Abstract

Rejection and infection are important adverse events after pediatric liver transplantation, not previously subject to concurrent risk analysis. Of 2291 children (<18 years), rejection occurred at least once in 46%, serious bacterial/fungal or viral infections in 52%. Infection caused more deaths than rejection (5.5% vs. 0.6% of patients, p <0.001). Early rejection (<6 month) did not contribute to mortality or graft failure. Recurrent/chronic rejection was a risk in graft failure, but led to retransplant in only 1.6% of first grafts. Multivariate predictors of bacterial/fungal infection included recipient age (highest in infants), race, donor organ variants, bilirubin, anhepatic time, cyclosporin (vs. tacrolimus) and era of transplant (before 2002 vs. after 2002); serious viral infection predictors included donor organ variants, rejection, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) naivety and era; for rejection, predictors included age (lowest in infants), primary diagnosis, donor-recipient blood type mismatch, the use of cyclosporin (vs. tacrolimus), no induction and era. In pediatric liver transplantation, infection risk far exceeds that of rejection, which causes limited harm to the patient or graft, particularly in infants. Aggressive infection control, attention to modifiable factors such as pretransplant nutrition and donor organ options and rigorous age-specific review of the risk/benefit of choice and intensity of immunosuppressive regimes is warranted.

Keywords: Infection, liver transplantation, pediatric, rejection, risk factors

Background

In pediatric liver transplantation, improved patient and graft survival is attributed to advances in surgery and improved immunosuppression regimens (1). Advances in immunosuppression have been concentrated on preventing rejection, and indeed the use of such agents has led to a decreased rate of acute cellular rejection and graft loss from rejection (2). However, potent immunosuppression imparts a risk for life-threatening infection and other adverse effects. One challenge for the physician managing children after liver transplant is to balance these risks. Outcomes might be improved if modifiable risks are better characterized. Unfortunately, no large-scale studies have concurrently evaluated outcomes and risk factors for both rejection and all types of infection. The imperative for such a study is emphasized by recent data, which suggest that morbidity and mortality from infections in children after liver transplantation may exceed those for rejection (3,4).

Methods

Patient population

All children receiving their first transplant enrolled in the SPLIT Registry between 1995 and 2006 were included in this data analysis. All SPLIT centers have Institutional Review Board approval and individual informed consent is obtained from parents and/or guardians (5–7). Coded information is submitted to the SPLIT data-coordination center at the time of listing for liver transplant (LT). Follow-up data were submitted on a biannual basis pre- and post-LT in the first 2 years and yearly, thereafter. There is long-term reporting of data related to events such as LT, death, allograft rejection, posttransplant complications, including infections and serious viral infection [symptomatic Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease and EBV-related posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD)].

Data analysis

For this study, database elements pertaining to deaths and graft losses due to infection and rejection were analyzed and causes of death and graft failure tabulated, including probability of posttransplant patient and graft survival, probability of rejection, probability of bacterial and fungal infection in the first 30 days and probability of serious viral infection in the first 15 months posttransplant. These time periods were chosen for the purposes of the detailed risk analyses for infections, as they represent the peak periods for the development of these types of infections (5–10). Infants are defined as <1 year of age. Rejection was listed as occurrence of hyperacute, acute cellular or chronic rejection requiring specific treatment at any time after transplant. Serious infection was defined by culture-proven bacterial and fungal infections and culture, seroconversion on sequential serology or polymerase chain reaction-proven CMV disease, EBV disease and biopsy-confirmed PTLD. A wide range of potential demographic, illness severity, surgical and immunological risk factors were selected to be evaluated in a risk analysis for both rejection and infection, as defined above, including assessment of an era effect (before 2002 vs. after 2002).

Statistical methods

Patients were grouped into proportions experiencing each event. Kaplan–Meier probability estimates were used to predict patient and graft survival after LT. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed using the aforementioned risk factors for rejection and infection. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to test univariate and multivariate associations for rejection and for viral infections. The Logistic regression model was used for evaluating risk factors associated with bacterial/fungal infections. Factors significant at a p-value of 0.1 for bacterial, fungal or viral infections and 0.15 for rejection in the univariate analyses were used in the multivariate model. Next, a backward-elimination procedure was performed to obtain those risk factors that were significant at a p-value of 0.05 from the multivariate analysis. The likelihood-ratio test was used to test significance, and model simplification continued until the reduced model yielded significant worsening of fit at a p-value of 0.05 (SAS System for Windows, v 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

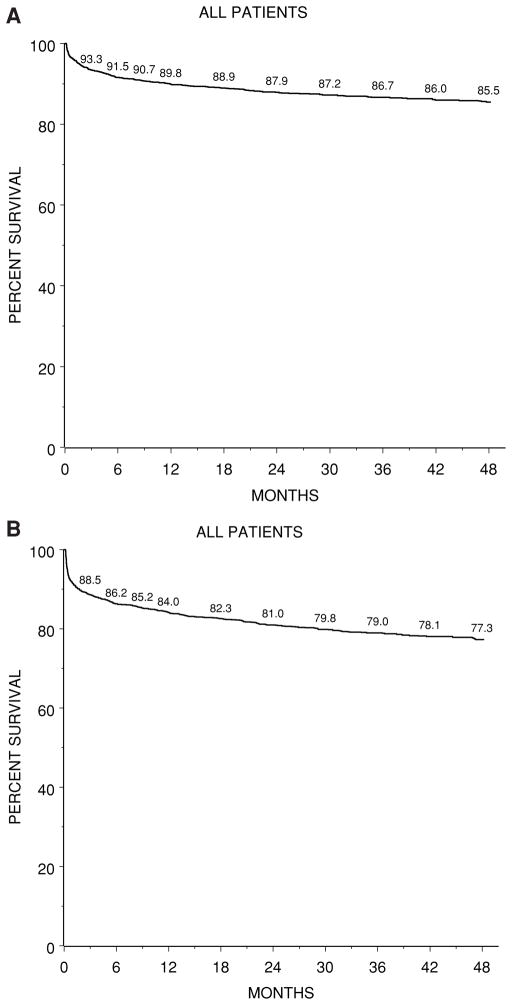

Patient and graft survival (Figure 1, Table 1)

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier probability of posttransplant survival after first liver transplant (N =2291).

(A) Overall patient survival, (B) first graft survival.

Table 1.

Mortality after liver transplantation in children, particularly with respect to rejection and infection

| Transplants (number) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 2291 | 236 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 2291 |

| Deaths | 200 | 63 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 274 (12% of patients) |

| Causes of Death | ||||||

| Infection (total) | 50 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 70, 26% of deaths (3.1% of patients) | |

| Bacterial | 25 | 11 | 3 | 39, 56% of infection deaths | ||

| Fungal | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7, 10% of infection deaths | ||

| PTLD | 9 | 2 | 0 | 11 PTLD, 16% of infection deaths | ||

| EBV Disease | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CMV disease | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Other | 8 | 1 | 0 | Total viral infection deaths = 13 (19% of infection deaths) | ||

| Multiorgan failure | 20 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 36 (13% of deaths) | |

| Cardiopulmonary | 25 | 7 | 2 | 34 (12% of deaths) | ||

| Renal failure | 1 | |||||

| Graft failure | 40 | 9 | 1 | 50 (18% of deaths) | ||

| Primary non-function | 9 | 4 | 13 (26% of deaths from graft) | |||

| Hepatic Artery Thrombosis | 9 | 9 (18% of deaths from graft) | ||||

| Recurrent disease | 9 | 1 | 10 (20% of deaths from graft) | |||

| Other liver failure | 9 | 4 | 1 | 14 (28% of deaths from graft) | ||

| Acute rejection | 2 | 2 (4% of deaths from graft) | ||||

| Chronic rejection | 2 | 2 (4% of deaths from graft) | ||||

| Brain injury | 27 | 5 | 2 | 34 (12% of deaths) | ||

| GI surgical complications | 4 | 3 | 1 | 8 (3% of deaths) | ||

| Malignancy | 14 | 1 | 15 (5% of deaths) | |||

| Other | 20 | 6 | ||||

Primary causes of death after first and subsequent transplants in 2291 children as listed in the SPLIT database. Expressed as number (n) and percentage (%) of total deaths after each transplant. Note that infection caused significantly more deaths than rejection (>16-fold).

Of 2291 patients enrolled in SPLIT who received their first transplant between January 1994 and May 2006, 9% (n = 200) died after their first transplant and 10% (n = 236) were retransplanted (Table 1). Of those receiving two to five transplants, a further 74 died (31% of retransplants). Thus, overall 274 patients have died (12% of total) and 2017 (88%) have survived. Actuarial patient survival after the first transplant, irrespective of the number of retransplants was 89.8% and 87.9% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (Figure 1A). After a second transplant these were 73.8% and 70.2% at 1 and 2 years, respectively (data not shown). Actuarial graft survival was 84.0% at 1 year and 77.3% at 4 years (Figure 1B).

Infection and rejection as causes of death

Table 1 tabulates the primary cause of death following first or subsequent transplants. Infection was the most common cause of death, listed as the primary cause of death in 70 patients (3.1% of all patients), the majority being due to bacterial sepsis (56%), with viral and fungal infections accounting for 19% and 10% of infection deaths, respectively. Infection accounted for 25% of first transplant deaths, 27% of second transplant deaths and 30% of third transplant deaths. Infection was also listed as contributing to death in another 74 patients whose primary cause of death was either multi-organ failure, cardiopulmonary failure or less commonly graft (liver) failure (data not shown). Infection therefore directly or indirectly contributed to the deaths of 125/2291 (5.5%) of patients, accounting for 125/274 (46%) of deaths.

In contrast, rejection directly or indirectly contributed to the deaths of 13/2291 (0.6%) of all patients, accounting for 13/274 (4.7%) of deaths. Rejection was the primary cause of death via graft failure in only 4 patients overall (0.2% of all patients, 1.5% of deaths), although rejection may have contributed to the death of another 9 patients, because rejection was the reason for retransplant in 36 patients, 9 of whom died after retransplant (see below). By univariate analysis, rejection was not a risk factor in mortality, including rejection in the first 6 months after transplant, and or comparison of 0 versus 1, or >1 versus 0 episodes of rejection overall (respective hazards ratios 0.986, 0.873 and 1.918, p-values = 0.94, 0.52 and 0.07, respectively).

Thus overall, there was a 10-fold greater risk of death from infection than from rejection (3.1% vs. 0.2% of patients or 46% vs. 4.7% of deaths, p < 0.001).

Other causes of death (Table 1) included multiorgan failure and cardiopulmonary failure (n = 127, 46% of all deaths), graft failure (either first or second graft) without the benefit of further retransplant (n = 50), brain injury (n = 27) and secondary malignancy (n = 14).

Infection and rejection as reasons for graft failure/re-transplant

As shown in Table 2, 236/2291 (10.3%) of patients receiving a primary graft had retransplants for graft failure, with vascular or surgical complications and primary graft non-function accounting for the majority (36% and 23%, respectively). Two retransplants were directly attributable to infection in the graft (hepatitis C). Rejection was a reason for graft failure and retransplant in 36/236 (15%) of the first retransplants, three-fourths of these for chronic rejection. It follows that most of the rejection was treatable, with only 1.6% of all patients requiring retransplant for graft failure due to rejection.

Table 2.

Causes of Graft Failure leading to Retransplantation after first and subsequent transplants in 2291 children as listed in the SPLIT database

| Transplants (number) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 2291 | 236 | 32 | 2 |

| Retransplanted | 236 | 32 | 2 | 1 |

| Primary reason for retransplant | ||||

| Primary graft dysfunction | 54 | 5 | ||

| Hyperacute rejection | 2 | |||

| Acute rejection | 8 | 1 | ||

| Chronic rejection | 26 | |||

| Ductopenic | 21 | 1 | ||

| Vascular | 5 | |||

| Vascular/postoperative complication | 84 | 14 | ||

| Hepatic artery thrombosis | 65 | 9 | 1 | |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 17 | 5 | 1 | |

| Postoperative hemorrhage | 2 | |||

| Biliary tract complication | 14 | |||

| Intrahepatic only | 5 | |||

| Intra and extrahepatic | 9 | 1 | ||

| Infection | ||||

| HCV infection | 2 | |||

| Poor compliance | 2 | |||

| Recurrent liver disease | 5 | |||

| Other | 17 | 7 | ||

Note that of 236 second transplants, rejection accounted for only 36/236 (15%) of the primary graft failures. There are 22/236 patients with missing primary reasons for the second transplant and 4/32 with missing primary reasons for the third transplant.

By univariate anlaysis, neither the occurrence of rejection episodes in the first 6 months after transplant or a comparison of 0 versus 1 episode of rejection predicted graft survival (respective hazards ratio 1.205, p = 0.24 and 1.096, p = 0.59). Comparing 0 and >1 episode of rejection, the hazards ratio, was 2.440, p = 0.006. In those patients receiving two or more retransplants for any reason, only two patients had further graft failures due to rejection and one of them had previous retransplantation due to rejection.

Thus, rejection in the first 6 months and single episodes of rejection did not contribute to graft failure, although recurrent rejection was a risk factor. Overall, rejection contributed to graft failure and retransplantation in only 36/2291 (1.6%) of all patients.

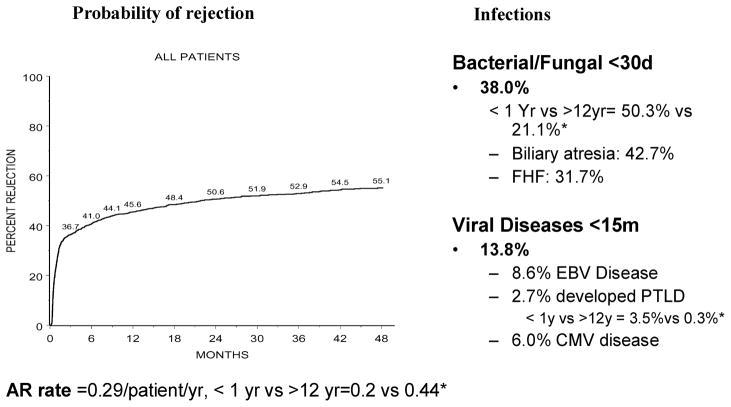

Rejection and infection rates (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Probability of rejection and infections over time in 2291 pediatric liver transplant recipients, expressed as percent of patients.

AR = acute rejection episodes; *compares rates in infants (age <1 year vs. adolescents age >12 years, all p < 0.001).

About 45% of patients developed at least one episode of rejection within 6 months of transplant, 38% developed serious bacterial or fungal infections (<30 days) and 14% had serious viral infections <15 months after liver transplant. There was a significant age-related variance in both infection and rejection rates. The rejection rate was 2-fold lower in those transplanted as infants compared with adolescents (0.20 vs. 0.44 episodes per patient year, p < 0.001), although the mean time to first rejection episode (156 ± 43 days vs. 103 ± 16 days posttransplant) was not statistically significant (p = 0.40). Conversely, the bacterial or fungal infection rate was highest in infants and lowest in adolescents (50% vs. 21%, p < 0.001), as was the viral infection rate (15% vs. 11%, p = 0.06).

Of the 762 bacterial infections documented, 39% were line infections, 35% were intra-abdominal, 18% were bacterial sepsis, 14% were wound infections, 17% were urinary infections, 13% were pneumonia and 7% were cholangitis.

Of the 189 fungal infections, 32% were intra-abdominal, 27% were urinary, 14% were line and 12% were lung infections.

For serious viral infections, the overall CMV disease rate was 6% and the EBV disease rate was 8.6%, with a PTLD rate of 2.7%. About half those with CMV disease more common in the first 30 days (3%) developed this within the first 30 days, whereas most (90%) of those with EBV disease (8%) occurred beyond 30 days post-transplant. Adenovirus caused pneumonia or gastrointestinal illness in about 1% (n = 22). On univariate analysis, age was a significant risk factor in the development of CMV or EBV disease (data not shown), and the PTLD rate was 10-fold higher in patients transplanted as infants compared to that in adolescents (3.5% vs. 0.3%, p < 0.001). CMV and EBV serological status at the time of transplant was recorded in 2226 cases for CMV and 2157 cases for EBV. Of these, 64% were CMV-naive and 63% were EBV-naive children at the time of transplant. Of those <1 year of age, 70% were EBV-naive patients, based on serology, although some positives may have had passive maternal antibody. Of the seronegative patients, 14.6% of those CMV negative at transplant and 15.1% of those EBV negative at transplant developed overt viral infection (CMV or EBV disease) within the first 15 months posttransplant.

Risk factors for rejection

Of the 22 potential risk factors for rejection analyzed in the univariate model (data not shown), factors significant at 0.15 level included recipient’s age at transplant, gender, primary diagnosis, donor/organ type, primary immunosuppression (cyclosporine vs. tacrolimus), early use of monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies, era of transplant (before 2002 vs. after 2002), donor-recipient Blood Type Match, cold ischemia time, IV IG use in the first 7 days posttransplant and bilirubin level (continuous variable). Factors found not to be significant included gender, race, factors making up the PELD score, warm ischemia time, growth deficit, patient acuity status at transplant and a range of immunological factors, including donor age and donor recipient gender or race match. In the multivariate analysis, only age at transplant, primary diagnosis, IV IG use in the first week, era of transplant and cyclosporine versus tacrolimus-based immunosuppression remained as independent risk factors (Table 3, Part A). Of note is that liver transplantation in infancy has a very low rejection risk independent of other factors.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for (A) rejection, (B) bacterial/fungal infection and (C) serious viral infections after liver transplantation in children (n = 2291).

| A. Rejection

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Category

|

Outcome rejection

|

|||

| A | B (Reference) | Relative risk1 | p-Value | 95% CI2 | |

| Recipient’s age | 6–11 month | 0–5 month | 1.39 | 0.032 | (1.03, 1.87) |

| 1–4 years | 1.84 | <.0001 | (1.39, 2.45) | ||

| 5–12 years | 1.57 | 0.003 | (1.16, 2.12) | ||

| ≥13 years | 1.93 | <.0001 | (1.39, 2.67) | ||

| Primary diagnosis | Other cholestatic or metabolic | Biliary atresia | 0.83 | 0.037 | (0.69, 0.99) |

| Fulminant liver failure | 1.05 | 0.699 | (0.83, 1.31) | ||

| Cirrhosis | 0.89 | 0.408 | (0.67, 1.18) | ||

| Other | 0.75 | 0.040 | (0.57, 0.99) | ||

| Donor-recipient blood match | Compatible | Identical | 0.92 | 0.430 | (0.75, 1.13) |

| Incompatible | 0.55 | 0.028 | (0.32, 0.94) | ||

| First immunosuppression | Cyclosporine | Tacrolimus | 1.49 | <.0001 | (1.27, 1.74) |

| IV IG use within the first week post-Tx | Yes | No | 0.75 | 0.002 | (0.62, 0.89) |

| Year of transplant | ≥2002 | ≤2001 | 0.69 | <.0001 | (0.60, 0.81) |

| B. Bacterial/fungal infection

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Category

|

Outcome infection

|

|||

| A | B (Reference) | Odds Ratio | p-Value | 95% CI2 | |

| Recipient’s age | 6–11 months | 0–5 months | 1.450 | 0.1066 | (0.923, 2.276) |

| 1–4 years | 1.052 | 0.8221 | (0.674, 1.644) | ||

| 5–12 years | 0.701 | 0.1510 | (0.432, 1.138) | ||

| ≥13 Years | 0.449 | 0.0053 | (0.256, 0.788) | ||

| Race | Black | White | 1.408 | 0.0553 | (0.992, 1.999) |

| Hispanic | 1.619 | 0.0035 | (1.172, 2.237) | ||

| Other | 1.423 | 0.1422 | (0.888, 2.278) | ||

| Donor/organ type | Cad-reduced | Whole | 1.744 | 0.0014 | (1.239, 2.454) |

| Cad-Split | 2.461 | <.0001 | (1.643, 3.686) | ||

| Live | 1.388 | 0.0885 | (0.952, 2.024) | ||

| First immunosuppression | Cyclosporine | Tacrolimus | 1.396 | 0.0419 | (1.012, 1.925) |

| Year of transplant | ≥2002 | ≤2001 | 0.703 | 0.0100 | (0.538, 0.919) |

| Log total bilirubin | Continuous predictor | 1.133 | 0.0213 | (1.019, 1.260) | |

| Log anhepatic time | Continuous predictor | 1.409 | 0.0153 | (1.068, 1.860) | |

| C. Viral infections

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Category

|

Outcome infection

|

|||

| A | B (Reference) | RR | p-Value | 95% CI2 | |

| Donor/organ type | Cad-reduced | Whole | 1.865 | 0.0005 | (1.254, 2.264) |

| Cad-split | 1.031 | 0.8899 | (0.671, 1,584) | ||

| Live | 1.188 | 0.3293 | (0.840, 1.680) | ||

| Year of transplant | ≥2002 | ≤2001 | 0.726 | 0.0134 | (0.563, 0.936) |

| Rejection Post-Tx | Yes | No | 1.705 | <0.0001 | (1.326, 2.192) |

| Pre-Tx recipient EBV serology | Positive | Negative | 0.730 | 0.0186 | (0.561, 0.949) |

Rejection is defined as treated episodes, bacterial or fungal infections as culture-proven infections in the first 30 days, and serious viral infections as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus disease or lymphoproliferative disease. Of 22 risk factors evaluated by univariate analysis, those significant at a p-value of 0.1 for bacterial, fungal or viral infections and 0.15 for rejection were used in the multivariate model, and a backward-elimination procedure was performed to obtain those significant risk factors depicted here (p-value >0.05).

Relative risk >1 implies patients in category A have higher risk of outcome compared with category B. Relative risks and the corresponding confidence intervals are adjusted for other factors in the model.

CI = Confidence intervals.

Risk factors for infection

For bacterial infections, significant factors in the univariate analysis included a wide range of demographic factors (age, race, primary diagnosis and era of transplant), severity factors (height and weight deficit, PELD score and its components, bilirubin, albumin and WBC levels at transplant, time on the waiting list, patient acuity status), surgical factors (prior abdominal surgery, donor organ type, anhepatic time) and immunological factors (rejection, donor age and cyclosporine vs. tacrolimus at initiation). In the multivariate analysis (Table 3, Part B), age, race, immunosuppression, year of transplant, bilirubin level and organ donor type were significant independent risk factors. Of note, infants had higher odds ratio for bacterial infections than adolescents. Those who received deceased donor split or reduced-sized liver also were at higher risk. The latter are more likely to be transplants in infants, thereby heightening this risk in this age group.

For viral infections, in the univariate analysis, significant risk factors included age, and were predominantly immunological, including rejection, cyclosporin use and era of transplant. Various disease severity factors were not significant, but as for bacterial infections, those who received deceased donor split or reduced-sized liver also were at higher risk. Of these significant factors in the univariate analysis, only rejection (relative risk 1.65), era of transplant and organ donor variants were significant in the multivariate analysis (Table 3, Part C).

Discussion

This analysis of data, derived from the largest cumulative dataset of pediatric liver transplants available, describes outcomes and risk factors in relation to rejection and infection, both important and potentially inter-related adverse events after liver transplantation. There is no similar concurrent analysis with which to compare these data, which provide a broad view of outcomes across centers in North America, although earlier less focussed analyses from the same database stimulated this concurrent study (2,3,11).

Both infection and rejection are relatively common occurrences, but these data confirm that the risk from infection far exceeds that from rejection, particularly in infants, a disparity that deserves detailed analysis. Rejection rarely contributed to and was not a risk factor in mortality, and the risk of graft failure from rejection was low, limited to chronic or recurrent rejection, which in itself was uncommon. Single episodes of rejection and rejection in the first 6 months were not predictors of graft failure, suggesting that acute cellular rejection was almost always treatable. In contrast, infection was the most common cause of death and clearly caused much more morbidity than rejection.

Young age was an important risk factor for infections, but a negative risk factor for rejection, and infants had half the rate of rejection, three times the rate of bacterial or fungal infection and 10 times the rate of PTLD compared with adolescents. These overall risk analysis findings were independent of the relative improvements in the risks of both rejection and infection when comparing before 2002 versus after 2002 (risk ratio = 0.7), which may be explained by improved immunosuppression choices and dose monitoring, and the trend to early steroid withdrawal and immunosuppression minimization (12). Other risk factors for bacterial and fungal infections included recipient severity of illness factors and surgical issues; and for serious viral infections, the primary immunosuppression used and rejection (presumably via increased immunosuppression). Collectively, these data raise the possibility that choice and/or intensity of primary immunosuppression are modifiable risk factors for infection, particularly for serious viral infections, and most particularly for infants. Certainly, avoiding over-immunosuppression by carefully monitoring calcinuerin inhibitor dosage and blood levels and limiting steroid use at least in this age group would be pertinent goals. Infants are innately in a state of immune immaturity, are more likely CMV and EBV naive, but pose much less of a threat for organ failure due to rejection, and could benefit from immunosuppression minimization. Thus, a rigorous age-specific review of the choice and intensity of immunosuppression, balanced against the relatively low risk of rejection is warranted in pediatric liver transplantation.

Of relevance to these data is the development and increasing use of newer, often more potent immunosuppressive regimens (12–18), for example induction agents, poly- or monoclonal antibodies, mycophenylate and sirolimus. It is unfortunate that most studies that use these newer agents often initially emphasize attaining an almost zero rejection rate, but have not included a detailed evaluation of infection risk (15–17). For example, substitution of CNIs by mTOR inhibitors such as sirolimus may be promising as a substitute for patients with calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity, but their use requires validation in long-term studies in large cohorts, particularly with regard to the increasingly reported risk of serious interstitial pneumonia and other infections (18,19). In addition, age responsiveness and risk seem critical when evaluating the use of new agents. For example, the use of mycophenylate or induction agents may be unnecessary in infants given their very low risk of rejection and more risky because of the innate immaturity of their immune system. In all age groups however, potent immunosuppressive regimens have other drawbacks (18,20) besides risk for infection, including malignancy, metabolic adverse effects, growth failure and late renal insufficiency.

A key question thus is, what level of rejection is acceptable? These data emphasize the concept of rejection risk (to the patient and graft) rather than rejection rate. While at least one episode of rejection occurred in about half the patients, the overall rejection rate was 0.29 episodes per patient year (0.20 in infants and 0.44 in adolescents), and only 1.5% of patients developed graft failure, with few patients dying directly or indirectly due to rejection. The era effect does indicate that rejection rates are now acceptably low and chronic rejection is almost absent in the tacrolimus era, confirming recent large single center analyses (21). Moreover, recent evidence suggests that the immune response toward a liver allograft is not necessarily always harmful. Some alloreactivity may actually facilitate graft tolerance, which clearly does occur in a significant number of patients (22,23), explained variously by the opposing theories of clonal exhaustion-deletion (24) or ‘alloimmune homeostasis’ (25). Infants are more ‘tolerogenic’, not entirely explained by these theories, as indicated by the clinical tolerance of ABO-incompatible organs in infant heart transplant recipients (26). A large study of outcomes from acute rejection in adult liver transplantation, where some rejection actually conveyed a graft outcome advantage, raised the question as to whether complete elimination of all rejection is really a desirable goal in liver transplantation (27). While there is some room for improvement in recurrent rejection as a risk factor for some graft loss, based on the graft failure data presented here, this has to be tempered by the overall risk to the patient. What may be required to make this improvement is not more potent immunosuppression but a more specific and perhaps ‘smarter individualized approach’. Questions such as, do infants need steroids, mycophenylate or induction therapy at all? How intensely should pediatric liver recipients be immunosuppressed? And in which recipients can immunosuppression be discontinued altogether, all require study. It is probably time to submit these to rigorous controlled trials, rather than submit to the trial and error approach of the past. Nonetheless, the data presented here give some confidence to the current emphasis toward immunosuppression minimization in pediatric liver recipients.

Other factors, including improvements in the ability to treat perioperative infection, monitoring for and preventing viral infections, and improved focus on transplantation when the child is in better condition are also emphasized as likely to be leading to improved outcomes and reducing deaths from infections. An individualized approach to the prevention of EBV disease and PTLD (28), would be particularly relevant to infants, given the high risk of these problems in CMV- or EBV-naive patients. Undernutrition is a well-documented risk factor, particularly in biliary atresia (3), modifiable by aggressive nutritional support (29,30). For reasons that are not immediately obvious, the type of donor organ (split, deceased donor cut-down and living donor organ vs. whole) appears to be a factor in both bacterial and viral infections, but not rejection. Surgical complications from the use of these donors may increase the potential for bacterial and fungal infections.

In conclusion, in pediatric liver transplantation, infection risk far exceeds that of rejection, which on current immunosuppression regimes causes limited harm to the patient or graft. Rigorous evaluation of the choice and intensity and monitoring of immunosuppression regimens in pediatric liver transplantation is indicated, especially in infant recipients, where infection risk is highest and rejection risk is lowest. The current trend toward immunosuppression minimization is supported by these data. However, anticipatory management and aggressive control of infection, and attention to modifiable factors such as pretransplant nutrition, and appropriate choice of donor organ options seems advisable. Any new immunosuppressive regime requires age-specific evaluation, and concurrent analysis of infection risk. Findings from this study may help in decision making in the choice of immunosuppressive regimens and call attention to the concept of reducing rejection risks rather than rates as a preferable goal in pediatric liver transplantation, balancing these risks against the risks of immunosuppression.

Acknowledgments

SPLIT is supported by NIDDK Grant #U01 DK061693–01A1 and an Educational Grant from Astellas. Dr Turmelle was a 2006–2007 Advanced Trainee in Hepatology supported by the American Liver Foundation.

References

- 1.Colombani PM, Dunn SP, Harmon WE, Magee JC, McDiarmid SV, Spray TL. Pediatric transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(Suppl 4):53–63. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.3.s4.6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin SR, Atkison P, Anand R, Lindblad AS SPLIT Research Group. Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation 2002: Patient and graft survival and rejection in pediatric recipients of a first liver transplant in the United States and Canada. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8:273–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Utterson EC, Shepherd RW, Sokol RJ, et al. Biliary atresia: Clinical profiles, risk factors, and outcomes of 755 patients listed for liver transplantation. J Pediatr. 2005;147:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jain A, Mazariegos G, Kashyap R, et al. Pediatric liver transplantation: A single center experience spanning 20 years. Transplantation. 2002;73:941–947. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200203270-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollenbeak CS, Alfrey EJ, Sheridan K, Burger TL, Dillon PW. Surgical site infections following pediatric liver transplantation: Risks and costs. Transpl Infect Dis. 2003;5:72–78. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2003.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quiros-Tejeira RE, Ament ME, McDiarmid SV, et al. Late-onset bacteremia in uncomplicated pediatric liver-transplant recipients after a febrile episode. Transpl Int. 2002;15(9–10):502–507. doi: 10.1007/s00147-002-0466-1. Epub 2002 Sep 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Their M, Holmberg C, Lautenschlager I, Hockerstedt K, Jalanko H. Infections in pediatric kidney and liver transplant patients after perioperative hospitalization. Transplantation. 2000;69:1617–1623. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200004270-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.George DL, Arnow PM, Fox A, et al. Patterns of infection after pediatric liver transplantation. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:924–929. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160200046024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sokal EM, Antunes H, Beguin C, et al. Early signs and risk factors for the increased incidence of Epstein-Barr virus-related post-transplant lymphoproliferative diseases in pediatric liver transplant recipients treated with tacrolimus. Transplantation. 1997;64:1438–1442. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199711270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mellon A, Shepherd RW, Faoagali JL, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection after liver transplantation in children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1993;8:540–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1993.tb01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDiarmid SV, Anand R SPLIT Research Group. Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT): A summary of the 2003 Annual Report. Clin Transpl. 2003:119–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McDiarmid SV, Anand R, Lindblad AS SPLIT Research Group. Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation: 2002 update. An overview of demographics, indications, timing, and immunosuppressive practices in pediatric liver transplantation in the United States and Canada. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8:284–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDiarmid SV, Anand R, Lindblad AS Principal Investigators and Institutions of the Studies of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT) Research Group. Development of a pediatric end-stage liver disease score to predict poor outcome in children awaiting liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:173–181. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200207270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Hussaini A, Tredger JM, Dhawan A. Immunosuppression in pediatric liver and intestinal transplantation: A closer look at the arsenal. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:152–165. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000172260.46986.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuller S, Wiederkehr JC, Coelho-Lemos IM, Avilla SG, Schultz C. Daclizumab induction therapy associated with tacrolimus-MMF has better outcome compared with tacrolimus-MMF alone in pediatric living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:1151–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heffron TG, Pillen T, Smallwood GA, Welch D, Oakley B, Romero R. Pediatric liver transplantation with daclizumab induction. Transplantation. 2003;75:2040–2043. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000065740.69296.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganschow R, Grabhorn E, Schulz A, Von Hugo A, Rogiers X, Burdelski M. Long-term results of basiliximab induction immunosuppression in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:741–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tredger JM, Brown NW, Dhawan A. Immunosuppression in pediatric solid organ transplantation: opportunities, risks, and management. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10:879–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2006.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Champion L, Stern M, Israel-Biet D, et al. Brief communication: Sirolimus-associated pneumonitis: 24 cases in transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:505–509. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bucuvalas JC, Campbell KM, Cole CR, Guthery SL. Outcomes after liver transplantation: keep the end in mind. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S41–S48. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000226389.64236.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain A, Mazariegos G, Pokharna R, et al. The absence of chronic rejection in pediatric primary liver transplant patients who are maintained on tacrolimus-based immunosuppression: A long-term analysis. Transplantation. 2003;75:1020–1025. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000056168.79903.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazariegos GV, Sindhi R, Thomson AW, Marcos A. Clinical tolerance following liver transplantation: Long term results and future prospects. Transpl Immunol. 2007;17:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.09.033. Epub 2006, Oct 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koshiba T, Li Y, Takemura M, et al. Clinical, immunological, and pathological aspects of operational tolerance after pediatric living-donor liver transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2007;17:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.10.004. Epub 2006, Nov 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starzl TE, Zinkernagel RM. Transplantation tolerance from a historical perspective. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:233–239. doi: 10.1038/35105088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J, Mathew JM, Esquenazi V. Toward tolerance to human organ transplants: A few additional corollaries and questions. Transplantation. 2004;77:940–942. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000117781.50131.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daebritz SH, Schmoeckel M, Mair H, Kozlik-Feldmann R, Wittmann G, Kowalski C, Kaczmarek I, Reichart B. Blood type incompatible cardiac transplantation in young infants. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.11.032. discussion 343. (Epub 2007, Jan 17.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiesner RH, Demetris AJ, Belle SH, et al. Acute hepatic allograft rejection: Incidence, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Hepatology. 1998;28:638–645. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee TC, Goss JA, Rooney CM, et al. Quantification of a low cellular immune response to aid in identification of pediatric liver transplant recipients at high-risk for EBV infection. Clin Transplant. 2006;20:689–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin SE, Shepherd RW, Cleghorn GJ, et al. Pre-operative nutritional support in children with end-stage liver disease accepted for liver transplantation: An approach to management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1990;5:566–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1990.tb01442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chin SE, Shepherd RW, Thomas BJ, et al. Nutritional support in children with end-stage liver disease: A randomized crossover trial of a branched-chain amino acid supplement. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:158–163. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]