Background: Mammalian αE-catenin is an allosterically regulated F-actin binding protein that inhibits the Arp2/3 complex.

Results: D. rerio αE-catenin is a monomer that binds β-catenin and F-actin simultaneously but does not inhibit the Arp2/3 complex.

Conclusion: D. rerio αE-catenin directly links the cadherin-catenin complex to F-actin.

Significance: Core functions but not regulatory properties are conserved between α-catenin orthologs.

Keywords: Actin, Adherens Junction, Catenin, Cell Adhesion, Protein Evolution

Abstract

It is unknown whether homologs of the cadherin·catenin complex have conserved structures and functions across the Metazoa. Mammalian αE-catenin is an allosterically regulated actin-binding protein that binds the cadherin·β-catenin complex as a monomer and whose dimerization potentiates F-actin association. We tested whether these functional properties are conserved in another vertebrate, the zebrafish Danio rerio. Here we show, despite 90% sequence identity, that Danio rerio and Mus musculus αE-catenin have striking functional differences. We demonstrate that D. rerio αE-catenin is monomeric by size exclusion chromatography, native PAGE, and small angle x-ray scattering. D. rerio αE-catenin binds F-actin in cosedimentation assays as a monomer and as an α/β-catenin heterodimer complex. D. rerio αE-catenin also bundles F-actin, as shown by negative stained transmission electron microscopy, and does not inhibit Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation in bulk polymerization assays. Thus, core properties of α-catenin function, F-actin and β-catenin binding, are conserved between mouse and zebrafish. We speculate that unique regulatory properties have evolved to match specific developmental requirements.

Introduction

The cadherin-catenin complex mediates cell-cell adhesion (1) and is essential for normal development and tissue organization in the Metazoa (2). αE-catenin, a central component of the cadherin-catenin complex, is conserved throughout the Metazoa. In mammals, αE-catenin functionally links the cadherin·β-catenin complex to the actin cytoskeleton and regulates cell-cell adhesion and cell migration (2–8). This link is dynamic or regulated because mammalian αE-catenin binds the cadherin·β-catenin complex as a monomer and F-actin as a homodimer in bulk assays (9–13). Mammalian αE-catenin also stabilizes cell-cell contacts and inhibits cell migration by organizing F-actin (9) and inhibiting Arp2/3 complex-mediated nucleation of F-actin (12, 14).

Although the functions of mammalian αE-catenin are well defined, it is unknown whether its structural and biochemical properties are conserved in other organisms (15, 16). Previous studies examined whether the biochemical properties of mammalian αE-catenin are conserved in orthologs from Caenorhabditis elegans (17, 18) and Dictyostelium discoideum (19). The amino acid sequence identities of C. elegans HMP-1 (α-catenin) and D. discoideum α-catenin with M. musculus αE-catenin are low, 37 and 14%, respectively, and regulatory properties are not well conserved (12, 17–19): C. elegans HMP-1 is an autoinhibited monomer that binds weakly to F-actin in solution (17, 18), and D. discoideum α-catenin is a monomer that constitutively binds and bundles F-actin but does not inhibit Arp2/3-mediated actin nucleation (19). It is perhaps not surprising that these distantly related orthologs of α-catenin exhibit different organizational and functional properties. Therefore, we examined a closely related ortholog in the zebrafish, D. rerio, which is 90% identical in amino acid sequence to M. musculus αE-catenin. Despite the considerable sequence identity, there are remarkable differences in the functional properties of D. rerio αE-catenin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification

DNA encoding full-length (amino acids 1–907) D. rerio αE-catenin was inserted into an Smt3 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae SUMO) adapted pET28 (20) vector to generate an in-frame fusion between D. rerio αE-catenin and N-terminal His6-Smt3 tag. Recombinant fusion protein was expressed in BL21(DE3) Codon Plus E. coli cells (11), purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads, and eluted with imidazole. Protein was applied to a MonoQ anion exchange column and eluted at 200 mm NaCl in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mm DTT with a 0–1 m NaCl gradient. The His-Smt3 tag was removed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with Smt3 protease (Ulp1) at a 1:1000 Ulp1:D. rerio αE-catenin mass ratio. D. rerio αE-catenin was further purified by Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol and 1 mm DTT. Pure protein, eluted as a monomer at a concentration of 40–50 μm, was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. His6-TEV-D. rerio β-catenin (21) was expressed in BL21(DE3) Codon Plus E. coli cells, purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads, and cleaved off the beads by overnight incubation with TEV protease at 4 °C (where TEV is nuclear inclusion a (NIa) protease encoded by the tobacco etch virus). D. rerio β-catenin was purified on a MonoQ anion exchange column followed by a Superdex 200 gel filtration column in the same conditions as described for D. rerio αE-catenin. Recombinant full-length M. musculus αE-catenin (1–906) and M. musculus β-catenin (1–781) were expressed and purified as reported previously (13).

Size Exclusion Chromatography

Analytical size exclusion chromatography was performed at 4 °C using a Superdex 200 column in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mm DTT. Protein was injected at 20–30 μm.

Native PAGE

FPLC-purified D. rerio and M. musculus αE-catenin were diluted in ice-cold native gel sample buffer containing 20 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 150 mm NaCl, 300 mm sucrose, 100 mm DTT, and 0.02% bromphenol blue and loaded onto a 5% native gel (running gel (0.4 m Tris, pH 8.8, 5% acrylamide); stacking gel (0.1 m Tris, pH 6.8, 5% acrylamide)). Gels were run at 80 V for 5 h at 4 °C, stained with Coomassie Blue, and imaged on a LI-COR scanner.

Small Angle X-ray Scattering

Small angle scattering data were measured at beamline 4-2 at the Stanford Synchroton Radiation Laboratory. D. rerio αE-catenin was prepared in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, and 1% glycerol. Samples at concentrations of 5, 10, 20, and 30 μm were loaded into a 1.5-mm quartz capillary flow cell maintained at 20 °C, and 10 × 5-s exposures were measured from each concentration. The raw scattering data were normalized to the incident beam intensity, and buffer scattering was subtracted. The radius of gyration (Rg)3 was computed using the program Primus (22). Data used for estimating Rg were restricted to scattering angles for which the product q × (estimated Rg) ≤ 1.3 (q = 4πsin(θ)/λ). The molecular mass of D. rerio αE-catenin in solution was obtained from I(0) by extrapolation to q = 0 using water as the calibration standard and assuming a protein partial specific volume of 0.7586 cm3/g (23).

Limited Proteolysis and Edman Sequencing

12 μm D. rerio αE-catenin and 12 μm M. musculus αE-catenin were incubated at room temperature in 0.05 mg/ml sequence-grade trypsin (Roche Applied Science) in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT. Reactions were stopped with 2× Laemmli buffer at the indicated times, and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. For N-terminal sequencing, digested peptides were blotted onto PVDF membrane, stained with 0.1% Coomassie (R-250/40%methanol/1% acetic acid), destained, and dried. Individual bands were excised and sequenced by Edman degradation.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

ITC experiments were performed on a VP-ITC calorimeter (Microcal, GE Healthcare). For D. rerio αE-catenin/D. rerio β-catenin binding, a total of 31 9-μl aliquots of 100 μm D. rerio αE-catenin were injected into the cell, which contained 10 μm D. rerio β-catenin in 20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT at 25 °C. For D. rerio αE-catenin/M. musculus β-catenin binding, a total of 31 9-μl aliquots of 100 μm M. musculus β-catenin were injected into the cell, which contained 10 μm D. rerio αE-catenin in 20 mm Hepes, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT at 25 °C. Heat change was measured for 240 s between injections. For each experiment, the average value calculated from heat changes measured at saturation was subtracted from all data points.

Actin Cosedimentation Assays

Chicken muscle G-actin was incubated in 1× actin polymerization buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm ATP, and 1 mm EGTA) for 1 h at room temperature to polymerize filaments. Gel filtered D. rerio αE-catenin or D. rerio αE-catenin and D. rerio·M. musculus β-catenin heterocomplex was diluted to indicated concentrations in 1× reaction buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm ATP, 1 mm EGTA, and 1 mm DTT) with and without 2 μm F-actin and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were centrifuged at 100,000 rpm for 20 min in a TLA 120.1 rotor. Pellets were resuspended in 1× Laemmli sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie Blue. Gels were imaged on a LI-COR scanner and measured and quantified in ImageJ software. Binding data were processed with Prism software.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Protein samples were prepared as for actin cosedimentation assays and deposited on carbon grids. Samples were stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 3 min and examined in a JEOL TEM1230 electron microscope at 12,000× magnification. Brightness and contrast were adjusted in ImageJ software. No other manipulations were performed.

Actin Polymerization Assays

10% pyrene-labeled rabbit muscle G-actin (Cytoskeleton, Inc.) was diluted into fresh G buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 0.2 mm CaCl2, 0.2 mm ATP, and 1 mm DTT) immediately before use. 10% Pyrene-labeled G-actin was centrifuged for 30 min at 14,000 rpm in FA 45–30-11 rotor (Eppendorf) to remove aggregates. Prior to each experiment, Ca2+ was exchanged for Mg2+ by adding volume of 10 mm EGTA and 1 mm MgCl2 and incubating 2 min at room temperature. 10× Polymerization buffer was then added to a final concentration of 1× (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 100 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm ATP, and 1 mm EGTA) to initiate polymerization. Pyrene fluorescence (365 nm excitation, 407 nm emission) was measured every 10 s until the fluorescence reached a stable value (1000 s). Measurements were taken using a Tecan Infinite M1000 plate reader. The delay between addition of polymerization buffer and commencement of measurements was 10–20 s for all experiments. Where appropriate, bovine Arp2/3 complex and human GST-WASp-VCA were added to the reactions with polymerization buffer to a final concentration of 50 nm each. Full-length D. rerio αE-catenin, M. musculus αE-catenin, or rabbit α-actinin were gel filtered into 1× polymerization buffer prior to the experiment and added along with the polymerization buffer to a final concentration of 1–8 μm.

RESULTS

Domain Organization Is Conserved in D. rerio and M. musculus αE-catenin

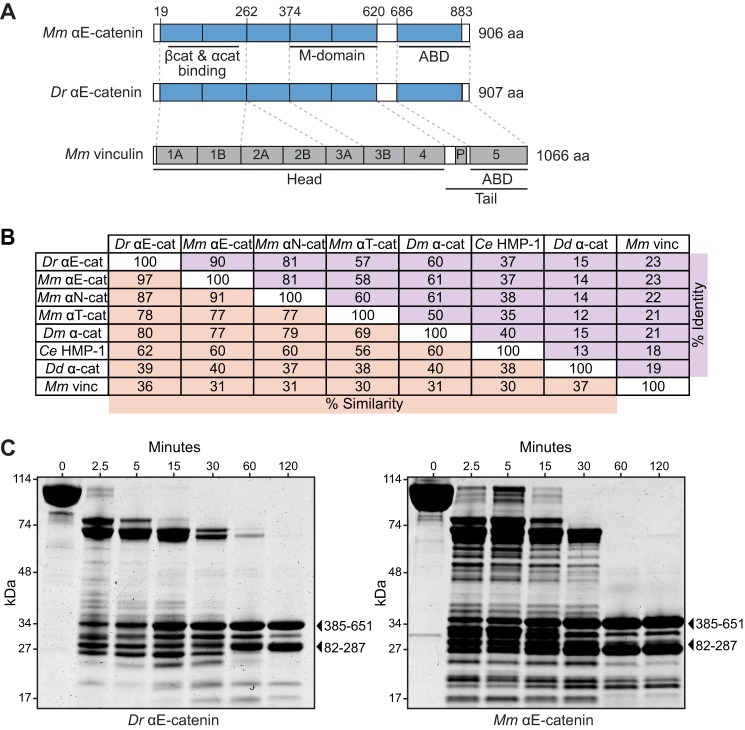

We compared the amino acid sequences of D. rerio αE-catenin, M. musculus αE-, αN-, and αT-catenins, Drosophila melanogaster α-catenin, C. elegans HMP-1, D. discoideum α-catenin and M. musculus vinculin. D. rerio αE-catenin is similar to M. musculus αE-catenin, but not M. musculus vinculin, in domain organization (Fig. 1A) and amino acid sequence (Fig. 1B). D. rerio αE-catenin is 90% identical to M. musculus αE-catenin but only 81 and 57% identical to M. musculus αN- and αT-catenin, respectively (Fig. 1B). Sequence identity between D. rerio αE-catenin and orthologs in lower organisms decreases to 60% (D. melanogaster α-catenin), 37% (C. elegans HMP-1), and 15% (D. discoideum α-catenin) (Fig. 1B). Thus, D. rerio αE-catenin is a member of the α-catenin family and is closely related to M. musculus αE-catenin.

FIGURE 1.

Domain organization is conserved in D. rerio and M. musculus αE-catenin. A, M. musculus vinculin (vinc) is composed of 7 four-helix bundles, a proline-rich hinge region, and a C-terminal five-helix bundle. α-catenins share a similar structure but lack the D2 domain. Head, tail, and actin-binding domains of vinculin as well as β-catenin (βcat) binding/dimerization, modulation, and F-actin binding domains in M. musculus αE-catenin are annotated. Regions of homology are indicated in D. rerio αE-catenin and by dashed lines. B, percent identity (purple) and percent similarity (orange) between D. rerio αE-catenin, M. musculus α-catenins (αE-, αN-, and αT-catenin), D. melanogaster α-catenin (αcat), C. elegans HMP-1, D. discoideum α-catenin, and M. musculus vinculin. C, limited proteolysis of D. rerio αE-catenin and M. musculus αE-catenin. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of proteins incubated for 0, 2.5, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min with 0.05 mg/ml trypsin. M-domain (residues 385–651) and dimerization domain (residues 82–287), as identified by Edman degradation N-terminal sequencing, are marked with arrows. M. musculus αE-catenin Edman sequencing results were published previously (17). aa, amino acids.

To determine whether the domain organization of D. rerio αE-catenin in solution is similar to M. musculus αE-catenin, we performed limited trypsin proteolysis (11). After 120 min of digestion, two stable fragments of D. rerio αE-catenin were detected by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C). N-terminal sequencing of these two fragments revealed they started at residues 82 and 385 respectively, which correspond to the proteolytically resistant domains identified previously in M. musculus αE-catenin (11, 24), the dimerization/β-catenin-binding domain (residues 82–287) and the M-domain (residues 385–651) (Fig. 1C). Despite conservation of potential cleavage sites in the sequences, a protease-resistant dimerization/β-catenin-binding domain is not observed in C. elegans HMP-1 (17) or D. discoideum α-catenin (19). This suggests reduced proteolytic sensitivity of N-terminal domains in vertebrate αE-catenins. A protected fragment of the actin-binding domain was not identified in either D. rerio αE-catenin or M. musculus αE-catenin. These results, taken together with sequence analysis, demonstrate that D. rerio αE-catenin is closely related to M. musculus αE-catenin.

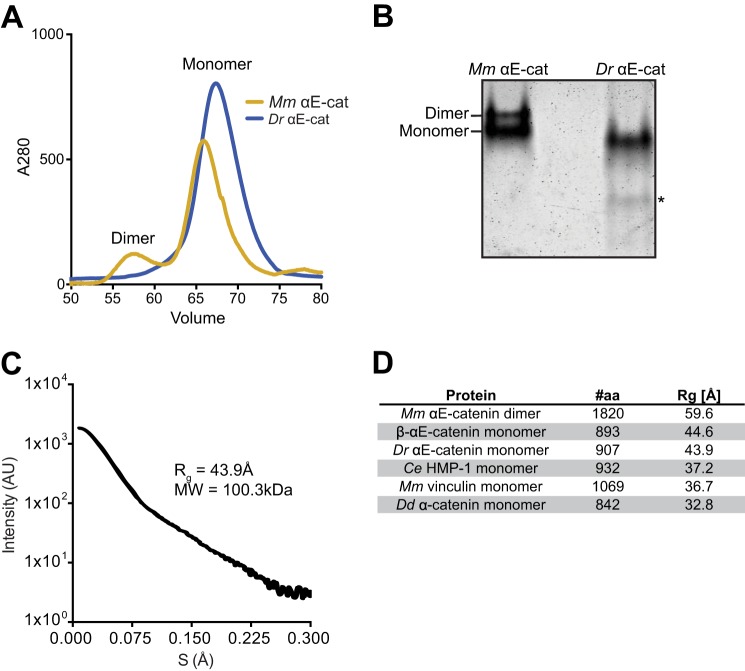

D. rerio αE-catenin Is a Monomer

We examined the oligomerization state of recombinant full-length D. rerio αE-catenin by size exclusion chromatography using Superdex 200, native PAGE, and small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) (17, 19). D. rerio αE-catenin eluted as a discrete peak with an estimated molecular weight of 100 kDa by size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2A), and migrated as a single band on native PAGE (Fig. 2B). SAXS curves were measured for D. rerio αE-catenin at a range of concentrations from 5–30 μm in solution (Fig. 2C). The predicted molecular mass of D. rerio αE-catenin monomer by sequence analysis is 100.5 kDa. The molecular mass for D. rerio αE-catenin obtained from the SAXS data is 100.3 ± 1.5 kDa, strongly supporting the conclusion that D. rerio αE-catenin is a monomer even at high concentrations. Furthermore, SAXS analysis yielded a radius of gyration (Rg) for D. rerio αE-catenin of 43.9 Å (Fig. 2C), which is similar to that of the M. musculus β-αE-catenin chimera monomer (Rg = 44.6 Å; Fig. 2D; 17). The β-αE-catenin chimera is a β-catenin-stabilized M. musculus αE-catenin monomer used because the contaminating presence of M. musculus αE-catenin dimer (Rg = 59.6 Å; 17) in preparations of M. musculus αE-catenin monomer (11) prevents accurate SAXS measurements. The Rg values indicate that D. rerio αE-catenin has an overall conformation similar to monomeric M. musculus αE-catenin but is less compact than the auto-inhibited monomeric proteins C. elegans HMP-1 and M. musculus vinculin (Rg = 37.2 and 36.7 Å, respectively; Fig. 2D) (17, 25). Unlike mammalian αE-catenin, but similar to C. elegans HMP-1 (17) and D. discoideum α-catenin (Rg = 32.8 Å; Fig. 2D) (19), D. rerio αE-catenin is a monomer in solution, at least to the highest measured concentration of 30 μm, well above the estimated cytosolic concentration of αE-catenin in mammalian epithelial cells (0.6 μm) (12).

FIGURE 2.

D. rerio αE-catenin is a monomer. A, Superdex 200 size exclusion chromatography of recombinant D. rerio αE-catenin (Dr αE-cat) and M. musculus αE-catenin (Mm αE-catenin). B, native PAGE of D. rerio αE-catenin and M. musculus αE-catenin. Monomer and dimer species of M. musculus αE-catenin are labeled. Asterisk in D. rerio αE-catenin lane marks a degradation product. C, SAXS analysis of D. rerio αE-catenin. Plot depicts raw data generated by merging scattering curves from 5, 10, 20, and 30 μm D. rerio αE-catenin. Estimated molecular weight and Rg of D. rerio αE-catenin in solution are shown. AU, arbitrary units. D, comparison of the Rg value obtained for D. rerio αE-catenin from SAXS analysis with the values previously reported for metazoan vinculin and α-catenins (17) and D. discoideum α-catenin (19).

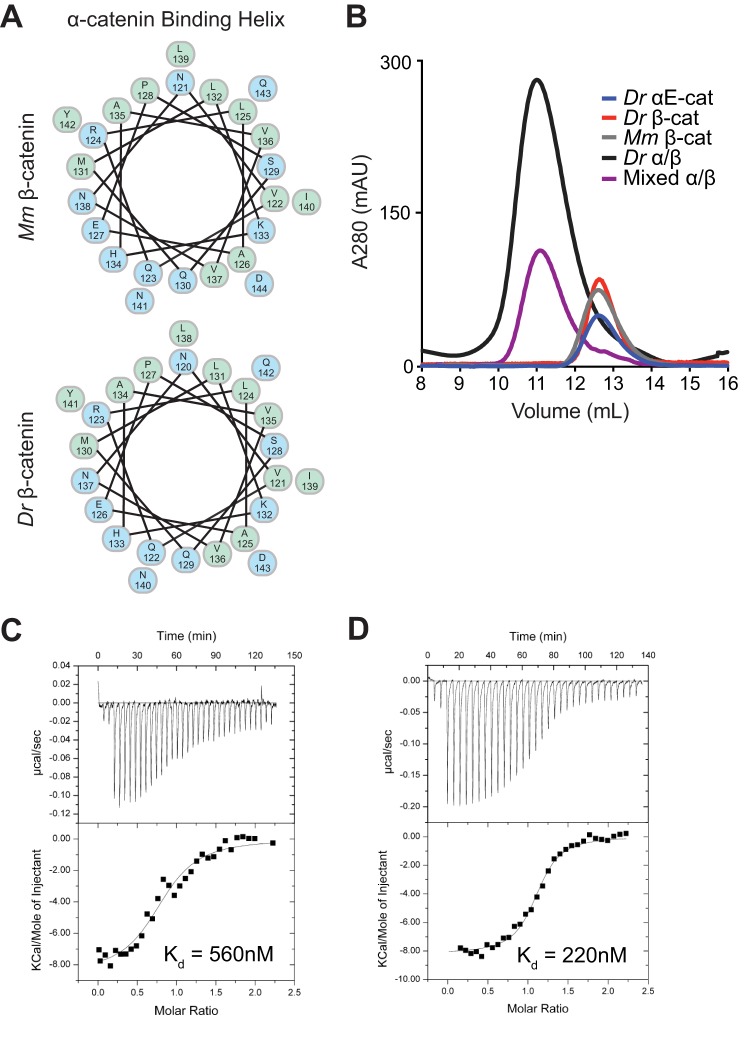

D. rerio αE-catenin Binds β-Catenin

We tested whether D. rerio αE-catenin binds to β-catenin in solution. We assayed binding to both D. rerio and M. musculus β-catenin because M. musculus β-catenin is 97% identical in overall sequence to D. rerio β-catenin, and the binding interfaces are 100% identical (Fig. 3A) (11). D. rerio αE-catenin was incubated in a 1:1 molar ratio with D. rerio or M. musculus β-catenin and then analyzed by Superdex 200 size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 3B). Although D. rerio αE-catenin, D. rerio β-catenin, and M. musculus β-catenin alone exhibited similar elution profiles, D. rerio αE-catenin incubated together with D. rerio β-catenin or M. musculus β-catenin eluted in earlier fractions (Fig. 3B), indicating formation of an α-catenin·β-catenin heterodimer complex. We then used isothermal titration calorimetry (26) to quantify the affinity of D. rerio αE-catenin for D. rerio β-catenin (Fig. 3C). The Kd value of D. rerio αE-catenin for D. rerio β-catenin, 560 nm, is an order of magnitude higher than the Kd of M. musculus αE-catenin for M. musculus β-catenin (23 nm).4 D. rerio αE-catenin also bound M. musculus β-catenin with a Kd of 220 nm by ITC (Fig. 3D). It is therefore likely that reduced affinity for β-catenin is an intrinsic property of D. rerio αE-catenin.

FIGURE 3.

D. rerio αE-catenin binds β-catenin. A, helical wheel representations of the identical α-catenin binding sites on M. musculus β-catenin (781 amino acids) and D. rerio β-catenin (780 amino acids). Polar residues are colored blue, and hydrophobic residues are colored green. B, Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography of D. rerio αE-catenin (αE-cat) and D. rerio β-catenin incubated in a 1:1 molar ratio (D. rerio heterodimer; black), D. rerio αE-catenin and M. musculus β-catenin incubated in a 1:1 molar ratio (mixed heterodimer; purple), D. rerio αE-catenin (blue), D. rerio β-catenin (red), and M. musculus β-catenin (gray). mAU, milli-absorbance unit. C, D. rerio αE-catenin binding to D. rerio β-catenin was quantified using ITC. 330 μl of 100 μm D. rerio αE-catenin was titrated into 2 ml of 10 μm D. rerio β-catenin by a series of 9-μl injections with a 240-s delay between each injection. The ratio of heat released (kcal) per mole of D. rerio αE-catenin injected into D. rerio β-catenin was plotted against the molar ratio of D. rerio αE-catenin and D. rerio β-catenin. The Kd obtained from these measurements is listed. D, D. rerio αE-catenin binding to M. musculus β-catenin was quantified using ITC. 330 μl of 100 μm M. musculus β-catenin was titrated into 2 ml of 10 μm D. rerio αE-catenin as in C.

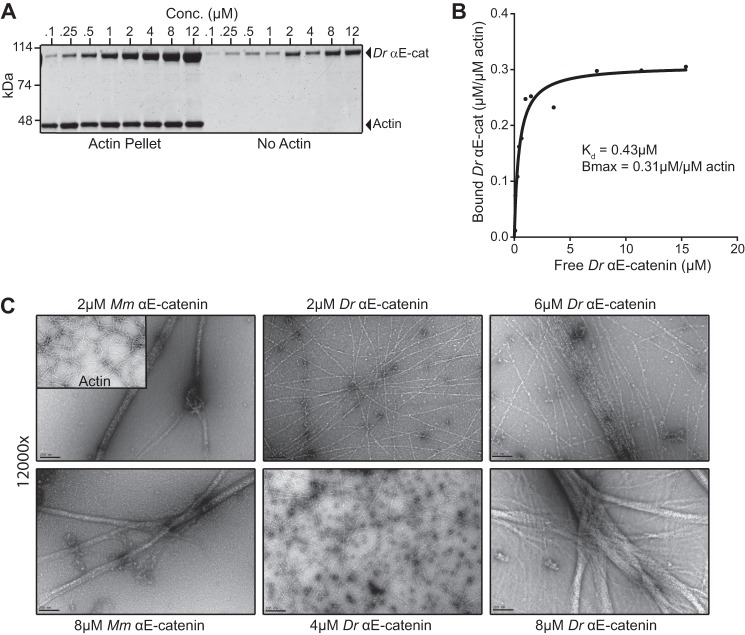

D. rerio αE-catenin Binds and Bundles F-actin

Mammalian αE-catenin binds and bundles actin filaments (Fig. 4) (9). We examined whether D. rerio αE-catenin binds to actin filaments (F-actin) using a high-speed cosedimentation assay (9, 11, 17, 19). D. rerio αE-catenin bound to F-actin with a Kd of 0.43 ± 0.3 μm (n = 3; Fig. 4, A and B), similar to mammalian αE-catenin and D. discoideum α-catenin (0.3 and 0.4 μm, respectively) (9).5 These data show that D. rerio αE-catenin is not autoinhibited in solution, compared with M. musculus vinculin and C. elegans HMP-1 (17, 25, 26), and that actin binding is a property conserved across the α-catenin family.

FIGURE 4.

D. rerio αE-catenin binds and bundles F-actin. A, high-speed cosedimentation assay of D. rerio αE-catenin (αE-cat) with F-actin. D. rerio αE-catenin was incubated with 2 μm F-actin at final concentrations (Conc.) of 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, and 12 μm. The actin pellet was the D. rerio αE-catenin bound to F-actin after centrifugation, and the no actin control was D. rerio αE-catenin that sedimented independently of F-actin. Samples were analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE. The example shown is representative of at least three independent experiments. B, bound D. rerio αE-catenin (μm/μm actin) was plotted against free D. rerio αE-catenin (μm) from a high-speed F-actin cosedimentation assay and fit to a hyperbolic function (black line; Kd and Bmax listed). C, negative-stain transmission electron micrographs of 2 μm F-actin in the presence of D. rerio αE-catenin or M. musculus αE-catenin at the indicated concentrations. The inset in the 2 μm D. rerio αE-catenin micrograph shows F-actin in the absence of α-catenin. All images are at 12,000× magnification.

To investigate whether D. rerio αE-catenin bundles F-actin, we used transmission electron microscopy to visualize negative stained F-actin incubated with D. rerio αE-catenin (Fig. 4C) (9, 19). D. rerio αE-catenin bundled 2 μm F-actin at 8 μm but not at lower concentrations. In contrast, M. musculus αE-catenin bundled 2 μm F-actin at 1–2 μm (Fig. 4C). Activation of a cryptic D. rerio αE-catenin dimerization domain upon actin binding or the presence of a second F-actin binding site with lower affinity on the N terminus could be responsible for F-actin weak bundling. Similar properties have been reported in α-catenin homologs: vinculin tail dimerizes only upon binding to F-actin (27), and the N-terminal domains of both D. discoideum α-catenin (19) and mammalian αE-catenin (9) have been shown to bind F-actin in vitro. Further work is required to determine the mechanism by which D. rerio αE-catenin interacts with actin filaments.

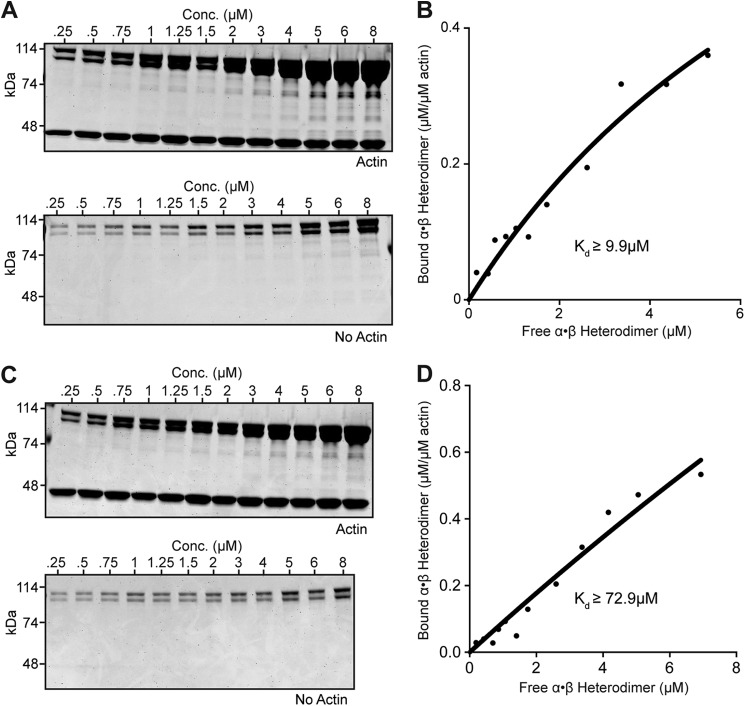

A Heterodimer of D. rerio αE-catenin and β-Catenin Binds F-actin

We performed high-speed cosedimentation assays of purified D. rerio α/β-catenin heterodimer with F-actin to investigate whether β-catenin regulates the binding of D. rerio αE-catenin to F-actin (9, 11). The D. rerio αE-catenin·D. rerio β-catenin heterodimer complex cosedimented with F-actin above background (Fig. 5A). At concentrations higher than 6–8 μm, the D. rerio αE-catenin·D. rerio β-catenin heterodimer sedimented independently of actin such that we were unable to saturate binding (Fig. 5B). Increasing the NaCl concentration in the reaction buffer to 300 mm and/or performing the experiment at 4 °C to limit aggregation did not reduce background sedimentation. Although saturation was not achieved, we can fit the curve with a single site-binding model to give a lower boundary on the Kd value (9.9 ± 4.5 μm; Fig. 5B). Thus, the D. rerio α·β-catenin heterodimer binds F-actin at least 10× more weakly than the D. rerio αE-catenin monomer (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the heterodimer of D. rerio αE-catenin and M. musculus β-catenin also cosedimented with F-actin above background but with at least an order of magnitude weaker affinity than the D. rerio αE-catenin monomer (Fig. 5, C and D).

FIGURE 5.

A heterodimer of D. rerio αE-catenin and β-catenin binds F-actin. A, high-speed cosedimentation assay of the D. rerio αE-catenin·D. rerio β-catenin heterodimer with F-actin. The D. rerio αE-catenin·D. rerio β-catenin heterodimer was incubated with 2 μm F-actin at the indicated concentrations (Conc.). The actin pellet was the heterodimer complex bound to F-actin after centrifugation, and the no-actin control was the heterodimer that sedimented independently of F-actin at the indicated concentrations. Samples were analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE. The example shown is representative of at least three independent experiments. B, bound D. rerio αE-catenin·D. rerio β-catenin heterodimer (μm/μm actin) was plotted against free heterodimer (μm) from A and fit to a hyperbolic function (black line; lower boundary of Kd is listed). C, high-speed cosedimentation assay of D. rerio αE-catenin·M. musculus β-catenin heterodimer with F-actin as in A. D, bound heterodimer (μm/μm actin) was plotted against free heterodimer (μm) and fit to a hyperbolic function (black line; lower boundary of Kd is listed).

Previous studies showed that binding to β-catenin weakens the affinity of mammalian αE-catenin for F-actin (12, 17, 28). Models of heterocomplex formation between mammalian αE-catenin and β-catenin suggest that β-catenin reduces access to the F-actin binding surface on the C-terminal actin binding domain of mammalian αE-catenin (21, 28). Therefore, the link between the cadherin·catenin complex at the adherens junction and the actomyosin cytoskeleton in cells is either dynamic/regulated (12–14, 17) or indirect through another actin binding protein that interacts with αE-catenin such as vinculin (29), α-actinin (30), afadin (24), EPLIN (31), or ZO-1 (32). The result that the D. rerio αE-catenin·β-catenin heterocomplex binds F-actin indicates that D. rerio αE-catenin may provide a direct link between the actin cytoskeleton and the cadherin·catenin complex in the adherens junction.

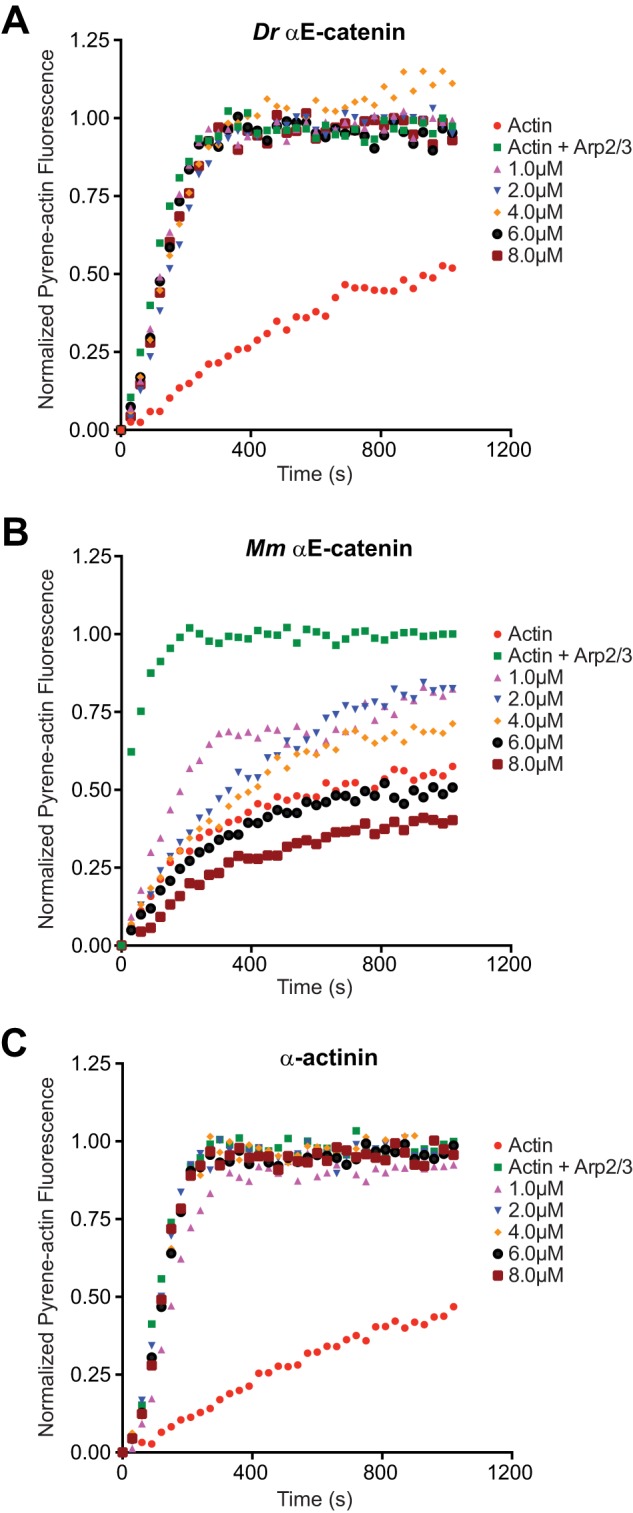

D. rerio αE-catenin Does Not Inhibit Arp2/3-mediated Nucleation of F-actin

In addition to binding and bundling F-actin, M. musculus αE-catenin regulates actin polymerization and cell migration through inhibition of the Arp2/3 complex (12, 14). Therefore, we tested whether D. rerio αE-catenin inhibits Arp2/3-complex-mediated actin nucleation using a standard pyrene-actin fluorescence assay (12, 19, 33). Addition of 1–8 μm D. rerio αE-catenin to 2 μm G-actin with 50 nm Arp2/3 and 50 nm WASp-VCA did not affect the rate of actin nucleation (Fig. 6A). In contrast, 1–8 μm M. musculus αE-catenin dimer inhibited Arp2/3 complex-mediated nucleation of F-actin in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). At concentrations of 6–8 μm, M. musculus αE-catenin suppressed F-actin polymerization below that of F-actin without Arp2/3 and WASp-VCA (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

D. rerio αE-catenin does not inhibit Arp2/3 complex-mediated nucleation of F-actin. A, effect of D. rerio αE-catenin on Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization in pyrene-actin assay. Reactions contained 2 μm actin with 10% pyrene-actin (red) plus 50 nm Arp2/3 complex and 50 nm WASp-VCA (green) and 1, 2, 4, 6, or 8 μm D. rerio α-catenin (indicated colors). The example shown is representative of at least three independent experiments. B and C, effect of M. musculus αE-catenin (B) and α-actinin (C) on Arp2/3-mediated actin polymerization.

Because M. musculus αE-catenin bundles F-actin at lower concentrations than D. rerio αE-catenin (Fig. 4C), it is possible that F-actin bundling sterically hinders nucleation by Arp2/3. To exclude this possibility, we performed the pyrene-actin fluorescence assay with the actin-bundling protein α-actinin (Fig. 6C) (12). 1–8 μm α-actinin did not inhibit the Arp2/3 complex-dependent increase in pyrene-actin fluorescence or polymerization kinetics (Fig. 6C), confirming results published previously (12).

DISCUSSION

Correlating Biochemical Properties of D. rerio αE-catenin and M. musculus αE-catenin with Loss of Function Phenotypes

The biochemical data presented here show that D. rerio αE-catenin binds to F-actin by itself or in the presence of β-catenin, unlike orthologs in M. musculus (12–13, 26) and C. elegans (17). Thus, D. rerio αE-catenin may provide a direct link between the cadherin·β-catenin complex and the actin cytoskeleton. However, this activity of D. rerio αE-catenin is regulated: the affinity of the αE-catenin·β-catenin complex for F-actin is at least an order of magnitude weaker than that of D. rerio αE-catenin alone. Also, unlike mammalian αE-catenin, D. rerio αE-catenin does not inhibit Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin nucleation.

Do these differences in biochemical properties of M. musculus αE-catenin and D. rerio αE-catenin reflect differences in loss-of-function phenotypes in the mouse and zebrafish, respectively? Loss of αE-catenin function in mammals (3–7) and zebrafish (34) leads to a decrease in cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. However, in mammals, loss of αE-catenin increases Arp2/3 complex-dependent lamellipodial dynamics (5, 14), whereas in zebrafish, D. rerio αE-catenin depletion increases membrane blebbing (34). Membrane blebbing is caused by localized loss of attachment of the plasma membrane to the cortical cytoskeleton, which allows hydrostatic pressure in the cytoplasm to induce membrane protrusions independent of the Arp2/3 complex (35). The ability of D. rerio αE-catenin to directly link β-catenin to F-actin in vitro suggests the cadherin·catenin complex may function as a membrane anchor for the cortical actomyosin cytoskeleton in zebrafish, as proposed for mammalian cells (36) and D. melanogaster (37).

Disruption of adhesion tension in gastrulation stage zebrafish embryos (38) supports the role of the zebrafish cadherin·catenin complex as a membrane anchor for the cortical actin cytoskeleton. Physical separation of ectodermal progenitor cells disrupts adhesion tension, causing distortions in plasma membrane curvature, such that D. rerio αE-catenin and F-actin no longer co-localize with β-catenin and E-cadherin at the plasma membrane (38). However, D. rerio αE-catenin and F-actin co-localize with one another in the cytoplasm (38). Despite clear differences in the biochemical activities of M. musculus and D. rerio αE-catenin, further work is required to understand the relationship between these in vitro activities with in vivo functional differences.

D. rerio αE-catenin and Protein Evolution Studies

We find functional differences between two vertebrate αE-catenins, mouse and zebrafish, that are 90% identical in sequence. Our results suggest that changes in a small number of amino acids have a critical role in the evolution of structure and function in αE-catenin. 26 of 907 residues are not similar in size and/or charge between D. rerio and M. musculus αE-catenin. We posit that adaptive changes in regions that regulate α-catenin conformation caused mammalian and zebrafish αE-catenins to develop distinct functional properties to match specific developmental requirements. However, further work is required to identify the specific residues that regulate function in vertebrate αE-catenin orthologs. Moreover, every α-catenin heretofore characterized has exhibited distinct biochemical properties (12, 17–19), and no cohesive model of α-catenin structure/function evolution exists. The evolutionary development of α-catenin as a direct link between β-catenin at the adherens junction and the actin cytoskeleton is unresolved. Although data presented here suggest D. rerio αE-catenin can act as a direct link, work with orthologs from mammals (12–13) and C. elegans (17) indicate that the linkage is indirect and/or tightly regulated. We propose that association of α-catenin with β-catenin is a conserved mechanism for negative regulation of actin binding. It remains to be determined whether homodimerization, strong F-actin bundling, and Arp2/3 inhibition are required properties of α-catenins in other metazoans or instead specific characteristics of mammalian αE-catenin. Examining orthologs from several other organisms and investigating directly the effects of amino acid changes will provide information to develop a model for αE-catenin structure/function evolution.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Weiss at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource for assistance with SAXS measurements, John Perrino at the Stanford University Cell Sciences Imaging Facility for help with TEM, Antonino Schepis for the D. rerio αE-catenin cDNA, and Wenqing Xu for the D. rerio β-catenin plasmid.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award GM007276 (to P. W. M.), National Institutes of Health Grant GM35527 (to W. J. N.), and National Institutes of Health Grant U01 GM94663 (to W. J. N., W. I. W., and S. A.).

S. Pokutta, unpublished data.

D. J. Dickinson, unpublished data.

- Rg

- radius of gyration

- SAXS

- small angle X-ray scattering

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- VCA

- verprolin, cofilin, acidic

- WASp

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nelson W. J. (2008) Regulation of cell-cell adhesion by the cadherin-catenin complex. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 149–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gumbiner B. M. (2005) Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 622–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larue L., Antos C., Butz S., Huber O., Delmas V., Dominis M., Kemler R. (1996) A role for cadherins in tissue formation. Development 122, 3185–3194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Torres M., Stoykova A., Huber O., Chowdhury K., Bonaldo P., Mansouri A., Butz S., Kemler R., Gruss P. (1997) An αE-catenin gene trap mutation defines its function in preimplantation development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 901–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vasioukhin V., Bauer C., Degenstein L., Wise B., Fuchs E. (2001) Hyperproliferation and defects in epithelial polarity upon conditional ablation of α-catenin in skin. Cell 104, 605–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watabe M., Nagafuchi A., Tsukita S., Takeichi M. (1994) Induction of polarized cell-cell association and retardation of growth by activation of the E-cadherin-catenin adhesion system in a dispersed carcinoma line. J. Cell Biol. 127, 247–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bullions L. C., Notterman D. A., Chung L. S., Levine A. J. (1997) Expression of wild-type α-catenin protein in cells with a mutant α-catenin gene restores both growth regulation and tumor suppressor activities. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 4501–4508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harris T. J., Tepass U. (2010) Adherens junctions: from molecules to morphogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 502–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rimm D. L., Koslov E. R., Kebriaei P., Cianci C. D., Morrow J. S. (1995) α 1(E)-catenin is an actin-binding and -bundling protein mediating the attachment of F-actin to the membrane adhesion complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8813–8817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koslov E. R., Maupin P., Pradhan D., Morrow J. S., Rimm D. L. (1997) α-catenin can form asymmetric homodimeric complexes and/or heterodimeric complexes with β-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 27301–27306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pokutta S., Weis W. I. (2000) Structure of the dimerization and β-catenin-binding region of α-catenin. Mol. Cell 5, 533–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drees F., Pokutta S., Yamada S., Nelson W. J., Weis W. I. (2005) α-catenin is a molecular switch that binds E-cadherin-β-catenin and regulates actin-filament assembly. Cell 123, 903–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yamada S., Pokutta S., Drees F., Weis W. I., Nelson W. J. (2005) Deconstructing the cadherin-catenin-actin complex. Cell 123, 889–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Benjamin J. M., Kwiatkowski A. V., Yang C., Korobova F., Pokutta S., Svitkina T., Weis W. I., Nelson W. J. (2010) αE-catenin regulates actin dynamics independently of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 189, 339–352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dickinson D. J., Weis W. I., Nelson W. J. (2011) Protein evolution in cell and tissue development: going beyond sequence and transcriptional analysis. Dev. Cell 21, 32–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dickinson D. J., Nelson W. J., Weis W. I. (2012) An epithelial tissue in Dictyostelium challenges the traditional origin of metazoan multicellularity. Bioessays 34, 833–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kwiatkowski A. V., Maiden S. L., Pokutta S., Choi H. J., Benjamin J. M., Lynch A. M., Nelson W. J., Weis W. I., Hardin J. (2010) In vitro and in vivo reconstitution of the cadherin-catenin-actin complex from Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14591–14596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maiden S. L., Harrison N., Keegan J., Cain B., Lynch A. M., Pettitt J., Hardin J. (2013) Specific conserved C-terminal amino acids of Caenorhabditis elegans HMP-1/α-catenin modulate F-actin binding independently of vinculin. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 5694–5706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dickinson D. J., Nelson W. J., Weis W. I. (2011) A polarized epithelium organized by β- and α-catenin predates cadherin and metazoan origins. Science 331, 1336–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mossessova E., Lima C. D. (2000) Ulp1-SUMO crystal structure and genetic analysis reveal conserved interactions and a regulatory element essential for cell growth in yeast. Mol. Cell 5, 865–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xing Y., Takemaru K., Liu J., Berndt J. D., Zheng J. J., Moon R. T., Xu W. (2008) Crystal structure of a full-length β-catenin. Structure 16, 478–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Konarev P. V., Volkov V. V., Sokolova A. V., Koch M. H. J., Svergun D. I., Koch H. J. (2003) PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 1277–1282 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Orthaber D., Bergmann A., Glatter O. (2000) SAXS experiments on absolute scale with Kratky systems using water as a secondary standard. J. Appl. Cryst. 33, 218–225 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pokutta S., Drees F., Takai Y., Nelson W. J., Weis W. I. (2002) Biochemical and structural definition of the l-afadin- and actin-binding sites of α-catenin. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18868–18874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ziegler W. H., Liddington R. C., Critchley D. R. (2006) The structure and regulation of vinculin. Tr. Cell Biol. 16, 453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi H. J., Pokutta S., Cadwell G. W., Bobkov A. A., Bankston L. A., Liddington R. C., Weis W. I. (2012) αE-catenin is an autoinhibited molecule that coactivates vinculin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8576–8581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Janssen M. E., Kim E., Liu H., Fujimoto L. M., Bobkov A., Volkmann N., Hanein D. (2006) Three-dimensional structure of vinculin bound to actin filaments. Mol. Cell 21, 271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rangarajan E. S., Izard T. (2013) Dimer asymmetry defines α-catenin interactions. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 188–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Watabe-Uchida M., Uchida N., Imamura Y., Nagafuchi A., Fujimoto K., Uemura T., Vermeulen S., van Roy F., Adamson E. D., Takeichi M. (1998) α-catenin-vinculin interaction functions to organize the apical junctional complex in epithelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 142, 847–857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Knudsen K. A., Soler A. P., Johnson K. R., Wheelock M. J. (1995) Interaction of α-actinin with the cadherin/catenin cell-cell adhesion complex via α-catenin. J. Cell Biol. 130, 67–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abe K., Takeichi M. (2008) EPLIN mediates linkage of the cadherin catenin complex to F-actin and stabilizes the circumferential belt. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 13–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Itoh M., Nagafuchi A., Moroi S., Tsukita S. (1997) Involvement of ZO-1 in cadherin-based cell adhesion through its direct binding to α catenin and actin filaments. J. Cell Biol. 138, 181–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mullins R. D., Machesky L. M. (2000) Actin assembly mediated by Arp2/3 complex and WASP family proteins. Methods Enzymol. 325, 214–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schepis A., Sepich D., Nelson W. J. (2012) αE-catenin regulates cell-cell adhesion and membrane blebbing during zebrafish epiboly. Development 139, 537–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Charras G., Paluch E. (2008) Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 730–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Borghi N., Sorokina M., Shcherbakova O. G., Weis W. I., Pruitt B. L., Nelson W. J. (2012) E-cadherin is under constitutive actomyosin-generated tension that is increased at cell-cell contacts upon externally applied stretch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12568–12573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Desai R., Sarpal R., Ishiyama N., Pellikka M., Ikura M., Tepass U. (2013) Monomeric α-catenin links cadherin to the actin cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 261–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maître J. L., Berthoumieux H., Krens S. F., Salbreux G., Jülicher F., Paluch E., Heisenberg C. P. (2012) Adhesion functions in cell sorting by mechanically coupling the cortices of adhering cells. Science 338, 253–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]