Abstract

The purpose of this study was to analyze the performance of a porcine-derived acellular dermal matrix (Strattice Reconstructive Tissue Matrix) in patients at increased risk for perioperative complications. We reviewed medical records for patients with complex abdominal wall reconstruction (AWR) and Strattice underlay from 2007 to 2010. Intermediate-risk patients were defined as having multiple comorbidities without abdominal infection. Forty-one patients met the inclusion criteria (mean age, 60 years; mean body mass index, 35.5 kg/m2). Comorbidities included coronary artery disease (63.4%), diabetes mellitus (36.6%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17.1%). Fascial closure was achieved in 40 patients (97.6%). Average hospitalization was 6.4 days (range, 1–24 days). Complications included seroma (7.3%), wound dehiscence with Strattice exposure (4.9%), cellulitis (2.4%), and hematoma (2.4%). All patients achieved abdominal wall closure with no recurrent hernias or need for Strattice removal. Patients with multiple comorbidities at intermediate risk of postoperative complications can achieve successful, safe AWR with Strattice.

Keywords: Abdominal wall reconstruction, Acellular dermal matrix, Comorbidities, Herniorrhaphy, Strattice

Abdominal wall reconstruction (AWR) in the setting of ventral abdominal hernias has historically been considered complex and associated with high recurrence and poor outcomes. With the evolution of advanced surgical techniques and the use of various mesh products, repair of these complex abdominal hernias has been facilitated. Despite these advancements, patient comorbidities, variability in hernia complexity, and inappropriate application of mesh products continue to negatively impact AWR outcomes.

This past decade has been characterized with an expansion of both synthetic and biologic materials. Advances in such technology offer surgeons many options for mesh selection in AWR; however, identifying the appropriate patient population to receive each reconstructive material remains unclear. Traditionally, synthetic mesh repair has been used in many patients and has demonstrated a reduction in recurrence compared with suture repair.1–5 Although commonly used in the repair of ventral hernias, the use of synthetic mesh is considered contraindicated in contaminated cases primarily because of the increased risk for infection, prolonged hospitalization, and mesh removal.6–8

Strattice Reconstructive Tissue Matrix (LifeCell Corporation; Branchburg, New Jersey) is a non-cross-linked porcine-derived acellular dermal matrix (PADM) that, along with other acellular dermal matrices (ADMs), has demonstrated efficacy in the reinforcement of AWR. Moreover, these biologic meshes have facilitated successful AWR in the setting of infection.9–20 Yet, these studies have included a heterogeneous patient population with variable comorbidities and hernia grades leading to a sundry of complication profiles and outcomes.21–23

A hernia grading system has been introduced to allow for more accurate reporting of outcomes. Hernia grading has been previously published and is determined by patient factors and hernia factors including comorbidities, history of mesh infections, and/or active infection.24 In intermediate-risk patients (grades 2 and 3), complication rates remain high in comparison to patients with fewer comorbidities.23,25–27 Strattice has been studied prospectively in the Repair of Infected or Contaminated Hernias (RICH) trial for high-risk patients; however, no study to date has examined the success of biologic mesh for intermediate-risk patients.28 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the efficacy of Strattice mesh in AWR for intermediate-risk patients by analyzing hernia recurrence and 30-day postoperative morbidity.

Methods

A retrospective review of a prospectively maintained AWR database was conducted of all patients who underwent AWR by the senior author (PB) from 2007 to 2010. Patients who underwent AWR with Strattice mesh for grade 2 or 3 hernia, based upon the Ventral Hernia Working Group criteria, were identified. Patient demographics, preoperative, and postoperative course were reviewed for each patient. All complications within the first 30 days following surgery were considered.

Perioperative period

All patients received perioperative prophylactic antibiotics prior to and after AWR. A standard midline surgical approach was used for all patients, and bilateral subcutaneous flaps were elevated above the anterior fascia. Perforating vessels to the adipocutaneous layer were preserved when possible during the dissection. A complete lysis of adhesions was performed when necessary, and all previously implanted synthetic material was removed. A component separation procedure was performed where appropriate in order to obtain a tension-free midline closure with approximation of the rectus abdominis muscles. The Strattice was placed in an intraperitoneal, underlay fashion using vertical mattress No. 1 polydioxanone (PDS) suture to keep an approximately 5-cm overlap of mesh. Once the mesh was secured in place, the wound was irrigated, and the midline fascia was closed using figure-eight No. 1 PDS sutures. Two No. 10 Jackson Pratt drains were placed overlying the fascia, brought through separate stab incisions in each of the lower quadrants, and secured to the skin using 3-0 nylon sutures. The wound was then closed in a layered fashion with skin staples. In patients with a moderate to large abdominal pannus, a panniculectomy was performed using a horizontal, vertical, or fleur-de-lis design.

Postoperative period

All patients were administered 24 hours of perioperative antibiotics, maintained on appropriate deep vein thrombosis (DVT) thromboprophylaxis, and discharged from the hospital following ileus resolution. All patients were evaluated postoperatively on an outpatient basis at 2 weeks and 4 weeks by the primary surgeon (PB). After this time frame, patients were seen in clinic as needed for their particular care with an average follow-up of 445 days (range, 176–648 days). Office charts were reviewed for details of each patient's postoperative course. Drain removal occurred in all patients when output reached below 30 mL/d. An abdominal binder was maintained for each patient for approximately 4 weeks following surgery.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS for Windows, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Categorical demographic variables were analyzed via Fisher exact test. Means were calculated for continuous variables and were compared via 2-sample t tests. An a priori P value of 0.05 was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

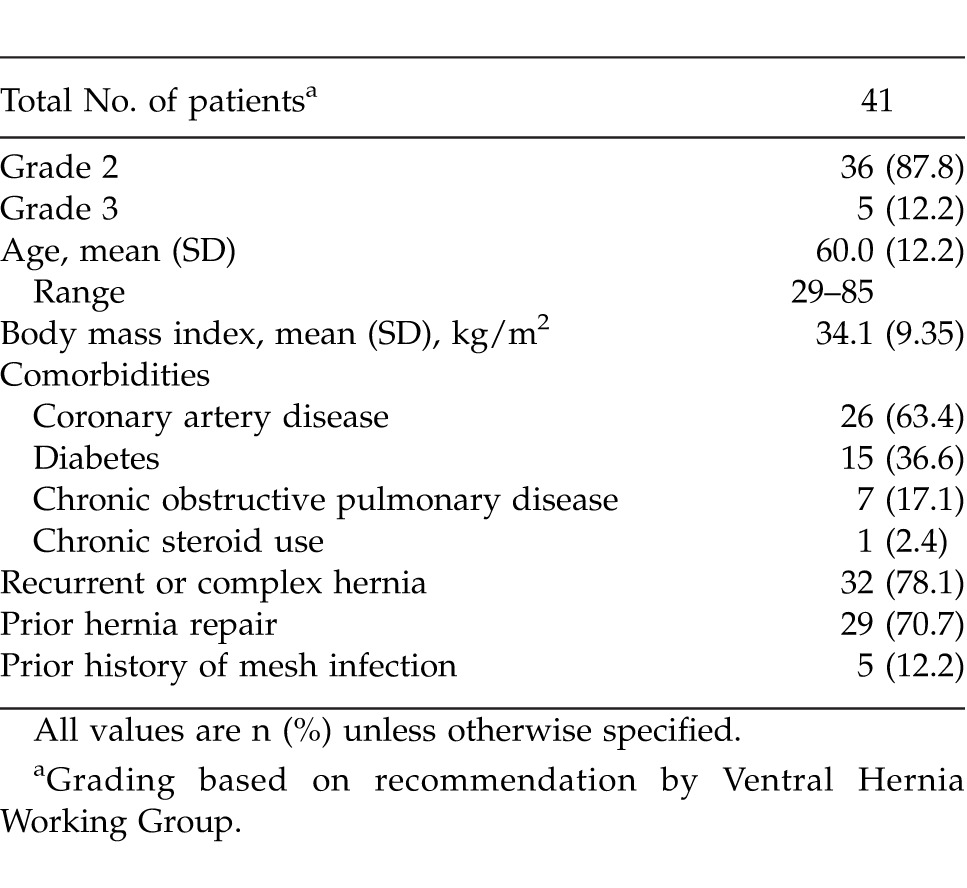

From 2007 to 2010, 69 patients underwent AWR using Strattice mesh by the primary surgeon (PB). Of this cohort, 41 patients met the study criteria (Table 1); 87.8% of patients were classified as grade 2 and 12.2% as grade 3 ventral hernia. The average patient age was 60 years (range, 29–85 years) with a body mass index of 35.5 kg/m2 (range, 19.8–51.5 kg/m2). Patient comorbidities included coronary artery disease (63.4%), diabetes mellitus (36.6%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17.1%). Chronic steroid use was noted in a single patient (2.4%). Recurrent/complex hernia was present in 32 of 41 patients (78%). A history of a prior mesh-related infection was noted in 5 of 41 patients (12.2%). Mean diameter of the cumulative defects was 13.7 cm (range, 5–30 cm), and there was an average of 1.2 defects per patient (range, 1–4 defects).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and background information

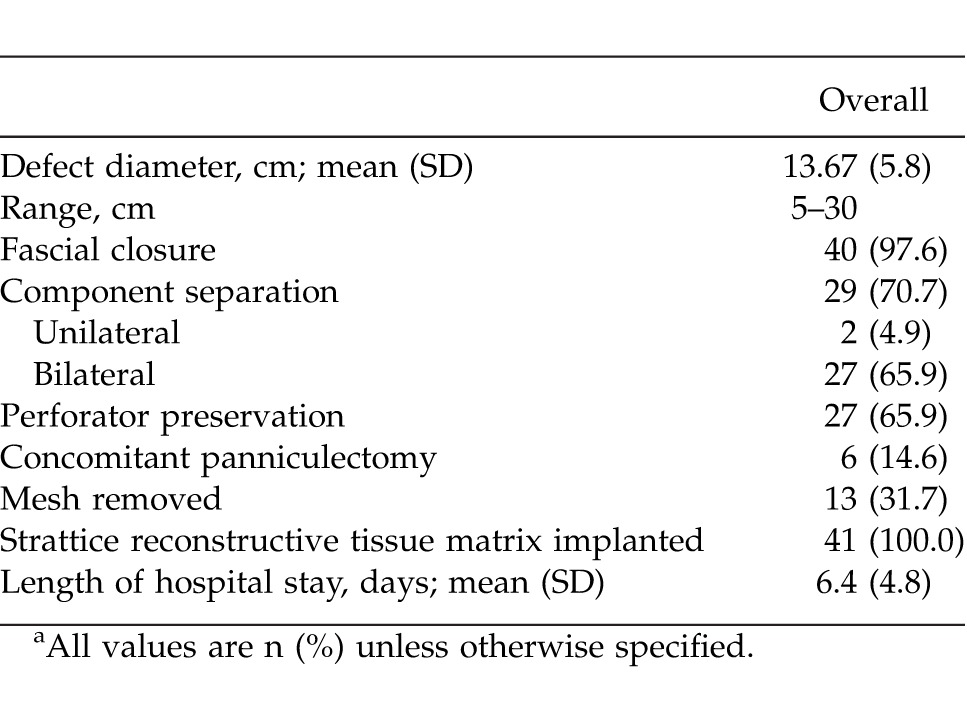

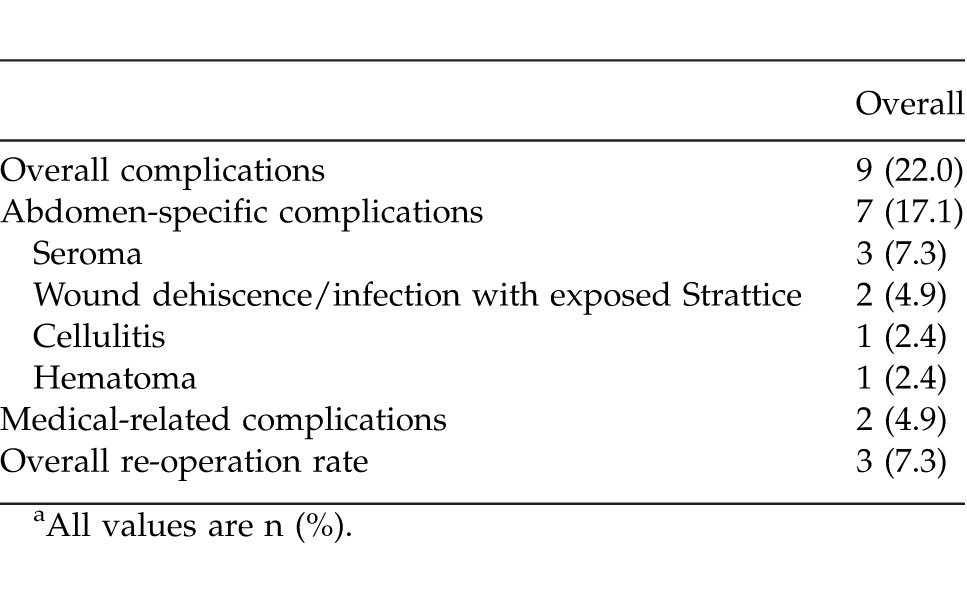

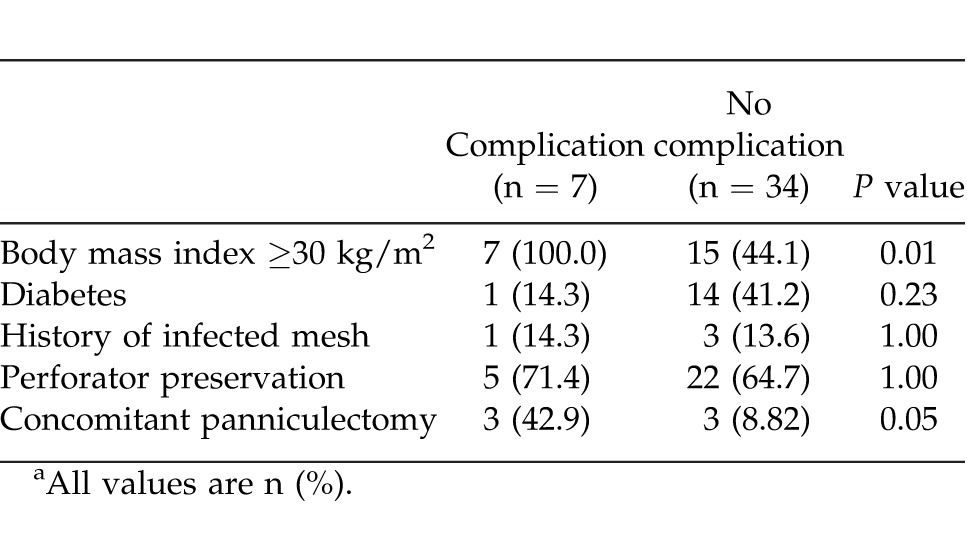

Primary fascial closure was achieved in 40 of 41 patients (97.6%) (Table 2). Perforator preservation was attempted in all patients and was achieved in 27 of 41 patients (65.9%). A concomitant panniculectomy was performed in 6 of 41 patients (14.6%). Following repair, the average hospital stay was 6.4 days (range, 1–24 days). Overall complication rate was 22.0% (Table 3). Abdomen-specific complications occurred in 17.1% of patients and included seroma (3 of 41 patients; 7.3%), wound dehiscence with Strattice exposure (2 of 41 patients; 4.9%), cellulitis (1 of 41 patients; 2.4%), and hematoma (1 of 41 patients; 2.4%). Of all abdomen-specific complications, 3 of 7 (42.9%) occurred in patients who had concomitant panniculectomy. The overall re-operation rate was 7.3% (3 of 41 patients) within the first 30 days postoperatively for evacuation of hematoma (1 patient) and debridement and closure (2 patients). A body mass index above 30 kg/m2 was found to be a predictive factor of postoperative complications (P < 0.05), while concomitant panniculectomy approached significance (P = 0.05) (Table 4). Medical complications occurred in 2 patients (4.9%) during the postoperative period; 1 patient was diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism requiring anticoagulation therapy, and 1 patient had postoperative myocardial infarction requiring cardiac intervention. No patients required removal of Strattice, all patients achieved wound closure, and there were no cases of hernia recurrence through patient follow-up to date (average of 445 days; range, 176–648 days). Negative-pressure wound therapy (VAC) was used to facilitate delayed wound closure in 2 patients that had wound infections with Strattice exposure, and 1 patient subsequently required skin grafting for definitive soft-tissue closure.

Table 2.

Operative detailsa

Table 3.

Thirty-day complication rate following Strattice implantationa

Table 4.

Factors associated with complicationsa

Discussion

The variability in patient demographics can dramatically influence patient outcomes following hernia repair. Stratifying patients based on comorbidities and the grade of their hernia allows for the development of clinical algorithms that can then be used as reliable outcome predictors following surgery. The Ventral Hernia Working Group has proposed a classification to anticipate surgical outcomes.24 Relatively healthy patients (grade 1) with primary hernias will likely have successful outcomes with the use of any mesh employed.1,3 However, patients with comorbidities (grade 2/3) and recurrent hernias can be challenging and may require newer, biologic mesh agents.

Biologic meshes are an essential component of a surgeon's armamentarium in regard to complex AWR. Their effectiveness is demonstrated by their use in patients with infected surgical fields for which synthetic meshes are relatively contraindicated. Furthermore, non-cross-linked PADM has been shown to have mesh-musculofascial interface strength similar to the native abdominal wall.29 Compared with synthetic mesh or cross-linked biologic mesh, non-cross-linked PADM allows tissue remodeling rather than encapsulation with scar tissue.30

Multiple studies have investigated outcomes following ADM implantation for AWR. Pomahac and Aflaki found that 1 of 16 patients required ADM removal following wound infection.21 Similarly, Patton et al found that only 3% of patients required ADM removal in contaminated fields.16 In addition, longer-term studies highlight decreased recurrence rates with the use of ADM in conjunction with musculofascial advancement.22,31 No patients in our study required removal of Strattice following open wounds and PADM exposure. The 2 patients who developed incision dehiscence and biologic mesh exposure were treated with operative debridement and negative-pressure wound therapy until either delayed primary wound closure was achieved (1 patient) or the wound bed was ready for skin grafting (1 patient). In the current medical climate of increasing expectations, the role of patient-related comorbidities on surgical outcomes cannot be overlooked. Clearly, AWR in the setting of comorbidities is associated with increased complications.32–34 For an obese patient population, Moore et al found that wound-related complications occurred in approximately 20% of patients following AWR.27 Furthermore, Candage et al describe wound-related complications in 54% of patients with multiple comorbidities; however, this includes grade-4 hernia patients with infected or contaminated wounds.35 The current literature does not provide clear evidence regarding mesh selection for grade 2 or 3, intermediate-risk abdominal hernia patients. The senior author selected a biologic mesh to minimize complications in a patient population with multiple medical comorbidities given the likelihood of a failed prosthetic reconstruction; 78% of patients presented with a recurrent hernia and 12% already had an infected previous prosthetic mesh reconstruction. Although the wound-related complication rate in our series was approximately 1 in 6 patients, most could be managed successfully with conservative therapy. In the current medical climate of financial constraints, it is unreasonable to indiscriminately utilize expensive products in the face of less-expensive alternatives. Still, this study demonstrates a 4.9% incidence of wound dehiscence and Strattice exposure for this intermediate-risk population with no patients requiring explantation of mesh. The presence of a biologic mesh mitigated the financial burden associated with subsequent foreign body removal, staged reconstruction, and corresponding hospitalizations that would be standard of care in the setting of a prosthetic mesh. In the setting of these more complex AWRs, the cost of biologic mesh may be justified.

Preoperative hernia classification and patient selection are paramount to the development of postsurgical complications and successful AWR. Reinforcement of the abdominal repair in the patient at intermediate risk for recurrence with Strattice ADM has demonstrated to be stable, successful, and safe with acceptable short-term morbidity. Strattice appears to be clinically well tolerated and provides support to the abdominal wall in patients at intermediate risk for postoperative complications.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Peloton Advantage, LLC, Parsippany, New Jersey, and was funded by LifeCell Corporation. Drs Bhanot and Nahabedian are members of the Speakers Bureau for LifeCell Corporation; Branchburg, New Jersey.

References

- 1.Burger JW, Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, Halm JA, Verdaasdonk EG, Jeekel J. Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of suture versus mesh repair of incisional hernia. Ann Surg. 2004;240(4):578–583. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141193.08524.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko JH, Salvay DM, Paul BC, Wang EC, Dumanian GA. Soft polypropylene mesh, but not cadaveric dermis, significantly improves outcomes in midline hernia repairs using the components separation technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(3):836–847. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b0380e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luijendijk RW, Hop WC, van den Tol MP, de Lange DC, Braaksma MM, IJzermans JN, et al. A comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(6):392–398. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berrevoet F, Fierens K, De Gols J, Navez B, Van Bastelaere W, Meir E, et al. Multicentric observational cohort study evaluating a composite mesh with incorporated oxidized regenerated cellulose in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2009;13(1):23–27. doi: 10.1007/s10029-008-0418-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen MJ. Polyester-based mesh for ventral hernia repair: is it safe? Am J Surg. 2009;197(3):353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alaedeen DI, Lipman J, Medalie D, Rosen MJ. The single-staged approach to the surgical management of abdominal wall hernias in contaminated fields. Hernia. 2007;11(1):41–45. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finan KR, Vick CC, Kiefe CI, Neumayer L, Hawn MT. Predictors of wound infection in ventral hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2005;190(5):676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blatnik JA, Harth KC, Aeder MI, Rosen MJ. Thirty-day readmission after ventral hernia repair: predictable or preventable? Surg Endosc. 2011;25(5):1446–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EI, Chike-Obi CJ, Gonzalez P, Garza R, Leong M, Subramanian A, et al. Abdominal wall repair using human acellular dermal matrix: a follow-up study. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5):650–657. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasajpour H, LeBlanc KA, Steele MH. Complex hernia repair using component separation technique paired with intraperitoneal acellular porcine dermis and synthetic mesh overlay. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66(3):280–284. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181e9449d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah BC, Tiwari MM, Goede MR, Eichler MJ, Hollins RR, McBride CL, et al. Not all biologics are equal! Hernia. 2011;15(2):165–171. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chavarriaga LF, Lin E, Losken A, Cook MW, Jeansonne LO, White BC, et al. Management of complex abdominal wall defects using acellular porcine dermal collagen. Am Surg. 2010;76(1):96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wietfeldt ED, Hassan I, Rakinic J. Utilization of bovine acellular dermal matrix for abdominal wall reconstruction: a retrospective case series. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2009;55(8):52–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz JJ, Jr, Guy J, Berkes MB, Guillamondegui O, Miller RS. Acellular dermal allograft for ventral hernia repair in the compromised surgical field. Am Surg. 2006;72(12):1181–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim H, Bruen K, Vargo D. Acellular dermal matrix in the management of high-risk abdominal wall defects. Am J Surg. 2006;192(6):705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patton JH, Jr, Berry S, Kralovich KA. Use of human acellular dermal matrix in complex and contaminated abdominal wall reconstructions. Am J Surg. 2007;193(3):360–363. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taner T, Cima RR, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG. Surgical treatment of complex enterocutaneous fistulas in IBD patients using human acellular dermal matrix. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(8):1208–1212. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavallaro A, Lo Menzo E, Di Vita M, Zanghi A, Cavallaro V, Veroux PF, et al. Use of biological meshes for abdominal wall reconstruction in highly contaminated fields. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(15):1928–1933. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i15.1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parker DM, Armstrong PJ, Frizzi JD, North JH., Jr Porcine dermal collagen (Permacol) for abdominal wall reconstruction. Curr Surg. 2006;63(4):255–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byrnes MC, Irwin E, Carlson D, Campeau A, Gipson JC, Beal A, et al. Repair of high-risk incisional hernias and traumatic abdominal wall defects with porcine mesh. Am Surg. 2011;77(2):144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pomahac B, Aflaki P. Use of a non-cross-linked porcine dermal scaffold in abdominal wall reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2010;199(1):22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolker AR, Brown DJ, Redstone JS, Scarpinato VM, Wallack MK. Multilayer reconstruction of abdominal wall defects with acellular dermal allograft (AlloDerm) and component separation. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(1):36–41. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000168248.83197.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghazi B, Deigni O, Yezhelyev M, Losken A. Current options in the management of complex abdominal wall defects. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66(5):488–492. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31820d18db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breuing K, Butler CE, Ferzoco S, Franz M, Hultman CS, Kilbridge JF, et al. Incisional ventral hernias: review of the literature and recommendations regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery. 2010;148(3):544–558. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunne JR, Malone DL, Tracy JK, Napolitano LM. Abdominal wall hernias: risk factors for infection and resource utilization. J Surg Res. 2003;111(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(03)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sailes FC, Walls J, Guelig D, Mirzabeigi M, Long WD, Crawford A, et al. Synthetic and biological mesh in component separation: a 10-year single institution review. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):696–698. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181dc8409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore M, Bax T, MacFarlane M, McNevin MS. Outcomes of the fascial component separation technique with synthetic mesh reinforcement for repair of complex ventral incisional hernias in the morbidly obese. Am J Surg. 2008;195(5):575–579. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itani KMF, Rosen M, Vargo D, Awad SS, DeNoto G, Butler CE, et al. Prospective study of single-stage repair of contaminated hernias using a biologic porcine tissue matrix: the RICH study. Surgery. 2012;152(3):498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melman L, Jenkins ED, Hamilton NA, Bender LC, Brodt MD, Deeken CR, et al. Early biocompatibility of crosslinked and non-crosslinked biologic meshes in a porcine model of ventral hernia repair. Hernia. 2011;15(2):157–164. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0770-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Butler CE, Burns NK, Campbell KT, Mathur AB, Jaffari MV, Rios CN. Comparison of cross-linked and non-cross-linked porcine acellular dermal matrices for ventral hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(3):368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, de la Torre JI, Marrero I, Andrades P, Davis MR, Vasconez LO. Utilization of human cadaveric acellular dermis for abdominal hernia reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58(3):264–267. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000254410.91132.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin HJ, Spoerke N, Deveney C, Martindale R. Reconstruction of complex abdominal wall hernias using acellular human dermal matrix: a single institution experience. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, Jr, Reines HD, DeMaria EJ, Newsome HH, Lowry JW. Greater risk of incisional hernia with morbidly obese than steroid-dependent patients and low recurrence with prefascial polypropylene mesh. Am J Surg. 1996;171(1):80–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bueno Lledó J, Sosa Quesada Y, Gómez i Gavara I, Vaqué Urbaneja J, Carbonell Tatay F, Bonafé Diana S, et al. Prosthetic infection after hernioplasty. Five years experience. Cir Esp. 2009;85(3):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Candage R, Jones K, Luchette FA, Sinacore JM, Vandevender D, Reed RL. Use of human acellular dermal matrix for hernia repair: friend or foe? Surgery. 2008;144(4):703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]