Abstract

22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome (22q11DS) arises from an interstitial chromosomal microdeletion encompassing at least 30 genes. This disorder is one of the most significant known cytogenetic risk factors for schizophrenia, and can also cause heart abnormalities, cognitive deficits, hearing difficulties, and a variety of other medical problems. The Df1/+ hemizygous knockout mouse, a model for human 22q11DS, recapitulates many of the deficits observed in the human syndrome including heart defects, impaired memory, and abnormal auditory sensorimotor gating. Here we show that Df1/+ mice, like human 22q11DS patients, have substantial rates of hearing loss arising from chronic middle ear infection. Auditory brainstem response (ABR) measurements revealed significant elevation of click-response thresholds in 48% of Df1/+ mice, often in only one ear. Anatomical and histological analysis of the middle ear demonstrated no gross structural abnormalities, but frequent signs of otitis media (OM, chronic inflammation of the middle ear), including excessive effusion and thickened mucosa. In mice for which both in vivo ABR thresholds and post mortem middle-ear histology were obtained, the severity of signs of OM correlated directly with the level of hearing impairment. These results suggest that abnormal auditory sensorimotor gating previously reported in mouse models of 22q11DS could arise from abnormalities in auditory processing. Furthermore, the findings indicate that Df1/+ mice are an excellent model for increased risk of OM in human 22q11DS patients. Given the frequently monaural nature of OM in Df1/+ mice, these animals could also be a powerful tool for investigating the interplay between genetic and environmental causes of OM.

Introduction

22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome (22q11DS, OMIM #188400), also commonly known as DiGeorge Syndrome or Velo-Cardio-Facial Syndrome, is a genetic disorder that results from an approximately 1.5-3Mb congenital multigene deletion on the long arm of chromosome 22, which includes the gene for T-Box Transcription factor 1 (TBX1) [1,2]. 22q11DS occurs in 1:4000 live births, making it the most common interstitial deletion syndrome and the second most common chromosomal abnormality after Down's Syndrome [3]. Typical physical findings in 22q11DS patients include defects in cardiovascular [4], thymic, parathyroid and craniofacial [5] structures derived from the pharyngeal arches and pouches [6]. In addition, 22q11DS is associated with high frequencies (80–100%) of neurocognitive disabilities [7], and it is one of few cytogenetic abnormalities that occurs in tandem with a psychiatric disease [3]. The syndrome is one of the highest known risk factors for schizophrenia, as 25-30% of 22q11DS patients develop schizophrenia during adolescence or adulthood [8].

22q11DS is also a risk factor for development of otitis media (OM) [9]. OM is inflammation of the middle ear cavity (MEC), often presenting with pain and fever. It is the most common disease in young children worldwide, occurring at least once before the age of two in 90% of infants in the developed world [10]. OM is typically classified as either acute or chronic. Acute otitis media is associated with a bacterial infection and often resolves spontaneously within three months. However, in some cases acute OM is followed by otitis media with effusion (OME) that can become chronic [11]. OME is characterized by excessive effusion that accumulates in the MEC, and the absence of obvious signs of acute infection. Excessive effusion often leads to conductive hearing loss, which in severe cases can become permanent due to erosion of the middle ear ossicles [12] . Even in less severe cases, conductive hearing loss due to OME can interfere with speech and language development. The usual treatment and also the most common operation in the United Kingdom is the insertion of grommets into the tympanic membrane to permit ventilation and drainage of exudates from the MEC [13]. Risk factors for OM include infection, altered immune status, exposure to tobacco smoke, and anatomical defects such as cleft palate [14] . In addition, although the pathogenesis of OM is multifactorial, a role for genetic predisposition is increasingly recognized [15,16]. In 22q11DS, studies have shown that a majority of patients have a history of chronic or recurrent OM [17,18].

The hemizygous Df1-knockout mouse (Df1/+) was genetically engineered to be a model for human 22q11DS; it carries a multigene deletion in a region of mouse chromosome 16 that is orthologous to the 22q11.2 region in humans [19,20]. Although the region is highly conserved, several ancestral rearrangements have led to changes in gene order, and so the deletion in Df1/+ mice encompasses 18 of the protein-encoding genes deleted in human 22q11DS. Df1/+ mice have proven to be an excellent model for major developmental defects in human 22q11DS such as cardiovascular abnormalities [21] and thymic or parathyroid defects [22], although no gross craniofacial abnormalities such as cleft palate have been reported. Furthermore, both Df1/+ mice and other mouse models of 22q11DS have been found to show cognitive and behavioural abnormalities associated with human 22q11DS and schizophrenia, including reduced auditory sensorimotor gating [23-25]. Modern tests of sensorimotor gating depend on the ability to hear, and previous studies have presented some evidence for normal hearing in Df1/+ mice and similar mouse models [23-25]. However, mice heterozygous for Tbx1, one of the genes involved in the multigene deletion and the most likely candidate gene responsible for the pharyngeal arch-derived defects in 22q11DS, have been shown to suffer frequent middle ear inflammation with associated conductive hearing loss [26].

Here, we aimed to resolve this discrepancy in the literature, using auditory brainstem response (ABR) measurement to assess hearing capability in adult Df1/+ mice and their WT littermates. To obtain data from a large population of age-matched Df1/+ and WT mice, we focused on measurement of click-evoked ABR thresholds, a simple and rapid electroencephalographic measure of peripheral and early central auditory activity that could be obtained in vivo from each ear for all animals in a litter in a single day. We found that click-evoked ABR thresholds were significantly elevated in 48% of the Df1/+ animals, often in only one ear. Anatomical and histological analysis of the middle ear revealed a high incidence of OME in Df1/+ mice, which correlated directly with elevated ABR thresholds. We conclude that Df1/+ mice, like human 22q11DS patients, are susceptible to otitis media and conductive hearing loss. These results suggest that studies of abnormal auditory sensorimotor gating in Df1/+ mice need to be revisited using more sensitive assays for hearing loss, and also that Df1/+ mice are a potentially powerful animal model for studying the genetic and environmental causes of otitis media.

Results

Elevated ABR thresholds in both male and female Df1/+ mice

The auditory brainstem response is an electroencephalographic signal arising from sound-evoked activity in neuronal circuits of the ascending central auditory pathway. ABRs evoked by click stimuli were recorded in 44 Df1/+ mice (24 male, 20 female) and 43 WT littermates (24 male, 19 female), ranging in age from 8 to 40 weeks old. Measurements were taken once in each animal in either one or both ears, under free-field conditions with an ear plug in the opposite ear. Both left and right ears were tested in 31 of the Df1/+ and 23 of the WT animals, and one ear only in 13 Df1/+ and 20 WT mice. The ABR database therefore consisted of a total of 75 Df1/+ and 66 WT ABR recordings. Click ABR thresholds were determined for each recording, and judged to be the lowest click intensity at which characteristic peaks of the ABR waveform could be observed (Figure S1).

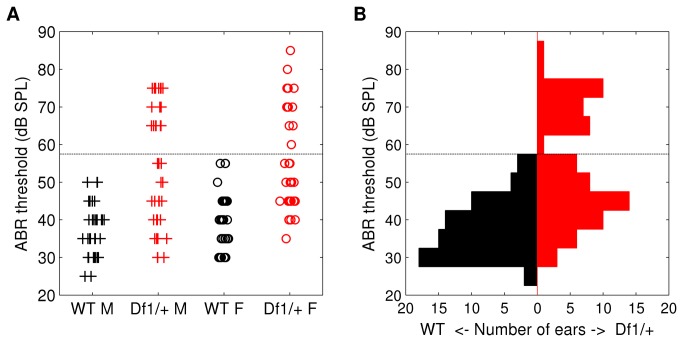

Click ABR thresholds were significantly higher on average, and also more variable, in both male and female Df1/+ mice than in their gender-matched WT littermates (Figure 1A). Median thresholds (and total ranges) were 35 (25-50) and 37.5 (30-55) dB SPL for male and female WT animals, respectively, but 50 (30-75) and 50 (35-85) for male and female Df1/+ mice from the same litters. Median thresholds therefore differed significantly between recordings from Df1/+ and WT mice of the same gender (Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test, Df1/+ versus WT: p=6x10-6 males, p=9x10-7 females), but not between males and females of the same genotype (Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test, males versus females: p=0.3 Df1/+, p=0.5 WT). Similar results were obtained when recordings from left or right ears were considered separately.

Figure 1. Elevated ABR thresholds, and bimodal distribution of thresholds, in Df1/+ mice.

(A) Click ABR thresholds recorded from individual ears in male and female WT (black) and Df1/+ (red) mice. Median ABR thresholds differed significantly between Df1/+ and WT mice of the same gender (Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test, Df1/+ versus WT: p=6x10-6 males, p=9x10-7 females), but not between males and females of the same genotype (Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test, males versus females: p=0.3 Df1/+, p=0.5 WT). (B) Click ABR thresholds pooled across recordings from male and female animals, to illustrate the bimodal appearance of the Df1/+ ABR threshold distribution. Dashed lines indicate the criterion threshold for a significant click ABR deficit (see text).

ABR threshold distribution in Df1/+ mice appears bimodal

Since there were no significant differences in click ABR thresholds recorded from male and female animals of the same genotype, we pooled data from male and female mice to examine genotype differences in the threshold distributions more closely (Figure 1B). The distribution of click ABR thresholds recorded from Df1/+ mice was significantly different from the distribution recorded from WT mice (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p=5x10-8), even when the two distributions were normalised to align the medians (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test on median-normalised data, p=0.02). In fact, the Df1/+ threshold distribution appeared bimodal, suggesting that ABR deficits were perhaps restricted to a subset of Df1/+ animals.

To be conservative, we defined a click ABR deficit to be present when the ABR threshold exceeded 55 dB SPL (criterion threshold indicated by dashed lines in Figure 1A and B), since 55 dB SPL was the highest threshold observed in recordings from WT mice. By definition, none of the ABR thresholds recorded in WT mice exceeded this criterion; however, 38% of thresholds recorded from the ears of Df1/+ mice did. Since elevated ABR thresholds could occur either in only one ear or in both ears, the percentage of affected animals could in principle differ from the percentage of affected ears. We investigated this issue with further analysis of ABR data from the subset of animals for which both left and right ear ABR recordings had been obtained.

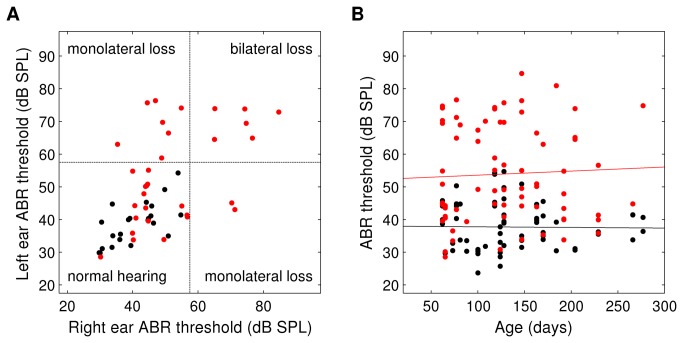

ABR deficit in Df1/+ mice can be either monaural or binaural

To determine whether click ABR thresholds tended to be similar in the two ears, we compared left and right ABR thresholds for the 31 Df1/+ and 23 WT animals for which ABR recordings had been collected from both ears (Figure 2A). The correlation between left and right ear ABR thresholds was lower in Df1/+ than WT mice (Pearson's r=0.49, p=0.006 for Df1/+ mice; r=0.68, p=0.0004 for WT mice), but not significantly so (Fisher transformation test for difference in correlation coefficients). Thus left and right ear ABR thresholds were correlated in both groups of animals. However, among the Df1/+ mice, 16 (52%) had no significant click ABR deficit in either ear, 9 (29%) had a significant deficit in one ear, and 6 (19%) had deficits in both ears. Thus, 48% of the Df1/+ mice had a click ABR deficit in at least one of the two ears, and the deficit was monolateral in 60% of those affected animals. This finding is suggestive of a conductive origin for the hearing loss, because most causes of sensorineural hearing loss would be expected to affect both ears.

Figure 2. ABR deficit in Df1/+ mice is often monolateral, and shows no age dependence.

(A) Click ABR thresholds recorded in left versus right ears, for WT (black) and Df1/+ (red) mice in which both ears were tested. Dashed line indicates criterion threshold for a significant click ABR deficit. (B) Click ABR thresholds versus age, for all ABR recordings. Solid lines indicate best-fit regression lines. Slopes were not significantly different from zero for recordings from either WT (black; slope 95% CI [-0.047, 0.072]) or Df1/+ (red; slope 95% CI [-0.072, 0.030]) animals. To ensure visibility of overlapped data points, zero-mean, 1 dB SPL standard-deviation Gaussian noise was added to threshold data in both A and B for display.

ABR deficit in adult Df1/+ mice shows no age dependence

The C57BL/6 background strain from which Df1/+ mice and their WT littermates are derived is known to have age-related sensorineural hearing loss, especially at high sound frequencies [27,28]. Mutations can accelerate age-related hearing loss, so we wondered if ABR deficits in Df1/+ mice might worsen with age in adulthood. However, we found no significant dependence of click ABR thresholds on age in adulthood, for either Df1/+ or WT mice (Figure 2B). Similar results were obtained whether the analysis was performed on all recorded ABR thresholds as shown in Figure 2B, or on thresholds from left ears or right ears separately. These results demonstrate that click ABR deficits in Df1/+ animals cannot be explained by aging-related effects, suggesting again that these deficits are likely to be primarily conductive in origin. However, since WT C57BL/6 animals would be expected to have age-related hearing loss for high sound frequencies, the negative results for WT animals also indicate that ABR thresholds for a broadband click stimulus are not a sufficiently sensitive assay to evaluate the possibility of high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss in addition to conductive loss (see Discussion).

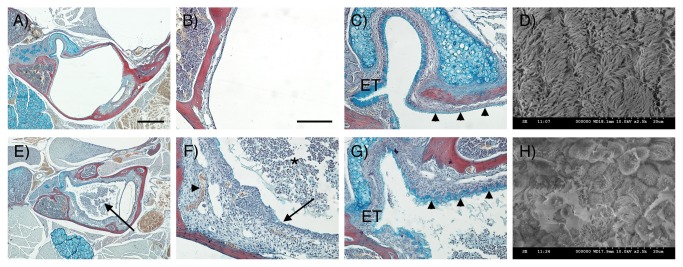

Adult Df1/+ mice have a high incidence of OM

To determine whether Df1/+ mice have middle ear problems, we first examined middle ear anatomy and histology in 9 Df1/+ mice and their WT littermates. The 9 Df1/+ mice included 6 animals with confirmed ABR deficits and 3 mice that had not undergone ABR testing; 2 of these 3 mice had a negative Preyer reflex. MicroCT scans revealed no gross abnormalities in middle ear anatomy in the Df1/+ mice compared to their WT littermates, and there were no defects in the ossicular chain (Figure S2). However, histological analysis demonstrated a high incidence of OME in the Df1/+ animals (Figure 3E), with frequent signs of inflammation such as effusion, capillary hyperplasia, a thickened tympanic membrane and thickened MEC mucosa (Figure 3F). Affected animals had effusion in one or both ears and the effusion content varied with respect to quantity of infiltrated and inflammatory cells. In some Df1/+ mice with severe OME, the Eustachian tube (ET) was infiltrated by inflammatory cells. Examination of the mucociliary integrity in Df1/+ mice with severe OM revealed increased mucus production within the middle ear adjacent to the orifice where the ET enters the MEC, suggesting increased goblet cell density (Figure 3G compared to C). In Df1/+ mice displaying mild OM, however, this increased mucus secretion was only observed occasionally (data not shown).

Figure 3. Morphological changes in MEC mucosa and epithelium in Df1/+ mice.

(A-C, E-G) Frontal trichrome-stained sections from 11.5-week-old mice showing the middle ear cavity. (D, H) SEM images of middle ear epithelium. (A-D) WT. (E-H) Df1/+ with signs of OM. (A) The middle ear cavity is air-filled in the WT. (B) The mucosa is a thin layer lining the auditory bulla. (C) At the entrance of the Eustachian tube (ET) high levels of alcian blue staining are observed indicating mucin production. Further into the middle ear away from the orifice, staining is less distinct in the WT (arrowheads). (D) A thick lawn of cilia is observed overlying the epithelium near the ET orifice. (E) In Df1/+ mice the middle ear cavity is filled with effusion (arrow). (F) Df1/+ mice show signs of inflammation such as effusion with infiltrated inflammatory cells (asterix), a thickened mucosa (arrow) and hypervascularisation (arrowhead). (G) In addition, increased alcian blue staining is observed within the middle ear at a distance from the ET indicating increased mucin production in Df1/+ mice (compare C and G, arrowheads). (H) Df1/+ mice with OM show reduced numbers of cilia that appear shortened and rarefied. Dorsal is top in A-C, E-G. Scale bar: 500 μm (A, E), 100 μm (B, C, F, G).

Morphological changes in the MEC mucosa in Df1/+ mice with OM

To further investigate OM-associated changes in the pseudostratified mucociliary epithelium lining the MEC, we turned to scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Comparing the density and distribution of cilia next to the opening of the ET, we observed that WT and Df1/+ mice without infiltrated cells in the MEC displayed a thick lawn of evenly distributed cilia adjacent to a border region of unciliated epithelium (Figure 3D). In Df1/+ mice with OME, however, cilia density was reduced and the cilia were rarefied and shortened; in addition, the MEC epithelium was swollen and partly covered in exudate (Figure 3H).

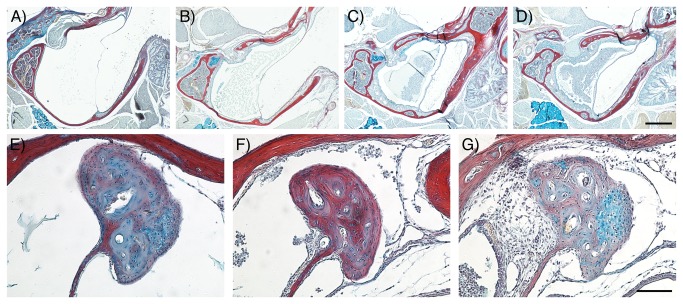

Elevation of ABR thresholds correlates with the severity of OM in Df1/+ mice

To determine whether OM could account for click ABR deficits in Df1/+ mice, we performed histological analysis of the MEC on a set of adult littermates (5 Df1/+ and 1 WT, age 8 weeks) for which click ABRs had been recorded in both ears. The WT mouse and 1 Df1/+ mouse had normal ABR thresholds in both ears; 1 Df1/+ mouse had a slightly elevated ABR threshold in one ear and a normal threshold in the other; 2 Df1/+ mice had a significantly elevated ABR threshold in one ear and a normal or only slightly elevated threshold in the other ear; and 1 Df1/+ mouse had significantly elevated thresholds in both ears. Data from these 6 littermates (12 ears) therefore provided a perfect opportunity to test for a correlation between elevation of click ABR thresholds and signs of OM in Df1/+ animals (Table 1).

Table 1. Correlation between severity of OM and click ABR thresholds in ears from six littermates (5 Df1/+, 1 WT).

|

Signs of OM

|

Click ABR Thresholds

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Severity | Normal | Slightly | Elevated | Severely |

| (<50 dB SPL) | elevated | (60-70 dB SPL) | Elevated | ||

| (50-55 dB SPL) | (>70 dB SPL) | ||||

| Effusion | No effusion | 3+2* | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Serous effusion | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Effusion with <50% infiltrated cells | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Effusion with >50% infiltrated cells | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Mucosa thickening | No thickening (0.077-0.15mm) | 2+2* | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mild thickening (0.151-0.49mm) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Severe thickening (0.491-0.827mm) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

Degree of effusion with infiltrated cells and thickening of the middle ear mucosa directly correlates with elevation of ABR thresholds in ears from the Df1/+ littermates (Spearman's correlation test: rho=0.88, p=0.0007 for severity of effusion; rho=0.75, p=0.013 for severity of mucosa thickening). Ears from the WT littermate, indicated by the asterix (*) , had normal ABR thresholds and no signs of OM.

Two measures of the severity of OM were used: presence of effusion, and increased thickness of the middle ear mucosa. Analysis was performed blind to genotype and was repeated by multiple operators to ensure reliability of classifications.

As shown in Table 1 and Figure 4, Df1/+ ears for which click ABR thresholds were most elevated (>70 dB SPL) had effusion with more than 50% of infiltrated cells within the MEC (Table 1 and Figure 4D). These mice also displayed a severe thickening of the ME mucosa, which could have produced physical obstruction of movement of the ossicles (Figure 4G). In some cases the epithelial thickness was observed to be up to 23 times higher than in WT littermates.

Figure 4. The severity of OM correlates with the degree of hearing loss in Df1/+ mice (see also Table 1).

(A-G) Frontal trichrome-stained sections from adult mice showing the graded severity of effusion in Df1/+ middle ear cavities (A-D) and thickened mucosa around the head of the malleus (E-G). Least severe conditions are displayed on the left hand side panels with increasing severity towards the right hand side panels. (A) No effusion, (B) serous effusion, (C) effusion with <50% infiltrated cells and (D) effusion with >50% infiltrated cells. (E) No thickening, (F) mild thickening and (G) severe thickening of the mucosa around the head of the malleus. Dorsal is top. Scale bar: 500 μm (A-D), 100 μm (E-G).

Df1/+ ears for which ABR recordings had revealed marginally lower thresholds (60-70 dB SPL) displayed effusion with fewer infiltrated cells and a less severe thickening of the mucosa (Table 1 and Figure 4C), indicating a less advanced inflammation. In these animals there was only limited tissue around the ossicles (Figure 4F).

Df1/+ ears with normal or slightly elevated ABR thresholds (40-45 or 50-55 dB SPL) showed either no effusion (Table 1 and Figure 4A) or a serous effusion only (Table 1 and Figure 4B) with no or mild thickening of the mucosa (Figure 4E or F). Thus both the severity of effusion and the severity of mucosa thickening were significantly correlated with elevation of click ABR thresholds across the Df1/+ ears (Table 1; Spearman's correlation test: rho=0.88, p=0.0007 for severity of effusion; rho=0.75, p=0.013 for severity of mucosa thickening). The two ears from the WT animal (2* in Table 1), for which both ABR thresholds were normal, had no effusion (Figure 4A) and normal ME mucosa (Figure 4E).

In addition to these 6 littermates, we also examined 5 more animals which also underwent hearing tests, and we found the same correlation between hearing loss and OM in those additional animals. No evidence of ossicle erosion was observed, but such erosion might only be present in older mice after repeated bouts of OM.

Further observations

Bacteriology

Bacteriological analysis of middle ear swabs obtained from both ears of 4 Df1/+ mice revealed, in 4 out of the 8 ears, the presence of commensal bacteria and opportunistic pathogens that do not normally cause infections in a healthy ear. One mouse had scant growth of Escherichia coli in both ears; another had moderate growth of Lactococcus lactis spp lactis in one ear; a third was found to have scant growth of Pantoea spp in one ear. No fungi or yeast were isolated from any of the samples. These results suggest that OM in Df1/+ mice is unlikely to be caused by unusual susceptibility to a specific pathogen; rather, any bacterial infection of the middle ear in Df1/+ mice is probably a secondary opportunistic process.

Hair cell density in the organ of Corti

To address the possibility that elevated ABR thresholds in Df1/+ mice might arise from sensorineural as well as conductive hearing loss, we examined the sensory epithelium of the inner ear in 6 Df1/+ and 5 WT mice. There was no evidence for significant loss of hair cells sufficient to account for the elevated ABR thresholds in Df1/+ relative to WT mice. Moreover, the density of hair cells in the cochlea appeared normal in both ears of Df1/+ animals with monolateral hearing loss (Figure S3). On the basis of our analysis, we cannot entirely rule out the possibility of subtle inner ear abnormalities in Df1/+ mice, especially given that severe OM can sometimes affect the inner ear. However, we can conclude that the observed click ABR deficit in Df1/+ mice does not arise from hair cell loss.

Discussion

Here we have shown that Df1/+ mice are susceptible to conductive hearing loss and otitis media, which are also common consequences of the human 22q11.2 deletion that the mice were genetically engineered to model. Mouse models of 22q11DS such as the Df1/+ mouse have attracted great interest not only as a tool for investigating the origins of various defects and disabilities associated with this relatively common chromosomal disorder, but also as a means of gaining insight into the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, for which 22q11DS is one of the most significant known risk factors. In the context of this previous research, the present study makes three distinct contributions.

First, the results suggest a resolution to a discrepancy in the literature between previous studies reporting normal hearing in the Df1/+ and Df(16)A/+ mouse models of 22q11DS [23-25] and studies documenting a high incidence of middle ear disease in mice heterozygous for the gene Tbx1 [26], which is included in the Df1/+ and Df(16)A/+ deletion regions. The previous evidence for normal hearing in mouse models of 22q11DS came from supplementary controls in studies of prepulse inhibition (PPI) of acoustic startle. In one study [23], thresholds for acoustic startle were observed to be slightly lower, and startle amplitudes slightly higher, in Df1/+ mice than in their WT littermates; in another study [25], similar results were reported for Df(16)A/+ mice, which have a larger deletion region than Df1/+ mice. Both studies therefore concluded that there was no evidence for reduction in hearing sensitivity in these mice. However, under some circumstances, mice with partial hearing loss can show reduced startle thresholds and elevated startle amplitudes in acoustic startle testing [29], perhaps because central auditory adaptation to the reduction in peripheral input leads to hyperacusis for loud sounds. Better evidence for normal hearing in Df1/+ mice was provided in [24] based on frequency-specific distortion-product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) testing, which is generally an excellent means of detecting peripheral auditory abnormalities including middle ear problems. However, the DPOAE testing in that study was performed on only 6 Df1/+ mice, and apparently only on one ear in each animal. Given the intermittent nature of the ABR deficit and OM observed in the present study (48% of Df1/+ animals, but only 38% of Df1/+ ears tested), it is possible that this sample size was too small. We therefore suggest that previous evidence for normal hearing in Df1/+ and Df(16)A/+ mice was inconclusive, and that all mouse models of 22q11DS involving deletion of Tbx1 may have a high incidence of conductive hearing loss.

The second contribution of the present work is to show that previous reports of abnormal auditory sensorimotor gating in mouse models of 22q11DS need to be re-examined to determine whether abnormalities in auditory processing alone might account for the results. Impaired auditory sensorimotor gating, quantified as a reduction in PPI of acoustic startle, is considered an important endophenotype for risk of schizophrenia. Reduced PPI of acoustic startle has been reported both in human 22q11DS patients [30] and in mouse models of 22q11DS [23-25]. However, as discussed above, the high incidence of conductive hearing loss and otitis media in Df1/+ mice could itself lead to differences between Df1/+ and WT animals in PPI of acoustic startle. Moreover, although we found no abnormalities in hair-cell density that could account for the observed elevation of click ABR thresholds in Df1/+ mice, it is possible that Df1/+ mice have more subtle sensorineural hearing deficits, especially given that Tbx1 is involved in inner ear development [31]. The possibility of such abnormalities could be explored further in the future with tone-evoked ABR measurements or distortion-product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) testing, which are more sensitive assays for frequency-specific hearing loss than click-evoked ABR measurements.

The final contribution of this work is to introduce the Df1/+ mouse as a powerful model system for investigating the pathogenesis of OM in 22q11DS and also more generally. Hearing loss is prevalent among human 22q11DS patients [32], and is almost always related to middle ear infection. In one study, chronic or recurrent otitis media was reported in 52% of 22q11DS patients [18]; in another 88% had otitis media, 53% had conductive hearing loss, and 39% required surgical implantation of ventilation tubes to drain the middle ear [17]. In these patients the causes of the OM have been proposed to be multifactorial involving immune deficiency, palatal abnormalities and Eustachian tube dysfunction [18]. The high incidence of conductive hearing loss and otitis media in Df1/+ mice indicates that these animals can be used to tease apart the causes of frequent OM in 22q11DS patients. Moreover, the prevalence of monolateral ABR deficits and OM in Df1/+ mice creates opportunities for within-animal controls, making the animals a potentially powerful tool for testing hypotheses about the causes of OM. Studies of the mechanism by which genetic predispositions cause OM have been performed in other mouse models, such as the heterozygous Fbxo11 mouse and Eya4 knockout mouse. Fbxo11 is expressed in the lining of the middle ear cavity and has been proposed to affect epithelial inflammatory events in the ear [33]. In contrast, in the Eya4 mouse the morphology of the Eustachian tube and angle of connection to the middle ear have been shown to be defective, potentially causing ear clearance problems [34]. Tbx1 has been shown to be expressed in the endoderm of the developing pharyngeal arches and Tbx1 null mice have a hypoplastic pharynx [35,36]. As the Eustachian tube arises from the endodermally derived first pharyngeal pouch it is therefore tempting to speculate that a subtle early defect in patterning of the endoderm might be responsible for the high incidence of OM in Df1/+ and Tbx1 heterozygous mice. Our ongoing efforts to pinpoint the causes of otitis media in Df1/+ mice are therefore focusing on the possibility of abnormalities in the morphology of the Eustachian tube and/or the other endodermally derived tissues of the middle ear [37].

In conclusion: Df1/+ mice, like human 22q11DS patients, are susceptible to otitis media and conductive hearing loss, which affect nearly half the animals but often in only one ear. The findings suggest that abnormal auditory sensorimotor gating previously reported in mouse models of 22q11DS could arise from abnormalities in auditory processing. More broadly, the results indicate that Df1/+ mice are an important model system for investigating the causes of OM in both 22q11DS patients and the many children worldwide who suffer from chronic middle ear infections.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All in vivo experiments were conducted in accordance with the United Kingdom's Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986, under a project licence approved by the UK Home Office.

Animals

The Df1/+ mouse line had been maintained on a C57BL/6 background for a minimum of 10 generations prior to the analyses. The Df1 deletion itself was engineered on a 129S5 SvEvBrd genetic background [21].

Hearing tests

Auditory brainstem response measurement

ABR testing was performed in a sound isolation booth (Industrial Acoustics Company, Inc.). Mice were anaesthetised with ketamine and medetomidine. Body temperature was maintained at 37-38°C using a homeothermic blanket (Harvard Apparatus). Subdermal needle electrodes (Rochester Medical) were inserted under the skin with positive electrode at the vertex, negative electrode near the ear being tested, and ground electrode near the opposite ear (which was blocked with a sound-attenuating earplug). For most animals, ABR recordings were obtained from both the left and right ears in turn, with an earplug in the ear opposite to that under test (to ensure monaural stimulus presentation).

Auditory stimuli were presented via a free-field speaker (FF1) from Tucker-Davis Technologies (TDT). Speaker output was calibrated before each set of experiments using a Bruel & Kjaer ¼ inch microphone (4939), placed at the location of the ear to be tested. Stimulus generation and data acquisition were accomplished using hardware from TDT (RX6 and RX5 signal processors, RA4LI and RA16SD signal amplifiers, PA5 attenuator, and SA1 speaker amplifier), a custom low-pass filter designed to remove attenuation switching transients, and software from TDT (Brainware) and Mathworks (Matlab).

Stimuli were 50 μs monophasic clicks ranging in sound level from 0 to 90 dB SPL, presented at a rate of 20 clicks/sec. ABR recordings typically included 500 repeats of click stimuli presented over a 20-80 dB SPL range at 20 dB intensity increments, followed by 1000 repeats of click stimuli presented over a smaller intensity range at 5 dB intensity increments. The threshold was defined to be the lowest click intensity evoking a clear and characteristic deflection of the ABR wave that was at least as large as the time-dependent standard error in the mean wave at that sound intensity.

Preyer reflex assessment

A few of the mice used for studies of middle ear anatomy and histology did not undergo ABR measurement due to time constraints, and instead were tested for a Preyer reflex. The Preyer reflex is a flick of the pinnae evoked by a transient loud sound. To present such sounds, we used a custom-built click box (MRC Institute of Hearing Research, Nottingham, UK) emitting a brief 18.5 kHz tone burst with intensity 95-105 dB SPL at the distances typically used for testing. Since the Preyer reflex is somewhat unreliable even in animals with normal hearing, we judged the Preyer reflex to be negative only if an animal showed no Preyer reflex across several presentations of the sound.

Middle ear analyses

Histology

Mouse heads were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C and then decalcified in EDTA Solution (67.5% EDTA, 7.5% PBS and 25% PFA (4%)). The tissue was then dehydrated through a methanol series and isopropanol and cleared in tetrahydronaphthalene before embedding in paraffin wax. The 9 μm frontal sections were mounted on Superfrost Plus Slides, dewaxed in Histoclear, rehydrated through IMS, stained with 1% Alcian blue in 3% acetic acid pH2.5, Ehrlich’s haematoxylin, and 0.5% Sirius Red in saturated picric acid, and then mounted in DPX. Slides were imaged on a Nikon Digital Sight Camera. Measurement of mucosa thickness was performed using Image J software.

Scanning electron microscopy

The temporal bones of adult mice were dissected and the middle ear mucosa revealed by removing the outer ear, eardrum, tympanic ring and the malleus and incus. These were then fixed in 2.5% gluteraldehyde in 0.15M cacodylate buffer (pH7.2) overnight at 4°C, and washed and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. Next specimens were dehydrated through an ethanol series and dried using a Polaron E3000 critical point dryer. After mounting and coating with gold (Emitech K550X sputter coater), the surface of the mucosa was examined and images recorded using a Hitachi S-3500N scanning electron microscope (SEM) operated at 10kV in high vacuum mode.

MicroCT reconstruction

Micro computerized tomography (microCT) was used for the three-dimensional analysis of Df1/+ and WT middle ear morphology.

Inner ear analysis

Cochleae were fixed in 4% PFA in PBS for 2 hrs, then decalcified in 4% EDTA in PBS at pH7.4 for 48 hrs at 4°C. The organ of Corti was extracted in half-turn segments, permeabilised in 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and incubated with fluorescently conjugated phalloidin at 1 μg/ml for 2 hrs. Phalloidin labels filamentous actin and therefore delineates both hair cell stereocilia and intercellular junctions at the luminal surface of the organ of Corti. Segments were mounted on slides using an anti-photobleaching agent (Vectashield) that also contained DAPI (VectaLabs) to label cell nuclei. Slides were then examined and images taken with a confocal microscope (Zeiss) and viewed for analysis through LSM browser (Zeiss).

Supporting Information

Example click ABR waveforms from a WT mouse (A) and a Df1/+ littermate (B), both male and 29 weeks old. Left plots show ABR waveforms evoked by clicks at 20, 40, 60 and 80 dB SPL, averaged over 500 trials for each stimulus. Right plots show ABR waveforms evoked by clicks presented over a smaller intensity range and at finer intensity resolution, averaged over 1000 trials per stimulus. Grey shading around black lines indicates standard error of the mean across trials. Threshold was judged to be 30 dB SPL for the WT mouse (A), and 65 dB SPL for the Df1/+ animal (B).

(TIF)

Middle ear structure in adult WT and Df1/+ mice. MicroCT reconstruction of the bony auditory bulla surrounding the middle ear cavity, with ossicles shown in pseudocolor. No differences in morphology of the middle ear and the ossicular chain were observed between (A) WT and (B) Df1/+ mice. Scale bar: 1mm.

(TIF)

Whole-mount organ of Corti segments taken from the basal turns of the left (A) and right (B) cochleae in a male Df1/+ mouse (age 24 weeks) with pronounced monolateral hearing loss. ABR thresholds measured in vivo were 65 dB SPL for the left ear and 35 dB SPL for the right ear. In both ears, the sensory epithelium appears relatively normal for an animal of this age, with only the occasional hair cell missing. Red, phalloidin stain (highlighting filamentous actin in hair cells); blue, DAPI (highlighting cell nuclei). Scale bars: 20 μm.

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Alice Warley and Dr Gema Vizcay-Barrena (Centre for Ultrastructural Imaging, King's College London) for help with the SEM work; Dr Jean-Philippe Mocho (Royal Veterinary College) for assistance with bacteriological analysis; and Ms Jenifer Suntharalingham for help with genotyping.

Funding Statement

Work by JFL and FAZ was supported by the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, Deafness Research UK, and the UCL MSc Neuroscience programme. AST, RRT, and AF are funded by the Medical Research Council and JCF is funded by Action on Hearing Loss. PJS and SI are supported by the British Heart Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Scambler PJ (2000) The 22q11 deletion syndromes. Hum Mol Genet 9: 2421-2426. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.16.2421. PubMed: 11005797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scambler PJ (2010) 22q11 deletion syndrome: a role for TBX1 in pharyngeal and cardiovascular development. Pediatr Cardiol 31: 378-390. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9613-0. PubMed: 20054531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paylor R, Lindsay E (2006) Mouse models of 22q11 deletion syndrome. Biol Psychiatry 59: 1172-1179. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.018. PubMed: 16616724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lindsay EA, Baldini A (1998) Congenital heart defects and 22q11 deletions: which genes count? Mol Med Today 4: 350-357. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(98)01302-1. PubMed: 9755454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ryan AK, Goodship JA, Wilson DI, Philip N, Levy A et al. (1997) Spectrum of clinical features associated with interstitial chromosome 22q11 deletions: a European collaborative study. J Med Genet 34: 798-804. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.10.798. PubMed: 9350810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Epstein JA (2001) Developing models of DiGeorge syndrome. Trends Genet 17: S13-S17. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02164-8. PubMed: 11585671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gerdes M, Solot C, Wang PP, Moss E, LaRossa D et al. (1999) Cognitive and behavior profile of preschool children with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion. Am J Med Genet 85: 127-133. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19990716)85:2. PubMed: 10406665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murphy KC (2002) Schizophrenia and velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Lancet 359: 426-430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07604-3. PubMed: 11844533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reyes MRT, LeBlanc EM, Bassila MK (1999) Hearing loss and otitis media in velo-cardio-facial syndrome. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 47: 227-233. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(98)00180-3. PubMed: 10321777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Paradise JL, Rockette HE, Colborn DK, Bernard BS, Smith CG et al. (1997) Otitis media in 2253 Pittsburgh-area infants: prevalence and risk factors during the first two years of life. Pediatrics 99: 318-333. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.3.318. PubMed: 9041282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Richter CA, Amin S, Linden J, Dixon J, Dixon MJ, Tucker AS (2010) Defects in middle ear cavitation cause conductive hearing loss in the Tcof1 mutant mouse. Hum Mol Genet 19: 1551-1560. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq028. PubMed: 20106873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lannigan FJ, O'Higgins P, McPhie P (1993) The cellular mechanism of ossicular erosion in chronic suppurative otitis media. J Laryngol Otol 107: 12-16. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100122005. PubMed: 8445302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Browning GG, Rovers MM, Williamson I, Lous J, Burton MJ (2010) Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Clin Otolaryngol 35: 490-491. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2010.02230.x. PubMed: 20927726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Uhari M, Mäntysaari K, Niemelä M (1996) Meta-analytic review of the risk factors for acute otitis media. Clin Infect Dis 22: 1079-1083. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1079. PubMed: 8783714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casselbrant ML, Mandel EM, Fall PA, Rockette HE, Kurs-Lasky M et al. (1999) The heritability of otitis media: a twin and triplet study. JAMA 282: 2125-2130. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2125. PubMed: 10591333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lazaridis E, Saunders JC (2008) Can you hear me now? A genetic model of otitis media with effusion. J Clin Invest 118: 471–474. PubMed: 18219392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ford LC, Sulprizio SL, Rasgon BM (2000) Otolaryngological manifestations of velocardiofacial syndrome: a retrospective review of 35 patients. Laryngoscope 110: 362-367. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200003000-00006. PubMed: 10718420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dyce O, McDonald-McGinn D, Kirschner RE, Zackai E, Young K, Jacobs IN (2002) Otolaryngologic manifestations of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 128: 1408–1412. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.12.1408. PubMed: 12479730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galili N, Baldwin HS, Lund J, Reeves R, Gong W et al. (1997) A region of mouse chromosome 16 is syntenic to the DiGeorge, velocardiofacial syndrome minimal critical region. Genome Res 7: 17-26. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.1.17. PubMed: 9037598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sutherland HF, Kim UJ, Scambler PJ (1998) Cloning and comparative mapping of the DiGeorge syndrome critical region in the mouse. Genomics 52: 37-43. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5414. PubMed: 9740669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lindsay EA, Botta A, Jurecic V, Carattini-Rivera S, Cheah YC et al. (1999) Congenital heart disease in mice deficient for the DiGeorge syndrome region. Nature 401: 379-383. doi: 10.1038/43900. PubMed: 10517636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taddei I, Morishima M, Huynh T, Lindsay EA (2001) Genetic factors are major determinants of phenotypic variability in a mouse model of the DiGeorge/del22q11 syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 11428-11431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201127298. PubMed: 11562466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Paylor R, McIlwain KL, McAninch R, Nellis A, Yuva-Paylor LA et al. (2001) Mice deleted for the DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome region show abnormal sensorimotor gating and learning and memory impairments. Hum Mol Genet 10: 2645-2650. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.23.2645. PubMed: 11726551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Paylor R, Glaser B, Mupo A, Ataliotis P, Spencer C et al. (2006) Tbx1 haploinsufficiency is linked to behavioral disorders in mice and humans: implications for 22q11 deletion syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 7729-7734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600206103. PubMed: 16684884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stark KL, Xu B, Bagchi A, Lai WS, Liu H et al. (2008) Altered brain microRNA biogenesis contributes to phenotypic deficits in a 22q11-deletion mouse model. Nat Genet 40: 751-760. doi: 10.1038/ng.138. PubMed: 18469815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liao J, Kochilas L, Nowotschin S, Arnold JS, Aggarwal VS et al. (2004) Full spectrum of malformations in velo-cardio-facial syndrome/DiGeorge syndrome mouse models by altering Tbx1 dosage. Hum Mol Genet 13: 1577-1585. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh176. PubMed: 15190012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parham K (1997) Distortion product otoacoustic emissions in the C57BL/6J mouse model of age-related hearing loss. Hear Res 112: 216-234. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(97)00124-X. PubMed: 9367243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zheng QY, Johnson KR, Erway LC (1999) Assessment of hearing in 80 inbred strains of mice by ABR threshold analyses. Hear Res 130: 94-107. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00003-9. PubMed: 10320101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ison JR, Allen PD, O'Neill WE (2007) Age-related hearing loss in C57BL/6J mice has both frequency-specific and non-frequency-specific components that produce a hyperacusis-like exaggeration of the acoustic startle reflex. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8: 539-550. doi: 10.1007/s10162-007-0098-3. PubMed: 17952509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sobin C, Kiley-Brabeck K, Karayiorgou M (2005) Lower prepulse inhibition in children with the 22q11 deletion syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 162: 1090–1099. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1090. PubMed: 15930057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vitelli F, Viola A, Morishima M, Pramparo T, Baldini A, Lindsay E (2003) TBX1 is required for inner ear morphogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 12: 2041-2048. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg216. PubMed: 12913075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Digilio MC, Pacifico C, Tieri L, Marino B, Giannotti A, Dallapiccola B (1999) Audiological findings in patients with microdeletion 22q11 (di George/velocardiofacial syndrome). Br J Audiol 33: 329-333. doi: 10.3109/03005369909090116. PubMed: 10890147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hardisty-Hughes RE, Tateossian H, Morse SA, Romero MR, Middleton A et al. (2006) A mutation in the F-box gene, Fbxo11, causes otitis media in the Jeff mouse. Hum Mol Genet 15: 3273-3279. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl403. PubMed: 17035249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Depreux FFS, Darrow K, Conner DA, Eavey RD, Liberman MC et al. (2008) Eya4-deficient mice are a model for heritable otitis media. J Clin Invest 118: 651-658. PubMed: 18219393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jerome LA, Papaioannou VE (2001) DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for the T-box gene, Tbx1. Nat Genet 27: 286-291. doi: 10.1038/85845. PubMed: 11242110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vitelli F, Lindsay EA, Baldini A (2002) Genetic dissection of the DiGeorge syndrome phenotype. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 67: 327-332. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2002.67.327. PubMed: 12858556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thompson H, Tucker AS (2013) Dual origin of the epithelium of the mammalian middle ear. Science 339: 1453-1456. doi: 10.1126/science.1232862. PubMed: 23520114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Example click ABR waveforms from a WT mouse (A) and a Df1/+ littermate (B), both male and 29 weeks old. Left plots show ABR waveforms evoked by clicks at 20, 40, 60 and 80 dB SPL, averaged over 500 trials for each stimulus. Right plots show ABR waveforms evoked by clicks presented over a smaller intensity range and at finer intensity resolution, averaged over 1000 trials per stimulus. Grey shading around black lines indicates standard error of the mean across trials. Threshold was judged to be 30 dB SPL for the WT mouse (A), and 65 dB SPL for the Df1/+ animal (B).

(TIF)

Middle ear structure in adult WT and Df1/+ mice. MicroCT reconstruction of the bony auditory bulla surrounding the middle ear cavity, with ossicles shown in pseudocolor. No differences in morphology of the middle ear and the ossicular chain were observed between (A) WT and (B) Df1/+ mice. Scale bar: 1mm.

(TIF)

Whole-mount organ of Corti segments taken from the basal turns of the left (A) and right (B) cochleae in a male Df1/+ mouse (age 24 weeks) with pronounced monolateral hearing loss. ABR thresholds measured in vivo were 65 dB SPL for the left ear and 35 dB SPL for the right ear. In both ears, the sensory epithelium appears relatively normal for an animal of this age, with only the occasional hair cell missing. Red, phalloidin stain (highlighting filamentous actin in hair cells); blue, DAPI (highlighting cell nuclei). Scale bars: 20 μm.

(TIF)