Abstract

Objectives. Our aim was to determine if the decrease in drug use disorders with age is attributable to changes in persistence, as implied by the notion of maturing out. Also, we examined the association between role transitions and persistence, recurrence, and new onset of drug use disorders.

Methods. We performed secondary analysis of the 2 waves of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions data (baseline assessment 2001–2002, follow-up conducted 2004–2005). We conducted logistic regressions and multinomial logistic regression to determine the effect of age on wave 2 diagnosis status, as well as the interaction between age and role transitions.

Results. Rates of persistence were stable over the life span, whereas rates of new onset and recurrence decreased with age. Changes in parenthood, marital, and employment status were associated with persistence, new onset, and recurrence. We found an interaction between marital status and age.

Conclusions. Our findings challenge commonly held notions that the age-related decrease in drug use disorders is attributable to an increase in persistence, and that the effects of role transitions are stronger during young, compared with middle and older, adulthood.

Since Winick’s seminal report of cessation in drug addiction during the third decade of life,1 the notion that most drug users mature out has been extensively discussed and replicated across different samples and substances.2–6 Indeed, it is widely recognized that the rates of both drug consumption and drug use disorders (i.e., abuse and dependence) decrease dramatically over the life span7–11 (with an exception to this regarding alcohol use12). For example, Chen and Kandel7 reported longitudinal data on high-school students followed up until their 30s. They found that initiation of drug use tends to occur during late teens and early 20s, whereas cessation tends to occur before the late 20s.

Two nationally representative studies, the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS)11 and the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey (NLAES)9 yielded similar results regarding past-12-month prevalence of use by age, with the youngest participants reporting the highest prevalence. With regard to drug use disorders, both NCS and NLAES also reported a significant decrease with age in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised (DSM-III-R)13 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)14 drug dependence, respectively. In addition, results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) have shown a linear decrease of DSM-IV past-12-month drug abuse and drug dependence with age (although the same pattern is not evident in lifetime estimates).8 The robust empirical finding of a decrease in drug use and drug use disorders has been interpreted as evidence for a maturational process that leads to cessation in drug consumption.

Although this notion of maturing out has been criticized for its vagueness and because it conflates description of the phenomenon with its hypothesized explanation,15 it has inspired more formal theoretical developments. Both role incompatibility16 and social control17 have been proposed as descriptions of the process that leads to maturing out. According to these perspectives, involvement in adult roles—such as marriage or parenthood—puts the drug user in a situation in which consumption is not compatible with the demands and expectations of those responsibilities (role incompatibility) or in which other individuals in the social environment can exert an influence on the drug user’s behavior to reduce or eliminate consumption (social control).

Consistent evidence has emerged supporting the notion that involvement in adult roles is associated with changes in drug use and, although less consistently, drug use disorders. The Monitoring the Future Study has shown that unemployment is associated with higher rates of drug use, and that being married and being a custodial parent are associated with lower rates of drug use among adults,18 although these effects may vary with age.19–21 In addition, prospective Monitoring the Future Study data have shown that family role transitions, including marriage and parenthood, are strongly associated with reductions in drug use beyond selection effects.22 Likewise, Kandel and Raveis23 reported that first-time marriage predicted cessation of marijuana use among men and women, and becoming a parent predicted cessation of both marijuana and cocaine use among women. However, the evidence regarding drug use disorders is not as pervasive or consistent. Overbeek et al.24 found that changes in marital status and parenthood prospectively predicted the onset of DSM-III-R drug use disorders. However, findings from the first wave of NESARC showed that remission from cannabis and cocaine dependence is not associated with marital status.25 Although this report used cross-sectional data, results cast doubt on the generalization of findings from drug use to drug use disorders.

Regardless of the evidence related to role transitions, the general notion of maturing out can be questioned by examining data on drug use disorder persistence. In particular, the concept of maturing out assumes that most individuals with a drug use disorder achieve remission relatively early in life, so that rates of remission are higher among younger than older individuals. When the same issue is examined in terms of persistence, the expectation is that older people will have higher rates of persistence than their younger counterparts (i.e., decreases in overall drug use disorder prevalence with age will be reflected in increases in drug use disorder persistence with age). However, the limited evidence on persistence available shows the opposite pattern; in both NCS11 and NLAES,9 the rates of drug dependence persistence (assessed retrospectively) decreased with age. Although the definition of persistence used in NCS has been criticized9 for using an inappropriate subsample (i.e., past-12-month dependence among individuals with lifetime dependence), NLAES used a more appropriate definition of persistence (i.e., past-12-month dependence among individuals with prior-to-past-year dependence). However, even the latter definition can be questioned because it is based on cross-sectional data and conflates persistence and recurrence.26

The first goal of the current study was to investigate to what extent the decline in drug use disorders with age is attributable to changes in persistence, as implied by the notion of maturing out. An advantage of the current study over previous studies addressing the issue of persistence is that we used longitudinal data from both waves of NESARC to define persistence as the rate of past-year drug use disorders among individuals diagnosed 3 years earlier. In addition, the availability of longitudinal data permits distinction between persistence and recurrence (by using information about prior-to-past-year vs past-year diagnosis at wave 1). Thus, the relative contribution of persistence to the rates of drug use disorders can be compared with the contribution of 2 other components, recurrence and new onset, to determine which component better accounts for the decrease in drug use disorders across the life span.

The second goal was to determine the association of role transitions and rates of persistence, recurrence, and new onset. As mentioned previously, although there is consistent evidence regarding the effect of role transition on changes in drug use, this has yet to be shown for drug use disorders. Moreover, we also examined the extent to which this association is moderated by age, given that the concept of maturing out implies a stronger effect of role transitions among younger individuals. If this is true, a significant interaction of age and role transitions should be found, whereas nonsignificant interactions or interactions showing the opposite pattern (i.e., stronger effects among older individuals) should be taken as evidence against the concept of maturing out.

METHODS

The NESARC is a nationally representative survey of civilians aged 18 years and older.27,28 The survey oversampled Blacks, Hispanics, and young adults aged 18 to 24 years. To examine new onsets, persistence, and recurrence of drug use disorders, we took advantage of NESARC’s longitudinal design. Baseline assessment (n = 43 093) was conducted in 2001–2002, whereas follow-up (n = 34 653) was conducted in 2004–2005.

Measures

Drug use disorders.

The NESARC team assessed drug use disorders with the Alcohol Use Disorders and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV version (AUDADIS-IV).29 The AUDADIS-IV is a structured diagnostic interview that measures DSM-IV diagnoses in both past-12-month, and prior-to-past-12-month time frames. The substances assessed in the AUDADIS-IV drug use disorders included sedatives, tranquilizers, opiates, stimulants, hallucinogens, cannabis, cocaine, inhalants or solvents, heroin, and other drugs (e.g., steroids, antipsychotics, etc.). Drug use disorders provided by the AUDADIS-IV have been shown to be reliable in a number of studies.30,31

Role transitions.

We examined 3 categories of role transitions: change in parenthood, change in marital status, and change in employment status. We measured marital status changes from a variable included at wave 2, which indexed changes taking place during the follow-up period. To assess change in parenthood and employment status, we created variables based on data from both waves. We used broad definitions of parenthood and marriage, with parenthood including having any adopted, foster, or step children, and being married including starting living with someone as if married. In addition, we created broad categories because of sparseness of the data in subgroup analyses. We categorized parenthood as “stable nonparent,” “stable parent,” and “new child.” The latter category includes individuals who were parents at baseline and had a new child as well as individuals who became parents for the first time. For the same reason, we did not distinguish among participants who were “stable” because they remained married or unmarried, or those who remained employed or unemployed. Likewise, we collapsed the unemployed and retired categories into a single category.

Other variables.

We categorized age into 6 groups for the analysis of prevalence, and into 2 groups for the interactions with role transitions because of sparseness of the data. We included gender and ethnicity only as covariates.

Analysis

NESARC utilized a complex sampling design. We used SUDAAN version 9.0 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to adjust for sampling weights in the calculation of standard errors of parameter estimates. Weights used at wave 2 also adjusted for attrition and wave 1 lifetime psychiatric disorders.

We classified participants with a past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 2 (n = 748) into 3 mutually exclusive groups according to their baseline diagnostic status. The “new onset” group consisted of participants with no lifetime (i.e., no prior-to-past-12-month or past-12-month) drug use disorder at wave 1 (n = 349); the “persistence” group consisted of participants with a past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 1 (n = 208); and, finally, the “recurrence” group consisted of participants who had a prior-to-past-12-month drug use disorder but no past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 1 (n = 191). Changes in the 3 groups over the life span are presented in 2 complementary ways: in simultaneous presentation, to show their relative contribution to the overall prevalence of drug use disorder, and separately, to show changes in each group for those “at risk” for that outcome, as defined at wave 1 (e.g., persistence among those diagnosed with a drug use disorder at wave 1). In addition to these 3 groups, we created a referent group for comparison, comprising participants who were not diagnosed with past-year drug use disorder at wave 2 (n = 33 905).

We conducted multinomial logistic regression analysis, including all 4 groups as levels of the dependent variable, to determine the effect of age on drug use disorder status, adjusting for gender and race. To determine whether the effect of role transitions on drug use disorder status varies across the life span, the model included interactions of role transitions with age (categorized in 2 groups—18–34 years and ≥ 35 years—to highlight the period in which most role transitions are normative). We could not examine moderation by gender because of low sample sizes in some groups.

RESULTS

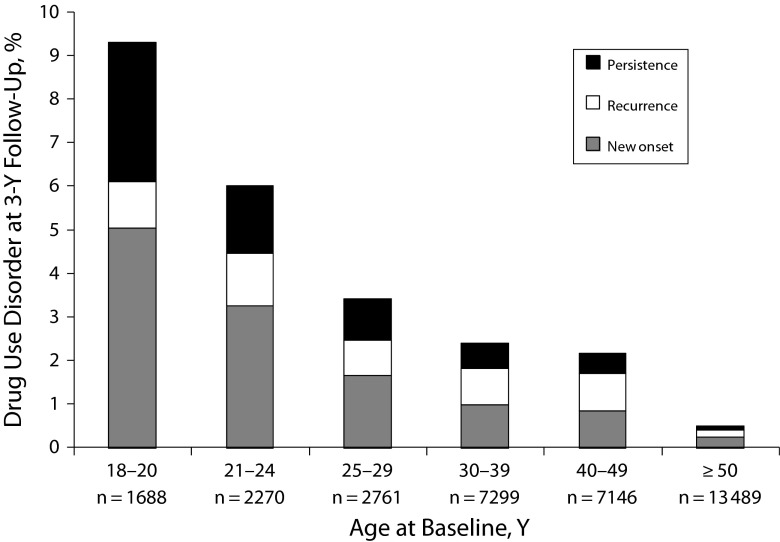

A decrease in past-12-month drug use disorder across the life span is shown in Figure 1, consistent with the overall literature.7–11 Drug use disorder prevalence at wave 2 decreased dramatically from 9.3% at age 18 to 20 years to 0.5% at age 50 years or older. Furthermore, Figure 1 decomposes the overall prevalence into the relative contribution of the 3 groups. The relative contribution of new onset at each age remained relatively stable (54% at age 18–20 years, 49% at age 50 years or older). By contrast, the relative contribution of persistence decreased (from 35% to 18%) and the relative contribution of recurrence increased (from 12% to 33%).

FIGURE 1—

Relative contribution of the 3 drug use disorder groups to the overall drug use disorder prevalence across age groups: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2002 and 2004–2005.

Note. The y-axis represents the percentage of participants diagnosed with past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 2.

Figures A, B, and C (available as supplements to this article at http://www.ajph.org) show changes with age separately for each group. Three separate logistic regressions showed persistence (Wald F5,65 = 0.29; P = .92) was stable across age groups, whereas onset (F5,65 = 63.44; P < .001) and recurrence (F5,65 = 3.30; P < .05) decreased significantly with age.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the 4 groups. We examined differences between groups for each variable through pairwise comparisons, requiring a P value of less than .01 to account for multiple tests. The most substantial differences were between individuals with no drug use disorder diagnosis at wave 2 and the other groups. Participants with no drug use disorder diagnosis at wave 2 were significantly older, were less likely to be men, were more likely to be married at both waves, and were more likely to be parents at wave 1. Although the 3 drug use disorder groups were similar across variables, the recurrence group tended to be closer than the other 2 groups to the group with no drug use disorder diagnosis at wave 2. We found no differences among groups for race and employment status.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of the Drug Use Disorder Groups: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2002 and 2004–2005

| Drug Use Disorder at Wave 2, % (SE) |

|||||

| Variable | Wald F3,65 | No Drug Use Disorder at Wave 2 (n = 33 905), % (SE) | Persistence (n = 208)a | Onset (n = 349)b | Recurrence (n = 191)c |

| Age 18–34 yd | 80.83* | 30.8 (0.4)c | 70.6 (3.9)a | 68.1 (3.0)a | 45.2 (4.5)b |

| Maled | 25.82* | 47.5 (0.4)a | 70.0 (3.8)b | 62.2 (3.5)b | 70.6 (4.0)b |

| Whited | 1.08 | 70.9 (1.6)a | 73.3 (3.9)a | 69.1 (3.2)a | 77.2 (3.8)a |

| Married | |||||

| Wave 1 | 43.15* | 63.7 (0.5)c | 30.2 (4.7)a | 34.5 (3.1)a | 52.2 (3.9)b |

| Wave 2 | 51.03* | 64.5 (0.5)c | 29.6 (4.3)a | 33.4 (3.1)a | 48.3 (4.2)b |

| Parent | |||||

| Wave 1 | 65.34* | 73.5 (0.5)c | 34.9 (4.1)a | 43.7 (3.6)a | 63.4 (4.0)b |

| Wave 2 | 66.30* | 77.1 (0.5)b | 39.5 (4.1)a | 48.4 (3.6)a | 69.0 (3.9)b |

| Employed | |||||

| Wave 1 | 0.43 | 66.0 (0.4)a | 66.9 (4.1)a | 67.7 (2.7)a | 69.3 (3.7)a |

| Wave 2 | 2.61 | 64.9 (0.4)a | 73.1 (3.8)a | 68.6 (2.9)a | 70.3 (3.7)a |

Note. Wald F tested the overall effect for each variable. We assessed differences between groups for each variable by using pairwise comparisons. Values that share the same subscript letter by row are not statistically different at P < .01.

Past-12-month drug use disorder at waves 1 and 2.

No lifetime drug use disorder at wave 1 and past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 2.

Lifetime but not current drug use disorder at wave 1 and past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 2.

Assessed at wave 1.

*P < .01.

Results from the multinomial logistic regression examining persistence, onset, and recurrence (with no drug use disorder diagnosis at wave 2 as referent group) are shown in Table 2. Only the overall interaction of age and change in marriage status was significant (F6,65 = 3.13; P < .01). Follow-up contrasts revealed significant interactions for both persistence (F2,65 = 3.49; P < .05) and recurrence (F2,65 = 5.48; P < .01). Simple effects analyses of interactions (shown in Figures D and E, available as supplements to this article at http://www.ajph.org) indicate that marriage dissolution was associated with persistence of drug use disorder only among older individuals (F2,65 = 5.42; P < .01) and with recurrence of drug use disorder only among younger individuals (F2,65 = 10.30; P < .01). In addition, main effects suggested that marriage dissolution was associated with new onset of drug use disorder regardless of age (odds ratio [OR] = 2.78; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.34, 5.75). Also, being a parent at both waves or having a new child at wave 2 was associated with lower rates of persistence (OR = 0.26; 95% CI = 0.14, 0.49; and OR = 0.27; 95% CI = 0.15, 0.50, respectively) and new onset (OR = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.26, 0.68; and OR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.29, 0.82, respectively) of drug use disorder. In a similar way, both losing a job (OR = 2.90; 95% CI = 1.20, 6.99) and getting a new job (OR = 3.80; 95% CI = 1.97, 7.32) between waves were associated with persistence of drug use disorder, although only losing a job (OR = 2.00; 95% CI = 1.13, 3.55) was associated with new onset of drug use disorder. The absence of significant interactions involving parenthood and change in employment status indicated that these associations were stable across ages.

TABLE 2—

Analysis of Predictors of Drug Use Disorder Transitions: National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2002 and 2004–2005

| Predictors | Peristence (n = 174),a OR (95% CI) | Onset (n = 264),b OR (95% CI) | Recurrence (n = 158),cOR (95% CI) |

| Gender (Ref: female) | 2.28 (1.45, 3.57) | 1.61 (1.10, 2.34) | 3.00 (1.94, 4.63) |

| Race (Ref: White) | 0.71 (0.44, 1.16) | 1.01 (0.72, 1.42) | 0.78 (0.49, 1.24) |

| Age (Ref: 18–34 y) | 0.21 (0.11, 0.39) | 0.29 (0.15, 0.54) | 0.70 (0.32, 1.55) |

| Parenthood (Ref: stable nonparent) | |||

| Stable parent | 0.26 (0.14, 0.49) | 0.42 (0.26, 0.68) | 0.76 (0.38, 1.52) |

| New child | 0.27 (0.15, 0.50) | 0.49 (0.29, 0.82) | 1.11 (0.55, 2.24) |

| Change marital (Ref: stable) | |||

| Divorced | 0.70 (0.20, 2.42) | 2.78 (1.34, 5.75) | 5.77 (2.65, 12.56) |

| Married | 1.13 (0.66, 1.94) | 1.15 (0.62, 2.15) | 1.73 (0.86, 3.47) |

| Change in job (Ref: stable) | |||

| Lost job | 2.90 (1.20, 6.99) | 2.00 (1.13, 3.55) | 1.85 (0.61, 5.61) |

| New job | 3.80 (1.97, 7.32) | 1.71 (0.75, 3.93) | 1.39 (0.51, 3.76) |

| Age × parenthood (overall interaction term P = .883; Ref: 18–34 y, stable nonparent) | |||

| ≥ 35 y × stable parent | 1.82 (0.66, 5.01) | 1.06 (0.51, 2.21) | 1.19 (0.47, 3.01) |

| ≥ 35 y × new child | 1.08 (0.12, 9.35) | 1.72 (0.44, 6.75) | 0.90 (0.25, 3.32) |

| Age × change marital (overall interaction term P = .009; Ref: 18–34 y, stable) | |||

| ≥ 35 y × divorced | 5.78 (1.14, 29.19) | 1.21 (0.40, 3.64) | 0.17 (0.05, 0.52) |

| ≥ 35 y × married | 0.21 (0.03, 1.76) | 2.55 (0.60, 10.82) | 1.26 (0.43, 3.66) |

| Age × change in job (overall interaction term P = .443; Ref: 18-34 y, stable) | |||

| ≥ 35 y × lost job | 0.12 (0.01, 1.02) | 0.70 (0.28, 1.78) | 0.60 (0.14, 2.47) |

| ≥ 35 y × new job | 1.19 (0.34, 4.20) | 0.51 (0.11, 2.48) | 1.74 (0.27, 11.12) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Sample sizes differ from those in Table 1 because of missing data in the role transition variables. Reference group for multinomial logistic regression is no drug use disorder diagnosis at wave 2.

Past-12-month drug use disorder at waves 1 and 2.

No lifetime drug use disorder at wave 1 and past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 2.

Lifetime but not current drug use disorder at wave 1 and past-12-month drug use disorder at wave 2.

DISCUSSION

The current results show that, although at the descriptive level the notion of maturing out is quite robust (i.e., there is a steep decline in drug use disorders with age), 2 of the implied explanatory aspects of this concept can be questioned. First, the decrease in drug use disorders with age is not attributable to relatively lower rates of persistence in younger cohorts. Indeed, the observed rates of persistence over a 3-year period were surprisingly stable across age strata. Thus, the decrease in overall drug use disorders seems to be mostly attributable to a corresponding decrease in the rates of new onset (i.e., hazard rates) and, to a lesser extent, in the rates of recurrence. This finding, which is similar to results reported for alcohol dependence,26 suggests that the age effect on drug use disorders reflects reductions in vulnerability to new and previous drug problems rather than actual changes in remission from a baseline diagnosis.

Second, we found no interactions involving age and parenthood or employment status, suggesting that the effect of these role transitions is not necessarily stronger in young adulthood. Rather, the identified associations involving these transitions tended to be stable across the life span. In addition, although the interaction of age and marriage status predicting recurrence suggested a stronger effect of marriage dissolution among younger participants, the interaction predicting persistence suggested a stronger effect of marriage dissolution among older participants. This latter finding is inconsistent with the notion that role transitions have a major effect only at earlier stages of development.

Our results differ from those based on cross-sectional studies. Findings from NCS11 and NLAES,9 although based on different definitions of persistence, both led to the conclusion that persistence decreases with age. By contrast, our findings, from a longitudinal assessment of persistence, suggest a stable prevalence across age groups. We reported elsewhere26 that one could arrive at very different conclusions regarding changes in persistence with age, depending on the way the data are analyzed. Cross-sectional analyses demonstrate a decrease in persistence with age; however, if data from the same study are analyzed longitudinally, more stability (or even an increase) in persistence is revealed. We argue that a longitudinal perspective on persistence is preferable because it is not dependent on lifetime assessments and it provides the same timeframe for all ages (in this case, the 3-year follow-up), so that age is not confounded with persistence. This is supported by recent NESARC findings regarding recovery from alcohol dependence, showing that longitudinal analyses lead to conclusions that differ from cross-sectional analyses of the same data set (with the potential exception of pseudoprospective survival analyses).32

The current results involving role transitions are consistent with the broader literature. Becoming a parent has been reported as a strong protective factor against persistence of drug use,22 although this effect might be specific to women.23,33 To our knowledge, our study is the first report of the parent effect at the syndromal disorder level and not mere use. However, in this study we could not examine interactions with gender because of the sparseness of the data.

The negative impact of marriage dissolution has also been addressed in the literature but with less consistent results. Staff et al.22 reported that being separated, divorced, or widowed was associated with higher levels of drug use. Labouvie4 also reported that participants who become unmarried exhibited smaller decreases in their drug consumption. Overbeek et al.24 found a similar effect on the onset of DSM-III-R drug use disorders, but it was higher among individuals who experienced the dissolution of a relationship other than marriage or cohabitation (dissolution of marriage or cohabitation was also associated but this effect, although large in magnitude, was not significant). In a similar way, a previous analysis from NESARC showed that separation or divorce was associated with cannabis use onset, but only among older individuals.19 By contrast, a report of data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area34 study found that marital status did not predict cocaine initiation. However, the Epidemiologic Catchment Area report did not include marital dissolution in the analysis. Thus, our findings provide additional evidence of a link between marital dissolution and the new onset of drug use disorders, together with evidence that this association might be moderated by age for persistence and recurrence.

Finally, our finding that losing a job was associated with higher rates of new onset and persistence of drug use disorders is in accordance with reports that employment status is associated with initiation of consumption.18,19,22 However, these effects have been reported to be weaker than the effects of marriage and parenthood.22 Moreover, some of the associations found for employment status have been related to obtaining a job rather than losing one,19,26,34 and we found both types of change in employment status to be related with drug use disorder persistence.

In sum, the present report shows significant evidence regarding problems with our current conceptualization of maturing out. Although the decrease in drug use disorders with age has been understood as a product of changes in the rates of persistence, the current findings suggest that persistence is very stable over the life span, so that the age effect on drug use disorders is more reflective of changes in vulnerability to new onset or recurrence. In addition, though role transitions are usually assumed to have a more significant effect during young adulthood, we found little evidence of this. Instead, role transitions seem to be as influential among older individuals in this sample.

Moreover, rather than suggesting that there is a “developmentally limited”35,36 form of substance use disorder that tends to remit in the third decade of life, the steep decline in the age–prevalence curve during this life stage reflects changes in new onset rates and not remission rates. Although there are likely developmental contributions to such remission, the consistency of the remission rates over the life course suggests that developmental factors are relevant throughout adulthood. This also indicates that we need to look further at role transitions that are conditioned to life stage. Indeed, changes in marital status, parenthood, and employment mean different things at different ages (e.g., parenthood at age 18 years vs parenthood at age 40 years). As a consequence, future research on maturing out needs to extend beyond the parochial lens of emerging adulthood and consider psychosocial maturation and lifelong process that is associated with different contexts and developmental tasks that could contribute to both substance use and drug use disorder.

The NESARC study has a number of considerable strengths including excellent recruitment and retention rates; a large, nationally representative sample; and a well-validated, structured interview. However, some limitations of this study should be noted. Perhaps most critically, because of the sparseness of the data, we had to use broad categories to examine role transitions. This limited our ability to distinguish more specific associations. For example, in NLAES, never-married individuals were found to be at higher risk for persistence determined with cross-sectional data.9 We were not able to make this distinction, so those who have never been married are included in the broader category of “stable” in this study. Also, our “new child” category includes participants who became parents for the first time as well as individuals who were already parents and had a new child. Although becoming a parent for the first time is what constitutes the main transition associated with parenthood, it was not possible to examine this group separately. In addition, we were unable to test interactions with gender, although gender differences have been reported in the literature.23,33

Likewise, the absence of age differences regarding parenthood and employment status might be attributable to insufficient power to detect those interactions—in spite of the relatively large sample size in each group—or to the categorization of age in groups that might miss the critical changes taking place during young adulthood. However, despite this limitation, we were still able to observe a significant interaction for marriage status. Also, the assessment of role transitions was contemporaneous with the assessment of persistence, new onset, and recurrence, so that reported associations do not imply a causal direction. We also note that we focused on past-12-month diagnoses at both waves to define persistence, so it is possible that some participants classified as “persistent” experienced a period of remission between waves.

Despite these limitations, we believe the findings regarding the relative contribution of new onsets, persistence, and recurrence to the age–prevalence curve force us to reconsider the declining age–prevalence curve of drug use disorder as reflecting maturing out. Also of considerable importance, these findings highlight the association of role transitions with drug use disorders across the entire life span and not just during early adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (grants K05AA017242 and R01AA016392 to K. J. Sher and P60AA011998 to A. C. Heath).

Human Participant Protection

This study involved secondary analyses of a nationally representative study conducted by the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not needed.

References

- 1.Winick C. Maturing out of narcotic addiction. Bull Narc. 1962;14:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Maturing out of alcohol dependence: the impact of transitional life events. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(2):195–203. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jochman KA, Fromme K. Maturing out of substance use: the other side of etiology. In: Scheier LM, editor. Handbook of Drug Use Etiology: Theory, Methods, and Empirical Findings. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labouvie E. Maturing out of substance use: selection and self-correction. J Drug Issues. 1996;26(2):457–476. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(2):360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heyman GM. Quitting drugs: quantitative and qualitative features. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143041. Epub ahead of print January 16, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen K, Kandel DB. The natural history of drug use from adolescence to the mid-thirties in a general population sample. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(1):41–47. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(5):566–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant BF. Prevalence and correlates of drug use and DSM-IV drug dependence in the United States: results of the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1996;8(2):195–210. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(96)90249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stinson FS, Ruan WJ, Pickering R, Grant BF. Cannabis use disorders in the USA: prevalence, correlates and co-morbidity. Psychol Med. 2006;36(10):1447–1460. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner LA, Kessler RC, Hughes M, Anthony JC, Nelson CB. Prevalence and correlates of drug use and dependence in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(3):219–229. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950150051010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm ND, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS Project. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maddux JF, Desmond DP. New light on the maturing out hypothesis in opioid dependence. Bull Narc. 1980;32(1):15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi K, Kandel D. On the resolution of role incompatibility: life event history analysis of family roles and marijuana use. Am J Sociol. 1985;90:1284–1325. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umberson D. Family status and health behaviors: social control as a dimension of social integration. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28(3):306–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merline AC, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Substance use among adults 35 years of age: prevalence, adulthood predictors, and impact of adolescent substance use. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(1):96–102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. Correlates of later-onset cannabis use in the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1-2):71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burton RP, Johnson RJ, Ritter C et al. The effects of role socialization of the initiation of cocaine use: an event history analysis from adolescence into middle adulthood. J Health Soc Behav. 1996;37(1):75–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chassin L, Hussong A, Beltran I. Adolescent substance use. In: Lerner R, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J et al. Substance use changes and social role transitions: proximal developmental effects on ongoing trajectories from late adolescence through early adulthood. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(4):917–932. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kandel DB, Raveis VH. Cessation of illicit drug use in young adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(2):109–116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810020011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Overbeek G, Vollebergh W, Engels RC, Meeus W. Young adults’ relationship transitions and the incidence of mental disorders: a three-wave longitudinal study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2003;38(12):669–676. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Quintero C, Hasin DS, de Los Cobos JP et al. Probability and predictors of remission from life-time nicotine, alcohol, cannabis or cocaine dependence: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction. 2011;106(3):657–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vergés A, Jackson KM, Bucholz KK et al. Deconstructing the age-prevalence curve of alcohol dependence: why “maturing out” is only a small piece of the puzzle. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121(2):511–523. doi: 10.1037/a0026027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grant BF, Kaplan KD. Source and Accuracy Statement for the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant BF, Moore TC, Kaplan KD. Source and Accuracy Statement: Wave 1 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Hasin DS. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS-IV) Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant BF, Harford TC, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Pickering RP. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a general population sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01134-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasin D, Carpenter KM, McCloud S, Smith M, Grant BF. The Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS): reliability of alcohol and drug modules in a clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44(2-3):133–141. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Ruan WJ, Grant BF. Correlates of recovery from alcohol dependence: a prospective study over a 3-year follow-up interval. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(7):1268–1277. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen K, Kandel DB. Predictors of cessation of marijuana use: an event history analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;50(2):109–121. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritter C, Anthony JC. Factors influencing initiation of cocaine use among adults: findings from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. In: Schober S, Schade C, editors. The Epidemiology of Cocaine Use and Abuse. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1991. pp. 189–210. Research monograph 110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zucker RA. The four alcoholisms: a developmental account of the etiologic process. In: Rivers PC, editor. Alcohol and Addictive Behavior. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1987. pp. 27–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zucker RA. Pathways to alcohol problems and alcoholism: a developmental account of the evidence for multiple alcoholisms and for contextual contributions to risk. In: Zucker RA, Howard I, Boyd GM, editors. The Development of Alcohol Problems: Exploring the Biopsychosocial Matrix of Risk. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1994. pp. 255–289. NIAAA Research Monograph 26. [Google Scholar]