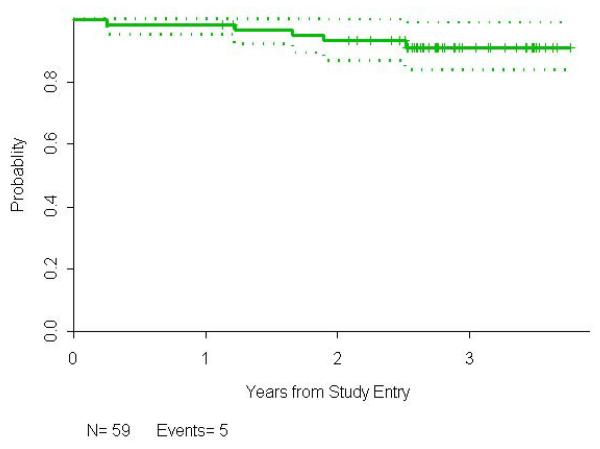

The median follow-up time for all patients is 2.8 years (0.3-3.7), and 2.7 years (1.1-3.8) for the 35 patients who have neither progressed nor died. The estimated median PFS is 3.5 (2.6, 4.4) years, with an estimated probability of PFS of 0.92 (95% confidence interval, 0.81,0.96) at 1 year, 0.74 (0.61,0.84) at 2 years, and 0.60 (0.44,0.73) at 3 years. The probability of survival at 3 years is 0.91 (0.80,0.96).

Correlates of Clinical Outcome

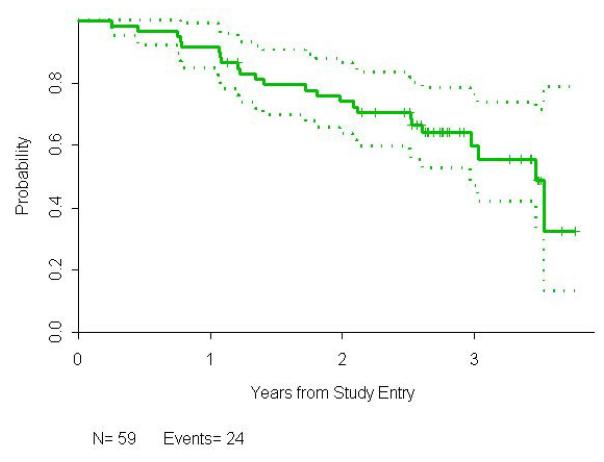

PFS was associated with FLIPI risk, p=0.022, (Fig 1) and 84% of patients who achieved a CR remained disease-free at 3 years. Forty-eight percent of PRs remained in remission and 17% with stable disease had neither progressed nor died by 3 years.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival for all 59 previously untreated FL patients who received rituximab and epratuzumab.

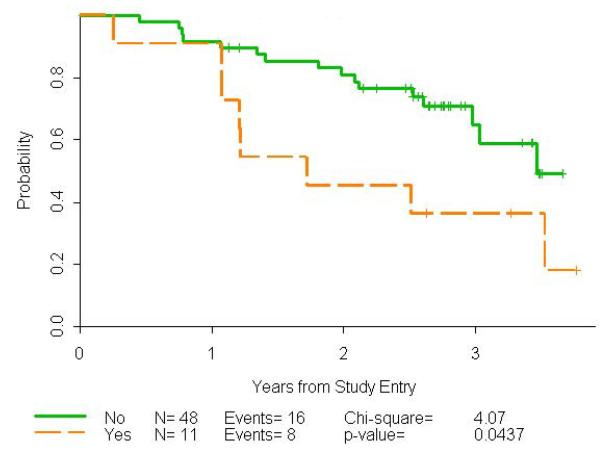

There were 11/59 (18.6%) patients with bulky disease as defined as any single nodal mass > 7 cm. The CR rate in the patients with bulky disease was 1/11 (9.1%) compared to 24/48 (50.0%) in those without bulky disease, p=0.017, Fisher’s Exact Test. Progression-free survival was worse in those with bulky disease, HR=2.40, p=0.044, log rank test (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Progression-free survival by bulky disease using a cut-off of 7 cm.

The median time to CR was 9.2 months with a range of 2.2-24.5 months. Statin use did not impact response or PFS in contrast to prior reports 25.

Neither the visual evaluation using IHP or Deauville criteria nor the percent change in SUVmax between baseline and day 18-22 of treatment predicted CR rate, overall response rate, or PFS.

Toxicity/AEs/Second malignancy

The combination of rituximab and epratuzumab was extremely well-tolerated. Infusional reactions similar to those commonly observed with rituximab alone occurred, with urticaria (2 (3%)), hypersensitivity (3 (5%) grade 2), or hypotensive events (3 (5%)). Severe adverse events included one myocardial infarction, 2 episodes of severe fatigue (3%), 2 episodes of severe nausea and diarrhea (3%), 2 reports of severe muscle weakness (3%), 3 of severe pain (5%), 5 (8%) of moderate pain, and 1 each (2%) of dyspepsia and emesis.

One patient was taken off treatment due to disease progression after month 5, another developed line sepsis during week three of induction, and died with endocarditis and renal failure two months later. Two patients were taken off study due to adverse events, 1 during induction (grade 4 thrombosis and myocardial infarction) and 1 following month 5 (grade 3 dyspnea, hypoxia, not otherwise specified).

Neutropenic episodes occurred infrequently (3 (5%) grade 2 and 1 (2%) grade 3), though moderate fatigue was reported by 10 (17%) patients. Other adverse events were grade 2 or less and occurred in less than 3% of patients. Two secondary malignancies have been reported; one kidney cancer diagnosed 18 months after starting therapy and one colon cancer 18 months after starting therapy.

Biomarkers

There were no significant associations (P>0.05) between aberrant phenotype (CD10-, BCL6-, FOXP1+, or MUM1+) FL and CR, overall response or EFS. (Table 2) Likewise, numbers of CD68+ lymphoma associated macrophages, FOXP3 pattern, number of PD1+ T-cell, BCL-2 expression, and Ki67 proliferative fraction showed no significant association these clinical outcome parameters. Finally, Fcγ polymorphism studies and CD22 expression level showed no correlation with CR, RR, or EFS. Of note, patients lacking of BCL6 expression appeared to have a lower response rate (13/17, 76.5%) than patients with BCL6 expression (25/27, 92.5%) with a shorter PFS and hazard ration of 0.53 for those with BCL6 expression. While not significant, the trend (P=0.146) is worthy of further investigation.

Table 2.

Biomarker Analyses

| Marker | Number | CR Rate | p-value | OR Rate | p-value | PFS Rate | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUM1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.336 | ||||

| Neg | 35 (83.3%) |

15 (42.9%) |

30 (85.7%) |

19 (54.3%) |

|||

| Pos | 7 (16.7%) | 3 (42.9%) | 6 (85.7%) | 2 (28.6%) | |||

| Missing | 3 | ||||||

| BCL 6 | 0.734 | 0.186 | 0.146 | ||||

| Neg | 17 (38.6%) |

6 (35.3%) | 13 (76.5%) |

10 (58.8%) |

|||

| Pos | 27 (61.4%) |

12 (44.4%) |

25 (92.6%) |

12 (44.4%) |

|||

| Missing | 1 | ||||||

| CD 10 | 0.738 | 0.154 | 0.787 | ||||

| Neg | 11 (25.0%) |

5 (45.4%) | 8 (72.7%) | 6 (54.6%) | |||

| Pos | 33 (75.0%) |

13 (35.4%) |

30 (90.9%) |

16 (48.5%) |

|||

| Missing | 1 | ||||||

| FOX P3 | 0.745 | 0.647 | 0.822 | ||||

| Neg | 15 (34.9%) |

5 (33.3%) | 12 (80.0%) |

7 (46.7%) | |||

| Pos | 28 (65.1%) |

12 (42.9%) |

25 (89.3%) |

15 (53.6%) |

|||

| Missing | 2 | ||||||

| BCL 2 | 0.407 | 1.000 | 0.486 | ||||

| Neg | 7 (16.3%) | 4 (57.1%) | 6 (85.7%) | 2 (28.6%) | |||

| Pos | 36 (83.7%) |

13 (36.1%) |

31 (86.1%) |

20 (55.6%) |

|||

| Missing | 2 | ||||||

| FOX P1 | 1.000 | 0.646 | 0.397 | ||||

| Neg | 26 (65.0%) |

11 (42.3%) |

23 (88.5%) |

11 (42.3%) |

|||

| Pos | 14 (35.0%) |

6 (42.9%) | 11 (78.6%) |

8 (57.1%) | |||

| Missing | 5 | ||||||

| PD1 | 0.583 | 0.336 | 0.872 | ||||

| 0+ | 2 ( 5.1%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | |||

| 1+ | 7 (18.0%) | 2 (28.6%) | 6 (85.7%) | 3 (42.9%) | |||

| 2+ | 13 (76.9%) |

13 (43.3%) |

26 (86.7%) |

16 (53.3%) |

|||

| Missing | 6 |

DISCUSSION

Our study confirms that immunotherapy without cytotoxic therapy can achieve durable remissions in untreated FL. Martinelli 26 reported that 45% of responding, previously untreated patients with follicular lymphoma given rituximab single antibody therapy remained progression-free at 8 years. The challenge has been to identify which patients will respond with very durable remissions, and to find agents that will amplify the activity of rituximab without adding toxicity.

In our study, epratuzumab plus rituximab yielded a response rate of 88.2%, and an overall three year PFS of 60%. The lengthy PFS observed in low and intermediate FLIPI patients after treatment with this doublet compares favorably with those reported for both chemotherapy and non-chemotherapy based regimens 2, 5, 26-28, and suggests that epratuzumab extends the efficacy of rituximab in treatment of FL.

The durable remissions observed in this study are at least comparable to those reported for other FL regimens. At three years, 60% of patients in our cohort remain in remission, compared with 64% for R-bendamustine 28, 47-57% for R-CHOP 27, 28, 50% for R-CVP 2, 48% for rituximab + galiximab 5 and 39 to 51% for patients treated with rituximab alone 26. Of those patients with low and intermediate 85% and 67%, respectively, were still in remission at 3 years. These results for lower risk cohorts are better than those reported for similar patients after R-CHOP 27. However patients with high FLIPI scores on our study did not remain in remission after R+E as long as has been reported after chemoimmunotherapy such as R-CHOP 27.

Epratuzumab has in vitro and clinical characteristics that support its potential efficacy in follicular lymphoma. CD22, is expressed on almost all B cells 29although expression may be aberrant in FL 30. However, we noted no difference in response based on CD22 assessment. Epratuzumab demonstrates both cytotoxic activity against lymphoma in vitro and immunomodulatory activity 6, 31, 32 with the potential to improve and lengthen responses after rituximab. Unexpectedly prolonged responses observed in a subset of patients with relapsed FL treated with R+E in phase II trials 10 supported this trial in untreated patients.

Whereas the overall estimated 3 year PFS for our previously untreated cohort was 60%, it was 85% for those with low FLIPI, 67% for those with intermediate risk, and 38% for those with high FLIPI scores. Although our study was intended for lower risk FL, enrollment included 48% intermediate and 30% high risk patients. This patient population reflects the interest of patients and clinicians in chemotherapy-free treatment approaches in this setting. Eighty-four percent of patients who achieved CR remained disease-free at 3 years; 48% of those who achieved a PR remained in remission, with 16% of those with stable disease not yet progressed.

The response rate observed with this doublet is similar to that described by Ghielmini for previously untreated patients given rituximab at the same dose and schedule (90%)4, and that observed by our group for the combination of galiximab plus rituximab delivered in the same extended induction schedule (72.1%) 5. Patient selection likely influences, in part, the observed response rates.

An important aim of our study was to evaluate patient and tumor characteristics associated with response or response duration after epratuzumab and rituximab therapy. FLIPI clinical characteristics in our patients were associated with disease-free survival after treatment; no other patient characteristics were identified. Observed responses to R+E were not different across the FLIPI categories. Early response measured by change in FDG uptake did not identify those likely to enjoy a long DFS. With a median follow up of 2.7 years, we were unable to confirm an association with biomarkers and response or survival as in other trials 33-38, although it is possible that with larger patient numbers and longer follow-up, individual markers might identify such patients.

There is a paucity of prospective PET data for follicular lymphoma acquired with standardized imaging protocols and interpreted with uniform interpretation criteria. Moreover, the majority of quantitative PET analyses were based on retrospective data evaluations 39, 40. Most studies investigating the role of PET posttreatment have demonstrated strong correlations with patient outcome 39-41

There is no firm evidence that FDG PET plays a role in interim response evaluation during induction therapy in FL patients. This present study is the first to assess a potential predictive role for interim PET scan performed very early during the course of induction therapy. Our results did not support the use of an interim PET as a surrogate for response or survival for advanced stage FL patients. FDG uptake at 3 weeks after R + E likely reflects both remaining lymphoma and an inflammatory reaction. Other studies have failed to show a correlation between mid-treatment PET during chemo-immunotherapy and patient outcome 40.

Rituximab plus epratuzumab was extremely well tolerated, with DFS at 3 years similar to that observed after treatment with chemoimmunotherapy, confirming that immunotherapy may have an important role in the initial treatment of FL, particularly among patients with FLIP low-risk disease. Longer follow-up will clarify the durability of responses, the patient and tumor characteristics predictive of extended disease free survival, and analysis of long term toxicities associated with conventional chemoimmunotherapy regimens.

Figure 2.

Progression-free survival by FLIPI score for all 59 previously untreated FL patients who received rituximab and epratuzumab.

Figure 3.

Overall survival for all 59 FL patients treated with rituximab and epratuzumab.

Table 3.

Correlation between biomarkers and endpoints with rituximab-epratuzumab therapy

| Endpoint | Marker | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD68 Intra | CD68 Inter | Ki67 % Pos | ||||

| n (median) | p-value | n (median) | p-value | n (median) | p-value | |

| CR | 0.792 | 0.201 | 0.271 | |||

| No | 19 (7.8) | 23 (13.0) | 26 (10.9) | |||

| Yes | 16 (5.6) | 17 (21.0) | 19 (15.3) | |||

| OR | 0.411 | 0.111 | 0.173 | |||

| No | 6 (6.0) | 6 (10.6) | 6 (10.8) | |||

| Yes | 29 (7.0) | 34 (21.5) | 39 (13.5) | |||

| PFS | 0.805 | 0.717 | 1.000 | |||

| No | 19 (5.8) | 21 (21.0) | 23 (11.5) | |||

| Yes | 16 (7.6) | 19 (14.0) | 22 (14.1) | |||

| Cox Model HR |

0.99 | 0.702 | 1.04 | 0.242 | 0.99 | 0.966 |

| Overall | ||||||

| n | 35 | 40 | 45 | |||

| Median/range | 7.0 (2.0,33.0) |

15.1 (1.0, 65.5) |

12.6 (1.4,32.1) |

|||

Acknowledgments

The research for CALGB 50701 (Alliance) was supported, in part, by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA31946) to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology and the Alliance Statistics and Data Center (CA33601), and institutional grants (CA45418), (CA32291), (CA77597), (CA45389), (CA45808), (CA77658), (CA60138), (CA74811), (CA47642), (CA47559), (CA77406), (CA03927), (CA26806), (CA77440), (CA07968)

Footnotes

Drs. Cheson and Leonard have been paid consultants to Genentech, Inc.

Bibliography

- 1.Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cylophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2005;106:3725–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcus RE, Imrie K, Solal-Celigny P, et al. A phase III study of rituximab plus CVP versus CVP alone in patients with previously untreated advanced follicular lymphoma: updated results with 53 months’ median follow-up and analysis of outcomes according to baseline prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herold M, Haas A, Srock S, et al. Rituximab added to first-line mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisolone chemotherapy followed by interferon maintenance prolongs survival in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma: an East German Study Group Hematology and Oncology study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1986–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghielmini M, Schmitz SF, Cogliatti SB, et al. Prolonged treatment with rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma significantly increases event-free survival and response duration compared with weekly x 4 schedule. Blood. 2004;103:4416–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czuczman MS, Leonard JP, Jung S, et al. Phase II trial of galiximab (anti-CD80 monoclonal antibody) plus rituximab (CALGB 50402): Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score is predictive of upfront immunotherapy responsiveness. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2356–10. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daridon C, Blassfeld D, Reiter K, et al. Epratuzumab targeting of CD22 affects adhesion molecule expression and migration of B-cells in systemic lupus erythematosis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R204. doi: 10.1186/ar3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss SJ, Morschhauser F, Rech J, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of immunotherapy with the humanized anti-CD22 antibody, epratuzumab, in combination with rituximab, in refractory or recurrent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3880–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Micallef IN, Maurer MJ, Wiseman GA, et al. Epratuzumab with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy in patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4053–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonard JP, Coleman M, Ketas JC, et al. Phase I/II trial of epratuzumab (humanized anti-CD22 antibody) in indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3051–59. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonard JP, Schuster SJ, Emmanouilides C, et al. Durable complete responses from therapy with combined epratuzumab and rituximab: final results from an international multicenter, phase 2 study in recurrent, indolent, non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer. 2008;113:2714–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Czuczman MS, Thall A, Witzig TE, et al. Phase I/II study of galiximab, an anti-CD80 antibody, for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4390–98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonard JP, Friedberg JW, Younes A, et al. A phase I/II study of galiximab (anti-CD80) monoclonal antibody in combination with rituximab for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1216–23. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon R. Optimal two-stage designs for phase II clinical trials. Controlled Clin Trials. 1989;10:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an International Workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:579–86. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meignan M, Gallamini A, Haioun C. Report on the first International Workshop on Interim-PET-scan in lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:1257–60. doi: 10.1080/10428190903040048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood. 2002;99:754–58. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naresh KN. MUM1 expression dichotomises follicular lymphoma into predominately MUM1-negative low-grade and MUM1-positive high-grade subtypes. Haematologica. 2007;92:267–68. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweetenham JW, Goldman BH, LeBlanc ML, et al. Prognostic value of regulatory T cells, lymphoma-associated macrophages, and MUM-1 expression in follicular lymphoma treated before and after the introduction of monoclonal antibody therapy: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1196–202. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farinha P, Campo E, Banham AH, et al. The architecural pattern of FOXP3+ T cells is an important predictor of survival in patients with follicular lymphoma. Med Pathol. 2006;19:224A. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley T, Nech R, Absi A, Jin T, Pohlman B, Hsi E. Biologic predictors in follicular lymphoma: importance of markers of immune response. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:2403–11. doi: 10.1080/10428190701665954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung SH, Kim KM. On the estimation of the binomial probability in multistage clinical trials. Stat Med. 2004;23:881–96. doi: 10.1002/sim.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennison C, Turnbull BW. Confidence intervals for a binomial parameter following a multistage test with application to MIL-STD 105D and medical trials. Technometrics. 1983;25:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung SH, Owzar KM, George SL, Lee TY. P-value calculation for multistage phase II cancer clinical trials (with discussion) J Biopharmaceutical Stat. 2006;16(756-783) doi: 10.1080/10543400600825645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nowakowski GS, Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, et al. Statin use and prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:412–17. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinelli G, Schmitz SF, Utiger U, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with follicular lymphoma receiving single-agent rituximab at two differnet schedules in trial SAKK 35/98. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4480–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe T, Tobinai K, Shibata T, et al. Phase II/III study of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-CHOP-21) versus two-week R-CHOP (R-CHOP-14) for untreated indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) 0203 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.8508. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rummel M, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab (B-R) versus CHOP plus rituximab (CHOP-R) as first-line treatment in patients with indolent and mantle cell lymphomas (MCL): Updated results from the StiL NHL1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 abstract 3. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deneys V, Mazzon AM, Marques JL, Benoit H, De Bruyere M. Reference values for periphearl blood B-lymphocyte subpopulations: a basis for multiparametric immunophenotyping of abnormal lymphocytes. J Immunological Methods. 2001;253(1-2):23–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J, Fan G, Zhong Y, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of aberrant CD22 expression in differentiating neoplastic cells of B-cell chronic lymphoproliferative disorders from admixed benign B cells in four-color multiparameter flow cytometry. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:828–32. doi: 10.1309/KPXN-VR7X-4AME-NBBE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carnahan J, Wang P, Kendall R, et al. Epratuzumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting CD22: characterization of in vitro properties. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(10 pt 2):3982S–90S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carnahan J, Stein R, Qu Z, et al. Epratuzumab, a CD22-targeting recombinant humanized antibody with a different mode of action from rituximab. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:1331–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dave SS, Wright G, Tan B, et al. Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. New Engl J Med. 2004;351:2159–69. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canioni D, Salles G, Mounier N, et al. High numbers of tumor-associated macrophages have an advers prognostic value that can be circumvented by rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma enrolled onto the GELA-GOELAMS FL-2000 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:440–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.8298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carreras J, Lopez-Guillermo A, Fox BC, et al. High numbers of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3-positive regulatory cells are associated with improved overall survival in follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2006;108:2957–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farinha P, Masoudi H, Skinnider BF, et al. Analysis of multiple biomarkers shows that lymphoma-associated macrophages (LAM) content is an independent predictor of survival in follicular lymphoma (FL) Blood. 2005;106:2169–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Relander T, Johnson NA, Farinha P, Connors JM, Sehn LH, Gascoyne RD. Prognostic factors in follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2902–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Persky DO, Dornan D, Goldman BH, et al. Fc gamma receptor 3a genotype predicts ovearll survival in follicular lymphoma patients treated on SWOG trials with combined monoclonal antibody plus chemotherapy but not chemotherapy alone. Haematologica. 2012;97:937–42. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.050419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trotman J, Fournier M, Lamy T, et al. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) after induction therapy is highly predictive of patient outcome in follicular lymphoma: analysis of PET-CT in a subset of PRIMA trial participants. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(3194-3200) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bishu S, Quigley JM, Bishu SR, et al. Predictive value and diagnostic accuracy of F-18-fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography in treated grade 1 and follicular lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1548–55. doi: 10.1080/10428190701422059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zinzani PL, Musuraca G, Alinari L, et al. Predictive role of positron emission tomography in the outcome of patients with follicular lymphoma. Clin Lymp, Leuk, Myeloma. 2007;7:291–95. doi: 10.3816/CLM.2007.n.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]