Abstract

This study examined participants’ perceptions of how their involvement in a well-established weight loss and diabetes prevention program influenced their social support persons (SSPs). Utilizing a mixed-methods approach, participants were surveyed to determine their perceived influence on SSPs. Compared to controls, intervention participants reported that SSPs’ lifestyle changes were more positively influenced by their study participation, and their amount of weight loss was related to favorability of perceived changes in SSPs’ eating habits. Themes of lifestyle changes, knowledge dissemination, and motivation emerged from responses. Future lifestyle change interventions could potentially capitalize on program participants’ influence on their social support networks.

Keywords: diabetes, obesity, social support

In recent decades, prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity have increased at alarming rates in adults and children,1-3 accompanied by mounting health and financial burdens.4 Annual medical expenditures associated with T2DM and obesity care cost $174 billion5 and $147 billion, respectively.6 Trends indicate 65 million new cases of obesity and up to 8.5 million of T2DM by the year 2030,7 and projected costs of this rise are estimated to approach $957 billion.8 It is unlikely that these trends will be reversed without effective and pervasive prevention and treatment options.

As the spread of obesity has been linked within social circles (ie, friends, siblings, and spouses),9 it is logical to assume that healthy behavior change may follow a similar pattern.10 For individuals engaged in behaviorally based obesity and T2DM treatment, their participation in such programs may be influential on the health of members of their social networks. Due to these social influences, treatment programs demonstrating effectiveness in reducing obesity and T2DM could potentially affect a greater number of people than just those who participate directly. Future research may benefit from an investigation of social support networks and the role they play in healthy weight-related behaviors.

Evidence suggests that obesity not only spreads through social networks of family and friends, but also tends to cluster within them.9-11 Christakis and Fowler9 found that the likelihood of an adult becoming obese increased by 57%, 40%, and 37%, respectively, if a friend, sibling, or spouse became obese. Similarly, overweight and obese young adults were more likely than their normal weight peers to have romantic partners and friends who were also overweight,10 and also reported to having more overweight family members. Network-based interaction models have simulated the transmission of obesity throughout social systems, postulating effective weight management strategies to target these systems.11 Simulations show that clusters of overweight and obese people are becoming increasingly more overweight due to social forces within their groups.11 Fortunately for those attempting to lose weight, possessing more social contacts also attempting weight loss has been associated with greater intention to lose weight.10 Thus, traditional weight management programs focusing solely on individuals may be less effective, as they do not address larger social contexts in which individuals operate.11

Although familial and social contacts clearly mediate the weight loss process, there is ambiguity over which, and to what extent, these contacts are involved.12-16 Meta-analyses demonstrate that behavioral weight loss programs incorporating varying degrees of social support are superior to programs that do not.13,14 In a study of the type of social support maintained during a weight loss program,12 women were more likely to lose weight if they reported frequent family and friend support, and least likely to lose weight if they had received no family support. Women who had never before experienced friend support were surprisingly the most likely to lose weight, perhaps because participation in the program provided a new-found source of social support.12

To broaden the perspective, some studies have considered weight loss changes in the familial and social contacts of program participants.15, 16 Gorin et al found that it was not the number of social contacts participants enlisted with them in their weight loss program, but rather the weight loss success of the enlisted contacts that was associated with improved outcomes.16 Untreated spouses have also been shown to reap health benefits from weight loss programs as a result of their spouse's direct participation, including weight loss, reduced energy intake, and reduced percent energy intake from fat.15 This “ripple effect” implies that lifestyle changes made by individuals can radiate through their social systems.15 Novel findings such as these suggest social networks of friends and families may be key leverage points for targeting weight and health. For perhaps the greatest impact on obesity and T2DM prevalence, existing evidence-based interventions should be expanded to incorporate familial and social contacts.

The present study examined participants in a well-established weight loss and diabetes prevention program and participants’ perceived influence over the health behaviors of individuals in their social networks, referred to here as social support persons (SSPs). Participants were enrolled in the Healthy-Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes (HELP PD) study, a community translation of the Diabetes Prevention Program designed to reduce the incidence of T2DM in a diverse population of prediabetic adults through weight loss and physical activity.17 HELP PD effectively incorporated group-based lifestyle weight loss (LWL) interventions in partnership with an existing community-based diabetes education program (DEP), led by community health workers (CHWs).18 The goals of this study were to: investigate whether participants in an intensive lifestyle intervention differed in their perceived impact on the lifestyle behaviors of their SSPs; determine if perceptions were related to participant weight loss; and qualitatively identify emergent themes from those perceptions. Relative to controls, we hypothesized that lifestyle intervention participants, particularly those with the greatest weight loss at 6 months, would report greater perceived change (PC) in the weight-related habits of their identified SSPs. Based on qualitative records, we hypothesized that participants would perceive their involvement in HELP PD to be influential over the health behaviors of their SSPs.

METHODS

HELP-PD

Design, study population, and measures

The design and methods of the HELP PD study have been thoroughly described elsewhere.18-20 The HELP PD population included a representative community sample of individuals at risk for developing T2DM.20 Eligible participants had to have evidence of prediabetes (fasting glucose between 95 and 125 mg/dL) on a minimum of 2 occasions and a body mass index (BMI) between 25.0 and 39.9 kg/m.2,18,20

Participants (n 301) were recruited through mass mailings within target ZIP codes.18,20 The screening process for the study was tiered, involving an initial telephone screening for prospective participants, followed by group information sessions for those meeting eligibility criteria.20 In the final step of the screening process, potential participants were seen in the General Clinical Research Center of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center for fasting blood work and anthropometry. Candidates were screened for comorbidi-ties that could potentially hinder participation or be unsafe to their health.18 Following consent, participants were randomized into either an intensive lifestyle intervention group or an enhanced usual care comparison group.18,20 Data were collected from all participants in 6-month intervals for 24 months,18 and included fasting blood glucose, insulin, lipids, blood, pressure, anthropometry, and other nutrition and behavior questionnaires.18

Implementation and intervention

Lifestyle weight loss interventions were conducted at community-based sites under the guidance of a local DEP and CHWs.18 Although the study team handled all administrative issues, intervention management as well as training of the CHWs was conducted by registered dietitians employed by the DEP. Community health workers were recruited through the DEP, as all CHWs were type 2 diabetics with well-controlled HbA1c and histories of healthy lifestyles.18 Community health workers were trained via a 36-hour program conducted over the course of 6-9 weeks focused on the type of instruction and observation they would be expected to provide to HELP PD participants.18 Responsibilities of the CHWs included conducting the intervention group sessions and managing participants.18

The LWL intervention was designed to produce 5-7% weight loss in participants by encouraging reduced caloric intake and increased physical activity,18 followed by maintenance of weight loss over the next 18 months. Intervention groups consisted of 8-12 participants led by CHWs and supervised by 2 dietitians. During the initial 6-month intensive period each group met weekly to discuss healthy eating, exercise, motivation, and problem solving, followed by monthly meetings for the remaining 18-month maintenance phase.

Those randomized to the usual care comparison group were intended to receive enhanced care more than usually provided to prediabetic patients.18 These participants received monthly newsletters and 2 nutrition counseling sessions with a dietitian not affiliated with the LWL intervention.18,20

HELP PD analysis

Analyses of HELP PD's 1-year results regarding participants’ blood glucose, insulin resistance, and anthropometric measures are presented in detail elsewhere.18 In brief, the effect of the LWL intervention on the intervention and usual care comparison groups was compared at 6- and 12-month intervals using general linear models for repeated measures. Intervention effect was examined using least square means of the estimated main effect of the intervention and a 5% two-sided level of significance standard was used to make inferences for comparisons.

SSP questionnaire

A subset of HELP PD participants in each treatment group were surveyed regarding the perceived effect of their participation on the behaviors and weight changes of individuals in their own social support systems. Specifically, participants were asked to identify up to 5 SSPs, or individuals to whom they relied on for support during their participation in HELP PD, including spouses, children, friends, etc. Questionnaires were administered to all participants via interviews conducted by a first year medical student who was trained by study investigators and staff on proper interview techniques and data-collection procedures. These interviews were part of an institutionally sponsored summer program designed to provide experiential learning opportunities in human subject research for medical students. Interviews were conducted with participants at scheduled data collection visits during the summer of 2009. To protect confidentiality, interviews were conducted in a private examination room. Prior to data collection, all study procedures were approved by the Wake Forest Baptist Health Institutional Review Board and a separate consent was collected for these interviews. Participation in these interviews was voluntary and was not required for participation in the HELP PD program.

Questionnaires were designed to elicit quantitative and qualitative data allowing unique and comprehensive interpretation of participants’ responses. Quantitative data was gathered from the first part of the survey, which consisted of multiple-choice questions that were then coded numerically. Qualitative data were gathered from the second part of the survey, which consisted of open-ended questions. To ensure accurate recording of the qualitative information, participants’ responses were transcribed verbatim by the research team member administering the survey.

Quantitative methodology

Questionnaires included a total of 15 questions pertaining to each SSP identified by the participant. Questions focused on the nature of the participants’ relationship with each SSP, the participants’ observation of SSPs’ lifestyle changes, the participants’ perceived effect of their participation in HELP PD on SSPs’ lifestyle changes, and the extent of SSPs’ weight change.

Outcome measures were calculated for each group (intervention or control), and included participant's PC in SSPs’ habits, favorability of those changes (FC), and the relationship of PC and FC to the intervention for diet and exercise behaviors (Change Dependent on the Participant). Perceived change for weight (gain or loss) and perceived weight change (PWC; a range estimate of weight gained or lost) were also recorded. Perceived change for diet and exercise were calculated by dividing the number of participants who reported observed changes in SSPs’ eating or activity habits since enrollment, by the total number of respondents. FC for diet and exercise were calculated by dividing the number of participants who reported their SSPs’ were eating a little or a lot healthier than before/exercising a little or a lot more than before, by the total number of respondents. Change Dependent on the Participant was calculated by dividing the number of participants who reported having a slightly positive effect or a very positive effect on the SSP's eating/exercise habits, by the total number of respondents who reported an observed change in eating/exercise habits. Perceived change for weight was calculated by dividing the number of participants reporting a change in SSPs’ weight (loss or gain) since the participant's enrollment, by the total number of respondents. Because SSPs’ PWC was estimated within a range, overall PWC was calculated by taking the mean of all participant responses. Weight losses were considered negative, weight gains as positive, and no weight change was analyzed as 0. These values were then divided by the total number of respondents in each group, and reported as a mean with standard error.

Quantitative analysis

To investigate PCs in eating and exercise habits of SSPs, means and frequencies of the outcomes measures were used to describe the population. Because participants reported multiple SSPs and these data were likely to be correlated, a modeling structure was used. Generalized estimating equation was used to model the effect of the intervention on binary outcomes of interest. For PWC a mixed model was used, accounting for correlated data. The impact of 6-month weight change was modeled similarly, restricted to those randomized to the intervention, and adjusted for baseline participant characteristics (BMI, age, gender, and race/ethnicity).

Qualitative methodology

Questionnaires also included 5 open-ended questions (Table 1) regarding participants’ PCs in their SSPs’ lifestyle habits (eating and exercise), the participants’ perceived contribution to these changes, as well as all other perceived influences on their SSPs’ lifestyle beyond eating and exercise.

Table 1.

Participant Survey Qualitative Questions

| Question | |

|---|---|

| Eating habits | If there was a change in your significant SSP's eating habits, in what ways did it change? |

| If you think you had an effect, please briefly explain how you contributed to that effect. | |

| Physical activity/exercise habits | If there was a change in your SSP's physical activity/exercise habits, in what ways did it change? |

| If you think you had an effect please briefly explain how you contributed to that effect. | |

| Lifestyle impact | If you feel you impacted your SPP's lifestyle in any other way, in what ways do you think you had an impact? |

Qualitative analysis

Grounded theory guided qualitative analysis, as this inductive approach allows themes to emerge from a body of data without prior knowledge of how the data may be conceptually organized.21 Study staff (J.B.) first reviewed raw data to gain a sense of emergent ideas, and codes were then created to reflect participants’ perceptions within each question. Each code was defined and conceptually differentiated in order to facilitate the coding process and prevent development of analogous codes. The frequency of codes was documented to indicate which ideas were most prominent. Codes were then merged into sub-themes that bridged ideas across questions, and were grouped into major themes to create a broad conceptual organization of responses and highlight the most salient ideas. Throughout this process, subthemes and themes were continually revised with the help of additional study staff (M.B.I., J.A.S.) in order to consider multiple perspectives for data organization and thematic analysis. This coding process was performed for both the intervention and usual care groups, allowing for qualitative comparisons between them.

RESULTS

Help PD

One-year results of the HELP PD study have been described previously,18 but are summarized briefly here. Compared to controls, LWL intervention participants demonstrated significant increases in percent of weight lost, as well as decreases in absolute weight, BMI, waist circumference, fasting glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance. These results are representative of the 6- and 12-month follow-up periods.

SSP questionnaire

Quantitative results

Thirty-six intervention participants and 35 usual care participants completed the survey (Table 2). No statistically significant differences were found between groups, nor were there differences in characteristics between questionnaire respondents and those that only participated in HELP PD.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Intervention (Subgroup in this Substudy [n = 36]) | Control (Subgroup in this Substudy [n = 37]) | Total HELP PD Population (n = 301) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: mean (SD) | 59.1 (9.5) | 59.5 (8.6) | 57.9 (9.5) |

| Gender: n (%) | |||

| Male | 14 (39%) | 18 (49%) | 128 (43%) |

| Female | 22 (61%) | 19 (51%) | 173 (58%) |

| Ethnicity: n (%) | |||

| White | 25 (69%) | 28 (76%) | 220 (73%) |

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 11 (31%) | 7 (19%) | 74 (25%) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 2 (5%) | 4 (1%) |

| Other/missing | 0 | 0 | 3 (1%) |

| Educational status: n (%) | |||

| Less than high school | 2 (6%) | 0 | 8 (3%) |

| High school | 8 (22%) | 4 (11%) | 52 (17%) |

| Associate degree | 12 (33%) | 13 (35%) | 97 (32%) |

| Bachelor's degree or above | 14 (39%) | 20 (54%) | 143 (48%) |

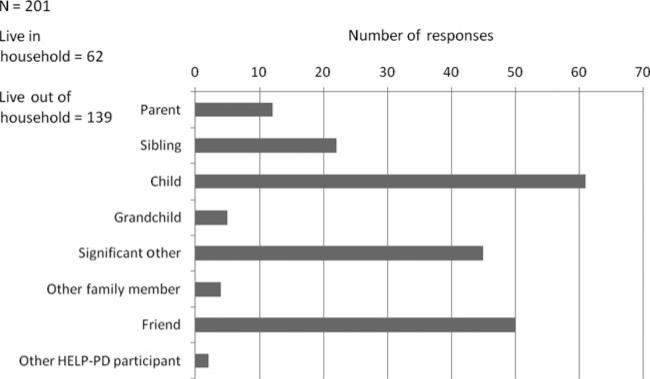

Figure 1 displays the participants’ relationship to their identified SSPs. A total of 201 SSPs were listed by both groups, with the following designations: “Parent” included mothers, fathers, and parents-in-law; “Sibling” included brothers, sisters, and siblings-in-law; “Child” included sons, daughters, children-inlaw, and children's significant others; “Significant Other” included husbands, wives, girlfriends, and fiancés; “Other Family Member” included aunts and nieces; “Friend” included coworkers, neighbors, pastors, and other nonspecified friends; “Other HELP PD participant” included other HELP PD group members as well as leaders. The most commonly reported categories were that of “Child” and “Friend” with 61 and 50 SSPs, respectively. Within these categories, “daughter” and “friend” were the most commonly reported SSP with 34 and 41, respectively. Thirty-one percent (62 of 201) of the SSPs were reported to cohabitate with the participant.

Figure 1.

Participants’ social support persons (SSPs).

Table 3 displays participants’ perceived effect on their SSPs. Perceived change and FC were modestly, yet not significantly, greater for both diet and exercise in intervention participants. There was a statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of who and to what they attributed their SSP's change in diet and exercise (P = .0112 and P 0.0157, respectively). A higher percentage of=Change Dependent on the Participant was found for intervention participants compared to controls.

Table 3.

Participants’ Effects on Their SSPs

| Diet |

Exercise |

Weight |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Change (PC) | Favorable Change (FC) | Change Dependent on the Participant | Perceived Change (PC) | Favorable Change (FC) | Change Dependent on the Participant | Perceived Change (PC) | Perceived Weight Change (PWC) | |

| Intervention (n= 110) | 60 (55%) | 57 (52%) | 53 (88%) | 50 (46%) | 49 (45%) | 40 (80%) | 56 (51%) | –5.0 (13.3) |

| Controls (n = 92) | 45 (49%) | 43 (47%) | 29 (64%) | 30 (33%) | 30 (33%) | 14 (47%) | 46 (51%) | –7.2 (18.0) |

| P values | NS | NS | 0.0112 | NS | NS | 0.0157 | NS | NS |

Abbreviation: NS = not statistically significant.

Participants’ mean 6-month weight loss and change in BMI were also compared between the intervention and usual care groups. Intervention participants demonstrated a mean weight loss of 7.7 (±6) pounds and lowered BMI by 2.6 (±2.8 kg/m2), compared to a loss of 0.4 (±2.1) pounds in the usual care participants, and a mean BMI reduction of 0.2 (±1.0 kg/m2). Associations between intervention participants’ own 6-month weight loss and the PC in SSPs are shown in Table 4. More favorable change in SSPs’ eating habits was related to greater participant weight loss at 6 months, though no significant associations were found between participant weight loss at 6 months and FC in SSPs’ activity habits or PC in SSPs’ weight loss.

Table 4.

Association of Participant 6-Month Weight Loss to Outcome (Perceived Change in SSP; Intervention Group Only)

| Outcomes | Participant Weight Change at 6-Months Mean (SD) | Unadjusted P Value | *Adjusted P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived change in SSP's eating habits | 0.0220 | 0.0347 | |

| No | –6.0 (5.4) | ||

| Yes | –8.2 (5.7) | ||

| Nature of change | 0.0287 | 0.0392 | |

| No change, eats a little, or a lot less healthily than before | –5.9 (5.5) | ||

| Eats a little or a lot more healthily than before | –8.4 (5.5) | ||

| **Perceived impact on SSP's eating habits | 0.2821 | NS | |

| No effect, slightly or very negative effect | –5.8 (6.5) | ||

| Slightly or very positive effect | –8.5 (5.5) | ||

| Perceived change in SSP's activity habits | 0.2886 | NS | |

| No | –6.6 (5.9) | ||

| Yes | –7.9 (5.3) | ||

| Nature of change | 0.2087 | NS | |

| No change, exercises a little or a lot less than before | –6.6 (5.9) | ||

| Exercises a little or a lot more than before | –8.0 (5.3) | ||

| **Perceived impact on SSP's exercise habits | 0.3896 | NS | |

| No effect, slightly or very negative effect | –6.1 (6.3) | ||

| Slightly or very positive effect | –8.3 (5.0) | ||

| Perceived change in SSP's weight | 0.4535 | NS | |

| No | –7.6 (5.6) | ||

| Yes | –6.8 (5.6) |

Note: Both unadjusted and adjusted models account for the clustering of the HELP participant.

Adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, baseline BMI.

Restricted to those that had a change in eating habits/exercise habits.

Abbreviation: NS = not statistically significant.

Qualitative results

Three broad themes emerged from the participants’ questionnaire responses in both groups, reflecting the most commonly perceived effects on SSPs: descriptions of SSP lifestyle changes, methods of knowledge dissemination, and forms of SSPs’ motivation. Themes, subthemes, and representative quotations are displayed in Table 5 and are described in the following sections.

Table 5.

Themes and Quotes

| Themes | Subthemes | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle changes | Eating behaviors | “She is more conscious of her portion sizes. She eats on a more scheduled basis instead of snacking all the time. She is also more conscious of calorie intake.” |

| “He has been very willing to change his old recipes to fit my new healthy eating habits.” | ||

| Exercise behaviors | “He committed to playing golf twice a week and he also gardens a lot more now.” | |

| “He started going after I joined the YMCA. He liked working out and never stopped after he started.” | ||

| Emotional changes | “The study has brought myself and her closer together because I have been able to drop some of my bad habits and become more balanced.” | |

| “She is much happier now and takes much more pride in her physical appearance.” | ||

| Disease prevention | “[She] and her sisters are now able to talk to each other about health, diabetes and their family history of certain diseases. | |

| “The change he has made has helped to get his diabetes under control. He is now taking one less shot and one less pill.” | ||

| Knowledge dissemination | Discussions | “I have talked to her about limiting the amount of unhealthy foods. I also talked to her about staying consistent in her eating habits.” |

| “I let her know the benefits of exercise and talked to her about how good exercise made her feel.” | ||

| Nutrition instruction & advice | “I taught her to eat smaller portion by using smaller plates. I also taught her to count calories and read labels.” | |

| “I have been giving her tips on healthier snack and ways to prepare foods.” | ||

| Material exchange | “They have used several of the recipes from the newsletter.” | |

| Motivation | Direct | “He and I are competing to see who can lose more weight. My change has motivated him to become more active.” |

| “[We] walk together and keep each other motivated. She would not walk if I didn't do it with her.” | ||

| “She tries to follow what I have been eating. So when I started to eat more salad and eat healthier, she did also.” | ||

| Indirect | “I prepare most of the meals so he eats the more balanced meals that I prepare.” | |

| “I buy healthier foods, so there is less junk food in the house.” | ||

| “I have been a good example for her and have shown her how effective diet and exercise can be in leading to weight loss. I inspired her to take an active role in her own health.” |

The theme “lifestyle changes” encompassed a diverse list of new behaviors and attitudes that participants perceived their SSPs adopted since their participation in HELP PD, including eating behaviors, exercise behaviors, emotional changes, and disease preven tion. Eating behaviors included changes in SSPs’ awareness of food, logistical changes in the way SSPs consumed food (eg, timing, content, location of meals), as well as changes in the way SSPs shopped for and prepared food. The overwhelming majority of participants’ responses conveyed positive changes to eating behaviors, ie, increasing awareness of ingredients, decreasing unhealthy foods, and demonstrating initiative to improve recipes. Perceived change in SSPs’ exercise behaviors included changes in physical activity routines, including the location, type, and frequency of these behaviors. Similarly, most participants perceived beneficial changes in SSPs’ behaviors, ie, going to the gym more, spending more time walking with the participant, and finding ways to stay active when at home and work. Perceived change in emotional status included changes in how SSPs’ felt about themselves and the participant. Many participants reported increased closeness with their SSPs, improvements in SSPs’ self-esteem, and thought that their SPPs had a greater sense of pride and more confidence in them. Finally, participants’ perceived SSPs to have a greater awareness of disease prevention and modifiable medical conditions (eg, type 2 diabetes and hypertension), and thought they would be more successful in reducing their disease risk.

“Knowledge dissemination” was also identified as a theme, as many participant responses concerned methods of information sharing between themselves and their SSPs. These methods included discussions with their SSPs about healthy lifestyle habits, nutrition instruction, offering advice, and physical exchange of HELP PD materials and resources. Commonly reported topics of discussions among the subjects and SSPs included information subjects had learned at the HELP PD group meetings and changes in the way the subjects now consumed or thought about food (ie, portion sizing, reading labels, understanding the importance of fresh versus processed foods). The vast majority of advice and instruction subjects offered was also centered around nutrition, with many reported teaching experiences on how to estimate portion size, read labels, and prepare healthy foods. Finally, many subjects reported sharing the HELP PD resources they had received with their SSPs. These resources included newsletters containing recipes, food logs, and a calorie content book of common foods. Although the vast majority of reported knowledge dissemination was verbal (discussions, advice, teaching), HELP PD material sharing was the only reported physical exchange of information.

A final theme of “Motivation” incorporated both direct and indirect modes by which SSPs were inspired to become healthier. Direct motivation included participants’ reports of competitions between themselves and the SSP to lose weight, reciprocal encouragement between the participant and SSP to maintain healthy habits, and direct attempts by the SSPs to emulate new behaviors modeled by the participant. Participants commonly reported that SSPs’ participation in physical activity was dependent on their own. Indirect motivation included the effect of healthy changes made by the participant, which participants believed to prompt SSPs to take active roles in their own health. Acts of transference were also identified, and included indirect transmission of health behaviors from the participant to the SSP. For participants cohabitating with SSPs, such transference was evident in the food purchasing and preparation behaviors of the participant, which exposed SSPs to healthier food options and made it more difficult to access unhealthy items not readily available in the home.

Separate qualitative analysis of intervention and control data did not reveal any major discrepancies in participants’ perceptions of SSPs. However, many of the most salient themes in the intervention data were also expressed by control participants, though with much less frequency. A few notable differences were present in all themes. Within eating behaviors, far more intervention participants reported increased awareness of food content among SSPs, as well as engaging in new behaviors like reading nutrition labels and counting calories. Within exercise behaviors, intervention participants more often reported their SSPs exercising in gyms, whereas control participants reported them to engage in household chore activities (eg, yard work). Under knowledge dissemination, intervention participants reported more discussions with SSPs regarding eating tips and changes made to their own lifestyle habits, whereas control participants seldom reported sharing of healthy eating instructions with SSPs. Finally, as it pertains to the theme of motivation, there was a higher frequency of intervention participants who considered themselves “examples” or “role models” for their SSPs.

DISCUSSION

The HELP PD study was innovative in successfully translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into a community setting although maintaining significant improvements in intervention outcomes over a 12-month period.18 Relative to the usual care group, quantitative data obtained from intervention participants indicated that their participation in HELP PD more positively influenced the eating and exercise habits of their SSPs. In addition, the amount of weight lost by participants was related to PC in their SSPs’ eating habits, as well as whether or not this change was perceived to be favorable. Though these results are based on participants’ perceptions, they suggest, to some extent, that successfully targeting the eating and exercise habits of individual HELP PD participants may have indirectly resulted in compensatory change in the habits of other nonparticipating members of their social support system.

In qualitative analysis, the 3 emergent themes characterized how participants perceived their participation to influence their SSPs: descriptions of SSP lifestyle changes, methods of knowledge dissemination, and forms of SPPs’ motivation. Within these broad themes, participants expressed ideas concerning SSPs’ eating and exercise behaviors, emotional changes, disease prevention, communication about health behaviors and exchange of information, and direct and indirect methods of SSPs’ motivation. Differences in responses between intervention and control groups included discrepancies in PCs in SSPs’ eating and exercise behaviors, the methods by which participants conveyed information, and the frequency with which participants considered themselves to be role models for the SSPs.

Given that most studies of this nature have examined health benefits gained when subjects in behavioral programs participate concurrently with friends or family members,12-14,16 this study provides a unique perspective on whether such benefits can be disseminated from program participants, like those in HELP PD, to members of their social support system. Although it is important to keep in mind that these data are reflective of participants’ perceptions of SSP behaviors, the consistency of participant responses suggest that some beneficial influences likely occurred in SSPs’ actual health habits.

A similar study has shown that clinically significant outcomes can be achieved in untreated family members of individuals undergoing a behavioral weight loss program; however, their investigation was limited to spouses residing in the same home as the program participant.15 The current study is the first of its kind to examine the effects of a weight loss program on a variety of untreated persons in an individual's social support system. Furthermore, findings suggest not only a significant association between individuals’ participation in a behavioral lifestyle intervention and their perceived ability to positively influence SSPs’ lifestyles, but also that these perceptions contain recurring and insightful themes.

Although intervention and control participants’ qualitative responses contained many similar themes, there were notable differences in the way intervention participants described mechanisms of knowledge dissemination and their roles as “examples” for SSPs. These results shed light on the key ways in which participation in the intervention may have influenced SSPs. Given that intervention participants reported discussions with SSPs, and also provided advice about eating and exercise with much greater frequency than control participants, participation in the intervention may have enabled participants to more effectively share knowledge acquired from HELP PD. Similarly, as intervention participants often perceived themselves as good examples for their SSPs, it is reasonable to assume that the intervention equipped them with skills and behaviors they then wished to model.

The findings from this study have clinical implications for future behavioral lifestyle interventions. It is well established that over-weight and obese individuals tend to cluster in familial and social groups.9-11 Our findings, coupled with other clinically significant outcomes observed in untreated spouses of weight loss participants,15 suggest that programs could be intentionally tailored to teach participants how to share health information to members of their social support network. Our finding that the amount of weight lost in the LWL intervention was related to participants’ PC and favorability of change in SSP's eating habits, provides an additional perspective to that of other studies, where participants who had some form of social support demonstrated better clinical outcomes.12-14

Therefore, a behavioral lifestyle intervention approach targeting both formally enrolled participants as well as their SSPs may enhance weight loss, and potentially other clinical outcomes, for both parties.

There are several limitations to the current study. Most notably, the qualitative methodology relied on subjective interpretation of questionnaire responses. Furthermore, it is important to note that participants in the HELP PD intervention were not explicitly encouraged to share their knowledge or skills learned in HELP PD, though we anticipate that this may have happened for some, and less for others. The HELP PD intervention included information on identifying social support for lifestyle changes and building an environment for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance. Thus, the nature of this intervention may have had an impact on family and social interactions in the home resulting in change to nutrition, exercise habits, and other weight-related behaviors. If participants did not find it necessary to share information with others in their social networks, it is less likely that these SSPs would have been influenced. In addition, the responses presented here are representations of participants’ perceptions of SSPs rather than actual measured change in behaviors, attitudes, or motivation. This study is also limited as it presumed SSPs to be external to the study, though 2 participants indicated that their SSPs were also HELP PD participants. Thus, it is difficult to know whether participants’ PCs in SSPs were due to the influence of the participant responding, the SSPs’ potential participation in the study, or a combination of both. Finally, this study is limited by sample size, as those who responded to questionnaires represent only a small percentage (24%) of the entire HELP PD study population. Although themes were consistent throughout the data, better insight may have been obtained with a larger sample size. However, it appeared saturation had been achieved, as no additional themes or information emerged as interviews and analysis progressed.

Regarding quantitative methodological limitations, interpretation of results may be limited by the fact that surveys not designed to detect at what time point knowledge dissemination may have occurred during the intervention. Enrollment in HELP PD began in 2007 and ended in 2009, with participants enrolled in groups of 20-25 to allow for formation of an intervention group every 4-6 weeks. This survey was collected during a 3-month period in the summer of 2009 during assessment visits that occurred semiannually. Therefore, participants were surveyed at different time points in their participation, ranging from 6 to 24 months, and had been exposed to the intervention for varying lengths of time. Whether or not this influenced survey responses is indeterminable. Additional limitations of the quantitative component of the HELP PD study at large have been published previously.18-20

These findings present many implications for future research, and contribute to a larger body of work suggesting a clinically significant relationship between those undergoing behavioral lifestyle interventions and members of their social support networks.12-14,16

Although this study provided insight regarding how behavioral intervention participants perceived their influence on SSPs, future interventions would benefit from understanding the actual perceptions of SSPs, as well. This type of inquiry would help determine if participants and SSPs agree on the type of influence exerted on each other, and identify discrepancies in perceptions that have yet to be delineated. Salient themes identified in this study, such as methods of knowledge dissemination and motivation, suggest that certain elements of lifestyle interventions may be specifically targeted to optimize results for both participants and their surrounding social support system. Furthermore, investigations into the role of SSPs in weight loss and diabetes prevention programs could be beneficial to pediatric populations as well. Given that studies of pediatric weight management programs indicate family-based approaches to be the most effective,22-25 investigating the social structure of families could elucidate further information about the role of SSPs within the family, and their influence on both children's and parents’ health behaviors.

The role of social support in behavioral lifestyle changes is still not fully understood. Through a mixed-methods approach, this study quantitatively examined how participants’ perceptions of their SSPs’ lifestyle changes related to their own participation and weight loss, and qualitatively identified themes extant within these perceptions. Results gleaned from this study in participants with prediabetes provide valuable insight on the indirect health influences exerted within social circles, potentially as a corollary of participation in a weight loss program. With such high prevalence of diabetes and obesity, prevention and treatment approaches must have greater reach to make a substantial impact on this epidemic, which may be achieved by influencing social circles. The results of this study provide guidance to those wishing to expand the reach of programs, and insight to the means of influencing the health behaviors of program participants and their support network. Additional research is warranted to fully elucidate the influence of these social interactions in supporting weight loss and diabetes prevention efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jeff Ambrose, MD, for his assistance in the conduct of this study. This study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R18DK06990 and 1R18DK069901). Ms Bishop was supported by the NIH Short Term Training for Medical Students Award (5T35DK007400-33). Dr Skelton was supported in part through an NICHD/NIH Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23 HD061597).

Footnotes

No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Byrd-Holt DD, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2002. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1263–1268. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of over-weight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA. 2004;291(23):2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–490. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein EA, Khavjou OA, Thompson H, et al. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. [July 31, 2012];2011 National Diabetes Fact Sheet. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/estimates11.htm.

- 6.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Mill-wood) 2009;28(5):w822–w831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang YC, McPherson K, Marsh T, Gortmaker SL, Brown M. Health and economic burden of the projected obesity trends in the USA and the UK. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):815–825. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(4):370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leahey TM, Gokee LaRose J, Fava JL, Wing RR. Social influences are associated with BMI and weight loss intentions in young adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;19(6):1157–1162. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahr DB, Browning RC, Wyatt HR, Hill JO. Exploiting social networks to mitigate the obesity epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17(4):723–728. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kiernan M, Moore SD, Schoffman DE, et al. Social support for healthy behaviors: scale psychometrics and prediction of weight loss among women in a behavioral program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(4):756–764. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verheijden MW, Bakx JC, van Weel C, Koelen MA, van Staveren WA. Role of social support in lifestyle-focused weight management interventions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(suppl 1):S179–S186. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black DR, Gleser LJ, Kooyers KJ. A meta-analytic evaluation of couples weight-loss programs. Health Psychol. 1990;9(3):330–347. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorin AA, Wing RR, Fava JL, et al. Weight loss treatment influences untreated spouses and the home environment: evidence of a ripple effect. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(11):1678–1684. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorin A, Phelan S, Tate D, Sherwood N, Jeffery R, Wing R. Involving support partners in obesity treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(2):341–343. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katula JA, Vitolins MZ, Rosenberger EL, et al. One-year results of a community-based translation of the Diabetes Prevention Program: Healthy-Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes (HELP PD) Project. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(7):1451–1457. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katula JA, Vitolins MZ, Rosenberger EL, et al. Healthy Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes (HELP PD): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2010;31(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blackwell CS, Foster KA, Isom S, et al. Healthy Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes: recruitment and baseline characteristics. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Sage Publications Ltd; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar DR. Childhood obesity treatment: targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(5):1008–1015. doi: 10.1079/bjn20061757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janicke DM, Sallinen BJ, Perri MG, et al. Comparison of parent-only vs family-based interventions for over-weight children in underserved rural settings: outcomes from project STORY. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(12):1119–1125. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kitzmann KM, Beech BM. Family-based interventions for pediatric obesity: methodological and conceptual challenges from family psychology. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20(2):175–189. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol. 1994;13(5):373–383. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.5.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]