Abstract

A great variety of signalling pathways regulating inflammation, cell development and cell survival require NF-κB transcription factors, which are normally inactive due to binding to inhibitors, such as IκBα. The canonical activation pathway of NF-κB is initiated by phosphorylation of the inhibitor by an IκB kinase (IKK) complex triggering ubiquitination of IκB molecules by SCF-type E3-ligase complexes and rapid degradation by 26S-proteasomes. The ubiquitination machinery is regulated by the COP9 signalosome (CSN). We show that IκB kinases interact with the CSN-complex, as well as the SCF-ubiquitination machinery, providing an explanation for the rapid signalling-induced ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα. Furthermore, we reveal that IKK’s phosphorylate not only IκBα, but also the CSN-subunit Csn5/JAB1 (c-Jun activation domain binding protein-1) and that IKK2 influences ubiquitination of Csn5/JAB1. Our observations imply that the CSN complex acts as an inhibitor of constitutive NF-κB activity in non-activated cells. Knock-down of Csn5/JAB1 clearly enhanced basal NF-κB activity and improved cell survival under stress. The inhibitory effect of Csn5/JAB1 requires a functional MPN+ metalloprotease domain, which is responsible for cleaving ubiquitin-like Nedd8-modifications. Upon activation of cells with tumour necrosis factor-α, the CSN complex dissociates from IKK’s allowing full and rapid activation of the NF-κB pathway by the concerted action of interacting protein complexes.

Keywords: inflammation, NF-κB, IκB kinase, protein interactions, ubiquitination, CSN complex, JAB1

Introduction

NF-κB, a key transcription factor for many cellular processes, is activated by a wide variety of signalling pathways, which converge at the level of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, a 700–900 kD protein complex responsible for the phosphorylation of inhibitory IκB molecules on two nearby serine-residues [1]. This phosphorylation induces rapid and efficient poly-ubiquitination of IκB by SCF-type E3 ligases and subsequent degradation by 26S proteasomes often within a few minutes [2–7]. It was our aim to identify molecular mechanisms explaining this rapid ubiquitination and degradation based on a search for interaction partners of the IKK-complex. The SCF-complex responsible for poly-ubiquitination of IκB after phosphorylation by IKK’s comprises Skp1, Cullin-1 and a β-transducin repeat containing protein (βTrCP) as substrate-specific F-box protein [8, 9]. The ubiquitination activity of the SCFβTrCP complex was shown to be up-regulated by covalent attachment of Nedd8, a ubiquitin-like molecule, to the Cullin-moiety of SCF [10]. This so called neddylation apparently represents a general mechanism of SCF regulation [11] and is controlled by a protein complex designated as COP9-signalosome (constitutive photomorphogenesis signalosome, CSN), which is highly conserved from plants to human beings. The CSN complex consists of eight proteins with homologies to subunits of the 19S proteasome regulator and was reported to regulate the degradation of various signalling molecules [12–16]. CSN mediates the cleavage of Nedd8-residues from SCF complexes [17, 18] and leads to an inhibition of ubiquitination reactions in vitro as well as a destabilization of SCF, which is in line with the reported requirement of Nedd8-conjugation for the activity of SCF complexes. However, genetic studies revealed that CSN is actually required for sustained SCF activity in vivo (for review see [12]). This apparent inconsistency, which was termed the CSN paradox is currently explained by a working model postulating that subsequent cycles of neddylation and deneddylation, resulting in assembly and disassembly of SCF complexes, are important for the overall functionality of the ubiquitination machinery and the ‘reloading’ of SCF complexes with fresh, non-ubiquitinated components. Auto-ubiquitination represents a mechanism of SCF-self-inactivation and this process has to be counteracted by de-ubiquitination processes involving accessory proteins, as well as by deneddylation reactions controlling the disassembly and reloading of SCF [12, 19, 20]. The deneddylation activity of the CSN complex could be attributed to the subunit Csn5 [12, 18], also named JAB1 (for c-Jun activation domain binding protein-1 [21]). It could be shown that the Nedd8-cleaving activity depends on a metalloprotease domain within JAB1/Csn5, which is also capable of driving de-ubiquitination reactions [22], therefore allowing two distinct pathways of interference with the SCF complex. Interestingly, JAB1 can also occur in a small complex different from CSN (JAB1 containing small complex, JACS [23, 24]), which is involved in cell cycle regulation and anchorage-dependent signal transduction. Whether and how this complex is functionally related to the CSN complex is currently not clarified.

It was reported that CSN can associate not only with SCF complexes but also with proteasomes [25, 26] indicating that the functional correlation between ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation is also supported by direct molecular associations. These protein-super complexes might be regulated by mutual enzymatic activities. Interestingly, purified fractions of the CSN signalosome contain kinase activity, phosphorylating IκB molecules, c-Jun and p53 [27, 28]. It was reported that casein kinase II and protein kinase D are associated with the CSN complex [29], as well as inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6-kinase [30]. Our search for interaction partners of IKK2 revealed that components of the CSN signalosome, as well as the SCF complex, interact with IKK2 – and thereby identify IKK2 as another CSN-associated kinase. Based on this observation, we show that mutual regulatory mechanisms exist between the NF-κB signalling pathway and the ubiquitination-proteasome system including the CSN complex. A similar, but distinct cross-talk between the NF-κB pathway and the CSN-signalosome was recently reported by Schweitzer et al.[31]. In this report, it was postulated that a CSN-associated deubiquitinylase (USP15) causes a deubiquitination of IκBα representing a negative feedback mechanism of IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation. Our results are in line with a negative regulatory role of the CSN complex in NF-κB activation and identify Csn5/JAB1 and its metalloprotease domain as important constituent of the negative regulatory mechanism. Taken together, these findings imply that the CSN complex interferes at least in two different ways with the ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα. Studies on the role of Csn5/JAB1 in Drosophila support a model, in which CSN5 acts as a negative regulator of the constitutive NF-κB pathway, although it does not block signal induced activation [32].

Materials and methods

Constructs and primers

The yeast 2-hybrid construct for IKK2 was cloned as described [33], as well as flag-tagged IKK2 [34]. Additional 2-hybrid vectors coding for all CSN subunits are described in [35] and the expression vector for His-ubiquitin (pMT107) was a gift of M. Treier [36]. PCR-cloning of myc-tagged expression vectors was done with 5′-EcoR I and 3′-Xho I sites and pcDNA3-myc (a gift from Jan Karlseder, generated by integrating a myc-tag into pcDNA3 from Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). The following primers were used: Csn3: (CCGCGAATTCTGACACAGCTTTGTGAACTGATCAACAAG-forward; CGTGACTCGAGCTCAAGAATAACTGGATGGTTTGTTTCC-reverse); Csn4 (GCTGGAATTCGCAGCGGCTCTCATAAAGATCTGGCTGG-forward; GATAAGCTCGAGGTCACTGAGCCATCTGGGCTTCCATG-reverse); Csn5/JAB1 (TAATGAATTCTGGCGGCGTCCGGGAGCGGTATG-forward; GGCGCTCGAGATTAAGAGATGTTAATTTGATTAAACAGTTTATCCTT-reverse); the MPN-domain of JAB1 (TAATGAATTCTGGCGGCGTCCGGGAGCGGTATG -forward; GATGCTCGAGATTATGGGTATGTCCTAAAGGCGCCA-reverse).

JAB1-mutations in the MPN-domain were generated by a 2-step PCR-strategy. First step: two overlapping JAB1 gene fragments were generated by two PCR reactions using a) JAB1-fw primer (TAATGAATTCTGGCGGCGTCCGGGAGCGGTATG) and JAB1-HH-rev (CATAGCCAGGGGCGCTAGCATACCACCCGATTG) and b) JAB1-rw: GGCGCTCGAGATTAAGAGATGTTAATTTGATTAAACAGTTTATCCTT with JAB1-HH-fw: CAATCGGGTGGTATGCTAGCGCCCCTGGCTATG. Fragments were separated by TAE-gel-electrophoresis and eluted from the gel. Second step: both fragments were mixed and single strands were filled up by Pfu-polymerase by seven cycles of PCR. Then JAB1-fw primer: TAATGAATTCTGGCGGCGTCCGGGAGCGGTATG and JAB1-rw: GGCGCTCGAGATTAAGAGATGTTAATTTGATTAAACAGTTTATCCTT were added and full-length JAB1 containing point mutation was amplified by further 25 PCR cycles. Mutated full-length JAB1 was separated by TAE-gel-electrophoresis and eluted from the gel, digested by EcoR1 and Xho1 and inserted into a pcDNA3-myc vector. By that means the MPN domain HSHPGYGCWLSGID (important amino acids in bold) has been mutated into ASAPGYGCWLSGID (mutated amino acids bold and underlined) resulting in the JAB1-HH/AA mutant. An additional JAB1 mutant was generated in the same way using appropriate mutation primers (fw: GGCTGCTGGCTTGCTGGGATTGCTGTTAGT; rev: GAGTACTAACAGCAATCCCAGCAAGCCAGC) to mutate the other two amino acids (S and D) into alanine (A), resulting in the mutated sequence ASAPGYGCWLAGIA (JAB1-MPN mutant). The gene suppression construct for JAB1 was generated by inserting TCGAGGCAGGAAGCTCAGAGTATCGTTCAAGAGACGATACTCTGAGCTTCCTGCTTTTT-fw and CTAGAAAAAGCAGGAAGCTCAGAGTATCGTCTCTTGAACGATACTCTGAGCTTCCTGCC-rev into IMG-700 (Imgenex, San Diego, CA, USA). The gene suppression construct for IKK2 (si-IKK2) was generated by inserting the sequence AAGCTCTTTACCCTACCCCAA and the reverse complementary sequence, linked by a spacer (TTCAAGAGA) into the pSUPERretro vector (Oligoengine Inc., Seattle, WA, USA). A dominant negative, kinase deficient IKK2 mutant (IKK2mut) was created by site-specific mutagenesis changing lysine K44 into methionine. A constitutive active IKK2 mutant (IKK2ca) was generated by mutating serines S177 and S181 of the activation loop to glutamic acid, which by its negative charge mimics a phosphorylation and thus activation.

Cell culture and transfections

293 cells were cultured as described [37] and transfected with Lipofectamine-Plus™ (Invitrogen) [38] or with calcium/DNA-precipitates [39]. Analysis of transiently transfected cells was generally done 1 day after transfection. Tumour necrosis factor (TNFα) was added to cells at a concentration of 50 ng/ml to activate IKK2 and the NF-κB pathway. MG132 was added to some samples at a concentration of 50 μmol/l to block proteasome activity. Stable myc-JAB1 cells were generated by selection with G418 (500 μg/ml). JAB1-knockdown cells were selected by co-transfection of the suppression construct with a Neomycin-resistance containing plasmid and selection with G418.

Yeast 2-hybrid assays

Yeast 2-hybrid screening was performed as described [33] except that mating of yeast was used to combine the bait with a pre-transformed library from human liver (3 × 106 independent clones, BD Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). 5.9 million transformants were obtained and plated on SD-Leu-Trp-Ade selection plates followed by transfer of positive clones to high stringency selection plates (SD-Leu-Trp-Ade-His + 25 mmol/l 3-aminotriazole). Library inserts were amplified by PCR from yeast colonies and sequenced. Unspecific binding of preys to the Gal4BD of the bait vector was excluded by retransformation of yeast with the library insert and either empty or IKK2-containing pAS2–1 vector. Subsequently all eight CSN subunits as described in [35] were tested for interaction with the IKK2 bait.

Co-immunoprecipitations and immunoblots

Protein interactions were verified for mammalian cells (293 cells) by co-immunoprecipitation studies either after transient transfection with tagged constructs or after precipitation of endogenous proteins with appropriate antibodies. In the first case, flag-tagged IKK2 was transfected either alone or in combination with myc-tagged interaction candidates (Csn3 – Csn5) followed by precipitation with flag-M2-affinity matrix (Sigma) and immunoblotting with anti-myc antibodies (clone 9E10, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-flag (Sigma-Aldrich, Vienna, Austria). Verification of the interaction between the endogenous IKK-complex and the CSN signalosome was achieved by immunoprecipitation of the IKK-complex with anti-IKK2 beads (as described in [33]) followed by Western blot with anti-JAB1-antibodies (Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany, sc-9074) – or by precipitation of the CSN complex with anti-Csn7 obtained from W. Dubiel (precipitating the whole complex – W. Dubiel, personal communication) followed by immunodetection of JAB1 and IKK2 (with anti-IKK2, IMG-129 from Imgenex). The interaction between IKK- and SCF-complexes was shown by immunoprecipitation of IKK-complexes with anti-IKK2 and anti-NEMO antibodies (from Santa Cruz) and immunodetection of endogenous Cul-1 and βTrCP2 (HOS) antibodies (from Labvision-Neomarker and Santa Cruz, respectively). Ubiquitination of JAB1 was assessed by co-transfection of His-tagged ubiquitin and flag-JAB1, immunoprecipitation of JAB1 and detection of ubiquitin-chains with anti-His antibodies (Sigma, H-1029). The turnover of endogenous JAB1 and IKK2 was measured in the presence and absence of TNFα (50 ng/ml) after timed addition of cycloheximide (50 μg/ml) to HUVEC cells, immunoblot analysis of JAB1 or IKK2 levels and quantification of the specific chemiluminescence with LumiImager equipment (Roche, Vienna, Austria). Loading controls for immunoblots were performed with anti-actin-antibodies (Santa Cruz, sc-1616).

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy was done with the 3-Filter method [40] on a Zeiss Axiovert135 microscope equipped with filter sets for ECFP, EYFP and the raw FRET signal (CFP excitation and YFP emission) using a 63× oil immersion objective. Images were taken with a cooled CCD camera (Coolsnap, Roper Scientific GmbH, Ottobrunn, Germany) and processed with the ImageJ plug-in PixFRET as described in [41].

Other assays

Kinase assays were done essentially as in [2] using either wild-type or K44M-mutant IKK2 with recombinant GST-IκBα (described in [33], c-Jun, p53 (Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) or co-expressed/co-precipitated flag-JAB1 as substrates.

Reporter gene assays were done by transfection of a firefly luciferase reporter construct with five NF-κB binding sites (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) and a normalization construct for constitutive expression of β-Galacotosidase (pUB6/V5-His/lacZ, Invitrogen). The reporter enzyme activities were measured with a luciferase reporter substrate (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) on a 96-well luminometer in triplicates.

Apoptosis assays

Apoptotic cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (BD Pharmingen, Schwechat, Austria) and determined by flow analysis.

Ubiquitination assays were performed according to [42] with slight modifications. Briefly, 293 cells were transfected with pMT107 his-ubiquitin expression vector (from Dirk Bohman) in presence of the appropriate expression plasmids. Cells were left untreated or treated with 50 μM MG132 for 4 hrs as indicated in the figure legends. Cells were scraped off the dish and resuspended in 1 ml ice cold PBS. A total of 50 μl of the cell suspension were separated for later whole cell protein control. The remaining cells were lysed in 1 ml Buffer A (6 M guanidine-HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, 10 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Subsequently, the lysed cells were sonicated using small tip sonicator (maximum microtip limit; four pulses of 3 sec. each). After addition of 50 μl equilibrated (50%) Ni-NTA-agarose, samples were incubated at room temperature for 3 hrs. The resin was rinsed twice in Buffer A and twice in Buffer A/TI (1 volume Buffer A, 3 volumes TI Buffer [25 mM Tris.Cl, pH 6.8; 20 mM imidazole, adjust pH to 6.8.]). Finally, the resin was washed with TI Buffer, dissolved in 50 μl 2×SDS-loading dye/ 10 mM imidazole and boiled for 10 min. Ni-NTA purified proteins and whole cell extracts were analysed by Western blotting for the respective tags (myc or flag).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA’s) were performed as described in [33].

Sequence alignments of Csn subunits to determine amino acid similarities and consensus positions were done with VectorNTI (Invitrogen) using the default settings.

Statistics: All data presented in the manuscript are representative of several independent experiments.

Results

IKK complexes interact with CSN- and SCF-complexes

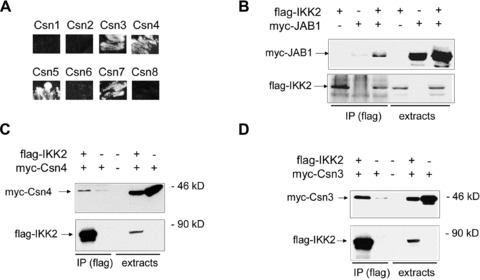

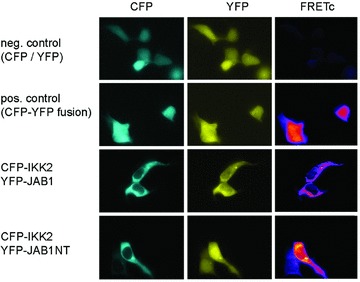

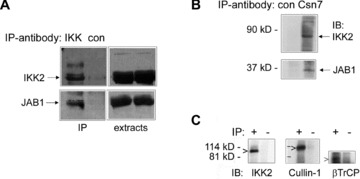

Searching for proteins interacting with IKK2 using a yeast two-hybrid screen (as described in [33]) and a human liver library, we identified the CSN subunits Csn5 and Csn7 as potential interaction partners of IKK2. Further testing of all CSN-subunits (described in [35]), revealed that Csn3, Csn4, Csn5/JAB1 and Csn7 interact with IKK2 in the yeast system indicating that IKK2 might associate not only with a single component of the CSN signalosome but with the complex in its functional entity (Fig. 1A). Sequence alignment of the subunits Csn3, Csn4, Csn5 and Csn7 shows 61% consensus positions, whereas a comparison of all eight subunits reveals a value of just 19% indicating distinct amino acid similarities between the CSN subunits that interact with IKK2. Three of these molecular interactions could be verified in mammalian cells by ectopic expression of flag-tagged IKK2 together with myc-tagged Csn3, Csn4 or Csn5/JAB1, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-flag beads and immunoblotting against the myc-tag (Fig. 1B, C and D). Next, we aimed at identifying the localization of the interaction between IKK2 and Csn5/JAB1 by means of FRET microscopy. CFP-tagged IKK2 was co-expressed with YFP-tagged JAB1 and compared to negative and positive FRET controls. Furthermore, this approach was also applied to test, whether just part of JAB1 is capable of interacting with IKK2. The results clearly showed that IKK2 interacts with JAB1 in the cytosol and that the N-terminal half of JAB1 is sufficient for the interaction (Fig. 2). We also tested whether other components of the IKK complex interact with JAB1 or other proteins of the CSN complex. We found that IKK1 interacts with JAB1/Csn5 and that NEMO/IKKγ– the third molecular component of the IKK complex, associates with Csn3 (Fig. S1). The later observation is in line with a previous report showing an interaction between ectopically expressed IKKγ and Csn3 [43], an interaction which has not been studied functionally in more detail. The multitude of interactions that we identified in the various co-immunoprecipitation experiments obviously indicates a functional link between the IKK-complex and the CSN signalosome. Most importantly, we could confirm the interaction between these two protein-complexes for physiological protein levels in non-transfected cells. Immunoprecipitation of the whole IKK-complex from untreated 293 cells clearly co-precipitated endogenous Csn5/JAB1 (Fig. 3A). However, as this cannot rule out an interaction of IKK-molecules with monomeric JAB1 or with the small JAB1-containing complex JACS [23, 24], we also checked whether IKK2 can be co-precipitated with the CSN-signalosome under conditions that pull down the entire CSN-complex. This could be achieved by CSN-immunoprecipitation with anti-Csn7 antibodies that precipitate the whole complex (W. Dubiel, personal communication) and detection of IKK2, as well as JAB1/Csn5 in the immunoprecipitate (Fig. 3B). As Csn7 is not present in the smaller JAB1 containing complex (termed JACS), these data clearly indicate that IKK molecules interact with CSN. It has been reported that the CSN complex can form a super-complex with SCF-type E3-ligases and proteasomes [26]. This report and our observation that IKK-complexes are associated with CSN – the regulator of SCF-type E3-ligases, prompted us to test, whether the SCFβTrCP-ubiquitination machinery for IκBα has also the capability of interacting with IKK molecules. For answering this question, we performed immunoprecipitation of endogenous IKK-complexes using antibodies against IKK2 and NEMO followed by Western blot analysis of SCF-components. Cullin-1 could be clearly detected in the immunoprecipitate. Furthermore, also βTrCP – the substrate specific F-box protein of the SCF complex binding phosphorylated IκBα was found (Fig. 3C). As expected, we could also detect an interaction between JAB1/Csn5 and the SCF-component Cul-1 in co-immunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. S2). Taken together, our observations indicate the occurrence of multiple protein interactions between IKK-complexes, SCF-type E3-ligases and CSN signalosomes. While just part of the complexes might be associated with each other under the in vitro conditions of co-immunoprecipitations, the observed mutual interactions suggest the possibility of a concerted process of inducible phosphorylation and ubiquitination of IκB molecules, with the latter reaction being regulated by the CSN complex. It is evident that not all of these interactions have to occur simultaneously for a functional cooperativity, or in other words that the various interaction partners do not necessarily form a stable entity – but that the multiple mutual affinities provide a basis for rapid and collaborative enzymatic reactions. Furthermore, the affinities between the signalling molecules and protein complexes generate a signalling network with a high potential of mutual regulatory processes.

Fig 1.

IKK complexes interact with CSN- and SCF-complexes. (A) Interaction of IKK2 with CSN subunits in the yeast two-hybrid system. The original yeast 2-hybrid screen identified Csn5 and Csn7 from a human liver library as interaction partners of the IKK2-bait. Testing all CSN subunits revealed interaction of IKK2 with Csn3, Csn4, Csn5 and Csn7. Shown is the growth of yeast colonies on quadruple-selection medium (minus Leu, Trp, Ade, His). (B–D) Co-immunoprecipitation of flag-tagged IKK2 with myc-tagged JAB1/Csn5 (B), Csn4 (C) and Csn3 (D) after transient transfections of expression constructs in 293 cells as indicated in the headers. Anti-myc (upper panels) and anti-flag (lower panels) Western Blots of anti-flag immunoprecipitates (IP) and extracts are shown.

Fig 2.

FRET microscopy reveals interaction between IKK2 and JAB1/Csn5 in the cytosol. 293 cells were transfected with CFP and YFP separately (neg. control, CFP / YFP), a fusion protein of CFP and YFP (pos. control, CFP-YFP fusion), CFP-IKK2 in combination with either YFP-tagged full-length JAB1 (CFP-IKK2, YFP-JAB1) or YFP-tagged JAB1 N-terminal domain comprising the first 166 amino acids (CFP-IKK2, YFP-JAB1NT). Images were acquired with CFP-, YFP and raw-FRET filter sets and a pseudo-coloured corrected FRET image (FRETc) was calculated using ImageJ with the plug-in PixFRET [41].

Fig 3.

Interaction of endogenous JAB1/Csn5 with IKK2 in 293 cells. (A) Immunoprecipitation of the IKK-complex was carried out with anti-IKK2 antibodies (IKK) or an unrelated control antibody (con) as indicated in the header followed by immunoblot detection of IKK2 (upper panel) and JAB1 (lower panel) in immunoprecipitates (IP) and extracts as indicated. (B) Immunoprecipitation of the endogenous CSN complex with anti-Csn7 antibodies (Csn7) or unrelated control antibodies (con) followed by immunoblot detection of IKK2 (upper panel) and JAB1/Csn5 (lower panel). (C) Interaction of endogenous IKK-complexes with SCF-complexes. Cell extracts were subject to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-IKK2 and anti-NEMO antibodies (+) or unrelated control antibodies (–) followed by immunoblotting with anti-IKK2, Cullin-1 and βTrCP antibodies as indicated.

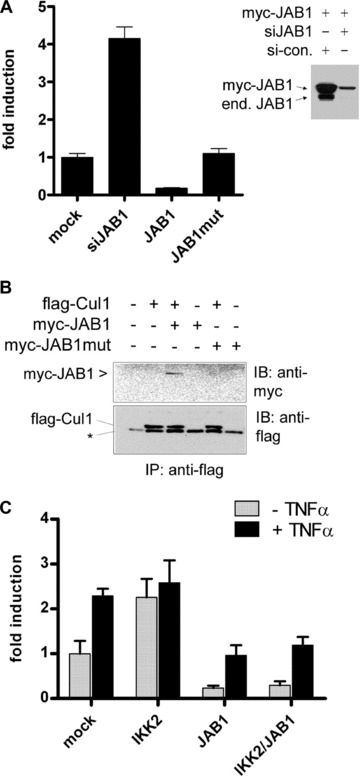

JAB1/Csn5 acts as negative regulator of NF-κB signalling

After identifying the interactions between the IKK complex, the SCFβTrCP-ubiquitination machinery and the CSN complex, we raised the question, whether they have a role in regulating NF-κB activity. Based on a report indicating that full ubiquitination activity of SCFβTrCP complexes requires a Nedd8-modification of Cullin-1 [10] and reports that CSN acts as a deneddylase of SCF-complexes with JAB1/Csn5 as the active component, we assumed that CSN might represent a negative regulator of IκBα ubiquitination in the context of the IKK/SCF-complex. This notion was supported by reporter gene assays for NF-κB activity, which revealed that ectopic expression of JAB1 significantly reduces basal NF-κB activity, while suppression of endogenous JAB1 by RNA interference leads to a prominent up-regulation (Fig. 4A). Control experiments with a non-targeting siRNA sequence verified the specificity of the gene suppression effect and proved that the vector backbone of the ectopic expression vector did not have any unspecific effect (Fig. S3). The influence of JAB1 on NF-κB activity was furthermore shown by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (Fig. S4) and by monitoring IκBα degradation in stable transfectants after addition of TNFα (Fig. S5). Inhibition of basal NF-κB activity by overexpression of JAB1 was dependent on a functional proteolytic motif within JAB1 (the MPN+ domain), since point mutations in this region essential for deneddylase activity, eliminated the inhibitory effect (Fig. 4A, 4th column). The important role of the proteolytic MPN+ domain of JAB1 was further strengthened by the observation that the JAB1 variant with the mutated MPN-domain could not interact with Cullin-1 (Fig. 4B). Testing the impact of ectopic expression of JAB1 on p53 activity revealed the opposite effect as compared to NF-κB activity in line with a counteractive role of these two transcription factors [44] (data not shown). Interestingly, inhibition of constitutive NF-κB activity by ectopic expression of JAB1 did not block a subsequent partial NF-κB-activation by TNFα (Fig. 4C).

Fig 4.

Effect of JAB1/Csn5 on NF-κB signalling. (A) NF-κB reporter gene assays after knock-down of JAB1 by RNA-interference (siJAB1) or after ectopic expression of wild-type JAB1 or mutant JAB1 (JAB1-MPN mutant). Basal NF-κB activity is shown as mean values ± SD from triplicates. The right panel shows the efficacy of the siRNA construct for knock-down of the endogenous, as well as ectopically expressed JAB1 as compared to a scrambled control-siRNA (si-con.). (B) Cullin-1 does not interact with a JAB1-variant comprising a mutation in the proteolytic MPN+ domain responsible for deneddylation and de-ubiquitination activity. Flag-tagged Cullin-1 (Flag-Cul1) was coexpressed with myc-JAB1, or mutant myc-JAB1 (JAB1-MPN mutant) in 293 cells followed by anti-flag immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of the myc-tag and Cullin-1 in immunoprecipitates (IP). The asterisk represents an unspecific band. (C) Reporter gene assay as in (A) including transfection with flag-IKK2 in the absence or presence of TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 6 hrs.

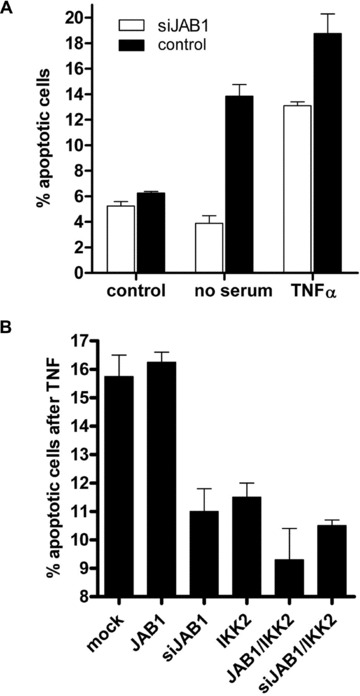

The effects observed after ectopic expression or gene suppression of JAB1 on NF-κB activity in reporter gene assays implies a potential role of JAB1/CSN in regulating biological processes downstream of NF-κB such as cell survival under stress. We tested this possibility by measuring the degree of apoptosis in stable transfectants after serum withdrawal or treatment with TNFα. Stable JAB1 knock-down cells were protected from apoptosis induced by these treatments suggesting that the higher constitutive NF-κB activity that is observed after gene suppression of JAB1 improves cell survival under stress (Fig. 5A). In transient transfection experiments, co-expression of IKK2 with JAB1 had a similar apoptosis-protecting effect as gene suppression of JAB1 (Fig. 5B). This indicates that an excess of IKK2 blocks the NF-κB inhibiting and pro-apoptotic effect of Csn5/JAB1 presumably via self-activation of IKK2 due to enforced expression. Another possible explanation is that IKK2 leads to enhanced degradation of JAB1 (as shown in Fig. 9E and Fig S7), which would then reduce its pro-apoptotic effect.

Fig 5.

Effect of JAB1/Csn5 on apoptosis. (A) Stable JAB1 knock-down cells (siJAB1) are protected from apoptosis induced by serum-withdrawal (24 h) or TNFα (50 ng/ml). The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined by flow cytometry staining with FITC-Annexin V. Data are mean values of triplicates; error bars reflect SD. (B) Apoptosis assay as in (A) after ectopic expression of the constructs indicated.

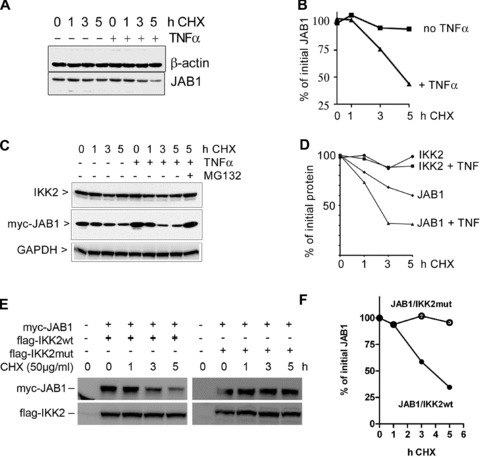

Fig 9.

Degradation of JAB1. (A) Degradation of endogenous JAB1 is accelerated after treatment with TNFα as assessed by immunoblotting of 293 cell extracts prepared after timed addition of cycloheximide. (B) Quantification of the JAB1 band shown in (A). (C) Enhanced degradation of ectopically expressed JAB1 but not IKK2 after addition of TNFα. Myc-tagged JAB1 was expressed in 293 cells and protein neo-synthesis was blocked for different time periods by addition of cycloheximide. TNFα (50 ng/ml) was added to one part of the samples. Cell extracts were analysed by immunoblotting for IKK2 and myc-JAB1. (D) Quantification of the Western Blot bands shown in (C). E, degradation of myc-JAB1 in presence of either wild-type IKK2 (flag-IKK2wt) or kinase-deficient mutant IKK2 (flag-IKK2mut) after blocking protein synthesis for different time periods with cycloheximide (CHX). (F) quantification of the myc-JAB1 bands shown in (E).

Interestingly, ectopic expression of JAB1 did not significantly increase apoptosis after addition of TNFα, presumably because it cannot fully block TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation (see also Fig. 4C). Although apoptosis might be regulated by other factors than NF-κB, it is well known that this transcription factor has a crucial role for cell survival by up-regulating anti-apoptotic genes and by counteracting p53 via induction of the p53-destabilizing molecule Mdm2 or competition for transcriptional cofactors [44].

Taken together, these observations suggest an important role of the IKK/SCF/CSN-axis for the regulation of apoptosis via NF-κB – and they indicate a biological role of JAB1/CSN as negative regulator of constitutive NF-κB activity and cell survival under stress.

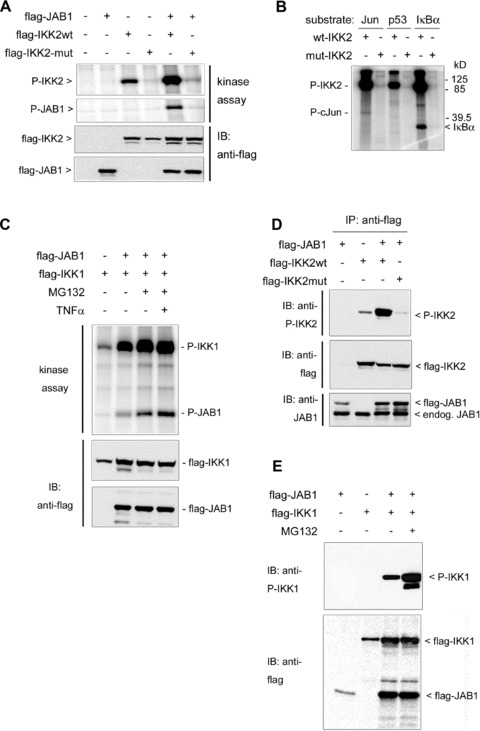

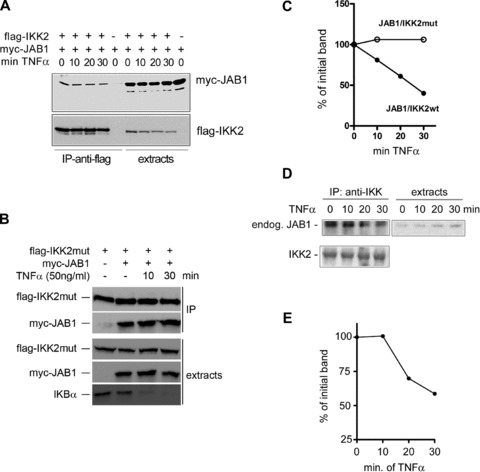

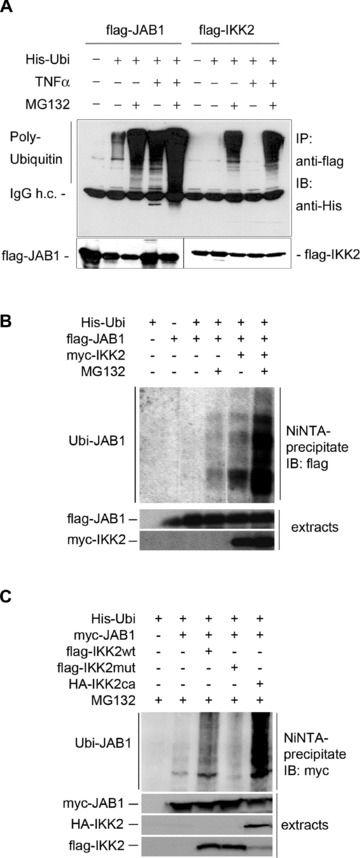

The IKK/CSN interaction affects phosphorylation and ubiquitination processes

The observed interaction between IKK2 and JAB1/Csn5 prompted us to test whether JAB1 can serve as substrate of IKK2. To this end, we performed in vitro kinase assays after co-immunoprecipitation of IKK2 and JAB1, which clearly demonstrated phosphorylation of JAB1 by IKK2 (Fig. 6A). Immunoprecipitated IKK2 was also capable of phosphorylating c-Jun, a known substrate of the originally postulated CSN-associated kinase [27], while we could not detect significant phosphorylation of p53 (Fig. 6B) – another substrate of a CSN-associated kinase. This supports the notion that different kinases can associate with the CSN complex. Interestingly, JAB1 could be phosphorylated not only by IKK2, but also by IKK1 as kinase (Fig. 6C). In vivo, the interaction between JAB1 and IKK2 or IKK1 caused a strikingly increased autophosphorylation of the respective IKK molecule (Fig. 6D and E) pointing at a bidirectional regulation. These data suggested that IKK-dependent phosphorylation of JAB1 might represent a regulatory mechanism for the association of IKK-molecules, the CSN complex and the ubiquitination machinery. This view was supported by the observation that JAB1/CSN dissociates from IKK2 rapidly after activation of the IKK-complex by TNFα (Fig. 7). Addition of TNFα to cells transfected with flag-tagged IKK2 and myc-tagged JAB1 followed by immunoprecipitation of the IKK2/JAB1 complex after different time points revealed a distinct dissociation of the complex within 10 to 20 min, when maximal activity of IKK2 is reached [3] (as also shown by kinetics of IκBα degradation in Fig. S6). The amount of JAB1 co-precipitated with IKK2 decreased significantly, while precipitated IKK2, as well as total JAB1 in the extracts remained constant (Fig. 7A and C). When JAB1 was co-transfected with a mutant IKK2 lacking kinase activity, addition of TNFα did not result in a decrease of JAB1 co-precipitated with IKK2 indicating that TNF-mediated dissociation of JAB1 and IKK2 requires the kinase activity of IKK2 (Fig. 7B and C). As with ectopically expressed wild-type IKK2 and JAB1, a clear dissociation was also observed for endogenous protein levels of non-transfected cells (Fig. 7D and E). These results are in line with our observation that ectopically expressed JAB1 cannot block TNFα-induced NF-κB activity in reporter gene assays (Fig. 4C) and they substantiate a model in which JAB1/CSN is a negative regulator of the SCF-ubiquitination activity that has to be released from the IKK/SCF-complex to achieve maximal ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα. This release might be triggered by the observed phosphorylation of Csn5/JAB1 by IKK2. Since phosphorylation of IκBα by IKK2 after TNFα-induced IKK2-activation initiates subsequent ubiquitination, we tested whether JAB1 is ubiquitinated as well in a TNFα-dependent manner. Using co-expression of His-tagged ubiquitin with flag-tagged JAB1 or IKK2, followed by anti-flag immunoprecipitation and Western blot detection of ubiquitin, we could clearly demonstrate ubiquitination of JAB1, which was enhanced by TNFα (Fig. 8A). In the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 we observed an accumulation of ubiquitinated JAB1 indicating that ubiquitinated JAB1 is degraded by proteasomes. Using flag-tagged IKK2 instead of JAB1 in combination with His-tagged ubiquitin revealed poly-ubiquitination of IKK2, which was just visible in the presence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132. However, this poly-ubiquitination was not enhanced by TNFα (Fig. 8A). Since TNFα triggers IKK2 activity, we next asked, whether ubiquitination of JAB1 depends on IKK2. To that end, we co-transfected JAB1 with wild-type IKK2 and His-tagged ubiquitin in absence or presence of MG132, followed by precipitation of His-tagged ubiquitin with NiNTA-resin and detection of JAB1 by Western Blotting. NiNTA-precipitation was performed in presence of the chaotropic agent guanidine hydrochloride, which prevents co-precipitation of non-covalently linked proteins. The subsequent immunoblot clearly revealed poly-ubiquitinated JAB1 (Fig. 8B). Moreover, poly-ubiquitination was enhanced in presence of IKK2, which was most clearly visible when proteasomal degradation was blocked by MG132. This finding was further strengthened by an additional experiment including mutant IKK2 lacking kinase activity (K44M mutant) and constitutive active IKK2 (S177E, S181E mutant). The constitutive active IKK2 strongly enhanced poly-ubiquitination of JAB1, whereas the kinase deficient IKK2 mutant clearly reduced JAB1 ubiquitination (Fig. 8C). The role of IKK2 for ubiquitination of JAB1 was furthermore supported by experiments using siRNA to suppress endogenous IKK2 (Fig. S7). We conclude that the poly-ubiquitination of JAB1 is triggered by IKK2 presumably via IKK2-mediated phosphorylation, as this process requires an active kinase domain of IKK2.

Fig 6.

Phosphorylation events in the IKK-CSN-complex. (A) Phosphorylation of Csn5/JAB1 by IKK2. Wild-type or mutant flag-IKK2 and flag-JAB1 were co-expressed in 293 cells, followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-flag beads and kinase assays as well as immunoblot analysis (anti-flag) of IKK2 and JAB1 expression. (B) Phosphorylation of c-Jun and IκBα by IKK2. Flag-tagged wild-type (wt) or mutant (mut) IKK2 was expressed in 293 cells, immunoprecipitated by anti-flag beads and kinase assays were performed as described in the ‘Materials and methods’ section using recombinant c-Jun, p53 (both from Biomol International, Inc., Hamburg, Germany) or GST-IκBα as substrates. A distinct phosphorylated band is visible for IκBα and a weaker band for c-Jun. (C) Phosphorylation of Csn5/ JAB1 by IKK1. 293 cells were transiently transfected with flag-tagged IKK1 and JAB1. MG132 was added to some samples to prevent proteasomal degradation. Anti-flag immunoprecipitates of cell extracts were subject to kinase assays and immunoblots against the flag-tag. JAB1-phosphorylation is most prominently visible in presence of MG132. (D) Auto-phosphorylation of IKK2 is enhanced by ectopically expressed JAB1. Flag-tagged wild-type or mutant IKK2 was coexpressed with flag-JAB1. Extracts were prepared 1 day after transfection and immunoblots were done for phospho-IKK2 (P-IKK2), flag and JAB1 as indicated. (E) Auto-phosphorylation of IKK1 is enhanced by ectopically expressed JAB1. Flag-tagged IKK1 and JAB1 were coexpressed and analysed as in (D). MG132 was added in one sample to block proteasomal degradation.

Fig 7.

Dissociation of the IKK/CSN complex after TNFα administration. (A) Activation of the NF-κB pathway with TNFα leads to rapid dissociation of JAB1 from IKK2. 293 cells were transfected with flag-IKK2 and myc-JAB1 as indicated. 1 day after transfection TNFα was added for different periods of time, followed by rapid cold extraction and immunoprecipitation with anti-flag-beads and Western Blot analysis of myc-JAB1 and flag-IKK2 as indicated. (B) JAB1 does not dissociate from a kinase-inactive IKK2 mutant (flag-IKK2-mut). The experiment was performed as in (A). (C) Quantification of the specific JAB1 immunoblot bands shown in A (JAB1/IKK2wt) and B (JAB1/IKK2mut). (D) Dissociation of endogenous JAB1 and thus the CSN complex from the IKK-complex after addition of TNFα. Non-transfected 293 cells were treated with TNFα followed by rapid extraction at the indicated time points. Endogenous IKK-complexes were immunoprecipitated with anti- IKK2 antibodies and immunoprecipitates (IP) as well as extracts were analysed by Western Blot for endogenous JAB1. (E) Quantification of the JAB1 band visible in (D).

Fig 8.

Ubiquitination of JAB1. (A) His-tagged ubiquitin was co-transfected with flag-JAB1 or flag-IKK2 as indicated followed by immunoprecipitation with anti-flag-beads and immunoblotting with anti-His- or anti-flag tag antibodies. A higher amount of ubiquitinated JAB1 or IKK2 was detected when the proteasome inhibitor MG132 was added. TNFα treatment (30 min, 50 ng/ml) resulted in increased ubiquitination. (B) ubiquitination of JAB1 was assessed after transfection with His-tagged ubiquitin and flag-tagged JAB1 in presence or absence of myc-tagged IKK2 and MG132. His-Ubiquitinated proteins were purified by NiNTA-resin under chaotropic conditions (including guanidine-HCl as described in the ‘Materials and methods’ section), preventing co-precipitation of non-covalently linked proteins. Bound His-ubiquitinated proteins were washed, followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-flag antibodies. (C) ubiquitination of JAB1 was analysed as in (A) with either wild-type IKK2 (flag-IKK2wt), kinase-deficient IKK2 mutant (flag-IKK2mut) or constitutive active IKK2 (HA-IKK2ca). Western blotting was carried out against the myc-tag of JAB1.

In order to study whether the TNFα-induced and IKK2-dependent poly-ubiquitination of JAB1 results in a reduced half life of the protein, we performed experiments in the presence of cycloheximide to block protein synthesis and to monitor protein turnover. This indicated that TNFα enhanced the degradation of endogenous JAB1 (Fig. 9A and B). Performing the experiment with ectopically expressed JAB1 revealed a similar result of enhanced degradation of JAB1 but not IKK2 after addition of TNFα (Fig. 9C and D). Next we wanted to answer the question, whether the regulation of the half-life of JAB1 involves IKK2 as TNFα-activated kinase.

To answer this question, we transfected 293 cells with myc-tagged JAB1 in combination with either wild-type or kinase-deficient mutant IKK2 followed by addition of cycloheximide to block protein synthesis. Cell extracts were prepared after different time points and the level of JAB1 quantified by immunoblotting. While JAB1 decreased readily in presence of wild-type IKK2, it remained stable in presence of the kinase-deficient mutant IKK2 (Fig. 9E and F).

Discussion

The first characterization of the CSN complex in human cells showed that it is associated with a kinase activity phosphorylating IκBα and p105-NF-κB molecules, as well as c-Jun [27]. However, a direct association of IKK2 with the CSN complex has not been shown so far, and other kinases, such as casein kinase II, protein kinase D and inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6-kinase have been postulated to be associated with the CSN complex [29, 30]. We have evidence that IKK2 represents another CSN associated kinase, which is furthermore associating with the SCFβTrCP E3 ligase ubiquitinating IκB molecules. An earlier hint for a potential physiological interaction between the IKK- and the CSN-complex was provided by a report showing that NEMO/IKKγ interacts with the CSN subunit Csn3 [43]. However, this interaction, which was identified in the yeast two-hybrid system, was not verified for endogenous, physiological protein levels and thus not for entire IKK- and CSN protein-complexes. Our findings that IKK2 interacts with at least three of the eight CSN components, Csn3, Csn4, and Csn5, leads us to the assumption that IKK2 associates with the whole CSN complex. This is further substantiated by immunoprecipitation experiments of endogenous IKK-signalosomes or CSN-complexes, which clearly show co-precipitation of components of the other complex. The CSN-complex is an important regulator of SCF-type E3-ligases and thus interacts with SCF-complexes. However, this regulation is intricate and still not completely understood. CSN inhibits SCF-ubiquitination activity in vitro by deneddylating and de-stabilizing SCF, while it is required for sustained activity of SCF-complexes in vivo. This is currently explained by a model, in which CSN mediates disassembly of SCF complexes containing inactive, auto-ubiquitinated components, such as F-box proteins, thereby allowing re-assembly and loading with new, active subunits [12, 20, 45]. The results of our experiments suggest the CSN complex as a negative regulator of NF-κB activation. Gene suppression of the CSN subunit JAB1/Csn5 augmented constitutive NF-κB activity, while ectopic expression of JAB1 reduced it. This is in line with a study of Csn5 function in Drosophila [32], where the authors showed that Csn5 null mutants had a constitutive nuclear localization of the NF-κB orthologue Dorsal although its activity was repressed by accumulated Cactus (the Drosophila IκB orthologue). The authors also showed an elevated basal NF-κB activity in human 293T cells after shRNA-mediated suppression of Csn5, while TNF-mediated activation was not significantly influenced, which is in line with our observations. It has to be noted though that the effect of Csn5/JAB1 on NF-κB seems to depend on the cell type and cellular context, as loss of JAB1 was also reported to reduce NF-κB activity, e.g. in thymocytes [46] or synovial fibroblasts of rheumatoid arthritis patients [47].

In our hands, mutation of the proteolytic MPN+ domain, which is capable of cleaving Nedd8 and perhaps also other ubiquitin- or ubiquitin-like moieties [22], prevented the NF-κB suppressive effect of JAB1, indicating that it acts either via deneddylation of the SCF-complex or via de-ubiquitination e.g. of IκBα or other molecules involved in the regulation of NF-κB. A similar but apparently different mechanism of a CSN-controlled deubiquitination of IκBα was recently postulated to be mediated by the CSN-associated deubiquitinase USP15 [31]. However, since knock down of endogenous JAB1/Csn5 increased basal activity of NF-κB in our experiments, and since mutation of the MPN+ domain of JAB1 prevented its inhibitory effect, we assume an important role of JAB1 itself in this regulatory process.

Taken together, our observations point at functionally important interactions between IKK-, SCF- and CSN-complexes. The tendency of the complexes involved in phosphorylation, ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα to interact with each other would explain the fast and efficient degradation of IκBα within a few minutes after activation of cells by TNFα. In this model, CSN acts as negative regulator of constitutive NF-κB activity, inhibiting constitutive SCF-mediated degradation of IκBα that might be triggered by a low basal activity of IKK2. Upon activation of the TNFα-signalling pathway, IKK2 is fully activated, phosphorylating not only IκB molecules but also JAB1/Csn5 and probably other components of the protein complexes involved. As a result, CSN dissociates from the super-complex, allowing rapid ubiquitination and degradation of IκBα and release of NF-κB. In addition to IκBα also JAB1 is poly-ubiquitinated dependent on IKK2 and degraded by proteasomes although with slower kinetics. Signal-induced association processes are certainly important for several steps of the NF-κB activation pathway such as recruitment of adapter proteins to cell surface receptors or activation of signalling kinases due to association with adapter proteins [44]. Our observations indicate that also dissociation events comprising negative regulators might have an important role in fine tuning basal and induced NF-κB activity. Our data of molecular interactions between the IKK-complex, the SCF-ubiquitination machinery and CSN as a negative regulator provide a plausible explanation for the rapid and efficient degradation of IκBα in the course of TNFα-mediated NF-κB activation. Furthermore our concept of a functional super-complex between IKK’s and the ubiquitination system would also account for the multifaceted mutual regulation that is found between the molecular machines that are responsible for phosphorylation, ubiquitination and degradation. It is evident that such a functional super-complex should not be seen as a rigid entity with a permanent association of the sub-components, but rather as a dynamic molecular machine subject to dissociation and re-assembly events and complex regulatory processes. The complexity of this system is also reflected by the diversity of roles that JAB1 or the CSN signalosome seem to have in a variety of diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [47], inflammatory disorders in general [48] atherosclerosis [49] or neurodegenerative diseases [50]. Moreover, JAB1 alone or in combination with the CSN complex have been reported to exert diverse functions in various forms of cancer, where they are involved in the degradation or stabilization of effector molecules such as oncogenes, tumour suppressor genes or cell cycle regulators [51]. The crosstalk of the JAB1/CSN-system with the IKK/NF-κB pathway that we describe in this study adds another level of complexity and brings in additional aspects of mutual regulation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the hospitality and the support by the Ghosh group and we also thank Wolfgang Dubiel for providing anti-Csn7 antibodies and Hongyong Fu for providing yeast two-hybrid constructs for all the CSN subunits. The project was mainly funded by the Competence Center Biomolecular Therapeutics, Vienna. Furthermore, we acknowledge the support by the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Max Kade foundation for funding a sabbatical of J.A.S. at the Immunobiology Section of Yale University Medical School and the support by the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Cancer Research, Vienna.

Supporting Information

Fig. S1 Interaction of IKK1 with JAB1/Csn5 and of NEMO with Csn3. 293 cells were transfected with expression constructs as indicated in the header followed by immunoprecipitation (IP: anti-flag) and immunoblot analysis of flag- and myc-tags in immunoprecipitates and extracts.

Fig. S2 Interaction between JAB1/Csn5 and Cullin-1: flag-tagged JAB1 and/or myc-tagged Cul-1 were transiently transfected in 293 cells followed by anti-flag immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of flag- and myc-tagged proteins in immunoprecipitates (IP) and extracts.

Fig. S3 Control experiments for vector backbones andspecificity of the siRNA. (A) 293 cells were transfectedwith myc-JAB1 in combination with the siRNA construct against JAB1(si-JAB1), a control siRNA construct with non-targeting sequence(si-scrambled), the empty expression vector construct (pcDNA3.1) orthe empty siRNA vector (si-vector). Myc-JAB1 expression wasassessed by immunoblotting. (B) the effect of theJAB1-targeting siRNA construct (si-JAB1) on expression ofendogenous JAB1 was compared to that of a non-targeting siRNAcontrol (si-scrambled) and control extracts.

Fig. S4 Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)showing the effect of JAB1 on NF-κB binding activity. 293cells were transfected with JAB1 expression or suppressionconstructs as indicated and compared to cells transfected with p65NF-κB. EMSA was performed as described in[33]. One lane was loaded with p65-transfectedextracts containing a 50-fold molar excess of the non-labelledNF-κB binding oligo-nucleotide as competitor (p65 +comp.). B, Quantification of the specific NF-κB bandsshown in (A).

Fig. S5 IκBα degradation in stable myc-JAB1and siJAB1 transfectants. Stable 293 transfectants of myc-JAB1 andsiJAB1 were generated by G418 selection of clones as described inthe ‘Materials and methods’ section. TNFα (50ng/ml) was added and cells were extracted after different timepoints, followed by immunoblot analysis of IκBαdegradation. The film is overexposed with respect to lanes 1 and 2(0 and 10 min TNFα) so to monitor the difference inIκBα degradation between 20 and 40 min after TNF addition.

Fig. S6 Kinetics of IκBα degradation asreadout for the fast activation of IKK2 following TNFαtreatment. 293 cells were treated for different periods of timewith TNFα, followed by rapid cell extraction and Western blotanalysis of IκBα. Degradation is already clearlyvisible at 10 min, indicating fast activation of the upstreamkinase IKK2 by TNFα.

Fig. S7 JAB1 protein levels and ubiquitination areaffected by IKK2. (A) 293 cells were transfected with flag-JAB1 and HA-tagged ubiquitin in combination with flag-IKK2 or genesuppression of IKK2 (si-IKK2). Extracts were subjected toimmunoprecipitation with anti-flag beads, followed by SDS-PAGE andimmunoblotting against flag and HA-tags. (B) quantificationof flag-JAB1 levels (control refers to lane 2 of A).(C) poly-ubiquitination of JAB1 was quantified by analysingthe HA-Ubi bands shown in (A) and normalization to totalflag-JAB1.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Schmid JA, Birbach A. IkappaB kinase beta (IKKbeta/IKK2/IKBKB)–a key molecule in signaling to the transcription factor NF-kappaB. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19:157–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercurio F, Zhu H, Murray BW, et al. IKK-1 and IKK-2: cytokine-activated IkappaB kinases essential for NF- kappaB activation. Science. 1997;278:860–6. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zandi E, Rothwarf DM, Delhase M, et al. The IkappaB kinase complex (IKK) contains two kinase subunits, IKKalpha and IKKbeta, necessary for IkappaB phosphorylation and NF-kappaB activation. Cell. 1997;91:243–52. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:225–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karin M, Lin A. NF-kappaB at the crossroads of life and death. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:221–7. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaron A, Hatzubai A, Davis M, et al. Identification of the receptor component of the IkappaBalpha-ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 1998;396:590–4. doi: 10.1038/25159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuchs SY, Chen A, Xiong Y, et al. HOS, a human homolog of Slimb, forms an SCF complex with Skp1 and Cullin1 and targets the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of IkappaB and beta-catenin. Oncogene. 1999;18:2039–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Read MA, Brownell JE, Gladysheva TB, et al. Nedd8 modification of cul-1 activates SCF(beta(TrCP))-dependent ubiquitination of IkappaBalpha. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2326–33. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2326-2333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawakami T, Chiba T, Suzuki T, et al. NEDD8 recruits E2-ubiquitin to SCF E3 ligase. EMBO J. 2001;20:4003–12. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cope GA, Deshaies RJ. COP9 signalosome: a multifunctional regulator of SCF and other cullin-based ubiquitin ligases. Cell. 2003;114:663–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00722-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei N, Deng XW. The COP9 signalosome. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:261–86. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.112449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwechheimer C, Deng X. COP9 signalosome revisited: a novel mediator of protein degradation. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:420–6. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bech-Otschir D, Seeger M, Dubiel W. The COP9 signalosome: at the interface between signal transduction and ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:467–73. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomoda K, Kubota Y, Kato J. Degradation of the cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 is instigated by Jab1. Nature. 1999;398:160–5. doi: 10.1038/18230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyapina S, Cope G, Shevchenko A, et al. Promotion of NEDD-CUL1 conjugate cleavage by COP9 signalosome. Science. 2001;292:1382–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1059780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cope GA, Suh GS, Aravind L, et al. Role of predicted metalloprotease motif of Jab1/Csn5 in cleavage of Nedd8 from Cul1. Science. 2002;298:608–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1075901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hetfeld BK, Helfrich A, Kapelari B, et al. The zinc finger of the CSN-associated deubiquitinating enzyme USP15 is essential to rescue the E3 ligase Rbx1. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1217–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wee S, Geyer RK, Toda T, et al. CSN facilitates Cullin-RING ubiquitin ligase function by counteracting autocatalytic adapter instability. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:387–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claret FX, Hibi M, Dhut S, et al. A new group of conserved coactivators that increase the specificity of AP-1 transcription factors. Nature. 1996;383:453–7. doi: 10.1038/383453a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groisman R, Polanowska J, Kuraoka I, et al. The ubiquitin ligase activity in the DDB2 and CSA complexes is differentially regulated by the COP9 signalosome in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2003;113:357–67. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukumoto A, Tomoda K, Kubota M, et al. Small Jab1-containing subcomplex is regulated in an anchorage- and cell cycle-dependent manner, which is abrogated by ras transformation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1047–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomoda K, Kato JY, Tatsumi E, et al. The Jab1/COP9 signalosome subcomplex is a downstream mediator of Bcr-Abl kinase activity and facilitates cell-cycle progression. Blood. 2005;105:775–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng Z, Shen Y, Feng S, et al. Evidence for a physical association of the COP9 signalosome, the proteasome, and specific SCF E3 ligases in vivo. Curr Biol. 2003;13:R504–5. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00439-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang X, Hetfeld BK, Seifert U, et al. Consequences of COP9 signalosome and 26S proteasome interaction. FEBS J. 2005;272:3909–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seeger M, Kraft R, Ferrell K, et al. A novel protein complex involved in signal transduction possessing similarities to 26S proteasome subunits. FASEB J. 1998;12:469–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bech-Otschir D, Kraft R, Huang X, et al. COP9 signalosome-specific phosphorylation targets p53 to degradation by the ubiquitin system. EMBO J. 2001;20:1630–9. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uhle S, Medalia O, Waldron R, et al. Protein kinase CK2 and protein kinase D are associated with the COP9 signalosome. EMBO J. 2003;22:1302–12. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun Y, Wilson MP, Majerus PW. Inositol 1,3,4-trisphosphate 5/6-kinase associates with the COP9 signalosome by binding to CSN1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45759–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schweitzer K, Bozko PM, Dubiel W, et al. CSN controls NF-kappaB by deubiquitinylation of IkappaBalpha. EMBO J. 2007;26:1532–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harari-Steinberg O, Cantera R, Denti S, et al. COP9 signalosome subunit 5 (CSN5/Jab1) regulates the development of the Drosophila immune system: effects on Cactus, Dorsal and hematopoiesis. Genes Cells. 2007;12:183–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebner K, Bandion A, Binder BR, et al. GMCSF activates NF-kappaB via direct interaction of the GMCSF receptor with IkappaB kinase beta. Blood. 2003;102:192–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oitzinger W, Hofer-Warbinek R, Schmid JA, et al. Adenovirus-mediated expression of a mutant IkappaB kinase 2 inhibits the response of endothelial cells to inflammatory stimuli. Blood. 2001;97:1611–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu H, Reis N, Lee Y, et al. Subunit interaction maps for the regulatory particle of the 26S proteasome and the COP9 signalosome. EMBO J. 2001;20:7096–107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Treier M, Staszewski LM, Bohmann D. Ubiquitin-dependent c-Jun degradation in vivo is mediated by the delta domain. Cell. 1994;78:787–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90502-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmid JA, Birbach A, Hofer-Warbinek R, et al. Dynamics of NF kappa B and Ikappa Balpha studied with green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins. Investigation of GFP-p65 binding to DNa by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17035–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000291200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birbach A, Gold P, Binder BR, et al. Signaling molecules of the NF-kappa B pathway shuttle constitutively between cytoplasm and nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10842–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webster GA, Perkins ND. Transcriptional Cross Talk between NF-kappa B and p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3485–95. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmid JA, Sitte HH. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer in the study of cancer pathways. Curr Opin Oncol. 2003;15:55–64. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feige JN, Sage D, Wahli W, et al. PixFRET, an ImageJ plug-in for FRET calculation that can accommodate variations in spectral bleed-throughs. Microsc Res Tech. 2005;68:51–8. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muratani M, Kung C, Shokat KM, et al. The F box protein Dsg1/Mdm30 is a transcriptional coactivator that stimulates Gal4 turnover and cotranscriptional mRNA processing. Cell. 2005;120:887–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong X, Xu L, Li X, et al. CSN3 interacts with IKKgamma and inhibits TNF- but not IL-1-induced NF-kappaB activation. FEBS Lett. 2001;499:133–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02535-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perkins ND. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf DA, Zhou C, Wee S. The COP9 signalosome: an assembly and maintenance platform for cullin ubiquitin ligases? Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:1029–33. doi: 10.1038/ncb1203-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panattoni M, Sanvito F, Basso V, et al. Targeted inactivation of the COP9 signalosome impairs multiple stages of T cell development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:465–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Li C, Liu Y, et al. JAB1 determines the response of rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts to tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:889–902. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kleemann R, Hausser A, Geiger G, et al. Intracellular action of the cytokine MIF to modulate AP-1 activity and the cell cycle through Jab1. Nature. 2000;408:211–6. doi: 10.1038/35041591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burger-Kentischer A, Goebel H, Seiler R, et al. Expression of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in different stages of human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1561–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012942.49244.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oono K, Yoneda T, Manabe T, et al. JAB1 participates in unfolded protein responses by association and dissociation with IRE1. Neurochemistry International. 2004;45:765–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richardson KS, Zundel W. The emerging role of the COP9 signalosome in cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:645–53. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Interaction of IKK1 with JAB1/Csn5 and of NEMO with Csn3. 293 cells were transfected with expression constructs as indicated in the header followed by immunoprecipitation (IP: anti-flag) and immunoblot analysis of flag- and myc-tags in immunoprecipitates and extracts.

Fig. S2 Interaction between JAB1/Csn5 and Cullin-1: flag-tagged JAB1 and/or myc-tagged Cul-1 were transiently transfected in 293 cells followed by anti-flag immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis of flag- and myc-tagged proteins in immunoprecipitates (IP) and extracts.

Fig. S3 Control experiments for vector backbones andspecificity of the siRNA. (A) 293 cells were transfectedwith myc-JAB1 in combination with the siRNA construct against JAB1(si-JAB1), a control siRNA construct with non-targeting sequence(si-scrambled), the empty expression vector construct (pcDNA3.1) orthe empty siRNA vector (si-vector). Myc-JAB1 expression wasassessed by immunoblotting. (B) the effect of theJAB1-targeting siRNA construct (si-JAB1) on expression ofendogenous JAB1 was compared to that of a non-targeting siRNAcontrol (si-scrambled) and control extracts.

Fig. S4 Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)showing the effect of JAB1 on NF-κB binding activity. 293cells were transfected with JAB1 expression or suppressionconstructs as indicated and compared to cells transfected with p65NF-κB. EMSA was performed as described in[33]. One lane was loaded with p65-transfectedextracts containing a 50-fold molar excess of the non-labelledNF-κB binding oligo-nucleotide as competitor (p65 +comp.). B, Quantification of the specific NF-κB bandsshown in (A).

Fig. S5 IκBα degradation in stable myc-JAB1and siJAB1 transfectants. Stable 293 transfectants of myc-JAB1 andsiJAB1 were generated by G418 selection of clones as described inthe ‘Materials and methods’ section. TNFα (50ng/ml) was added and cells were extracted after different timepoints, followed by immunoblot analysis of IκBαdegradation. The film is overexposed with respect to lanes 1 and 2(0 and 10 min TNFα) so to monitor the difference inIκBα degradation between 20 and 40 min after TNF addition.

Fig. S6 Kinetics of IκBα degradation asreadout for the fast activation of IKK2 following TNFαtreatment. 293 cells were treated for different periods of timewith TNFα, followed by rapid cell extraction and Western blotanalysis of IκBα. Degradation is already clearlyvisible at 10 min, indicating fast activation of the upstreamkinase IKK2 by TNFα.

Fig. S7 JAB1 protein levels and ubiquitination areaffected by IKK2. (A) 293 cells were transfected with flag-JAB1 and HA-tagged ubiquitin in combination with flag-IKK2 or genesuppression of IKK2 (si-IKK2). Extracts were subjected toimmunoprecipitation with anti-flag beads, followed by SDS-PAGE andimmunoblotting against flag and HA-tags. (B) quantificationof flag-JAB1 levels (control refers to lane 2 of A).(C) poly-ubiquitination of JAB1 was quantified by analysingthe HA-Ubi bands shown in (A) and normalization to totalflag-JAB1.