Background: Phosphorylation of Tyr-823 in the A-loop of c-Kit is not required for kinase activity but might have other functions.

Results: Mutation of Tyr-823 in c-Kit causes alterations in downstream signaling and a reduction in ligand-dependent cell survival and proliferation.

Conclusion: Phosphorylation of Tyr-823 regulates c-Kit stability.

Significance: This provides a function for the activation loop tyrosine of c-Kit.

Keywords: Cell Death, Cell Proliferation, Growth Factors, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, Ubiquitination, Cbl, Activation Loop, c-Kit

Abstract

The receptor tyrosine kinase c-Kit, also known as the stem cell factor receptor, plays a key role in several developmental processes. Activating mutations in c-Kit lead to alteration of these cellular processes and have been implicated in many human cancers such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors, acute myeloid leukemia, testicular seminomas and mastocytosis. Regulation of the catalytic activity of several kinases is known to be governed by phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the activation loop of the kinase domain. However, in the case of c-Kit phosphorylation of Tyr-823 has been demonstrated to be a late event that is not required for kinase activation. However, because phosphorylation of Tyr-823 is a ligand-activated event, we sought to investigate the functional consequences of Tyr-823 phosphorylation. By using a tyrosine-to-phenylalanine mutant of tyrosine 823, we investigated the impact of Tyr-823 on c-Kit signaling. We demonstrate here that Tyr-823 is crucial for cell survival and proliferation and that mutation of Tyr-823 to phenylalanine leads to decreased sustained phosphorylation and ubiquitination of c-Kit as compared with the wild-type receptor. Furthermore, the mutated receptor was, upon ligand-stimulation, quickly internalized and degraded. Phosphorylation of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl was transient, followed by a substantial reduction in phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules such as Akt, Erk, p38, Shc, and Gab2. Thus, we propose that activation loop tyrosine 823 is crucial for activation of both the MAPK and PI3K pathways and that its disruption leads to a destabilization of the c-Kit receptor and decreased survival of cells.

Introduction

c-Kit belongs to the family of type III receptor tyrosine kinases and is known for its critical role in hematopoiesis, pigmentation, and reproduction. It is also important for survival, proliferation, and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells (1, 2). Several activating mutations in c-Kit lead to a deregulation of the signaling cascades, causing malignancies such as acute myeloid leukemia, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and testicular seminomas (3–6). Architecturally, c-Kit is comprised of five extracellular immunoglobulin-like domains, a transmembrane domain, a juxtamembrane region, a kinase domain split into two parts by a kinase insert, and a carboxyterminal tail. The activation loop is present in the C-terminal lobe of the kinase domain. Activation of the receptor is initiated by binding of its ligand, stem cell factor (SCF)2, which leads to receptor dimerization and transphosphorylation on specific tyrosine residues. These phosphorylated residues serve as docking sites for signal transduction molecules containing SH2 (Src homology 2) domains such as Cbl, Gab2, Shc, and SHP2. They are activated upon phosphorylation and/or binding to the receptor and mediate signaling downstream of the receptor that eventually leads to various cellular responses. Many receptor tyrosine kinases undergo monoubiquitination or polyubiquitination following ligand stimulation, which targets them for degradation in the lysosomes or proteasomes, respectively. Members of Cbl family of ubiquitin E3 ligases play a crucial role in ubiquitination of c-Kit (1, 7, 8).

In many tyrosine kinases, phosphorylation of tyrosine residue(s) in the activation loop is a crucial early event that leads to activation of the kinase. Examples of this type of receptors include the insulin receptor and the FGFR1 (9, 10). However, in the case of c-Kit, the phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the juxtamembrane region is the most important activating event. In the absence of phosphorylation of the juxtamembrane region, it is inserted into a cleft between the N-terminal and C-terminal lobes of the kinase domain. Thereby, the so-called C-helix is disrupted, and the DFG motif is prevented from establishing an active conformation. Upon phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues in the juxtamembrane region, it is released together with the activation loop from the active site. The C-helix can move into position in the active site and, thereby, correctly orient the DFG residues that are important for catalytic activity (11, 12).

Kinetic studies on recombinant c-Kit in vitro using mass spectrometry revealed that phosphorylation of Tyr-823 is a late event that was observed when 90% of the kinase was already phosphorylated (13). Mutation of Tyr-823 to a phenylalanine residue did not impair kinase activity. Further, Mol et al. (11) showed that, in a crystal structure of inactivated enzyme, Tyr-823 is bound to the catalytic base Asp-792, blocking the access of substrates to the catalytic site. Therefore, phosphorylation of Tyr-823 may disengage the activation loop from its inhibitory state. Another possibility is that phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of Tyr-823 stabilizes the receptor structure and downstream signaling without being directly involved in kinase activity. However, the role of Tyr-823 and its effects on c-Kit signaling have not been studied until now.

In this study, we investigated the cellular and biochemical effects of mutating Tyr-823 to phenylalanine (Y823F). We show that Tyr-823 is crucial for cell survival and proliferation. Cells expressing the Y823F mutant of c-Kit showed much lower proliferation and survival as compared with cells expressing the wild-type receptor despite the fact that the kinase activity was intact. Furthermore, the Y823F mutant receptor was internalized and degraded much faster than the wild-type receptor. A reduction in phosphorylation of the adaptor proteins Cbl, Shc, and Gab2 was also seen. The PI3-kinase/Akt, Ras/Erk, and p38 pathways were also affected in that the phosphorylation of Akt, Erk, and p38 was very transient and not sustained as in wild-type c-Kit. Taken together, this study adds a novel perspective toward understanding the role of the activation loop tyrosine in c-Kit that is related to downstream signaling rather than kinase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

The transfection reagent Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen, and jetPEI was from Polyplus. Cycloheximide was purchased from Sigma. Human recombinant SCF and murine recombinant IL-3 were obtained from ProSpec Tany Technogene (Rehovot, Israel). Rabbit polyclonal anti-c-Kit serum was raised against a synthetic peptide corresponding to the carboxyterminus of c-Kit and purified as described (14). The anti-Cbl antibodies have been described elsewhere (15). The phospho-tyrosine antibody 4G10 was purchased from Millipore, and ubiquitin antibody was purchased from Covance Research Products. Antibodies against phospho-p38, p38, and Shc were from BD Transduction Laboratories. Phycoerythrin-labeled c-Kit antibody was from BD Biosciences. Anti-phospho-Akt antibody was from Epitomics. Polyclonal anti-Gab2, anti-Akt, anti-phospho-Erk, anti-Erk, and horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary anti-goat antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies were from Invitrogen.

Cell Culture

Ba/F3 cells and M07e cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 10 ng/ml recombinant murine IL-3 or 10 ng/ml recombinant human IL3, respectively. Kasumi-1 cells were cultivated in the above medium lacking IL-3. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 units/ml penicillin was used to culture COS-1 and EcoPack cells.

Expression Constructs

The pcDNA3-c-Kit-WT, and pMSCV-c-Kit-WT constructs were described previously (1, 8). The pcDNA3-c-Kit Y823F and pMSCV-c-Kit-Y823F constructs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange mutagenesis XL kit (Stratagene). All plasmids were verified by sequencing.

Transient and Stable Transfection

Transient transfection of COS1 cells was performed using the transfection reagent JetPEI according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Transfected cells were incubated for about 30 h before they were serum-starved overnight. Cell stimulation, lysis, and immunoprecipitation were performed essentially according to Ref. 16. Stable transfections were performed essentially as described (17). Cells expressing wild-type c-Kit or c-Kit Y823F were confirmed by flow cytometry.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

Cell lysis, immunoprecipitation, and Western blotting were performed as described (16). Immunodetection was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence using horseradish peroxidase substrate (Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA), and the signals were detected by a CCD (charge-coupled device) camera (LAS-3000, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). Signal intensities were further quantified by Multi-Gauge software (Fujifilm).

In Vitro Kinase Activity Assays

COS-1 cells transfected with the pCDNA3-cKit-WT and pCDNA3-c-Kit-Y823F plasmids were starved of serum overnight. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml SCF ligand, and cell lysates were prepared. The c-Kit receptor was immunoprecipitated and processed for in vitro kinase reaction essentially as described (18), except that 5 μg of myelin basic protein was used as exogenous kinase substrate. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for variable periods of time, and the reaction was stopped with 2× sample buffer. Samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto an Immobilon P membrane. Phosphorylation signals were detected using a phosphorimager (FLA-3000, Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). Equal loading was verified by Western blotting with a c-Kit antibody. To eliminate background phosphorylation on phosphoserine, alkali treatment of filters was performed essentially according to Ref. 19.

Cell Proliferation and Survival Assay

Ba/F3 cells were washed three times with RPMI 1640 medium and seeded in 24-well plates (70,000 cells/well). Cells were then incubated either with 100 ng/ml SCF without cytokine or with 10 ng/ml IL-3 for 48 h. Viable cells were counted using the trypan blue exclusion method. Alternatively, cells were stained with a Click-iT 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine Alexa 647 (Invitrogen) cell proliferation kit employing the protocol of the manufacturer. Stained cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur). Apoptosis was measured using an annexin V/7-amino-actinomycin D kit (BD Biosciences) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Double negative (annexin V)/(7-amino-actinomycin D) cells represent viable cells.

Internalization Experiment

For internalization assay, Ba/F3 cells were incubated with 100 μg/ml of cycloheximide and starved for 4 h at 37 °C in RPMI 1640 medium lacking serum and cytokines. Cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml SCF for the indicated periods of time. To assess internalization, cells were stained with a phycoerythrin-labeled anti-c-Kit antibody, and surface expression of the c-Kit receptor was determined by flow cytometry. Alternatively, receptor internalization was verified by Western blotting. A freshly prepared solution of 0.2 mg/ml EZ-Link sulfo-NHS-biotin (Thermo Scientific) dissolved in PBS was added to cells. The cells were then incubated on ice for 40 min to allow biotinylation of cell surface proteins. After incubation, excessive biotin was removed by washing once with cold PBS. In addition, 50 mm cold Tris was added to the cells to block excessive reactive biotin. After 5 min of blocking, cells were lysed and processed for pull-down with immobilized avidin-agarose (Thermo Scientific). The supernatant obtained after centrifugation was subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Kit antibody. c-Kit from both fractions was detected by Western blotting.

Degradation Experiments

Ba/F3 cells were incubated with 100 μg/ml of cycloheximide and starved, followed by stimulation with SCF for the indicated periods of time. For protein degradation experiments, ligand stimulation was followed by lysis and immunoprecipitation with a c-Kit antibody. Cell lysates obtained after stimulation were subjected to immunoprecipitation followed by detection of c-Kit by Western blotting using an antibody against c-Kit.

RESULTS

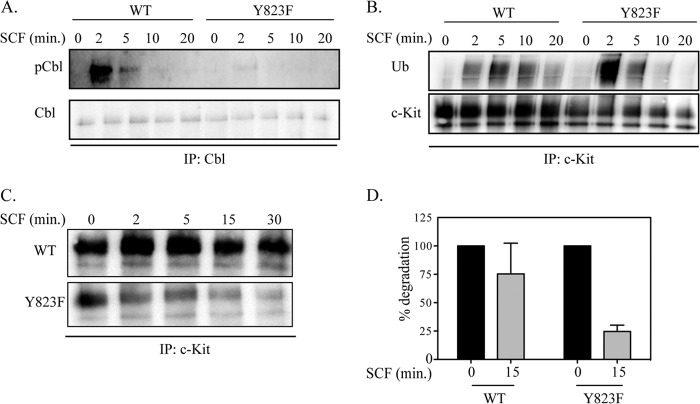

The Activation Loop Y823F Mutation Accelerates Receptor Phosphorylation

The kinase domain of c-Kit is known to interact with juxtamembrane (JM) domain to maintain the kinase in an inhibitory state. When four tyrosine residues of the JM domain (at positions 547, 553, 568, and 570) are phosphorylated upon ligand stimulation, The JM domain is released from the kinase domain, and the substrate can interact with the catalytic site. In addition, the activation loop transits from the DFG-out to the DFG-in state in transition from the inactivated state to the activated state. Together these two changes make the kinase catalytically active (13). We wanted to assess the changes in kinase activity of the receptor if the activation loop tyrosine, Tyr-823, was mutated. Therefore, we generated the Y823F mutant of c-Kit and stably transfected it into Ba/F3 cells. Ba/F3 is an immortalized murine bone marrow-derived pro-B cell line that is dependent on IL-3 for its growth (20). We have used Ba/F3 cells in this study because this cell line does not express c-Kit endogenously and, therefore, can be used to overexpress both the wild-type and mutant forms of human c-Kit. We also performed experiments with wild-type c-Kit and Y823F c-Kit by transient transfections in Cos1 cells. Both cells lines were tested for cell surface expression of c-Kit by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A). To verify that overexpression of c-Kit WT and c-Kit Y823F was comparable with endogenous expression of c-Kit, we used two leukemic cell lines, Mo7e and Kasumi, as controls (Fig. 1B). We further observed that both the wild-type c-Kit as well as Y823F c-Kit are phosphorylated rapidly after stimulation with SCF. However, the onset of phosphorylation in the mutant was faster and stronger than in wild-type c-Kit. It rapidly declined in the Y823F mutant, whereas wild-type c-Kit showed a more sustained response (Fig. 1C). This suggests that there is either a conformational change in the Y823F mutant or that the mutant c-Kit stability is altered.

FIGURE 1.

The Y823F mutation leads to enhanced and faster phosphorylation of the c-Kit receptor. A, stably transfected Ba/F3 cells were labeled with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-c-Kit antibodies or an isotype control and analyzed by flow cytometry. The black peak indicates cells labeled with the isotype control, and the gray peak corresponds to the cells labeled with anti-c-Kit antibody. B, the Mo7e and Kasumi cell lines expressing endogenous c-Kit and Ba/F3 cells expressing c-Kit and c-Kit/Y823F were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Kit antibody. c-Kit expression levels were detected by Western blotting. C, Ba/F3 cells were stably transfected with the Ba/F3-c-Kit and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F constructs. Cells were serum-starved overnight at 37 °C and stimulated by SCF for the indicated time periods. Cell lysates were prepared, immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Kit antibody, and analyzed by Western blotting. Total receptor phosphorylation was detected using phosphotyrosine (pY) antibody, and c-Kit was used as a loading control.

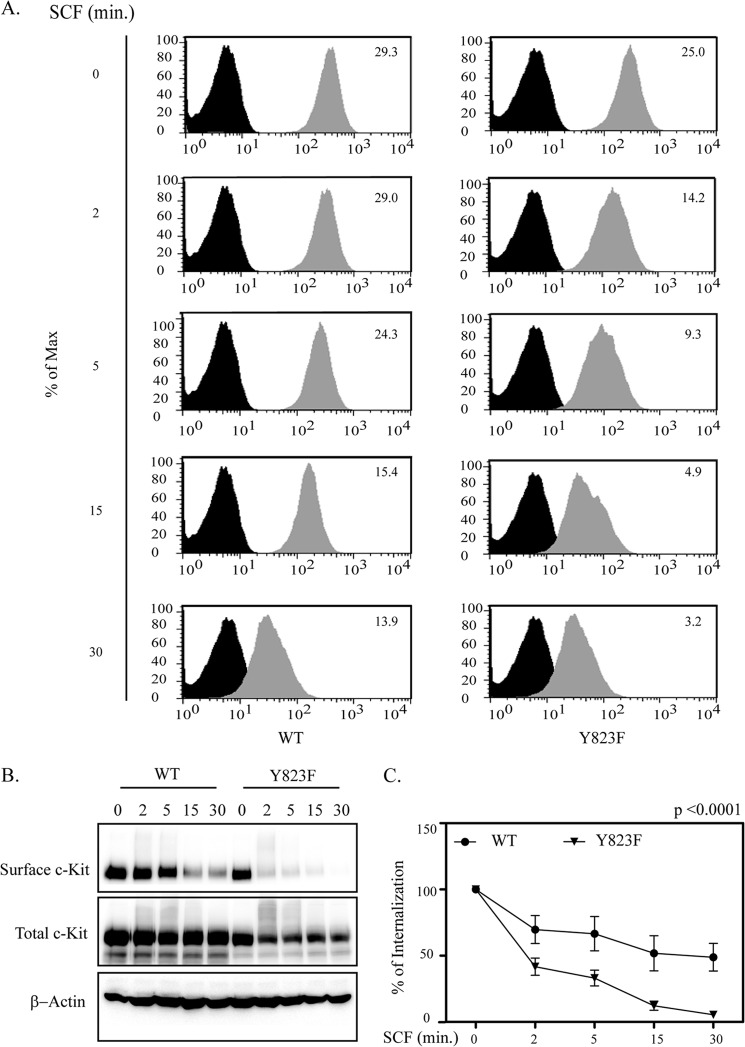

Ubiquitination and Degradation Are More Rapid in the Y823F Mutant Than in Wild-type c-Kit

It has been shown previously that receptor tyrosine kinases, upon ligand stimulation, undergo monoubiquitination or polyubiquitination that targets them to be internalized and degraded in the lysosomes or the proteasomes, respectively (1). Previous studies demonstrate that Cbl, which belongs to a family of ubiquitin E3 ligases, is crucial for ubiquitination of c-Kit (1, 7, 8). Furthermore, Cbl can either directly interact with c-Kit at Tyr-568 and Tyr-936 (1) or indirectly through the adapter protein Grb2 (8). This leads to monoubiquitination of c-Kit and targets it for degradation in lysosomes. We wanted to investigate whether mutation of Tyr-823 in the activation loop of c-Kit affects the phosphorylation of Cbl, which could result in changes in ubiquitination that, in turn, could affect receptor degradation. Cbl was immunoprecipitated from both wild-type and Y823F mutant c-Kit following ligand stimulation, and the extent of phosphorylation of Cbl was analyzed. The results demonstrate clearly that Cbl is phosphorylated already after 2 min. of SCF stimulation in both c-Kit WT and c-Kit-Y823F but that the mutant is unable to sustain the phosphorylation (Fig. 2A). To assess the degree of ubiquitination, c-Kit was immunoprecipitated, and Western blotting was performed using an antibody against ubiquitin. In agreement with the Cbl phosphorylation data, ubiquitination of c-Kit Y823F is very strong after 2 min of SCF stimulation but then declines rapidly. In contrast, ubiquitination of wild-type c-Kit is weaker but increases over a longer period of time (Fig. 2B). Degradation of c-Kit was analyzed by starving Ba/F3 cells in the presence of cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, for 4 h, followed by immunoprecipitation and detection using anti-c-Kit antibody. Degradation of the c-Kit receptor was analyzed for up to 30 min of SCF stimulation. We observed that in wild-type c-Kit-expressing cells, c-Kit is detectable for up to 30 min, whereas in cells expressing the Y823F mutant, c-Kit is degraded before 15 min of SCF stimulation (Fig. 2, C and D).

FIGURE 2.

The Y823F mutant of c-Kit mediates increased phosphorylation of Cbl concomitant with increased ubiquitination and degradation of c-Kit. A, Ba/F3-c-Kit and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F cells were serum-starved and stimulated with 100 ng/ml SCF for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-Cbl antibody, followed by Western blotting with phosphotyrosine antibodies and with a c-Kit antibody. B, lysates from serum-starved Ba/F3-c-Kit and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Kit antibody. Ubiquitination (Ub) of the receptor was detected using anti-Ub antibody. C, receptor degradation was assessed by serum starvation of Ba/F3-c-Kit and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F cells for 4 h at 37 °C in the presence of 100 μg/ml of cycloheximide. Cells were then stimulated with 100 ng/ml SCF for indicated periods of time, and cells were immediately placed on ice. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation with c-Kit antibodies, followed by immunodetection using c-Kit antibody. D, signal intensities from two independent experiments were quantified using Multi-Gauge software to calculate the percentage of receptor degradation.

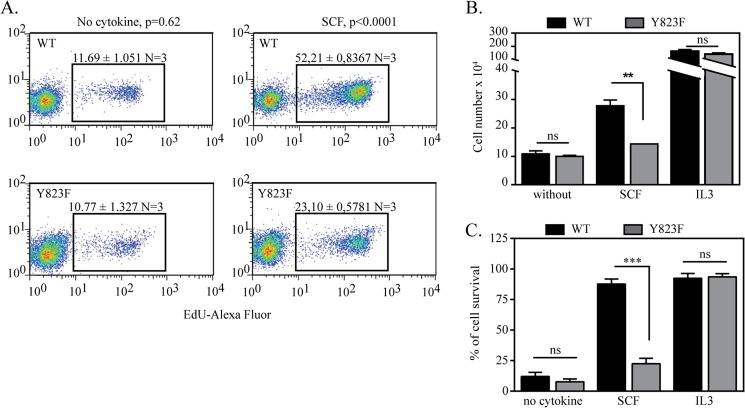

A change in Activation Loop Tyr-823 to Phenylalanine Causes the Receptor to Internalize Faster

It is known that, together with the JM domain, the activation loop also plays a role in maintaining the receptor in an inactivated state. Phosphorylation of Tyr-823 and of tyrosine residues in the JM domain is crucial to maintain the receptor in an active state. Moreover, previous reports show that Cbl, in addition to regulating the degradation of receptor tyrosine kinases, also regulates their internalization. Thus, we analyzed the pattern of receptor internalization in response to ligand activation. Ba/F3 cells were serum-starved in the presence of cycloheximide for 4 h and stimulated with SCF for the indicated periods of time. Cells were stained with a phycoerythrin-labeled anti-c-Kit antibody, and surface expression was determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A). As an alternative method, we verified the rate of internalization of cell surface c-Kit compared with the total c-Kit by Western blotting (Fig. 3, B and C). The data clearly demonstrate that the Y823F mutant of c-Kit is more rapidly internalized than wild-type c-Kit.

FIGURE 3.

The Y823F mutation of the activation loop of c-Kit enhances receptor internalization. Ba/F3-c-Kit and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F cells were serum-starved for 4 h at 37 °C in the presence of cycloheximide and stimulated with 100 ng/ml SCF for the indicated times. A, cells were transferred to ice followed by incubation with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-c-Kit antibody. The c-Kit surface expression level was analyzed by flow cytometry. Internalization of c-Kit was quantified at various time points compared with unstimulated cells. To determine mean fluorescence intensities of the wild-type receptor and the mutated receptor, FloJo software was used. B, cells were labeled with sulfo-NHS-biotin and incubated on ice for 40 min to allow biotinylation of cell surface proteins. Cells were lysed and processed for pull-down with immobilized avidin. The supernatant obtained after centrifugation was subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Kit antibody. c-Kit from both fractions was detected by Western blot analysis. C, internalization of c-Kit was quantified at various time points and analyzed statistically using GraphPad Prism. ***, p < 0.001.

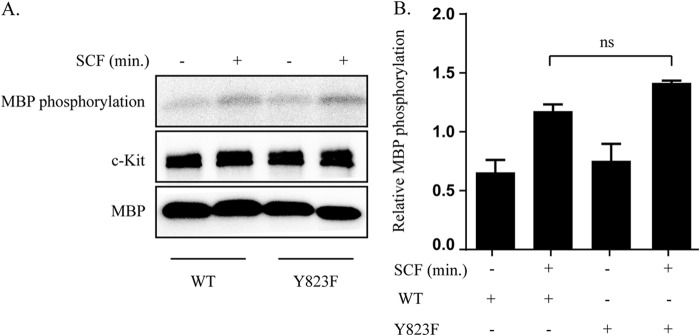

Mutation of Activation Loop Tyrosine 823 Has No Effect on Kinase Activity

Activation of c-Kit by its ligand triggers activation of numerous downstream signal transduction molecules. Some of these molecules are tyrosine kinases by themselves, e.g. Src family kinases such as Lyn and the Fes kinase (21, 22), and have been demonstrated to be able to phosphorylate c-Kit (23). Thus, the phosphorylation status of c-Kit in living cells could be influenced by factors other than the intrinsic kinase activity of c-Kit itself. Therefore, we wanted to evaluate the kinase activity of wild-type c-Kit and the Y823F c-Kit mutant in an in vitro assay. To test whether activation loop tyrosine has an effect on kinase activity, both wild-type and Y823F mutant c-Kit were transiently transfected into Cos1 cells and stimulated with SCF. Immunoprecipitates of c-Kit from these cells were incubated with myelin basic protein as an exogenous substrate, and an in vitro kinase reaction was performed. No change in kinase activity was observed between the wild-type and the Y823F mutated c-Kit receptor (Fig. 4, A and B), which is in agreement with previous reports (13).

FIGURE 4.

Y823F mutation in the activation loop does not affect receptor kinase activity. Cos1-c-Kit-WT and Cos1-c-Kit/Y823F cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 100 ng/ml SCF. Cell lysates were prepared, and c-Kit was immunoprecipitated. A, cell lysates were incubated with protein G beads, washed, and subjected to in vitro kinase assay with [γ32P]ATP and myelin basic protein (MBP) as an exogenous substrate. The phosphorylation signal was detected using L process software. c-Kit was detected by Western blotting. B, calculation of relative myelin basic protein phosphorylation and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism. ns, not significant.

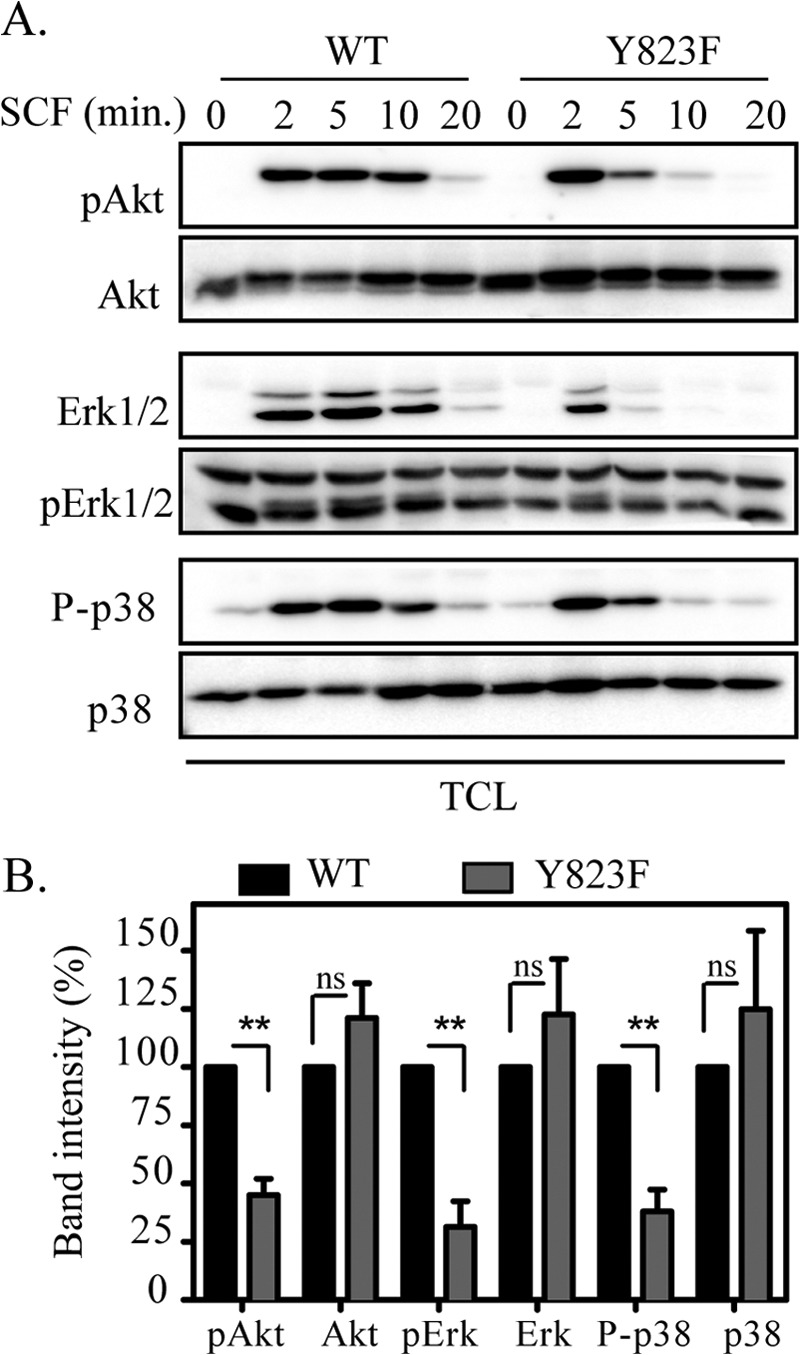

Mutation of Tyr-823 Negatively Affects the Akt and Erk Downstream Signaling Pathways

Activation of c-Kit upon ligand stimulation initiates sequential recruitment of several signaling molecules that form a network between the receptor and the cell nucleus. This networking is governed by several regulatory signal pathways, including the Ras/Erk, p38, and PI3K/Akt pathways (24). To investigate how mutation of Tyr-823 affects signal transduction, the phosphorylation of Akt, Erk, and p38 was examined by Western blotting using respective phosphospecific antibodies. Although Ba/F3 cells expressing wild-type c-Kit responded to SCF stimulation with phosphorylation of Akt that persisted for a longer time, activation of Ba/F3 cells expressing the Y823F mutant of c-Kit showed a strong but transient phosphorylation of Akt (Fig., 5, A and B). A similar trend was observed with Erk and p38 phosphorylation (Fig. 5, A and B).

FIGURE 5.

The Y823F mutation in c-Kit alters downstream signaling. Ba/F3-c-Kit WT and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F cells were serum-starved and treated with or without100 ng/ml SCF for the indicated periods of time. A, total cell lysates (TCL) were separated by SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred to an Immobilon P membrane, and probed with phospho-Akt (pAkt), phospho-Erk1/2 (pErk), and phosphor p38 (P-p38) antibodies. Antibodies against Akt, Erk, and p38 were used as loading controls. B, signal intensities from three independent experiments were quantified using Multi-Gauge software to calculate the reduction, and GraphPad Prism was used to calculate significance. ns, not significant. **, p < 0.01.

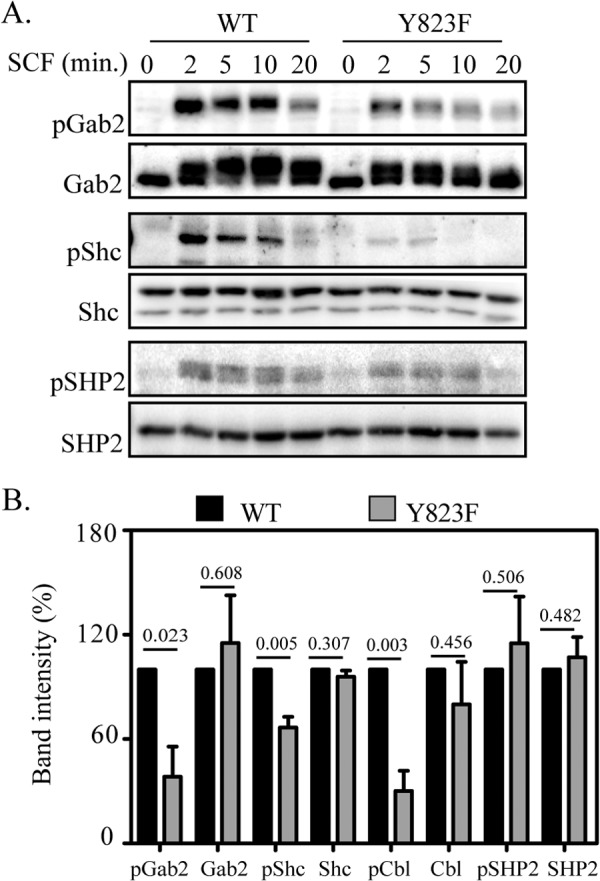

Effect of the Y823F Mutation on Phosphorylation of Adapter Proteins

Adaptor proteins such as Cbl, Shc, SHP2, and Gab2 are known to regulate the signal transduction through c-Kit either directly or through other adaptor proteins that, in turn, affect the downstream signaling pathways (24). We further analyzed the upstream adapter proteins that affect cell proliferation and cell survival. SCF stimulated Ba/F3 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation using specific antibodies, and phosphorylation of each adaptor protein was detected using phosphospecific antibodies. We observed that phosphorylation of Cbl, Shc, and Gab2 was reduced in cells expressing Y823F c-Kit compared with cells expressing wild-type c-Kit, whereas SHP2 phosphorylation was not affected significantly by Y823F mutation (Fig., 6, A and B).

FIGURE 6.

The phosphorylation mutant Y823F negatively regulates activation of adaptor proteins. A, Ba/F3-c-Kit-WT and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F cells were serum-starved and incubated in the presence or absence of SCF for the indicated periods of time. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies against Gab2, Shc, Cbl, and SHP2, respectively. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred to Immobilon P membranes and probed either with phosphospecific antibodies or general phosphotyrosine antibodies. B, Signal intensities from three independent experiments were quantified with Multi-Gauge software and statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prism. Values above each bar indicate the respective p values.

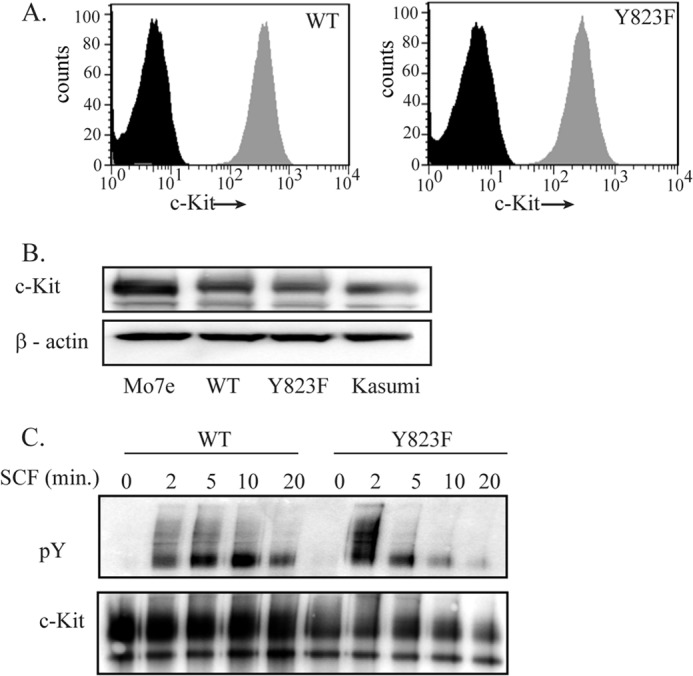

Mutation of Y823 Leads to a Significant Decrease in Both Cell Survival and Proliferation

We wanted to ascertain whether the mutation of activation loop tyrosine in c-Kit had an effect on the survival and proliferation of cells. The cells lacking Tyr-823 showed a significant reduction in proliferation, as confirmed by 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation in proliferating cells and trypan blue exclusion method (Fig. 7, A and B). The effect of the Y823F mutation of c-Kit on cell survival was also examined by staining the cells with annexin V and 7-amino actinomycin D and analysis by flow cytometry. Ba/F3 cell expressing the Y823F mutant of c-Kit showed almost a 60% reduction in cell survival compared with cells expressing wild-type c-Kit (Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Cells expressing the Y823F mutant of c-Kit display reduced cell proliferation and cell survival in response to SCF stimulation. Ba/F3-c-Kit WT and Ba/F3-c-Kit/Y823F cells were grown for 48 h in the presence or absence of SCF and IL-3. A, cells were incubated with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) for 2 h, fixed, labeled with Alexa Fluor 647, and analyzed by flow cytometry. B, viable cells were counted by trypan blue exclusion method. C, cells were labeled with annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D, and living cells were measured by flow cytometry. IL-3 was used as a positive control. Quantification of labeled cells was obtained with FloJo software, and results from three independent experiments were analyzed statistically using GraphPad Prism. ns, not significant. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The activation loop of c-Kit spans about 20–25 amino acids in the C-lobe of the kinase domain and, together with the juxtamembrane domain, maintains the kinase in an autoinhibitory state. Studies indicate that two key processes are required for activation of kinase, one is the release of the JM domain that exposes the catalytic site to the substrate, and the second is the activation loop coming to the DFG-in state. We have observed that c-Kit phosphorylation is not hampered by the Y823F mutation. Tyr-823 is the only tyrosine phosphorylation site in the activation loop, and yet the previous structural studies point to its irrelevance in the kinase activation process. So what is Tyr-823 doing in the activation loop? Does it have any role in downstream signaling through the c-Kit receptor?

Except for being involved in regulation of kinase activity, little is known about the role of activation loop tyrosines in other receptor tyrosine kinases. In non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Syk phosphorylation of activation loop tyrosines is described as being crucial for the propagation of signaling through the immunoreceptor but does not affect the kinase activity of Syk (25). In an early report from Serve et al. (26), Tyr-821 in murine c-Kit (homologous to Tyr-823 in human c-Kit) was shown to be of importance for proliferation and survival in murine bone marrow-derived mast cells without affecting PI3-kinase, p21ras, or Erk activation. However, the discrepancy with our data on Erk activation could be explained by the use of different cell systems. The EGF receptor Tyr-845, analogous to Tyr-823 in c-Kit, was demonstrated to be required in mitogenic pathways and as a mediator for an association between CoxII and the EGF receptor crucial for cell survival (27, 28). In both c-Kit Tyr-821 and EGF receptor Tyr-845, a phenylalanine mutant showed reduced cell survival. In the PDGF receptor, activation loop Tyr-857 was shown to be crucial for in vitro kinase activity and for cell proliferation but did not affect internalization (29). In this study, we show that Y823F affects downstream signaling pathways of c-Kit, that it is fully dispensable for kinase activity, and that the mutated receptor is internalized and degraded at a much accelerated rate compared with the wild-type receptor. Mutation of Tyr-823 to Y823F further significantly reduced cell proliferation and survival. Thus, this study adds new perspectives to the existing knowledge about the role of activation loop tyrosine (Tyr-823) in c-Kit signaling.

Previous studies on the kinetics of phosphorylation of c-Kit have provided valuable information on the role of Tyr-823 in c-Kit activation (13). However, those studies were performed on a recombinant intracellular fragment of c-Kit, and, thus, was lacking the ligand-binding domain. Furthermore, in a cell-free system, the other tyrosine kinases and molecules that affect c-Kit signaling (such as Src and Fes) are lacking, and their contribution to phosphorylation of the receptor is not seen. Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation experiments on ligand-induced c-Kit activation demonstrate that the Y823F mutant of c-Kit is able to transduce a phosphorylation signal but at a much accelerated rate and is considerably more transient in its nature compared with wild-type c-Kit. Cbl, a ubiquitin E3 ligase is known to regulate ubiquitination and degradation of receptor tyrosine kinases. We observed that phosphorylation of Cbl increases when we increase the ligand stimulation time in the wild type receptor, whereas it decreases in Y823F. The effect on short-lived ubiquitination and faster degradation could also be due to instant dephosphorylation after a brief phosphorylation of Cbl. The mutant receptor is also internalized much faster than the wild-type receptor. This could again be explained by the phosphorylation status of Cbl, which is known to regulate internalization (1). Thus, the effects on ubiquitination, internalization, and degradation could be the consequence of Cbl inactivation, which can interact with c-Kit either directly or through activation of Src kinases. Further, phosphorylation of adaptor proteins such as Gab2 and Shc is also reduced in Y823F as compared with the wild-type receptor. These molecules are downstream of Src family kinases, which directly interact with c-Kit (30, 31). Gab2 and Shc are connected to the Akt and Erk pathways downstream (21, 24). Therefore, a reduction in Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation could be explained by altered Shc and Gab2 signaling molecules. Reduced Akt and Erk1/2 phosphorylation reduce cell survival and cell proliferation, which are linked to the Akt and Erk pathways. Similar observations have been made in the PDGFβ receptor, where the activation loop Y857F mutation hampers complete activation of Akt and Erk (29). On the contrary, Y857F also led to reduced SHP2 activation, which was not the case with Y823F in c-Kit. A reduction in SHP2 phosphorylation has been proposed to lead to reduction in Erk phosphorylation. Since SHP2 is not affected in our case, there is likely to be an alternate pathway affecting Erk signaling (29, 32). One likely candidate for this is the adapter protein Shc because we have shown previously that Src-phosphorylation of Shc is essential for the ability of c-Kit to mediate activation of Erk (21). Similarly, transient phosphorylation of p38 could also be caused by a reduction in Src-mediated Shc phosphorylation (33, 34). Its role in cell migration has also been described previously (35). Thus, mutation in activation loop tyrosine Tyr-823 affects multiple signaling pathways, as also described for Syk kinase, where activation loop tyrosines are crucial for sustained downstream signaling without being involved in catalysis (36, 37). On the basis of previous studies and our own data, a perspective toward function of activation loop tyrosine is that when the c-Kit receptor dimerizes and autophosphorylates, the potential tyrosine residues on the JM domain are phosphorylated and release the autoinhibitory state. Next is the phosphorylation of activation loop tyrosine that, upon phosphorylation, makes the loop in the DFG-in state and locks the kinase from an inactivated state into an activated state. However, when Tyr-823 is mutated to Phe-823, there is a conformational change and a destabilization of the kinase so that the activated state is no longer maintained. It could be due to this reason that signaling through the mutated receptor initiates normally but is not sustained because of a destabilized receptor, which leads to a faster internalization, degradation, and a marked reduction in cell viability and cell proliferation capacity. However, a change in conformation is suspected, but it excludes the domain binding to kinase inhibitor sunitinib. As proposed by DiNitto et al. (13), the Y823F mutation could render the enzyme more flexible so that, after activation, it comes back to the DFG-out inactivated state preferred by most kinase inhibitors.

It turns out that the effect of mutating Tyr-823 is very much dependent on which amino acid replaces the tyrosine at position 823. DiNitto et al. (13) demonstrated in their in vitro cell-free system that Y823A and Y823D were devoid of kinase activity, while the Y823F mutant has full activity. It is interesting that the Y823D mutation of c-Kit has been described in human testicular seminomas (38), malignant melanomas (39), gastrointestinal stromal tumors (40), and pediatric core factor-binding acute myeloid leukemia (41). The Y823D mutant was found to be constitutively active in living cells (38). This apparent discrepancy in results might be attributable to the fact that, in the living cell, c-Kit has access to accessory molecules that are missing in a cell-free system and that are necessary for its signaling. Furthermore, the Y823C (38) and Y823N (42) mutants have also been identified in tumors, but no data are available as to whether these mutations are also activating. Thus, the signaling outcome is determined by which amino acid replaces the tyrosine residue. In one case (Y823A), the receptor will lack kinase activity; in another (Y823F), the kinase activity is unaffected; and in a third (Y823D), the kinase is constitutively active.

In view of our results, Tyr-823 appears to be a good target for cancer therapy. Y823F makes the receptor not only more sensitive to therapeutic targets such as sunitinib and imatinib but also destabilizes the receptor so that activation of Akt, Erk1/2, and p38 is reduced. This, in turn, leads to a significant reduction in cell proliferation and cell survival. Thus, a therapy targeting Tyr-823 so that its phosphorylation is prevented could, in combination with chemotherapy, provide an improved treatment option for tumors caused by c-Kit mutations. This study exemplifies that even when the sequence of kinase domains is highly conserved across members of the receptor tyrosine kinase family, point mutations of various receptors play divergent roles in cellular outcomes and in the mechanism of signal transduction. This underlines the importance of investigating further point mutations in c-Kit and the mechanisms by which they influence cell signaling to improve our current understanding of the association of receptor mutations with cancer prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susanne Bengtsson for technical assistance and Jianmin Sun, Elena Razumovskaya, and Vaibhav Agarwal for help with the use of software.

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, and the Gunnar Nilssons Cancer Foundation.

- SCF

- stem cell factor

- JM

- juxtamembrane.

REFERENCES

- 1. Masson K., Heiss E., Band H., Rönnstrand L. (2006) Direct binding of Cbl to Tyr-568 and Tyr-936 of the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit is required for ligand-induced ubiquitination, internalization and degradation. Biochem. J. 399, 59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lennartsson J., Rönnstrand L. (2012) Stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit. From basic science to clinical implications. Physiol. Rev. 92, 1619–1649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hirota S., Isozaki K., Moriyama Y., Hashimoto K., Nishida T., Ishiguro S., Kawano K., Hanada M., Kurata A., Takeda M., Muhammad Tunio G., Matsuzawa Y., Kanakura Y., Shinomura Y., Kitamura Y. (1998) Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 279, 577–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishida T., Hirota S., Taniguchi M., Hashimoto K., Isozaki K., Nakamura H., Kanakura Y., Tanaka T., Takabayashi A., Matsuda H., Kitamura Y. (1998) Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumours with germline mutation of the KIT gene. Nat. Genet. 19, 323–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kitamura Y., Hirota S., Nishida T. (2001) A loss-of-function mutation of c-kit results in depletion of mast cells and interstitial cells of Cajal, while its gain-of-function mutation results in their oncogenesis. Mutat. Res. 477, 165–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lennartsson J., Jelacic T., Linnekin D., Shivakrupa R. (2005) Normal and oncogenic forms of the receptor tyrosine kinase kit. Stem Cells 23, 16–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zeng S., Xu Z., Lipkowitz S., Longley J. B. (2005) Regulation of stem cell factor receptor signaling by Cbl family proteins (Cbl-b/c-Cbl). Blood 105, 226–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun J., Pedersen M., Bengtsson S., Rönnstrand L. (2007) Grb2 mediates negative regulation of stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit signaling by recruitment of Cbl. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 3935–3942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furdui C. M., Lew E. D., Schlessinger J., Anderson K. S. (2006) Autophosphorylation of FGFR1 kinase is mediated by a sequential and precisely ordered reaction. Mol. Cell 21, 711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hubbard S. R. (1997) Crystal structure of the activated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase in complex with peptide substrate and ATP analog. EMBO J. 16, 5572–5581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mol C. D., Dougan D. R., Schneider T. R., Skene R. J., Kraus M. L., Scheibe D. N., Snell G. P., Zou H., Sang B. C., Wilson K. P. (2004) Structural basis for the autoinhibition and STI-571 inhibition of c-Kit tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 31655–31663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mol C. D., Lim K. B., Sridhar V., Zou H., Chien E. Y., Sang B. C., Nowakowski J., Kassel D. B., Cronin C. N., McRee D. E. (2003) Structure of a c-kit product complex reveals the basis for kinase transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31461–31464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DiNitto J. P., Deshmukh G. D., Zhang Y., Jacques S. L., Coli R., Worrall J. W., Diehl W., English J. M., Wu J. C. (2010) Function of activation loop tyrosine phosphorylation in the mechanism of c-Kit auto-activation and its implication in sunitinib resistance. J. Biochem. 147, 601–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blume-Jensen P., Siegbahn A., Stabel S., Heldin C. H., Rönnstrand L. (1993) Increased Kit/SCF receptor induced mitogenicity but abolished cell motility after inhibition of protein kinase C. EMBO J. 12, 4199–4209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lupher M. L., Jr., Reedquist K. A., Miyake S., Langdon W. Y., Band H. (1996) A novel phosphotyrosine-binding domain in the N-terminal transforming region of Cbl interacts directly and selectively with ZAP-70 in T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 24063–24068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun J., Pedersen M., Rönnstrand L. (2008) Gab2 is involved in differential phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling by two splice forms of c-Kit. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27444–27451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun J., Pedersen M., Rönnstrand L. (2009) The D816V mutation of c-Kit circumvents a requirement for Src family kinases in c-Kit signal transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11039–11047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hansen K., Johnell M., Siegbahn A., Rorsman C., Engström U., Wernstedt C., Heldin C. H., Rönnstrand L. (1996) Mutation of a Src phosphorylation site in the PDGF β-receptor leads to increased PDGF-stimulated chemotaxis but decreased mitogenesis. EMBO J. 15, 5299–5313 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kamps M. P., Sefton B. M. (1989) Acid and base hydrolysis of phosphoproteins bound to immobilon facilitates analysis of phosphoamino acids in gel-fractionated proteins. Anal. Biochem. 176, 22–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kazi J. U., Sun J., Rönnstrand L. (2013) The presence or absence of IL-3 during long-term culture of Flt3-ITD and c-Kit-D816V expressing Ba/F3 cells influences signaling outcome. Exp. Hematol. 41, 585–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lennartsson J., Blume-Jensen P., Hermanson M., Pontén E., Carlberg M., Rönnstrand L. (1999) Phosphorylation of Shc by Src family kinases is necessary for stem cell factor receptor/c-kit mediated activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and c-fos induction. Oncogene 18, 5546–5553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smith J. A., Samayawardhena L. A., Craig A. W. (2010) Fps/Fes protein-tyrosine kinase regulates mast cell adhesion and migration downstream of Kit and β1 integrin receptors. Cell. Signal. 22, 427–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lennartsson J., Wernstedt C., Engström U., Hellman U., Rönnstrand L. (2003) Identification of Tyr-900 in the kinase domain of c-Kit as a Src-dependent phosphorylation site mediating interaction with c-Crk. Exp. Cell Res. 288, 110–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Masson K., Rönnstrand L. (2009) Oncogenic signaling from the hematopoietic growth factor receptors c-Kit and Flt3. Cell. Signal. 21, 1717–1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang J., Billingsley M. L., Kincaid R. L., Siraganian R. P. (2000) Phosphorylation of Syk activation loop tyrosines is essential for Syk function. An in vivo study using a specific anti-Syk activation loop phosphotyrosine antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35442–35447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Serve H., Yee N. S., Stella G., Sepp-Lorenzino L., Tan J. C., Besmer P. (1995) Differential roles of PI3-kinase and Kit tyrosine 821 in Kit receptor-mediated proliferation, survival and cell adhesion in mast cells. EMBO J. 14, 473–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boerner J. L., Demory M. L., Silva C., Parsons S. J. (2004) Phosphorylation of Y845 on the epidermal growth factor receptor mediates binding to the mitochondrial protein cytochrome c oxidase subunit II. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 7059–7071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boerner J. L., Biscardi J. S., Silva C. M., Parsons S. J. (2005) Transactivating agonists of the EGF receptor require Tyr 845 phosphorylation for induction of DNA synthesis. Mol. Carcinog. 44, 262–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wardega P., Heldin C. H., Lennartsson J. (2010) Mutation of tyrosine residue 857 in the PDGF β-receptor affects cell proliferation but not migration. Cell Signal 22, 1363–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Daub H., Weiss F. U., Wallasch C., Ullrich A. (1996) Role of transactivation of the EGF receptor in signalling by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 379, 557–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luttrell L. M., Daaka Y., Della Rocca G. J., Lefkowitz R. J. (1997) G protein-coupled receptors mediate two functionally distinct pathways of tyrosine phosphorylation in rat 1a fibroblasts. Shc phosphorylation and receptor endocytosis correlate with activation of Erk kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31648–31656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rönnstrand L., Arvidsson A. K., Kallin A., Rorsman C., Hellman U., Engström U., Wernstedt C., Heldin C. H. (1999) SHP-2 binds to Tyr-763 and Tyr-1009 in the PDGF β-receptor and mediates PDGF-induced activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and chemotaxis. Oncogene 18, 3696–3702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ueda S., Mizuki M., Ikeda H., Tsujimura T., Matsumura I., Nakano K., Daino H., Honda Zi Z., Sonoyama J., Shibayama H., Sugahara H., Machii T., Kanakura Y. (2002) Critical roles of c-Kit tyrosine residues 567 and 719 in stem cell factor-induced chemotaxis. Contribution of src family kinase and PI3-kinase on calcium mobilization and cell migration. Blood 99, 3342–3349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Samayawardhena L. A., Hu J., Stein P. L., Craig A. W. (2006) Fyn kinase acts upstream of Shp2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase to promote chemotaxis of mast cells towards stem cell factor. Cell. Signal. 18, 1447–1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sundström M., Alfredsson J., Olsson N., Nilsson G. (2001) Stem cell factor-induced migration of mast cells requires p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Exp. Cell Res. 267, 144–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carsetti L., Laurenti L., Gobessi S., Longo P. G., Leone G., Efremov D. G. (2009) Phosphorylation of the activation loop tyrosines is required for sustained Syk signaling and growth factor-independent B-cell proliferation. Cell Signal 21, 1187–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kulathu Y., Grothe G., Reth M. (2009) Autoinhibition and adapter function of Syk. Immunol. Rev. 232, 286–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kemmer K., Corless C. L., Fletcher J. A., McGreevey L., Haley A., Griffith D., Cummings O. W., Wait C., Town A., Heinrich M. C. (2004) KIT mutations are common in testicular seminomas. Am. J. Pathol. 164, 305–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beadling C., Jacobson-Dunlop E., Hodi F. S., Le C., Warrick A., Patterson J., Town A., Harlow A., Cruz F., 3rd, Azar S., Rubin B. P., Muller S., West R., Heinrich M. C., Corless C. L. (2008) KIT gene mutations and copy number in melanoma subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 6821–6828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Calabuig-Fariñas S., López-Guerrero J. A., Navarro S., Machado I., Poveda A., Pellín A., Llombart-Bosch A. (2011) Evaluation of prognostic factors and their capacity to predict biological behavior in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 19, 448–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Goemans B. F., Zwaan C. M., Miller M., Zimmermann M., Harlow A., Meshinchi S., Loonen A. H., Hählen K., Reinhardt D., Creutzig U., Kaspers G. J., Heinrich M. C. (2005) Mutations in KIT and RAS are frequent events in pediatric core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 19, 1536–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Willmore-Payne C., Holden J. A., Chadwick B. E., Layfield L. J. (2006) Detection of c-kit exons 11- and 17-activating mutations in testicular seminomas by high-resolution melting amplicon analysis. Mod. Pathol. 19, 1164–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]