Abstract

Chemokines are the inflammatory mediators that modulate liver fibrosis, a common feature of chronic inflammatory liver diseases. CX3CL1/fractalkine is a membrane-associated chemokine that requires step processing for chemotactic activity and has been recently implicated in liver disease. Here, we investigated the potential shedding activities involved in the release of the soluble chemotactic peptides from CX3CL1 in the injured liver. We showed an increased expression of the sheddases ADAM10 and ADAM17 in patients with chronic liver diseases that was associated with the severity of liver fibrosis. We demonstrated that hepatic stellate cells (HSC) were an important source of ADAM10 and ADAM17 and that treatment with the inflammatory cytokine inter-feron-γ induced the expression of CX3CL1 and release of soluble peptides. This release was inhibited by the metalloproteinase inhibitor batimastat; however, ADAM10/ADAM17 inhibitor GW280264X only partially affected shedding activity. By using selective tissue metalloprotease inhibitors and overexpression analyses, we showed that CX3CL1 was mainly processed by matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, a metalloprotease highly expressed by HSC. We further demonstrated that the CX3CL1 soluble peptides released from stimulated HSC induced the activation of the CX3CR1-dependent signalling pathway and promoted chemoattraction of monocytes in vitro. We conclude that ADAM10, ADAM17 and MMP-2 synthesized by activated HSC mediate CX3CL1 shedding and release of chemotactic peptides, thereby facilitating recruitment of inflammatory cells and paracrine stimulation of HSC in chronic liver diseases.

Keywords: chemokines, shedding, liver fibrosis, hepatic stellate cells

Introduction

The liver response to chronic injury is characterized by wound-healing processes including inflammation and excessive deposition of extracellular matrix which leads to fibrosis/cirrhosis [1], the strongest risk for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). During these processes, chemokines, a family of chemotactic cytokines, have been shown to play a critical role in the recruitment of inflammatory cells from blood stream and also in fibrogenesis [2, 3]. Based on their conserved arrangement of the cysteine residues, chemokines are classified into four subfamilies C, CC, CXC and CX3C chemokines [4]. Fractalkine, also named CX3CL1, is the unique member of the CX3C class and exists in both soluble peptides and membrane-anchored forms. Thus, the chemokine domain is linked to a mucin-rich, transmembrane stalk and allows CX3CL1 to function as an adhesion molecule [5] whereas the proteolytic release of chemokine domain generate soluble chemoattractive molecule [6, 7]. CX3CL1 binds to the unique CX3CR1 receptor, a cell surface marker for NK cells, T cells, monocytes [8] which is also expressed by smooth muscle cells [9]. The importance of CX3CL1–CX3CR1 pathway during liver injuries has been suggested by the up-regulation of CX3CL1 and its receptor in acute and chronic liver diseases involving both inflammatory and epithelial cells [10, 11]. More recently, the potential modulation of host immune response by CX3CL1 and its receptor has been associated with improved survival of liver tumour-bearing mouse [12] and better prognosis in patients with HCC [13]. CX3CR1 was associated with inflammatory cells and regenerative epithelial cells within bile ductules. Taken together these observations suggest the involvement of CX3CL1/CX3CR1 pathway in chronic liver diseases.

The CX3CL1 activity in the tissues has been mainly associated with its potential chemotactism property; however, the mechanisms involved in release of chemotactic CX3CL1 peptides are few documented in vivo. Several studies showed the implication of zinc-dependent family of metalloproteinase in shedding, a limited proteolysis process of transmembrane proteins at cell surface. Among them, the disintegrin and metalloproteinase family proteins (ADAM), also termed sheddases, are involved in the cleavage of various cytokines, growth factors, receptors and adhesion molecules [14]. Shedding of CX3CL1 has been attributed to ADAM10 and ADAM17 (tumour necrosis factor-α-converting enzyme) activities through constitutive and induced pathways, respectively [6, 7, 15].

Increases in matrix metalloproteinase activities were previously reported during liver injury and we demonstrated that extracellular matrix remodelling was associated with fibrosis progression [16]. As main source of matrix and proteases, the role of the profibrogenic hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) in this process has been well documented [17]. More recently, increased expression of members of ADAM family, including ADAM9, ADAM12 and ADAM17 was reported in patients with chronic liver diseases and expressed by the activated HSC [18–21]. In the present study, we investigated whether HSCs are involved in CX3CL1 shedding during liver injury. We showed an overexpression of both ADAM10 and ADAM17 in patients with chronic liver diseases that was associated with fibrosis grade. In addition activated HSC are an important source of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in the liver. We further found that stimulation of cultured HSC by the pro-inflammatory cytokine interferon (IFN)-γ dramatically induced the expression of CX3CL1 and the matrix metalloprotease dependent release of its soluble form. Finally, we demonstrated for the first time that in addition to ADAM10 and ADAM17, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 a protease highly secreted by HSC [22, 23] is involved in the release of CX3CL1 chemotactic peptides suggesting a pivotal role of HSC in regulating autocrine and paracrine activity of CX3CL1 during liver injury.

Material and methods

Sample tissue

Fibrotic liver tissues were non-tumoral part of livers obtained from 27 patients undergoing partial hepatectomy for resection of a primary HCC. Controls were 10 histologically normal liver samples, obtained from the non-tumoral parts of livers complicated with colorectal metastases as previously described [16]. After macroscopic examination by a pathologist, representative samples were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin for histopathological routine diagnosis; a part of the fresh material was snap frozen in isopentane cooled in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. The histological stages of fibrosis were graded according to the Métavir score: F1, portal fibrosis without septa; F2, portal fibrosis with rare septa; F3 numerous septa without cirrhosis and F4 cirrhosis. Access to this material was in agreement with French laws and satisfied the requirements of the local Ethics Committee.

Cell culture and transfection

Human hepatocytes, HSCs and an enriched fraction in liver macrophage cells were prepared from histologically normal tissues from patients undergoing hepatic resection for liver metastases as previously described [20]. Briefly, hepatocytes were isolated using the two-step collagenase perfusion method and human-activated HSC were purified by a single-step density gradient centrifugation with Nycodenz from sinusoidal cells enriched supernatant after hepatocyte isolation. An enriched fraction of liver macrophages was isolated by using CD14-Dynabeads (Dynal, A.S. Oslo, Norway). HSC were serum-starved and treated with IFN-γ (1 μg/ml) for different times from 0 to 24 hrs. In some experiments, HSC were stimulated with either 0.1 μM phorbol 12-Myristate 13-acetate (PMA), or 10 μM concanavalin A (ConA) (Sigma, St Quentin, France) and treated with metalloprotease inhibitors including 0–50 nM recombinant tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TMP1), TIMP2, TIMP3 (R&D Systems, Europe, Lille, France), 10 μM BB94 (Batimastat from British Biotech, Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Oxford, UK) and 3 μM GW280264X (Dr. A. Ludwig, Institute of Biochemistry, Kiel, Germany). The human embryonic kidney (HEK) cell line 293T and the HEK-CX3CR1 clone cells (Dr C. Combadierre, Hôpital Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France) were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum, 10 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and geneticin (G418) for HEK-CX3CR1 clone to maintain selection. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and THP1 monocytic cells were maintained in Ham's F12 medium and RPMI medium, respectively. CX3CR1 blocking antibody (Torrey Pines Biolabs, Houston, TX USA) was incubated with cells 30 min. before addition of conditioned media from HSC to 293T cells or before chemotaxis assay on THP1 cells. CHO were transfected using Lipofectamin (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Expression vectors for the constitutive active MMP-2 (App MMP-2) and the inactive-mutant MMP-2 (pp E375A MMP-2) were a gift from Dr. C Overall (Vancouver, Canada).

Relative quantification of mRNA by real-time PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR was performed as previously described [20]. Primer pairs for target genes were; ADAM10, sense: 5′-CATTGCTGAAT-GATTGTGG-3′; anti-sense: 5′-GTGCCTGGAAGTGGTTTAGG-3′, MMP-2 sense 5′-TAGTGAGTGGCCGTGTTTGC-3′, anti-sense 5′-AGGGAGCAGA-GATTCGGACTT-3′; ADAM17, sense 5′-CCATGAAGTGTTCCGATAGAT-3′, anti-sense: 5′-ACCTGAAGAGCTTGTTCATCG-3′; CX3CL1, sense: 5′-GGAAAGGGGAAGTTGTAGGC-3′, anti-sense: 5′-AATCCAAGGGAGAGGT-GAGC-3′; CX3CR1, sense 5′-TCCCTTCCCATCTGCTCAGGA C-3′, anti-sense: 5′-ACAATGTCGCCCAAATAACAGG-3′; 18S, sense: 5′-CGCCGCTA-GAGGTGAAATTC-3′, anti-sense : 5′-TTGGCAAATGCTTTCGCTC-3′. Using the comparative Ct method, the amount of target sequence in unknown samples normalized to the 18S reference, was expressed relative to a calibrator (mean of control in our assay).

Immunostaining and imaging

Five-micrometer-thick frozen sections from liver tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and treated for 30 min. in 0.3% H2O2 to inactivate endogenous peroxidase. Sections were then blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin-phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (w/v) and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, mouse α-sma (Sigma Aldrich, St Quentin, France) or mouse CX3CL1 (RetD system) or isotype controls. After washing, sections were incubated for 1 hr at room temperature with secondary antibodies. The bound antibodies were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies antimouse (Pierce Rockford, IL, USA). All sections were counterstained with haematoxylin.

To detect CX3CL1 in HSC, cells were plated on Permanox Lab-Tek chamber slides supporting cell attachment (NUNC, Rochester, NY, USA) for 24 hrs. Cells were serum starved before treatment with IFN-γ for 24 hrs and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. When indicated, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% triton X100. Cells were further incubated with mouse CX3CL1 antibodies (R&D Systems), mouse FITC-conjugated α-smooth actin antibodies (Sigma Aldrich) or mouse isotype controls (IgG1 and IgG2a, respectively) and then with TRITC-conjugated antimouse IgG antibodies. The slides were washed, mounted and viewed on the automated microscope Leica DMRXA2 equipped with Photometrics CoolSnapES N&B camera driven by MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, PA, USA).

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE, West Harrow, UK). The blot was incubated for 1 hr in Tris buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% non-fat dry milk and further incubated for 1 hr with anti-CX3CL1 (R&D Systems) or anti-P-p44/p42 MAPK (Thr 202/Tyr 204)(Cell Signaling, Boston, MA, USA) antibodies. The bound antibodies were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies to goat (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or mouse (BioRad, Ivry, France) IgG using an enhanced chemilumi-nescence system (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Monocyte chemotaxis assay

THP1 cells were harvested and washed in serum-free RPMI1640. Cells were then stained with 2′,7′-Bis- (2-Carboxyethyl)-5- (And-6)- carboxyfluorescein (BCECF) for 15 min. at 37°C and loaded in a total volume of 300 μl into the upper compartment of a chemotaxis chamber (Fluoroblok, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). HSC conditioned media were loaded in the lower compartment. The chemotaxis chamber was incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 1 hr. Fluorescent migrating cells were counted using a Leica DMIRBE inverted microscope. Cell numbers were counted in six different microscopic fields and chemotactic index was expressed as cell numbers/mm2.

Quantification of soluble CX3CL1 by ELISA

HSC conditioned media were clarified by centrifugation at 800 ×g for 5 min. at 4°C. Soluble CX3CL1 levels were quantified by using a commercially available ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems).

Zymography

Zymographic analyses were performed on conditioned medium from HSC culture as previously described [24].

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± S.D. The significance of the differences between means was evaluated with the Mann-Whitney U test. Spearman rank order correlation coefficients were used to express the association between the different variables within the study groups. Data were analysed using the Statistica release 4.3B software package (StatSoft, Inc., Maison Alfort, France).

Results

Up-regulation of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in chronic liver disease: association with fibrosis grade and HSCs

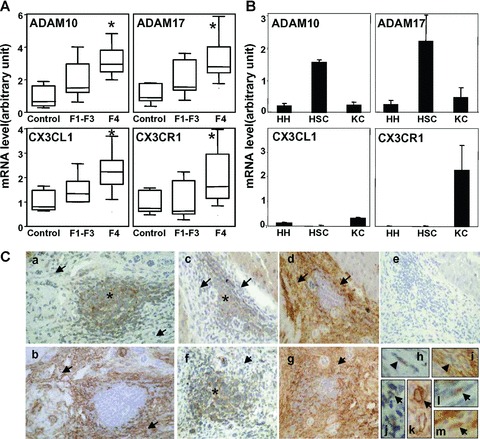

To investigate the potential role of ADAM activity in CX3CL1/CX3CR1 pathway in injured liver, we first analysed the steady-state mRNA levels of the two sheddases ADAM10 and ADAM17 involved in CX3CL1 cleavage, in liver tissue samples from patients with chronic liver disease. Patients were 24 men and 3 women with a median age of 59 years (range: 45–75) including four patients positive for hepatitis virus C, six for hepatitis virus B and nine for alcohol abuse. Twenty patients were diagnosed with cirrhosis (F4) and 7 with fibrosis (F1-F3) with a necroinflammatory activity ranging from A1 to A3 according to the METAVIR score. As shown in Fig. 1A, expression of ADAM10 and ADAM17 was increased in tissue samples with fibrosis compared to control liver. Interestingly, the observed increase in mRNA expression for ADAM10, ADAM17 was associated with the grade of fibrosis since all genes were up-regulated in F4 compared with the F1-F3 grades. Spearman rank order correlation studies showed that ADAM10 and ADAM17 mRNA levels were highly correlated in liver samples (r= 0.90, P< 0.001). Similarly, increased expression of CX3CL1 and its receptor CX3CR1 was observed in fibrosis tissue samples when compared with normal livers.

Fig. 1.

Association of ADAM10 and ADAM17 mRNA expression with fibrosis and activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). (A) ADAM10, ADAM17, CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 mRNA were determined by real-time PCR in fibrotic livers (F1-F2-F3), cirrhotic livers (F4) and normal livers (Control). Data are shown as mean ± S.D. from a representative experiment. (B) ADAM10, ADAM17, CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 mRNA expression was analysed in cultured human hepatocytes (HH), isolated cultured human HSCs and enriched fraction of liver Kupffer cells (KC). (C) Localization of CX3CL1 and α-SMA in fibrotic liver tissues from patients with hepatocellular carcinomas: a, c, f, h, j and l: CX3CL1; b, d, g, i, k, and m: α-SMA. The ‘inflammatory cell islet’ staining is identified by asterisk and a-SMA+ cells by arrows. Specific antibodies were omitted and replaced by IgG isotype antibodies in negative control serial sections (e) and immunoperoxidase was counterstained with haema-toxylin. (Original magnification: [a, b], 100; [c-f, g], 25; [h-l], 800).

We subsequently showed that culture of isolated HSCs, resulting in activation which mimics HSC response to liver injury, highly expressed ADAM10 and ADAM17 compared with hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (Fig. 1B). During the course of the analysis we investigated CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 expression and we identified Kuppfer cells as the major source of CX3CR1 whereas CX3CL1 was weakly expressed in isolated liver cells from healthy livers. Next, we searched for CX3CL1 distribution in fibrotic livers by using immuno-histochemistry analyses (Fig. 1C). CX3CL1 staining was associated with mononuclear inflammatory cell infiltrates but also with surrounding a-smooth actin positive cells, a major marker of activated HSC in fibrotic liver. Taken together our data suggest that activated HSCs are an important source of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in injured liver and that α-SMA+ cells might contribute to CX3CL1 expression.

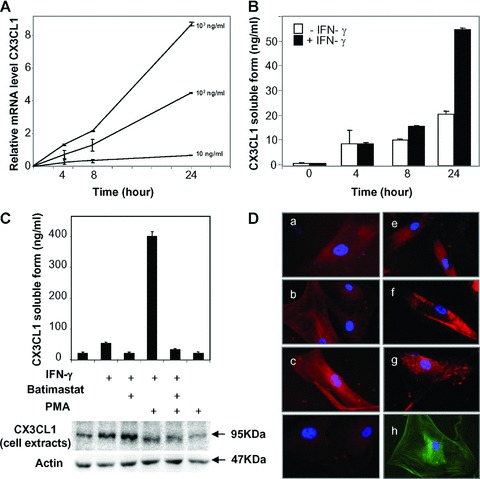

IFN-γ stimulation induces CX3CL1 expression in HSCs

According to our observation in tissues, we suggested that stimulation of cultured HSC by pro-inflammatory cytokines mimicking the inflammatory environment might stimulated CX3CL1 synthesis in HSC. To test this, cells were treated with increasing concentration of IFN-γ and CX3CL1 expression was investigated by using real-time PCR. IFN-γ induced a time and dose-dependent increase in CX3CL1 mRNA levels in HSC demonstrating that these cells might be a cellular source of CX3CL1 during chronic liver injury (Fig. 2A). The increase in CX3CL1 expression was associated with release of soluble CX3CL1 in the HSC supernatant suggesting constitutive proteolysis of the mature CX3CL1 forms (Fig. 2B). ADAM10 has been previously involved in the constitutive cleavage of CX3CL1 [15] whereas ADAM17 mediated the PMA inducible shedding of CX3CL1 [6, 7]. We showed that cultured human HSC expressed both ADAM10 and ADAM17 (Fig. 1B) and that IFN-γ treatment of cells did not modify the expression level of ADAMs (Supporting Information data S1). IFN-γ treatment of human HSC induced release of soluble CX3CL1 that was dramatically enhanced when cells were further stimulated by PMA (Fig. 2C). Constitutive and PMA-dependent release of soluble CX3CL1 from IFN-γ-treated cells were inhibited by the broad spectrum MMP inhibitor, batimastat. In addition, CX3CL1 proteins in cell extracts strongly accumulated upon batimastat treatment whereas PMA stimulation induced CX3CL1 diminution in cell extracts (Fig. 2C). Our data suggest that IFN-γ induces CX3CL1 expression that is weakly cleaved by constitutive sheddase activity and strongly cleaved by a PMA-inducible sheddase activity. To further explore CX3CL1 shedding process in HSC, we performed immunocyto-chemical studies for CX3CL1 in IFN-γ stimulated cells in presence or absence of batimastat (Fig. 2D). Because shedding activity has been proposed as a cell surface phenomenon, we examined the distribution of CX3CL1 without and with cell permeabilization. In subconfluent culture, CX3CL1 staining was diffuse in permeabilized cells without significant change upon treatment. When cells were not permeabilized, we showed a slight increase in CX3CL1 staining after IFN-γ treatment which was enhanced in presence of batimastat suggesting that inhibition of MMP-dependent shedding activities led to accumulation of proteins at cell surface. In addition CX3CL1 labelling displayed patched areas in batimastat-treated cells suggesting specific membrane localization. Taken together our data suggested that IFN-γ induced CX3CL1 expression in HSC and PMA treatment stimulated protein release through a metalloprotease-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 2.

Effect of IFN-γ on CX3CL1 expression in human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). (A) CX3CL1 mRNA was determined by real-time PCR in human cultured HSC stimulated with increasing concentrations of IFN-γ for the indicated periods. (B) Generation of soluble CX3CL1 was measured by ELISA in conditioned media from human HSC treated (black) or untreated (white) with IFN-γ (1 μg/ml) for the indicate periods. For A and B, bars represented means ± S.D. of triplicate measurements and are representative of two separate experiments. (C) HSC treated or not treated with 1 (μg/ml IFN-γ (overnight) were further stimulated with 100 ng/ml PMA or left unstimulated, in presence or absence of the MMP inhibitor batimastat. Soluble CX3CL1 was quantified by ELISA in conditioned media (top panel) and proteins from cell extracts were analysed by Western blot (bottom panel). (D) Immunolocalization of CX3CL1 in human HSC unstimulated (a, e) or stimulated (b, c, f, g) with IFN-γ in absence (a, b, e, f) or presence (c, g) of batimastat. Cells were permabilized (a-c) or unpermeabilized (e-g). Controls included incubation with IgG isotypes (d) and localization of α-SMA proteins (h). Representative data from three independent experiments are shown.

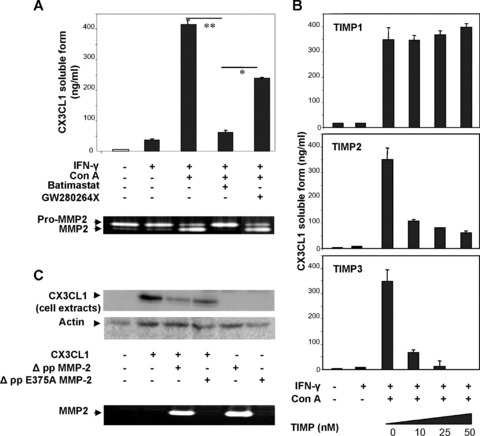

Involvement of MMP-2 in CX3CL1 cleavage from IFN-γ stimulated HSC

To further characterize the potential involvement of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in CX3CL1 shedding, we tested the effect of the hydroxamate GW280264X, an inhibitor of ADAM10 and ADAM17 [15]. When compared with batimastat, we always observed that the hydroxamate GW280264X only partially inhibited the release of soluble CX3CL1 from IFN-γ stimulated cells in presence of PMA, suggesting that other proteases are implicated (supplementary data S2). In absence of PMA, the low amount of constitutive shedding of CX3CL1 did not permit to show significant difference between the two inhibitors. Because HSC is the major cellular source of MMP-2 in injured liver and its activity is inducible by PMA [25], we suggested that MMP-2 was potentially involved in CX3CL1 shedding. IFN-γ-treated HSC that secrete latent MMP-2 form were stimulated by the most widely studied inducer of MMP-2 activation, ConA. Treatment with ConA induced an increase in soluble CX3CL1 release and this effect was inhibited by adding batimastat whereas GW280264X only induced partial inhibition (Fig. 3A). Accordingly, CX3CL1 shedding was associated with the activation of MMP-2 as demonstrated by using zymography analysis. Under experimental condition, IFN-γ treatment did not modify MMP-2 expression in cultured HSC (supplementary data S1). We further tested the ability of the natural metalloproteinase inhibitors TIMP1, TIMP2 and TIMP3 to block CX3CL1 cleavage in ConA-treated HSC (Fig. 3B). As demonstrated by analyses of the conditioned media using ELISA, TIMP2 and TIMP3 blocked specifically the release of CX3CL1 from HSC. TIMP1, however, did not block the generation of soluble CX3CL1. Both TIMP1 and TIMP2 have been shown to inhibit numerous MMPs; however TIMP1 has no effect on MMP-14, the main activator of MMP-2 and blocks ADAM10 [26]. In contrast, TIMP3 have been reported to inhibit numerous ADAM members including ADAM12–17-19–10, ADAMTS 4–5 and only two gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9. Our data suggested that MMP-2 might cleave CX3CL1 from IFN-γ stimulated human HSC. To further confirm the potential implication of MMP-2 in CX3CL1 processing, we investigated the release of soluble CX3CL1 in conditioned media from CHO cells co-trans-fected with MMP-2 and CX3CL1 expression vectors. The expression of the constitutive active MMP-2 (AppMMP-2) led to the disappearance of mature CX3CL1 forms in cells whereas the inactive-mutant MMP-2 (pp E375A MMP-2) did not (Fig. 3C). Taken together our data suggested that activated MMP-2 from HSC might modulate the activity of CX3CL1 during chronic liver injury.

Fig. 3.

Involvement of MMP-2 in CX3CL1 cleavage. (A) IFN-γ-stimulated human HSC were treated with ConA in presence or absence of chemical inhibitors either directed against MMP, batimastat, or ADAM10 and ADAM17, GW280264X. Soluble CX3CL1 was measured in conditioned media (top panel) and MMP-2 activity was analysed by zymography (bottom panel). (B) Soluble CX3CL1 was quantified in conditioned media from IFN-γ-stimulated human HSC, treated with ConA in presence or absence of physiological inhibitors of metalloproteinase, TIMP1 (up panel), TIMP2 (middle panel) and TIMP3 (bottom panel). (C) CHO cells were transfected with CX3CL1 and constitutive active MMP-2 or catalytic deficient mutant of MMP-2. CX3CL1 was analysed by Western blot in cell extracts (top panel). MMP-2 activity was controlled by zymography (bottom panel). Representative data from three independent experiments are shown.

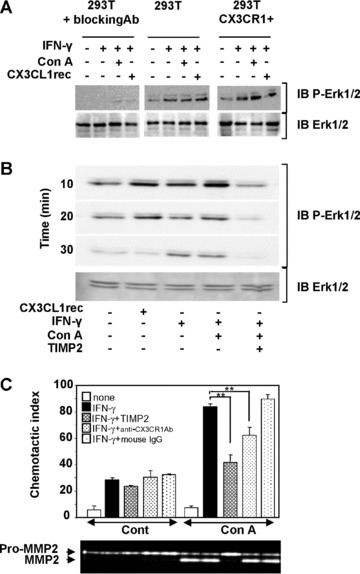

Biological activity of CX3CL1 derived from HSCs

To evaluate the functional role of the soluble CX3CL1 forms derived from HSC, we investigated the potential of conditioned media from IFN-γ stimulated HSC to induce ERK-dependent signalling pathway in HEK293T cells [27]. The involvement of CX3CL1/CX3CR1 pathway was further validated by using either blocking antibodies against CX3CR1 or CX3CR1-overexpressing HEK293T cell line (Fig. 4A). As positive control, treatment of the cells with recombinant CX3CL1 induced activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 suggesting that these cells responded to CX3CL1-mediated signalling pathway. The conditioned media from IFN-γ-stimulated HSC induced the activation of ERK1/2 in 293T cells. When HSC were co-stimulated by ConA, conditioned media enhanced ERK1/2 activation in wild-type 293T cells and induced an increase in CX3CR1 overexpressing 293T cells. In contrast, the ERK1/2 activation was totally inhibited by incubation of cells with blocking anti-CX3CR1 antibodies in both conditions. In order to demonstrate the implication of MMP-2 in the CX3CR1-dependent activation of ERK1/2 pathway, CX3CR1-transfected 293T cells were incubated with conditioned media from HSC treated with or without ConA to activate MMP-2 in presence or absence of TIMP2. When conditioned media from IFN-γ-stimulated HSC were used, ERK1/2 activation was detected with a prolonged effect at 30 min. compared with direct effect of recombinant CX3CL1 (Fig. 4B). This effect was enhanced in presence of ConA that induces MMP-2 activation and totally inhibited in presence of the inhibitor, TIMP2. Our data suggested involvement of metallo-protease activity in activation of ERK1/2 pathway induced by HSC conditioned media in CX3CR1 expressing 293T cells. In order to explore the functional relevance of CX3CL1 in HSC-conditioned media, we next investigated its effect on the chemotactic activity using the human monocyte cell line, THP-1 (Fig. 4C). Conditioned media from IFN-γ-treated HSC stimulated with ConA increased migration of THP1 cells. When HSC were incubated with TIMP2 or CX3CR1 blocking antibodies added to conditioned media, the effect on chemotactic activity was reduced suggesting involvement of MMP-2 in CX3CR1-dependent THP1 migration. We have previously demonstrated that activation of MMP-2 occurred when HSC are seeded on type I collagen, the main component of extracellular matrix in fibrotic liver [28]. Similar to ConA effect, we showed that seeding HSC on type I collagen induced increase in CX3CL1 release (Fig. 5A) and THP1 migration (Fig. 5B) suggesting that fibrotic context might favour the role of HSC in providing chemotactic peptides and further facilitate the recruitment of inflammatory cells.

Fig. 4.

Biological activity of the MMP-2-dependent release of soluble CX3CL1 peptides. (A) Conditioned media from human cultured HSC stimulated by IFN-γ in presence or absence of ConA were added to either wild-type 293T cells or CX3CR1 overexpressing 293T cells or 293T cells pre-incubated with blocking CX3CR1 antibodies, for 30 min. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was measured by Western blot analysis of total cell extracts. CX3CL1 recombinant protein (recCX3CL1) was used as positive control. (B) Conditioned media from HSC stimulated by IFN-γ in presence or absence of ConA and TIMP2 were added to CX3CR1 overexpressing cells. Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in cell extracts was analysed by Western blot for the indicated periods. (C) Conditioned media from HSC stimulated by IFN-γ were assayed for chemotactic activity on human monocyte cell line, THP1. HSC were treated with ConA to induce MMP-2 activation and were further incubated in presence or absence of TIMP2. When indicated, conditioned media were pre-incubated with 10 μg/ml blocking mAb to CX3CR1 or were left untreated for 30 min. before THP1 chemotaxis assays (IgG isotype were used as control). Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments and zymography analysis is representative of one experiment.

Fig. 5.

Effect of type I collagen on soluble CX3CL1 release from HSC. HSC were seeded on type I Collagen and further stimulated by IFN-γ. Conditioned media were removed and used for: (A) measure of CX3CL1 release by ELISA (data were normalized with total cell protein amount); (B) THP1 chemotaxis assay and (C) zymography analyses. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments and zymography analysis is representative of one experiment.

Discussion

Several recent studies suggested that the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis plays an important role during liver injury mainly by providing a chemotactic gradient to recruit immune cells. As a consequence host immune response and tissue repair are facilitated but also contribute to fibrosis in chronic liver disease. The critical point for a potential implication of CX3CL1 resides in the processing step of the membrane-linked CX3CL1 form towards a soluble chemokine peptide. Here, we showed that the proteases ADAM10 and ADAM17 which were previously demonstrated to cleave CX3CL1 were up-regulated during the fibrosis process in chronic liver disease and were expressed by the profibrogenic cells, HSC. Furthermore we demonstrated for the first time that the metalloproteinase MMP-2 secreted by these cells is also involved in the shedding of CX3CL1.

To date the proteases implicated in shedding activities belong exclusively to the zinc-metzincin family of metalloproteinases and previous reports demonstrated the involvement of ADAM10 [15] and ADAM17 [6, 7] in constitutive and PMA-inducible shedding of CX3CL1, respectively. In the liver, the expression and distribution of MMP have been extensively studied [29]; however, very few information are available on the members of ADAM family. We previously reported the increased expression of ADAM9 and ADAM12 in patients with HCC [20] and ADAM17 expression was associated with tumour differentiation [18]. More recently up-reg-ulation of ADAM8–9-12 and -28 was also reported in chronic liver diseases [21]. In the present study, we investigated the expression of both ADAM10 and ADAM17 and the CX3CR1/CX3CL1 system in chronic liver diseases. According to previous report, the CX3CL1 and CX3CR1 mRNA levels were increased in injured livers [10, 11, 13] and we now observed that ADAM10 and ADAM17 mRNA levels were also up-regulated. Interestingly, increased expression of ADAMs was associated with the severity of fibrosis and highly expressed by cultured human HSC. Upon chronic damage of liver tissue, HSC become activated and differentiate into a fibroblast-like phenotype which synthesized matrix components and are the main source of another metalloproteinase, MMP-2 [24, 30, 31]. Unlike ADAMs, CX3CR1 expression was mainly recovered in our macrophage-enriched fraction in accordance with several studies that showed CX3CR1 expression on infiltrating mononuclear cells and also on biliary epithelial cells and hepatic blood vessels [10, 11]. More recently CX3CR1 was observed in HSC [32]; however in our hands, CX3CR1 mRNA levels in HSC remain very low compared with the macrophage fraction suggesting a modest contribution of autocrine pathway. Unexpectedly, immunohistochem-istry studies in liver tissue sections showed numerous patched distributions of CX3CL1 associated with both monocyte infiltrates and surrounding cells highly positive for α-smooth-actin, the main marker of activated HSCs. We suggested that inflammatory stimuli may stimulate CX3CL1 expression in HSC as inflammatory cytokines were previously reported to induce expression of another chemokine, MCP1 in HSC [2]. Here we have shown that stimulation by IFN-γ induced CX3CL1 expression and further constitutive and PMA-inducible release of CX3CL1 soluble forms from HSC. According to the literature, we thought to evaluate the involvement of the two putative sheddases ADAM10 and ADAM17 that were highly expressed in our cells. Although the IFN-γ-dependent down-regulation of ADAM17 in rat HSC was recently reported by using a differential proteomic assay [19], the expression levels of ADAM10 and ADAM17 were not modified by IFN-γ treatment in human cultured HSC. Surprisingly, the specific inhibitor hydroxamate GW280264X that blocks ADAM10 as well as ADAM17 [15] partially affected the cleavage of CX3CL1 that was totally inhibited by batimastat suggesting the implication of another metalloprotease. Based on our previous studies [24, 28], we investigated the involvement of MMP-2 and we demonstrated the association between release of the CX3CL1 soluble forms and MMP-2 activity in conditioned media from HSC. We showed further evidence for MMP-2 implication in CX3CL1 shedding by using CHO cells transfected with CX3CL1 expression vector and constitutive active MMP-2. In accordance with our results, CX3CL1 was recently identified as a putative substrate for MMP-2 by using a high throughput iTRAQ proteomic approach [33] and identification of numerous cell surface substrates suggests that MMP-2 acts as a sheddase [34]. Moreover Dean et al. identified cleavage sites for MMP-2 generating soluble forms containing the chemotactic peptides [34]. Accordingly we showed that activation of MMP-2 induced the release of CX3CL1 soluble peptides triggering CX3CR1-dependent signalling cascade and promoting monocytes chemotactism. Close interaction between HSC and immune cells have been widely documented and suggested to play a critical role in fibrogenesis. Thus the CD8 lymphocytes have been demonstrated to activate HSC in murine models [35] whereas NK cells, components of the innate immune system, have been reported to inhibit liver fibrosis by killing activated HSCs [36]. The interactions between the immune system and stellate cells are not unidirectional. Indeed HSC also modulate the hepatic immune response, notably by release of cytokine/chemokines and function as professional antigen presenting cells [37].

A major interesting point of our study is the simultaneous expression of three sheddases and a common substrate by HSC suggesting complex regulation of CX3CL1 cleavage. The sheddase might be involved in a sequential cleavage of CX3CL1 or activated in response to different stimuli. Indeed ADAM10 was widely involved in constitutive shedding of CX3CL1 however a calcium-dependent pathway has been recently implicated in leucocytes detachment process [38]. Shedding activity of ADAM17 requires cell stimulation by the PKC activator, PMA; however, how physiological activation occurs in tissues remains unclear. MMP-2 requires a processing step of activation at the cell surface [39] and we and other groups have previously reported that extracellular stimuli, including ConA or type I collagen [28, 31, 40] are required to induce MMP-2 activation. These data suggest that the fibrogenic microenvironment favours MMP-2 activation thereby facilitating sustained inflammatory cells recruitment. Further studies are required to understand how metalloproteinase activities are locally coordinated to promote CX3CL1 shedding during chronic liver disease. In conclusion, this study has shown that the expression of ADAM10/ADAM17 and CX3CR1/CX3CL1 are increased in chronic liver diseases. Up-regulation of ADAM10 and ADAM17 was associated with the grade of fibrosis and HSC; however, these ADAMs only partially contribute to the shedding of CX3CL1. Activation of MMP-2 induces the release of chemotactic peptides from CX3CL1 in HSC stimulated by inflammatory and fibrogenic microenvironment. Taken together, our data suggest that metalloproteinases synthesized by HSC contribute not only to matrix degradation but also to sustained inflammation by providing shedding activities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer the Ligue Contre le Cancer and the Region Bretagne (PRIR n° 3193). K.B.-B. was a recipient of a post-fellowship from the Region Bretagne. We thank Dr. A. Ludwig, Dr. C. CombadiËre and British Biotech for providing the ADAM inhibitor GW280264X, HEK-CX3CR1 cells and Batimastat, respectively. We thank S. Dutertre (IFR 140, Rennes) for microscopy analyses and the Biological Ressource Center (CHRU Pontchaillou, IFR 140) for contribution to human tissue sampling. We thank A. Vannier for secretarial work and Drs. G. Baffet and S. LangouÎt for critical comments on the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

S1. Effect of IFN-γ on ADAM10, ADAM17 and MMP-2expression in human hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Human culturedHSC were either unstimulated or stimulated with IFN-γ (1(μg/ml) for 15 hrs and mRNA levels were measured byreal-time PCR. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. from a representative experiment. Results are represented as fold increase of control.

S2. Involvement of MMP-2 in CX3CL1 cleavage.IFN-γ-stimulated human HSC were treated with or without PMAin presence or absence of chemical inhibitors either directedagainst MMP, batimastat, or ADAM10 and ADAM17, GW280264X. SolubleCX3CL1 was measured in conditioned media. Data are expressed asmean ± S.D. from a representative experiment.

This material is available as part of the online article from: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00787.x (This link will take you to the article abstract).

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1655–69. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marra F. Chemokines in liver inflammation and fibrosis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1899–914. doi: 10.2741/A887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson KJ, Henderson NC, Bone-Larson CL, et al. Chemokines in the pathogenesis of liver disease: so many players with poorly defined roles. Clin Sci. 2003;104:47–63. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laing KJ, Secombes CJ. Chemokines. Dev Comp Immunol. 2004;28:443–60. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bazan JF, Bacon KB, Hardiman G, et al. A new class of membrane-bound chemokine with a CX3C motif. Nature. 1997;385:640–4. doi: 10.1038/385640a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garton KJ, Gough PJ, Blobel CP, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (ADAM17) mediates the cleavage and shedding of fractalkine (CX3CL1) J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37993–8001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsou CL, Haskell CA, Charo IF. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme mediates the inducible cleavage of fractalkine. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44622–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107327200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imai T, Hieshima K, Haskell C, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, which mediates both leukocyte migration and adhesion. Cell. 1997;91:521–30. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80438-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lucas AD, Bursill C, Guzik TJ, et al. Smooth muscle cells in human atherosclerotic plaques express the fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 and undergo chemotaxis to the CX3C chemokine fractalkine (CX3CL1) Circulation. 2003;108:2498–504. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097119.57756.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efsen E, Grappone C, DeFranco RM, et al. Up-regulated expression of fractalkine and its receptor CX3CR1 during liver injury in humans. J Hepatol. 2002;37:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isse K, Harada K, Zen Y, et al. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 are involved in the recruitment of intraepithelial lymphocytes of intrahepatic bile ducts. Hepatology. 2005;41:506–16. doi: 10.1002/hep.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang L, Hu HD, Hu P, et al. Gene therapy with CX3CL1/Fractalkine induces antitumor immunity to regress effectively mouse hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene Ther. 2007;14:1226–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsubara T, Ono T, Yamanoi A, et al. Fractalkine-CX3CR1 axis regulates tumor cell cycle and deteriorates prognosis after radical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95:241–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huovila AP, Turner AJ, Pelto-Huikko M, et al. Shedding light on ADAM metalloproteinases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:413–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hundhausen C, Misztela D, Berkhout TA, et al. The disintegrin-like metalloproteinase ADAM10 is involved in constitutive cleavage of CX3CL1 (fractalkine) and regulates CX3CL1-mediated cell-cell adhesion. Blood. 2003;102:1186–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Theret N, Musso O, Turlin B, et al. Increased extracellular matrix remodeling is associated with tumor progression in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Hepatology. 2001;34:82–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman SL. Hepatic stellate cells: protean, multifunctional, and enigmatic cells of the liver. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:125–72. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding X, Yang LY, Huang GW, et al. ADAM17 mRNA expression and pathological features of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2735–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i18.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita T, Maesawa C, Oikawa K, et al. Interferon-gamma down-regulates expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme/a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 in activated hepatic stellate cells of rats. Int J Mol Med. 2006;17:605–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Pabic H, Bonnier D, Wewer UM, et al. ADAM12 in human liver cancers: TGF-beta-regulated expression in stellate cells is associated with matrix remodeling. Hepatology. 2003;37:1056–66. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwettmann L, Wehmeier M, Jokovic D, et al. Hepatic expression of A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase (ADAM) and ADAMs with thrombospondin motives (ADAM-TS) enzymes in patients with chronic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2008;49:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arthur MJ, Stanley A, Iredale JP, et al. Secretion of 72 kDa type IV collagenase/gelatinase by cultured human lipocytes. Analysis of gene expression, protein synthesis and proteinase activity. Biochem J. 1992;287:701–7. doi: 10.1042/bj2870701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milani S, Herbst H, Schuppan D, et al. Differential expression of matrix-metallo-proteinase-1 and -2 genes in normal and fibrotic human liver. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:528–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theret N, Musso O, L’Helgoualc’h A, Clement B. Activation of matrix metallo-proteinase-2 from hepatic stellate cells requires interactions with hepatocytes. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:51–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foda HD, George S, Conner C, et al. Activation of human umbilical vein endothelial cell progelatinase A by phorbol myristate acetate: a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism involving a membrane-type matrix metalloproteinase. Lab Invest. 1996;74:538–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker AH, Edwards DR, Murphy G. Metalloproteinase inhibitors: biological actions and therapeutic opportunities. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3719–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cambien B, Pomeranz M, Schmid-Antomarchi H, et al. Signal transduction pathways involved in soluble fractalkine-induced monocytic cell adhesion. Blood. 2001;97:2031–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theret N, Lehti K, Musso O, Clement B. MMP2 activation by collagen I and concanavalin A in cultured human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 1999;30:462–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hemmann S, Graf J, Roderfeld M, Roeb E. Expression of MMPs and TIMPs in liver fibrosis – a systematic review with special emphasis on anti-fibrotic strategies. J Hepatol. 2007;46:955–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knittel T, Mehde M, Kobold D, et al. Expression patterns of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in parenchy-mal and non-parenchymal cells of rat liver: regulation by TNF-alpha and TGF-beta1. J Hepatol. 1999;30:48–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahara T, Furui K, Yata Y, et al. Dual expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and membrane-type 1-matrix metalloproteinase in fibrotic human livers. Hepatology. 1997;26:1521–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wasmuth HE, Zaldivar MM, Berres ML, et al. The fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 is involved in liver fibrosis due to chronic hepatitis C infection. J Hepatol. 2008;48:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overall CM, Dean RA. Degradomics: systems biology of the protease web. Pleiotropic roles of MMPs in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:69–75. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7890-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dean RA, Overall CM. Proteomics discovery of metalloproteinase substrates in the cellular context by iTRAQ labeling reveals a diverse MMP-2 substrate degradome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:611–23. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600341-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Safadi R, Ohta M, Alvarez CE, et al. Immune stimulation of hepatic fibrogenesis by CD8 cells and attenuation by transgenic interleukin-10 from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:870–82. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Notas G, Kisseleva T, Brenner D. NK and NKT cells in liver injury and fibrosis. Clin Immunol. 2009;130:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unanue ER. Ito cells, stellate cells, and myofibroblasts: new actors in antigen presentation. Immunity. 2007;26:9–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hundhausen C, Schulte A, Schulz B, et al. Regulated shedding of transmembrane chemokines by the disintegrin and metalloproteinase 10 facilitates detachment of adherent leukocytes. J Immunol. 2007;178:8064–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.8064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strongin AY, Collier I, Bannikov G, et al. Mechanism of cell surface activation of 72-kDa type IV collagenase. Isolation of the activated form of the membrane metalloprotease. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5331–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preaux AM, Mallat A, Nhieu JT, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 activation in human hepatic fibrosis regulation by cell-matrix interactions. Hepatology. 1999;30:944–50. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.