Abstract

Random cell-to-cell variations in gene expression within an isogenic population can lead to transitions between alternative states of gene expression. Little is known about how these variations (noise) in natural systems affect such transitions. In Bacillus subtilis, noise in ComK, the protein that regulates competence for DNA uptake, is thought to cause cells to transition to the competent state in which genes encoding DNA uptake proteins are expressed. We demonstrate that noise in comK expression selects cells for competence and that experimental reduction of this noise decreases the number of competent cells. We also show that transitions are limited temporally by a reduction in comK transcription. These results illustrate how such stochastic transitions are regulated in a natural system and suggest that noise characteristics are subject to evolutionary forces.

Variability in gene expression within a population of genetically identical cells enables those cells to maintain a diversity of phenotypes, potentially enhancing fitness (1, 2). When the underlying gene network contains regulatory positive feedback loops, individual cells can exist in different states; some cells may, for example, live in the “off” expression state of a particular gene, whereas others are in the “on” expression state (this is an example of bistable gene expression). These stochastic fluctuations in gene expression, commonly referred to as noise, have been proposed to cause transitions between these states (3-7). We apply recently developed theories of noise (8, 9) to examine how noise influences these transitions in a natural system.

An example of bistable expression with associated stochastic transitions (10-16) involves the ability of the soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis to develop “competence” for DNA uptake as it enters stationary growth phase, potentially allowing bacteria to increase their fitness by incorporating new genetic material. The genes needed for competence are transcribed only in the presence of ComK, the master regulator of competence. comK expression is subject to positive autoregulation effected by the cooperative binding of ComK to its own promoter (Fig. 1A) (17-19), resulting in bistability (5). In one state, the positive autoregulatory loop is not activated and comK expression is low, and in the other state, the loop is activated because the level of ComK has exceeded a critical threshold and comK expression is high (13, 14).

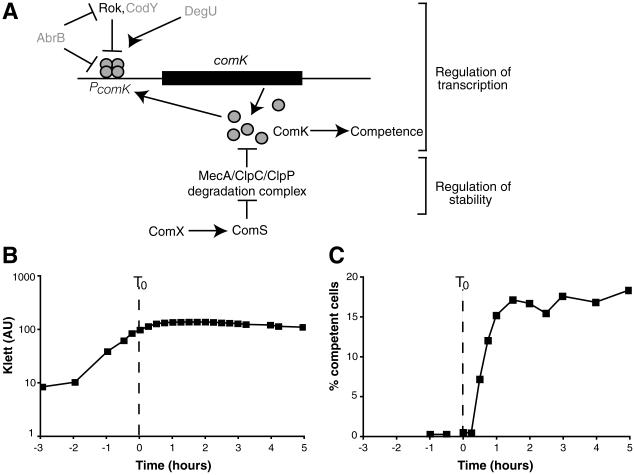

Fig. 1.

The regulation of competence in B. subtilis. (A) The comK regulatory network. Arrows and perpendiculars represent positive and negative regulation, respectively. For simplicity, factors shown in gray were not considered in our modeling. (B) The kinetics of growth in competence medium [in absorbance units (AU) measured in a Klett colorimeter]. (C) Competence development, determined microscopically with strains carrying a comK-cfp* fusion. The dashed lines in (B) and (C) represent T0.

The capacity for bistability is subject to temporal regulation. While the cells are growing exponentially, the level of ComK is kept low (i) through the action of the MecA-ClpC-ClpP protease complex, which actively degrades the ComK protein, and (ii) by transcriptional repressors such as Rok, AbrB, and CodY, precluding transitions to the competent state. Upon reaching stationary phase, the accumulation of an extracellular peptide causes an increase in the expression of the ComS protein (20) (the time of the onset of stationary phase is denoted as T0) (Fig. 1B). ComS competes with ComK for binding to the MecA-ClpC-ClpP complex (21), effectively lowering the rate of ComK degradation and allowing random fluctuations in the level of ComK to occasionally cause transitions to the competent state. Cells continue to randomly transition to competence for 2 hours, by which time (T2) transitions have ceased to occur (16) and the 15% of the cells that have become competent remain so until diluted into fresh growth medium (Fig. 1C and movie S1). In this report, we ask why cells only transition to competence for a limited duration of time and investigate the source of the fluctuations that actuate the ComK feedback loop in a minority of cells.

To understand why cells only transition to the competent state for ~2 hours during stationary phase, we examined the dynamics of comK expression in noncompetent cells. Because the level of ComK in noncompetent cells is very low, we used fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to count individual comK mRNA molecules in single cells (22–24). We achieved this level of sensitivity by using six fluorescently labeled single-stranded DNA probes, complementary to different regions of the comK mRNA (Fig. 2A, left). The hybridization of many fluorophores to individual mRNA molecules resulted in spots that are visible through a fluorescence microscope (Fig. 2, B and C).

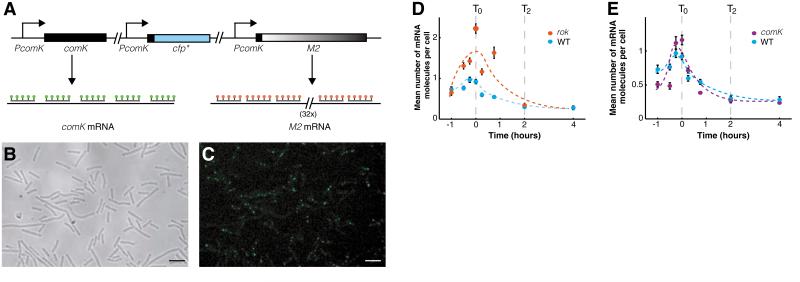

Fig. 2.

Detection of single RNA molecules (comK and comK-M2) by FISH. (A) Schematic diagram depicting the endogenous comK (left), comK-cfp* (middle), and comK-M2 (right) reporters, all controlled by the comK promoter (PcomK). Multiple specific fluorescent probes bind to each mRNA molecule [comK (green) or comK-M2 (red)], yielding distinct fluorescent signals. The comK-cfp* construct identifies competent cells. comK-cfp* designates an in-frame fusion of CFP to comK, and M2 designates the RNA with 32 repeat sequences. (B) Differential interference contrast (DIC) images and (C) pseudo-colored fluorescence images taken at T0 for the WT strain, in which the comK mRNA was hybridized to six FISH probes [C6–tetramethyl rhodamine (C6-TMR)] that bind to the comK open reading frame. Dots correspond to individual mRNA molecules. Scale bars, 4 μm. (D and E) Kinetics of the population means of mRNA molecules per noncompetent cell before and after T0 for the WT (blue circles, BD4379), the rok (red circles, BD4380), and the comK (purple circles, BD4382) strains. The WT and the rok strains (D) were hybridized to C6-TMR to detect comK mRNA molecules. The comK strain (E) was hybridized to a probe (PM2-Alexa 594) that binds to the M2 probe-binding sequence. Error bars were obtained by bootstrapping.

During late exponential and early stationary phase in the wild-type (WT) strain, the mean number of comK mRNA molecules increased from 0.7 to 1 molecules per cell at T0, at which point transitions to competence begin to occur. Thereafter, the average number of comK transcripts per noncompetent cell declined to 0.3 molecules per cell at T2 (Fig. 2, D and E).

We postulated that in early stationary phase, when the average mRNA level is elevated, the probability of transition is high because of the increased likelihood of randomly generating enough ComK to activate the positive feedback loop. Later in stationary phase, when the average is low, the probability of such an accumulation is much smaller. To test this possibility, we counted the number of comK mRNA molecules in a strain that cannot synthesize Rok, the transcriptional repressor of comK. Inactivation of rok does not change the temporal pattern of competence expression but markedly increases the fraction of competent cells (14). The average number of comK mRNA molecules per noncompetent cell in this strain was twice as large as that in the WT strain at T0 (Fig. 2D), in accordance with the larger number of competent cells observed in the rok strain (14, 25).

It is possible that the increased rate of transition to competence observed at T0 is not caused by the increased basal rate of comK transcription but is rather the cause of the increased transcription rate, because of positive feedback at the comK promoter. This possibility was eliminated by measuring the comK promoter activity in a strain lacking a functional comK gene but instead having the comK promoter drive a sequence consisting of a 50–base pair (bp) motif repeated 32 times (comK-M2). The corresponding mRNA was detected with a single-stranded DNA probe complementary to the 50-bp sequence (Fig. 2A, right). We found that the number of these mRNAs in a strain lacking an active comK gene was similar to that in the WT strain (Fig. 2E), indicating that positive feedback does not play a role in comK expression in noncompetent cells. To further verify that the comK-M2 construct had similar expression properties to those of the endogenous comK mRNA, we integrated the construct in the WTstrain and simultaneously measured the abundance of transcripts from both the endogenous comK gene and the comK-M2 gene, using differently colored fluorophores to label the two mRNAs. The mean and variance of the numbers of the two transcripts were almost identical (fig. S1).

To verify that the observed decrease in comK transcripts during stationary phase could account for a decrease in the rate of transition to competence, we constructed a simple stochastic model of the comK positive feedback loop containing the salient features of the competence network, most notably the positive feedback loop [see the supporting online material (SOM)]. The model confirmed the plausibility of our conclusion that a relatively small decrease in comK transcription can effectively end transitions to the competent state (fig. S4).

Together, these data suggest that temporal regulation of transcription controls the frequency of transitions to the competent state and that the decline in transcription of comK during stationary phase effectively defines a “window of opportunity,” which explains why cells are only able to transition to competence for a limited amount of time.

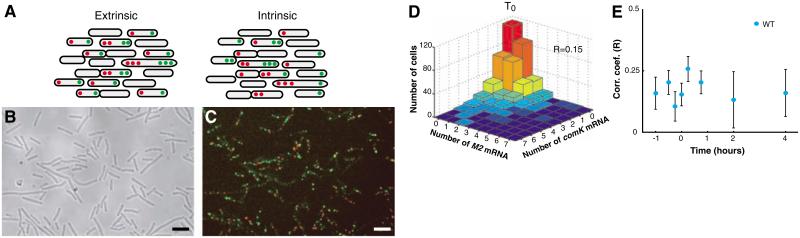

Because the cells are genetically identical and grown in a well-stirred medium, the determination of which cells are selected for competence is likely due to random cell-to-cell variations in proteins involved in competence regulation. Given its critical role in the regulation of competence, we examined the role that noise in comK plays in selecting cells for competence. Cell-to-cell variations in the numbers of comK mRNAs can come from two sources (26, 27): (i) intrinsically random events of transcription and mRNA decay (intrinsic noise) and (ii) cell-to-cell variations in regulators, polymerases, and other global factors (extrinsic noise). To gauge the relative contributions of these two types of noise to the fluctuations leading to competence, we used an approach derived from Elowitz et al.(26): counting the numbers of both endogenous comK mRNA and comK-M2 mRNA in individual cells (Fig. 3, B and C). Because any extrinsic variations should affect both genes simultaneously, correlated variations between the mRNA numbers indicate that the variations are primarily extrinsic, whereas uncor-related variations indicate an intrinsically stochastic origin for the fluctuations in mRNA numbers (Fig. 3A). In early stationary phase when most of the transitions occur, the numbers of mRNA molecules from the two species were largely uncorrelated (correlation coefficient r = 0.15 at T0) (Fig. 3, D and E). This finding indicates that intrinsically random fluctuations in comK mRNA production and degradation are likely to be a significant source of variations in ComK protein, leading to the initiation of competence (28).

Fig. 3.

Noise in comK transcription is mainly intrinsic. (A) Intrinsic and extrinsic noise were measured by detecting the mRNA from two coexpressed genes (comK and comK-M2) controlled by the comK promoter (26). Uncorrelated gene expression in individual cells is indicative of intrinsic noise. (B) DIC images and (C) pseudo-colored merged fluorescence images taken at T0 showing hybridization to comK-M2 (red) and comK (green) mRNA with the PM2-Alexa 594 and C6-TMR probes, respectively. Scale bars, 4 μm. (D) Distribution of comK and comK-M2 mRNA molecules for the WT strain (BD4379) at T0, showing weak correlations between production of the two mRNA molecules (r = 0.15). (E) Correlation coefficients throughout growth for the same strain. Error bars indicate SE.

To test the hypothesis that intrinsic noise is responsible for transitions to the competent state, we changed the noise in ComK protein production by altering the transcriptional and translational efficiency of comK. Recent studies have shown that intrinsic variations in protein expression are inversely related to the rate of transcription but are unaffected by the rate of translation (8, 9) (see SOM). Thus, increasing the rate of transcription of a gene while reducing the rate of translation by an equivalent amount would reduce noise in gene expression, despite having the same mean expression level. This reduction in noise should lead to fewer transitions to the competent state, because large fluctuations triggering activation of the positive feedback loop would become less likely (29).

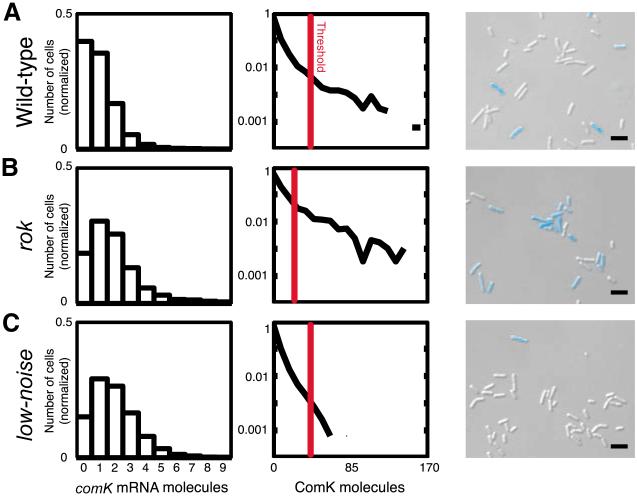

To test this prediction, we used the rok strain, which exhibits a twofold increase in comK mRNA transcription over the WT strain at T0 (Fig. 4, panels in leftmost column) (25, 30), thus decreasing the noise in ComK protein levels. To adjust the mean ComK protein level in the rok strain to approximate that of the WT strain, we changed the ATG initiation codon of comK to GTG, thereby reducing its translational efficiency (9). We verified that the mean ComK levels in the low-noise and WT strains were similar by quantifying the amount of basal ComK–cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fluorescence in bulk culture at T−0.5 and T0. Despite the slightly higher mean fluorescence in the low-noise strain, the number of its competent cells at T2 was dramatically lower than that in the WT strain, with fewer than 1% of cells being competent as compared with 15% in the WT strain (Fig. 4, panels in rightmost column). These experiments show that intrinsic noise in comK expression is responsible for the transitions to competence and that reducing noise can substantially alter the rate at which those transitions occur.

Fig. 4.

Noise reduction in comK expression lowers the percentage of competent cells. The leftmost column depicts comK mRNA distributions predicted by the model for the WT (A), rok (B), and low-noise (C) strains at T0. The middle column shows ComK protein distributions at T0 assuming a high rate of translation in the WT and rok strains [(A) and (B)] and a lowered rate of translation in the low-noise strain (C). The vertical red lines show the predicted threshold beyond which the positive autoregulatory loop of comK would be activated, resulting in competence [the threshold in the rok strain changes because of increased gene expression (see SOM)]. The rightmost column shows CFP fluorescence images from the three strains, taken at T2 and overlaid on DIC images. All three strains expressed the comK-cfp* fusion, thus fluorescing when competent. The lowest panel in the column shows a microscopic field for the low-noise strain selected to show one competent cell, although the frequency of such cells was less than 1%. Scale bars, 4 μm.

This result suggests that the noise characteristics of particular genes may be subject to evolutionary pressures. Indeed, the fact that the comK gene is weakly transcribed (12) while having a “strong” Shine-Dalgarno sequence (GGAGG–7 bp–ATG) is suggestive. For a desired final percentage of competent cells, there must be a set fraction of cells with the level of ComK above a particular threshold, achievable either by having a basal ComK distribution with a low mean and a large variance or by having a higher mean with a lower variance. Because of the metabolic cost of maintaining a larger mean number of proteins, it is plausible that cells would opt for the former option rather than the latter, as appears to be the case for comK.

The temporal regulation of comK transcription during stationary phase defines when transitions to the competent state may occur (the window of opportunity), and intrinsic noise in comK expression defines the rate at which cells become competent. Our results imply that noise properties are subject to evolutionary forces and suggest how cells might alter those rates to increase fitness. Because noise has been implicated in a variety of cellular behaviors, such knowledge can help both in the understanding of natural regulatory networks (7, 31) and in the synthesis of artificial networks (4, 32).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM 57720.

A.R. was supported by NIH grant GM 070357 and by NSF postdoctoral fellowship DMS-0603392.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1140818/DC1

Materials and Methods

SOM Text

Figs. S1 to S7

Tables S1 to S3

References

Movie S1

References and Notes

- 1.Raser JM, O’Shea EK. Science. 2004;304:1811. doi: 10.1126/science.1098641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaern M, Elston TC, Blake WJ, Collins JJ. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:451. doi: 10.1038/nrg1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Lim HN, Shraiman BI, van Oudenaarden A. Nature. 2004;427:737. doi: 10.1038/nature02298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Nature. 2000;403:339. doi: 10.1038/35002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Isaacs FJ, Hasty J, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:7714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1332628100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becskei A, Seraphin B, Serrano L. EMBO J. 2001;20:2528. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acar M, Becskei A, van Oudenaarden A. Nature. 2005;435:228. doi: 10.1038/nature03524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thattai M, van Oudenaarden A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:8614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151588598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozbudak EM, Thattai M, Kurtser I, Grossman AD, van Oudenaarden A. Nat. Genet. 2002;31:69. doi: 10.1038/ng869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubnau D, Losick R. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smits WK, Kuipers OP, Veening JW. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:259. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suel GM, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Liberman LM, Elowitz MB. Nature. 2006;440:545. doi: 10.1038/nature04588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smits WK, et al. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maamar H, Dubnau D. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;56:615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suel GM, Kulkarni RP, Dworkin J, Garcia-Ojalvo J, Elowitz MB. Science. 2007;315:1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1137455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leisner M, Stingl K, Radler JO, Maier B. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Sinderen D, Venema G. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:5762. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5762-5770.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Sinderen D, et al. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;15:455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamoen LW, Van Werkhoven AF, Bijlsma JJE, Dubnau D, Venema G. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1539. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn J, Kong L, Dubnau D. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:5753. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5753-5761.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prepiak P, Dubnau D. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:639. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodriguez AJ, Shenoy SM, Singer RH, Condeelis J. J. Cell Biol. 2006;175:67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raj A, Peskin CS, Tranchina D, Vargas DY, Tyagi S. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Femino AM, Fay FS, Fogarty K, Singer RH. Science. 1998;280:585. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoa TT, Tortosa P, Albano M, Dubnau D. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Science. 2002;297:1183. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swain PS, Elowitz MB, Siggia ED. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:12795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162041399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. It is conceivable that fluctuations in the posttranslational control of ComK levels could introduce some extrinsic variations in ComK, but the fact that comS is transcribed equally in competent and noncompetent cells (20) argues against this possibility. It is also possible that the small extrinsic component of the noise in transcription could be magnified at the protein level if the ComK protein degradation rate was extremely low; however, stochastic simulations show that this is very unlikely in our case (fig. S7; see SOM for further discussion).

- 29. We verified this intuitive picture by using computer simulations of the complete model referred to previously (fig. S5). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albano M, et al. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:2010. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.6.2010-2019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balaban NQ, Merrin J, Chait R, Kowalik L, Leibler S. Science. 2004;305:1622. doi: 10.1126/science.1099390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elowitz MB, Leibler S. Nature. 2000;403:335. doi: 10.1038/35002125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. We acknowledge the assistance of S. Tyagi, S. Marras, and D. Gold for the gift of the repeat sequence plasmid, for the use of their spectrophotometer and microscope, and for the preparation of fluorescent probes. We also acknowledge D. Rudner for the gift of the codon-optimized CFP and C. S. Peskin for valuable discussions. We also thank S. Tyagi, A. van Oudenaarden, J. Gore, J. Tsang, M. B. Elowitz, G. M. Suel, and P. Mehta for comments on the manuscript, as well as an anonymous reviewer for insightful comments.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.