Abstract

Background

Migraine is a prevalent disease which is classified into two groups of migraine with aura and without aura. Eighteen percent of women and 6.5 percent of men in United States have migraine headache. Migraine headache is prevalent in all age groups but it usually subsides in adults above fifty. Migraine has many risk factors such as stress, light, tiredness, special foods and beverages. The aim of this study was the evaluation of the effects of body mass index (BMI) on the treatment of migraine headaches.

Methods

All patients assigned to four groups according to their BMI. Patients with more than three attacks per month received nortriptyline and propranolol for eight weeks. The frequency, duration and severity of pain were measured by visual analogue scale (VAS) and behavioral rating scale (BRS-6) in regular intervals.

Results

203 patients completed the study. 153(75%) subjects were women and 50(25%) were men. Mean age of patients was 30.5 ± 7.1 years. Mean weight was 80.4 ± 14.1 kg and mean height was 1.67 ± 0.07 m. Pain frequency and duration showed statistically significant differences among four groups with better response in patients with lower BMI (P < 0.0001). VAS and BRS-6 scales showed statistically significant differences among four groups in favor of patients with lower BMI (P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

This study showed that obesity has a direct influence on the treatment of migraine headaches. It could be recommended to patients to reduce their weight for better response to treatment. In addition, care should be taken about migraine drugs which make a tendency for increased appetite.

Keywords: Migraine, Body Mass Index, Visual Analogue Scale

Introduction

Migraine is a periodic, often pulsatile unilateral headache, which is common in all ranges of ages.1, 2 Migraine headaches usually begin in the early adulthood although it can begins as late as fifth decade of life.1, 3–5 There are two types of syndrome, migraine with aura and without aura. The ratio of these two types of migraine is 1:5.6–9 In genetic studies, a Mendelian pattern was not observed in both types of migraine but familial occurrence is common in both types and especially in patients with aura.10, 11 Migraine is a common disorder and prevalence of it is approximately 6.5 percent in men and 18 percent in women.

In many women, migraine attacks tend to occur in premenstrual period and in some women migraine attacks occur solely in this period.12, 13 Episodes of headaches usually persists 4–72 hours and nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia and fatigue are common symptoms that are usually observed in this disorder.7, 14–17 Pain is usually severe and needs treatment with analgesics and sometimes bed rest is necessary. Migraines have many risk factors, some patients experience severe attacks after especial foods such as cheese, chocolate, onion or especial foods rich in tyramine. Alcohol, cigarette smoking, and sun exposure are other risk factors.18–24

Obesity is a serious problem in our life which is growing more and more specially in city dwellers. Obesity has lots of complications such as heart failure, sudden death, early fatigue ability and osteoarthritis.25–28 Many methods are used for migraine headaches treatment such as chemical drugs, psychotherapy, injection of botulinum toxin, behavioral modifications, psychotherapy, chiropractic, acupuncture and biofeedback techniques. Some of these treatments are not accepted by all experts but there is consensus upon drugs.22, 24, 29–32 Treatment are divided into two phases, acute treatment of pain and preventive treatment. In the first phase, we usually use analgesics (NSAIDS), serotonin agonists and ergots derivatives and in the second phase the most preferred drugs are beta blockers, tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants.3, 30, 31, 33–35

Migraine is very important disease with high prevalence which makes many patients to spend a lot of time in bed for resting. Although there are many various treatments, some of them are not tolerated in all patients. Further investigation is recommended to find better options for the treatment of migraine headaches. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of weight on the preventive treatment of migraine headaches.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective experimental study conducted on 203 patients who were referred for evaluation of headache to the neurology clinic in the period from 2009 to 2010. All cases were selected randomly. Subjects were categorized in four groups according to their body mass index (BMI), < 24.9, 24.9-29, 29-34.9 and >35. After the description of methods and aims of study all patients who had more than 3 episodes of migraine headaches each month and voluntarily asked for preventing treatment were selected for study.

All patients were adults between 18 to 45 years old who had migraine headaches according to International headache society criteria (IHS). Visual analogue scale (VAS) and 6-point behavioral rating scale (BRS-6) were two standard international scales which were used for evaluation of the severity of pain. BRS-6 is a standard score for pain based on clinical symptoms which is divided from 0 to 5. Higher scores show more severe pain.

All patients were evaluated for the frequency, duration and severity of pain in the beginning of study and at the end of 4th, 6th and 8th weeks. Selected patients were treated with nortriptyline 0.6 mg/kg/d and propranolol 1mg/kg/d. Dosage was increased gradually over four weeks from the beginning of study to the end of 4th week. If there was any drug reaction or complication, treatment was discontinued. Individuals who had any contraindication for use of these drugs were not included in this study. Data were recorded an analyzed with SPSS software version 16. This study was a dissertation supported by Shahed University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

There were 153 (75%) women and 50 (25%) men. Mean age of the patients was 30.5 ± 7.1 years ranged from 15 to 45 years. Weight, height and BMI of participants were 80.4 ± 14.1 kg, 1.67 ± 0.07 meter and 28.5 ± 4.1, respectively.

Pain frequency decreased from 8.1 ± 2.3 attacks per month at baseline to 2.9 ± 2.6 attacks per month in 8th week. Pain duration decreased from 16.1 ± 6.1 hour at baseline to 11.7 ± 5.2, 7.2 ± 5.8 and 6.6 ± 5.8 in 4th, 6th and 8th weeks, respectively. VAS also showed a decreasing pattern from 73.3 ± 15.2 mm in 1st week to 56.8 ± 16.2 mm, 40.3 ± 20.9 mm and 32.7 ± 23.9 mm in 4th, 6th and 8th weeks, respectively. BRS-6 was 3.43 ± 1.04 in 1st week. It reduced to 2.72 ± 1.04 in 4th week, 1.84 ± 1.07 in 6th week and 1.40 ± 1.20 in 8th week.

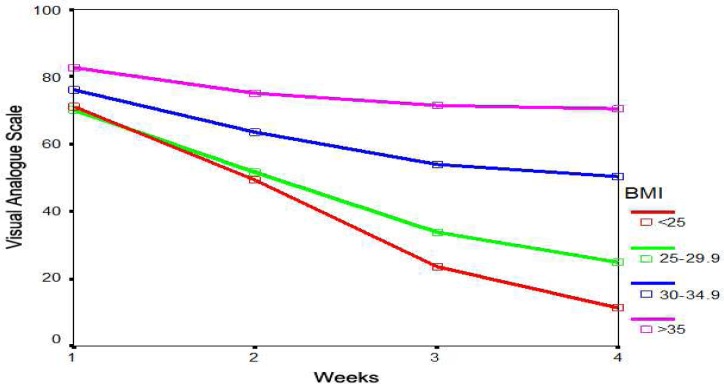

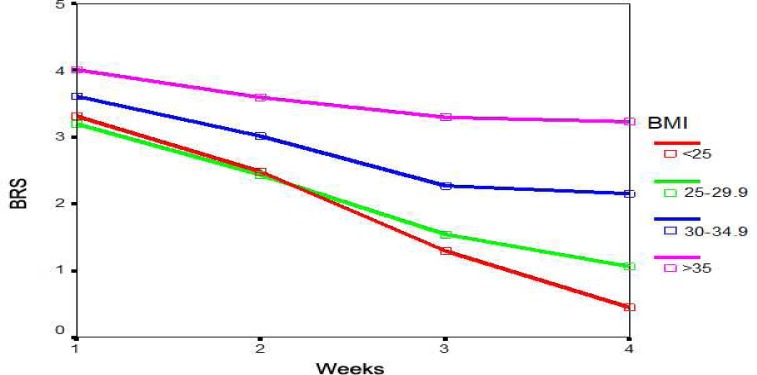

Different demographic characteristic of patients, pain duration, frequency and severity of pain measured with VAS and BRS-6 scales are summarized in Tables 1 to 3. Diagrams 1 and 2 show VAS and BRS-6 values in BMI groups.

Table 1.

Pain frequency and duration in different body mass index groups throughout the study period

| BMI | Pain frequency (attack/month) | Pain duration (hours) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st day | 8th week | 1st day | 4th week | 6th week | 8th week | |

| < 25 (n = 61) | 8.45 ± 2.21 | 1.03 ± 1.36 | 14.67 ± 6.15 | 9.40 ± 3.95 | 3.24 ± 3.19 | 2.49 ± 2.93 |

| 25-29.9 (n = 60) | 8.51 ± 2.25 | 2.36 ± 1.40 | 15.20 ± 5.97 | 10.78 ± 4.29 | 5.65 ± 3.25 | 4.78 ± 2.93 |

| 30-34.9 (n = 65) | 7.96 ± 2.52 | 4.69 ± 2.78 | 17.50 ± 5.97 | 13.43 ± 5.40 | 10.32 ± 5.78 | 10.10 ± 5.78 |

| >35 (n = 17) | 6.70 ± 2.56 | 5.23 ± 3.09 | 19.52 ± 4.81 | 17.70 ± 5.25 | 15.76 ± 6.48 | 14.70 ± 6.69 |

| P-value | 0.29 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

Table 3.

Behavioral rating scale in different weeks of study in four groups of body mass index

| BMI | BRS6 base | BRS6 after 4 week | BRS6 after 6 week | BRS6 after 8 week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 (n = 61) | 3.31 ± 1.07 | 2.47 ± 1.01 | 1.29 ± 0.97 | 0.44 ± 0.71 |

| 25-29.9 (n = 60) | 3.20 ± 1.05 | 2.43 ± 0.98 | 1.53 ± 0.85 | 1.06 ± 0.73 |

| 30-34.9 (n = 65) | 3.61 ± 1.01 | 3.01 ± 1.02 | 2.26 ± 0.90 | 2.15 ± 0.98 |

| >35 (n = 17) | 4.00 ± 0.79 | 3.58 ± 0.87 | 3.29 ± 0.84 | 3.23 ± 0.83 |

| P-value | 0.012 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

Figure 1.

Variations of visual analogue scale in different body mass index groups during the weeks of intervention

Figure 2.

Behavioral rating scale (BRS) in different body mass index groups during eight weeks of intervention

Table 2.

Visual analogue scale variations in different groups in different weeks of study

| BMI | 1st Week (mm) | 4th Week (mm) | 6th Week (mm) | 8th Week (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 (n = 61) | 71.04 ± 15.81 | 49.32 ± 13.91 | 23.49 ± 13.13 | 11.32 ± 12.58 |

| 25-29.9 (n = 60) | 70.33 ± 15.96 | 51.78 ± 15.00 | 33.88 ± 14.11 | 24.76 ± 12.89 |

| 30-34.9 (n = 65) | 76.00 ± 13.84 | 63.69 ± 13.61 | 54.00 ± 15.41 | 50.47 ± 16.36 |

| >35 (n = 17) | 82.64 ± 11.19 | 75.00 ± 12.74 | 71.47 ± 13.89 | 70.52 ± 14.37 |

| P-value | 0.007 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation

Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of BMI on the treatment of migraine headaches. As mentioned earlier, all patients were classified in four groups according to their BMI, and all were treated with the similar dosage of drugs. Age, height and weight were different in all four groups and increased with different BMI in different groups.

The mean frequency of pain was similar in all groups at the beginning but there was significant difference at the end of study. The mean duration of pain had significant difference in all groups at the beginning and at the end of 8th week. Mean VAS score did not show statistically significant difference between BMI groups at the beginning. However, the difference was statistically significant at the end of the study in favor of better response to treatment in lower BMI. BRS-6 score showed similar pattern.

In spite of direct influence of BMI on pain duration, it had no influence on pain frequency. However, comparing the influence of treatment on BMI in different groups showed that both frequency and duration had better outcome in patients with lower BMI. The findings of this study were in agreement with studies by Bigal et al.36 and Lipton et al.14 because their studies showed association between BMI and migraine headache, although these studies had different methods.

The findings of this study did not support Mattsson37 and Tietjen et al.38 which did not find direct influence of BMI on migraine headaches. The mechanism by which obesity affects on migraine or its treatment is unknown but mechanism that influence on body weight may simultaneously influence on migraine. Lower activity of sympathetic and higher activity of parasympathetic systems and secretion of special neuropeptides such as neuropeptide Y or melanocortins might be common factors.

Conclusion

This study showed that obesity has a direct influence on the treatment of migraine headaches. Treatment of migraine had direct association with BMI increments. Consequently, it should be recommended to patients to reduce their weight for better response to the treatment. In addition, physicians must be careful about migraine drugs which make a tendency for increased appetite.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Migraine at all ages. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10:207–13. doi: 10.1007/s11916-006-0047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elrington G. Migraine: diagnosis and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:ii10–ii5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.suppl_2.ii10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodick DW, Silberstein SD. Migraine prevention. Pract Neurol. 2007;7:383–93. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.134023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raskin NH. Headache. In: Kasper Dl, Fauci AS, Longo DL., editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 16th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silberstein SD. Migraine. Lancet. 2004;363:381–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horev A, Wirguin I, Lantsberg L, et al. A high incidence of migraine with aura among morbidly obese women. Headache. 2005;45:936–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Steiner TJ, et al. Classification of primary headaches. Neurology. 2004;63:427–35. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000133301.66364.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pakalnis A, Gladstein J. Headaches and hormones. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2010;17:100–4. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rapoport AM, Bigal ME. The clinical spectrum of migraine. Compr Ther. 2003;29:35–42. doi: 10.1007/s12019-003-0005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russell MB. Genetics in primary headaches. J Headache Pain. 2007;8:190–5. doi: 10.1007/s10194-007-0389-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandez F, Colson NJ, Griffiths LR. Pharmacogenetics of migraine: genetic variants and their potential role in migraine therapy. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:609–22. doi: 10.2217/14622416.8.6.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teepker M, Peters M, Kundermann B, et al. The effects of oral contraceptives on detection and pain thresholds as well as headache intensity during menstrual cycle in migraine. Headache. 2011;51:92–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuda K. Role of estrogen and endothelium in migraine in young women. Stroke. 2009;40:e705. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.566489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, von Korff M. Burden of migraine: societal costs and therapeutic opportunities. Neurology. 1997;48:4–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3_suppl_3.4s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipton RB, Scher AI, Kolodner K, et al. Migraine in the United States: epidemiology and patterns of health care use. Neurology. 2002;58:885–94. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.6.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogawski MA. Common Pathophysiologic Mechanisms in Migraine and Epilepsy. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:709–14. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.6.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.T-RKR U, KOER A, L-LECI A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of migraine in women of reproductive age in Istanbul, Turkey: A population based survey. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;206:51–9. doi: 10.1620/tjem.206.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartleson JD, Cutrer FM. Migraine update. Diagnosis and treatment. Minn Med. 2010;93:36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Overview on the prevalence and impact of migraine. J Headache Pain. 2004;5:88–91. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabricius M, Fuhr S, Bhatia R, et al. Cortical spreading depression and peri-infarct depolarization in acutely injured human cerebral cortex. Brain. 2006;129:778–90. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holroyd KA, Cottrell CK, O'Donnell FJ, et al. Effect of preventive (beta blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;29:341. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwasaki Y, Ikeda K. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology. 2007;68:241. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000255584.86414.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szyszkowicz M, Kaplan GG, Grafstein E, et al. Emergency department visits for migraine and headache: a multi-city study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2009;22:235–42. doi: 10.2478/v10001-009-0024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maggioni F, Ruffatti S, Dainese F, et al. Weight variations in the prophylactic therapy of primary headaches: 6-month follow-up. J Headache Pain. 2005;6:322–4. doi: 10.1007/s10194-005-0221-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bond DS, Roth J, Nash JM, et al. Migraine and obesity: epidemiology, possible mechanisms and the potential role of weight loss treatment. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e362–e371. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterlin BL, Rapoport AM, Kurth T. Migraine and obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and implications. Headache. 2010;50:631–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray ST, Kumar R. Migraine and obesity: cause or effect? Headache. 2010;50:326–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullally WJ, Hall K, Goldstein R. Efficacy of biofeedback in the treatment of migraine and tension type headaches. Pain Physician. 2009;12:1005–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinberg J. Anticonvulsant medications for migraine prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1699–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vikelis M, Rapoport AM. Role of antiepileptic drugs as preventive agents for migraine. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:21–33. doi: 10.2165/11310970-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoppe A, Weidenhammer W, Wagenpfeil S, et al. Correlations of headache diary parameters, quality of life and disability scales. Headache. 2009;49:868–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffmann W, Herzog B, Muhlig S, et al. Pharmaceutical care for migraine and headache patients: a community-based, randomized intervention. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:1804–13. doi: 10.1345/aph.1K635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silberstein SD, Dodick D, Freitag F, Pearlman SH, Hahn SR, Scher AI, et al. Pharmacological approaches to managing migraine and associated comorbidities--clinical considerations for monotherapy versus polytherapy. Headache. 2007;47:585–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents. Neurology. 2004;63:2215–24. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147332.41993.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bigal ME, Tsang A, Loder E, et al. Body mass index and episodic headaches: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1964–70. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.18.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mattsson P. Migraine headache and obesity in women aged 40-74 years: a population-based study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:877–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tietjen GE, Peterlin BL, Brandes JL, et al. Depression and anxiety: effect on the migraine-obesity relationship. Headache. 2007;47:866–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]