Abstract

Membrane-lined channels called plasmodesmata (PD) connect the cytoplasts of adjacent plant cells across the cell wall, permitting intercellular movement of small molecules, proteins, and RNA. Recent genetic screens for mutants with altered PD transport identified genes suggesting that chloroplasts play crucial roles in coordinating PD transport. Complementing this discovery, studies manipulating expression of PD-localized proteins imply that changes in PD transport strongly impact chloroplast biology. Ongoing efforts to find genes that control root and stomatal development reveal the critical role of PD in enforcing tissue patterning, and newly discovered PD-localized proteins show that PD influence development, intracellular signaling, and defense against pathogens. Together, these studies demonstrate that PD function and formation are tightly integrated with plant physiology.

INTRODUCTION

In multicellular organisms, cells coordinate development, share resources, and communicate physiological and environmental changes. In plants, small membrane-lined channels called plasmodesmata (PD) connect the cytoplasts of adjacent cells across the cell wall, permitting intercellular transport and communication. PD are bound by plasma membrane at their outer limits and contain a central strand of tightly compressed endoplasmic reticulum (the "desmotubule") that almost completely lacks luminal space. Molecules predominantly traffic from cell to cell through the cytosolic sleeve in between the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 1). PD allow exchange of small molecules, such as ions, sugars, and phytohormones, as well as larger molecules, including proteins, RNA, and viruses. Most PD transport occurs via diffusion, but some proteins—viral movement proteins, for example—are targeted to PD and transport more rapidly by mechanisms that remain poorly understood but are currently under investigation [1].

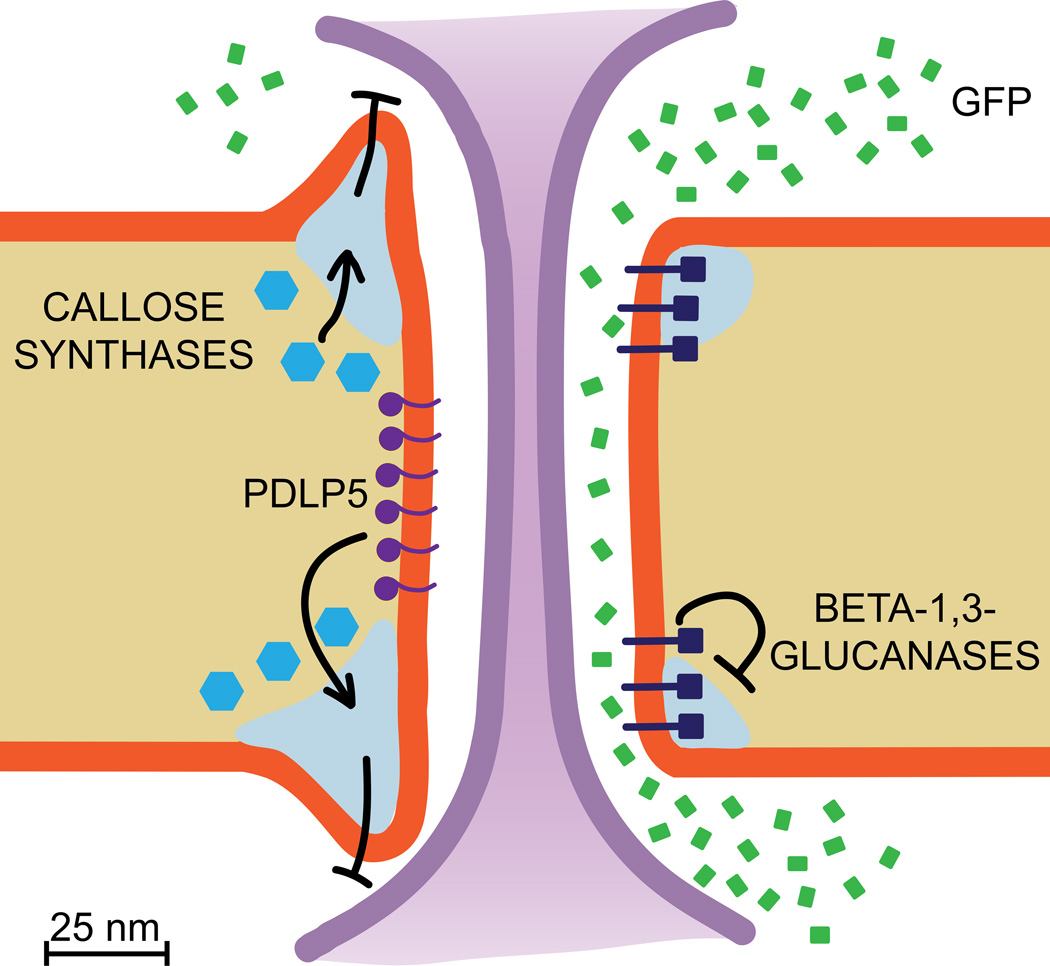

Figure 1.

Scaled cartoon model of a plasmodesma, following Tilsner et al. [55]. Plasmodesmata are plasma membrane-lined channels that cross the cell wall, containing cytosol and a central, tightly compressed strand of endoplasmic reticulum called the desmotubule (purple). The cytosol is continuous between adjacent cells, allowing small and large molecules to move from one cell to the next. Here, GFP (green) is moving via diffusion through PD. Callose deposition bordering PD (light blue areas) negatively regulates PD transport, and is mediated by callose synthases (blue hexagons, left). Degradation of callose bordering PD positively regulates PD transport, and is mediated by β-1,3-glucanases (dark blue hexagons with membrane-spanning tails, right). Some PD proteins affect PD transport through unclear mechanisms, such as PDLP5 (purple circles with membrane-spanning tails, left), which here is shown inhibiting GFP transport, possibly by promoting local callose synthesis.

PD research is challenging for several reasons. First, PD are very small (~30–50nm in diameter) and difficult to isolate from other membranes, which has long prevented direct analysis of PD components [2]. Second, PD are essential to plant survival: all land plants have PD, and no mutant lacking PD has ever been isolated [3,4]. Third, PD function is extremely sensitive to manipulation (such as mechanical stress), which complicates efforts to directly assay PD transport [5]. For many years, the PD size exclusion limit (SEL) was believed to be ~1 kDa; we now know that the technique previously used to measure PD transport (microinjection of small fluorescent tracers) rapidly triggers PD closure [5], and that the actual SEL is typically at least 27 kDa (the size of GFP), and can often be larger [6].

Despite these difficulties, PD research has made significant progress. Here, we describe (i) insights into the regulation of PD function and formation gained from genetic approaches, (ii) new discoveries pertaining to PD transport of transcription factors, and (iii) our expanding knowledge of PD protein components. These studies support a common theme: PD function and formation are tightly integrated with intracellular signaling pathways and plant physiology.

Regulation of PD Function and Formation: Genetic Insights

In the last decade, three mutant screens were conducted to identify genes regulating PD transport. The first looked for altered movement of fluorescent tracers in embryo-defective mutants, reasoning that any mutant with strong effects on PD transport would exhibit severely disrupted development [3]. From this screen, three mutants have been characterized so far: increased size exclusion limit 1 and 2 (ise1 and ise2), which have increased PD transport, and decreased size exclusion limit 1 (dse1), which has decreased PD transport [3,7–10]. Two other screens searched for mutants with decreased protein movement (i) from the phloem to surrounding tissues or (ii) from the mesophyll to the epidermis. These efforts led to the characterization of two PD mutants: gfp arrested trafficking 1 (gat1) and chaperonin containing TCP1 8 (cct8) [11–13]. Unexpectedly, none of the genes recovered from these screens encode proteins that localize to PD. ISE1 and ISE2 are RNA helicases that localize to mitochondria and plastids, respectively; DSE1 is a WD40-repeat containing protein found in the cytoplasm and nucleus; GAT1 is a plastid-localized thioredoxin; and CCT8 is a cytoplasmic chaperonin subunit.

Chloroplasts Regulate PD… and PD Regulate Chloroplasts!

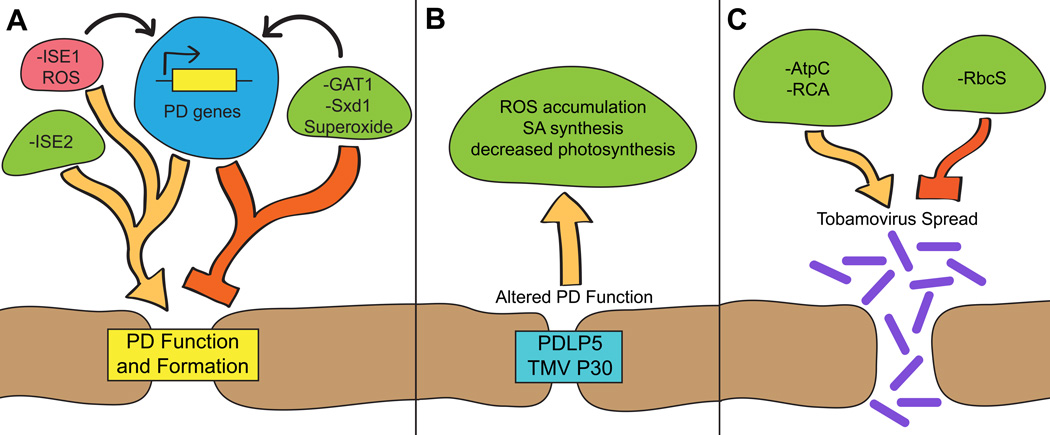

Intriguingly, three of these five mutants contribute to a single narrative: PD function and formation are strongly regulated by intracellular signals originating from mitochondria and plastids. Beyond dramatically increasing PD transport and formation [14], loss of either ISE1 or ISE2 affects the expression of ~3,000 genes; genes that encode chloroplast proteins are remarkably overrepresented in both transcriptomes [9]. PD transport is severely reduced in mutants lacking the plastid thioredoxin GAT1, which overproduce hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a known upstream signal impacting intracellular processes and nuclear gene expression [11]. Together, these results demonstrate that there must be extensive signaling among organelles, the nucleus, and PD to coordinate intercellular transport [9]. Physiological studies reinforced this model by showing that changes in the redox states of mitochondria or chloroplasts serve as upstream signals to rapidly alter PD transport [15]. All of these findings have been extensively discussed [16], and are summarized in Figure 2A; here, we focus on studies that lend further support to this model.

Figure 2.

(A) Plasmodesmata function and formation are coordinated by changes in chloroplast (green) and mitochondrial (red) function. These changes alter expression of nuclear genes (blue) through organelle retrograde signaling pathways (black arrows). Loss of organelle RNA helicases (ISE1 or ISE2) causes dramatic changes in nuclear gene expression and increases PD transport and biogenesis. ROS produced specifically in the mitochondria also positively regulates PD function. On the other hand, superoxide formation in the chloroplast or loss of either GAT1 or Sxd1 [56,57] (which also leads to oxidation of the chloroplast redox state) negatively regulate PD function. (B) PD function regulates chloroplast physiology: PDLP5 or P30 expression cause increased ROS formation, SA biosynthesis, and decreased photosynthesis. (C) Various chloroplast proteins also impact tobamoviral spread, possibly through effects on PD function.

Research on viral pathogenesis often provides insights into PD function, since viruses pirate PD for their spread through plant tissues [1,17]. In a stunning convergence of discoveries across different fields, several studies revealed that chloroplast proteins can inhibit or enhance the spread of tobamoviruses, potentially by modifying PD function (Fig. 2C). Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) spreads more rapidly in tobacco plants that have silenced expression of the plastid-localized ATP synthase gamma subunit (AtpC) or RuBisCO activase (RCA) [18]. On the other hand, silencing the RuBisCO small subunit (RbcS) delays the spread of Tomato mosaic tobamovirus (ToMV) [19]. These observed changes in pathogenesis could be related to several aspects of viral spread, such as altered viral replication. In light of the mounting evidence that chloroplasts coordinate PD transport, and that loss of ISE1 or ISE2 causes increased PD transport of tobamovirus movement proteins in particular [14], future studies should also consider that disrupting chloroplast function can have downstream effects on PD transport, and that these changes in PD transport could be partially responsible for the observed abnormal viral spread.

Studies focused on PD proteins have further emphasized the relationship between chloroplasts and PD. Not only do chloroplasts regulate PD—changes in PD transport in turn disrupt chloroplast function (Fig. 2B). First, overexpression of PDLP5 (a protein specifically localized at PD; see below), which decreases PD transport [20, 21], leads to chlorosis and overaccumulation of salicylic acid (SA), a phytohormone synthesized in plastids [22]. Second, transgenic expression of the TMV movement protein (P30), which predominantly localizes to PD and promotes viral transport, leads to increased H2O2 accumulation, overaccumulation of SA, and transcriptional induction of SA-response and chloroplast ROS-scavenging genes [23]. Older studies showed that transgenic P30 expression also decreases the rate of photosynthetic carbon assimilation [24]. In concert, these discoveries imply that chloroplasts are sensitive to alterations in PD function.

PD Regulate Plant Development: Stomata Formation

Multiple studies over the past few years have underscored the crucial involvement of PD in plant development. By governing movement of biological macromolecules that determine cell fate (such as transcription factors, see below), PD play a prominent role in tissue formation and patterning. Indeed, several screens for mutants defective in developmental processes have found weak mutant alleles of genes that affect PD transport.

In the plant epidermis, stomatal guard cell differentiation is initiated by a transcription factor, SPEECHLESS (SPCH) [25]. Genetic screens for defective stomatal complex formation found two mutants, chorus and kobito1, both with increased PD movement that allows SPCH to traffic out of a differentiating guard cell and initiate spurious guard cell formation [26,27].

chorus is a weak recessive allele of GLUCAN SYNTHASE-LIKE 8 (GSL8), a gene that encodes a putative callose synthase [26,28,29]. Callose is a cell wall polysaccharide that restricts intercellular transport when deposited just outside PD (Fig. 1), and is also deposited at the cell plate during cytokinesis [29]. Plants with a strong loss-of-function allele of gsl8 are defective in cell division and have an extremely disorganized epidermis, including aggregation of guard cells, possibly due to incomplete cytokinesis or due to changes in PD transport of developmental signals [28]. In chorus mutants, which do not show strong defects in cell division, callose does not accumulate to wild-type levels at PD, and accordingly, PD transport increases [26]. Moreover, whereas SPCH-YFP does not move from cell to cell in wild-type plants, SPCH-YFP readily diffuses via PD in chorus mutants [26]. These findings support the conclusion that callose-mediated restriction of PD transport is required for epidermal patterning.

Similar to chorus, plants with a recessive allele of KOBITO1 form clusters of guard cells and have increased PD transport permitting diffusion of SPCH [27]. Unlike chorus, however, kobito1 mutants do not show defects in callose deposition at PD, and may even overproduce callose. KOBITO1 is a putative glycosyltransferase-like protein of unknown function previously implicated in cellulose biosynthesis [30,31]. Mutants defective in cellulose biosynthesis do not show kob1-like phenotypes, however, suggesting that KOBITO1 functions in another, as yet uncharacterized pathway restricting PD movement.

PD Regulate Plant Development: Root Tissue Differentiation

A screen for Arabidopsis mutants with aberrant root development found that callose deposition at PD plays a significant regulatory role in root patterning [32]. A dominant mutation (cals3-d) in GSL12, which like GSL8 encodes a putative callose synthase, causes increased callose deposition specifically in the cell wall surrounding PD. This decreases PD transport and prevents intercellular movement of the SHORT-ROOT (SHR) transcription factor and a regulatory small RNA, miRNA156. This is a clear demonstration that SHR indeed transports between cells through PD, a final confirmation after more than a decade of research on the mode of SHR movement [33,34].

Callose-mediated regulation of PD transport is also controlled by enzymes that degrade callose at PD, thereby increasing PD transport [29]. A recent study found that misexpression of these enzymes, called PD-localized β-1,3 glucanases (PDBGs), impacts lateral root formation [35]. During lateral root primordia formation, PD transport in the primordia becomes more and more restricted as callose accumulates at PD. Correspondingly, loss of PDBG function—increasing levels of callose at PD—causes ectopic lateral root formation, and overexpression of PDBGs decreases lateral root formation [35]. Future work is needed to identify the mobile signals regulated by callose-mediated restriction of PD transport to promote lateral root formation. These signals may include transcription factors, small RNAs, or phytohormones (such as auxin, known to accumulate at sites of lateral root formation) [36].

Transcription Factors Frequently Traffic Through Plasmodesmata

Early work on leaf, root, and meristem development uncovered a handful of key transcription factors that move from cell to cell. Currently, transcription factor movement appears to be the rule rather than the exception. Several reviews have described advances in our knowledge of the movement of transcription factors, small RNAs, and viruses through PD [1,17,33,34,37,38]; here we briefly summarize a few notable new reports.

Transcription factors move via PD through one of two broad pathways: either the protein moves diffusively through PD, analogous to GFP transport [6,39], or movement is facilitated by another molecule (such as a PD protein) [33,34]. Some transcription factors contain small domains or even specific residues required for their intercellular transport, such as the “intercellular trafficking motif” found in Dof family transcription factors that promotes PD transport [40]. It remains unclear if this domain interacts with a PD protein that facilitates transport or promotes movement through another mechanism.

Generally, transcription factor movement in roots strongly correlates with protein size, suggesting that diffusion is the typical mechanism for transcription factor movement [41]. Since many transcription factors are small enough to freely diffuse through PD, and several families of larger transcription factors include domains that promote PD trafficking, we can conclude that PD-mediated transcription factor movement is widespread. Indeed, when 76 transcription factors were tagged with mCherry and ectopically expressed in the root cortex and endodermis, 22 trafficked through PD [41]. This probably considerably underestimates transcription factor movement, since tagging proteins with the fluorophore mCherry (29 kDa) likely restricts the movement of larger proteins. Extrapolating from the results of these reports [33,34,40–42], hundreds of the ~2,000 transcription factors in Arabidopsis likely traffic through PD.

Plasmodesmal Proteins Coordinate Plant Defense Responses

Early studies of PD using transmission electron microscopy recognized that PD contain electron-dense components likely representing PD proteins. Until recently, however, very few PD-localized proteins had been identified, and their functions at PD remained elusive. Following years of concerted efforts to isolate PD for proteomic analysis, Fernández-Calvino et al. published the first draft of an Arabidopsis PD proteome representing 1,260 genes [43]. This list likely includes many false positives (one-quarter of these proteins have predicted mitochondrial and/or plastid transit peptides), and the full array of PD proteins are not represented (PD were isolated from only one cell type, excluding PD proteins that may be expressed under different conditions). Nonetheless, this PD proteome is an excellent starting point to guide future efforts.

Table 1 lists newly identified PD proteins (for previously identified PD proteins, see [16]). Here we highlight a few recently discovered PD proteins that have clear implications in plant responses to pathogens. PD-LOCALIZED PROTEIN 5 (PDLP5) is one of an eight-member family of proteins with strong homology to PDLP1 [20,44,45]. Like PDLP1, PDLP5 is a membrane-anchored protein that contains two Gnk2-homologous domains with unknown molecular function. PDLP5 was first identified as one of a small number of genes induced by infection with the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae [46,47]. PDLP5 overexpression causes decreased PD transport, likely by promoting callose deposition at PD in an SA-dependent pathway [20,21]. Native PDLP5 expression is associated with increased defense against Pseudomonas syringae and TMV, presumably due to increased production of ROS and SA in chloroplasts and decreased PD transport limiting TMV spread [48,49].

Table 1.

Newly Identified Plasmodesmal Localized Proteins*

| Protein Name | Protein Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| GLUCAN SYNTHASE-LIKE 12 (GSL12)* | Putative callose synthase, negatively regulates PD transport | [29,32] |

| LYSIN MOTIF DOMAIN-CONTAINING GPI-ANCHORED PROTEIN 2 (LYM2)* | Receptor-like protein, negatively regulates PD transport in response to chitin | [45] |

| PD GERMIN-LIKE PROTEIN 1, 2 (PDGLP1,2) | Positively regulate PD transport | [58] |

| NETWORKED 1A (NET1A) | Actin-binding protein | [60] |

| CLAVATA1 (CLV1) | Receptor-like kinase, regulates stem cell identity, forms multimeric complexes with ARABIDOPSIS CRINKLY 4 (ACR4) at PD | [61] |

| β-1,6-N-ACETYLGLUCOSAMINYL TRANSFERASE-LIKE ENZYME (GnTL) | Glycosyltransferase-like protein | [62] |

See text for more details on select proteins.

Another recently identified protein that preferentially localizes to PD, LYSIN MOTIF DOMAIN-CONTAINING GPI-ANCHORED PROTEIN (LYM2), is a receptor-like protein that triggers restriction of PD movement in response to chitin, a fungal pathogen-associated molecular pattern [50]. Knockout lym2 mutants do not decrease PD transport in the presence of chitin, and they are indeed more susceptible to fungal pathogens. The discoveries of PDLP5 and LYM2, proteins that confer resistance to plant pathogens, emphasize the crucial role of PD in plant defense [51].

Unanswered Questions

These advances in our knowledge of PD biology raise several new questions. We now have very strong evidence that callose accumulation at PD is a major mechanism restricting PD movement, and that aberrant callose deposition can cause myriad developmental defects. The discovery of dse1 demonstrates that other mechanisms can reduce PD transport, since dse1 has restricted intercellular movement without callose deposition near PD. Future studies on the signaling pathway connecting DSE1 with PD function and formation may provide new insights into PD regulation.

Most efforts to understand the relationship between PD transport and plant development have focused on transcription factor and small RNA movement. Phytohormones, however, can also transport from cell to cell via PD, and likely move more rapidly via diffusion through PD than other pathways, such as import/export through transporters at the plasma membrane [52]. How, then, are phytohormone concentration gradients maintained when phytohormones can rapidly diffuse through tissues via PD? The growing set of genetic tools for modulating PD function should allow for more direct studies on the relationship between phytohormone signaling and PD transport.

We still know very little about how PD form after cell division (“secondary PD”) [16,53]. The cell wall needs to allow new PD to be inserted between neighboring cells in a process distinct from PD formation at the cell plate during division, but how this happens remains unclear. New techniques to rapidly quantify the number of PD connecting cells will greatly benefit attempts to identify conditions or genetic alterations that impact PD formation [54]. The increased formation of secondary PD in leaves with silenced ISE1 or ISE2 expression may present a model system for future analyses [14,16]. Further studies of the putative cell wall enzyme KOBITO1 (kobito1 has increased PD transport, see above) and other cell wall modifying proteins on PD formation may provide answers.

Lastly, it is now clear that PD function and formation are tightly integrated with cellular physiology, with a particularly essential connection between PD and chloroplasts. Chloroplasts regulate PD function, as shown in several mutants and by physiological studies. Moreover, PD regulate chloroplast function, as demonstrated by the multiple effects on chloroplasts caused by altering expression of PD-localized proteins (P30 and PDLP5). Future PD research will continue to better characterize the mechanisms underlying these regulatory pathways that are central to plant development, defense, and vitality.

HIGHLIGHTS.

-

➢

Many proteins important for plasmodesmal transport do not localize to plasmodesmata.

-

➢

Signals from chloroplasts regulate plasmodesmata function and formation

-

➢

Changes in plasmodesmal transport disrupt chloroplast function.

-

➢

Hundreds of plant transcription factors likely move cell-to-cell via plasmodesmata.

-

➢

Plasmodesmata play a prominent role in plant development and defense.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Jacob O. Brunkard and Anne M. Runkel are supported by NSF predoctoral fellowships. Plasmodesmata research in the Zambryski lab is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM45244.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Niehl A, Heinlein M. Cellular pathways for viral transport through plasmodesmata. Protoplasma. 2011;248:75–99. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maule AJ, Benitez-Alfonso Y, Faulkner C. Plasmodesmata – membrane tunnels with attitude. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim I, Hempel FD, Sha K, Pfluger J, Zambryski PC. Identification of a developmental transition in plasmodesmatal function during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2002;129:1261–1272. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.5.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raven JA. Evolution of plasmodesmata. In: Oparka KJ, editor. Plasmodesmata. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2005. pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liarzi O, Epel BL. Development of a quantitative tool for measuring changes in the coefficient of conductivity of plasmodesmata induced by developmental, biotic, and abiotic signals. Protoplasma. 2005;225:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s00709-004-0079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford KM, Zambryski PC. Subcellular localization determines the availability of non-targeted proteins to plasmodesmatal transport. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1032–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00657-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobayashi K, Otegui MS, Krishnakumar S, Mindrinos M, Zambryski P. INCREASED SIZE EXCLUSION LIMIT 2 encodes a putative DEVH box RNA helicase involved in plasmodesmata function during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1885–1897. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stonebloom S, Burch-Smith T, Kim I, Meinke D, Mindrinos M, Zambryski P. Loss of the plant DEAD-box protein ISE1 leads to defective mitochondria and increased cell-to-cell transport via plasmodesmata. Proc Nat Aca Sci USA. 2009;106:17229–17234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909229106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burch-Smith TM, Brunkard JO, Choi YG, Zambryski PC. Organelle-nucleus cross-talk regulates plant intercellular communication via plasmodesmata. Proc Nat Aca Sci USA. 2011;108:e1451–e1460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117226108.. ** Embryo defective mutants increased size exclusion limit (ise) 1 and ise2 cause increased PD function and formation. ISE1 and ISE2 are RNA helicases that localize to mitochondria and plastids, respectively. Comparative whole-genome expression analyses and cytological studies of ise1 and ise2 seeds reveal that both mutants share remarkable defects in chloroplast biogenesis and plastid-related signaling pathways. The authors propose a new signaling pathway, Organelle-Nucleus-PD Signaling (ONPS).

- 10.Xu M, Cho E, Burch-Smith TM, Zambryski P. Plasmodesmata formation and cell-to-cell transpo8rt function are reduced in decreased size exclusion limit during embryogenesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Nat Aca Sci USA. 2012;109:5098–5103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202919109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benitez-Alfonso Y, Cilia M, San Roman A, Thomas C, Maule A, Hearn S, Jackson D. Control of Arabidopsis meristem development by thioredoxin-dependent regulation of intercellular transport. Proc Nat Aca Sci USA. 2009;106:3615–3620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808717106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu XM, Wang J, Xuan Z, Goldshmidt A, Borrill PGM, Hariharan N, Kim JY, Jackson D. Chaperonins facilitate KNOTTED1 cell-to-cell trafficking and stem cell function. Science. 2011;333:1141–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1205727.. *The authors show that CCT8, a chaperonin subunit, is required for proper folding of the KNOTTED1 transcription factor following its movement through PD. CCT8 does not associate with PD, however, and we do not know whether KN1 is actively misfolded at PD to facilitate its movement or, more simply, can only traffic through PD in a misfolded state.

- 13.Fichtenbauer D, Xu XM, Jackson D, Kragler F. The chaperonin CCT8 facilitates spread of tobamovirus infection. Plant Signal & Behav. 2012;7:318–321. doi: 10.4161/psb.19152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burch-Smith TM, Zambryski PC. Loss of INCREASED SIZE EXCLUSION LIMIT (ISE)1 or ISE2 increases the formation of secondary plasmodesmata. Curr Biol. 2010;20:989–993. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stonebloom S, Brunkard JO, Cheung AC, Jiang K, Feldman LJ, Zambryski PC. Redox states of plastids and mitochondria differentially regulate intercellular transport via plasmodesmata. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:190–199. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.186130.. * Previous reports found that reactive oxygen species (ROS) production could be associated with increased or decreased PD transport. By specifically triggering ROS production in either chloroplasts or mitochondria, this study shows that PD transport is affected differently depending on the intracellular site of ROS production. Thus, distinct signaling pathways involving ROS regulate intercellular movement.

- 16.Burch-Smith TM, Zambryski PC. Plasmodesmata paradigm shift: Regulation from without versus within. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:2.1–2.22. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harries P, Ding B. Cellular factors in plant virus movement: at the leading edge of macromolecular trafficking in plants. Virology. 2011;411:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhat S, Folimonova SY, Cole AB, Ballard KD, Lei Z, Watson BS, Sumner LW, Nelson RS. Influence of host chloroplast proteins on Tobacco mosaic virus accumulation and intercellular movement. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:134–147. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.207860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao J, Liu Q, Zhang H, Jia Q, Hong Y, Liu Y. The rubisco small subunit is involved in tobamovirus movement and Tm-22-mediated extreme resistance. Plant Physiol. 2013;161:374–383. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.209213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee J-Y, Wang X, Cui W, Sager R, Modla S, Czymmek K, Zybaliov B, van Wijk K, Zhang C, Lu H, et al. A plasmodesmata-localized protein mediates crosstalk between cell-to-cell communication and innate immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3353–3373. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.087742.. * PD-LOCATED PROTEIN 5 (PDLP5) overexpression demonstrates the role of PDLP5 in regulating PD and plant immunity. PDLP5 localizes to PD, when overexpressed, causes increased callose accumulation at PD and reduced PD transport. PDLP5 overexpression also causes hyperaccumulation of salicylic acid, reduced spread of tobacco mosaic virus, and resistance against pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae.

- 21.Wang X, Sager R, Cui W, Zhang C, Lu H, Lee JY. Salicylic acid regulates plasmodesmata closure during innate immune responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.110676. http://dx.doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.110676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildermuth MC, Dewdney J, Wu G, Ausubel FM. Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature. 2001;414:562–565. doi: 10.1038/35107108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conti G, Rodriguez MC, Manacorda CA, Asurmendi S. Transgenic expression of Tobacco mosaic virus capsid and movement proteins modulate plant basal defense and biotic stress responses in Nicotiana tabacum. Mol Plant–Micro Interact. 2012;25:1370–1384. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-12-0075-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolf S, Lucas WJ. Plasmodesmal-mediated plant communication network: implications for controlling carbon metabolism and resource allocation. In: Foyer CH, Quick WP, editors. A Molecular Approach to Primary Metabolism in Higher Plants. Taylor & Francis Ltd; 1997. pp. 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. Mechanisms of stomatal development. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:591–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guseman JM, Lee JS, Bogenschutz NL, Peterson KM, Virata RE, Xie B, Kanaoka MM, Hong Z, Torii KU. Dysregulation of cell-to-cell connectivity and stomatal patterning by loss-of-function mutation in Arabidopsis chorus (glucan synthase-like 8) Development. 2010;137:1731–1741. doi: 10.1242/dev.049197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kong D, Karve R, Willet A, Chen MK, Oden J, Shpak ED. Regulation of plasmodesmatal permeability and stomatal patterning by the glycosyltransferase-like protein KOBITO1. Plant Physiol. 2012;159:156–168. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.194563.. * The authors show that PD transport increases in kobito1 mutants. Increased PD-mediated trafficking of SPEECHLESS (SPCH) in kobito1 suggests that regulation of stomatal patterning is due to transport of transcription factors through PD. Based on its homology to glycosyltransferases, the authors speculate that KOBITO1 modifies cell wall biochemistry leading to changes in PD function or formation.

- 28.Chen XY, Liu L, Lee E, Han X, Rim Y, Chu H, Kim SW, Sack F, Kim JY. The Arabidopsis callose synthase gene GSL8 is required for cytokinesis and cell patterning. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:105–113. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zavaliev R, Ueki S, Epel BL, Citovsky V. Biology of callose (β-1,3-glucan) turnover at plasmodesmata. Protoplasma. 2011;248:117–130. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0247-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pagant S, Bichet A, Sugimoto K, Lerouxel O, Desprez T, Mccann M, Lerouge P, Vernhettes S, Höfte H. KOBITO1 encodes a novel plasma membrane protein necessary for normal synthesis of cellulose during cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2001–2013. doi: 10.1105/tpc.002873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brocard-Gifford I, Lynch TJ, Garcia ME, Malhotra B, Finkelstein RR. The Arabidopsis thaliana ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE8 locus encodes a novel protein mediating abscisic acid and sugar responses essential for growth. Plant Cell. 2004;16:406–421. doi: 10.1105/tpc.018077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vatén A, Dettmer J, Wu S, Stierhof Y-D, Miyashima S, Yadav SR, Roberts CJ, Campilho A, Bulone V, Lichtenberger R, et al. Callose biosynthesis regulates symplastic trafficking during root development. Dev Cell. 2011;21:1144–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.006.. ** This study identifies GLUCAN SYNTHASE-LIKE 12 (GSL12) as a regulator of PD-mediated transport of SHORT-ROOT and microRNA165 between the stele and endodermis in the root meristem. A gain-of-function mutation in GSL12 accumulates large amounts of callose in the extracellular space surrounding PD, causing abnormal root cell differentiation due to restricted movement of SHORT-ROOT and miRNA165.

- 33.Wu S, Gallagher KL. Mobile protein signals in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2011;14:563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu S, Gallagher KL. Transcription factors on the move. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2012;15:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benitez-Alfonso Y, Faulkner C, Pendle A, Miyashima S, Helariutta A, Maule A. Symplastic intercellular connectivity regulates lateral root patterning. Dev Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.010. ** Lateral root formation is a critical developmental process in plants and has been extensively studied, with intense focus on the role of auxin in lateral root primordia formation. In this study, the authors report that lateral root primordia formation correlates with callose-mediated restriction of PD transport. Furthermore, genetic alteration of callose deposition at PD is sufficient to induce or inhibit lateral root formation. These discoveries will make an important contribution to ongoing efforts to understand which factors (other than auxin) contribute to lateral root development, and how auxin maxima form at sites of lateral root primordia formation [36].

- 36.Petricka JJ, Winter CM, Benfey PN. Control of Arabidopsis root development. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:563–590. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molnar A, Melnyk C, Baulcombe DC. Silencing signals in plants: a long journey for small RNAs. Genome Biol. 2011;12:215. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furuta K, Lichtenberger R, Helariutta Y. The role of mobile small RNA species during root growth and development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu X, Dinneny JR, Crawford KM, Rhee Y, Citovsky V, Zambryski PC, Weigel D. Modes of intercellular transcription factor movement in the Arabidopsis apex. Development. 2003;130:3735–3745. doi: 10.1242/dev.00577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H, Ahmad M, Rim Y, Lucas WJ, Kim J-Y. Evolutionary and molecular analysis of Dof transcription factors identified a conserved motif for intercellular protein trafficking. New Phytol. 2013;198:1250–1260. doi: 10.1111/nph.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rim Y, Huang L, Chu H, Han X, Cho WK, Jeon CO, Kim HJ, Hong J-C, Lucas WJ, Kim JY. Analysis of Arabidopsis transcription factor families revealed extensive capacity for cell-to-cell movement as well as discrete trafficking patterns. Mol Cells. 2011;32:519–526. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0135-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J-Y, Colinas J, Wang JY, Mace D, Ohler U, Benfey PN. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of transcription factor expression in Arabidopsis roots. Proc Nat Aca Sci USA. 2006;103:6055–6060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510607103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandez-Calvino L, Faulkner C, Walshaw J, Saalbach G, Bayer E, Benitez-Alfonso Y, Maule A. Arabidopsis plasmodesmal proteome. PloS One. 2011;6:e18880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thomas CL, Bayer EM, Ritzenthaler C, Fernández-Calvino L, Maule AJ. Specific targeting of a plasmodesmal protein affecting cell-to-cell communication. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amari K, Boutant E, Hofmann C, Schmitt-Keichinger C, Fernandez-Calvino L, Didier P, Lerich A, Mutterer J, Thomas CL, Heinlein M, et al. A family of plasmodesmal proteins with receptor-like properties for plant viral movement proteins. PLoS Path. 2010;6:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bautor J, Parker JE. Salicylic acid – independent ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 signaling in Arabidopsis immunity and cell death is regulated by the monooxygenase FMO1 and the nudix hydrolase NUDT7. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1038–1051. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee MW, Jelenska J, Greenberg JT. Arabidopsis proteins important for modulating defense responses to Pseudomonas syringae that secrete HopW1-1. Plant J. 2008;54:452–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krasavina MS, Malyshenko SI, raldugina GN, Burmistrova NA, Nosov AV. Can salicylic acid affect the intercellular transport of the Tobacco mosaic virus by changing plasmodesmal permeability? Russ J Plant Physiol. 2002;49:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serova VV, Raldugina GN, Krasavina MS. Inhibition of callose hydrolysis by salicylic acid interferes with tobacco mosaic virus transport. Doklady Biochem and Biophys. 2006;406:36–39. doi: 10.1134/s1607672906010108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Faulkner C, Petutschnig E, Benitez-Alfonso Y, Beck M, Robatzek S. LYM2-dependent chitin perception limits molecular flux via plasmodesmata. Proc Nat Aca Sci USA. 2013;110:9166–9170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203458110.. * This study finds that a receptor-like protein localizes at PD and triggers plant immune responses in response to chitin, uncovering a new important role for PD in plant defense. LYSIN MOTIF DOMAIN-CONTAINING GPI-ANCHORED PROTEIN 2 (LYM2) is a PD-localized chitin receptor that reduces PD transport in the presence of chitin, a fungal pathogen-associated molecular pattern. Thus, receptors at PD directly coordinate plant defenses against fungal pathogens.

- 51.Lee JY, Lu H. Plasmodesmata: the battleground against intruders. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:201–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rutschow HL, Baskin TI, Kramer EM. Regulation of solute flux through plasmodesmata in the root meristem. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1817–1826. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.168187.. * This study uses small fluorescent tracers to measure rates of PD transport in roots. By assaying PD transport without mechanically damaging the root tissue, the authors show that the rate of solute movement through PD is at least an order of magnitude greater than previously reported. These higher transport rates imply that small signaling molecules, such as auxin, likely diffuse much more rapidly through the symplast than by plasma membrane-bound carriers, hinting that PD might regulate development through control of phytohormone diffusion.

- 53.Burch-Smith TM, Stonebloom S, Xu M, Zambryski PC. Plasmodesmata during development: re-examination of the importance of primary, secondary, and branched plasmodesmata structure versus function. Protoplasma. 2011;248:61–74. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0252-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fitzgibbon J, Beck M, Zhou J, Faulkner C, Robatzek S, Oparka K. A developmental framework for complex plasmodesmata formation revealed by large-scale imaging of the Arabidopsis leaf epidermis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:57–70. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tilsner J, Amari K, Torrance L. Plasmodesmata viewed as specialised membrane adhesion sites. Protoplasma. 2011;248:39–60. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Botha CEJ, Cross RHM, Bel AJE, Peter CI. Phloem loading in the sucrose-export-defective (SXD-1) mutant maize is limited by callose deposition at plasmodesmata in bundle sheath—vascular parenchyma interface. Protoplasma. 2000;214:65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Provencher LM, Miao L, Sinha N, Lucas WJ. Sucrose export defective1 encodes a novel protein implicated in chloroplast-to-nucleus signaling. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1127–1141. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.5.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ham B-K, Li G, Kang B-H, Zeng F, Lucas WJ. Overexpression of Arabidopsis plasmodesmata germin-like proteins disrupts root growth and development. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3630–3648. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.101063.. * Two PD-localized proteins, PDGLP1 and PDGLP2, increase PD transport through unknown mechanisms when overexpressed. Changes in PDGLP expression cause pleiotropic phenotypes: pdglp1 mutants have waxy stems lacking trichomes and decreased seed production [59], while 35S::PDGLP plants have shortened primary roots, lengthened lateral roots, and disorganized root meristems.

- 59.Kuromori T, Wada T, Kamiya A, Yuguchi M, Yokouchi T, Imura Y, Takabe H, Sakurai T, Akiyama K, Hirayama T, et al. A trial of phenome analysis using 4000 Ds-insertional mutants in gene-coding regions of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;47:640–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deeks MJ, Calcutt JR, Ingle EKS, Hawkins TJ, Chapman S, Richardson AC, Mentlak DA, Dixon MR, Cartwright F, Smertenko AP, et al. A superfamily of actin-binding proteins at the actin-membrane nexus of higher plants. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1595–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stahl Y, Grabowski S, Bleckmann A, Kühnemuth R, Weidtkamp-Peters S, Pinto KG, Kirschner GK, Schmid JB, Wink RH, Hülsewede A, et al. Moderation of Arabidopsis root stemness by CLAVATA1 and ARABIDOPSIS CRINKLY4 receptor kinase complexes. Curr Biol. 2013;23:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zalepa-King L, Citovsky V. A plasmodesmal glycosyltransferase-like protein. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]