Abstract

Background

Despite recognition of the benefits associated with well-controlled diabetes and hypertension, control remains suboptimal. Effective interventions for these conditions have been studied within academic settings, but interventions targeting both conditions have rarely been tested in community settings. We describe the design and baseline results of a trial evaluating a behavioral intervention among community patients with poorly-controlled diabetes and comorbid hypertension.

Methods

Tailored Case Management for Diabetes and Hypertension (TEACH-DM) is a 24-month randomized, controlled trial evaluating a telephone-delivered behavioral intervention for diabetes and hypertension versus attention control. The study recruited from nine community practices. The nurse-administered intervention targets 3 areas: 1) cultivation of healthful behaviors for diabetes and hypertension control; 2) provision of fundamentals to support attainment of healthful behaviors; and 3) identification and correction of patient-specific barriers to adopting healthful behaviors. Hemoglobin A1c and blood pressure measured at 6, 12, and 24 months are co-primary outcomes. Secondary outcomes include self-efficacy, self-reported medication adherence, exercise, and cost-effectiveness.

Results

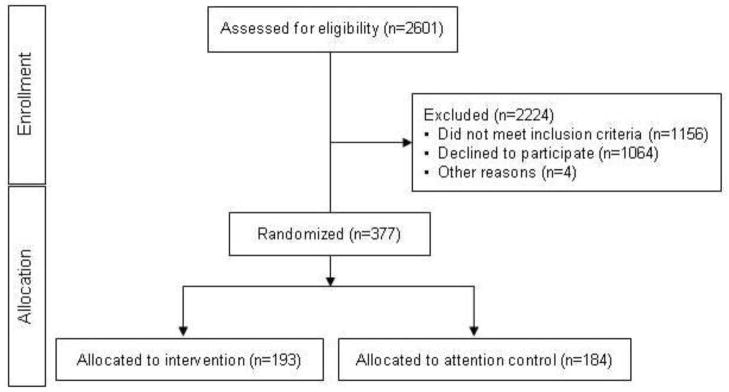

Of 377 randomized patients, 193 were allocated to the intervention and 184 to attention control. The cohort is balanced in terms of gender, race, education level, and income. The cohort’s mean baseline hemoglobin A1c and blood pressure are above goal, and mean baseline body mass index falls in the obese range. Baseline self-reported non-adherence is high for diabetes and hypertension medications. Trial results are pending.

Conclusions

If effective, the TEACH-DM intervention’s telephone-based delivery strategy and nurse administration make it well-suited for rapid implementation and broad dissemination in community settings.

Keywords: Diabetes, Hypertension, Behavioral Intervention, Telemedicine, Self-management, Case Management

Introduction

Poor diabetes control is a substantial public health problem, and annual costs of diabetes now approach $245 billion.[1,2] Treatment to improve blood glucose can prevent diabetes complications and reduce costs.[3–7] Despite the evidence supporting glycemic control, fewer than 60% of diabetes patients achieve recommended blood glucose goals (hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) <7.0%).[8,9]

Approximately 75% of all patients with diabetes have concurrent hypertension.[9] While blood glucose control is the focus of diabetes management for most patients, data suggest that blood pressure (BP) control may benefit patients with diabetes even more than blood sugar reduction.[7] Evidence from several randomized controlled trials demonstrates that BP control reduces microvascular complications, cardiovascular complications, and overall mortality among patients with diabetes, and improves health-related quality of life.[7,10–12] Additionally, BP control may be even more cost-effective than glycemic control in patients with diabetes.[7] Despite the risks of hypertension in diabetes, as few as 25% of hypertensive patients with diabetes have sufficient BP control.[13,14]

Because blood glucose and BP control are both important targets for patients with diabetes, simultaneously addressing these parameters could drastically lessen the public health burden of diabetes. Though studies have evaluated interventions designed to improve blood sugar and/or BP control,[15–18] a limitation of the existing evidence is that it largely derives from studies performed in academic medical centers. If best practice is to become standard practice, diabetes interventions must demonstrate effectiveness in community settings, where barriers to quality care may differ from the academic context.[19] An intervention proven to simultaneously impact diabetes and hypertension outcomes in the community setting could be widely adopted and greatly impact patient morbidity and mortality.

We are currently conducting a randomized, controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the effectiveness of a telephone-delivered, nurse-administered, behavioral intervention among community patients with poorly-controlled diabetes and comorbid hypertension. This intervention is designed to simultaneously improve patient self-management of both blood glucose and BP. In order to establish the effectiveness of this intervention in a broadly generalizable population, this RCT takes place in a community primary care setting. We describe the design and design considerations of conducting this RCT in a community primary care setting, and provide baseline characteristics of the study sample.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Population

Tailored Case Management for Diabetes and Hypertension (TEACH-DM) is an ongoing 2-arm RCT in which patients with poorly-controlled type 2 diabetes and hypertension receive a behavioral intervention or attention control over 24 months (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00978835). The study population derives from nine community practices in the Duke Primary Care Research Consortium (PCRC). The Duke PCRC is a community-based research network established in 1997, and is a member of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Practice-Based Research Network registry. The goals of the Duke PCRC are to: 1) perform clinical studies to improve health care delivery and patient outcomes; 2) provide opportunities for clinicians to develop new research skills; 3) support clinician researchers by providing administrative support and trained study coordinators; and 4) generate research to support the practice of evidence-based medicine.[20]

We are conducting this study in Duke PCRC clinics because these community practices function outside the traditional academic context. Prior disease management intervention studies have typically been performed in academic or not-for-profit HMO-based populations, which lack generalizability to community settings; our study sites therefore represent a novel setting for evaluating a nurse-delivered, behavioral, telephone intervention for diabetes and hypertension. Further, this setting is relevant to real-world practice, because patients with less proximity to tertiary care may benefit most from telephone-based interventions. The study is approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Clinic Identification and Engagement

At study outset, community clinics were approached by the Duke PCRC director (RJD) to discuss study participation. An in-person presentation of the study’s design, objectives and procedures was followed by an opportunity for clinicians to ask questions and offer suggestions for recruitment and implementation at their clinic. Nine primary care practices (6 Family Medicine, 3 Internal Medicine) agreed to participate. Periodic updates regarding recruitment and retention are provided to the clinics during the study, and study results will be disseminated to clinics for their feedback and interpretation prior to submission of the final study progress report.

Study Population and Recruitment

Study patients must: be older than 21; be enrolled in a participating Duke PCRC clinic for ≥1 year; have diagnosed type 2 diabetes requiring medication (presence of an ICD-9 code of 250.x0 or 250.x2 on outpatient electronic encounter forms for the year prior to enrollment, along with a prescription for oral hypoglycemic medication or insulin during the previous year); have diagnosed hypertension requiring medication (presence of an ICD-9 code of 401.0, 401.1, or 401.9 on outpatient electronic encounter forms for the year before enrollment, along with receipt of a prescription for an antihypertensive medication during the previous year); and have poor diabetes control (most recent HbA1c within the past year ≥7.5%). While poor glycemic control is required for inclusion, poor BP control is not. Because diabetes, hypertension, and related complications disproportionately affect African Americans,[21,22] we have aimed to recruit a sample that is approximately 45% African-American, which mirrors our local population.

Exclusion criteria include: fewer than one primary care clinic visit during the previous year; hospitalization for a stroke, myocardial infarction, or coronary artery revascularization in the past 6 months; active diagnosis of dementia, psychosis, or metastatic cancer; type 1 diabetes as confirmed by primary care provider (PCP); lack of telephone access or severely impaired hearing or speech (as patients must be able to receive and respond to phone calls); inability to speak English; refusal to provide informed consent; residence in a nursing home or receipt of home health care; participation in another hypertension or diabetes study. Of note, patients that switch clinics within the Duke PCRC may continue in the study, but those leaving the PCRC during the study are withdrawn from the trial. Because Endocrinology referral is within the scope of usual care for community-based diabetes patients, PCP co-management with Endocrinology is not a study exclusion criterion. One participating Duke PCRC clinic has an on-site Endocrinologist, and PCPs at other sites are able to refer to nearby Endocrinology practices.

Patient Identification, Enrollment, and Randomization

Study enrollment is complete. Blinded study staff members, separate from the interventionist and intervention support team, managed patient identification and enrollment; randomization was managed remotely by the study data manager. Patients meeting study inclusion criteria were identified using Duke PCRC administrative data. After patient identification, letters signed by the study PI and patient’s PCP were sent to preliminarily eligible patients. These letters described the study in general terms and instructed patients to call a toll-free number to opt out of study participation or receive more information. We chose this ‘opt-out’ approach to initiating patient contact because it partially mitigates volunteer bias by facilitating the inclusion of prospective subjects that are interested in study participation, but are too busy or distracted to call for information. After the opt-out period, study staff contacted patients by telephone to explain the study and, if appropriate, arrange an in-person meeting at the patient’s clinic site to further evaluate eligibility and obtain informed consent. After providing informed consent for study participation at this meeting, preliminarily eligible patients completed the baseline study survey, which collected demographic, clinical, socioeconomic, and psychosocial data. This baseline interview required approximately 45–60 minutes. BP and HbA1c were also collected at the time of this baseline assessment.

Following the baseline assessment, the study data manager randomized patients meeting all eligibility criteria to the TEACH-DM intervention or an attention control. Randomization was based on a computer-generated randomization sequence maintained by the study data manager at a site separate from the site of patient enrollment. The randomization sequence was integrated with the study tracking database; once an eligible patient was enrolled in the study and baseline assessment was completed, the data manager could populate the randomization field in the tracking database with the patient’s group assignment by clicking a button. The data manager then contacted patients by phone with their randomization assignment. Study staff responsible for data collection remained blinded to randomization assignments throughout the study. Primary care providers also remained blinded to patient randomization status, unless a patient chose to reveal his/her assignment.

TEACH-DM Intervention Design

The TEACH-DM study evaluates a telephone-delivered, nurse-administered behavioral intervention targeting patients with poorly-controlled type 2 diabetes and comorbid hypertension. The intervention comprises modules that address 3 content areas: 1) cultivation of healthful behaviors for diabetes and hypertension control; 2) provision of fundamentals to support attainment of the healthful behaviors; and 3) identification and correction of patient-specific barriers to adopting healthful behaviors (Table 1). Modules are delivered according to a patient-specific schedule (Appendix A) that is constructed for each patient at study start based on: 1) patient preferences regarding certain modules; and 2) presence of certain parameters such a high body mass index or use of insulin.

Table 1.

Components of TEACH-DM intervention

| Module category | Module content areas |

|---|---|

| Healthful behaviors for diabetes and hypertension control | Medication adherence |

| Weight loss | |

| Diet planning (low sodium/low glycemic index diet, portion control) | |

| Exercise | |

| Smoking cessation | |

| Alcohol cessation | |

| Fundamentals supporting attainment of healthful behaviors | Basic diabetes and hypertension knowledge |

| Insulin self-management | |

| Hypoglycemia prevention/management | |

| Stress management | |

| Engaging providers in shared decision-making | |

| Patient-specific barriers to healthful behaviors | Low health literacy |

| Poor memory | |

| Fear of side effects | |

| Lack of social support |

TEACH-DM intervention modules addressing the cultivation of healthful behaviors target topic including medication adherence, weight loss, diet planning (low sodium, low glycemic index, portion control), exercise, smoking cessation, and moderation of alcohol intake. Specific educational modules assess the relevance of each behavior for the patient, identify the patient’s stage of change for relevant behaviors based on the transtheoretical model,[23,24] and then seek to modify relevant behaviors and improve glycemic and BP control by providing information tailored to the patient’s stage of change. Intervention module content is based upon American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Seventh Joint National Committee (JNC-VII) guidelines.[25–27] Verbal information is reinforced with low-health literacy handouts. In addition to these modules, the nurse provides patients with information regarding available community resources targeting relevant behaviors.

Other TEACH-DM modules provide fundamentals that support attainment of healthful behaviors. These fundamentals include basic diabetes and hypertension knowledge, self-managing insulin, preventing and managing hypoglycemia, stress management, and engaging healthcare providers in shared decision-making. As with the health behavior modules, the fundamental modules assess the relevance of each area to the patient and provide patient-tailored information.

Finally, additional TEACH-DM modules identify and address patient-specific barriers to adopting healthful behaviors. We chose a list of potential barriers using the Health Decision Model (HDM) as our primary theoretical model,[28] and demonstrated these factors (low health literacy, poor memory, fear of side effects, and lack of social support) to be associated with suboptimal disease control in preliminary work.[29] Modules ascertain the extent to which each potential barrier represents a challenge for the patient, and provide tailored information geared toward rectifying relevant barriers.

Tailored interventions like TEACH-DM offer advantages in comparison to generic interventions. Through tailoring, interventionists can identify issues that are relevant to particular patients, and cover them in a patient-specific manner.[30–31] Further, tailored interventions can address multiple problem behaviors and barriers to chronic disease control, which is valuable because multiple challenges frequently underlie poor glycemic or BP control. The nurse interventionist for TEACH-DM uses a computer database with scripts and tailoring algorithms in order to ensure standardization of tailored information.

Use of telephone delivery for the TEACH-DM intervention also carries advantages. Telephone-delivered interventions can positively change behavior and improve chronic disease management.[32,33] Telephonic delivery strategies can also be implemented relatively easily among large patient panels, and may enhance cost-effectiveness by reducing clinic visits.[34,35] Telephone interventions are particularly relevant for community populations, which are typically distributed over large geographic areas and lack access to disease management interventions. The TEACH-DM intervention is amenable to administration via both mobile and landline phones, further enhancing access among community patients.

Strong evidence supports using nurse interventionists to implement behavioral interventions like TEACH-DM. Nurse-administered interventions increase treatment adherence among hypertensive patients,[36] improve BP control,[37–39] and improve outcomes for other diseases.[38,39] The nurse implementing this study’s behavioral intervention has extensive experience in clinical and research-based case management, and served as an interventionist for a prior study of a similar health services intervention targeting hypertension. Our interventionist has also received several hours of didactic training in core case management strategies (e.g., motivational interviewing), diabetes management, principles of telephone-based care, and use of the tailoring strategies for this intervention. An expert clinical team (a General Internist, an Endocrinologist, and 2 nurse specialists) is available to the nurse interventionist at all times, and the nurse interventionist and clinical team hold monthly meetings to discuss patient issues.

Case management that is fully integrated into primary care sites has been shown to be effective, which may represent a disadvantage to the centralized nurse interventionist model utilized for the TEACH-DM intervention.[40] However, because community practices often lack the resources to provide nurse case management for multiple conditions,[41] the TEACH-DM intervention delivery model represents a practical strategy for increasing access to this beneficial resource for community patients. Further, we have taken steps to integrate our nurse interventionist into the participating community practices by: 1) conducting introductory site visits where each site’s specific resources and care processes were reviewed; 2) tailoring educational materials to locally available resources (e.g., referral to local diabetes education programs); and 3) assuring electronic access to clinic medication lists and notes to facilitate review of PCP treatment plans.

Intervention Group Procedures

Within two weeks of randomization, the nurse interventionist calls each intervention arm patient for introductions and initiation of the first encounter. During scheduled telephone contacts every eight weeks thereafter, the nurse delivers intervention modules from the 3 content areas from Table 1. Modules are delivered based on a patient-specific fixed schedule (Appendix A). For each scheduled call, the nurse interventionist makes at least 4 attempts to reach the subject on a mutually agreed-upon day and time. If all attempts at a scheduled call fail, the interventionist mails a letter asking patients to call a toll-free study number to arrange a follow-up call. When modules cannot be completed, the module schedule shifts back, such that the missed module is covered at the next encounter. Subjects who miss encounters therefore do not complete all 12 modules. Between scheduled calls, patients may call the nurse interventionist with questions related to their diabetes and hypertension. Should urgent health care issues arise during or as a result of any study calls, the nurse either contacts the patient’s PCP/study physician or else refers patient for emergency care if indicated.

The nurse interventionist conducts all calls while logged on to the study’s intervention tracking database. This database contains the standardized module scripts. The tracking database records the modules delivered to each patient, as well as the number/duration of scheduled or unscheduled calls to assist with cost analysis. Information gathered during all calls is recorded in the tracking database. In order to measure intervention fidelity, the interventionist reviews patient-specific checklists at each call, which are maintained in the intervention database. This study also utilizes a quality assurance process whereby clinical experts listen in on study calls periodically to assess intervention fidelity and monitor for possible safety concerns.

The intervention lasts 24 months. This length was chosen to measure intervention effectiveness and sustainability; few studies of patient interventions have a two-year intervention length. Blinded study staff contact patients to arrange BP and HbA1c measurement at 6, 12, and 24 months after enrollment (4 total measurements including baseline assessment). Additionally, patients complete secondary outcome measure assessment with blinded study staff at 6, 12, and 24 months.

Attention Control Group Procedures

Patients randomized to the attention control group receive PCP diabetes and hypertension management, and additional health behavior counseling by study staff focused on issues other than diabetes and hypertension. The interventionist delivers control modules according to the same intervals as the intervention, with scheduled calls every 8 weeks for 24 months. Control modules include information and recommendations regarding several common chronic conditions, including: 1) medication safety, 2) eye problems, 3) colorectal cancer, 4) skin cancer, 5) breast cancer or prostate cancer (gender-specific), 6) osteoporosis, 7) osteoarthritis, 8) gastroesophageal reflux, 9) exercise in hot weather, 10) adult vaccinations, 11) sleep disturbance, and 12) back safety. These modules are based on information from the National Institutes of Health. Outcome assessment for attention control patients is identical to the intervention group.

Primary Outcomes

Glycemic and BP control are co-primary outcomes for this study, and we have chosen cut-points for these outcomes that are consistent with JNC VII standards,[25] and with ADA standards during the study enrollment period.[43] Outcome assessment occurs at 6, 12, and 24 months, with 12 months being the primary assessment time point. HbA1c measurement uses standard high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods, on a machine calibrated to the national standard (mean =5.0%, top of normal range =6.0%). Glycemic control is coded as a dichotomous variable with HbA1c ≤7.0% indicative of good glycemic control and HbA1c >7.0% as poor glycemic control.

For BP measurement, after the patient has sat comfortably for 5 minutes, two BP measures are obtained at 5-minute intervals and averaged. All BP measurements are performed with electronic, upper arm BP cuffs (Omron® ReliOn®), which are equivalent to the gold standard of random zero sphygmomanometers.[42] BP control is coded as a dichotomous variable with BP (SBP) <130 mmHg and diastolic BP (DBP) <80 mmHg indicative of good BP control and either SBP >=130 mmHg or DBP >=80 mmHg as poor BP control.

Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes for the TEACH-DM study include self-efficacy,[44,45] self-reported medication adherence,[46] and exercise.[47] Table 2 summarizes secondary outcome measures assessed. We also screen for adverse events during each intervention or attention control call, and systematically ascertain adverse events at all scientific visits.

Table 2.

TEACH-DM secondary outcomes.

| Secondary outcome | Measure | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Self-efficacy | Perceived Competence Scale [44] | 4-item scale, each item scored 1–5, summed scores range from 4–20, higher score represents lower self-efficacy |

| Hypertension self- efficacy measure [45] | 4-item scale, each item scored 1–4, summed score range 4–16, higher score represents higher self-efficacy | |

| Self-reported medication adherence | Medication-Taking Scale [46] | 4-item scale, each item scored 1–4, score ≤2 on any item represents non-adherence |

| Exercise | International physical activity questionnaire [47] | 12-item scale, yields continuous estimate of total MET metabolic equivalents of task in minutes per week |

Utilization/Cost Outcomes

Another study aim is cost analysis. In order to estimate the net cost of the intervention, we carefully measure intervention implementation using the study’s tracking database (see “Intervention Group Procedures” above) and track patients’ health service utilization. At study end, the PCRC will access study patient medical records to tabulate visits, medications, hospitalizations, and diagnostic tests, which we will compile into a cost for each patient (see “Economic Analyses” below). We will also assess self-reported utilization for completeness.

Sample Size and Power Considerations

Unlike poor glycemic control, poor BP control is not a study inclusion criterion. Because not all study patients have suboptimal BP control, a larger cohort is required to demonstrate an improvement in this measure. The study’s sample size calculation was therefore based on the BP control co-primary outcome.

We performed sample size calculations using information about expected proportions with well-controlled BP during the study and the correlation structure of repeated measurements within patients over time. Formulas and software by Rochon were used to estimate sample size.[48] Preliminary data suggested a baseline rate of BP control in our study population of 40%. In the intervention group, we assumed a 20% increase in BP control at 12 months, from 40% at baseline to 60% by study end. This 20% increase in BP control was chosen because it was felt that an intervention of this intensity may require a large effect to justify its implementation costs. In the attention control group, we assumed a constant BP control rate of 40% during the study, which is consistent with observed trends in our group’s prior work.[49] We also conservatively assumed an autoregressive correlation structure with an estimated correlation between two adjacent measurements of 0.2.[50] In addition, we assumed a 20% dropout rate. Using a type-I error rate of 5%, we estimated a sample size of 200 subjects in each arm was needed to have 80% power to detect a 20% change in proportion of BP control over time (400 patients total).

With this sample size and a type-I error rate of 5%, we estimated that we would have 80% power to detect a 10% change in proportion with glycemic control at 12 months (e.g., an increase in the proportion with glycemic control to 20% in the intervention group versus an increase to 10% in the attention control group).

Primary Analyses

Our co-primary outcome variables (HbA1c and BP control) are binary and longitudinal; both are measured at baseline, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months. We plan to address the main study hypotheses using generalized estimating equation (GEE) methods.[51] GEEs estimate “population-average” or “marginal” effects in clustered or longitudinal data. The regression coefficients from a marginal model have essentially the same interpretation as those from a cross-sectional regression analysis. Through the correlation structure we incorporate the within-subject correlation that is inherent in these longitudinal data. For both hypotheses, we will use empirical standard errors and either an unstructured or autoregressive correlation structure for inference, as they are robust to misspecifications of the correlation structure. We plan to estimate the parameters in the models using the SAS procedure GENMOD (SAS Version 9.2, Cary, NC).

Secondary Analyses

Most secondary outcomes for this study are continuous, longitudinal outcomes measured at baseline, 6, 12, and 24 months. We will fit linear mixed effects models using the SAS procedure PROC MIXED (SAS Version 9.2, Cary, NC) to test hypotheses about the intervention effect.[52] For self-reported medication adherence, which is measured on a 0–4 scale, we will use a GEE model with a distribution and link function that will depend on our assessment of the distribution of scores across the 5 categories.

As an additional secondary analysis, we will use linear mixed effects models to examine HbA1c and BP as continuous outcome variables.

Economic Analyses

We will analyze the cost of implementing the TEACH-DM intervention, the incremental effects on health care resource utilization of the intervention compared to usual care, and the incremental cost-effectiveness of the intervention in comparison to usual care. We will use a micro-costing approach where we measure labor and non-labor inputs (e.g., patient education materials) to estimate the cost of the intervention. In assessing effects on health care resource utilization we will limit our analysis to costs incurred by patients in the two study arms at Duke University primary care clinics and hospital. These costs will be collected from Duke University Health System administrative data. As medication prescriptions can be filled at a variety of locations, we will obtain representative market prices of medications using the “Price Checker” available at Costco.com’s pharmacy website. Because cost data will be collected over a 4-year period, we will use the Consumer Price Index to standardize costs from different years to derive constant dollars for analysis. Costs will be further normalized by discounting future costs at 3%. We will account for two main categories of costs: intervention costs and resource utilization costs. Effectiveness measures will be glycemic control, BP control, and estimated long-term survival. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios will be calculated for each of the three effectiveness measures (glycemic control, BP control, and survival). We plan to use the CDC-RTI Diabetes Costs-Effectiveness Model to estimate life expectancy and incremental cost-effectiveness.[53]

Results

Recruitment for TEACH-DM began on June 11, 2009 and concluded July 27, 2011. Administrative PCRC data was obtained for 3581 patients with uncontrolled diabetes from the nine participating community practices. Initial study recruitment letters were sent to 2601 patients. Of this group, 453 patients were ultimately consented for participation, and 377 randomized; 76 patients were excluded after consent and before randomization, mostly due to baseline HbA1c below 7.5%. Of the 377 randomized patients, 193 were allocated into the intervention group and 184 to attention control (Figure 1). Of note, in randomizing 377 patients, we fell approximately 6% short of our anticipated recruitment goal.

Figure 1.

TEACH-DM recruitment patient flow diagram.

The TEACH-DM study arms are well-balanced in terms of gender, race, marital status, education level, and annual income (Table 2). As expected, baseline HbA1c was elevated for both groups. Mean baseline systolic BP was higher than recommended for patients with diabetes, and BP was well-controlled in only 21.5% of the cohort. Mean baseline BMI fell in the obese range. Almost half of patients have a history of tobacco use, but only 10.6% are current smokers. Baseline self-reported non-adherence for diabetes medications was higher than for hypertension medications (43.0% to 29.2%).

Discussion

Despite widespread recognition of the benefits associated with diabetes and hypertension control, rates of control for these conditions remain suboptimal. Though effective interventions exist for diabetes and hypertension,[15–18] interventions proven to simultaneously impact outcomes for both conditions in the community setting are urgently needed. We are evaluating the telephone-delivered, nurse-administered TEACH-DM intervention among community patients with poorly-controlled diabetes and comorbid hypertension. At the conclusion of the 24-month study period, we will assess the impact of the TEACH-DM intervention among our community cohort, with outcomes including diabetes and hypertension control, diabetes and hypertension-related self-efficacy, self-reported adherence to diabetes and hypertension medications, exercise, and diet. We will also assess the costs and cost-effectiveness of implementing the intervention in community practices.

This study is an example of type 3 translational research,[54] in which findings from randomized trials of methods of health care delivery are translated into real-world practice. If this study shows the TEACH-DM intervention to be effective in the community setting, the intervention will be ready for implementation almost immediately and without alteration. This intervention’s telephone-based delivery strategy and nurse administration make it well-suited for broad dissemination in community settings, and likely to be cost-effective. An additional strength of this study is our diverse and balanced patient population, which helps assure that our findings will be widely generalizable.

Challenges to Study Implementation

Conducting the TEACH-DM study in the community setting has presented unique challenges, which are worth noting in order to inform the development of future community-based studies, as well as the interpretation of the current study’s results when they are available. These included patient- and practice-level challenges.

We have noted multiple patient-level challenges to the conduct of this study. For example, many patients have changed employment or become unemployed during the study period, which has led to alterations in insurance carriers or even loss of insurance coverage; consequently, some patients have experienced interruptions in their medical care. Employment and insurance coverage issues may be particularly relevant for rural community patients, who may have limited vocational options. Next, patients have frequently changed contact phone numbers without leaving forwarding information, at times making intervention calls challenging. Frequent reconciliation of our study database with the Duke clinical information system has mitigated this issue partially but not completely. Finally, we have noted that multiple competing diabetes studies are taking place in the PCRC clinics, many of which are industry-funded with higher patient compensation. This issue has created competition in recruiting research patients, which was likely a factor in our falling short of our anticipated recruitment goal.

We have also encountered practice-level challenges to conduct of this study, many of which are unique to the community setting. For instance, most of the included community practices are not explicitly organized to accommodate research, so study enrollment procedures were limited to certain time periods due to space limitations. This may have contributed to our falling short of our expected enrollment. Additionally, we attempted to structure our enrollment and follow-up processes to minimally interfere with clinic flow; however, this occasionally failed, creating frustration on the part of the clinic staff. Finally, two study sites have undergone reorganization and personnel changes during the study period. This has resulted in doctors taking patients with them to a new practice not participating in our study. Turnover among non-physician staff has at times resulted in confusion in processing research visits for newer clinic staff members who are less familiar with the TEACH-DM study protocol.

As noted, some of these patient- and practice-level challenges likely contributed to our falling 6% short of our pre-specified recruiting goal for the TEACH-DM study. However, we feel that this modest shortfall is unlikely to impact the validity of the study, as we made very conservative initial assumptions about standard deviations of outcome measures for our power calculations.

Limitations

Certain study limitations may affect interpretation of our findings. Our population is nearly half African-American, and has a high incidence of patients with financial insecurity and low literacy. Our findings may therefore not generalize to populations with differing demographics. Likewise, our study population included a relatively low percentage of patients with adequate BP control; implementing this protocol in populations with higher or lower prevalence of poorly-controlled BP may affect the intervention’s impact on BP control. We used an experienced nurse to implement the TEACH-DM intervention, and use of a less experienced nurse could affect the intervention’s impact on diabetes and BP control.

Study randomization occurred at the patient level, so the theoretical possibility exists for contamination within study sites or PCP patient panels. As this intervention operates independently of PCPs (save for in the event of a safety concern, which is rare), we feel that there is low potential for such contamination. However, because we cannot rule out that an activated intervention patient could impact the practice of his or her PCP, who in turn might then activate control patients, this may be a study limitation.

Finally, treatment goals for diabetes and hypertension have evolved in recent years,[55] and it is possible that the targets we are utilizing for this study may not be optimal for all patients. We initially chose these treatment goals based on guidelines that were widely accepted throughout most of the study period.[25,43] However, well after study enrollment was complete and follow-up nearly concluded, debate arose about these targets. Given that this debate began late in the study, we felt it would be unreasonable to change our treatment goals. Even before the recent debate about diabetes and hypertension treatment goals, we had chosen to conduct systematic adverse event ascertainment at all scientific visits during the trial, and will report these findings with our primary results.

Conclusions

Despite the challenges inherent in conducting community-based research, interventions proven to simultaneously impact diabetes and hypertension outcomes in the community setting are needed to reduce the public heath burden of these conditions. If effective, the TEACH-DM intervention could address this need, as its telephone-based delivery strategy and nurse administration will make it appropriate for rapid implementation and broad dissemination in community settings.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

TEACH-DM study population baseline characteristics

| Demographicsa | Total (N=377) | Intervention (N=193) | Attention Control (N=184) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 58.7 (10.9) | 57.8 (10.9) | 59.6 (10.7) |

| Male Gender | 45.4% | 45.6% | 45.1% |

| Raceb | |||

| African-American | 48.5% | 48.7% | 48.4% |

| White | 49.9% | 49.2% | 50.5% |

| Other | 1.6% | 2.1% | 1.1% |

| Married | 60.2% | 58.5% | 62.0% |

| High School Education or Less | 49.1% | 47.2% | 51.1% |

| Employment Status | |||

| Full-time | 38.2% | 39.9% | 36.4% |

| Part-time | 5.8% | 2.6% | 9.2% |

| Not employed/retired | 54.9% | 56.5% | 53.3% |

| Financial Situation | |||

| Can pay bills without cutting spending | 58.1% | 61.1% | 54.9% |

| Can pay bills only by cutting spending, or cannot always pay bills | 41.7% | 38.3% | 45.1% |

| Annual Income | |||

| <$10.000 | 5.8% | 6.7% | 4.9% |

| $10.000–20,000 | 13.0% | 9.3% | 16.8% |

| $20,001–35,000 | 26.3% | 27.5% | 25.0% |

| $35,001–50,000 | 16.4% | 15.5% | 17.4% |

| >$50,000 | 24.7% | 25.4% | 23.9% |

| Low Health Literacy (≤60 on REALM) | 31.0% | 31.6% | 30.4% |

| Clinical Data | |||

| HbA1c (%), mean (SD) | 9.1(1.5) | 9.2(1.5) | 9.0(1.4) |

| SBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 142.2(20.3) | 142.0(20.7) | 142.5(20.0) |

| BP well-controlled (<130/80 mmHg) | 21.5% | 21.8% | 21.2% |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 36.3 (7.7) | 36.2 (7.9) | 36.4 (7.5) |

| Tobacco Use | 10.6% | 13.5% | 7.6% |

| Total MET Min per Week, mean (SD) | 652.1(1317.3) | 536.8(1100.0) | 772.4(1504.8) |

| Perceived Competence Scale, mean (SD) | 2.5(0.8) | 2.5(0.8) | 2.4(0.8) |

| Medication Adherence (Medication Taking Scale) | |||

| Hypertension medications | 29.2% | 26.9% | 31.5% |

| Diabetes medications | 43.0% | 43.0% | 42.9% |

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c; REALM = Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine; SBP = systolic blood pressure; TEACH-DM = Tailored Case Management for Diabetes and Hypertension

Missing data: Race = 2 (1 Intervention/1 Usual Care), Financial situation = 1 (1 Intervention/0 Usual Care), Annual Income = 52 (30 Intervention/22 Usual Care)

Only 2 study patients self-identified as having Hispanic Ethnicity, both randomized to intervention group.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Virginia (Beth) Patterson, Project Leader for the Duke PCRC, for assistance in implementing study procedures at the community study sites.

Role of the Funding Source

This project was funded by a NIDDK grant R01 DK074672 to the senior author. The sponsor had no role in designing the study; collecting, analyzing, or interpreting data; writing this manuscript; or in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ali MK, Bullard KM, Imperatore G, Barker L, Gregg EW Division of Diabetes Translation, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Characteristics associated with poor glycemic control among adults with self-reported diagnosed diabetes - national health and nutrition examination survey, United States, 2007–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61:32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013 Mar 6; Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive Blood-Glucose Control with Sulphonylureas or Insulin Compared with Conventional Treatment and Risk of Complications in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Lancet. 1998;352:837–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eastman RC, Javitt JC, Herman WH, Dasbach EJ, Copley-Merriman C, Maier W, et al. Model of complications of NIDDM. II. Analysis of the health benefits and cost-effectiveness of treating NIDDM with the goal of normoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:735–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eastman RC, Javitt JC, Herman WH, Dasbach EJ, Zbrozek AS, Dong F, et al. Model of complications of NIDDM. I. Model construction and assumptions. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:725–34. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC Diabetes Cost-effectiveness Group. Cost-effectiveness of intensive glycemic control, intensified hypertension control, and serum cholesterol level reduction for type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2002;287:2542–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed April 3, 2013];A1c Distribution Among Adults with Diagnosed Diabetes. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/a1c/A1c_dist.htm.

- 9.McFarlane SI, Jacober SJ, Winer N, Kaur J, Castro JP, Wui MA, et al. Control of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with diabetes and hypertension at urban academic medical centers. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(4):718–23. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.4.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317(7160):703–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients is affected by complications but not by intensive policies to improve blood glucose or blood pressure control (UKPDS 37). U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(7):1125–36. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geiss LS, Rolka DB, Engelgau MM. Elevated blood pressure among U.S. adults with diabetes, 1988–1994. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2002;22(1):42–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burt VL, Whelton P, Roccella EJ, Brown C, Cutler JA, Higgins M, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988–1991. Hypertension. 1995;25:305–13. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egginton JS, Ridgeway JL, Shah ND, Balasubramaniam S, Emmanuel JR, Prokop LJ, et al. Care management for Type 2 diabetes in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:72. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pimouguet C, Le Goff M, Thiébaut R, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Effectiveness of disease-management programs for improving diabetes care: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:E115–27. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duke SA, Colagiuri S, Colagiuri R. Individual patient education for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD005268. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005268.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chodosh J, Morton SC, Mojica W, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, Hilton L, et al. Meta-analysis: chronic disease self-management programs for older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(6):427–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirkman MS, Williams SR, Caffrey HH, Marrero DG. Impact of a program to improve adherence to diabetes guidelines by primary care physicians. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(11):1946–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.11.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed May 2, 2013];Practice-based Research Networks. http://pbrn.ahrq.gov/pbrn-registry/duke-primary-care-research-consortium.

- 21.Kurian AK, Cardarelli KM. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review. Ethn Dis. 2007;17(1):143–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma S, Malarcher AM, Giles WH, Myers G. Racial, ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the clustering of cardiovascular disease risk factors. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(1):43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiClemente CC, Prochaska J. Toward a comprehensive transtheoretical model of change. In: Miller WR, Healther N, editors. Treating addictive behaviors. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13(1):39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zinman B, Ruderman N, Campaigne BN, Devlin JT, Schneider SH American Diabetes Association. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26 (Suppl 1):S73–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, Brunzell JD, Chiasson JL, Garg A, et al. American Diabetes Association. Evidence-Based Nutrition Principles and Recommendations for the Treatment and Prevention of Diabetes and Related Complications. Diabetes Care. 2003;26 (Suppl 1):S51–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eraker S, Kirscht JP, Becker MH. Understanding and improving patient compliance. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1984;100:258–68. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-2-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosworth HB, Oddone EZ. A model of psychosocial and cultural antecedents of blood pressure control. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(4):236–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rimer BK, Orleans CT, Fleisher L, Cristinzio S, Resch N, Telepchak J, et al. Does tailoring matter? The impact of a tailored guide on ratings of short-term smoking-related outcomes for older smokers. Health Education Research. 1994;9:69–84. doi: 10.1093/her/9.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreuter MW, Bull FC, Clark EM, Oswald DL. Understanding how people process health information: a comparison of tailored and nontailored weight-loss materials. Health Psychol. 1999;18(5):487–94. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinberger M, Kirkman MS, Samsa GP, Shortliffe EA, Landsman PB, Cowper PA, et al. A nurse-coordinated intervention for primary care patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: impact on: glycemic control and health-related quality of life. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(2):59–66. doi: 10.1007/BF02600227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szilagyi P, Bordley C, Vann JC, Chelminski A, Kraus RM, Margolis PA, et al. Effect of patient reminder/recall interventions rates. JAMA. 2000;284(14):1820–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.14.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasson J, Gaudette C, Whaley F, Sauvigne A, Baribeasu P, Welch HG. Telephone care as a substitute for routine clinic follow-up. JAMA. 1992;267:1788–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinberger M, Tierney WM, Cowpar PA, Katz BP, Booher P. Cost-effectiveness of increased telephone contact for patients with osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;26:243–6. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benkert R, Buchholz S, Poole M. Hypertension outcomes in an urban nurse-managed center. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2001;13(2):84–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2001.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulware LE, Daumit GL, Frick KD, Minkovitz CS, Lawrence RS, Powe NR. An evidence-based review of patient-centered behavioral interventions for hypertension. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(3):221–32. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeBusk RF, West JA, Miller NH, Taylor CB. Chronic disease management: treating the patient with disease(s) vs treating disease(s) in the patient. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(22):2739–42. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.22.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeBusk RF, Houston Miller N, West JA. Diabetes case management. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(10):863. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-10-199905180-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner EH, Coleman K, Reid RJ, Phillips K, Abrams MK, Sugarman JR. The changes involved in patient-centered medical home transformation. Prim Care. 2012;39(2):241–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ullrich FA, Mackinney AC, Mueller KJ. Are primary care practices ready to become patient-centered medical homes? J Rural Health. 2013;29(2):180–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JW, Bosworth HB, Voils CI, Olsen M, Dudley T, Gribbin M, et al. How well do clinic-based blood pressure measurements agree with the mercury standard? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):647–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(S1):S12–54. doi: 10.2337/dc08-S012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(10):1644–51. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Gentry P, Orr M, Dudley T, McCant F, et al. Nurse administered telephone intervention for blood pressure control: a patient-tailored multifactorial intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rochon J. Application of GEE procedures for sample size calculations in repeated measures experiments. Statistics in Medicine. 1998;17:1643–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980730)17:14<1643::aid-sim869>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bosworth HB, Olsen MK, Grubber JM, Neary AM, Orr MM, Powers BJ, Adams MB, Svetkey LP, Reed SD, Li Y, Dolor RJ, Oddone EZ. Two self-management interventions to improve hypertension control: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):687–95. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung SH, Ahn C. Sample size estimation for GEE method for comparing slopes in repeated measures data. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:1305–15. doi: 10.1002/sim.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeger KY, Liang SL. An overview of methods for the analysis of longitudinal data. Statistics in Medicine. 1992;11:1825–39. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoerger TJ, Segal JE, Zhang P, Sorensen SW. RTI Press publication No. MR-0013-0909. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; [Accessed July 24, 2013]. Validation of the CDC-RTI Diabetes Cost-Effectiveness Model. http://www.rti.org/rtipress. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abernethy AP, Wheeler JL. True translational research: bridging the three phases of translation through data and behavior. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2011;1:26–30. doi: 10.1007/s13142-010-0013-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:S11–S66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.